BOOKS BY E. ALEXANDER POWELL

Published by CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

| THE LAST FRONTIER: The White Man’s War for Civilization in Africa. Illustrated. 8vo | net $1.50 |

| GENTLEMEN ROVERS. Illustrated. 8vo | net $1.50 |

| THE END OF THE TRAIL. Illustrated. 8vo | net $3.00 |

| FIGHTING IN FLANDERS. Illustrated. 12mo | net $1.00 |

| THE ROAD TO GLORY. Illustrated. 8vo | net $1.50 |

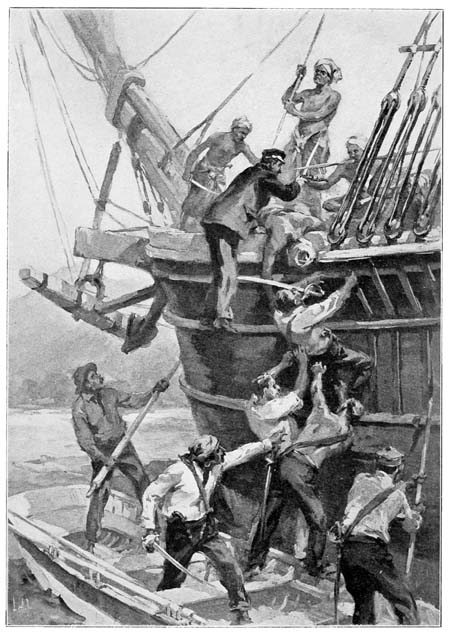

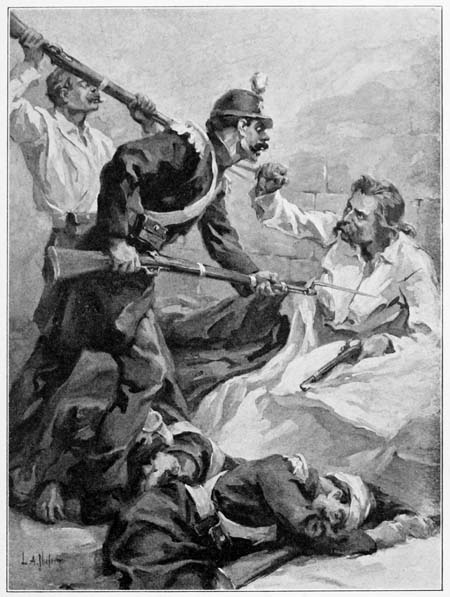

On the decks above were three hundred desperate and well-armed natives.

(Page 144)

THE ROAD TO

GLORY

BY

E. ALEXANDER POWELL

ILLUSTRATED

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

NEW YORK:::::::::::::::::::1915

Copyright, 1915, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Published September, 1915

TO MY SON

EDWARD ALEXANDER POWELL, III

The great painting—it is called “Vers la Gloire,” if I remember rightly—reaches from floor to ceiling of the Pantheon in Paris. Across the huge canvas, in a whirlwind of dust and color, sweeps an avalanche of horsemen—cuirassiers, dragoons, lancers, guides, hussars, chasseurs—with lances levelled, blades swung high, banners streaming—France’s unsung heroes in mad pursuit of Glory.

That picture brings home to the youth of France the fact that the nation owes as great a debt of gratitude to men whose very names have been forgotten as to those whom it has rewarded with titles and decorations; it teaches that a man can be a hero without having his name cut deep in brass or stone; that time and time again history has been made by men whom the historians have overlooked or disregarded.

This is even more true of our own country, for three-fourths of the territory of the United States was won for us by men whose names are without significance to most Americans. Nolan, Bean, Gutierrez, Magee, Kemper, Perry, Toledo, Humbert, Lallemand, De Aury, Mina, Long—these[viii] names doubtless convey nothing to you, yet it was the persistent and daring assaults made by these men upon the Spanish boundaries which undermined the power of Spain upon this continent and paved the way for Austin, Milam, Travis, Bowie, Crockett, Ward, and Houston to effect the liberation of Texas. On the other side of the Gulf of Mexico the Kempers, McGregor, Hubbard, and Mathews harassed the Spaniards in the Floridas until Andrew Jackson, in an unofficial and almost unrecorded war, forced Spain to cede those rich provinces to the United States. In a desperate battle with savages on the banks of an obscure creek in Indiana, William Henry Harrison broke the power of Tecumseh’s Indian confederation, set forward the hands of progress in the West a quarter of a century, and, incidentally, changed the map of Europe. A Missouri militia officer, Alexander Doniphan, without a war-chest, without supports, and without communications, invaded a hostile nation at the head of a thousand volunteers, repeatedly routed forces many times the strength of his own, conquered, subdued, and pacified a territory larger than France and Italy put together; and, after a march equivalent to a fourth of the circumference of the globe, returned to the United States, bringing with[ix] him battle-flags and cannon captured on fields whose names his country people had never so much as heard before. A missionary named Marcus Whitman, by the most daring and dramatic ride in history, during which he crossed the continent on horseback in the depths of winter, facing death almost every mile from cold, starvation, or Indians, prevented the Pacific Northwest from passing under the rule of England. Matthew Perry, without firing a shot or shedding a drop of blood, opened Japan to commerce, Christianity, and civilization, and made American influence predominant in the Pacific, though, a decade later, David McDougal was compelled to teach the yellow men respect for our citizens and our flag at the mouths of his belching guns.

Certain of these men have been accused of being adventurers, as they unquestionably were—but what, pray, were Hawkins and Raleigh and Drake? Others have been condemned as being filibusters, an accusation which in some cases was doubtless deserved—but were Jason and his Argonauts anything but filibusters who raided Colchis to loot it of the golden fleece? Adventurers and filibusters though some of them may have been, they were brave men (there can[x] be no disputing that) and makers of history. But it was their fortune—or misfortune—to have been romantic and picturesque and to have gone ahead without the formality of obtaining the government’s commission or permission, which, in the eyes of the sedate and prosaic historians, has completely damned them. But, as we have not hesitated to benefit from the lands they won for us, it is but doing them the barest justice to listen to their stories. And I think you will agree with me that in their stories there is remarkably little of which we need to feel ashamed and much of which we have reason to be proud.

Devious and dangerous were the roads which these men followed—amid the swamps of Florida, across the sun-baked Texan prairies, down the burning deserts of Chihuahua, over the snow-bound ridges of the Rockies, into the miasmic jungles of Tabasco, along the pirate-haunted coasts of Malaysia, across the Indian country, through the mined and shot-swept straits of Shimonoseki; but, no matter what perils bordered them, or into what far corner of the earth they led, at the end Glory beckoned and called.

E. Alexander Powell.

Santa Barbara,

California.

| PAGE | ||

| Foreword | vii | |

| I. | Adventurers All | 1 |

| II. | When We Smashed the Prophet’s Power | 55 |

| III. | The War That Wasn’t a War | 87 |

| IV. | The Fight at Qualla Battoo | 131 |

| V. | Under the Flag of the Lone Star | 161 |

| VI. | The Preacher Who Rode for an Empire | 195 |

| VII. | The March of the One Thousand | 235 |

| VIII. | When We Fought the Japanese | 277 |

| On the decks above were three hundred desperate and well-armed natives | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

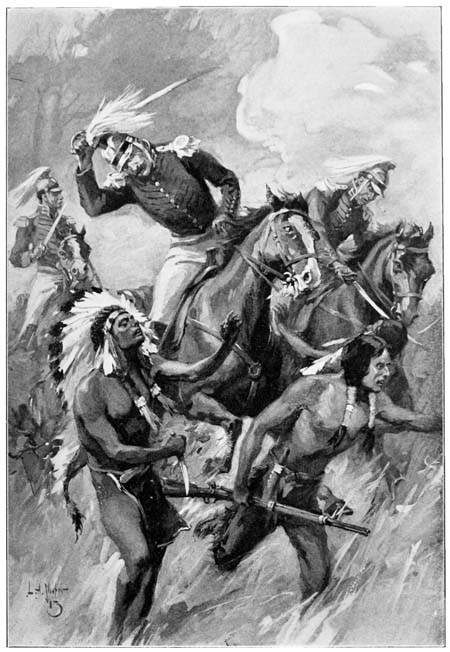

| The Indians, panic-stricken at the sight of the oncoming troopers, broke and ran | 84 |

| Bowie, propped on his pillows, shot two soldiers and plunged his terrible knife into the throat of another | 178 |

