Vol. II.

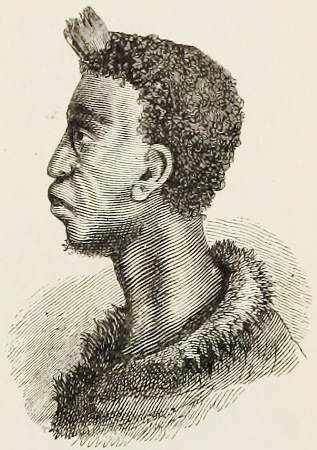

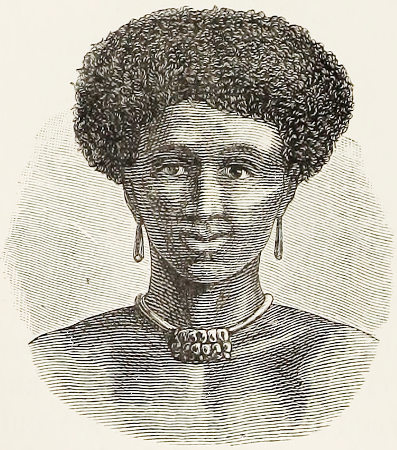

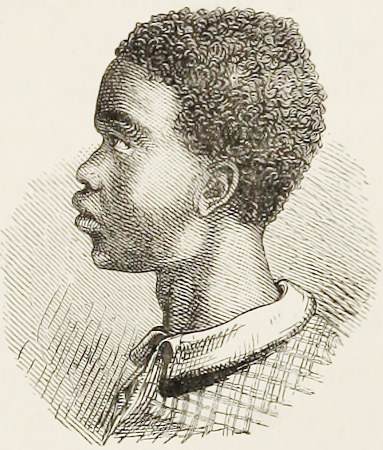

Frontispiece.

Vol. II.

Frontispiece.

TRAVELS, RESEARCHES, AND HUNTING ADVENTURES,

BETWEEN THE DIAMOND-FIELDS AND THE ZAMBESI (1872–79).

BY

Dr. EMIL HOLUB.

TRANSLATED BY ELLEN E. FREWER.

WITH ABOUT TWO HUNDRED ORIGINAL ILLUSTRATIONS AND A MAP.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. II.

London:

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON, SEARLE, & RIVINGTON,

CROWN BUILDINGS, 188, FLEET STREET.

1881.

[All rights reserved.]

LONDON:

GILBERT AND RIVINGTON, PRINTERS,

ST. JOHN’S SQUARE.

| CHAPTER I. | |

|---|---|

| From the Diamond Fields to the Molapo. | |

| PAGE | |

| Departure from Dutoitspan—Crossing the Vaal—Graves in the Harts River valley—Mamusa—Wild-goose shooting on Moffat’s Salt Lake—A royal crane’s nest—Molema’s Town—Barolong weddings—A lawsuit—Cold weather—The Malmani valley—Weltufrede farm | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| From Jacobsdal to Shoshong. | |

| Zeerust—Arrival at Linokana—Harvest-produce—The lion-ford on the Marico—Silurus-fishing—Crocodiles in the Limpopo—Damara-emigrants—A narrow escape—The Banks of the Notuany—The Puff-adder valley | 21 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| From Shoshong to the Great Salt Lakes. | |

| Khame and Sekhomo—Signs of erosion in the bed of the Luala—The Maque plains—Frost—Wild ostriches—Eland-antelopes—The first palms—Assegai traps—The district of the Great Salt Lakes—The Tsitane and Karri-Karri salt-pans—The Shaneng—The Soa salt-pan—Troublesome visitors—Salt in the Nataspruit—Chase of a Zulu hartebeest—Animal life on the Nataspruit—Waiting for a lion | 42 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| From the Nataspruit to Tamasetze. | |

| Saltbeds in the Nataspruit—Poisoning jackals—A good shot—An alarm—The sandy pool-plateau—Ostriches—Travelling by torchlight—Meeting with elephant-hunters—The Madenassanas—Madenassana manners and customs—The Yoruah pool and the Tamafopa springs—Animal-life in the forest by night—Pit’s slumbers—An unsuccessful lion’s-hunt—Watch for elephants—Tamasetze | 70 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| From Tamasetze to the Chobe. | |

| Henry’s Pan—Hardships of elephant-hunting—Elephants’ holes—Arrival in the Panda ma Tenka valley—Mr. Westbeech’s depôt—South African lions—Their mode of attack—Blockley—Schneeman’s Pan—Wild honey—The Leshumo valley—Trees damaged by elephants—On the bank of the Chobe | 95 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| In the Valleys of the Chobe and the Zambesi. | |

| Vegetation in the valley of the Chobe—Notification of my arrival—Scenery by the rapids—A party of Masupias—My mulekow—Matabele raids upon Sekeletu’s territory—Gourd-shells—Masupia graves—Animal life on the Chobe—Masupia huts—Englishmen in Impalera—Makumba—My first boat-journey on the Zambesi—Animal life in the reed-thickets—Blockley’s kraal—Hippopotamuses—Old Sesheke | 110 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| First Visit to the Marutse Kingdom. | |

| My reception by Sepopo—The libeko—Sepopo’s pilfering propensities—The royal residence—History of the Marutse-Mabunda empire—The various tribes and their districts—Position of the vassal tribes—The Sesuto language—Discovery of a culprit—Portuguese traders at Sepopo’s court—Arrangements for exploring the country—Construction of New Sesheke—Fire in Old Sesheke—Culture of the tribes of the Marutse-Mabunda kingdom—Their superstition—Rule of succession—Resources of the sovereign—Style of building—The royal courtyard—Musical instruments—War-drums—The kishi dance—Return to Impalera and Panda ma Tenka—A lion adventure | 136 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Trip to the Victoria Falls. | |

| Return to Panda ma Tenka—Theunissen’s desertion—Departure for the falls—Orbeki-gazelles—Animal and vegetable life in the fresh-water pools—Difficult travelling—First sight of the falls—Our skerms—Characteristics of the falls—Their size and splendour—Islands in the river-bed—Columns of vapour—Roar of the water—The Zambesi below the falls—The formation of the rocks—Rencontre with baboons—A lion-hunt—The Manansas—Their history and character—Their manners and customs—Disposal of the dead—Ornaments and costume—The Albert country—Back again | 180 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Second Visit to the Marutse Kingdom. | |

| Departure for Impalera—A Masupia funeral—Sepopo’s wives—Travelling plans—Flora and fauna of the Sesheke woods—Arrival of a caravan—A fishing excursion—Mashoku, the king’s executioner—Massangu—The prophetic dance—Visit from the queens—Blacksmith’s bellows—Crocodiles and crocodile-tackle—The Mankoë—Constitution and officials of the Marutse kingdom—A royal elephant-hunt—Excursion to the woods—A buffalo-hunt—Chasing a lioness—The lion dance—Mashukulumbe at Sepopo’s court—Moquai, the king’s daughter—Marriage festivities | 214 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Up the Zambesi. | |

| Departure from Sesheke—The queens’ squadron—First night’s camp—Symptoms of fever—Agricultural advantages of the Zambesi valley—Rapids and cataracts of the Central Zambesi—The Mutshila-Aumsinga rapids—A catastrophe—Encampment near Sioma—A conspiracy—Lions around Sioma—My increasing illness | 266 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Back again in Sesheke. | |

| Visits of condolence—Unpopularity of Sepopo—Mosquitoes—Goose hunting—Court ceremonial at meals—Modes of fishing—Sepopo’s illness—Vassal tribes of the Marutse empire—Characteristics of the Marutse tribes—The future of the country | 283 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Manners and Customs of the Marutse Tribes. | |

| Ideas of religion—Mode of living—Husbandry and crops—Consumption and preparation of food—Cleanliness—Costume—Position of the women—Education of children—Marriages—Disposal of the dead—Forms of greeting—Modes of travelling—Administration of justice—An execution—Knowledge of medicine—Superstition—Charms—Human Sacrifices—Clay and wooden vessels—Calabashes—Basket-work—Weapons—Manufacture of clothing—Tools—Oars—Pipes and snuff-boxes—Ornaments—Toys, tools, and fly-flappers | 300 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| In the Leshumo Valley. | |

| Departure from Shesheke—Refractory boatmen—An effectual remedy—Beetles in the Leshumo Valley—The chief Moia—A phenomenon—A party of invalids—Sepopo’s bailiffs—Kapella’s flight—A heavy storm—Discontent in the Marutse kingdom—Departure for Panda ma Tenka | 354 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Through the Makalaka and West Matabele Countries. | |

| Start southwards—Vlakvarks—An adventurer—The Tamasanka pools—The Libanani glade—Animal life on the plateau—The Maytengue—An uneasy conscience—Menon the Makalaka chief—A spy—Menon’s administration of justice—Pilfering propensities and dirtiness of the Makalakas—Morula trees—A Matabele warrior—An angry encounter—Ruins on the Rocky Shasha—Scenery on the Rhamakoban river—A deserted gold-ield—History of the Matabele kingdom—More ruins—Lions on the Tati—Westbeech and Lo Bengula—The leopard in Pit Jacobs’ house—Journey continued | 372 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| From Shoshong to the Diamond Fields. | |

| Arrival at Shoshong—Z.’s chastisement—News from the colony—Departure from Shoshong—Conflict between the Bakhatlas and Bakuenas—Mochuri—A pair of young lions—A visit from Eberwald—Medical practice in Linokana—Joubert’s Lake—A series of salt-pans—Arrival in Kimberley | 418 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Last Visit to the Diamond Fields. | |

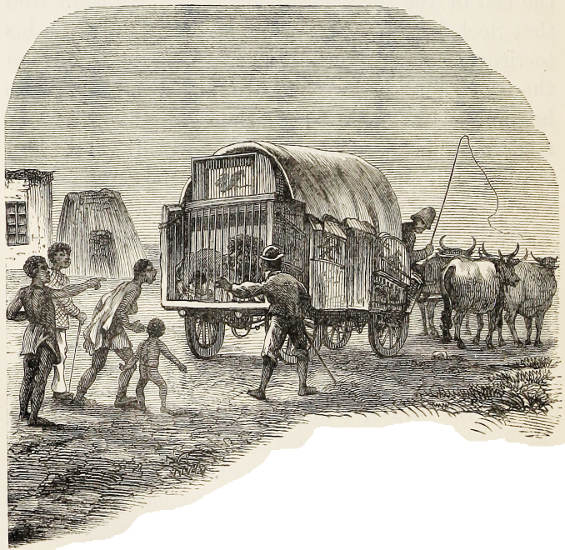

| Resuming medical practice—My menagerie at Bultfontein—Exhibition at Kimberley—Visit to Wessel’s Farm— Bushmen’s carvings—Hunting hyænas and earth-pigs—The native question in South Africa—War in Cape Colony and Griqualand West—Major Lanyon and Colonel Warren—Departure for the coast | 432 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Through the Colony to the Coast. | |

| Departure from Bultfontein—Philippolis—Ostrich-breeding—My first lecture—Fossils—A perilous crossing—The Zulu war—Mode of dealing with natives—Grahamstown—Arrival at Port Elizabeth—My baggage in danger—Last days in Cape Town—Summary of my collections—Return to Europe | 454 |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

