Hyphenations have been standardised.

Footnotes have been renamed in numeric order.

Changes made are noted at the end of the book.

The advertisement which was at the front of the book has been placed at the end.

[ii]

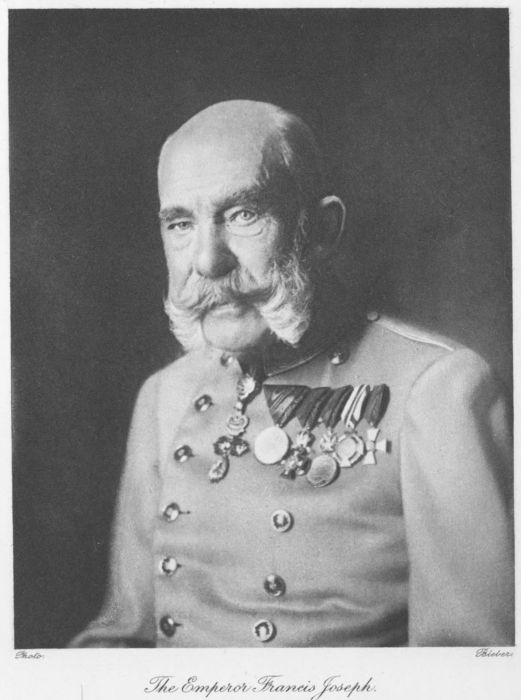

Photo Bieber

THE EMPEROR FRANCIS JOSEPH

[iv]THE LIFE OF THE EMPEROR FRANCIS JOSEPH

BY

FRANCIS GRIBBLE

LONDON EVELEIGH NASH

1914

[v]

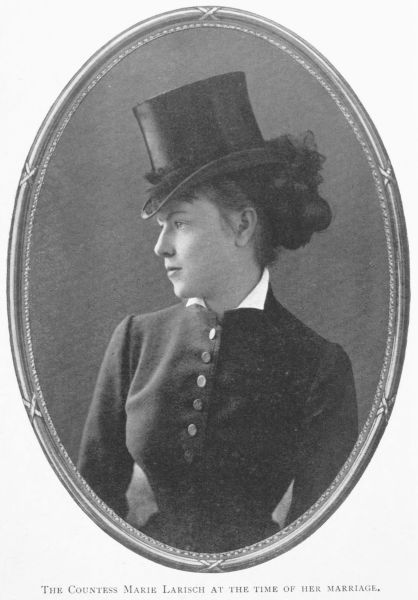

There exist plenty of surveys of the modern history and political conditions of Austria. Mr. Henry Wickham Steed’s “The Habsburg Monarchy” is the most recent, and probably the best, though Mr. R. P. Mahaffy’s “Francis Joseph I.: His Life and Times”—a smaller and less pretentious book—is also very good. One knows equally well where to turn for gossipy compilations—some of them authoritative, and others devoid of authority—dealing with the inner life of the Austrian Court. Sir Horace Rumbold has treated the subject with the dutiful reticence of a diplomatist in “The Austrian Court of the Nineteenth Century”; Countess Marie Larisch and Princess Louisa of Tuscany, occupying positions of greater freedom and less responsibility, have in “My Past” and “My Own Story” lifted the veil with indignant gestures, and pointed fingers of scorn at the intimate pictures which they have revealed. M. H. de Weindel, again, has written of “François-Joseph Intime”; while the enterprise of an American journalist has contributed “The Keystone of Empire,” “The Martyrdom of[vi] an Empress,” and “The Private Life of Two Emperors—William II. of Germany and Francis Joseph of Austria.”

This bibliographical list—to which additions could easily be made—might seem to indicate that the ground has already been well covered; but that is not the case. There exists no life of Francis Joseph, and no History of Austria, in which the personal and political aspects of the subject are considered in their relation to each other. The assumption of writers who have previously treated the theme has been that tittle-tattle is tittle-tattle, and that history is history, and that the two can never meet. The two things, however, are liable to meet anywhere; and in the country and period here under review they are continually meeting. Austria is not one of the “inevitable” countries, like England and Spain, bound to have a separate existence under some form of government or other because of their geographical situation and the national characteristics of their inhabitants. There is no Austrian nation: only a medley of races which detest each other, bound (but by no means welded) together for the supposed convenience of the rest of Europe, and unified only by the fact that its component parts all appertain to the dominions of the House of Habsburg.

It follows that the personality of the Habsburgs matters in a sense in which the personalities of rulers who are mere figure-heads does not matter; and that personality—the collective personality as well as the separate personalities of individual[vii] members of the House—can only be gauged by those who study their private lives in conjunction with their public performances. The history of the property (seeing that it comprises peoples as well as lands) includes and implies the history of the owners of the property. Our spectacle, in so far as one can sum it up in a sentence, is that of an Empire continually threatened with dissolution under the control of an historic family continually displaying all the symptoms of decadence. The political and the personal factors in the problem are perpetually interacting; and one of the questions which the political prophet has to consider is: Will not the decadence of the family hasten the dissolution of the Empire?

Whence it follows, as a secondary sequence, that, in the history of modern Austria, tittle-tattle matters; for it is only by the careful study of the tittle-tattle that we can hope to discover whether the Habsburgs of to-day are true or false to the proud and impressive traditions of their House. In their case, as in that of any other House, a stray story of a romantic or scandalous character might properly be ignored as appertaining to the domain of idle gossip; but when stories of that kind meet us at every turn—and meet us with increasing frequency as time proceeds—we are no longer entitled to dismiss them with superior indifference. They are significant; the key to the situation is to be found in them. Tittle-tattle, in short, when one encounters it, not in sample but in bulk, ceases to be tittle-tattle, but attains to the dignity of history, and[viii] furnishes the raw material for the generalisations of the political philosopher.

The annals of the House of Habsburg furnish a case in point—the best of all possible cases. There is no House in Europe whose annals are richer in incident and eccentricity; and the eccentricities, whether romantic or scandalous, are such as to challenge the scientific investigator—whether he be a student of eugenics or of politics—to group them and see what inferences he can draw. The present writer has decided to take up the challenge; and, in order to take it up, he will be obliged to deal with a good many matters besides the political manœuvres of the Emperor and his Ministers. “John Orth” pelting the Emperor with the insignia of the Order of the Golden Fleece; “Herr Wulfling” cracking nuts in a tree with Fräulein Adamovics; Princess Louisa of Tuscany, first bicycling with the dentist in the Dresden Park, and then appealing to her son’s tutor to come and “compromise” her in Switzerland—all these are matters which may suggest reflections quite as far-reaching as anything that we read about Francis Joseph’s skill in extricating his country from embarrassments with rival Powers and keeping the peace (in so far as it has been kept) between Ruthenians and Galicians.

It would be presumption, of course, to represent this biography as the full and final portrait of Francis Joseph as he really is. The complete material for such a definite portrait of a sovereign is never made available during the sovereign’s life-time; and the portraits drawn by people who have[ix] occupied privileged positions at Court are generally the most colourless of all: misleading—and, as a rule, designed to mislead—by excess of eulogy. Discretion, in such cases, takes the place of criticism; the “selection” is not that of the artist, but of the courtier. The illustrious personage thus officially or semi-officially portrayed “comes out” not as an individual, but as a type: as conventional and as unconvincing as the stock “heavy father” or “gentlemanly villain” of melodrama. Sir Horace Rumbold’s polite portrait of Francis Joseph is one of many marked by those limitations. The popular Austrian portraits are still more distinctly marked by them.

One need not wonder, and one must not complain. The path to candour was blocked by the obligations, in the one case of hospitality, and, in the other, of loyalty; but there is no reason why the historian who is not under such obligations should not criticise more freely. His object is neither depreciation nor flattery, but truth—as much of the truth as is attainable at the given moment; and he must therefore resist the common tendency of the biographers of contemporary rulers to credit their subjects, not only with their own particular virtues, but with all other people’s virtues as well. The only result, in moral portraiture, of attributing virtues with too heavy a hand is to produce a picture in which the wood cannot be seen for the trees.

That error must be avoided, as much in the interest of the subject of the portrait as in that of the public to which it is to be submitted. The real[x] virtues will be more conspicuous if no imaginary virtues are allowed to block our view of them, and if other miscellaneous qualities which contrast with them are given their due tribute of attention. Cromwell, it will be remembered, insisted that the artist should paint him “warts and all,”; and if the Life of an Emperor is not to be written in that spirit, one might just as well refrain from writing it, for there would be nothing to be learnt from it when it was written.

FRANCIS GRIBBLE.