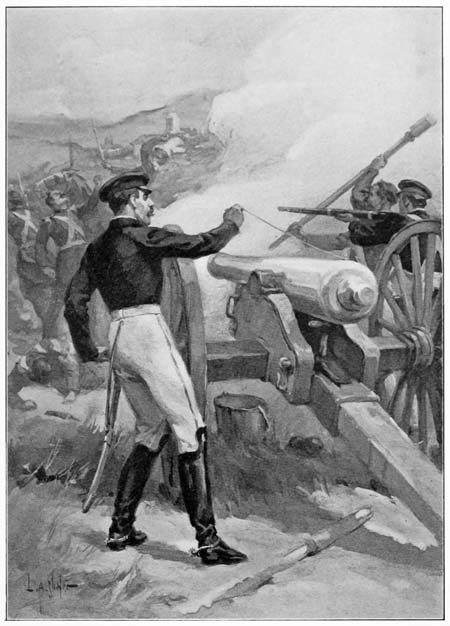

| In another moment the gun was pouring death into the ranks of its late owners | 260 |

[2]

ADVENTURERS ALL

THIS story properly begins in an emperor’s bathtub. The bathtub was in the Palace of the Tuileries, and, immersed to the chin in its cologne-scented water, was Napoleon. The nineteenth century was but a three-year-old; the month was April, and the trees in the Tuileries Garden were just bursting into bud; and the First Consul—he made himself Emperor a few weeks later—was taking his Sunday-morning bath. There was a scratch at the door—scratching having been substituted for knocking in the palace after the Egyptian campaign—and the Mameluke body-guard ushered into the bathroom Napoleon’s brothers Joseph and Lucien. How the conversation began between this remarkable trio of Corsicans is of small consequence. It is enough to know that Napoleon dumfounded his brothers by the blunt announcement that he had determined to sell the great colony of Louisiana—all that remained to France of her North American empire—to the United States. He made this astounding announcement, as Joseph wrote afterward,[4] “with as little ceremony as our dear father would have shown in selling a vineyard.” Incensed at Napoleon’s cool assumption that the great overseas possession was his to dispose of as he saw fit, Joseph, his hot Corsican blood getting the better of his discretion, leaned over the tub and shook his clinched fist in the face of his august brother.

“What you propose is unconstitutional!” he cried. “If you attempt to carry it out I swear that I will be the first to oppose you!”

White with passion at this unaccustomed opposition, Napoleon raised himself until half his body was out of the opaque and frothy water.

“You will have no chance to oppose me!” he screamed, beside himself with anger. “I conceived this scheme, I negotiated it, and I shall execute it. I will accept the responsibility for what I do. Bah! I scorn your opposition!” And he dropped back into the bath so suddenly that the resultant splash drenched the future King of Spain from head to foot. This extraordinary scene, which, ludicrous though it was, was to vitally affect the future of the United States, was brought to a sudden termination by the valet, who had been waiting with the bath towels, shocked at the spectacle of a future Emperor[5] and a future King quarrelling in a bathroom over the disposition of an empire, falling on the floor in a faint.

Though this narrative concerns itself, from beginning to end, with adventurers—if Bonaparte himself was not the very prince of adventurers, then I do not know the meaning of the word—it is necessary, for its proper understanding, to here interject a paragraph or two of contemporaneous history. In 1800 Napoleon, whose fertile brain was planning the re-establishment in America of that French colonial empire which a generation before had been destroyed by England, persuaded the King of Spain, by the bribe of a petty Italian principality, to cede Louisiana to the French. But in the next three years things turned out so contrary to his expectations that he was reluctantly compelled to abandon his scheme for colonial expansion and prepare for eventualities nearer home. The army he had sent to Haiti, and which he had intended to throw into Louisiana, had wasted away from disease and in battle with the blacks under the skilful leadership of L’Ouverture until but a pitiful skeleton remained. Meanwhile the attitude of England and Austria was steadily growing more hostile, and it did not need a telescope to see the war-clouds which heralded[6] another great European struggle piling up on France’s political horizon. Realizing that in the life-and-death struggle which was approaching he could not be hampered with the defense of a distant colony, Napoleon decided that, if he was unable to hold Louisiana, he would at least put it out of the reach of his arch-enemy, England, by selling it to the United States. It was a master-stroke of diplomacy. Moreover, he needed money—needed it badly, too—for France, impoverished by the years of warfare from which she had just emerged, was ill prepared to embark on another struggle.

There were in Paris at this time two Americans, Robert R. Livingston and James Monroe, who had been commissioned by President Jefferson to negotiate with the French Government for the purchase of the city of New Orleans and a small strip of territory adjacent to it, so that the settlers in Kentucky and Tennessee might have a free port on the gulf. After months spent in diplomatic intercourse, during which Talleyrand, the French foreign minister, could be induced neither to accept nor reject their proposals, the commissioners were about ready to abandon the business in despair. I doubt, therefore, if there were two more astonished men in all Europe than the[7] two Americans when Talleyrand abruptly asked them whether the United States would buy the whole of Louisiana and what price it would be willing to pay. It was as though a man had gone to buy a cow and the owner had suddenly offered him his whole farm. Though astounded and embarrassed, for they had been authorized to spend but two million dollars in the contemplated purchase, the Americans had the courage to shoulder the responsibility of making so tremendous a transaction, for there was no time to communicate with Washington and no one realized better than they did that Louisiana must be purchased at once if it was to be had at all. England and France were, as they knew, on the very brink of war, and they also knew that the first thing England would do when war was declared would be to seize Louisiana, in which case it would be lost to the United States forever. This necessity for prompt action permitted of but little haggling over terms, and on May 22, 1803, Napoleon signed the treaty which transferred the million square miles comprised in the colony of Louisiana to the United States for fifteen million dollars. Nor was the sale effected an instant too soon, for on that very day England declared war.

Now, in purchasing Louisiana, Jefferson, though[8] he got the greatest bargain in history, found that the French had thrown in a boundary dispute to give good measure. The treaty did not specify the limits of the colony.

“What are the boundaries of Louisiana?” Livingston asked Talleyrand when the treaty was being prepared.

“I don’t know,” was the answer. “You must take it as we received it from Spain.”

“But what did you receive?” persisted the American.

“I don’t know,” repeated the minister. “You are getting a noble bargain, monsieur, and you will doubtless make the best of it.”

As a matter of fact, Talleyrand was telling the literal truth (which must have been a novel experience for him): he did not know. The boundaries of Louisiana had never been definitely established. It seems, indeed, to have come under the application of

Hence, though American territory and Spanish marched side by side for twenty-five hundred miles, it was found impossible to agree on a[9] definite line of demarcation, the United States claiming that its new purchase extended as far westward as the Sabine River, while Spain emphatically asserted that the Mississippi formed the dividing line. Along about 1806, however, a working arrangement was agreed upon, whereby American troops were not to move west of the Red River, while Spanish soldiers were not to go east of the Sabine. For the next fifteen years this arrangement remained in force, the strip of territory between these two rivers, which was known as the neutral ground, quickly becoming a recognized place of refuge for fugitives from justice, bandits, desperadoes, adventurers, and bad men. To it, as though drawn by a magnet, flocked the adventure-hungry from every corner of the three Americas.

The vast territory beyond the Sabine, then known as New Spain and a few years later, when it had achieved its independence, as Mexico, was ruled from the distant City of Mexico in true Spanish style. Military rule held full sway; civil law was unknown. Foreigners without passports were imprisoned; trading across the Sabine was prohibited; the Spanish officials were suspicious of every one. Because this trade was forbidden was the very thing that made it so attractive[10] to the merchants of the frontier, while the grassy plains and fertile lowlands beyond the Sabine beckoned alluringly to the stock-raiser and the settler. And though there was just enough danger to attract them there was not enough strength to awe them. Jeering at governmental restrictions, Spanish and American alike, the frontiersmen began to pour across the Sabine into Texas in an ever-increasing stream. “Gone to Texas” was scrawled on the door of many a deserted cabin in Alabama, Tennessee, and Kentucky. “Go to Texas” became a slang phrase heard everywhere. On the western river steamboats the officers’ quarters on the hurricane-deck were called “the texas” because of their remoteness. When a boy wanted to coerce his family he threatened to run away to Texas. It was felt to be beyond the natural limits of the world, and the glamour which hovered over this mysterious and forbidden land lured to its conquest the most picturesque and hardy breed of men that ever foreran the columns of civilization. A contempt for the Spanish, a passion for adventure were the attitude of the people of our frontier as they strained impatiently against the Spanish boundaries. The American Government had nothing to do with winning Texas for the American people.[11] The American frontiersmen won Texas for themselves, unaided either by statesmen or by soldiers.