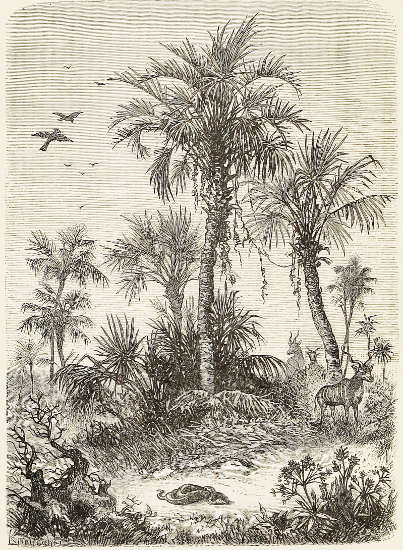

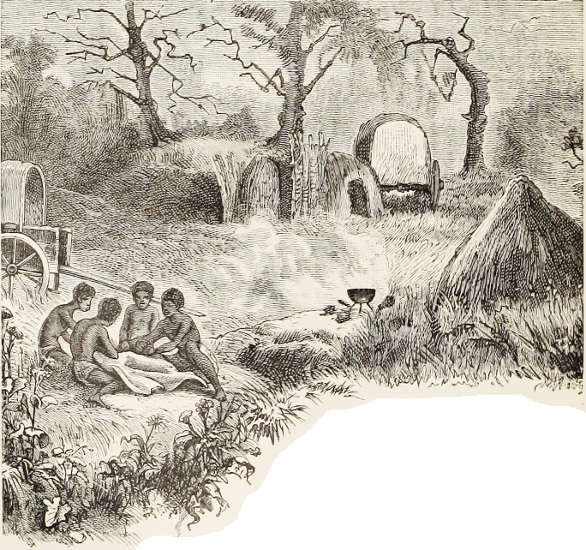

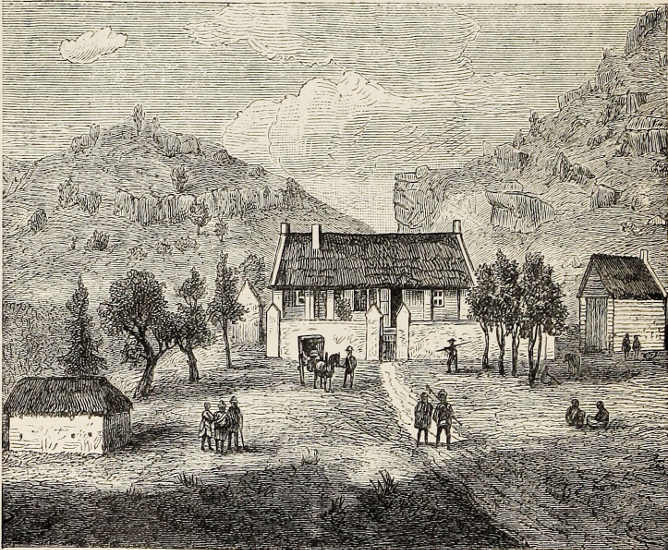

| Frontispiece. | |

| Pond near Coetze’s Farm | 4 |

| Graves under the Camel-thorn Trees at Mamusa | 6 |

| Shooting Wild Geese at Moffat’s Salt Pan | 9 |

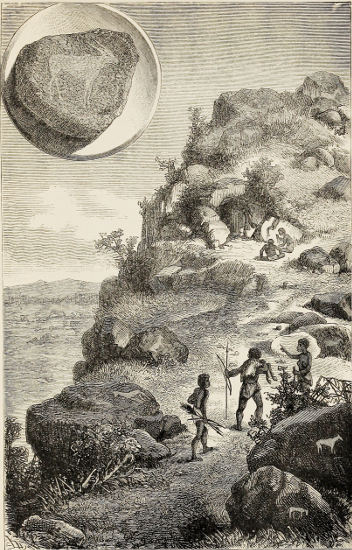

| Hunting among the Rocks at Molema | 11 |

| Baboon Rocks | 14 |

| On the Banks of the Matebe Rivulet | 24 |

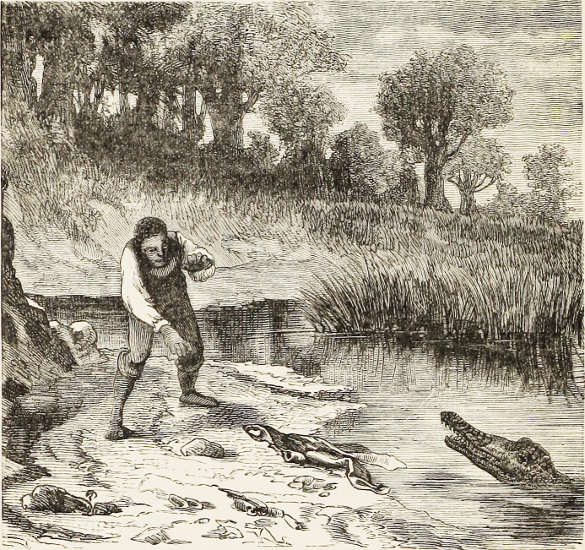

| Crocodile in the Limpopo | 32 |

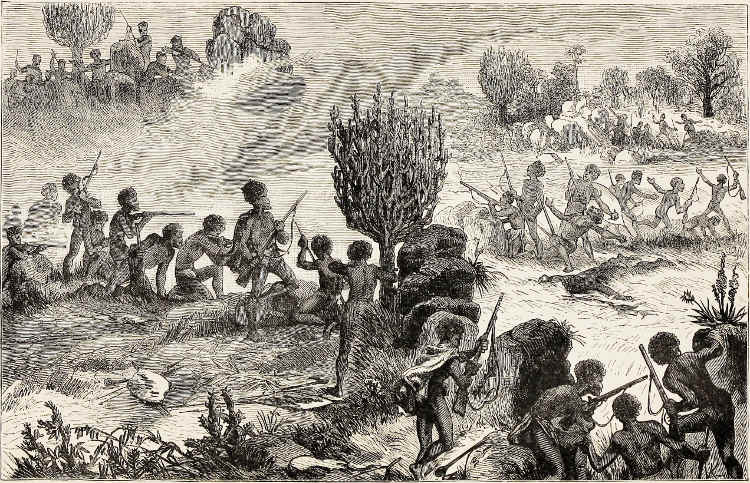

| Battle on the Heights of Bamangwato | 43 |

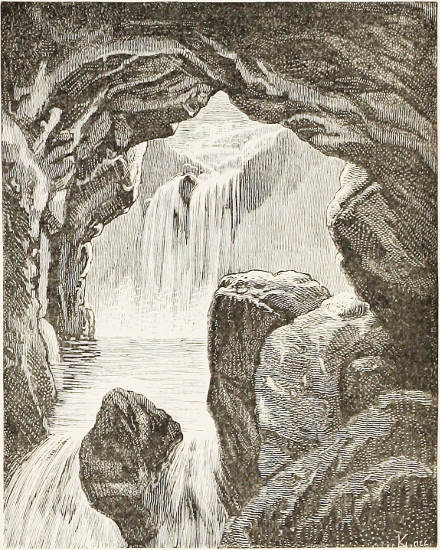

| Grottoes of the Luala | 46 |

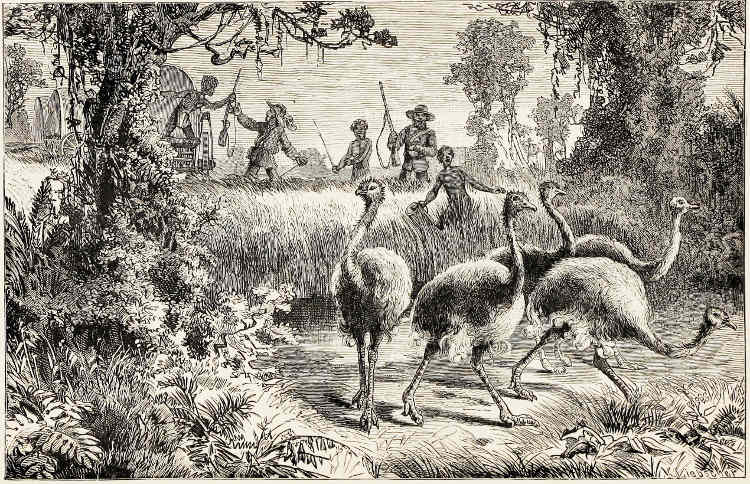

| Troop of Ostriches | 49 |

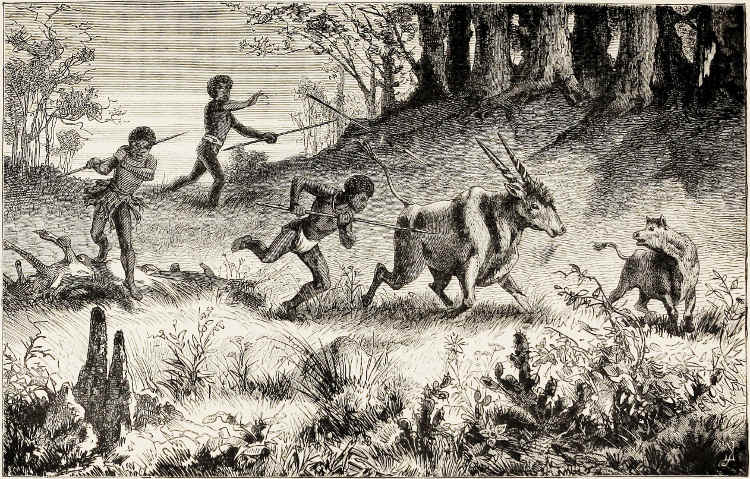

| Masarwas chasing the Eland | 50 |

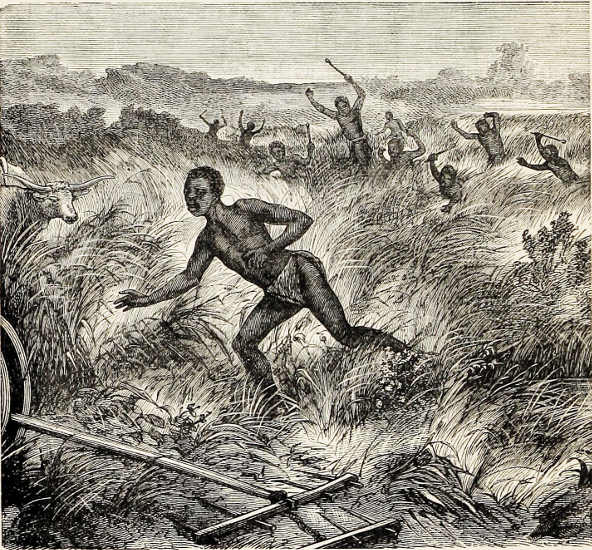

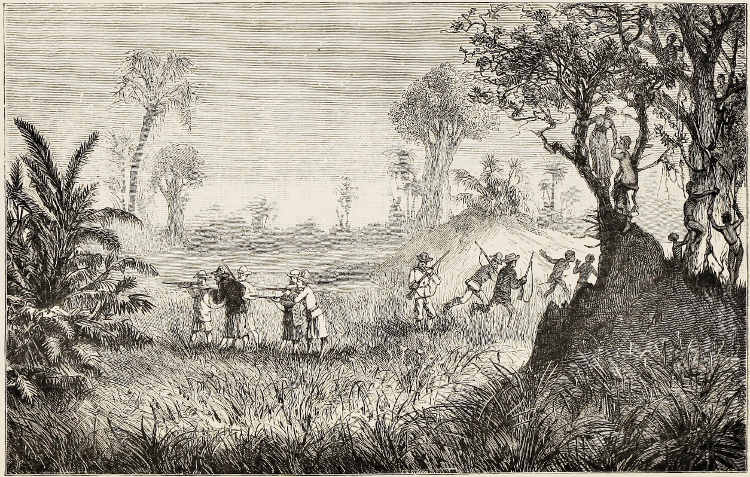

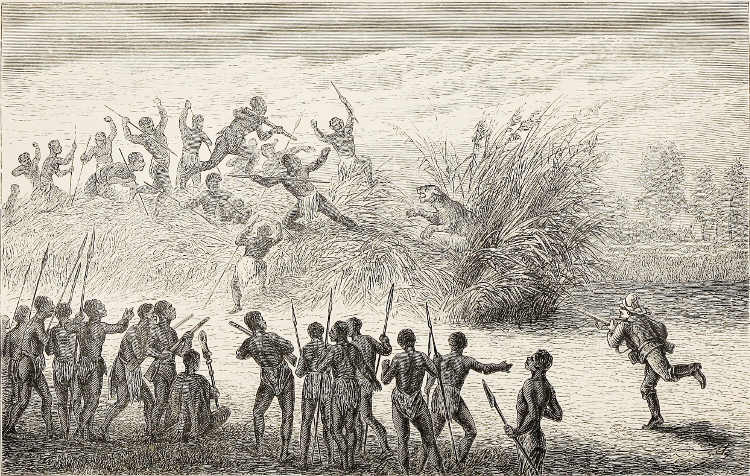

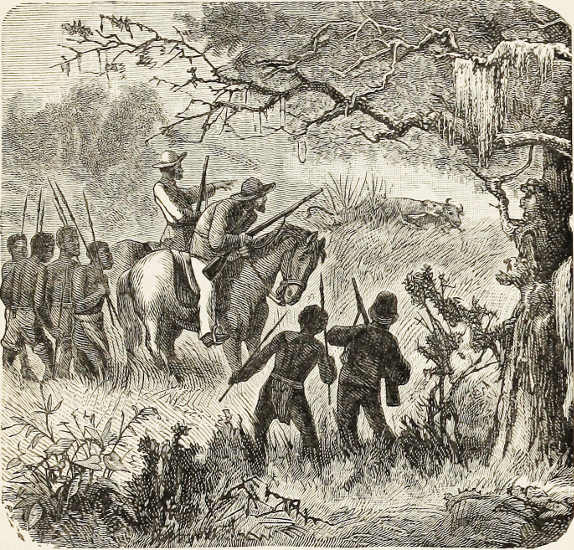

| Pursued by Matabele | 52 |

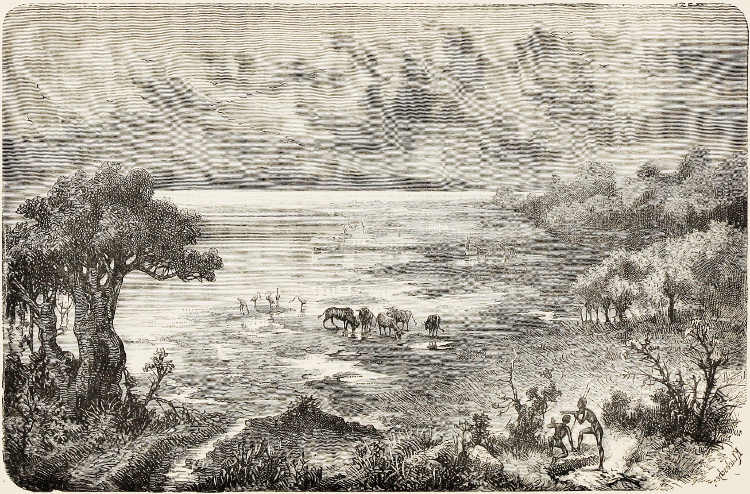

| The Soa Salt Lake | 57 |

| Hunting the Zulu Hartebeest | 62 |

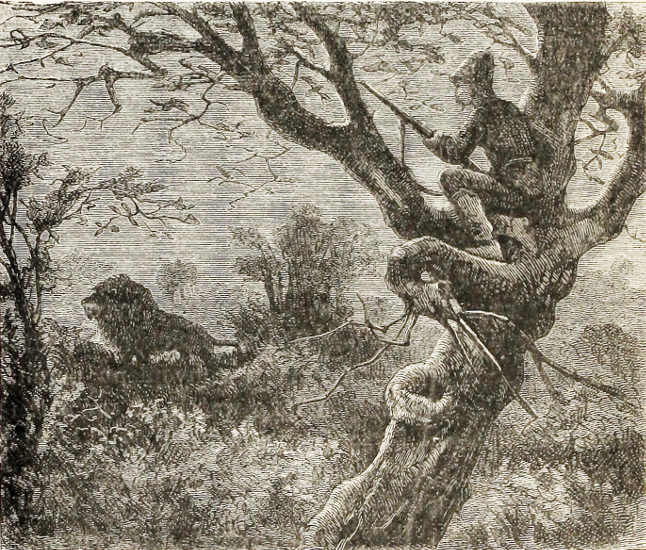

| In the Tree | 66 |

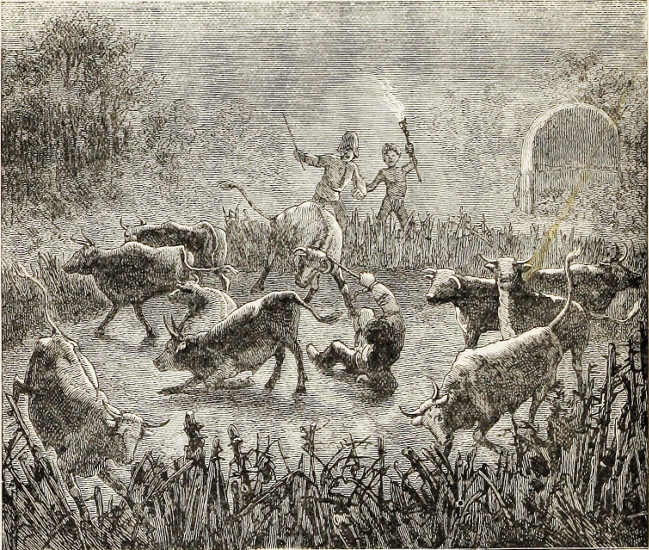

| Startled by Lions | 76 |

| “Pit, are you asleep?” | 91 |

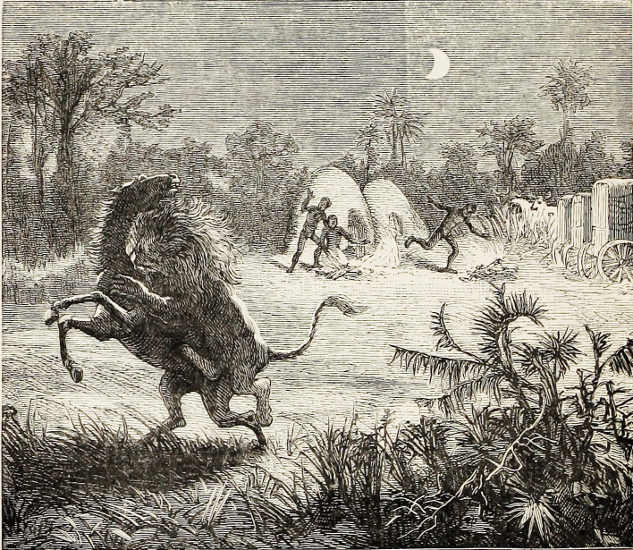

| Nocturnal Attack by Lion | 102 |

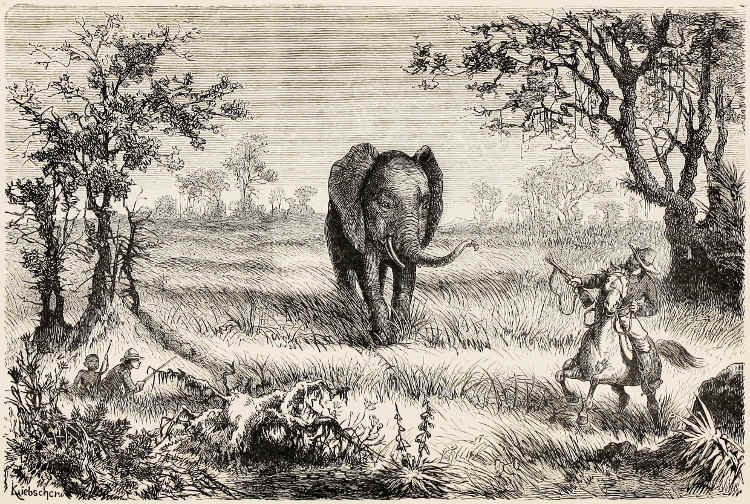

| Elephant Hunting | 107 |

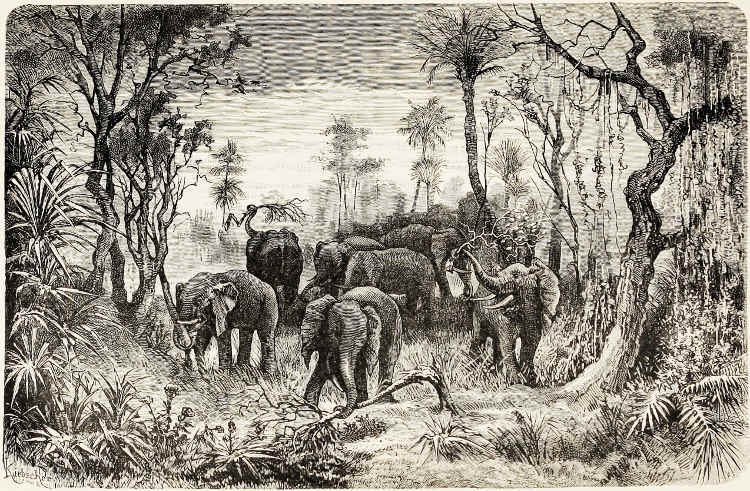

| Elephants on the March | 108 |

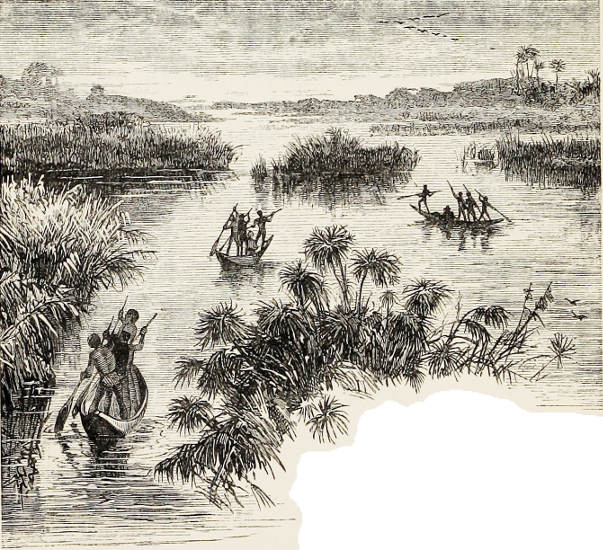

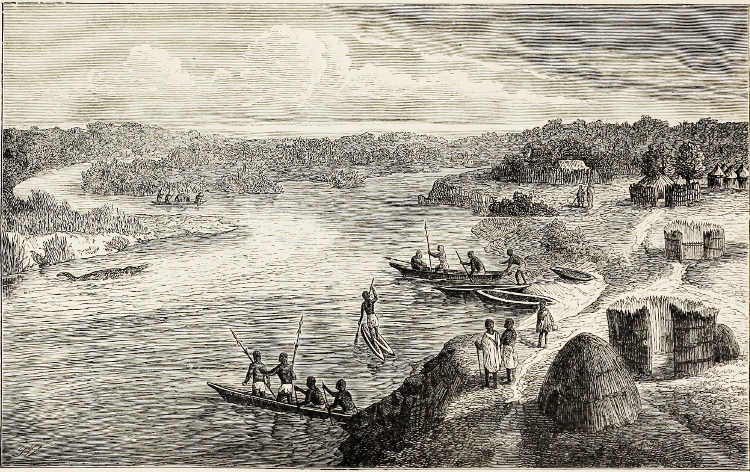

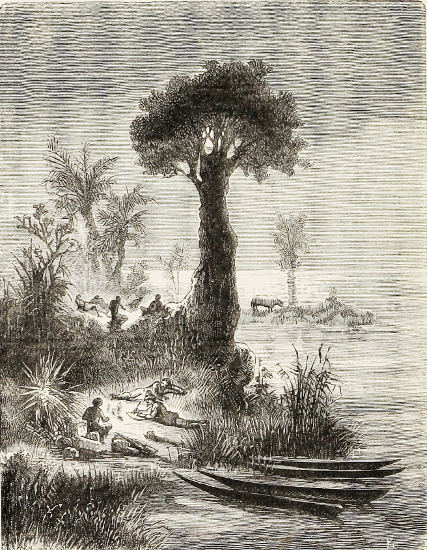

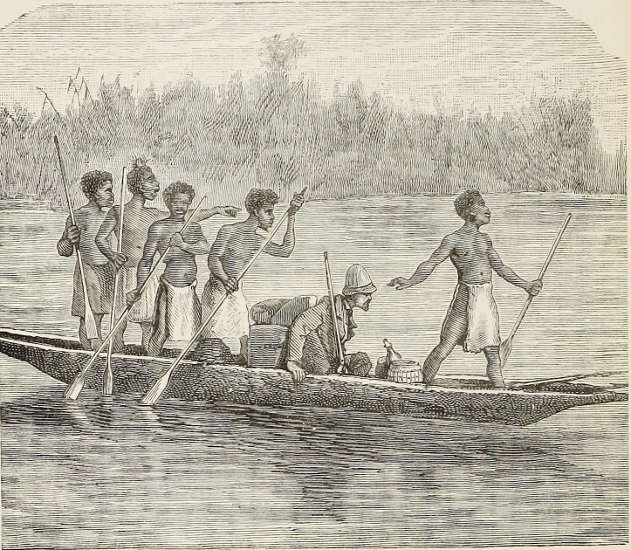

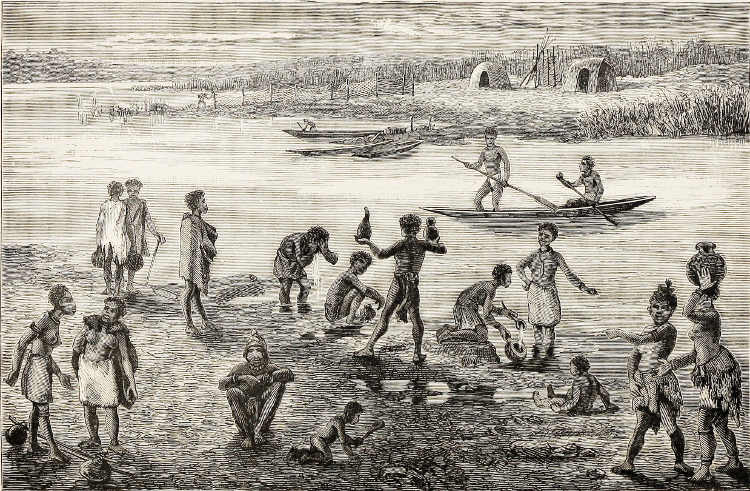

| Boating on the Zambesi | 110 |

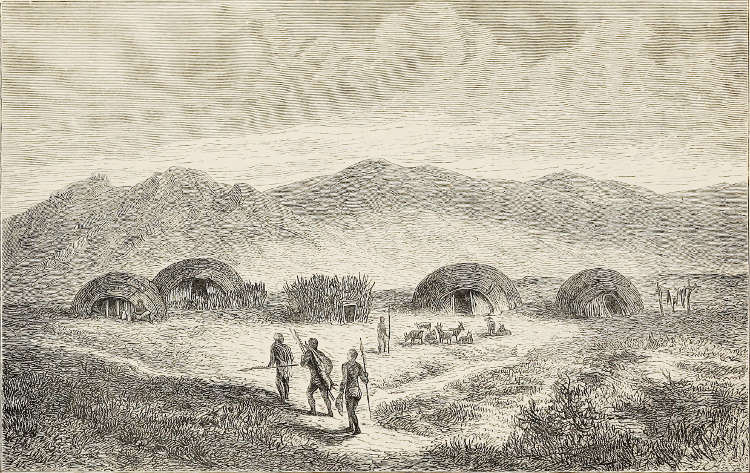

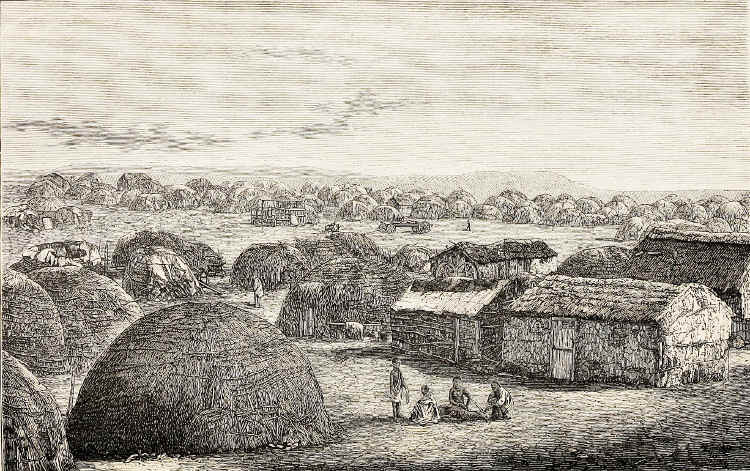

| Impalera | 111 |

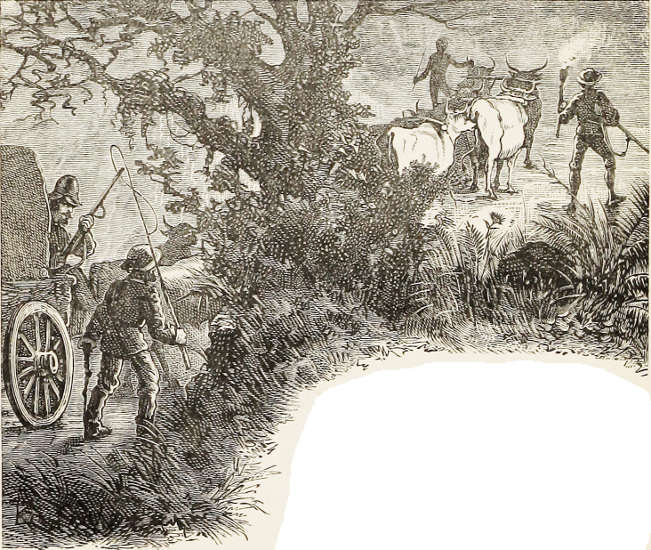

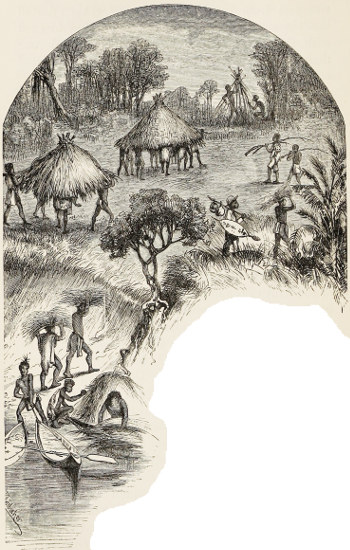

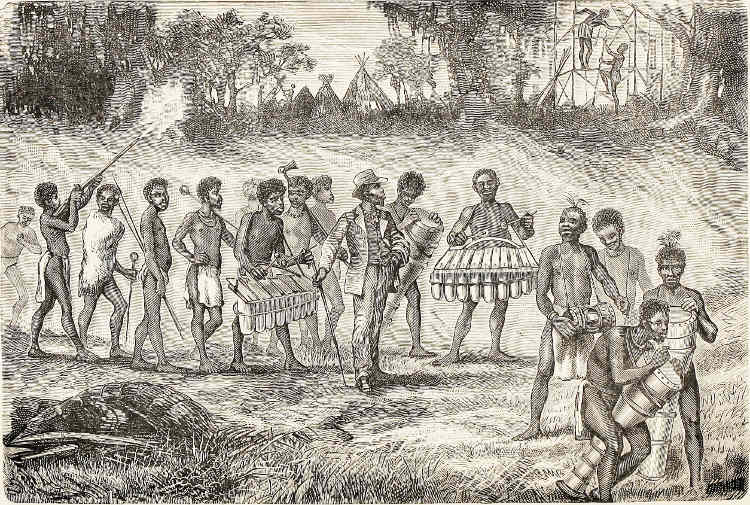

| Removal to New Sesheke | 122 |

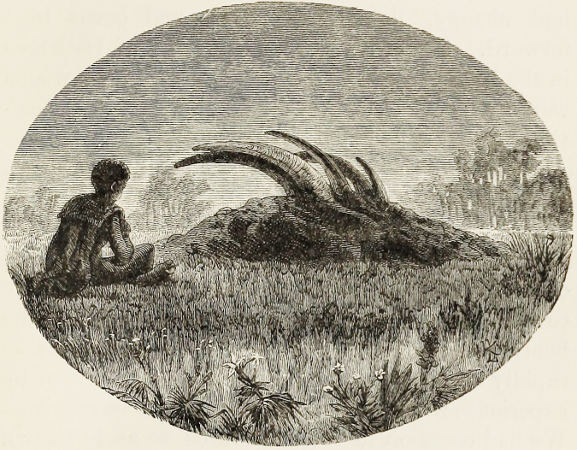

| Masupia Grave | 127 |

| On the Banks of the Chobe | 129 |

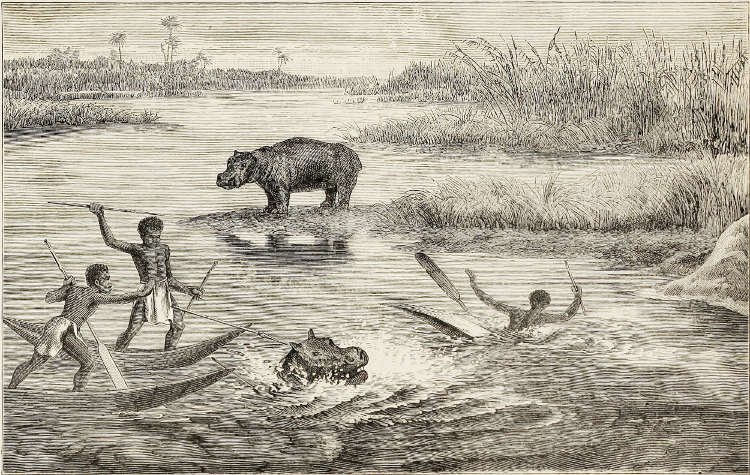

| Hippopotamus Hunting | 132 |

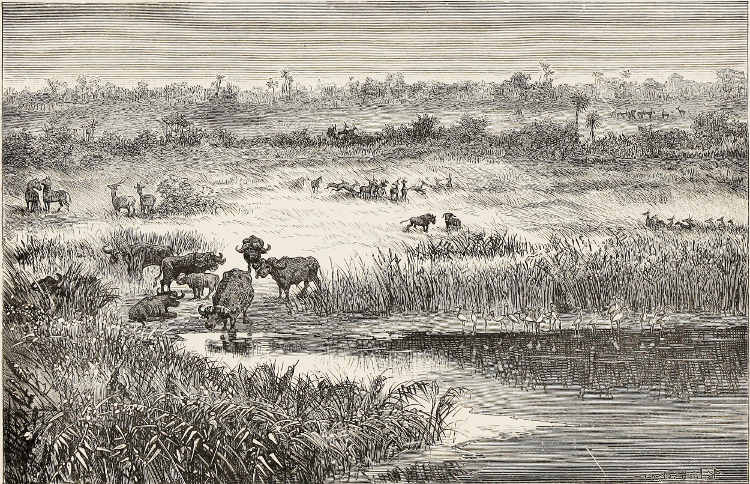

| Game Country near Blockley’s Kraal | 133 |

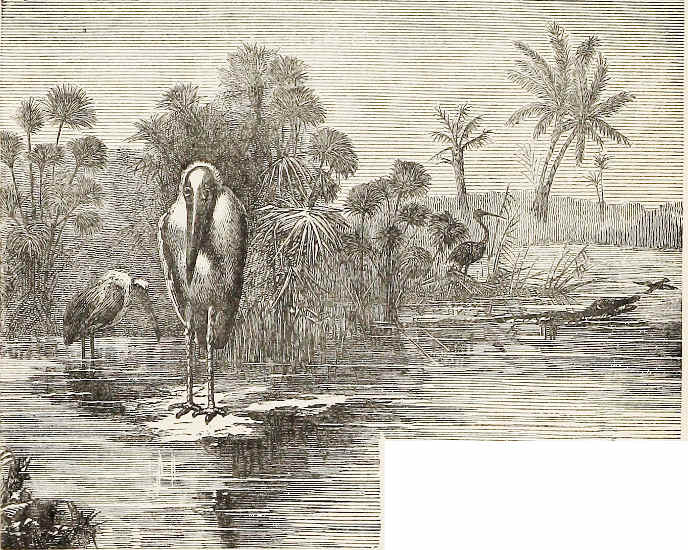

| In the Papyrus Thickets | 136 |

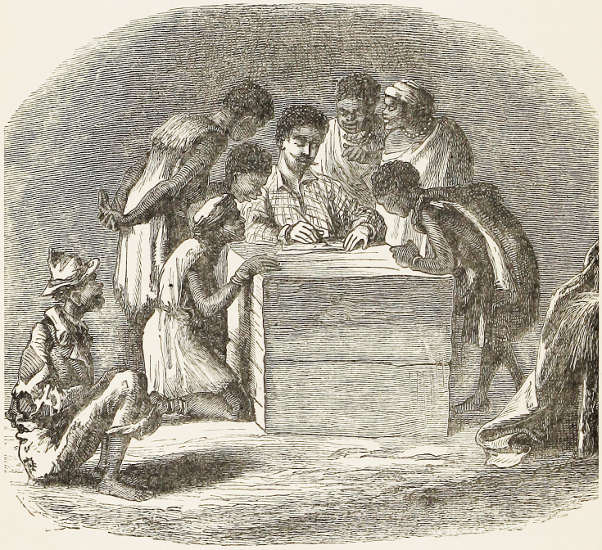

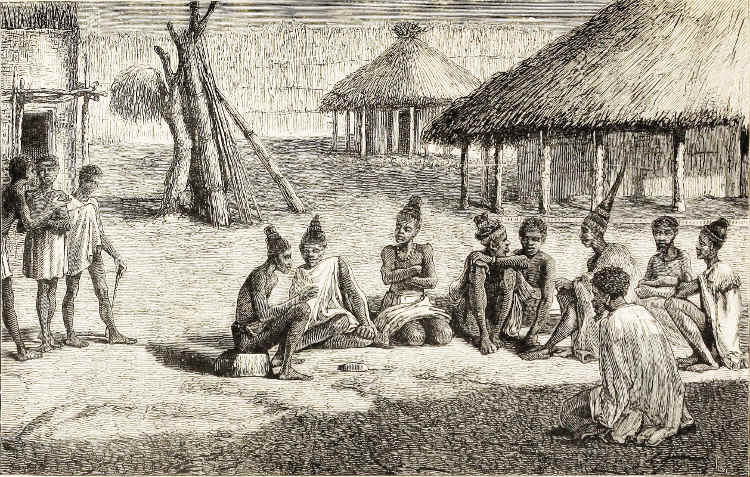

| Reception at Sepopo’s | 137 |

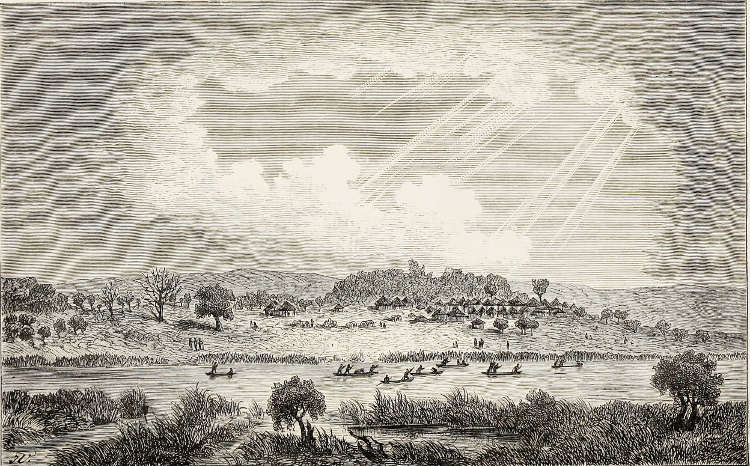

| Port of Sesheke | 140 |

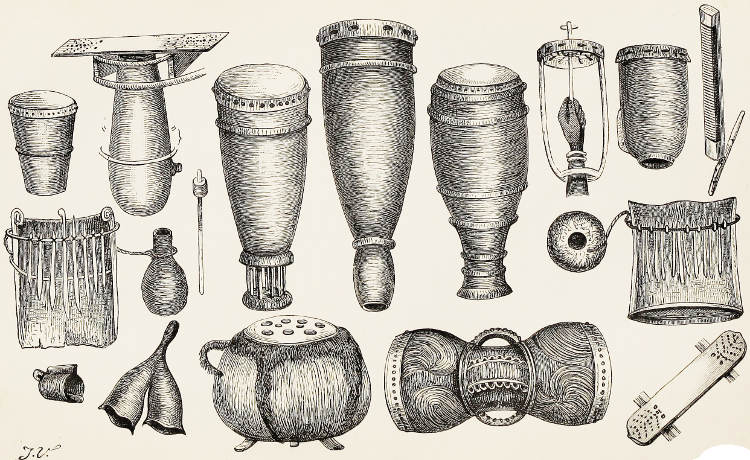

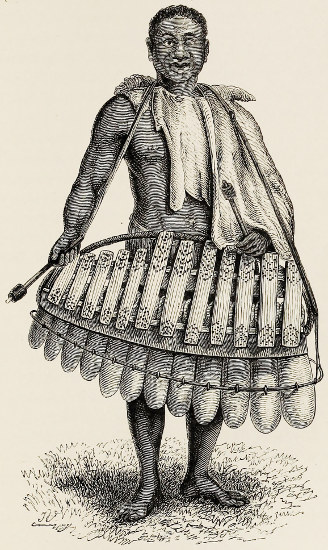

| Musical Instruments of the Marutse | 147 |

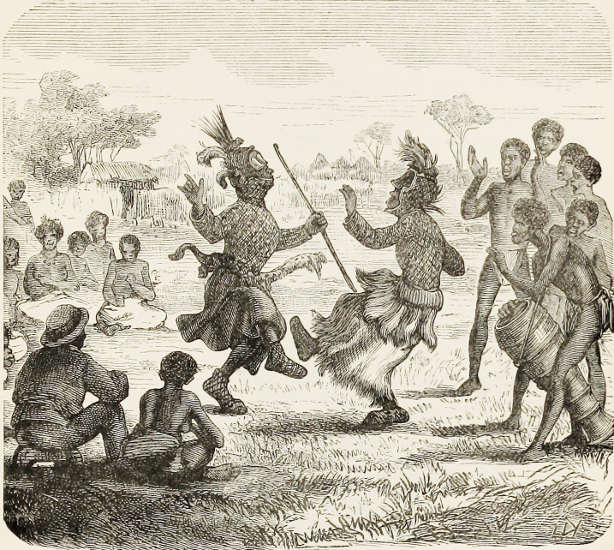

| Kishi-Dance | 169 |

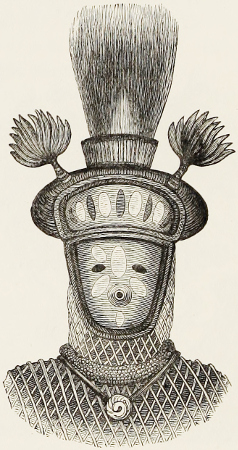

| Mask of a Kishi-Dancer | 170 |

| On the Shores of the Zambesi | 176 |

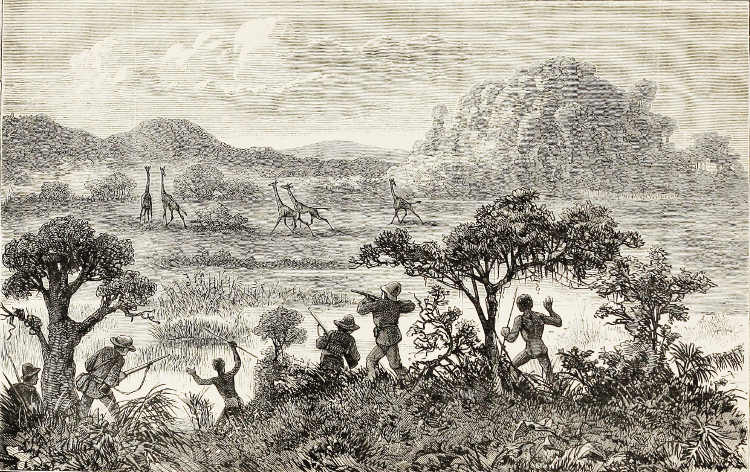

| A Troop of Giraffes surprised | 184 |

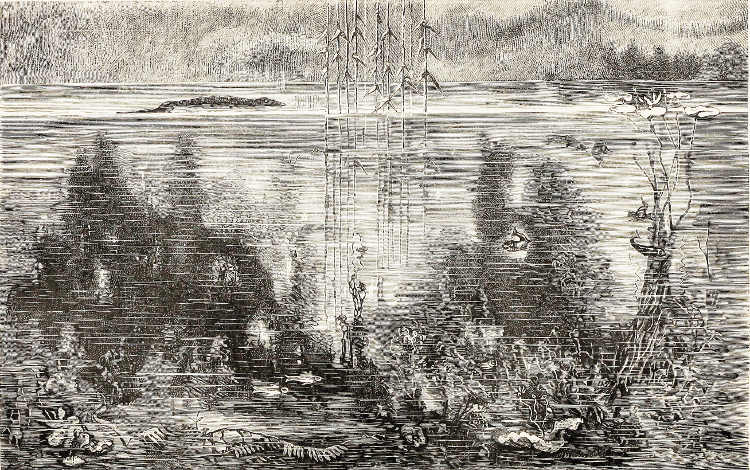