[xi]

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Chapter I | |

| The collapse of the Holy Roman Empire—The impossibility of reviving it—The German Federation—The Holy Alliance—The policy of sitting on the safety valve—The consequent explosions—The problems consequently prepared for Francis Joseph—The Head of the House of Habsburg—Inseparable connection between the events of his public and private life | 1 |

| Chapter II | |

| The House of Habsburg from the standpoint of Eugenics—The “Habsburg jaw”—Degeneracy the consequence of consanguineous marriages—Sound physiological instinct of King Cophetua—And of those Habsburgs who have followed his example—Morganatic marriages—The family organism fighting for its life—Has Francis Joseph understood?—Indications that he has understood in part | 10 |

| Chapter III | |

| Francis Joseph’s ancestors—Francis, Duke of Lorraine—Francis II.—Leopold II.—Collaterals—The Spanish marriages of the Habsburgs—Their alliances with Portugal, the various Bourbons, and the Wittelsbachs of Bavaria—Moral and mental defects thus perpetuated and emphasised—Francis Joseph as the sane champion of a mad family | 20[xii] |

| Chapter IV | |

| Francis Joseph’s childhood—The severe education which prepared him for his rôle—Difficulties of that rôle—The Liberal revolt against the Metternich system—The idea of nationality—Hübner’s surprise that anyone should object to Austrian rule—Every Austrian a policeman at heart—The Italian rising of 1848—Francis Joseph in action—Radetzky’s remonstrances—Francis Joseph’s return to his studies | 29 |

| Chapter V | |

| The risings of 1848—Princess Mélanie Metternich’s excited account of it—Disorderly flight of Metternich from Vienna—The House of Habsburg saved by “three mutinous soldiers”—Abdication of the Emperor Ferdinand in favour of his nephew, Francis Joseph—Hübner’s description of the ceremony | 39 |

| Chapter VI | |

| Attitude of the Hungarians towards Francis Joseph—They denounce him as a traitor, and banish him from Hungary—Contempt of Austrians for Hungarians—The conquest of Hungary with Russian help—Repression and atrocities—Women flogged by order of Marshal Haynau—Marshal Haynau himself flogged by Barclay and Perkins’ draymen in London, and spat upon by women in Brussels—Popular song written on that occasion | 51 |

| Chapter VII | |

| Why Francis Joseph was called “The child of the gallows”—His affront to Napoleon III., and its consequences—The Bach system and the objections to it—Francis Joseph’s bonhomie—The attempt on his life—Impressions formed of him by the King of the Belgians, and Lady Westmorland—The story of his romantic marriage | 64 |

| Chapter VIII | |

| The failure of the marriage—Difficulty of explaining it—The two conflicting personalities—Francis Joseph’s personality obvious—The Empress Elizabeth’s personality mysterious—Her sympathy with the Hungarians, and its political importance—Her confession of melancholy | 77[xiii] |

| Chapter IX | |

| Francis Joseph’s Egeria—Elizabeth’s mother-in-law—Elizabeth’s quarrels with etiquette—The beginnings of estrangement—The functions of Countess Marie Larisch in the imperial household—Captain “Bay” Middleton—Nicholas Esterhazy—Elizabeth’s fairy story—Her cynical attitude towards life | 86 |

| Chapter X | |

| “The Martyrdom of an Empress”—Correction of inaccuracies contained in that popular work—Francis Joseph’s friends—“A Polish Countess”—Frau Katti Schratt—Enduring attachment—Rumour of morganatic marriage—Interview with Frau Schratt on that subject—“Darby and Joan” | 99 |

| Chapter XI | |

| Francis Joseph’s passion for field sports—Enthusiasm of a nation of sportsmen for a sportsman Emperor—Anecdotes of sport—Estrangement of the Emperor and the Empress—The Empress’s departure for Madeira—Her wanderjahre—Her attitude towards life—The keeping up of appearances | 113 |

| Chapter XII | |

| Francis Joseph’s snub to Napoleon III.—Proposal to address him as “Sir” instead of “Brother”—The consequences—Napoleon asks: “What can one do for Italy?”—Austria at war with France and Italy—The crimes committed by Austria in Italy—Battles of Magenta and Solferino—Francis Joseph compelled to surrender Lombardy, but allowed to retain Venetia | 122 |

| Chapter XIII | |

| An interval of peace—Beginnings of trouble with Prussia—Habsburg pride precedes a Habsburg fall—Refusal to sell Venetia to Italy—Italy joins Prussia—The war of 1866—The disaster of Sadowa—Benedek’s failure—Shameful treatment of Benedek by the Empire—Vain attempts to conciliate him—His widow’s comments | 132[xiv] |

| Chapter XIV | |

| Francis Joseph comes to terms with Hungary—His famous interview with Francis Deák—“Well, Deák, what does Hungary demand?”—Dualism—The objection of the Slavs to Dualism—Coronation at Buda—Andrassy, whom he had hanged in effigy, becomes his Prime Minister | 143 |

| Chapter XV | |

| Attitude of Austria in the Franco-German War—Proposed alliance of France, Italy, and Austria against Prussia—General Türr’s interview with Francis Joseph—Victor Emmanuel’s conditions—The bargain concluded—The French plan of campaign drafted by the Archduke Albert—Beust’s fetter to Richard Metternich—Reasons why the Austrian promises were not fulfilled | 148 |

| Chapter XVI | |

| Austrian expansion in the Balkans—Occupation of Bosnia—Problem of Servia Irredenta—Postponement of the day of reckoning—Luck of the Habsburgs in public life—Calamities dog them in private life—List of Habsburg fatalities during Francis Joseph’s reign | 158 |

| Chapter XVII | |

| Francis Joseph’s brother Maximilian—Invited to be Emperor of Mexico—Hesitates, but consents to please his wife—Resignation of his rights as a Habsburg—The Pacte de Famille and the quarrel about it—The compromise—The last meeting of the brothers—Maximilian’s melancholy—He composes poetry—He receives the benediction of the Pope and departs for his Empire | 164 |

| Chapter XVIII | |

| Vanity and nervousness of the Empress Charlotte—Evil omens which frightened—Her journey to Europe to seek help for Maximilian—Her cold reception by Napoleon III.—Symptoms of approaching insanity—Her madness—Maximilian abandoned by the French—Attacked by the Republicans—Captured at Queretaro—Francis Joseph’s vain attempt to save him—His trial and execution | 176 |

| Chapter XIX | |

| Habsburgs and Wittelsbachs—Which is the madder House?—Insanity of the Empress Elizabeth’s cousin, Ludwig II. of Bavaria—His eccentricities—His tragic death—Grief of the Empress—Suicide of Elizabeth’s brother-in-law, the Comte de Trani—Tragic death of the Archduchess Elizabeth | 187 |

| Chapter XX | |

| The Crown Prince Rudolph—His quarrel with the German Emperor—His affability and his hauteur—A spoiled child—His search for a wife—Marriage to Princess Stéphanie—Disappointment and disillusion—Stéphanie’s book—“A long, long, terrible night has gone by for me”—Mary Vetsera and her family—How Mary Vetsera was taken first to the Hofburg and thence to Meyerling | 193 |

| Chapter XXI | |

| What the Archduchess Stéphanie knew—What Rudolph knew that she knew—The search for Mary Vetsera by her relatives—The news of the Meyerling tragedy—The two official versions—The many unofficial versions—The attempt to hush the matter up—Mary Vetsera’s letter to Countess Marie Larisch | 208 |

| Chapter XXII | |

| Fantastic legends of the Meyerling tragedy—Talks with the Crown Prince’s valet—Foolish story given by Berliner Lokal Anzeiger—What the Grand Duke of Tuscany knew—What Count Nigra knew—What Countess Marie Larisch tells—Her story confirmed from a contemporary source—Doubts which remain in spite of it—Was it suicide or murder? | 218 |

| Chapter XXIII | |

| The Archduke John Salvator—His many accomplishments—His criticisms of his superiors—His disgrace at Court—His love affair with an English lady—“Your darling Archduckling”—His proposal to abandon his rank and earn his living as a teacher of languages—His love affair with Milly Stübel—He quarrels with Francis Joseph, takes the name of John Orth, and leaves Austria | 232[xvi] |

| Chapter XXIV | |

| John Orth—Had he been plotting with Rudolph?—Indirect confirmation of story told by Countess Marie Larisch—Did John Orth really marry Milly Stübel?—Failure to find the proofs of the marriage—John Orth’s letters written on the eve of his departure for America—Disappearance of his ship off Cape Horn—Is John Orth really dead?—Examination of the reasons for believing that he is still alive | 244 |

| Chapter XXV | |

| The revolt of the Archdukes—Instructive analogies—Later years of the Empress Elizabeth—Her manner of life described by M. Paoli, the Corsican detective—Her fearlessness—Her superstitions—Various evil omens—The last excursion—Assassination of the Empress at Geneva—How Francis Joseph received the news | 259 |

| Chapter XXVI | |

| “Austria’s idiot Archdukes”—A catalogue raisonné—The Emperor’s brothers—The Archduke Rainer—The Archduke Henry and the actress—The Archduke Louis Salvator, the Hermit of the Balearic Islands—The Archduke Charles Salvator—The Archduke Joseph—The Archduke Eugène and his vow to be “as chaste as possible”—The Archduke William and his courtship in the café—The Archduke Leopold—The awful Archduke Otto and his manifold vagaries | 272 |