Though these men wrote with their swords some of the most thrilling chapters in our history, their very existence has been ignored by most of our historians. Though they performed deeds of valor of which any people would have reason to be proud, it was in an unofficial, shirt-sleeve sort of warfare, which the National Government neither authorized nor approved. Though they laid the foundations for adding an enormous territory to our national domain, no monuments or memorials have been erected to them; even their names hold no significance for their countrymen of the present generation. In short, they were filibusters, and that, in the eyes of those smug folk who believe that nothing can be meritorious that is done without the sanction of congresses and parliaments, completely damned them. They were American dreamers. Had they lived in the days of Cortes and Pizarro and Balboa, of Hawkins and Raleigh and Drake, history would have dealt more kindly with them.

The free-lance leaders, who, during the first quarter of the nineteenth century made the neutral ground a synonym for hair-raising adventure and desperate daring, were truly remarkable[12] men. Five of them had held commissions in the army of the United States; one of them had commanded the French army sent to Ireland; another was a peer of France and had led a division at Waterloo; others had won rank and distinction under Napoleon, Bolivar, and Jackson. But because they wore strange uniforms and fought under unfamiliar flags, and because, in some cases at least, they were actuated by motives more personal than patriotic, the historians have assumed that we do not want to know about them, or that it will be better for us not to know about them. They take it for granted that it is better for Americans to think that our territorial expansion was accomplished by men with government credentials in their pockets, and when these unofficial conquerors are mentioned they turn away their heads as though ashamed. But I believe that our people would prefer to know the truth about these men, and I believe that when they have heard it they will agree with me that in their amazing exploits there is much of which we have cause to be proud and surprisingly little of which we have need to feel ashamed.

The first of these adventurous spirits who for more than twenty years kept the Spanish and Mexican authorities in a fume of apprehension, was[13] a young Kentuckian named Philip Nolan. He was the first American explorer of Texas and the first man to publish a description of that region in the English language. He spent his boyhood in Frankfort, Kentucky, and as a young man turned up in New Orleans, then under Spanish rule, having been, apparently, a person of considerable importance in the little city. Having heard rumors that immense droves of mustangs roamed the plains of Texas and seeing for himself that the Spanish troopers in Louisiana were badly in need of horses, he told the Spanish governor that if he would agree to purchase the animals from him at a fixed price per head and would give him a permit for the purpose, he would organize an expedition to capture wild horses in Texas and bring them back to New Orleans. The governor, who liked the young Kentuckian, promptly signed the contract, gave the permit, and Nolan, with a handful of companions, crossed the Sabine into Texas, corralled his horses, brought them to New Orleans, and was paid for them. It was a profitable transaction for every one concerned. It was so successful that another year Nolan did it again. On the proceeds he went to Natchez, married the beauty of the town, and built a home. But along toward the close of[14] 1800 the governor wanted remounts again, for the Spanish cavalrymen seemed incapable of taking even ordinary care of their horses. So Nolan, who was, I fancy, already growing a trifle weary of the tameness of domestic life, enlisted the services of a score of frontiersmen as adventure-loving as himself, kissed his bride of a year good-by, and, after showing his passports to the American border patrol and satisfying them that his venture had the approval of the Spanish authorities, once more crossed the Sabine into Texas. For a proper understanding of what occurred it is necessary to explain that, though Louisiana was under the jurisdiction of the Spanish Foreign Office (for this was before the province had been ceded to France), Texas was under the control of the Spanish Colonial Office. Between these two branches of the government the bitterest jealousy existed, and a passport issued by one was as likely as not to be disregarded by the other. In fact, the colonial officials were only too glad of an opportunity to humiliate and embarrass those connected with the Foreign Office. But Nolan and his men, ignorant of this departmental jealousy and conscious that they were engaged in a perfectly innocent enterprise, went ahead with their business of capturing and breaking horses. Crossing the Trinity, they[15] found themselves on the edge of an immense rolling prairie which, as they advanced, became more and more arid and forbidding. There were no trees, not even underbrush, and the only fuel they could find was the dried dung of the buffalo. These animals, though once numerous, had disappeared, and for nine days the little company had to subsist on the flesh of mustangs. They eventually reached the banks of the Brazos, however, where they found plenty of elk and deer, some buffalo, and “wild horses by thousands.” Establishing a camp upon the present site of Waco, they built a stockade and captured and corralled three hundred head of horses. While lounging about the camp-fire one night, telling the stories and singing the songs of the frontier and thinking, no doubt, of the folks at home, a force of one hundred and fifty Spaniards, commanded by Don Nimesio Salcedo, commandant-general of the northeastern provinces, creeping up under cover of the darkness, succeeded in surrounding the unsuspecting Americans, who, warned of the proximity of strangers by the restlessness of their horses, retreated into a square enclosure of logs which they had built as a protection against an attack by Indians. At daybreak the Spaniards opened fire, and Nolan fell with a bullet through his brain. The command[16] of the expedition then devolved upon Ellis P. Bean, a boy of seventeen, who, from the scanty shelter of the log pen, continued a resistance that was hopeless from the first. Every one of the Americans was a dead shot and at fifty paces could hit a dollar held between a man’s fingers, but they were vastly outnumbered, they were unprovisioned for a siege, and, as a final discouragement, the Spaniards now brought up a swivel-gun and opened on them with grape. Bean urged his men to follow him in an attempt to capture this field-piece. “It’s nothing more than death, boys,” he told them, “and if we stay here we shall be killed anyway.” But his men were falling dead about him as he spoke, and the eleven left alive decided that their only chance, and that was slim enough, Heaven knows, lay in an immediate retreat. Filling their powder-horns and bullet pouches and loading the balance of their ammunition on the back of a negro slave named Cæsar, they started off across the prairie on their hopeless march, the Spaniards hanging to the flanks of the little party as wolves hang to the flank of a dying steer. All that day they plodded eastward under the broiling sun, bringing down with their unerring rifles those Spaniards who were incautious enough to venture within range. But at last they were[17] forced, by lack of food and water, to accept the offer of the Spanish commander to permit them to return to the United States unharmed if they would surrender and promise not to enter Texas again. No sooner had they given up their arms, however, than the Spaniards, afraid no longer, put their prisoners in irons and marched them off to San Antonio, where they were kept in prison for three months; then to San Luis Potosi, where they were confined for sixteen months more, eventually being forwarded, still in arms, to Chihuahua, where, in January, 1804, they were tried by a Spanish court, were defended by a Spanish lawyer, were acquitted, and the judge ordered their release. But Salcedo, who had become the governor of the province, determined that the hated gringos should not thus easily escape, countermanded the findings of the court, and forwarded the papers in the case to the King of Spain. The King, by a decree issued in February, 1807, after these innocent Americans had already been captives for nearly seven years, ordered that one out of every five of them should be hung, and the rest put at hard labor for ten years. But when the decree reached Chihuahua there were only nine prisoners left, two of them having died from the hardships to which they had been subjected. Under the circumstances[18] the judge, who was evidently a man of some compassion, construed the decree as meaning that only one of the remaining nine should be put to death.

On the morning of the 9th of November, 1807, a party of Spanish officials proceeded to the barracks where the Americans were confined and an officer read the King’s barbarous decree. A drum was brought, a tumbler and dice were set upon it, and around it, blindfolded, knelt the nine participants in this lottery of death. Some day, no doubt, when time has accorded these men the justice of perspective, Texas will commission a famous artist to paint the scene: the turquoise sky, the yellow sand, the sun glare on the whitewashed adobe of the barrack walls, the little, brown-skinned soldiers in their slovenly uniforms of soiled white linen, the Spanish officers, gorgeous in scarlet and gold lace, awed in spite of themselves by the solemnity of the occasion, and, kneeling in a circle about the drum, in their frayed and tattered buckskin, the prison pallor on their faces, the nine Americans—cool, composed, and unafraid.

| Ephraim Blackburn, a Virginian and the oldest of the prisoners, took the fatal [19]glass and with a hand which did not tremble—though I imagine that he whispered a little prayer—threw 3 and 1 | 4 |

| Lucian Garcia threw 3 and 4 | 7 |

| Joseph Reed threw 6 and 5 | 11 |

| David Fero threw 5 and 3 | 8 |

| Solomon Cooley threw 6 and 5 | 11 |

| Jonah Walters threw 6 and 1 | 7 |

| Charles Ring threw 4 and 3 | 7 |

| William Dawlin threw 4 and 2 | 6 |

| Ellis Bean threw 4 and 1 | 5 |

Whereupon they took poor Ephraim Blackburn out and hanged him.