| Aquatic Life in a still Pool by the Zambesi | 187 |

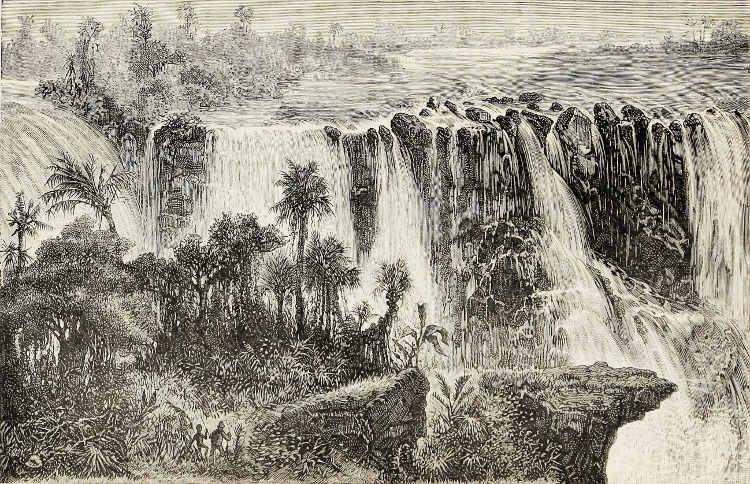

| The Victoria Falls | 194 |

| The Lion expected | 201 |

| Encounter with a Tiger | 213 |

| Hunting the Spur-winged Goose | 214 |

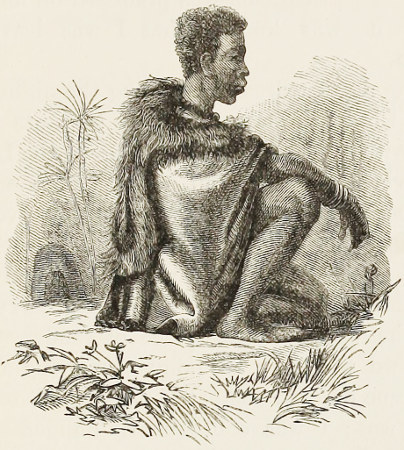

| King Sepopo | 220 |

| The Prophetic Dance of the Masupias | 229 |

| Visit of the Queens | 232 |

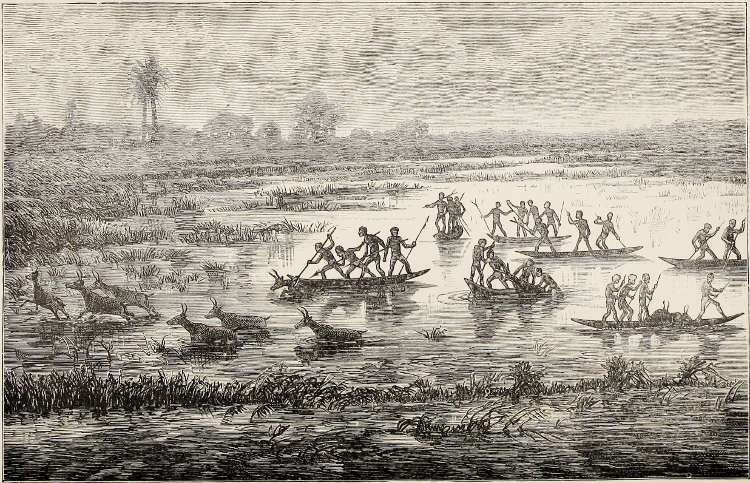

| Chase of the Water-Antelope | 249 |

| Lion Hunt near Sesheke | 253 |

| Mashukulumbe at the Court of King Sepopo | 258 |

| Sepopo’s Doctor | 264 |

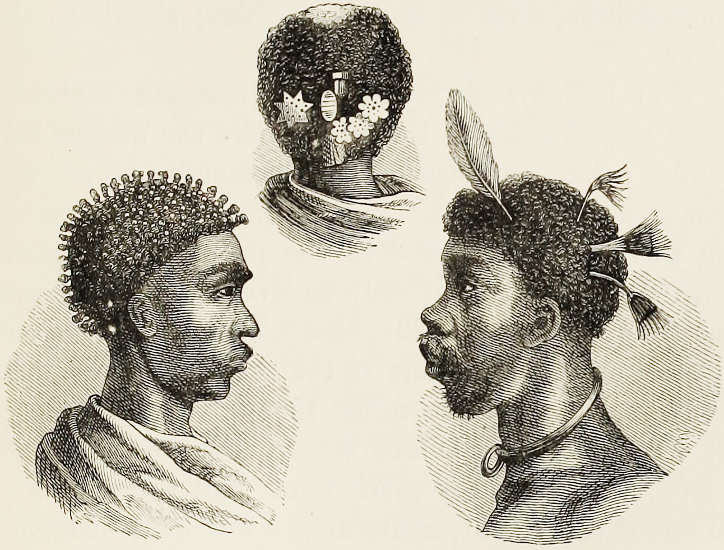

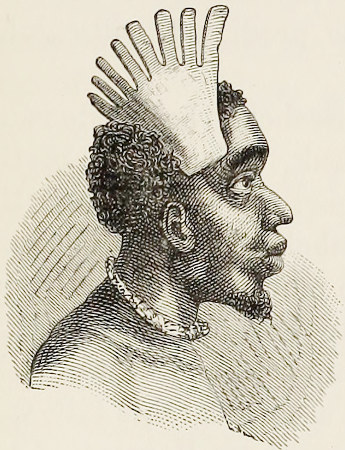

| A Mabunda. A Makololo | 265 |

| Mankoe | 266 |

| Types of Marutse | 267 |

| A Mambari. A Matonga | 271 |

| Ascending the Zambesi | 274 |

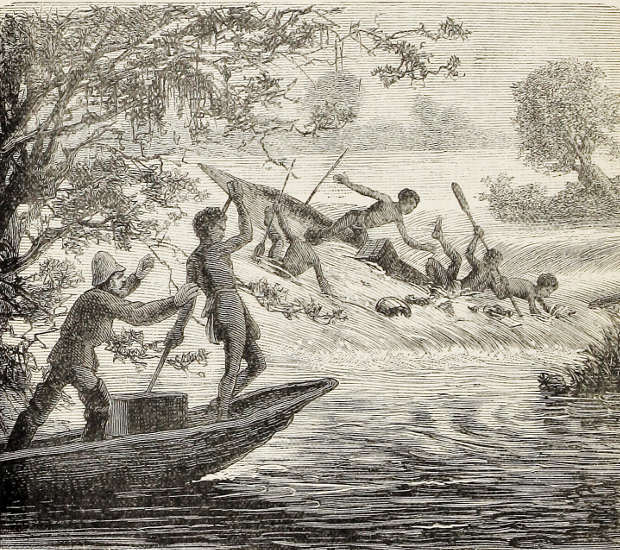

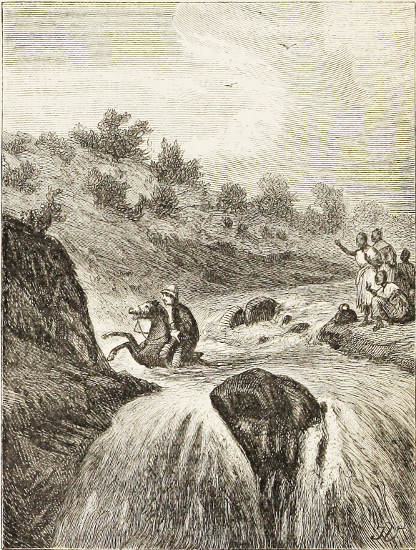

| My boat wrecked | 276 |

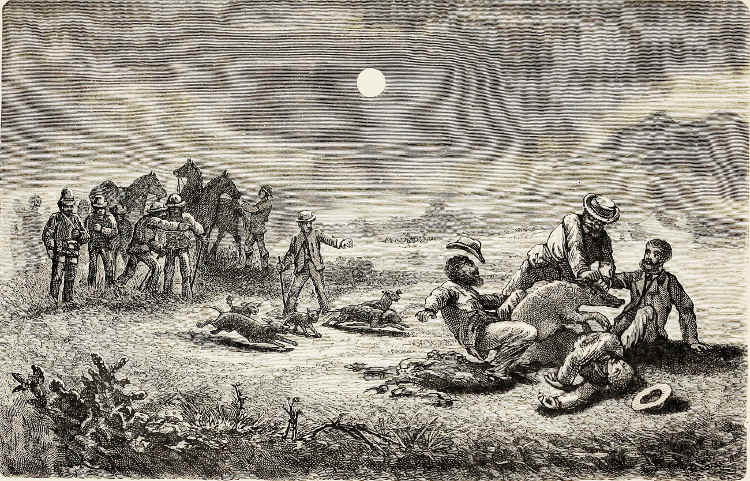

| Night Visit from Lions at Sioma | 280 |

| In the Manekango Rapids | 281 |

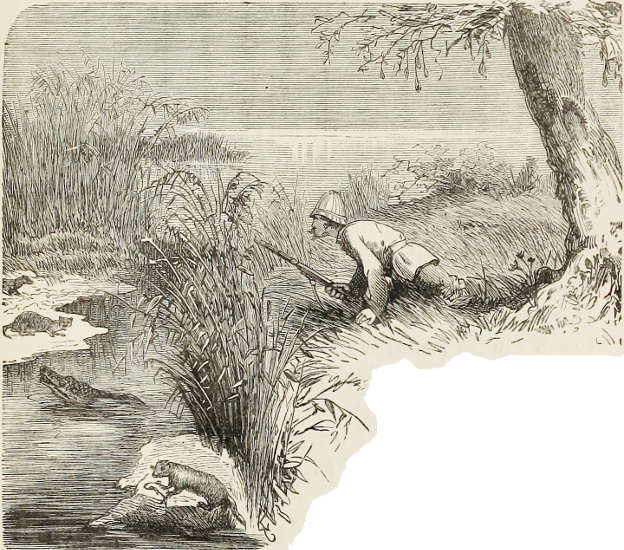

| Otter-shooting on the Chobe | 283 |

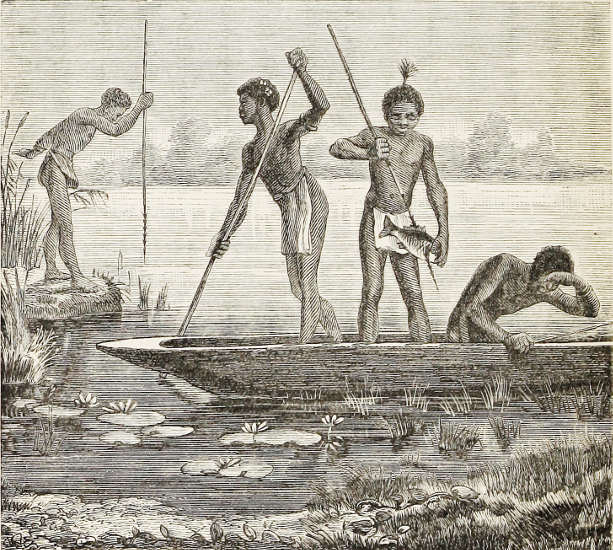

| Spearing Fish | 290 |

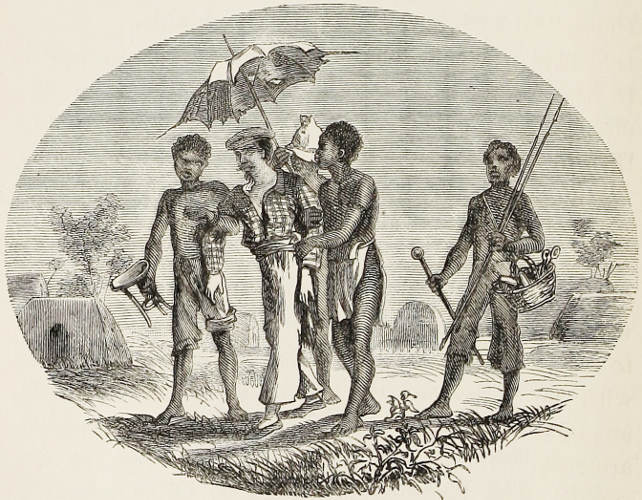

| Walk through Sesheke | 292 |

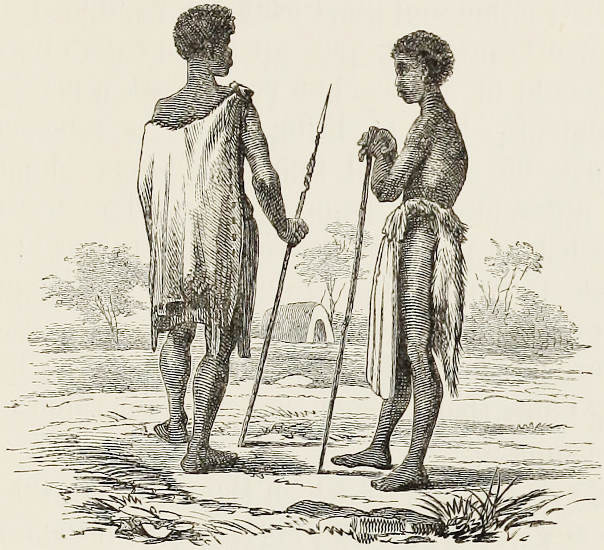

| A Masupia.—A Panda | 297 |

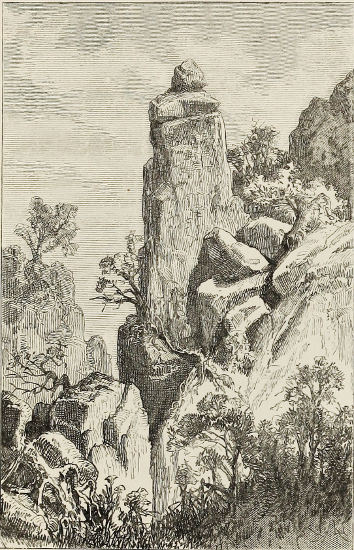

| Singular Rock | 299 |

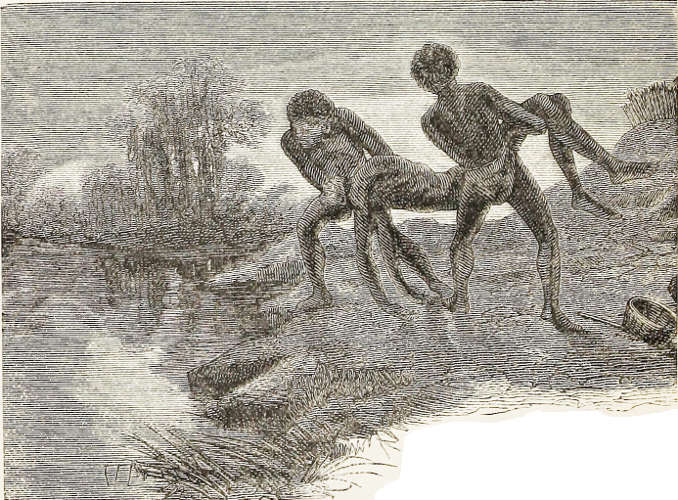

| Drowning useless People | 300 |

| Sepopo’s Head Musician | 302 |

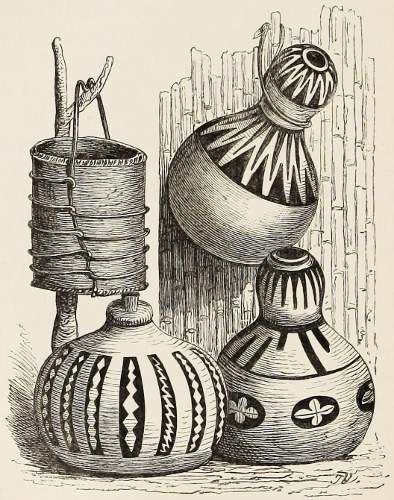

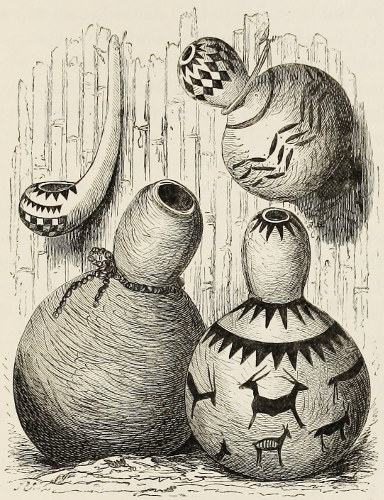

| Marutse-Mabunda Calabashes for Honey-mead and Corn | 305 |

| Bark Basket and Calabashes for holding Corn, used by the Mabundas | 308 |

| Mabunda Ladle and Calabashes | 311 |

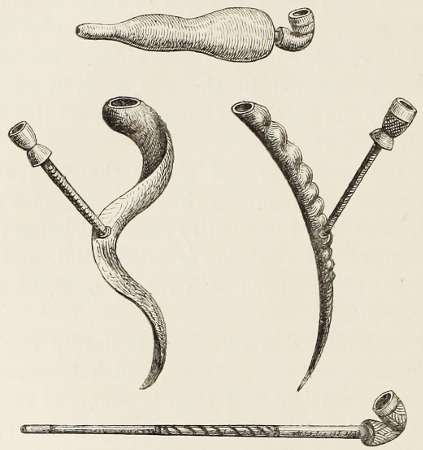

| Marutse-Mabunda Pipes | 344 |

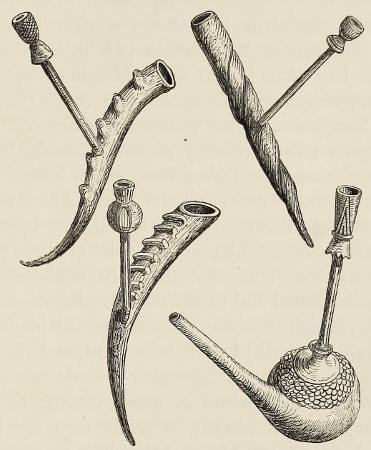

| Pipes for smoking Dacha | 345 |

| Scene on the Zambesi Shores at Sesheke | 351 |

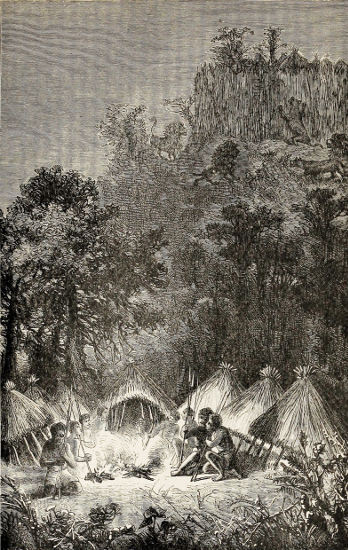

| Camp in the Leshumo Valley | 354 |

| Wana Wena, the new King of the Marutse | 357 |

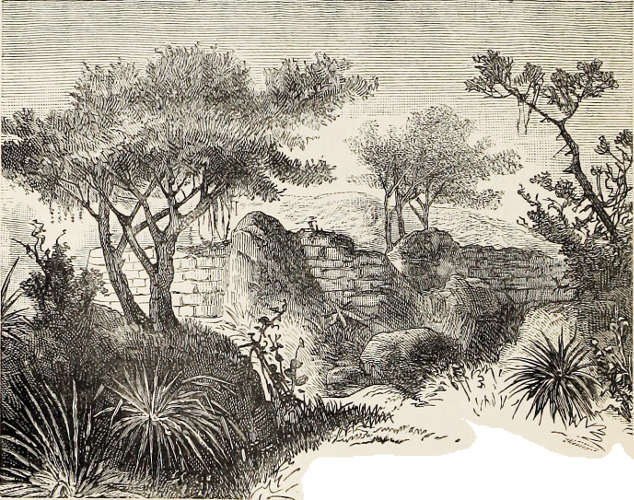

| Ruins of Rocky Shasha | 372 |

| Boer’s Wife defending her Waggon against Kafirs | 402 |

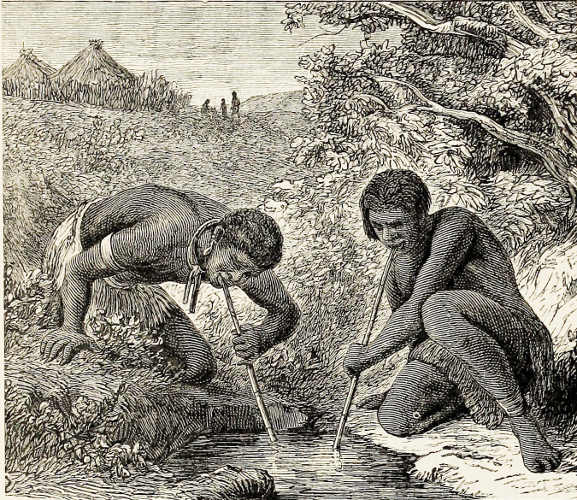

| Masarwas Drinking | 405 |

| Lioness attacking Cattle on the Tati River | 409 |

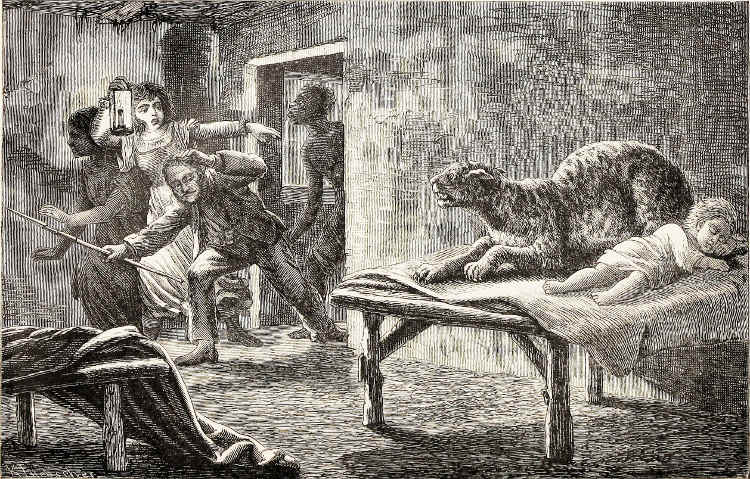

| Leopard in Pit Jacobs’ House | 415 |

| Return to the Diamond Fields | 418 |

| Koranna Homestead near Mamusa | 420 |

| Mission House in Molopolole | 424 |

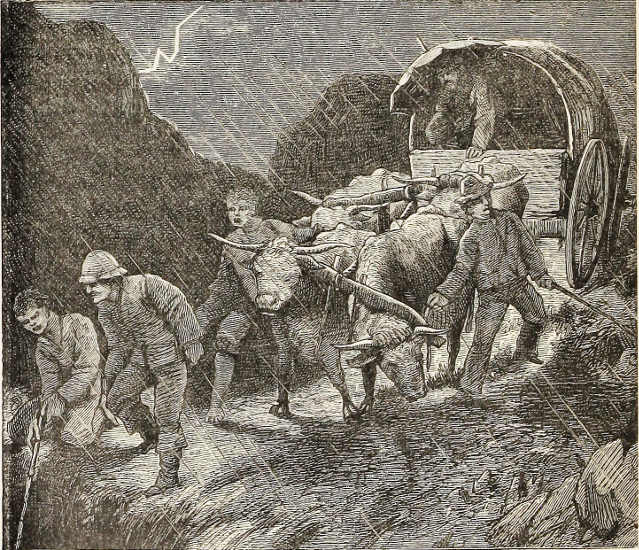

| Night Journey | 430 |

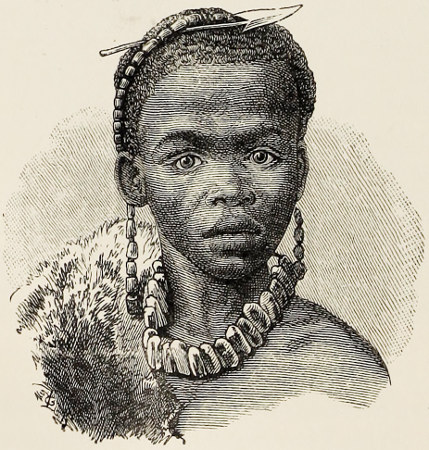

| Fingo Boy | 432 |

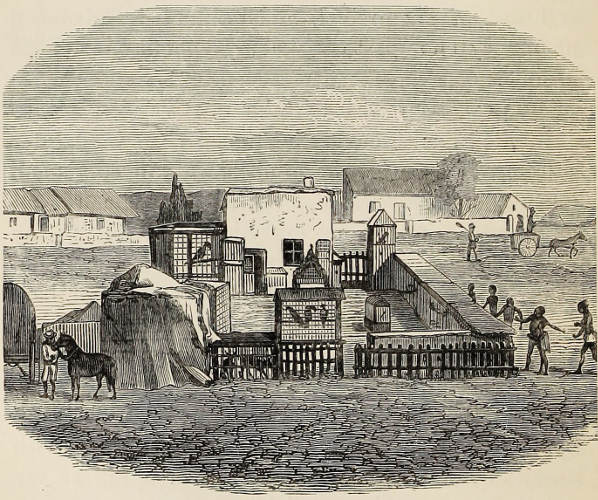

| My House in Bultfontein | 434 |

| Rock Inscriptions by Bushmen | 438 |

| Capture of an Earth-Pig | 440 |

| Colonel Warren | 449 |

| Bella | 454 |

| Narrow Escape near Cradock | 460 |

| Main Street in Port Elizabeth | 468 |

| Fingo Village at Port Elizabeth | 469 |

[1]

SEVEN YEARS IN SOUTH AFRICA.