| Chapter XXVII | |

| The centrifugal marriages of the Habsburgs—Francis Joseph’s attitude towards them—His attitude towards Baron Walburg, the Habsburg who had come down in the world—Where he draws the line—His refusal to sanction the marriage of the Archduke Ferdinand Charles to the daughter of a high-school teacher—The Archduke resigns his rank and becomes Charles Burg—Marriage of the daughter of Archduchess Gisela to Baron Otto von Seefried zu Buttenheim | 284[xvii] |

| Chapter XXVIII | |

| The marriage of Archduchess Stéphanie to Count Lonyay—Attitude of the King of the Belgians towards that marriage—Attitude of Francis Joseph—He sanctions the union, but snubs the bridegroom—Marriage of the Archduchess Elizabeth to Otto von Windischgraetz—Francis Joseph’s approval—The Windischgraetzes raised to the rank of Serene Highnesses | 294 |

| Chapter XXIX | |

| The Archduke Francis Ferdinand—An invalid who delayed to marry—Report of his betrothal to the Archduchess Gabrielle—Announcement of his betrothal to Countess Sophie Chotek—Anecdotes of the courtship—Indignation of the Archduchess Gabrielle’s mother—Attitude of Francis Joseph—He permits the marriage on condition that it shall be morganatic—Francis Ferdinand compelled to swear a solemn oath that he is marrying beneath him, and that his children will be unworthy to succeed him—Reason for doubting whether he will eventually be bound by his oath | 301 |

| Chapter XXX | |

| The “terrible year” of the Habsburg annals—Proceedings of Princess Louisa of Tuscany—The taint inherited from the Bourbons of Parma—Princess Louisa’s suitors—Her marriage to Prince Frederick August of Saxony—She bicycles with the dentist—She runs away to Switzerland with her brother, the Archduke Leopold, and her children’s tutor—Attitude of the Courts towards her escapade—Official notice on the subject in the Wiener Zeitung | 315 |

| Chapter XXXI | |

| The romantic Quadruple Alliance—The jarring notes—Princess Louisa’s objections to her brother’s companion Fräulein Adamovics—The sentimental life of the Archduke Leopold—He becomes “Herr Wulfling,” and marries Fräulein Adamovics—Herr and Frau Wulfling run wild in woods—Herr Wulfling divorces his wife and marries again—His confidences to Signor Toselli—Princess Louisa’s conception of the Simple Life—Her manners shock the Swiss—She dismisses M. Giron—Her marriage to Signor Toselli | 326 |

| Chapter XXXII | |

| The summing up—The probable future of Austria—The probable future of the House of Habsburg—Questions both personal and political which will be raised when Francis Joseph dies—The extent to which he has been “in the movement”—The faithful companion of his old age | 341 |

| INDEX | 353 |

| THE EMPEROR FRANCIS JOSEPH (from a recent portrait by Bieber) | frontispiece |

| THE EMPEROR FRANCIS JOSEPH AT THE TIME OF HIS ACCESSION IN 1848 | To face page 52 |

| THE EMPRESS ELIZABETH OF AUSTRIA | 82 |

| THE COUNTESS MARIE LARISCH AT THE TIME OF HER MARRIAGE | 96 |

| THE EMPEROR FRANCIS JOSEPH IN 1866 | 138 |

| MAXIMILIAN, EMPEROR OF MEXICO | 166 |

| CHARLOTTE, WIFE OF MAXIMILIAN, EMPEROR OF MEXICO | 180 |

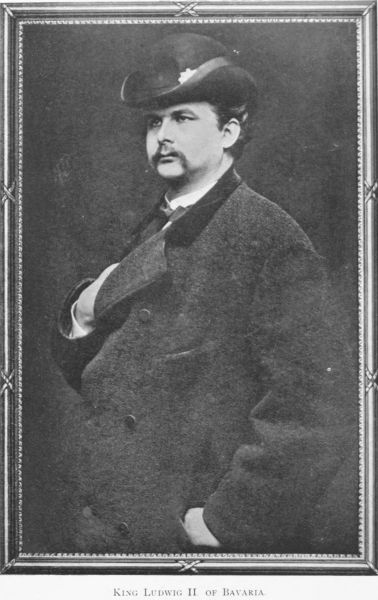

| KING LUDWIG II. OF BAVARIA | 190 |

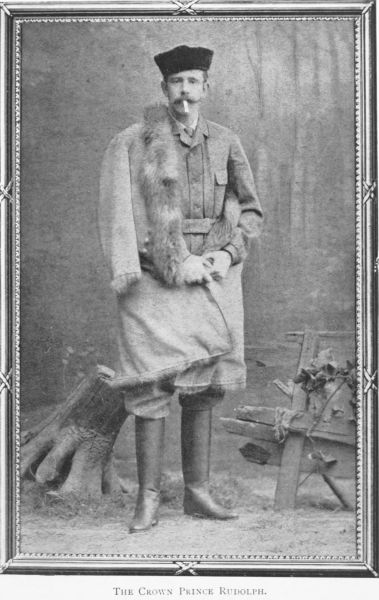

| THE CROWN PRINCE RUDOLPH | 196 |

| THE HOFBURG, VIENNA | 204 |

| THE CROWN PRINCESS STÉPHANIE | 210 |

| THE BARONESS MARY VETSERA | 224 |

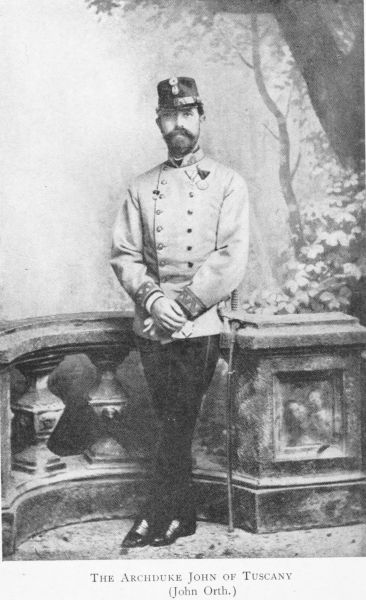

| THE ARCHDUKE JOHN OF TUSCANY (John Orth) | 254 |

| THE ARCHDUKE FRANCIS FERDINAND | 302[xx] |

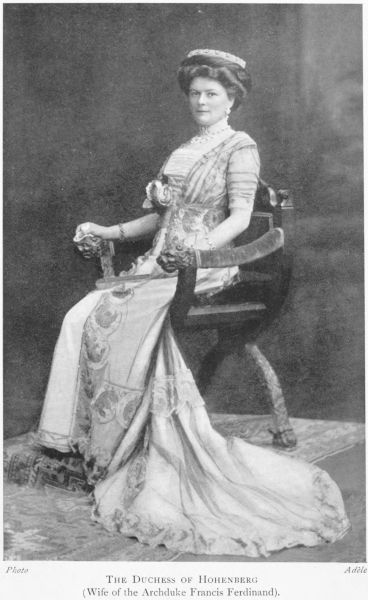

| THE DUCHESS OF HOHENBERG (wife of the Archduke Francis Ferdinand) | 312 |

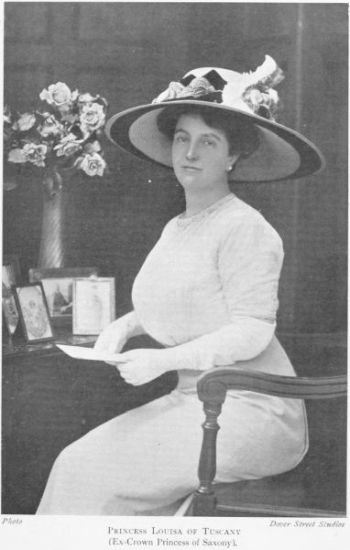

| PRINCESS LOUISA OF TUSCANY (Ex-Crown Princess of Saxony) | 338 |

| FRAU SCHRATT | 350 |

The collapse of the Holy Roman Empire—The impossibility of reviving it—The German Federation—The Holy Alliance—The policy of sitting on the safety valve—The consequent explosions—The problems consequently prepared for Francis Joseph—The Head of the House of Habsburg—Inseparable connection between the events of his public and private life.

In order to clear the way, and set the stage for the drama of the Emperor Francis Joseph’s life, we must go back to the dissolution of that Holy Roman Empire of which the Emperor of Austria was, at the end, the titular head. Happily, we have not very far to go.

The Holy Roman Empire—in fact, as a cynic has said, neither Holy nor Roman, and scarcely worthy to be called an Empire—collapsed in the Napoleonic wars. The Battle of the Nations at Leipzig, the “world’s earthquake” at Waterloo, the Congress of Vienna: none of these things availed to set the Holy Roman Empire on its feet again.

Perhaps a really great man might even then have[2] been able to restore it and make something of it, using it as a decorative setting for glorious achievements; perhaps not. The experiment was not tried, because there was no great man available to try it. The sovereigns of those days, with the sole exception of Alexander of Russia, were pitifully lacking in personal prestige. Whatever Napoleon had failed to do, he had at least succeeded in destroying the prestige of the hereditary representatives of ancient dynasties. The House of Habsburg, in spite of Napoleon’s marriage to a daughter of the House, had suffered as much indignity as any other royal family, and more than most. That marriage, indeed, was itself esteemed an indignity; even the old friends of the House were doubtful whether it still deserved respect.