After Blackburn’s execution three of the remaining prisoners were set at liberty, but Bean, with four of his companions, all heavily ironed, were started off under guard for Mexico City. Any one who questions the assertion that fact is stranger than fiction will change his mind after hearing of Bean’s subsequent adventures. They read like the wildest and most improbable of dime novels. When the prisoners reached Salamanca a young and strikingly beautiful woman, evidently attracted by Bean’s youth and magnificent physique, managed to approach him unobserved and asked him in a whisper if he did not wish to escape. (As if, after his years of captivity and hardship, he could have wished otherwise!)[20] Then she disappeared as silently and mysteriously as she had come. The next day the señora, who, as it proved, was the girl wife of a rich old husband, by bribing the guard, contrived to see Bean again. She told him quite frankly that her husband, whom she had been forced to marry against her will, was absent at his silver mines, and suggested that, if Bean would promise not to desert her, she would find means to effect his escape and that they could then fly together to the United States. It shows the manner of man this American adventurer was that, on the plea that he could not desert his companions in misfortune, he declined her offer. The next day, as the prisoners once again took up their weary march to the southward, the señora slipped into Bean’s hand a small package. When an opportunity came for him to open it he found that it contained a letter from his fair admirer, a gold ring, and a considerable sum of money.

Instead of being released upon their arrival at the city of Mexico, as they had been led to expect, the Americans were marched to Acapulco, on the Pacific, then a port of great importance because of its trade with the Philippines. Here Bean was placed in solitary confinement, the only human beings he saw for many months being the[21] jailer who brought him his scanty daily allowance of food and the sentry who paced up and down outside his cell. Had it not been for a white lizard which he found in his dungeon and which, with incredible patience, he succeeded in taming, he would have gone mad from the intolerable solitude. Learning from the sentinel that one of his companions had been taken ill and had been transferred to the hospital, Bean, who was a resourceful fellow, prepared his pulse by striking his elbows on the floor and then sent for the prison doctor. Though he was sent to the hospital, as he had anticipated, not only were his irons not removed but his legs were placed in stocks, and, on the theory that eating is not good for a sick man, his allowance of food was greatly reduced, his meat for a day consisting of the head of a chicken. When Bean remonstrated with the priest over the insufficient nourishment he was receiving, the padre told him that if he wasn’t satisfied with what he was getting he could go to the devil. Whereupon, his anger overpowering his judgment, Bean hurled his plate at the friar’s shaven head and laid it open. For this he was punished by having his head put in the stocks, in an immovable position, for fifteen days. When he recovered from the real fever which this barbarous[22] punishment brought on, he was only too glad to go back to the solitude of his cell and his friend the lizard.

While being taken back to prison, Bean, who had succeeded in concealing on his person the money which the señora in Salamanca had given him, suggested to his guards that they stop at a tavern and have something to drink. A Spaniard never refuses a drink, and they accepted. So skilfully did he ply them with liquor that one of them fell into a drunken stupor while the other became so befuddled that Bean found no difficulty in enticing him into the garden at the back of the tavern on the plea that he wished to show him a certain flower. As the man was bending over to examine the plant to which Bean had called his attention, the American leaped upon his back and choked him into unconsciousness. Heavily manacled though he was, Bean succeeded in clambering over the high wall and escaped to the woods outside the city, where he filed off his irons with the steel he used for striking fire. Concealing himself until nightfall, he slipped into the town again, where he found an English sailor who, upon hearing his pitiful story, smuggled him aboard his vessel and concealed him in a water-cask. But, just as the anchor was being hoisted[23] and he believed himself free at last, a party of Spanish soldiers boarded the vessel and hauled him out of his hiding-place—he had been betrayed by the Portuguese cook. For this attempt at escape he was sentenced to eighteen months more of solitary confinement.

One day, happening to overhear an officer speaking of having some rock blasted, Bean sent word to him that he was an expert at that business, whereupon he was taken out and put to work. Before he had been in the quarry a week he succeeded in once more making his escape. Travelling by night and hiding by day, he beat his way up the coast, only to be retaken some weeks later. When he was brought before the governor of Acapulco that official went into a paroxysm of rage at sight of the American whose iron will he had been unable to break either by imprisonment or torture. Bean, who had reached such a stage of desperation that he didn’t care what happened to him, looking the governor squarely in the eye, told him, in terms which seared and burned, exactly what he thought of him and defied him to do his worst. That official, at his wits’ end to know how to subdue the unruly American, gave orders that he was to be chained to a gigantic mulatto, the most dangerous criminal[24] in the prison, the latter being promised a year’s reduction in his sentence if he would take care of his yokemate, whom he was authorized to punish as frequently as he saw fit. But the punishing was the other way around, for Bean pommelled the big negro so terribly that the latter sent word to the governor that he would rather have his sentence increased than to be longer chained to the mad Americano. By this time Bean had every one in the castle, from the governor to the lowest warder, completely terrorized, for they recognized that he was desperate and would stop at nothing. He was, in fact, such a hard case that the governor of Acapulco wrote to the viceroy that he could do nothing with him and begged to be relieved of his dangerous prisoner. The latter, in reply, sent an order for his removal to the Spanish penal settlement in the Philippines. But while awaiting a vessel the revolt led by Morelos, the Mexican patriot, broke out, and a rebel army advanced on Acapulco. The prisons of New Spain had been emptied to obtain recruits to fill the Spanish ranks, and Bean was the only prisoner left in the citadel. The Spanish authorities, desperately in need of men, offered him his liberty if he would help to defend the town. Bean agreed, his irons were knocked off,[25] he was given a gun, and became a soldier. But he felt that he owed no loyalty to his Spanish captors; so, when an opportunity presented itself a few weeks later, he went over to Morelos, taking with him a number of the garrison. A born soldier, hard as nails, amazingly resourceful and brave to the point of rashness, he quickly won the confidence and friendship of the patriot leader, who commissioned him a colonel in the Republican army. When Morelos left Acapulco to continue his campaign in the south, he turned the command of the besieging forces over to the ex-convict, who, a few weeks later, carried the city by storm. It must have been a proud moment for the American adventurer, not yet thirty years of age, when he stood in the plaza of the captured city and received the sword of the governor who had treated him with such fiendish cruelty.[A]

[26]When the story of the treatment of Nolan and his companions trickled back to the settlements and was repeated from village to village and from house to house, every repetition served to fan the flame of hatred of everything Spanish, which grew fiercer and fiercer in the Southwest as the years rolled by. From the horror and indignation aroused along the frontier by the treatment of these men, whom the undiscerning historians have unjustly described as filibusters, sprang that movement which ended, a quarter of a century later, in freeing Texas forever from the cruelties of Latin rule. Thus it came about that Nolan and his companions did not suffer in vain.

Though during the years immediately following Nolan’s ill-fated expedition all Mexico was aflame with the revolt lighted by the patriot priest Hidalgo, things were fairly quiet along the border. But this was not to last. After the capture and execution of the militant priest one of his followers, Bernardo Gutierrez de Lara, after a thrilling flight across Texas, found refuge in Natchez, where he made the acquaintance of Lieutenant Augustus Magee, a brilliant young officer of the American garrison. Gutierrez painted pictures with words as an artist does with the brush, and so inspiring were the scenes his ready[27] tongue depicted that they fired the young lieutenant with an ambition to aid in freeing Mexico from Spanish rule. Magee was of a daring and romantic disposition and accepted without question the stories told him by Gutierrez. His plan seems to have been to conquer Texas to the Rio Grande and, after building up a republican state, to apply for admission to the Union. Resigning his commission, he threw himself heart and soul into the business of recruiting an expedition from the adventurers who made New Orleans—now become an American city—their headquarters and from the freebooters of the neutral ground. A call to these men to join the “Republican Army of the North” and receive forty dollars a month and a square league of land in Texas was eagerly responded to, and by June, 1812, Gutierrez and Magee had recruited half a thousand daredevils who, for the sake of adventure, were willing to follow their leaders anywhere. Most of them were “two-gun men,” which means that they went into action with a pistol in each hand and a knife between the teeth, and they didn’t know the name of fear. In order to secure the co-operation of the Mexican population of Texas, Gutierrez was named commander-in-chief of the expedition, though the real leader was Magee,[28] who held the position of chief of staff, an American frontiersman named Reuben Kemper being commissioned major.