THIRD JOURNEY INTO THE INTERIOR.

Departure from Dutoitspan—Crossing the Vaal—Graves in the Harts River valley—Mamusa—Wild-goose shooting on Moffat’s Salt Lake—A royal crane’s nest—Molema’s Town—Barolong weddings—A lawsuit—Cold weather—The Malmani valley—Weltufrede farm.

I was now standing on the threshold of my real design. After three years spent upon the glowing soil of the dark continent, the scene of the[2] endurances and the renown of many an enthusiast, I had now arrived at the time for putting into execution the scheme I had projected. My feelings necessarily were of a very mingled character. Was I sufficiently inured to the hardships that could not be separated from the undertaking? Could I fairly indulge the hope of reaching the goal for which I had so long forsaken home, kindred, and friends? The experience of my two preliminary journeys made me venture to answer both these questions without misgiving. I had certainly gained a considerable insight into the nature of the country; I had learned the character of the contingencies that might arise from the disposition of the natives and their mode of dealing, and I had satisfied myself of the necessity as well as the comfort of having trustworthy associates on whom I could rely. Altogether I felt justified in commencing what I designed to be really a journey of exploration. At the same time I could not be otherwise than alive to the probability that some unforeseen difficulty might arise which no human effort could surmount.

It was a conflict of hopes and fears, but the picture of the Atlantic at Loanda seemed to unfold itself to my gaze, and its attraction was irresistible; hitherto in my lesser enterprises I had been favoured by fortune, and why should she now cease to smile? I felt that there was everything to encourage me, and definitely resolved to face the difficulties that an expedition into the interior of Africa cannot fail to entail.

It was on the 2nd of March, 1875, that I left[3] Dutoitspan. I went first of all to a friend at Bultfontein, intending to stay with him until the 6th, and there to complete my preparations. Not alone was it my scheme to explore Southern-Central Africa, but I hardly expected to return to Cape Colony at all, consequently my arrangements on leaving this time were rather more complicated than they had been on the two previous occasions.

Quitting Bultfontein on the day proposed, I proceeded for eleven miles, and made my first halt by the side of a sandy rain-pool, enclosed by the rising ground that was visible from the diamond-fields. We slept in the mimosa woods, through which the road to the Transvaal runs for several miles, and the deep sand of which is so troublesome to vehicles.

On the 7th we passed the Rietvley and Keyle farms, around which we saw a good many herds of springbocks in the meadow-lands.