Moreover, while Austria was rather weak, Prussia was very jealous—not altogether without reason. In the earlier stages of the final combination against Napoleon, Prussia had borne the burden and heat of the day, while Austria sat, with a double face, shilly-shallying on the fence. Now, it might be said, Austria represented the Past and Prussia the Future of the German world; and the Future was in no mood to tolerate proud airs or lofty pretensions from the Past. In the absence, therefore, of a commanding personality among the sovereigns, the revival of the Holy Roman Empire was impossible; and the centre of gravity of the German world was shifting.

Still, something had to be done; some organisation had to be contrived to give cohesion to the medley and provide the Continental Concert with[3] a reasonable prospect of a quiet life. So there sprang into being two organisations which concern us:—

Their detailed history need not delay us; but we must pause to see how they created the difficulties with which Francis Joseph, coming to throne as a boy of eighteen, had to cope, and posed the problems which he would have either to solve for himself or to see roughly, and even violently, solved for him by others.

Just as the Holy Roman Empire was scarcely worthy to be called an Empire, so the German Federation was scarcely worthy to be called a Federation. It was loose and cumbrous, inefficient and inert. There was no Federal Tribunal, no Federal army, no Federal diplomatic machinery; in all these matters the component States—ruled by thirty-eight separate sovereigns—retained their independence. The Federal Assembly, which met at Frankfurt, was, in effect, only a Congress of the Ambassadors of those States, with the Austrian Ambassador in the chair. No important step could be taken without the unanimous consent of the Ambassadors; and there was no important piece of business on which they were all of one mind. The position of Austria at the head of the Assembly was one of dignity without authority, conferring little more actual power than falls to the president of a debating society.

[4]

So loose an arrangement obviously could not endure. One of two things was bound to happen; the bonds of union must, in the course of time, either be tightened or be broken. The seeds of destruction were present in the organisation from the first in the shape of Austro-Prussian jealousy: that jealousy between the Past and the Future to which we have referred. The interests and aspirations of these two dominant States conflicted. Neither of them was strong enough to bring the other to heel; neither of them was weak enough, or humble enough, to acquiesce in the other’s hegemony. It remained only for one of them to turn the other out of the Federation, and fashion a real Federation—a real Empire, perhaps—out of the remaining constituents. That inevitable process—delayed for more than fifty years, but eventually altering the whole outlook of Austrian policy—was to provide the central problem of Francis Joseph’s reign; but many other problems, hardly of less significance, were first to arise out of the programme of the Holy Alliance.

The Holy Alliance, of course, was, in fact, no more Holy than the Holy Roman Empire, and was, perhaps, hardly worthy to be called an Alliance. It was an agreement, or mutual understanding, rather than an Alliance, inspired by hatred and terror of the new ideas disseminated by the French Revolution; and those are hardly unjust who describe it as a conspiracy, suggested by Metternich, and acquiesced in by the principal Continental sovereigns, for keeping all subject peoples in the places which the Congress of Vienna had assigned to them.[5] And that in a double sense. In the first place, autocratic forms of government were to be maintained in all countries which the Holy Three regarded as within their sphere of influence. In the second place, subject nationalities were to be kept in subjection to the Powers which the Settlement of 1815 had placed in authority over them.

It follows that the policy of the Holy Alliance was a policy of sitting on safety valves; and its history is the history of a series of Conferences and Congresses held to decide who should sit on which safety valve in the name of all. It was agreed, for instance, that Austria should sit on the safety valve in Naples, and that France should sit on it in Spain; and there was much talk—though also much difference of opinion—about sitting on the safety valves in Portugal and Greece. The Holy Alliance fell to pieces, after a much shorter life than that of the Holy Roman Empire, because Russia maintained against Austria, and England maintained against France, that certain safety valves should not be sat upon.

Moreover, safety valves were many, and the upward pressure was of a continually increasing force. If Metternich and Castlereagh, and the Emperors of Austria and Russia, and the King of Prussia, had, like the Bourbons, “learnt nothing” from the French Revolution and its sequel, the common people, from university professors to artisans, had learnt much. They might desire a breathing-time before committing themselves to desperate courses. The breathing-time[6] might be protracted because the despotisms were reasonably benevolent towards people who did not meddle with politics; because the administration was honest, and the taxes were not oppressive. Still, sooner or later intelligent men were bound to tire of submission, and clamour for Parliaments and the recognition of “nationalities.” Byron—the friend of the Carbonari before he was the friend of Greece—was hounding them on to do so.

In England Byron was notorious for his indecorum; but, on the Continent, he was famous for his audacity. The improprieties of “Don Juan” did not shock Continental Liberals; but its courageous political criticisms stirred them. The lines over which they gloated—though they must have had a difficulty in translating them—were such lines as these:—

Such passages—and there are plenty of them—express the temper to which the Continental Liberals were gradually coming. When they came to it, and found such men as Metternich, and Bomba of Naples, and Charles X. of France, sitting on the safety valves, explosions could by no means be prevented. The political history of the period is the history of those explosions and their consequences; and we all know that there were two principal series of such explosions—the explosions of 1830, and the explosions of 1848. The noise of the first detonations[7] was, as it were, a salute fired in the year of Francis Joseph’s birth; the louder roar of the second greeted his accession.

First Italy and then Hungary exploded; and Francis Joseph, as a boy of eighteen, had to face the confusion and try to calm it. The story of his bearing in the presence of the turmoil must not be anticipated; but we may look sufficiently ahead to note that a new Austria, differently constituted, and looking out of a new window in a new direction, had gradually to be re-created out of what might very well have been a wreck. The old Austria over which Francis Joseph began to reign in 1848 was a Teuton Power holding the most prosperous provinces of Italy in its iron grip. That grip has been reluctantly relaxed until only the pressure of one little finger remains; and the new Austria over which Francis Joseph rules to-day has only a small Teuton nucleus, associated with a Magyar nucleus nearly as large, trying in conjunction with it to assert predominant partnership in a large and increasing community of Slavs, and casting envious, but not very hopeful, glances across the Danube towards the Balkan States and the Ægean harbours.

So great has been the evolution accomplished within the reign of a single ruler: a ruler who, at the beginning of his reign, did not dare to set his foot in his own capital, and, long before the end of it, had come to be regarded as the one indispensable man in the Empire—the one man whose life must be preserved and prolonged at all hazards, for fear lest his death should entail the collapse of the edifice[8] which he had reared—the one man who sometimes appeared to command the affection of all his subjects. It would be a striking story, even if one related the Emperor’s political achievements without reference to his personal life; but the two things, though commonly separated by political historians, are not really separable.

Certainly they are not so separated by his own subjects. They not only admire the statesman who has acquired a prestige to which he was not born, and has used it to recover by diplomacy what he has lost in war; they also cherish an affectionate sympathy for the man at whom calamity has dealt blow after blow, whom no blow, however cruel, has struck down, and who, in spite of innumerable sorrows, has continued to confront the world with a dignified, if melancholy, composure. He has had, they perceive, no less trouble with his family than with his Empire; and they have sometimes thought of him—or at least been tempted to think of him—as the one splendidly sane member of an eccentric and decadent House.

It follows that one must write of Francis Joseph, not only as an Emperor, but also as a Habsburg—the head of the most interesting of all the royal houses: a House whose members, unpredictable in their insurgent extravagances, have, again and again, moved the Courts and Chancelleries of Europe to consternation. Our picture must be, not only of a great and successful ruler, but also of a brave old man, tried in the fire but not consumed by it, bowed down by sorrows but not broken by them, maintaining[9] the mediæval majesty of royal caste in the presence of his peers, at a time when other Habsburgs—one Habsburg after another—were flinging the prejudices of royal caste to the winds and making, as it must have seemed to him, sad messes of their lives, after the manner of those reprobate relatives who, even in middle-class families, are spoken of, if at all, with bated breath.

That being our theme—or a portion of it—we may next speak of the Habsburgs collectively; and we will begin by considering what the eugenists have to say about them.

[10]

The House of Habsburg from the standpoint of Eugenics—The “Habsburg jaw”—Degeneracy the consequence of consanguineous marriages—Sound physiological instinct of King Cophetua—And of those Habsburgs who have followed his example—Morganatic marriages—The family organism fighting for its life—Has Francis Joseph understood?—Indications that he has understood in part.

The House of Habsburg furnishes the “horrible examples” in two recent works on the new science of Eugenics: L’hérédité des Stigmates de Dégénérescence, by Dr. Galippe, and L’Origine du Type familial de la Maison de Habsburg, by Dr. Oswald Rubbrecht. The arguments in both cases are based, not only on a study of history, but also on a collation of portraits; and though the writers differ on some points of detail, their general conclusions are identical. For both of them the Habsburgs are “degenerates”; both of them attribute the degeneracy to the same cause. It is, they agree, the cumulative effect of what is technically called “in-breeding”—of a long succession of inter-marriages among comparatively near relatives.