In the beginning everything was as easy as falling down-stairs. The time chosen for the venture was peculiarly propitious, for the Spaniards had their hands full with the civil war in Mexico, which they supposed they had ended with the capture and execution of Hidalgo, but which had broken out again under the leadership of another priest, named Morelos. As a result of the demoralization which existed, the Americans were almost unopposed in their advance. Nacogdoches fell before them, and so did the fort at Spanish Bluff, and by November, 1812, they had raised the republican standard over La Bahia, or, as it is known to-day, Goliad. Three days later Governor Salcedo—the same who had attacked Nolan’s party a dozen years before—marched against the town with fourteen hundred men. Though the Americans were outnumbered more than two to one, they did not wait for the Spaniards to attack but sallied out and drove them back in confusion. Whereupon the Spaniards sat down without the town and prepared to conduct a siege, and the Americans sat down within and prepared to resist it. It ended in a peculiar fashion.[29] During a three days’ armistice Salcedo invited Magee to dine with him in the Spanish camp, and the American commander accepted. What arguments or inducements the astute Spaniard brought to bear on the young American can only be conjectured, but, at any rate, Magee agreed to surrender the town on condition that all of his men should be sent back to the United States in safety. To this condition Salcedo assented. Returning to the town, Magee had his men paraded, told them what he had done, and asked all who approved of his action to shoulder arms. For some moments after he had finished they stared at him in mingled amazement, incredulity, and suspicion. It was unbelievable, unthinkable, preposterous, that he, the idol of the army, the hero of a dozen engagements, a product of the great officer factory at West Point, should even contemplate, much less advocate, surrender. Not only did they not shoulder arms, but most of them, to emphasize their disapproval, brought their rifle butts crashing to the ground. For a few moments Magee stood with sunken head and downcast eyes; then he slowly turned and entered his tent. An hour or so later a messenger under a flag of truce brought a curt note from Salcedo reminding Magee of their agreement[30] and demanding to know why he had not surrendered the town as he had promised. The message was opened by Gutierrez, who ordered that no answer should be sent, whereupon Salcedo threw his entire force against the town in an attempt to carry it by storm. But the Americans, though sick at heart at the action of their young commander, were far from being demoralized, as the oncoming Spaniards quickly found, for as they reached the outer line of intrenchments the Americans met them with a blast of lead which wiped out their leading companies and sent the balance scampering San Antonio-ward. Throughout the action Magee remained hidden in his tent. When an orderly went to summon him the next morning he found the young West Pointer stretched upon the floor, with a pistol in his hand and the back blown out of his head.

Though Gutierrez still retained the nominal rank of general, the actual command of “the Army of the North” now devolved upon Major Reuben Kemper, a gigantic Virginian who, despite the fact that he was the son of a Baptist preacher, was celebrated from one end of the frontier to the other for his “eloquent profanity.” Kemper was a man well fitted to wield authority[31] on such an expedition. He had a neck like a bull, a chest like a barrel, a voice like a bass drum, and it was said that even the mates on the Mississippi River boats listened with admiration and envy to his swearing. Nor was he a novice at the business of fighting Spaniards, for a dozen years before he and his two brothers had been concerned in a desperate attempt to free Florida from Spanish rule; in 1808 he had been one of a party of Americans who had attempted to capture Baton Rouge, had been taken prisoner, sentenced to death, and saved by the intervention of an American officer on the very morning set for his execution; and the following year, undeterred by the narrowness of his escape, he had made a similar attempt, with similar unsuccess, to capture Mobile. The cruelties he had seen perpetrated by the Spaniards had so worked on his mind that he had vowed to devote the rest of his life to ridding North America of Spanish rule.

Such, then, was the picturesque figure who assumed command of “the Army of the North,” now consisting of eight hundred Americans, one hundred and eighty Mexicans, and three hundred and twenty-five Indians, and led it against the Spaniards, twenty-five hundred strong and with several pieces of artillery, who were encamped[32] at Rosales, near San Antonio. As soon as his scouts reported the proximity of the Spaniards, who were ambushed in the dense chaparral which lined the road along which the Americans were advancing, Kemper threw his force into battle formation, ordering his men to advance to within thirty paces of the Spanish line, fire three rounds, load the fourth time, and charge. The movement was performed in as perfect order as though the Americans had been on a parade-ground and no enemy within a hundred miles. Demoralized by the machine-like precision of the Americans’ advance and the deadliness of the volleys poured into them, the Spaniards broke and ran, Kemper’s Indian allies remorselessly pursuing the panic-stricken fugitives until nightfall put an end to the slaughter. In this great Texan battle, for any mention of which you will search most of the histories in vain, nearly a thousand Spaniards were killed and wounded. The Indians saw to it that there were few prisoners.

The next day the victorious Americans reached San Antonio and sent in a messenger, under a flag of truce, demanding the unconditional surrender of the town and garrison. Governor Salcedo sent back word that he would give his decision in the morning. “Present yourself and your[33] staff in our camp at once,” Kemper replied, “or I shall storm the town.” (And when a town was carried by storm it was understood that no prisoners would be taken.) When Salcedo entered the American lines he was met by Captain Taylor, to whom he offered his sword, but that officer declined to accept it and sent him to Colonel Kemper. On offering it to the big frontiersman, it was again refused, and he was told to take it to General Gutierrez, who was the ranking officer of the expedition. By this time the patience of the haughty Spaniard was exhausted, and, plunging the weapon into the ground, he turned his back on Gutierrez. A few hours later the Americans entered San Antonio in triumph, released the prisoners in the local jails, and, from all I can gather, took pretty much everything of value on which they could lay their hands. When Kemper asked his Indian allies what share of the loot they wanted, they replied that they would be quite satisfied with two dollars’ worth of vermilion.

After the capture of San Antonio, General Gutierrez, who, though he had been content to let the Americans do the fighting, now that he was among his own people swelled up like a turkey gobbler, announced that he had decided to send[34] the Spanish officers who had been captured to New Orleans, where they would be held as hostages until the war was over. To this suggestion the Americans readily agreed, and that evening the governor and his staff, with the other officers who had surrendered, started for the coast under the guard of a company of Mexicans. When a mile and a half below the town, on the east bank of the San Antonio River, the captives were halted, stripped, and tied, and their throats cut from ear to ear, some of the Mexicans even whetting their knives upon the soles of their shoes in the presence of their victims. When Kemper learned of this butchery of defenseless prisoners he strode up to Gutierrez and, catching him by the throat, held him at arm’s length and shook him as a terrier does a rat, meanwhile ripping out a stream of invectives that would have seared a thinner-skinned man as effectually as a branding-iron. Then, refusing to longer serve under so barbarous a leader, Kemper resigned his commission and, followed by most of the other American officers of standing, set out for New Orleans.

Of the American officers who remained Captain Perry was the highest in rank and the most able, and to him was given the direction of the expedition, Gutierrez, for reasons of policy, still[35] retaining nominal command. With the departure of Kemper came a relaxation in the iron discipline which he had maintained and the troops, drunk with victory and believing that the campaign was all over but the shouting, broke loose in every form of dissipation. While in this state of unpreparedness, they were surprised by a force of three thousand Spaniards under General Elisondo. Instead of marching directly upon San Antonio and capturing it, as he could have done in view of the demoralization which prevailed, Elisondo made the mistake of intrenching himself in the graveyard half a mile without the town. But in the face of the enemy the discipline for which the Americans were celebrated returned, for first, last, and all the time they were fighters. At ten o’clock on the evening of June 4 the Americans, marching in file, moved silently out of the town. In the most profound silence they approached the Spanish lines until they could hear the voices of the pickets; then they lay down, their arms beside them, and waited for the coming of the dawn. Colonel Perry chose the moment when the Spaniards were assembled at daybreak for matins to launch his attack. Even then no orders were spoken, the signals being passed down the line by each man nudging his[36] neighbor. So admirably executed were Perry’s orders that the Americans, moving forward with the stealth and silence of panthers, had reached the outer line of the enemy’s intrenchments, had bayonetted the Spanish sentries, and had actually hauled down the Spanish flag and replaced it with the Republican tricolor before their presence was discovered. Though taken completely by surprise, the Spaniards rallied and drove the Americans from the works, but the latter reformed and hurled themselves forward in a smashing charge which drove the Spaniards from the field, leaving upward of a thousand dead, wounded, and prisoners behind them. The American loss in killed and wounded was something under a hundred.