The next day’s march took us by the farms at Rietfontein, and Pan Place, and we made our night camp on Coetze’s land. Near these farms, which lay at the foot of the considerable hill called the Plat Berg, I secured some feathered game, amongst which was a partridge. To me the most interesting spot in the day’s journey was a marshy place on Coetze’s farm; it was a pond with a number of creeks and various little islands, which were the habitat of water-fowl, particularly wild ducks, moorhens, and divers. In the evening I called upon Mynheer Coetze, and in the course of conversation mentioned his ponds with their numerous birds. He surprised me somewhat by his reply. “Yes,” he said, “the birds breed there, and we[4] never disturb them; we allow strangers to shoot them, but for our own part we like to see them flying about.” I admired his sentiment, and wished that it was more shared by the Dutch farmers in general.

The property was partially wooded, and extended both into Griqualand West and into the Orange Free State. Amongst other game upon it, there was a large herd of striped gnus.

POND NEAR COETZE’S FARM.

On the next day but one we made the difficult passage of the Vaal at Blignaut’s Pont. From the two river-banks I obtained some skins of birds, and several varieties of leaf-beetles (Platycorynus).[5] At the ferry, on the shore by which we arrived, stood a medley of clay huts, warped by the wind, and propped up on all sides, claiming to be an hotel; on the further shores were a few Koranna huts, the occupiers of which were the ferrymen. For taking us across the river they demanded on behalf of their employer the sum of twenty-five shillings.

The rain had made the ground very heavy, and it was after a very tedious ride that we reached Christiana, the little Transvaal town with which the reader has been already made acquainted, and made our way to Hallwater Farm (erroneously called Monomotapa), where we obtained a supply of salt from the resident Korannas.

We next took a northerly course, and passed through Strengfontein, a farm belonging to Mynheer Weber, lying to the east of the territory of the independent Korannas. The country beyond was well pastured, and contained several farmsteads; although it was claimed by the Korannas, by Gassibone, by Mankuruane, and by the Transvaal government, it had no real ruler. The woods afforded shelter for duykerbocks, hartebeests, and both black and striped gnus, whilst the plains abounded with springbocks, bustards, and many small birds.

After passing Dreifontein, a farm that had only a short time previously been reduced to ashes by the natives from the surrounding heights, we encamped on the Houmansvley, that lay a little further ahead. Near the remains of the place were some huts, from which some Koranna women came out, their intrusive behaviour being in marked contrast[6] with that of some Batlapins, who modestly retired into the background. Not far off was a vley, or marshy pond, where I found some wild ducks, grey herons, and long-eared swamp-owls (Otus capensis). Houmansvley was the last of the farms we had to pass before we entered the territory of the Korannas of Mamusa.