One hears of the physiological law thus violated, whenever the question of a marriage between cousins[11] is mooted. The tendency of such a marriage, we are always told, is to perpetuate and accentuate typical characteristics and weaknesses, both physical and moral. A single marriage between cousins may produce no perceptible evil result; and one can cite cases in which it appears to have produced remarkably brilliant results.[1] But a series of such marriages, continued through generation after generation, invariably and inevitably tells. The family, or the community, in which such unions are the rule, loses vigour and develops peculiarities—a special, readily recognisable, physiognomy, and an unstable mental equilibrium. The transmitted eccentricities—more particularly the mental eccentricities—may skip a generation or leave an individual exempt; but they are always lurking in the background—always to be expected to reappear.

[1] Darwin married his first cousin, and all his sons were men of remarkable ability.

It has been so, and is so, according to Drs. Rubbrecht and Galippe, with the Habsburgs. We have all heard of the “Habsburg jaw”; and Dr. Rubbrecht traces it to its mediæval source, and, standing before a long row of family portraits, carefully and scientifically depicts the Habsburg face:—

“In addition to the underhung lower jaw and the large lower lip, the Habsburg physiognomy presents the following characteristic features: excessive length, and, sometimes, excessive size of the nose; ‘exorbitism,’ more or less pronounced, with a forehead often of considerable height. One would say[12] that the head, squeezed in by lateral pressure, had undergone a concomitant vertical allongation, and had been stretched, and pulled up and down at the same time. According to Dr. Galippe, the lateral flattening of the skull is the fundamental characteristic, and all the other abnormalities follow from it.”

That is what Dr. Rubbrecht makes of the portraits. He generalises only as a student of physiognomy, and does not discuss mental and moral issues, or presume to predict the future. Dr. Galippe is more outspoken:—

“The Habsburgs” (he writes), “having, by their intermarriages, developed a degenerate taint, and having transmitted it, either separately or in conjunction with other taints, both physical and psychical, to the families matrimonially allied with them, have brought into existence a specific type of human animal, by the same means which the breeders of dogs and horses employ for the creation of a new sub-species.”

As for the general consequences of such in-breeding, he continues:—

“Even those aristocratic families which present no original mark of degeneracy disappear quickly. It follows, a fortiori, that those families which, possessing such characteristics, perpetuate them by contracting marriages within the degrees of consanguinity, are doomed to a still more speedy extinction.”

As for the case of the Habsburgs in particular, he concludes:—

[13]

“The Habsburgs of Spain have long since been swept off the stage of history, disappearing in sterility or insanity. The Habsburgs of Austria, numerous though the representatives of the House are at the present time, will end by disappearing in their turn as an historic family, if they persist in their errors,—that is to say, in their marriages with blood relations.”

It is a new way of looking at an old problem,—a new thought suggested by the latest of the sciences; and it opens the door to reflections of great and urgent moment to many other royal houses besides that of Habsburg. In a general way, it has long been held to be almost as improper for Kings and Queens to marry their subjects as for angels to marry the daughters of men. A purer and bluer blood ran in their veins than in the veins of their subjects; and to adulterate that blue blood with red blood was to degrade it. They must, therefore, seek their brides and bridegrooms within the magic circle. Kings must marry Queens, and Princes must marry Princesses; and the distinctive exclusiveness of reigning houses must be maintained by a succession of unions between cousins.

That view of the matter has continued to prevail in royal circles—and also in high political and diplomatic circles—long after the students of heredity have established conclusions unfavourable to such courses. The arguments can hardly have failed to reach the ears of those whom they concerned; and the feeling—tacit, if not avowed—has presumably been that Kings, and[14] Queens, and Princes and Princesses are so great and good and glorious that the laws of Nature do not apply to them. But that is not the case. Science shows that Kings cannot override the laws of Nature even in the countries in which they are permitted to override the laws of the land; that the price which Nature exacts for exclusiveness is degeneracy; that hardly any royal family anywhere has failed to pay that price; that the percentage of insanity has, through the ages, been higher among hereditary rulers whose blue blood has thus been protected from admixture than in any other class of the community; and that the sound physiological instinct is that on which King Cophetua acted in the legend, when the bare-footed beggar-maid appeared before him:—

It is this example of King Cophetua—and the moral which the eugenists read into it—that we shall need to bear in mind when we endeavour to appreciate those incidents in the latter-day history of the House of Habsburg which are commonly supposed, whether rightly or wrongly, to have been most distressing to the head of the family. That history has largely, and indeed mainly, if not quite entirely, been a history of revolt on the part of the sons—and[15] even the daughters—of the House against the splendid restrictions and inherited obligations which hedged them about as members of an uniquely illustrious race.

The revolt has expressed itself in many ways: some of them, in the world’s view, creditable and even honourable; others in a greater or less degree scandalous. We have seen—and we shall see yet again in these pages—one Habsburg throwing off the panoply of state, to live his own mysterious life in the remote Balearic Isles, and another Habsburg disappearing for ever—unless those are right who assure us that he bides his time, in hiding, for some dark political reason, and will “come again”—as the navigating officer of a merchant vessel. There have also been intrigues which have ended in tragedy, and morganatic marriages with actresses and other persons deemed “impossible” in imperial circles; and there has been at least one elopement of a Habsburg Princess, who, having failed to live harmoniously with a Crown Prince, found that even a professional pianist could not permanently satisfy her craving for romance.

One knows the ordinary comment on these proceedings: “All the Habsburgs are mad,—all of them except Francis Joseph; and here is another Habsburg proving himself (or herself) as mad as the others, if not madder.” The remark is not profound; but it is often, in a rough way, true. John Orth, “Herr Wulfling,” Princess Louisa of Tuscany:—all these (and not these only) have done strange things,—things which one would hesitate to[16] put forward as the sole and unsupported proofs of the possession of well-balanced minds. This is not the page for the detailed account of such proceedings; but it is pertinent and proper, even here, to remark the startling frequency of their occurrence. It is not a case of the discovery of a single skeleton in a single cupboard—a phenomenon which any research into any family history is apt to bring to light. The impression, when one reviews the recent annals of the House of Habsburg, is of continuous rattling of skeletons in all the cupboards, and of one sane and strong man—the accepted and now the hereditary Head of the House—going gravely through his troubled life, not unmoved, indeed, by the ghostly noises, but, at least, without allowing his composure to be too visibly disturbed by them: a man of whom one may say, giving a somewhat new sense to old and hackneyed lines:—

But that is not the only view of the matter which it is permissible to take. One may also, with the conclusions of science to back one, regard the eccentricities of the more eccentric Habsburgs, if not as the best proofs of sanity that they are capable of giving, then as instinctive and desperate, if not always very intelligent, endeavours to escape from the imminent fate which the eugenists have foretold for them. The family, we may take it, no less than the individual, is an “organism,” albeit only partly conscious of itself; and our spectacle, we[17] may add, is that of an organism blindly fighting for its life. The fight may not be very wisely conducted, not having been begun until the work of destruction was too far advanced; but it is nevertheless a fight worth fighting, and one of which we should follow the vicissitudes, not with horror or with merriment, but with intelligent sympathy. For degeneracy is too high a price to pay for haughty exclusiveness; and it is better to flee from the City of Destruction late in the day, followed and attended by the cry of scandal, than to remain in it and be overwhelmed.

That, at any rate, is the appreciation of the Habsburg scandals—or of a good many of them—which will commend itself to eugenists and sociologists, who will esteem the revolts sound in principle, even though they allow them to be occasionally extravagant in detail. The individual makers of the scandals need not be assumed to have acted from any higher or deeper motive than the satisfaction of what has more than once proved to be only a passing inclination. The whole circumstances of their upbringing, and the precepts of duty and propriety impressed upon them from childhood, make that unlikely. But the physiological instinct behind the admitted motive has been a sound one. Looked at from the viewpoint of the individual, it had been the instinct of King Cophetua; looked at from the point of view of the race, it has been the instinct of self-preservation.

It has been the tragedy—or one of the tragedies—of Francis Joseph that the years of his reign have[18] coincided with the years of this stage in the Habsburg struggle for continued existence. Chosen for his august and exalted post as the sanest and healthiest Habsburg available—albeit the son of an epileptic father and the nephew of an epileptic uncle—he has looked down from above on the exciting incidents and varying vicissitudes of that struggle. One does not know whether to regard his tragedy as the greater on the assumption that he understood the inner meaning of the spectacle or on the assumption that he did not understand it. In the former case there would be more of pathos, in the latter case more of irony, in the drama; but it is impossible to say for certain whether he has understood or not.

The probability, in the lack of direct evidence, is that he has understood in part. One might draw that inference from his occasional indulgence, as well as from his occasional severity, towards the rebels against the laws, both written and unwritten, of his House; and one has no right to infer the contrary from the fact that he himself has not rebelled. He is a Habsburg as well as an Emperor, and may very well have felt the impulses which appear to have become common to the race, though he has had both exceptional reasons and exceptional facilities for repressing them. One knows, at any rate, that he, like so many other members of his family, has sought, and won, the friendship of women outside the charmed circle of the royal families, and that the lady in whose company he seems, in the last years of his long life, to find the[19] most agreeable respite from the cares of State, is not an Archduchess, and was once an actress. That fact must surely have helped him to understand.