Returning in triumph to San Antonio, the Americans, whose position was now so firmly established that they had no further use for General Gutierrez, unceremoniously dismissed him, this action, doubtless, being taken at the instance of Colonel Perry and his fellow officers, who feared further treachery and dishonor if the Mexican were permitted to remain in command. His place was taken by Don José Alvarez Toledo, a distinguished Cuban who had formerly been a member of the Spanish Cortes in Mexico but had been[37] banished on account of his republican sympathies. A few weeks after General Toledo assumed command a Spanish force, four thousand strong, under General Arredondo, appeared before San Antonio. Toledo at once marched out to meet them. His force consisted of eight hundred and fifty Americans under Colonel Perry and about twice that number of Mexicans; so it will be seen that the Spaniards greatly outnumbered the Republicans. Throwing forward a line of skirmishers for the purpose of engaging the enemy, General Arredondo ambushed the major portion of his force behind earthworks masked by the dense chaparral. The Americans, confident of victory, dashed forward with their customary élan, whereupon the Spanish line, in obedience to Arredondo’s orders, sullenly fell back. So cleverly did the Spaniards feign retreat that it was not until the Americans were well within the trap that had been set for them that Toledo recognized his peril. Then he frantically ordered his buglers to sound the recall. One column—that composed of Mexicans—obeyed the order promptly, but the other, consisting of Americans, shouting, “No, we never retreat!” swept forward to their deaths. Had the order to retreat never been given, the Americans, notwithstanding the disparity of numbers, would[38] have been victorious, but, deprived of all support and raked by the enemy’s cannon and musketry, even the prodigies of valor they performed were unavailing to alter the result. So desperately did those American adventurers fight, however, that, as some one has remarked, “they made Spanish the language of hell.” When their rifles were empty they used their pistols, and when their pistols were empty they used their terrible long hunting-knives, ripping and stabbing and slashing with those vicious weapons until they went down before sheer weight of numbers. Some of them, grasping their empty rifles by the barrel, swung them round their heads like flails, beating down the Spaniards who opposed them until they were surrounded by heaps of men with cracked and shattered skulls. Others, when their weapons broke, sprang at their enemies with their naked hands and tore out their throats as hounds tear out the throat of a deer. Such was the battle of the Medina, fought on August 18, 1813. Of the eight hundred and fifty Americans who went into action only ninety-three came out alive. If the battle itself was a bloody one, its aftermath was even more so, the Spanish cavalry pursuing and butchering without mercy all the fugitives they could overtake. At Spanish Bluff, on the Trinity,[39] the Spaniards took eighty prisoners. Marching them into a clump of timber, they dug a long, deep trench and, setting the prisoners on its edge, shot them in groups of ten. It was a bloody, bloody business. That our histories contain almost no mention of the Gachupin War, as this campaign was known, is doubtless due to the fact that during the same period there was a war in the United States and also one in Mexico, and the public mind was thus drawn away from the events which were taking place in Texas. Indeed, had it not been for the war between the United States and Great Britain, which drew into its vortex the adventurous spirits of the Southwest, Texas would have achieved her independence a dozen years earlier than she did.

Toledo and Perry, with all that was left of the “Army of the North,” escaped, after suffering fearful hardships, to the United States, where they promptly began to recruit men for another venture into the beckoning land beyond the Sabine. Though the head of the patriot priest Hidalgo had been displayed by the Spanish authorities on the walls of the citadel of Guanajuato as “a warning to Mexicans who choose to revolt against Spanish rule,” as the placard attached to the grisly trophy read, the grim object-lesson had not[40] deterred another priest, José Maria Morelos, from taking up the struggle for Mexican independence where Hidalgo had laid it down. In order to co-operate with this new champion of liberty, Toledo, at the head of a few hundred Americans, sailed from New Orleans, landed on the Mexican coast near Vera Cruz, and pushed up-country as far as El Puente del Rey, near Jalapa, where he intrenched himself and sat down to await the arrival of reinforcements from New Orleans under General Jean Joseph Humbert.

Humbert, a Frenchman from the province of Lorraine, was a graduate of the greatest school for fighters the world has ever known: the armies of Napoleon. In 1789, when the French Revolution deluged France with blood, he was a merchant in Rouvray. Closing his shop, he exchanged his yardstick for a sabre and went to Paris to take a hand in the overthrow of the monarchy, for he was a red-hot republican. His gallantry in action won him a major-general’s commission, and four years later the Directory promoted him to the rank of lieutenant-general and gave him command of the expedition sent to Ireland, where he was forced to surrender to Lord Cornwallis. Napoleon, who knew a soldier as far as he could see one, made Humbert a general[41] of division and second in command of the ill-fated army sent to Haiti. But Humbert’s republican convictions did not jibe with the imperialistic ambitions of Napoleon, and the former suddenly decided that a life of exile in America was preferable to life in a French prison. For a time he supported himself by teaching in New Orleans, but it was like harnessing a war-horse to a plough; so, when the Mexican junta sought his aid in 1814, the veteran fighter raised an expeditionary force of nearly a thousand men, sailed across the Gulf, landed on the shores of Mexico, and marched up to join Toledo at El Puente del Rey. The revolutionary leader Morelos, who was hard-pressed by the Spaniards, set out to join Toledo and Humbert, but on the way was taken prisoner and died with his back to a stone wall and his face to a firing-party. The same force which ended the career of Morelos continued to El Puente del Rey and attempted to cut off the retreat of Toledo and Humbert, but the old soldier of Napoleon succeeded in cutting his way through them and in 1817, dejected and discouraged, landed once more at New Orleans, where he spent the rest of his days teaching in a French college, and his nights, no doubt, dreaming of his exploits under the Napoleonic eagles.

[42]The same year Humbert returned to New Orleans another soldier of the empire, General Baron Charles François Antoine Lallemand, followed by a hundred and fifty veterans who had seen service under the little corporal, set out from the same city for that graveyard of ambitions, Mexico. Baron Lallemand was one of the great soldiers of the empire and, had Napoleon been victorious at Waterloo, would have been rewarded with the baton of a marshal of France. Entering the army when a youngster of eighteen, he followed the French eagles into every capital of Europe, fighting his way up the ladder of promotion, round by round, until, upon the Emperor’s return from Elba, he was given the epaulets of a lieutenant-general and created a peer of France. He commanded the artillery of the Imperial Guard at Waterloo and after that disaster was sent by the Emperor to Captain Maitland, of the British navy, to negotiate for his surrender. With tears streaming down his cheeks, Lallemand begged that he might be permitted to accompany his imperial master into exile. This being denied him, he refused to take service under the Bourbons and, coming to America, attempted to found a colony of French political refugees in Alabama, at a place which, in memory of happier days, he[43] named Marengo. The experiment proved a failure, however; so in 1817 he led his colonists into Texas and attempted to establish what he termed a Champ d’Asile on the banks of the Trinity River. But the Spanish authorities, obsessed with the idea that every foreigner who appeared in Texas was plotting against them, despatched a force against Lallemand and his colonists and drove them out. The next few years General Lallemand spent in New Orleans devising schemes for effecting the escape of his beloved Emperor from St. Helena, but Napoleon’s death, in 1821, brought his carefully laid plan for a rescue to naught. In 1830, upon the Bourbons being ejected from France for good and all, Lallemand, to whom the Emperor had left a legacy of a hundred thousand francs, returned to Paris. His civil and military honors were restored by Louis Philippe, and the man who a few years before had been pointed out on the streets of New Orleans as a filibuster and an adventurer died a general of division, commander of the Legion of Honor, military governor of Corsica, and a peer of France.

The next man to strike a blow for Texas was Don Luis de Aury. De Aury was a native of New Granada, as the present Republic of Colombia was[44] then called, and had played a brilliant part in the struggle for freedom of Spain’s South American colonies. He entered the navy of the young republic as a lieutenant in 1813. Three years later he was appointed commandant-general of the naval forces of New Granada, stationed at Cartagena. At the memorable siege of that city, to his generosity and intrepidity hundreds of men, women, and children owed their lives, for when the Spanish commander, Morillo, threatened to butcher every person found alive within the city walls De Aury loaded the non-combatants aboard his three small vessels, broke through the Spanish squadron of thirty-five ships and landed his passengers in safety. For this heroic exploit he was rewarded with the rank of commodore, given the command of the united fleets of New Granada, La Plata, Venezuela, and Mexico, and ordered to sweep Spanish commerce from the Gulf. Learning of the splendid harbor afforded by the Bay of Galveston, on the coast of Texas, he determined to occupy it and use it as a base of operations against the Spanish. Accompanied by Don José Herrera, the agent of the Mexican revolutionists in the United States, De Aury landed on Galveston Island in September, 1816. A meeting was held, a government organized, the Republican flag raised,[45] Galveston was declared a part of the Mexican Republic, and De Aury was chosen civil and military governor of Texas and Galveston Island.