GRAVES UNDER THE CAMEL-THORN TREES AT MAMUSA.

We reached the Harts River valley on the evening of the 15th. Before getting to the river we had to traverse a slope overgrown with grass, and in some places with acacias which must be a hundred years old, and under the shadow of which were some Batlapin and Koranna graves, most of them in a good state of preservation. The river-bed[7] is very often perfectly dry, but as the stream was very much swollen, the current was too strong to allow us to cross without waiting for it to subside; the district, however, was so attractive that it was by no means to be regretted that we were temporarily delayed. The high plateau, with its background of woods, projected like a tongue into the valley, and opposite to us, about three-quarters of a mile to the right, rose the Mamusa hills.

We visited Mamusa, encamping on its little river a short distance from the merchants’ offices under the eastern slope of the hills. A few years back it had been one of the most populous places representing the Hottentot element in South Africa, but now it was abandoned to a few of the descendants of the aged king Mashon and their servants. Some of the people had carried off their herds to the pasture-lands; others had left the place for good, to settle on the affluents of the Mokara and the Konana, on the plains abounding in game that stretched northwards towards the Molapo. This small Koranna principality is an enclave in the southern Bechuana kingdoms, a circumstance which is not at all to their advantage, as any mixture of the Hottentot and Bantu elements is sure to result in the degeneration of the latter.

The merchants received me most kindly. One of them, Mr. Mergusson, was a naturalist, and amused himself by taming wild birds. He showed me several piles, at least three feet high, of the skins of antelopes, gnus, and zebras, which he intended taking to Bloemhof for sale. He and his brother had twice extended their business-journeys as far as Lake Ngami.

[8]

While in the neighbourhood, I heard tidings of the two dishonest servants that I had hired at Musemanyana, and who had decamped after robbing me on my second journey.

Leaving Mamusa on the 17th, we had to mount the bushy highland, dotted here and there with Koranna farmsteads, and in the evening reached the southern end of the grassy quagga-flats. The soil was so much sodden with rain, that in many places the plains were transformed into marshes; on the drier parts light specks were visible, which on nearer approach turned out to be springbock gazelles. On every side the traveller was greeted by the melodious notes of the crowned crane, and the birds, less shy here than elsewhere, allowed him to come in such close proximity, that he could admire the beauty of their plumage. The cackle of the spurred and Egyptian geese could be heard now in one spot and now in another, and wild-ducks, either in rows or in pairs, hovered above our heads.

Our next march afforded us good sport. It was rather laborious, but our exertions were well rewarded, as amongst other booty, we secured a silver heron, some plovers, and some snipes. I had our camp pitched by the side of a broad salt-water lake, proposing to remain there for several days, the surrounding animal-life promising not merely a choice provision for our table, but some valuable acquisitions for my collection.

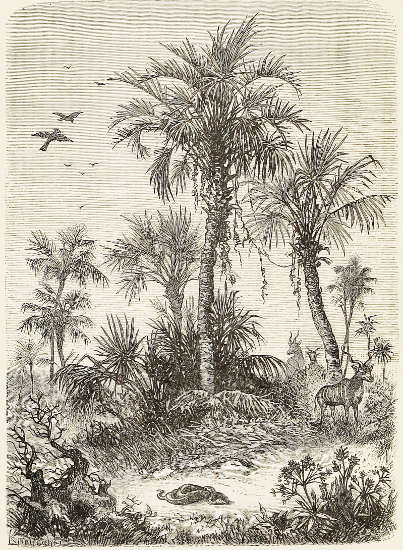

Vol. II.

Page 9.

SHOOTING WILD GEESE AT MOFFAT’S SALT PAN.

At daybreak next morning, I started off with Theunissen on a hunting-excursion. There had been rain in the night, and the air was somewhat cool, so that it was with a feeling of satisfaction that [9]I hailed the rising sun as its early beam darted down the vale and was reflected in the water. On the opposite shore we noticed a flock of that stateliest of waders, the flamingo, with its deep red plumage and strong brown beak. Close beside them was a group of brown geese wading towards us, and screeching as they came was a double file of grey cranes, whilst a gathering of herons was keeping watch upon some rocks that projected from the water. High above the lake could be heard the melodious long-drawn note of the mahem, and amidst the numbers of the larger birds that thronged the surface of the water was what seemed a countless abundance of moorhens and ducks. I stood and gazed upon the lively scene till I was quite absorbed. All at once a sharp whistle from my companion recalled me to myself. I was immediately aware of the approach of a flock of dark brown geese; though unwieldly, they made a rapid flight, their heavy wings making a considerable whirr. A shot from each of my barrels brought down two of the birds into the reeds; the rest turned sharply off to the left, leaving Theunissen, disappointed at not getting the shot he expected, to follow them towards the plain to no purpose. Great was the commotion that my own shots made amongst the denizens of the lake. Quickly rose the grey cranes from the shallow water, scarce two feet deep, and made for the shore where we were standing. In the excitement of their alarm, the crowned cranes took to flight in exactly the opposite direction; the flamingoes hurried hither and thither, apparently at a loss whether to fly or to run, until one of them catching sight of me rose high into the air, screeching[10] wildly, and was followed by the entire train soaring aloft till they looked no larger than crows; the black geese, on the other hand, left the grass to take refuge in the water, and the smaller birds forsook the reeds, as deeming the centre of the lake the place of safety.

We were not long out. We returned to breakfast, and while we were taking our meal we caught sight of a herd of blessbocks, numbering at least 250 head, grazing in the depression of the hills on the opposite shore. Breakfast, of course, was forgotten and left unfinished. Off we started; the chase was long, but it was unattended with success. Our toil, however, was not entirely without compensation, as on our return we secured a fine grey crane. Pit likewise in the course of the day shot several birds, and in the afternoon excited our interest by saying that he had discovered the nest of a royal crane.

I went to the reedy pool to which he directed me, about a mile and a half to the north of our place of encampment, and on a little islet hardly more than seven feet square, sure enough was a hollow forming the nest, which contained two long white eggs, each about the size of my fist. I took the measurement of the nest, and found it as nearly as possible thirty inches in diameter, and six inches deep.

Vol. II.

Page 11.

HUNTING AMONG THE ROCKS AT MOLEMA.

While I was resting one afternoon in a glen between the hills, I noticed a repetition of what I had observed already in the course of my second journey, namely, that springbocks, in going to drink, act as pioneers for other game, and that blessbocks and gnus follow in their wake, but only when it has been ascertained that all is safe.

[11]

To the lake by which we had been making our pleasant little stay, I gave the name of Moffat’s Salt Lake. On the 23rd we left it, and after quitting its shore, which, it may be mentioned, affords excellent hiding-places for the Canis mesomelas, we had to pass several deepish pools which seemed to abound with moorhens and divers. On a wooded eminence, not far away from our starting-place, we came across some Makalahari, who were cutting into strips the carcase of a blessbock. On the same spot was a series of pitfalls, now partially filled up with sand, but which had originally been made with no little outlay of labour, being from thirty to fifty feet long, and from five to six feet wide.

In the evening we passed a wood where a Batlapin hunting-party, consisting of Mankuruane’s people, had made their camp. They commenced at once to importune us for brandy, first in wheedling, and then in threatening tones.

Game, which seemed to have been failing us for a day or two, became on the 25th again very abundant. The bush was also thicker. A herd of nearly 400 springbocks that were grazing not far ahead, precisely across the grassy road, scampered off with great speed, but not before Theunissen had had the good luck to bring down a full-grown doe. As we entered upon the district of the Maritsana River, the bushveldt continued to grow denser, and the country made a perceptible dip to the north-west. Several rain-glens had to be crossed, and some broad shallow valleys, luxuriantly overgrown, one of which I named the Hartebeest Vale. In the afternoon we reached the deep valley of the Maritsana. On the right hand slope stood a Barolong-Makalahari village,[12] the inhabitants of which were engaged in tending the flocks belonging to Molema’s Town. The valley itself was in many parts very bushy, and no doubt abounded in small game, whilst the small pools from two feet to eight feet deep in the river-bed, here partaking of the nature of a spruit, contained Orange River fish, lizards, and crabs; two kinds of ducks were generally to be seen upon them.

As we passed through a mimosa wood on the morning after, we met two Barolongs, who not only made me aware how near we had come to Molema’s Town, but informed me that Montsua was there, having arrived to preside over a trial in a poisoning case. I had not formed the intention of going into the place, but the information made me resolve to deviate a little from my route, that I might pay my respects to the king and his brother Molema.

Descending the Lothlakane valley, where Montsua was anxious that his heir should fix his residence, we reached the town on the 28th. The Molapo was rather fuller than when I was here last, but we managed to cross the rocky ford, and pitched our camp on the same spot that I had chosen in 1873.

As soon as I heard that the judicial sitting had adjourned, I lost no time in paying my personal respects to the Barolong authorities. I found the king with Molema and several other chiefs at their midday meal, some sitting on wooden stools and some upon the ground; but no sooner were they made acquainted with my arrival, than they hastened to show signs of unfeigned pleasure, making me shake hands with them again and again. Montsua at once began to talk about the[13] cures I had effected at Moshaneng, and begged me to stay for at least a few days. After spending a short time in Molema’s courtyard, we all adjourned to the house of his son, which was fitted up in European style, and where we had some coffee served in tin cups. Molema was upon the whole strong and active, but he was still subject to fits of asthma, and requested me to supply him with more medicine like that he had had before; and so grateful was he for my services, that he gave me a couple of good draught-oxen, one of which I exchanged with his son Matye for an English saddle.

Molema is a thin, slight man of middle height, with a nose like a hawk’s beak, which, in conjunction with a keen, restless eye, gives to his whole countenance a peculiarly searching expression. At times he is somewhat stern, but in a general way he is very indulgent to his subjects, who submit implicitly to his authority; this was illustrated in the issue of the cause over which Montsua was now visiting him to preside. He is very considerate for his invalid wife, and, considering his age, he is vigorous both in mind and body; although his sons and the upper class residents of the town have adopted the European mode of fitting up their houses, he persists in adhering to the native style of architecture.

During our stay here, Mr. Webb had to perform the marriage service for three couples; one of the bridegrooms had a remarkable name, the English rendering of which would be “he lies in bed.” Singular names of this character are by no means unusual among the Bechuana children, any accidental circumstance connected with their parentage or[14] birth being seized upon to provide the personal designation for life. Taking a stroll through the place late in the evening, I heard the sound of hymns sung by four men and ten women, bringing the wedding observances to a close.

BABOON ROCKS.

Wandering about the town, I noticed that although the garments worn were chiefly of European manufacture, the inhabitants very frequently were dressed in skins either of the goat, the wild cat, the grey fox, or the duyker gazelle. Boys generally had a sheepskin or goatskin thrown across their shoulders, although occasionally the skin of a young lion took its place; girls, besides their leather aprons, nearly always covered themselves with an antelope-hide.

[15]

As far as I could learn, the disputes between the Transvaal government and the Barolongs had in great measure subsided, owing to Montsua having threatened, in consequence of the encroachments of the Boers, to allow the English flag to be planted in his villages.

I have already referred to the trial which had brought Montsua to the town, and in order that I may convey a fair idea of the way in which Bechuana justice is administered, I will give a brief outline of the whole transaction.

A Barolong, quite advanced in years, had set his affections upon a fatherless girl of fifteen, living in the town; she peremptorily refused to become his wife, and as he could not afford to buy her, he devised a cunning stratagem to obtain her. He offered his hand to the girl’s mother, who did not hesitate to accept him; by thus marrying the mother, he secured the residence of the daughter in his own quarters; the near intercourse, he hoped, would overcome her repugnance to himself; but neither his appearance nor his conversation, mainly relating to his wealth in cattle, had the least effect in altering her disposition towards him. Accordingly, he resorted to the linyaka. Aware of the pains that were being taken to force her into the marriage, the girl carefully avoided every action that could be interpreted as a sign of regard. As she was starting off to the fields one morning to her usual work, her stepfather called her back, and if her own story were true, the following conversation took place,—

“I know you hate me,” he said.

“E-he, e-he!” she assented.

[16]

“Well, well, so it must be!” he answered, but he stamped his staff with rage upon the ground.

“Yes, so it must be,” replied she.

“But you must promise me,” he continued, “that you will not marry another husband.”

“Na-ya,” she cried, bursting out laughing, “na-ya.”

“Then I’ll poison you,” he yelled.

The girl, according to her own account, was alarmed, and went and told her mother and another woman who were working close by the river. They tried to reassure her, telling her that her stepfather was only in joke, but they did not allay her apprehensions.

That very evening, while she was taking her simple supper of water-melon, he called her off and sent her on some message; when she returned she finished her meal, but in the course of an hour or two she was writhing in most violent agony. In the height of her sufferings, she reminded her mother and the friends who gathered round her of what had transpired in the morning. Her shrieks of pain grew louder and louder, and when they were silenced, she was unconscious. Before midnight she was a corpse.

The stepfather was of course marked out as the murderer; the evidence to be produced against him seemed incontestible; the old man had actually been seen gathering leaves and tubers in the forenoon, which he had afterwards boiled in his own courtyard.

The accused, however, was one of Molema’s adherents; he had served him faithfully for half a century, and Molema accordingly felt it his duty to[17] do everything in his power to protect him, and so sent over to Moshaneng for Montsua to come and take the office of judge at the trial. He was in the midst of the inquiry when I arrived.

Meanwhile, the defendant had complete liberty; he might for the time be shunned by the population, but he walked about the streets as usual, trusting thoroughly to Molema’s clemency and influence, and certain that he should be able to buy himself off with a few bullocks.

The trial lasted for two days; after each sitting the court was entertained with bochabe, a sort of meal-pap.

The evidence was conclusive; the verdict of “guilty” was unanimous. Montsua said he should have been bound to pass a sentence of death, but Molema had assured him there were many extenuating circumstances; and, taking all things into account, he considered it best to leave the actual sentence in his hands. Molema told the convicted man to keep out of the way for a few days until Montsua had ceased to think about the matter, and then sending for him, as he strolled about, passed the judgment that he should forfeit a cow as a peace-offering to the deceased girl’s next-of-kin, the next-of-kin in this case being his wife and himself!

Before quitting the place, I went to take my leave of Mr. Webb. While I was with him a dark form presented itself in the doorway, which I quickly recognized as none other than King Montsua. He had followed me, and, advancing straight to my side, put five English shillings into my hand, requesting me to give him some more of the physic[18] which had done his wife so much good at the time of my visit to Moshaneng.

On the afternoon of the 2nd of April we left Molema’s Town, to proceed up the valley of the Molapo. Next morning we passed the last of the kraals in this direction, in a settlement under the jurisdiction of Linkoo, a brother of Molema’s.

Early morning on this day was extremely cold, and the keen south-east wind made us glad to put on some overcoats. We made a halt at Rietvley, the most westerly of the Molapo farms in the Jacobsdal district, the owner of which was a Boer of the name of Van Zyl, a brother of the Damara emigrant to whom I shall have subsequently to refer.

From this point the farms lay in close proximity to each other, as far as the sources of the Molapo. The river valley extended for about twenty-two miles towards the east, retaining its marshy character throughout, but growing gradually narrower as its banks became more steep and wooded. Although its scenery cannot be said to rank with the most attractive parts of the western frontier of the Transvaal, yet, for any traveller, whether he be ornithologist, botanist, or sportsman, the valley is well worth a visit.

The waggon-track which we had been following led, by way of Jacobsdal and Zeerust, direct to the Baharutse kraal Linokana, by which I had made up my mind to pass. We kept along the road as far as Taylor’s farm, “Olive-wood-dry,” where the density of the forest and the steepness of the slopes obliged us to leave the valley, and betake ourselves to the table-land. Olive-wood-dry is unquestionably one[19] of the finest farms on the upper Molapo; it has a good garden, and is watered by one of the most important of the springs that feed the river, whilst the rich vegetation in the valley, thoroughly protected as it is from cold winds, forms quite an oasis in the plateau of the western Transvaal. A dreary contrast to this was the aspect of the Bootfontein farm, where the people seemed to vegetate rather than to thrive.

In the evening we crossed the watershed between the Orange River and the Limpopo, and spent the night near a small spruit, one of the left-hand affluents of the Malmani, which I named the Burgerspruit. Next day we entered the pretty valley of the Malmani, the richly-wooded slopes of which looked cheerful with the numerous farms that covered them.

Quitting the Malmani valley on the 5th, we journeyed on eastwards past Newport farm, along a plain where the grass was short and sour. In the east and north-east could be seen the many spurs of the Marico hills; the hills, too, of the Khame or Hieronymus district were quite distinct in the distance, all combining to form one of the finest pieces of scenery in what may be called the South African mountain system.

The slope towards the side valley, which we should have to descend in order to reach the main valley, was characterized by a craggy double hill, to which I gave the name of Rohlfsberg. Further down, I noticed a saddle-shaped eminence, which I called the Zizka-saddle. The descent was somewhat difficult, on account of the ledges of rock, but we were amply compensated by the splendid scenery, the[20] finest bit, I think, being that at Buffalo’s-Hump farm, where in the far distance rises the outline of the Staarsattel hills.

By the evening we reached the valley of the Little Marico, and the Weltufrede farm. This belongs to Mynheer von Groomen, one of the wealthiest Boers in the district. His sons have been elephant-hunters for years, and have met with exceptional success, having managed to earn a livelihood by the pursuit. In the paddock of the farm they showed me a young giraffe that they had brought home with them from one of their expeditions.

[21]

Zeerust—Arrival at Linokana—Harvest-produce—The lion-ford on the Marico—Silurus-fishing—Crocodiles in the Limpopo—Damara-emigrants—A narrow escape—The Banks of the Notuany—The Puff-adder valley.

We could see Jacobsdal from the Weltufrede farm, a few buildings on the banks of a brook, and a neat little church, being all that this embryo town of the western Transvaal had then to show. After leaving it we turned north, then north-east towards Zeerust, the most important settlement in the[22] Marico district. On our way thither we passed one of the most productive farms in the neighbourhood; it belonged to a man named Bootha, and was traversed by the Malmani, which wound its way through a low rocky ridge to its junction with the Marico.

I made a preliminary visit by myself to the little town, but we did not actually move our quarters into Zeerust till next day. It covers a larger area than Jacobsdal, and any one devoted to natural science would find abundant material to interest him in its vicinity. We, however, only remained there a few hours, and started off for Linokana, outside which we encountered Mr. Jensen, who was bringing the mail-bag from the interior. The missionary received us with the utmost cordiality, and gave us an invitation, which I accepted most gratefully, to stay with him for a fortnight; the time that I spent with him was beneficial in more ways than one, as not only did it afford me an opportunity of thoroughly exploring the neighbourhood, but it permitted my companions to enjoy a rest which already they much required.

In 1875, the Baharutse in Linokana gathered in as much as 800 sacks of wheat, each containing 200 lbs., and every year a wider area of land is being brought under cultivation. Besides wheat, they grow maize, sorghum, melons, and tobacco, selling what they do not require for their own consumption in the markets of the Transvaal and the diamond-fields; it cannot be said, however, that their fields are as carefully kept as those of the Barolongs. A great deal of their land has been transferred to the Boer government, and they only retain the ownership of a few farms.

[23]

On the 9th I went to the sources of the Matebe and wandered about the surrounding hills, where mineral ores seem to abound. The following day I employed myself in drawing out a sketch-map of my route, and when I had completed it, I amused myself by an inspection of the plantations and gardens which surround the mission-station. I attended the chapel, where the service consisted of a hymn, the reading of a portion of one of the gospels, then another hymn, followed by a sermon; the impression made upon the congregation as they squatted on their low wooden stools being very marked, and the whole service in its very simplicity being to my mind as solemn as the most gorgeous ritual.

The native postman from Molopolole arrived late on the evening of the 15th, the journey having taken him three days; he only stayed one night, and started back again with the European mail that came through Zeerust from Klerksdorf. To my great surprise it brought me a kind letter from Dr. A. Petermann, the renowned geographer at Gotha.

An English major likewise arrived from the Banguaketse countries; he was in search of ore and was now on his way to Kolobeng and Molopolole; he gave us an interesting account of the reasons that had induced him and Captain Finlayson to explore the north-eastern Transvaal.

The Baharutse girls seem to be particularly fond of dancing, and we hardly ever failed of an evening to hear music and occasionally singing in various parts of the town.

One of the most picturesque spots in the whole[24] neighbourhood is in the valley of the Notuany, about three miles below its confluence with the Matebe; it is enclosed by rocky slopes broken here and there by rich glens and luxuriant woodlands that afford cover for countless birds, whilst in the sedge-thickets on the Matebe wild cats nearly as large as leopards lurk about for their prey.

ON THE BANKS OF THE MATEBE RIVULET.

We left Linokana on the 23rd, and crossed the Notuany, a proceeding that occupied us nearly two[25] hours, as the half-ruined condition of the bridge made it necessary for us to use even more caution than on my previous journey.

I spent a pleasant day in the Buisport glen, and had some good fishing in the pools of the Marnpa stream, as well as some excellent sport on its banks. The upper pools contain many more fish and water-lizards than those near the opening of the glen, for being deeper and more shady they are less liable to get dried up. Some of the mimosas and willows that overhang the stream were sixty feet high, and as much as four feet in diameter.

Next day we passed the Witfontein and Sandfontein farms, both in the Bushveldt. The residents at Witfontein were making preparations for a great hunting-excursion into the interior, where they expressed a hope that they might meet me again. Zwart’s farm I found quite forsaken, its owner having started off on a similar errand the week before; from his last excursion he had brought back some ostriches and elands. Some Boers that we met informed me that fresh stragglers from the Transvaal were continually joining Van Zyl, and that the Damara emigrants would soon feel themselves sufficiently strong to continue their north-westerly progress; their place of rendezvous was on the left bank of the Crocodile River between the Notuany and the Sirorume.

Before the day was at an end we reached Fourier’s farm at Brackfontein, and spent the night there, encamping next day at Schweinfurth’s Pass, in the Dwars mountains. By the evening we had come as far as the springs in the rocks on the spurs of the Chwene-Chwene heights, whence we skirted the[26] town of Chwene-Chwene itself, and after crossing the valley on the Bechuana spruit, took up our quarters on the northern slope of the spur of the Bertha hills. On the banks of the spruit I noticed a deserted Barwa village containing about fifteen huts; they lay in an open meadow, and consisted merely of bundles of grass thrown like a cap over stakes about five feet long bound together at their upper ends.

The Great Marico was reached on the afternoon of the 30th. We made our encampment at a spot where a couple of diminutive islands, projecting above the rapid, made it possible to get across without any danger from crocodiles. The probability of there being an abundance of game on the opposite side induced me to stay for two or three days. Regardless of Pit’s warning that he had seen a lion’s track close by, I selected a place some hundred yards lower down, and resolved to go and keep watch there for whatever game might turn up. I took the precaution to enclose the spot with a low fence.

Soon after sunset I proceeded to carry out my intention. The passage of the river with its somewhat strong current in the dark was troublesome as well as fatiguing. I reached my look-out, which I found by no means comfortable, and as the darkness gathered round me, I became conscious of a strange yearning for my distant home, and the image of my mother seemed to arise so visibly before me, that I could hardly persuade myself that she was not actually approaching. Phantasies of this kind were altogether unusual with me, and as the sense of awe appeared to increase, I began to debate with myself whether I had not better[27] retire from my position and make my way back to the waggon. It came, however, to my recollection that this was just the hour when the crocodiles left the water and made their way to the banks, in order to avoid the rapids.

The night continued to grow darker, and dense masses of cloud rose up to obscure the sky. I came to the final decision that my watch would be to no purpose, and was just about setting out to return, when I became aware of the movement of some great object scarcely ten yards away. Of course in the dark no reliance was to be placed upon my gun; my long hunting-knife was the only weapon on which I had to depend; this I grasped firmly, and stooped down, straining every power of vision to penetrate the gloom; but nothing was to be discerned; only a strange and inexplicable glimmer still moved before my eyes. Again, with startling vividness, the image of my mother rose before me; I could not help interpreting it to betoken that some danger was near, and once more I determined to hasten back at all hazards to our encampment. I placed my foot upon the twigs with which I had built up my fence, and it came down with a crash which sounded sufficiently alarming. Gun in one hand, and knife in the other, I proceeded to grope my way along, but recollecting that my gun was useless, and finding it an incumbrance, I threw it into a bush; after it had fallen I heard a noise like scratching or scraping, and I am much mistaken if I did not distinguish a low growl, and it occurred to me that it was more than likely that some beasts of prey had been stealthily making their way to my place of retreat. Having no longer the shelter[28] of my fence-work I confess a feeling of tremor came over me, and my heart beat very fast. Still slashing about with my hunting-knife, I cut my way through the overhanging boughs, pausing at every step, and listening anxiously to every sound. In spite of all my care I came from time to time into collision with the branches, and I staggered in wonder whether I had not at last encountered some gigantic beast of prey.

It took me a considerable time to get over that hundred yards by which I was separated from the stream, but at length I accomplished it, and reached a narrow rain-channel, that facilitated my descent to the brink of the water. It was with extreme caution that I placed one foot before another, as my sole clue to the direction of the ford was derived from the increase or decrease in the sound of the current; more than once I lost my footing, and fell down bodily into the water, but after a time, with much difficulty, managed to get on to the first of the two islands; upon this I did not rest for a minute, but plunged at once into the main stream, whence I succeeded in gaining the second island. Here I paused long enough to recover my somewhat exhausted breath, and then re-entering the seething waters, tottered over the slippery stones till I found myself safely on the shore. As I set my foot upon the ground I could not do otherwise than experience a great sense of relief, although I was quite aware that there might be danger yet in store. I was so tired that I should have been glad to throw myself upon the ground then and there, but the chance of exposing myself to the crocodiles at that hour was too serious to be risked.

[29]

Just as I was on the point of clambering up the bank I heard a rustling above my head; I kept perfectly silent, and soon discovered that the noise came from a herd of pallahs, on their way to drink. I recognized them by the crashing which their horns made in the bushes, and by their peculiar grunt. Swinging myself up by means of the branches, I reached the top of the bank, and wending my way along the glen, before long recognized the barking of the dogs, which had been disturbed by the antelopes. My whistle quickly brought my faithful Niger to my side, and his company agreeably relieved the rest of my way back to the fires which marked the place of our encampment.

Taking Pit with me next morning, I made an investigation of the place where I had spent so much of the previous dreary night. It was covered with lion-tracks, and the little barricade was completely trampled down. One of my dogs at this place fell a victim to the flies, that settled in swarms on its eyes, ears, and nose, so that the poor brute was literally stung to death.

Shortly afterwards I took Pit on another long excursion inland. Having heard that the colonists are accustomed to creep into the large hyæna-holes under ground, and that when they have ascertained that the hyæna is “at home,” they kindle a fire at its mouth, so that the animal is obliged to make an exit, when it is either shot or killed by clubs, I made Pit put the experiment into practice. We found the hole, and we lighted the fire, but we did not secure our prey; somehow or other Pit was not able to make the smoking-out process go off successfully.

[30]

We continued our journey the same day. A few miles down the river I met an ivory-trader from the Matabele country, who had instructions from the Matabele king to convey the intelligence to the English governor in Kimberley that a white traveller had been killed amongst the Mashonas, on the eastern boundary of his domain.

I had throughout the day noticed such a diversity of birds, reptiles, insects, plants, and minerals, that I was further disposed to try my luck at fishing, and taking my tackle, I lost no time in dropping my line into the river. I succeeded in hooking three large sheat-fish, the smallest of which weighed over six pounds, but they were too heavy for me to drag to land; two of them broke my line, and the other slipped back into the stream. I had almost contrived to get a fourth safely ashore, when my foot slipped, and overbalancing myself, I fell head foremost down the bank; happily a “wait-a-bit” bush prevented my tumbling into the river.

Guinea-fowl I observed in abundance everywhere along the Marico, in parts where the bushes were thick; but I noticed that they never left their roosting-places until the heavy morning dew was dry. The speed at which they ran was quite incredible.

Proceeding on our way we came up with several Bechuana families belonging to the Makhosi tribe, who had been living on Sechele’s territory, near the ruins of Kolobeng; but they had been so much harassed by Sechele that they were now migrating, and about to settle at the foot of the Dwars Mountains. Sechele had been preparing an armed attack upon both the Makhosi and the Bakhatlas, but the[31] latter having gained intelligence of his scheme, took prompt measures to resist him, and made him abandon the design. It is in every way desirable, both for traders and travellers, as well as for the neighbouring colonies, that the integrity of the six existing Bechuana kingdoms should be maintained. Any splitting-up into smaller states would be attended with the same inconveniences as the European colonists and travellers have to suffer on the east coast north of Delagoa Bay.

Whilst we were passing through the light woods of the Marico on the 4th, we caught sight of a water-bock doe in the long grass. Theunissen stalked it very adroitly, but unfortunately his cartridge missed fire, and before Pit could hand him a second, the creature took to flight. In spite of our having had frost for the last two days, the morning was beautifully fine.

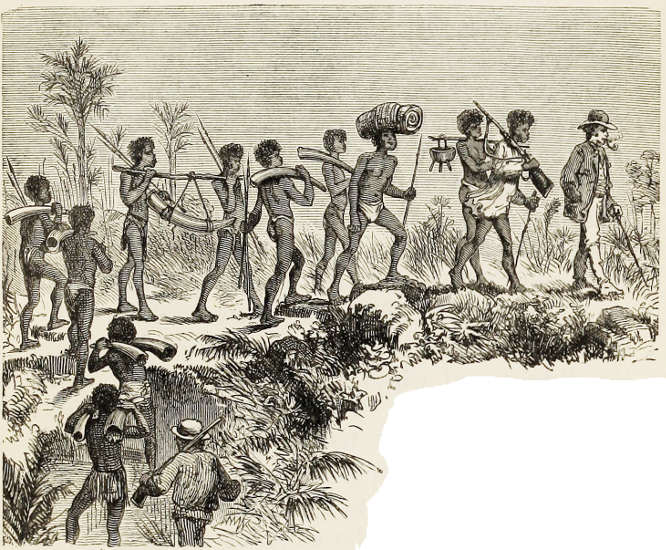

Leaving the Marico, only to rejoin it again at its mouth, we traversed the triangular piece of wood which lies between it and the Limpopo. On our way we fell in with a party of Makalakas, who were reduced almost to skeletons, having travelled from the western Matabele-land, 500 miles away, for the purpose of hiring themselves out at the diamond-fields, each expecting in six months to earn enough to buy a gun and a supply of ammunition. We were sorry not to be able to comply with their request that we would give them some meat, but as it happened we had not killed any game for several days.

The next morning found us on the Limpopo; and as I purposed staying here for a few days, we set to work and erected a high fence of mimosa boughs,[32] for the greater security of our bullocks. In the afternoon Theunissen and I made an excursion, in the course of which we shot two apes and four little night monkeys, that were remarkable for their fine silky hair and large bright eyes. As a general rule they sleep all day and wake up at night, when they commence spending a merry time in the trees, hunting insects and moths, eating berries, and licking down the gum of the mimosas.

CROCODILE IN THE LIMPOPO.

One of our servants had a rencontre that was rather alarming, with one of the crocodiles, from which the river derives its name. He was washing[33] clothes upon the bank, when a dark object emerged from the water, startling him so much that he let the garment slip from his hands. He called out, and had the presence of mind to hurl a big stone at the crocodile’s head, and succeeded in clutching the article back just as the huge creature was snapping at it. An adventure of a somewhat similar character happened to myself. Finding that the Limpopo was only three feet deep just below its confluence with the Marico, I determined to make my way across. We felled several stout mimosa stems, and made a raft; but the new wood was so heavy that under my weight it sank two feet into the water. Convinced that my experiment was a failure, I was springing from one side of the raft on to the shore, when a crocodile mounted the other side—an apparition sufficiently startling to make me give up the idea of crossing for the present.

Taking our departure on the 7th, we proceeded down the stream, having as many as fifteen narrow rain-channels to pass on our way. The whole district was one unbroken forest, and we noticed some very fine hardekool trees. On the left the country belonged to Sechele, on the right to the Transvaal republic.

Though our progress was somewhat slow, being retarded by the sport which we enjoyed at every opportunity, we reached the mouth of the Notuany next evening, having passed the first of the two encampments where the Damara emigrants were gathering together their contingent. It contained about thirty waggons, and at least as many tents; large herds of sheep and cows, under the care of armed sentinels, were grazing around, while the[34] people were sitting about in groups, some drinking coffee and some preparing their travelling-gear. I was rather struck by the circumstance that nearly all the women were dressed in black. Some of the men asked us whether we had seen any Boer waggons as we came along; and on our replying that we had passed a good many emigrants, they expressed great satisfaction, and said that their numbers would now very soon be large enough to allow them to start. They all declared their intention to show fight if either of the Bamangwato kings attempted to molest them or oppose their movements. When I spoke to them about the difficulty they would probably experience in conducting so large a quantity of cattle across the western part of the kingdom, where water was always very scarce, they turned a deaf ear to all my representations. It was just the same with the emigrants at the other camp, whom I saw at Shoshong on my return; they would pay no attention to any warning of danger; nothing could induce them to swerve from their design.

When I pressed my inquiries as to their true motive in migrating, they told me that the president had taken up with some utterly false views as to the interpretation of various passages in the Bible, and that the government had commenced forcing upon them a number of ill-timed and annoying innovations. If their fathers, they said, had lived, and grown grey, and died, without any of these new-fangled notions being thrust upon them, why should they now be expected to submit to the novelties against their will? And another thing which they felt to be peculiarly irritating was, that these state[35] reforms were being brought about by a lot of foreigners, and chiefly by a clique of Englishmen. What President Burgers was aiming at effecting would have an effect the very reverse of remedying the deep-seated evils that oppressed them. It seemed to me that the project which they considered the most obnoxious was that for the formation of a railroad which should connect Delagoa Bay with the Transvaal.

Were it not for their own statements, it would be quite incredible that men, who already have had to struggle hard for their property and farms, should for trivial reasons such as these, and at the instigation of one man, give up their homes and wander away into the interior. The first troop of them, without including stragglers, soon amounted to seventy waggons. They were anxious to get possession of the fine pasturage on the Damara territory, and prepared, in the event of opposition, to drive the Damaras away altogether. They experienced so much difficulty through the scarcity of water, that, after reaching Shoshong, they had to return to the Limpopo, and wait until after a plentiful rain had fallen upon the country they had to traverse.

Under the impression that the emigrants intended to purchase whatever land they required, both the Bamangwato kings granted them a safe pass across their dominions; but as soon as it transpired that they were going to establish themselves by force of arms, Khame immediately withdrew his promise. He could not see why his own territory might not be subject to a like invasion. This led the emigrants openly to avow their determination,[36] in the event of a long drought, to overcome the Matabele Zulus, otherwise they would have to fight their way through the eastern Bamangwatos.

At the end of my journey, after my return to the diamond-fields in 1877, I took up this matter publicly, anxious to do anything in my power to prevent any overt conflict between the emigrants and the noble Bamangwato king. The tenour of my views will be apprehended from the concluding paragraph of my first article, published in the Diamond News of March 24th: “It is absurd for people like these Boers, who are not in a condition to make any progress whatever in their own country, and who regard the most necessary reforms with suspicion, to think of founding a new state of their own.”[1]

Two months after writing that article, I heard they were in expectation of securing the friendship of Khamane, while he was living with Sechele at enmity with Khame. Their scheme of raising him to the throne failed, and no better success attended them in their subsequent attempt to form an alliance with Matsheng.

During 1876 and the following year, the condition of the emigrants, as they still lingered about the Limpopo, changed decidedly for the worse; they had ceased to talk about the conquest of a hostile country, but on the contrary took every means to avoid a battle; many of them had succumbed to fever, and sickness continued to make such ravages amongst them that they resolved to start once more. Again they applied to Khame for a safe passage through his land, but made a move in the direction[37] of the Mahalapsi River, instead of to Shoshong, in order to mislead him. Khame meanwhile kept himself all ready for a battle; he drilled his people every day; and having kept spies on the watch, he soon learnt that the emigrant party had fallen into a state of complete decay; but instead of taking advantage of their condition, and seizing their cattle and property, he sent Mr. Hepburn to ascertain the facts of the case; and when he found that the statements already brought to him were confirmed, he renewed his guarantee to them that they should traverse his country in security; he was really afraid that they would fail in the strength to move on at all. Their difficulties increased every day. Between Shoshong and the Zooga the district is one continuous sandy forest, known amongst the Dutch hunters as Durstland; it contained only a few watering-places for cattle, most of these being merely holes in the sand or failing river-beds; dug over night, they would only contain a few buckets full of water in the morning; and this was all the provision they had for their herds; their bullocks, consequently, became infuriated, and ran away, so that when the concourse reached the Zooga they were in a most helpless plight.

Their want of servants, too, was very trying. I saw quite little children leading the draught-oxen, and young girls brandishing the cumbrous bullock-whips. By slow and painful degrees, however, sadly diminished in numbers by sickness, and having suffered the loss of half their goods, they reached Lake Ngami, only to begin another march as tedious and fatal as that they had already accomplished. At last, what might almost be described as a troop of[38] helpless orphans reached Damara, the sole representatives of the wild and ill-fated expedition.

In London in the present year (1880) I heard that the survivors of this wild enterprise were in a condition so destitute that the English Government, assisted by free-will offerings from the Dutch and English residents, had sent out to them several consignments of food and clothing, despatched by steamer, viâ Walvisch Bay. Such was the end of the undertaking originated by a party of headstrong men, who, in ignorant opposition to reform, and from motives of political ill-feeling, rushed with open eyes to the destruction that awaited them.

Before reaching the Notuany, I had found out that the game which at the time of my last visit had been very abundant on the Limpopo, had been considerably reduced by the continual hunting carried on by the emigrants. I found only a few traces of hippopotamuses and some giraffe-tracks in the bushes by the footpath down by the river, but neither had I opportunity for hunting myself, nor did I wish to reveal their existence to the Boers.

During one of our excursions I had a narrow escape of my life. We were chasing a flock of guinea-fowl that were running along in front of us, one of which kept rising and looking back upon us. Coming to a broadish rain-channel about twelve feet in depth, and much overgrown with long grass, I called out to Theunissen, who was close behind me, to warn him to be careful how he came; but his attention was so entirely engrossed by the bird of which he was in pursuit that he did not hear me, and at the very edge of the dip he stumbled[39] and fell forward. His rifle was at full cock, ready for action; his finger slipped and touched the trigger; the bullet absolutely grazed my neck. Another eighth of an inch and I must have been killed on the spot.

To explore the neighbourhood, we remained for a few days upon the banks of the Notuany. I first went southwards down to the confluence of the river with the Limpopo. In striking contrast to the time of my previous visit, when the entire district seemed teeming with game, I had now to wait long under the shade of the mimosas before getting any sport at all; at length a solitary gazelle bounded out of the grass in front of me, and as I was all ready with a charge of hare-shot, I soon put an end to its graceful career. Some Masarwas, dependents of Sechele, residing in the wood close at hand, brought me some pallah-skins, of which I made a purchase.

The shores both of the lower Marico and the Limpopo are composed of granite, gneiss, and grey and red sandstone, the last often containing flints; these rocks sometimes assume very grotesque forms; one, for example, on the bank of the Limpopo, being called “The Cardinal’s Hat;” occasionally they contain also greenstone and ferruginous limestone. To the first spruit running into the Notuany above the Limpopo I gave the name of Purkyne’s Spruit. Some of the mimosas here were ten feet in circumference; here and there I noticed some vultures’ nests, and the trees were the habitat of many birds, amongst which we noticed Bubo Verreauxii and maculosus, Coracias caudata and C. nuchalis and parrots.

I left the Notuany a day sooner than I intended,[40] moving about four miles down the valley of the Limpopo, where the country seemed to promise me some desirable acquisitions. On the 14th, I secured the skins of two cercopithecus, one sciurus, two guinea fowl, and two francolins. An ape that I shot was disfigured and no doubt painfully distressed by two great swellings like abscesses. It was impossible to go a hundred yards along the bank of the river without seeing a crocodile lift its head above the water, to submerge it again just as quickly.

When we quitted the river-side, we proceeded to cross the wooded heights, sandy on one side, rocky on the other, that would bring us to the valley of the Sirorume. On our way, Niger enjoyed the excitement of chasing two spotted hyænas that crossed the path, but he did not succeed in overtaking either of them. By the middle of the day we reached the pond which I have already mentioned as lying on the top of these heights, and soon afterwards found ourselves descending towards the river. The name of Puff-adder valley, which I had given the place, seemed still as appropriate as ever, for we killed two of these snakes that were lying rolled up together just where we passed along. Following a Masarwa track that I remembered in search of water, I came upon a pool some ten feet deep; fastening my cap to my gun-strap, I was about to dip my extemporized bucket below the surface, when I caught sight of something glittering half in and half out of the water, which proved to be another puff-adder trying in vain to escape from a hole.

To judge from the tracks, I should be inclined to say that leopards are almost as abundant as snakes, the thorn-bushes and the crevices in the rocks[41] affording them precisely the kind of hiding-places that they delight in.

In the course of our next day’s march we came to a Bamangwato station. Sekhomo had not had sufficient men at his disposal to keep a station there; the consequence was that Sechele at that time looked upon the locality as his hunting-ground. It appeared to abound not only with giraffes, koodoos, elands, and hartebeests, but likewise with gazelles and wild swine, and numbers of hyænas and jackals.

I reached Khame’s Saltpan on the 17th, and had the bullocks taken to drink at the cisterns in the rocks. Some Bamangwato and Makalahari people were passing by, from whom I obtained several curiosities, amongst which was a remarkable battle-axe. I came across some of the venomous horned vipers, which fortunately give to the unwary notice of their presence by the loud hissing they make.

In the evening five gigantic Makalakas came to the waggon, hoping that I should engage them as servants, but I was too well acquainted with their general character to have anything to do with them.

We remained at the salt-pan until the 19th, and reached Shoshong quite late at night. The town was much altered since my last visit. Khame, after his victory, had set it on fire, and had rebuilt it much more compactly nearer the end of the glen in the Francis Joseph valley. The European quarter was now quite isolated. I was delighted to meet Mr. Mackenzie again, and he kindly invited me to be his guest during the fortnight that I proposed spending in the place.

[42]

Khame and Sekhomo—Signs of erosion in the bed of the Luala—The Maque plains—Frost—Wild ostriches—Eland-antelopes—The first palms—Assegai traps—The district of the Great Salt Lakes—The Tsitane and Karri-Karri salt-pans—The Shaueng—The Soa salt-pan—Troublesome visitors—Salt in the Nataspruit—Chase of a Zulu hartebeest—Animal life on the Nataspruit—Waiting for a lion.

IT was quite obvious that since my previous visit a great change for the better had taken place in the social condition of the Bamangwatos. At that time Sekhomo had been at the head of affairs, and, indefatigable in promoting heathen orgies, had been the most determined opponent of every reform that had tended to introduce the benefits of civilization. Khame, his eldest son, who had now succeeded him, was the very opposite of his father; the larger number of the adherents who had followed him into his voluntary banishment had returned with him and placed themselves under his authority, so that the population of the town was increased threefold. Khame’s great measure was the prohibition of the sale of brandy; it was a proceeding on his part that not only removed the chief incentive to idleness, but conduced materially to the establishment of peace and order, and made it considerably easier [43]for him to suppress the heathen rites that had been so grievously pernicious.

Vol. II.

Page 43.

BATTLE ON THE HEIGHTS OF BAMANGWATO.

In company with Mr. Mackenzie I paid several visits to Khame, and had ample opportunity of becoming acquainted with his good qualities. My time was much occupied with excursions, in working out the survey of my route between Linokana and Shoshong, and in medical attendance upon sick negroes. Khame offered me one of his own servants to accompany me to the Zambesi, and upon whom I could rely to bring back my waggon to Shoshong, if I should determine to go further north. As remuneration for the man’s services, I was to give him a musket.

Mr. Mackenzie pointed out to me the various places that had been of any importance in the recent contest between the kings. I have already mentioned how Khame, on leaving the town, had been followed by the greater number of the Bamangwatos to the Zooga river, where the district was so marshy that the people were decimated by fever, and Khame was forced to abandon the settlement he had chosen. Resolved to return to Shoshong, he proceeded to assert his claim, not in any underhand or clandestine manner, but by a direct attack upon his father and brother. He openly appointed a day on which he intended to arrive; and advancing from the north-west, made his way across the heights to the rocks overhanging the glen, and commanding a strong position above the town. Sekhomo meanwhile had divided his troops into two parts, and leaving the smaller contingent to protect the town, posted the main body so as to intercept Khame’s approach. Augmented as it was by the[44] people of the Makalaka villages, Sekhomo’s army in point of numbers was quite equal to that of his son; but, as on previous occasions, these Makalakas, fugitives from the Matabele country, proved utterly treacherous; although they professed to be Sekhomo’s allies, they had sent a message of friendship to Khame, assuring him that they should hold themselves in readiness to welcome him at the Shoshon pass. Khame’s attack was so sudden that Sekhomo’s troops were completely disorganized, and before they had time to recover themselves and commence a retreat, the conqueror took advantage of the condition of things to bring his men on to the plateau where the Makalakas had been posted. These unscrupulous rascals being under the impression that Khame’s people had been worsted, and being only anxious to get what cattle they could find, opened a brisk fire, a proceeding which so exasperated the Bamangwatos that they hurried up their main contingent, and having discharged a single volley, set to and felled the faithless Makalakas with the butt ends of their muskets.

In contrast to the incessant rain which had marked my previous visit, the drought was now so protracted that my cattle began to get rather out of condition, but not enough to prevent my starting for the Zambesi on the 4th of June. We proceeded up the Francis Joseph valley, and turning northwards, reached the high plateau on the following day by the way of the Unicorn pass. The scenery was very pretty, the sides of the valley being ever and again formed of isolated rocks, adorned most picturesquely with thick clumps of arboreal euphorbiaceæ.

[45]

On the 6th our course led us across a plain, always sandy and occasionally wooded; and it was quite late in the evening when we reached the Letlosespruit, a stream which never precipitates itself over the granite boulders with much violence, except after heavy rain. The upper strata of the adjacent hills, where ground game is abundant, consist in considerable measure of red sandstone, interspersed with quartzite and black schist, the lower being entirely granite.

The limit of our next day’s march was to be the pools at Kanne. Ranged in a semicircle to our right were more than thirty conical hills, connecting the Bamangwato with the Serotle heights. There was a kraal close to the pools, and the natives, as soon as they were aware of our approach, drove their cattle down to drink, so that by the time we arrived all the water was exhausted, and fresh holes had to be dug.

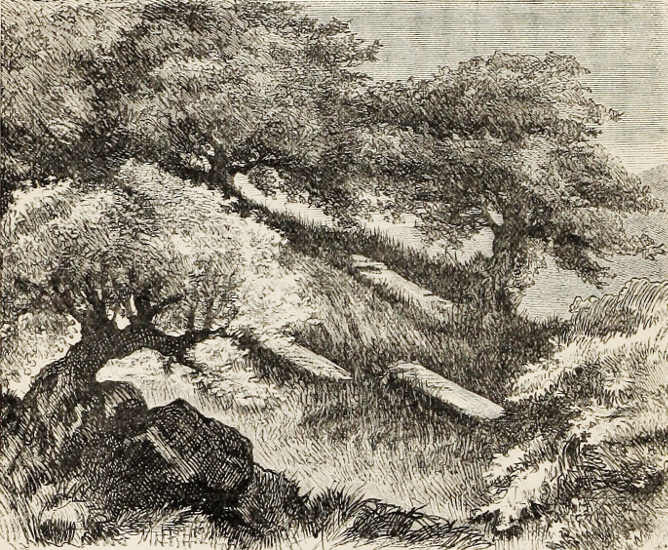

On the 8th we reached the valley of the Lualaspruit, where the vegetation and surrounding scenery were charming. The formation of the rocks, and especially the signs of erosion in the river-bed were very interesting; in one place were numerous grottoes, and in another were basins or natural arches washed out by the water, which nevertheless only flowed during a short period of the year. The ford was deep and difficult. On crossing it I met with two ivory-traders, one of whom, Mr. Anderson, had been formerly known to me by name as a gold-digger; they had been waiting camped out here for several days, while their servants were ascertaining whether the district towards the Maque plain was really as devoid of water as it[46] had been reported. The Luala and its affluents were now quite dry, and water could only be obtained by persevering digging. Mr. Anderson’s people brought word that the next watering-place could not be reached in less than forty-eight hours, and I immediately gave orders for food enough for two days’ consumption to be cooked while we had water for our use. We fell in with Mr. Anderson’s suggestion that we should travel in his company as far as the salt-lakes.

GROTTOES OF THE LUALA.

[47]

After ascending the main valley of the little river, on the evening of the 10th we reached the sandy and wooded plateau thirty miles in length, that forms a part of the southern “Durstland.” The scarcity of water in front of us made it indispensable that we should hurry on, and after marching till it was quite dark, we only allowed ourselves a few hours’ rest before again starting on a stage which continued till midday, when the excessive heat compelled us once again to halt. No cattle could toil through the deep sandy roads in the hottest hours of the afternoon, so that rest was then compulsory. By the evening, however, we had reached the low Maque plains, remarkable for their growth of mapani-trees; in all directions were traces of striped gnus, zebras, and giraffes, and even lion-tracks in unusual numbers were to be distinctly recognized. We came across some Masarwas, who refused to direct us to a marsh which we had been told was only a few miles away to the right; they were fearful, they said, of being chastised by the Bamangwatos, if it should transpire that they had given the white men any information on such a matter.

The whole of the Maque plain, which is bounded on the west by table-hills, and slopes down northwards to the salt-lake district, consists entirely of mould, equally trying to travellers at all seasons of the year, being soft mire during the rains, and painfully dry throughout the winter season. In the hands of an European landowner, however, that which now serves for nothing better than a hunting-ground might soon be transformed into prolific corn-fields and remunerative cotton-plantations.

[48]

By the time we reached the pools our poor bullocks were quite done up. The ivory-traders had pushed on in front and reached the place before us.

We were here overtaken by a messenger from Khame, who had been despatched to visit all the Bamangwato farms, and to leave the king’s instructions that no hunters should be allowed upon any pretext whatever to remain at any watering-place for more than three days. This prohibition had been brought about by the conduct of the Boers, who had been going everywhere killing the game in the most indiscriminate manner for the sake of their skins, and leaving their carcases for the vultures. The order was probably reasonable enough, but it came at an unfortunate time for us, as the natives at once took us for hunters, and consequently were occasionally far from conciliatory in their behaviour. The very spot where we had encamped had been visited by the Boers only about two months before, and we found a number of the forked runners on which they had dragged the animals behind their waggons.

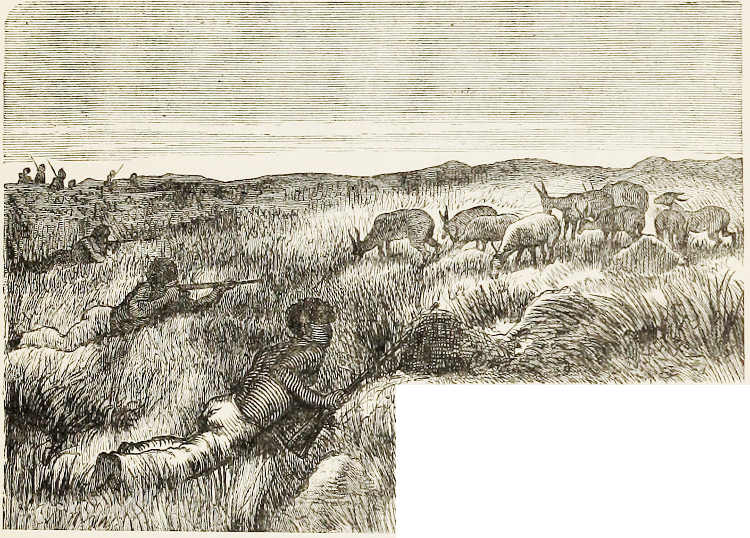

Vol. II.

Page 49.

TROOP OF OSTRICHES.