But these are matters for subsequent consideration. The ground is now clear; and we may proceed, without further delay, to genealogy and biography.

[20]

Francis Joseph’s ancestors—Francis, Duke of Lorraine—Francis II.—Leopold II.—Collaterals—The Spanish marriages of the Habsburgs—Their alliances with Portugal, the various Bourbons, and the Wittelsbachs of Bavaria—Moral and mental defects thus perpetuated and emphasised—Francis Joseph as the sane champion of a mad family.

The Habsburgs can be traced back to the seventh century before we lose them in the crowd of common men. The branch of the family to which the Emperor Francis Joseph belongs is that known as the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, founded by the marriage of the Empress Maria Theresa to Francis, Duke of Lorraine, in 1736; and the House of Lorraine has an independent genealogy, only less ancient and illustrious than that of Habsburg itself, being descended, through the House of Anjou, from Hugues Capet, the ancestor of the royal house of France. Anjou was given, in 1246, by Saint Louis, to his younger brother Charles, whose grand-daughter married her cousin, Charles de Valois; and the House of Anjou kept the Duchy of Lorraine until Francis abdicated on the occasion of his[21] marriage, in favour of Stanilas Lecszinski, whose daughter married Louis XV.

This Francis seems to have been a mixed character, not entirely commendable. He is credited with virtue in his private life; but it is also related of him that he farmed taxes, lent money at usurious rates of interest, and acted as a kind of army contractor to Frederick the Great, at a time when that monarch was at war with Austria. He was the father of Marie-Antoinette, and also of the Emperors Joseph II. and Leopold II. Joseph left no issue, but Leopold, who married Marie-Louise, daughter of Charles III. of Spain, had a large family, only two members of which need be mentioned here:

1. Francis II., who became Emperor in 1792, and was on the throne when Napoleon broke up the Holy Roman Empire.

2. The Archduke John, whose romantic marriage with the daughter of a postmaster set a precedent for those morganatic unions which have recently become so frequent in the House of Habsburg.

Leopold II. is described by the historians as a benevolent despot—a reformer according to his lights—who displayed great intolerance in religious matters, and died young through the unbridled indulgence of his amorous proclivities. Francis II. is an Emperor of whom it would be necessary to speak evil at length, if he, and not his grandson, were the subject of this narrative: a double-faced and incompetent ruler, who needed all the help he got from Metternich; a petty domestic tyrant, who behaved abominably towards[22] his daughter Marie-Louise, his son-in-law Napoleon, and his grandson the Duc de Reichstadt. How he deliberately threw Neipperg at his daughter’s head for the express purpose of undermining the affection which her husband had, to his disgust, inspired in her, is a story which belongs to other pages than these. Here we will merely note that he married four wives, and by the second of them—Marie-Thérèse-Caroline-Josephine de Bourbon—had two sons, who now concern us:—

1. The Emperor Ferdinand, who succeeded to the throne in 1835, but bowed his head before the storm and abdicated in 1848, though he did not die until 1875.

2. The Archduke Francis Charles, who, as Ferdinand had no children, should have succeeded him, but whom his wife, the Archduchess Sophie, daughter of Maximilian I. of Bavaria, persuaded to resign his rights in favour of his eldest son, the present Emperor, Francis Joseph.

That is all the genealogy which we need for the moment. It shows us the Habsburgs as a feeble folk—getting feebler as times got more tempestuous; and it also shows us Francis Joseph launched upon his stormy political career at the age of eighteen—launched upon it as the rising hope of a decadent family—a youth of energy and promise, with no sign of decadence about him, supple but strong, exempt, as far as could be judged, from the family taints of physique and character, and designed to restore the threatened dignity of the Austrian Empire, by confronting the new era[23] in a new spirit. His accession will be our historical starting point; but, before we come to it, we must turn aside for a brief glance at some of those collateral ancestors whose traits, if there be anything in heredity, we may expect to see reappearing—not invariably, but here and there, and now and then—in their descendants, the Habsburgs of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The list of the allied houses includes, of course, practically the whole of Catholic Europe, and a portion of Protestant Europe as well. To attempt to review them all would be to lose oneself in an interminable maze; but the collateral sources of particular contamination can be noted, and we shall see house after house contributing—some of them only on one, but some of them on several occasions—its strain of madness to the great family with which it was its privilege to intermarry. We may begin with the House of Burgundy, and end with that of Bavaria, taking on our way the Houses of Spain, Portugal, Medicis, and Bourbon Parma.

Charles the Bold of Burgundy fell into a melancholy madness after his defeat by the Swiss at Morat, and died a madman. His daughter Marie, Duchess of Brabant and Countess of Flanders, married Archduke Maximilian of Austria, son of the Emperor Frederick IV. Their son, Philippe le Bel, married that daughter of Ferdinand of Arragon who is known to history as Joanna the Mad. Those are the unfavourable circumstances in which we see Habsburg blood introduced into the royal family of Spain; and the subsequent history[24] of the family presents two features pertinent to our survey:—

1. A long series of degenerates among the Kings and Infants of Spain.

2. A long series of marriages between Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs.

No full account of the manifestations of the madness of Spanish rulers, Princes, and Princesses can be given here; they are too numerous, and also too gross for general reading. The briefest of summaries must suffice. Joanna the Mad travelled all over Spain with her husband’s coffin, wailing and lamenting, at the top of her shrill voice, whenever the funeral procession halted. Joanna’s son, the great Emperor Charles V., lived on the border-line which separates genius from insanity, and was, at any rate, an epileptic, like that Archduke Charles whose campaigns against Napoleon were punctuated by untimely fits. His son, Philip II.—known to English history as the husband of our Bloody Mary—is described by the historians as “half-mad”; and Philip’s brother Charles was notoriously a homicidal maniac. Philip III. was comparatively sane; but even he tried to poison his sister. Charles II. was nicknamed “the bewitched,” and was so afraid of the dark that three monks had to sit every night at his bedside, in order that he might sleep in peace. Philip V. was, for years, a bedridden imbecile; and Ferdinand VI. was a victim of religious melancholia, Etc. The catalogue is far from complete;[25] but it may suffice as a preface to the statement that one finds eight or nine Spanish marriages in the Habsburg matrimonial annals.

One encounters a very similar list of lunatics in the annals of the royal House of Portugal; and with that house also the Habsburgs have again and again intermarried. The pathology of the Medicis and the multitudinous Italian Bourbons, whose blood also runs in the Habsburg veins, is hardly better; and it can scarcely have been in the expectation of introducing a healthier strain that they sought alliances with the Wittelsbachs of Bavaria. Sanity, in that house, is represented by the King who sacrificed his kingdom to the beautiful eyes of Lola Montez; madness by the Kings Louis and Otto, whose extravagances and eccentricities have been related in innumerable volumes of memoirs and newspaper articles, and who are Francis Joseph’s cousins.

Assuredly no Eugenist will assert that that heredity is good. On the contrary, the impression derived from a close examination of it is that of several strains of insanity and decadence converging, much in the way in which a multitude of Swiss mountain torrents converge to form the Rhone. But even that analogy is unduly favourable; for the sources from which fresh blood has been introduced into the family have not been indefinitely numerous. The same source has been tapped over and over again by the renewal of consanguineous marriages in one generation after another, with the result that the Habsburg type—with all its peculiar physical,[26] mental, and moral characteristics—has been perpetuated and emphasised.

The physical characteristics were long ago recognised by the family itself with pride, and by outsiders with a curious wonder akin to envy and admiration. Napoleon so remarked it at the time of his betrothal to Marie-Louise, as M. Frédéric Masson relates:—

“When” (M. Masson writes) “Lejeune, who had just arrived from Vienna, showed him a sketch of the Archduchess which he had made at the theatre, ‘Ah!’ he exclaimed in delight, ‘I see she has the Austrian lip.’”

In Brantôme, again, we find a much earlier reference to the feature. He tells us how Eleanor of Austria, the wife of Francis I. of France, examined the sculptured tombs of her ancestors at Dijon; and he proceeds:—

“Some of the bodies were in so good a state of preservation that she could distinguish many of their features, and, among other things, the shapes of their mouths. Whereupon she suddenly exclaimed, ‘Ah! I always thought we got our mouths from our Austrian ancestors; but I now see that we get them from Marie of Burgundy and the other Burgundians. If ever I see my brother the Emperor I will tell him so. Indeed, I think I will write to him on the subject.’ The lady who informed me of this told me that the Queen spoke as one who took pride in the characteristic; wherein she was quite right.”