Here he was shortly joined by two other adventurers: our old friend, Colonel Perry, who had escaped to the United States after the disaster of the Medina, and Francisco Xavier Mina, a soldier of fortune from Navarre. Mina’s parents, who were peasant farmers, had destined him for the law, but when Napoleon invaded Spain, young Mina threw away his law books, raised a band of guerillas, and harassed the invaders until his name became a terror to the French. He was captured in 1812 and, after several years in a French prison, went to England, where he made the acquaintance of a number of Mexican political exiles, who induced him to take a hand in freeing their native country. In September, 1816, Mina’s expedition, consisting of two hundred infantry and a battery of artillery, sailed from Baltimore for Galveston, where he found De Aury with some four hundred well-drilled men and Colonel Perry with a hundred more. In March, 1817, the three commanders sailed for the mouth of the Rio Santander, fifty miles up the Mexican coast from Tampico, and disembarked their forces at the river bar. The town of Soto la Marina, sixty[46] miles from the river’s mouth, fell without opposition, and with its fall the leaders parted company. De Aury returned to Galveston, but, finding the pirate Lafitte in possession, sailed away in search of pastures new. Mina, ambitious for further conquests, marched into the interior, capturing Valle de Mais, Peotillos, Real de Rinos, and Venadito in rapid succession. At Venadito, however, his streak of good fortune ended as suddenly as it had begun, for while his men were scattered in search of plunder a Spanish force recaptured the town and made Mina a prisoner. So relieved was the Spanish Government at receiving word of his capture and execution that it ordered the church-bells to be rung in every town in Mexico and made the viceroy a count.

When Colonel Perry learned of Mina’s plan for marching into the interior with the small force at his disposal, he flatly refused to have anything to do with so harebrained a business and, with fifty of his men, started up the coast in an attempt to make his way back to the United States. As the disastrous retreat began in May, when water was scarce and the heat in the swampy lowlands was almost unbearable, they suffered terribly. Just as the little band of adventurers reached the borders of Texas and were congratulating themselves[47] on having all but won to safety, a party of two hundred Spanish cavalry suddenly appeared. Perry, throwing his men into line of battle, received the onslaught of the lancers with a volley which checked them in mid-career and would doubtless have ended the contest then and there had not the garrison of the near-by town sallied out and taken the Americans in the rear. Clothed in rags, scorched by the sun, parched from thirst, half starved, surrounded by an overwhelming foe, gallantly did these desperate men sustain their reputation for valor. Again and again the lancers swept down upon them, again and again the garrison attacked them in the rear, but always from the thinning line of heroes spat a storm of lead so deadly that the Spaniards could not stand before it. Blackened with smoke and powder, fainting from hunger and exhaustion, bleeding from innumerable wounds, the adventurers fought like men who welcomed death. The sun had disappeared; the shadows of night were gathering thick upon the plain; but still a handful of powder-grimed, blood-streaked men, standing back to back, amid a ring of dead and dying, held off the enemy. As the darkness deepened, a single gallant figure still waved a defiant sword: it was Perry, who, true to the filibusters’ motto[48] that “Americans never surrender,” fell by his own hand.

Probably the most remarkable of this long list of adventurers was the Jean Lafitte whom De Aury found in possession of Galveston. A Frenchman by birth and an American by adoption, he and his brother Pierre had, during the early years of the century, established on Barataria Island, near the mouth of the Mississippi, what was virtually a pirate kingdom, where they drove a thriving trade with the planters along the upper river and the merchants of New Orleans in smuggled slaves and merchandise. Although both the State and federal authorities had made repeated attempts to dislodge them, the Lafittes were at the height of their prosperity when the second war with England began. When the British armada destined for the conquest of Louisiana arrived off the Mississippi, late in 1814, an officer was sent to Jean Lafitte offering him fifty thousand dollars and a captain’s commission in the royal navy if he would co-operate with the British in the capture of New Orleans. Though Governor Claiborne, of Louisiana, had set a price on his head, Lafitte, who was, it seemed, a patriot first and a pirate afterward, hastened up the river to New Orleans, warned the governor of the[49] approach of the British fleet, and offered his services and those of his men to Andrew Jackson for the defense of the city. His offer was accepted in the spirit in which it was made, and Lafitte and his red-shirted buccaneers played no small part in winning the famous victory. They were mentioned in despatches by Jackson, thanked for their services by the President and pardoned, and settled down for a time to a lawful and humdrum existence. But for such men a life of ease and safety held no attractions; so, about the time that De Aury’s squadron sailed for Soto la Marina, Lafitte, with half a dozen vessels, dropped casually into the harbor of Galveston and, as the place suited him, coolly took possession.

By the close of 1817 the followers of Lafitte on Galveston Island had increased to upward of a thousand men. They were of all nations and all languages—fugitives from justice and fugitives from oppression. Those of them who had wives brought them to the settlement at Galveston, and those who had no wives brought their mistresses, so that the society of the place, whatever may be said of its morals, began to assume an air of permanency. On the site of the hut occupied by the late governor, De Aury, Lafitte erected a pretentious house and built a fort; other buildings[50] sprang up, among them a “Yankee” boarding-house, and, to complete the establishment, a small arsenal and dockyard were constructed. To lend an air of respectability to his enterprise, Lafitte obtained privateering commissions from several of the revolted colonies of Spain, and for several years his cruisers, first under one flag and then under another, conducted operations in the Gulf which smacked considerably more of piracy than of privateering. In 1819 Lafitte was taken into the service of the Republican party in Mexico, Galveston was officially made a port of entry, and he was appointed governor of the island.

By the terms of the treaty whereby Spain, in 1819, sold Florida to the United States, the latter agreed to accept the Sabine as its western boundary and make no further claims to Texas. Though this treaty aroused the most profound indignation throughout the Southwest, nowhere did it rise so high as in the town of Natchez. From Natchez had gone out each of the expeditions which, since the days of Philip Nolan, had hammered against the Spanish barriers. To it had returned every leader who had escaped death on the battle-field or before a firing-party. In it, as a great river town enjoying a vast trade with the interior, was gathered the most reckless, lawless,[51] enterprising population—flatboatmen, steamboatmen, frontiersmen—to be found in all the Southwest. So, when Doctor James Long, an army surgeon who had served under Jackson at New Orleans, called for recruits to make one more attempt to free Texas, he did not call in vain. Early in June Long set out from Natchez with only seventy-five men, but no sooner had he crossed the Sabine and entered Texas than the survivors of former expeditions hastened to join him, so that when Nacogdoches was reached he had behind him upward of three hundred men: veterans who had seen service under Nolan and Magee, and Kemper, and Gutierrez, and Toledo, and Humbert, and Perry, and Mina, and De Aury. At Nacogdoches Long established a provisional government, a supreme council was elected, and Texas was proclaimed a free and independent republic. Realizing, however, that he could not hope to hold the territory thus easily occupied for any length of time unaided, Long despatched a commission to Galveston to ask the co-operation of Lafitte. Though the pirate chieftain received the commissioners with marked courtesy and entertained them at the “Red House,” as his residence was called, with the lavish hospitality for which he was noted, he told them bluntly[52] that, though Doctor Long had his best wishes for success, the fate of Nolan and Perry and Mina and a host of others ought to convince him how hopeless it was to wage war against Spain with so insignificant a force. Upon receiving this answer, Doctor Long, believing that a personal application to the buccaneer might meet with better success, himself set out for Galveston. As luck would have it, he reached there on the same day that the American war-ship Enterprise dropped anchor in the harbor and its commander, Lieutenant Kearny, informed Lafitte that he had imperative orders from Washington to break up the establishment at Galveston. There was nothing left for Lafitte but to obey, and a few days later the rising tide carried outside Galveston bar the Pride and the other vessels comprising the fleet of the last of the buccaneers, who abandoned the shores of Texas forever.[B]

Doctor Long, thoroughly discouraged, returned to Nacogdoches to find a Spanish army close at hand and his own forces completely demoralized. Surrounded and outnumbered, resistance was useless and he surrendered. Though Spanish dominion[53] in Mexico was now at an end, Doctor Long and a number of his companions were sent to the capital, where for several months he was held a prisoner, the vigorous representations of the American minister finally resulting in his release. The Mexicans had no more intention than the Spaniards, however, of permitting Texas to achieve independence, which, doubtless, accounts for the fact that Doctor Long, who was known as a champion of Texan liberty, was assassinated by a soldier in the streets of the capital a few days after his release from prison. But he and the long line of adventurers who preceded him did not fight and die in vain, for they paved the way for the Austins and Sam Houston, the final liberators of Texas, who, a few years later, crossed the Sabine and completed the work that Nolan, Magee, Kemper, Gutierrez, Toledo, Humbert, Perry, Mina, De Aury, and Long had begun. As for Lafitte, the most picturesque adventurer of them all, he sailed away from Galveston and, following the example of that long line of buccaneers of whom he was the last, spent his latter years in harrying the commerce of the Dons upon the Spanish main. Along the palm-fringed Gulf coast his memory still survives, and at night the superstitious sailors sometimes claim to see the[54] ghostly spars of his rakish craft and to hear, borne by the night breeze, the rumble of his distant cannonading.