[27]

That this physical peculiarity was, in the case of the Habsburgs, the outward sign of mental and moral divergences from the healthy norm was evidently as little suspected by Napoleon as by Brantôme. It is the discovery of the students of a comparatively new science; and it is a discovery of which the biographer must be careful to make neither too little nor too much. Eugenics is not yet an exact science; and the laws of heredity remain obscure. They are laws, it would seem, which, though generally true, cannot be relied upon to operate in any particular way in any particular case. The life of a family almost invariably confirms them, whereas the life of an individual may often appear to confute them; and we may often see genius flowering on the same plant as insanity.

The history of the Habsburgs in general—and the life of Francis Joseph in particular—supports that view of the matter. The Archduke Charles, who was so nearly a match for Napoleon, and actually beat him at Aspern, was not a very distant relative of the Archduke Otto who used to dance in a Vienna café, attired only in a képi, a pair of gloves, and a sword-belt. The Archduchess Christina, who proved such an admirable mother to the little King of Spain—though she has transmitted a double portion of the Habsburg jaw to him—was no less a Habsburg than the Princess who so signally and so publicly failed to find happiness in the love of Signor Toselli. And so on, and so forth; for the contrasts of the kind to which one could point are endless. One is left with the[28] impression that the family, taken as a family, is mad, but that certain isolated members of it have been as sane as the rest of us, and abler than the majority; and one needs the impression before one can justly appreciate the drama of Francis Joseph’s life.

He has stood before Europe, for more than sixty years, as the picked champion of the Habsburgs: picked not only for his ability, but also for his strength of character and conciliatory tact—for all those qualities, in short, which one looks for from a sane man in an exalted station. He started, as we have seen, under the burden of a singularly bad heredity; and he has carried that burden through life with patient endurance—and with an air of dignity—as if personally unconscious of the taint, while the lives of those nearest and dearest to him were furnishing undeniable proofs of it at every turn. He has shown himself, to conclude, the true head of the house, by nature as well as by pragmatic sanction.

So much made clear, we may proceed to chronicle the bald facts of his birth and childhood.

[29]

Francis Joseph’s childhood—The severe education which prepared him for his rôle—Difficulties of that rôle—The Liberal revolt against the Metternich system—The idea of nationality—Hübner’s surprise that anyone should object to Austrian rule—Every Austrian a policeman at heart—The Italian rising of 1848—Francis Joseph in action—Radetzky’s remonstrances—Francis Joseph’s return to his studies.

Francis Joseph was born at Schönnbrunn on August 18, 1830. His father was the Archduke Francis Charles, and his mother the Archduchess Sophie, daughter of Maxmilian I. of Bavaria. He grew up and was educated in the period of peace between the two great revolutionary storms which shook Europe free from the Metternich system: a period which begins with Metternich supreme, and ends with Metternich in flight from an angry mob. He owed his throne, the steps of which he mounted, as a lad of eighteen, in the midst of the second epoch of turmoil, to his mother’s influence. She was an able and imperious woman; she made up her mind that her son would make a better Emperor than either her brother-in-law[30] or her husband; she pulled the wires and got her way.

The boy’s education was thorough and practical: just the sort of education which he would have been given if his destiny had been in view from his birth. He was taught the whole duty of a soldier in each of the several branches of the service: to point a cannon as well as he could mount a horse; to dig a trench as well as he could handle a sabre or a rifle. He was also taken through complete courses of history, literature, mathematics, chemistry, astronomy, and natural history, instructed weekly in the maxims of statecraft by Metternich himself, and compelled to acquire innumerable modern languages: Hungarian, Czech, and Polish, as well as French, Italian, and, to a limited extent, English. It was an intellectual preparation which might easily have addled his brain, and does appear to have made him prematurely serious. Even before the troubles of his family compelled him to shoulder its responsibilities, he was remarked as being grave, earnest, and reserved: the good boy of his family, it was thought—and as clever as he was good.

Of course, there are anecdotes indicating that he loved his people—and, above all, loved his army—from his earliest years. The most famous of them shows him to us, moved to pity by the sight of a sentry sweltering in the August sun, stealing up behind him, and dropping a small coin into his cartridge-box, to the delight and admiration of his aged grandfather: a subject picture by Kriehuber keeps the memory of that incident alive. “Poor[31] man! But now he is not a poor man any longer,” he is said to have said, jumping about with joy at the thought that he had made someone happy. Very likely it is true; very likely it is also true that he, who was soon to be one of the best horsemen in his dominions, began life with a horror of horses. Those about him knew what sort of a man they wanted him to be, and did their best to make him such a man. There was a regular Habsburg system of education, though not all the Habsburgs have done credit to it. The great Maria Theresa had laid it down that “they must not be coddled or spoiled”; and the Emperor Joseph had expressed similar sentiments in emphatic language:—

“It may be enough for one of my subjects to say that, whereas his son will be of service to the State if he is well educated, the neglect to educate him does not matter, as he will have no public functions to perform. The case of an Archduke—a possible heir to the throne—is very different. The most important of all public functions—the government of the State—is absolutely incumbent on him. The question, therefore, whether he is or is not well educated, is one which it should be impossible to raise. He must be well educated; for there is no branch of the administration in which he might not do infinite harm if he had not the necessary knowledge to cope with his task and were unprovided with fixed principles of conduct.”

It is a prescription as admirable as any to be found in the copy-book; though the rigid application of it has not prevented a good many Habsburgs[32] from turning out, from the Habsburg point of view, badly. It is a call to every Habsburg in turn to “be a Habsburg,” in the sense in which George III.’s mother appealed to him to “be a King”; and it rests upon a conception of the House of Habsburg as a house specially and divinely called into being in order to practise the art of government in central Europe. One may almost say that it assumes a caste of anointed rulers differing from their subjects as angels differ from the children of men; but it stops short of the corollary that rulers are born, not made. It lays down, rather, that the caste, in order to retain and exalt its qualities as a caste, must always be specialising from infancy to age. In that way, and in that way alone, its members might dispense with genius.

On the whole, they have had to dispense with it: their figures do not tower above the figures of their ministers, like those of Alexander I. of Russia and Frederick the Great of Prussia. Metternich is not the only Austrian minister who has been infinitely greater than any of the Emperors whom he served. Not all of them, again, have continued to specialise a day after the compulsion of tutors was withdrawn. A great many of them, on the contrary—a constantly increasing number of them in these latter times—have openly revolted against every restriction which made the caste characteristic. But the caste has continued, buttressed by the system, an object of regard, and almost of veneration, thanks to certain model Habsburgs, who have consented to the restrictions, and profited by them. Francis Joseph steps[33] on to the stage of history as such a one: a specialised Habsburg, approaching nearer to genius than the others, but also gifted with a tactful adaptability which has enabled him to realise that the dead past must be allowed to bury its dead from time to time. Let us indicate the political troubles which called him into activity.

The revolutions of 1830 had been, in the main, abortive: a symptom of general discontent, but not its complete and successful expression. The work done at the Resettlement of 1815 had been shaken by it, but had not, except here and there—in Belgium, for instance—been upset; and that resettlement had been planned in the interest of reigning houses, not of peoples. The reigning houses continued to sit on the safety valve; and the steam which was trying to find vent through the safety valve consisted of:—

To both those groups of ideas the Austrian Government was bitterly opposed; with both of them it was to have trouble. Its political prisons were famous throughout Europe as the homes of distinguished men, and its subject populations seethed with discontent. The idea of nationality was particularly obnoxious to it because it did not itself repose upon a national basis. “Austria,” said Mazzini, with a gesture of disdain, “is not a country, but a bureaucracy”; and Austria was, in fact—what Metternich said that Italy was—a geographical ex-pression.[34] It simply comprised the possessions of the House of Habsburg, which had, for generations, added field to field by means of prosperous marriages,[2] or accepted territory as the recompense of services rendered in war. The Emperor of Austria was also King of Hungary, King of Lombardy, King of Bohemia, etc., etc.: the head, as it were, of an ancient firm formed to carry on the general purposes of government in central Europe, and regarding men and women merely as material to be governed.

[2] The idea was set forth in the famous hexameter line: Bella gerant alii: tu, felix Austria, nube.

The system had its advantages—it kept the peace provisionally in what might otherwise have been one of the cockpits of Europe. That was what the French diplomatist meant when he said that, if the Austrian Empire had not existed it would have been necessary to invent it. But it was not popular, and it tended to make every Austrian statesman a policeman at heart. Even Metternich was a policeman at heart: a policeman of genius—a policeman of wide culture and charming manners—but still a policeman. He and his subordinates simply could not understand that people of other races might object to being policed by Germans. The Germans, they considered, were the best policemen in the world; and that should be an end of the matter. Count Hübner—a most intelligent Austrian—threw up his hands in amazement at the obstinate prevalence of the contrary opinion:—

[35]

“To-day” (we find him writing in his diary) “the magic word which moves the masses—not the proletariate, but the intelligent public—is nationality. Germans, Italians, Poles, Magyars, Slavs! It is a formula capable of throwing the universe off its hinges—the lever which Archimedes sought in vain. The ringleaders have discovered it. With this lever they have, in the course of a few days, upset the old social system, and dazzled the eyes of the purblind with the deceptive promise of the perpetual happiness of the human race.”

The peoples of central Europe, in Hübner’s opinion, should have been as proud of their subjection to the House of Habsburg as the domestic servants whom Thackeray met on the top of the coach were of their position as the flunkeys of the Duke of Richmond. Italian national aspirations, in particular, seemed to him merely comical. He derided the Italians as mongrels—a medley of Gauls, Celts, Goths, Germans, Greeks, Normans, and Arabs; he recalled the internecine strife which had raged among their Republics in the Middle Ages. He comforted himself with the reflection that they spoke different dialects in different parts of the Peninsula, and he concluded: “I cannot believe in a United Italy.”

Yet Italy was being united—and the Austrian Empire was apparently crumbling into its component parts—at the moment when he wrote, in July, 1848. Already, from the beginning of that year, anxiety had been widespread; and, in February, events in France had given a signal of unmistakable significance. “If Guizot falls,” Mélanie Metternich[36] exclaimed, “then we are all lost.” Guizot did fall; and Louis-Philippe fell with him. The news reached Vienna; and it seemed as if Austria was in the melting-pot, though the trouble began, not in Vienna, but at Milan, where an Archduke reigned as Viceroy, and that sturdy octogenarian Radetzky commanded the army of occupation.

Charles Albert, King of Sardinia—the great-grandfather of the present King of Italy—had promised to be “the sword of Italy,” on one condition. He would not collaborate with mere conspirators, but if there were an insurrection he would march to the aid of the insurgents. His terms were accepted, and there was a riot which became a revolution, though, in its inception, it presented some of the distinguishing characteristics of comic opera.

The revolutionists began by decreeing that as the Austrian Government depended largely for its revenues on the tobacco monopoly, no one in Italy should smoke. Austrian soldiers retorted by swaggering through the streets of Milan, smoking several cigars at once. Female patriots knocked the cigars out of their mouths, and pelted them from the house-tops with flower-pots and other missiles; while male patriots, armed with various weapons, molested them in other ways. There was street fighting, and there were killed and wounded. The patriots were many; the garrison was small; Charles Albert was known to be coming. Radetzky had no choice but to withdraw his troops within the famous Quadrilateral of Fortresses, leaving the provisional government set up by the revolutionists in possession.[37] It seemed to the sapient Hübner a case of black ingratitude towards the admirable Austrian police.

But Austria was not, this time, to be beaten. Within the Quadrilateral Radetzky was safe; and, in due course, he marched out and defeated Charles Albert at Custozza. Few reinforcements had reached him, but they sufficed; and among the officers who came to serve under him was included Francis Joseph—not yet eighteen years of age. It was his first appearance in the field; and Radetzky was not particularly glad to see him. The scene which passed between the stripling and the veteran is best described in the Life of Radetzky included in General Ambert’s Cinq Epées:—

“Radetzky addressed the new arrival in peremptory military language. ‘Imperial Highness,’ he said, ‘your presence here is exceedingly embarrassing for me. Consider my responsibility in case anything should happen to you! If you should be taken prisoner, for instance, the accident would annihilate at a stroke any advantage which the Austrian army might have gained.’ ‘Marshal,’ replied Francis Joseph, ‘it is quite possible that it was unwise to send me here; but, as I am here, honour forbids me to depart without facing the enemy’s fire’; and his eyes filled with tears as he spoke.

“No objection could be taken to an explanation so simple and gallant; and it was agreed that the Archduke should take part in the next battle, which was fought a few days later (the battle of May 6, at Santa Lucia). Here are the precise words of the[38] report, addressed by Radetzky, immediately after that sanguinary struggle, to the Minister of War: ‘I was myself an eye-witness of the intrepidity displayed by the Archduke, when one of the enemy’s shells burst quite close to him.’”

“Austria does not lack Archdukes,” he said gallantly, when implored not to expose himself to danger; but his battle was only of the nature of a holiday treat. He was still in statu pupillari—occupied with the severe studies by which he was preparing himself for his great rôle; and when he had done enough for honour, he returned to them. It was then, or soon afterwards, that he was confidentially informed of the great trust about to be reposed in him; but the intimation neither puffed him up with pride nor disturbed his diligence. He brought out his books again—immense tomes dealing with Roman, civil, criminal, and canonical law—and resumed his reading, almost as if everything depended upon his passing an examination in high honours. Not if he could help it should the arrival of his hour find him unready for it.

And his hour was near, for the times were critical. Trouble at home had followed hard on the heels of the trouble in Lombardy, and, being more complicated, had been more difficult to deal with.

[39]

The risings of 1848—Princess Mélanie Metternich’s excited account of it—Disorderly flight of Metternich from Vienna—The House of Habsburg saved by “three mutinous soldiers”—Abdication of the Emperor Ferdinand in favour of his nephew, Francis Joseph—Hübner’s description of the ceremony.

If we want to look at the disturbances which broke up the old order in Austria through contemporary eyes, our most helpful document will be the Diary of Metternich’s wife, Princess Mélanie—so called, tout court, as an indication that she ranked, like the Archduchesses, as one of the Olympian goddesses of Viennese Society. One seems, as one reads it, to be listening to the shrieks of a fluttered bird; for Princess Mélanie understood as little as a bird would have understood, the true significance of the uprising. Sheer wantonness was, for her, the sole motive of the revolutionists; black ingratitude towards good rulers was their distinguishing characteristic; and the outcome of the agitation could only be “the end of all.” All that because the students and the artisans had announced that they desired a “Constitution.”

Already we have seen Princess Mélanie predicting[40] that, if Guizot fell, all was lost; and, after the events of February, 1848, in Paris, she saw horrors accumulating on horror’s head:—

“Poor Germany is already in a blaze. Never were times graver or more solemn. Every hour brings forth a fresh event, and fresh troubles are perpetually being added to those already in existence.”

All the thrones in Germany were, in truth, being shaken, though they were all eventually to recover; and now the privileges of the Austrian throne itself were being challenged:—

“Kossuth has moved a resolution which the Chamber of Deputies has approved. These people actually demand nothing less than a Constitution for Austria!... The agitation is general, and the terror is great. People are so alarmed—especially the great financiers—that they propose concessions to the popular demand, and see no chance of safety except in making them. One would say that Hell had broken loose. God alone can dam the torrent which threatens to swallow up everything.”

At first, the trouble was confined to Hungary; but the contagion spread:—

“Here, too, the public is very much disposed to ask for a Constitution, and our various provincial assemblies are beginning to pass the most regrettable resolutions. May God enlighten us and give us the strength to be firm! That is all that I pray for.”

And then:—

[41]

“The news from Germany gets worse and worse. There no longer is any Germany in the true sense of the word, for all the German sovereigns have been compelled to make concessions.... One really needs superhuman moral force to withstand this popular agitation.”

So the trouble came nearer and nearer; and it became clear that Metternich himself was the object of popular hostility. Threatening letters were received. A piece of paper was found affixed to Metternich’s door, bearing the words: “Down with Metternich. We want concessions!” Princess Mélanie herself received a significant warning, at one of her own receptions, from Félicie Esterhazy:—

“She let fall the following laconic remark: ‘Is it true that you are going away to-morrow?’ ‘Why?’ I asked her. ‘Because we were told that we had better buy candles in order to be able to illuminate to-morrow, as a great event was about to happen.’”

A great event did happen on the morrow—though not the event which Félicie Esterhazy had in view; and Princess Mélanie witnessed it. She saw a demonstration on the Ballplatz, and heard an agitator, lifted on to the shoulders of his companions, shouting:—

“Long live the imperial house! We want concessions in conformity with the spirit of the times (cheers). Give us freedom of the press (cheers); let justice be administered publicly (cheers); let there be freedom of thought (cheers)! Let those[42] who have outlived their usefulness resign and go (tremendous acclamations)!”

And Princess Mélanie complains that “no one interfered with this indecent demonstration,” and that “no one attempted to silence the brawlers.”

She called the demonstrations “indecent” because they were obviously aimed at her husband, who, far more than the Emperor, symbolised that ancien régime which the students and artisans were resolved to end. The Emperor, indeed, was merely a weak-minded, good-natured old gentleman to whom no one wished any harm. He was as ready to grant concessions as to give alms; and his subjects knew it, cheered him when he drove through the streets, and decorated their barricades with his portraits. Their objection was not to him, but to his police, who took Princess Mélanie’s old-fashioned view of concessions: notably, therefore, to Metternich, the policeman of genius.

It was idle for Metternich to protest, as he sometimes did, in after years, that, though he might sometimes have governed Europe, he certainly had never governed Austria. The people knew—or thought that they knew—better. The chief article in their simple creed was that Metternich must go; and the sole question for Ferdinand and his Court and Ministers was whether Metternich should or should not be thrown overboard as a Jonah who brought ill luck to the Austrian ship of state. The upshot appears from these entries in Princess Mélanie’s Journal:—

[43]

“At half-past six, Clement was sent for to the Palace.”

“Yes, Clement has resigned.”

The circumstances of the interview in which he did so were afterwards related by him to Hübner:—