[56]

WHEN WE SMASHED THE PROPHET’S POWER

IT is a curious and interesting fact that, just as in the year 1754 a collision between French and English scouting parties on the banks of the Youghiogheny River, deep in the American wilderness, began a war that changed the map of Europe, so in 1811 a battle on the banks of the Wabash between Americans and Indians started an avalanche which ended by crushing Napoleon.

The nineteenth century was still in its swaddling-clothes at the time this story opens; the war of the Revolution had been over barely a quarter of a century, and a second war with England was shortly to begin. Though the borders of the United States nominally extended to the Rockies, the banks of the Mississippi really marked the outermost picket-line of civilization. Beyond that lay a vast and virgin wilderness, inconceivably rich in minerals, game, and timber, but still in the power of more or less hostile tribes of Indians. Up to 1800 the whole of that region lying beyond the Ohio, including the present States of Indiana,[58] Illinois, Wisconsin, Michigan, Iowa, and Missouri, was officially designated as the Northwest Territory, but in that year the northern half of this region was organized as the Indian Territory, or, as it came to be known in time, the Territory of Indiana.

The governor of this great province was a young man named William Henry Harrison. This youth—he was only twenty-seven at the time of his appointment—was invested with one of the most extraordinary commissions ever issued by our government. In addition to being the governor of a Territory whose area was greater than that of the German Empire, he was commander-in-chief of the Territorial militia, Indian agent, land commissioner, and sole lawgiver. He had the power to adopt from the statutes upon the books of any of the States any and every law which he deemed applicable to the needs of the Territory. He appointed all the judges and other civil officials and all military officers below the rank of general. He possessed and exercised the authority to divide the Territory into counties and townships. He held the prerogative of pardon. His decision as to the validity of existing land grants, many of which were technically worthless, was final, and his signature[59] upon a title was a remedy for all defects. As the representative of the United States in its relations with the Indians, he held the power to negotiate treaties and to make treaty payments.

Governor Harrison was admittedly the highest authority on the northwestern Indians. He kept his fingers constantly on the pulse of Indian sentiment and opinion and often said that he could forecast by the conduct of his Indians, as a mariner forecasts the weather by the aid of a barometer, the chances of war and peace for the United States so far as they were controlled by the cabinet in London. The remark, though curious, was not surprising. Uneasiness would naturally be greatest in regions where the greatest irritation existed and which were under the least control. Such a danger spot was the Territory of Indiana. It occupied a remote and perilous position, for northward and westward the Indian country stretched to the Great Lakes and the Mississippi, unbroken save by the military posts at Fort Wayne and Fort Dearborn (now Chicago) and a considerable settlement of whites in the vicinity of Detroit. Some five thousand Indian warriors held this vast region and were abundantly able to expel every white man from Indiana if their[60] organization had been as strong as their numbers. And the whites were no less eager to expel the Indians.

No acid ever ate more resistlessly into a vegetable substance than the white man acted on the Indian. As the line of American settlements approached the nearest Indian tribes shrunk and withered away. The most serious of the evils which attended the contact of the two hostile races was the introduction by the whites of whiskey among the Indians. “I can tell at once,” wrote Harrison about this time, “upon looking at an Indian whom I may chance to meet, whether he belongs to a neighboring or a more distant tribe. The latter is generally well-clothed, healthy, and vigorous; the former half-naked, filthy, and enfeebled by intoxication.” Another cause of Indian resentment was that the white man, though not permitted to settle beyond the Indian border, could not be prevented from trespassing far and wide on Indian territory in quest of game. This practice of hunting on Indian lands in direct violation of law and of existing treaties had, indeed, grown into a monstrous abuse and did more than anything else, perhaps, to fan the flame of Indian hostility toward the whites. Every autumn great numbers of Kentucky settlers used to cross[61] the Ohio River into the Indian country to hunt deer, bear, and buffalo for their skins, which they had no more right to take than they had to cross the Alleghanies and shoot the cows and sheep belonging to the Pennsylvania farmers. As a result of this systematic slaughter of the game, many parts of the Northwest Territory became worthless to the Indians as hunting-grounds, and the tribes that owned them were forced either to sell them to the government for supplies or for an annuity or to remove elsewhere. The Indians had still another cause for complaint. According to the terms of the treaties, if an Indian killed a white man the tribe was bound to surrender the murderer for trial in an American court; while, if a white man killed an Indian, the murderer was also to be tried by a white jury. The Indians surrendered their murderers, and the white juries at Vincennes unhesitatingly hung them; but, though Harrison reported innumerable cases of wanton and atrocious murders of Indians by white men, no white man was ever convicted by a territorial jury for these crimes. So far as the white man was concerned, it was a case of “Heads I win, tails you lose.” The opinion that prevailed along the frontier was expressed in the frequent assertion that “the only good Indian is[62] a dead one,” and in the face of such public opinion there was no chance of the Indian getting a square deal.

As a result of these outrages and injustices, the thoughts of the Indians turned longingly toward the days when this region was held by France. Had Napoleon carried out his Louisiana scheme of 1802, there is no possible doubt that he would have received the active support of every Indian tribe from the Gulf to the Great Lakes; his orders would have been obeyed from Tallahassee to Detroit. When affairs in Europe compelled him to abandon his contemplated American campaign, the Indians turned to the British for sympathy and assistance—and the British were only too glad to extend them a friendly hand. From Maiden, opposite Detroit, the British traders loaded the American Indians with gifts and weapons; the governor-general of Canada intrigued with the more powerful chieftains and assured himself of their support in the war which was approaching; British emissaries circulated among the tribes, and by specious arguments inflamed their hostility toward Americans. Indeed, it is no exaggeration to say that, had our people and our government treated the Indians with the most elementary justice and honesty, they would have[63] had their support in the War of 1812, the whole course of that disastrous war would probably have been changed, and the Canadian boundary would, in all likelihood, have been pushed far to the northward. By their persistent ill treatment of the Indians the Americans received what they had every reason to expect and what they fully deserved.

During the first decade of the nineteenth century there was really no perfect peace with any of the Indian tribes west of the Ohio, and Harrison’s abilities as a soldier and a diplomatist were taxed to the utmost to prevent the skirmish-line, as the chain of settlements and trading-posts which marked our westernmost frontier might well be called, from being turned into a battle-ground. Harrison’s most formidable opponent in his task of civilizing the West was the Shawnee chieftain Tecumseh, perhaps the most remarkable of American Indians. Though not a chieftain by birth, Tecumseh had risen by the strength of his personality and his powers as an orator to a position of altogether extraordinary influence and power among his people. So great was his reputation for bravery in battle and wisdom in council that by 1809 he had attained the unique distinction of being, to all intents and purposes, the[64] political leader of all the Indians between the Ohio and the Mississippi.

With the vision of a prophet, Tecumseh saw that if this immense territory was once opened to settlement by whites the game upon which the Indians had to depend for sustenance must soon be exterminated and that in a few years his people would have to move to strange and distant hunting-grounds. Taking this as his text, he preached a gospel of armed resistance to the white man’s encroachments at every tribal council-fire from the land of the Chippewas to the country of the Creeks. And he had good reasons for his warnings, for the Indians were being stripped of their lands in shameless fashion. In fact, the Indian agents were deliberately ordered to tempt the tribal chiefs into debt in order to oblige them to sell the tribal lands, which did not belong to them, but to their tribes. The callousness of the government’s Indian policy was frankly expressed by President Jefferson in a letter to Harrison in 1803: