Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

MRS. RONAN'S GRIEF AT HER SON'S LOSS.

Frontispiece.

OR,

Tom's Three Months in London.

BY

EMMA LESLIE

Author of "The Magic Runes," "The Making of a Hero,"

"The Pride of Greenwich," etc., etc.

LONDON:

THE SUNDAY SCHOOL UNION

57 AND 59, LUDGATE HILL, E.C.

BUTLER & TANNER

THE SELWOOD PRINTING WORKS

FROME, AND LONDON.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER

VII. THE WAY OF TRANSGRESSORS IS HARD

A DANGEROUS FRIEND

TOM'S HOME.

"A LETTER from Uncle George," and the speaker, a boy about fourteen, ran up the garden path, shouting the news as he came.

A brother and sister met him at the door of the cottage, each eager to see the letter, but he held it high above their heads, and as he was taller than either of them, it was quite out of their reach.

"How do you know it is from Uncle George?" asked his sister.

"How do I know, Polly? Why I've been down to the forge, and the postman gave this to father as he went back to work this afternoon."

Tom's father was the village blacksmith, a steady, hard-working man, who always had as much business as he could get through for the neighbouring farmers, but was ambitious for his eldest son Tom to be something better than a blacksmith.

So he had written to his brother in London, telling him what a fine scholar Tom was, and how they had sent him to the grammar school in the neighbouring town, in the hope that he might be able to get some employment in London, as he was altogether too clever for a mere village blacksmith.

His brother's first reply to this had not been encouraging, but a second letter had been sent at his wife's earnest request, and this was the reply to it.

Tom knew all about what it contained, but he would not tell the news until his mother had seen the letter, and he ran with it to find her. She was busy washing, but she took her hands out of the soapsuds and wiped them carefully when she heard about the letter, for she was most anxious for Tom to go to London and get a place in an office, where he might by-and-by rise to be a clerk, as his uncle had done.

Tom stood and rubbed his hands as his mother read the letter, for he knew she would feel pleased at the news it contained.

"What do you think of it, mother?" he asked at last, for he could not wait until she had finished reading it.

"Why you ought to be very much obliged to Uncle George for the trouble he has taken for you. Dick there, will never get such a chance, I am afraid."

Dick had followed Tom to the wash-house, and now looked eagerly from his brother to the letter in his mother's hand; but he did not ask the question that was on his lips.

Polly, however, was always quicker than Dick, and she said, "Is Tom really going to London, mother?"

"Of course I am; didn't I tell you so last week?"

"But you didn't know it last week," retorted his sister; "the letter has only just come, so how could you know it last week?"

"Hold your tongue, and let me think for a minute how I am going to manage," said her mother. "Uncle George says he wants you to go next week, but I am not sure that I can get your things ready, Tom," she said, in a tone of perplexity.

"Oh, mother, you must," replied the boy. "I don't want much; boys don't want a lot of new frocks, like girls."

"But they wear out their shirts too fast," put in Polly.

"Yes, you must sit down to your sewing at once, Polly, and finish that shirt you are making for Tom. And I shall have to clear up my washing as quick as I can and come and see after his other things, for there is no time to spare if he is to go away next week; and I suppose he must if this place Uncle George has got for him is vacant."

"Oh, yes, mother, I must go, of course," said Tom imperatively.

"I shall be obliged to have a lot of new things, I expect," he said confidentially to his sister, as he went back to the comfortable kitchen, where she had begun to set the tea things in readiness for her father's return.

"Yes, I suppose you will have heaps of new things; but father don't seem to think Dick ever wants anything," said Polly in a resentful tone.

Dick was her favourite brother, and she was always ready to take up the cudgels in his defence, for he was a quiet, silent boy, and people were apt to think he was stupid, as he was so much slower in his methods than his brother. But Polly knew Dick better than anybody else, and she would sometimes say when she was angry at her favourite being passed over for his more brilliant brother, "Dick is worth a dozen of Tom, and you'll all find it out some day."

Now she felt annoyed about this project of sending Tom to London; she knew exactly how it would be. The money that had been put aside to buy a new great-coat for Dick this winter would all be spent on Tom, and poor Dick would have to go without or have Tom's mended up to serve him for best, though it was so torn and shabby that its owner had cast it aside as beneath his notice now; for since he had been to the grammar school in the town, he had taken up notions about his dress that had not been thought of before.

When the blacksmith came home from work his wife met him with a pleasant smile, but her first words convinced Polly that Dick would not get his new coat, for her mother said, "It is lucky we put something away for the children's new clothes."

"It was to buy Dick a new great-coat," said Polly; "you said he should have it when Tom had his new suit a little while ago."

"Let Dick speak for himself, Polly," said her father, smiling at her evident indignation.

"But you know he never does speak up for himself, father," said the girl; "and I think it's too bad to take all his money to spend on Tom, just because he is going to London. Why should he have the best of everything and Dick go without?"

"Be quiet, Polly, and let Dick speak for himself," said her mother.

But she would have been very much surprised if the boy did speak up for himself, for this was not at all in his way, and it would have vexed her, too, just now, for she had made up her mind that all the money laid aside would have to be spent upon Tom before he went to London.

She had already turned over in her mind what things he must have, and she said to her husband, "We must go and get him some new trousers and boots to-morrow, and I should like him to have a new coat, too, if you can spare the money."

"He can do without the coat for the present," replied Flowers, as he sat down to the table and helped himself to bread and butter.

Tom frowned and looked at his mother, and then down at the jacket he was wearing. "This will do for Dick when I have done with it," he said, "I shan't want to take this with me."

"Why not?" asked his father. "That will do for you to wear at first, till we see how you are likely to get on, and then—"

"Perhaps you won't like it, and will want to come home again," put in Polly mischievously.

"That's a girl's notion," said Tom scornfully. "Of course you would cry for your mother before a week was over, but boys are different."

"What do you know about it? You have never been away from home in your life, so how can you tell?" retorted his sister.

"Now, don't begin quarrelling, Polly," said her father. "Tom won't be at home much longer, so try and be civil to each other while you are together. I think you had better go with me to the tailor's in the morning, my boy, for I daresay your mother has enough to do to get your shirts and such things ready, and I shall be able to spare an hour or two to-morrow. When the tea things are cleared away, you had better sit down and write a letter to your uncle, and I will put a note in for myself; but you must thank him for taking all this trouble for you, and tell him you will be at Paddington Station next Wednesday evening as he wishes."

So when Polly had put the tea things away, Tom brought out pen and ink to write to his uncle, while his mother sat down to finish the shirt she had been making for him.

It was quite an event, not only to the family, but to the whole village, for Tom and all the family were born in the place, and his father and mother only came from the next village when they were married. And so to hear that Tom was going to London to live with his Uncle George, and settle down there, caused quite a stir among the neighbours, and every boy in the place envied him his good luck, and wished they had his chances of getting on in the world.

On all sides the blacksmith and his wife were congratulated on Tom's prospects, for he was going to live with his uncle who had no children of his own, and therefore could well afford to look after his nephew.

The rest of the week was busy enough, not only for Polly and her mother, but Dick was pressed into the service too, for none could do enough for the boy who was so soon going away to the world of London.

Dick did not mind having to wear Tom's old coat, instead of having a new one, as by this means his brother could have an entire new suit for best, and only Polly grudged everything of the best being given up to Tom, but she did not say much about it after the first evening was over.

So Tom went to London provided with everything that loving hands could think of for his comfort, and the village was proud of the tall, handsome boy who went away in the carrier's cart early in the morning, that he might be in good time for the train that left the town about ten o'clock.

The situation which had been secured for Tom was in a City warehouse, where there was a number of lads about his own age, or a year or two older. Here he had to write invoices, direct envelopes, run errands occasionally, and make himself generally useful, both in the warehouse and office.

He was to live at his uncle's house, but he felt a little disappointed in his aunt, for she was not a bit like his mother, and seemed to think it was a great bother to have a boy about the place.

His uncle took him to the warehouse the morning after his arrival, and Tom found he would have to take his dinner, for it was quite two miles from where his uncle lived to the City. The noise and confusion of so many people passing and re-passing almost bewildered him at first, and then the wagons and omnibuses seemed as though they would never give him a chance to cross the road. But he was not a boy to be easily conquered, and his uncle assured him he would soon get used to it all, and think nothing of it.

He explained which way he was to take when he came home in the afternoon, as they went along, for he would not be going back at the same time, and having made this clear, he took him in to the gentleman at the warehouse, and there left him.

Tom found that there were several other lads about his own age employed about the place, and at dinner time he went out with the rest to eat the meal he had brought with him. They had an hour to do as they pleased, and he was not sorry when one of his companions proposed that they should go for a walk. Tom knew nothing of the neighbourhood, and was glad enough to have someone of his own age who was willing to show him some of the wonders of London. And he at once began to ask the boy about the Tower, and the Bank, and Westminster Abbey, and other places he had read about at home.

"We can see the Bank as we go home," replied his new friend; "but you'll have to wait to see the other places. Do you go to Sunday-school?" he asked.

Tom shrugged his shoulders. "I had enough of Sunday-school at home," he said; "I shan't go if I can help it now I've come to London. I want to see all I can, not to be moped up in a Sunday-school all the time."

"But you ain't moped up all the time," returned the other. "I was going to ask you to come to my Bible-class on Sunday afternoon, and then you could join our social club for the other evenings in the week."

"What? Sunday-school all the week! No, thank you—I've had enough of school, and I shouldn't have thought you London chaps would have thought so much of it as to go week-day and Sunday too. I want to see what London's like when my work is done, not pen myself up—"

"Oh, but we don't pen ourselves up," interrupted his new friend. "We meet at the schoolroom twice a week and play at draughts or chess, and then the other evenings there are classes for writing, and reading, and arithmetic, and—"

"Oh, I've had enough of that too," said Tom, in a rather contemptuous tone. "I want to go about and see things. I could play draughts in the country."

"To be sure you could," chimed in another lad at this point. He had been walking with them, but had not spoken before. "Bob is so gone on Sunday-schools, that he is afraid to have a game for fear his teacher should hear of it; ain't you, now?" he said, appealing to his companion for confirmation of this.

"I don't care about pitch-and-toss, that you and Simmons think so much of," admitted Bob.

"There! I told you so. He won't play at pitch-and-toss because it's a bit lively."

"No, it ain't that. I like lively games as much as you do, but that is too much like betting, and I promised I wouldn't bet or—"

"What is betting, then?" asked Tom.

"Don't you know? Just come up Fleet Street, and you shall see."

"We haven't got time," put in Bob. "We shall catch it if we're late, you know."

"Oh, all right; I know what I'm about, and so does this chap, though he has just come up from the country. You come with me, and if Bob likes to go back, why I can show you the way just as well as he can—you come to Fleet Street with me."

So Tom left his first companion.

And as soon as they were left to themselves, he confided to Tom that he was very anxious to go and find out what horse had won in a race that was to take place that day at Newmarket.

"Don't let it out to Bob, for he is such a muff about his Sunday-school, but I hope to win six shillings over this race," said the other as they hurried up Fleet Street.

They had not gone very far when they were stopped by a crowd that was gathered round a shop window. And as they reached it, his companion said, "Here we are. The news will be out in a minute, I expect," and then he tried to elbow his way to the front, closely followed by Tom, who was afraid of missing his new friend in the midst of this crowded street here in London.

Still he could not understand, if the race was to be run at Newmarket, why they should all stand staring up at this shop as though their lives depended upon what was to be seen.

At last with a muttered grumble, his companion said, "We must go now, and look sharp about it too, or Phillips will be in a wax and fine us for being late. Come on," he added, pushing his way through the crowd which now nearly blocked the footpath.

As soon as he was clear of it, the boy took to his heels and ran and dodged between the people in such a fashion that Tom could scarcely keep him in sight, and nearly got run over trying to dash across the road after him.

As it was they were both beyond the time when they ought to have got back to their work, and were spoken to very sharply for it.

"This is a bad beginning, my man," said one of the older clerks as Tom went panting to his desk. "I thought you told me you had brought your dinner with you."

"Yes, sir, I did, but I went out for a walk afterwards, and, and—" somehow he did not like to say anything about Newmarket Races for fear his new friend should not like it, so he added, "we looked in a shop window too long."

"So I should think," said the man with a smile. "You must be careful not to be late when you go out for a walk at dinner time or you will get into trouble over it."

No more was said and Tom went on with his work, but he made up his mind when he went to Fleet Street again, not to stay so long.

At the close of the day when he was leaving the warehouse, his new friend met him on the steps.

"Have you heard the news?" he said, in an excited tone, but speaking very cautiously.

"What news?" asked Tom, thinking he ought to be as eager as his friend.

"Why Drizzle's won, and I had a lot of money on him."

Tom stared. He had not heard enough of horse-racing to understand all at once what his friend meant, but he did not leave him long in ignorance as to his meaning.

"Jenkins went out in the afternoon, and he told me if he got a chance, he should run and find out who was the winner, for he had put every penny he could scrape up on Featherhead. I told him it was a roarer, for I got my tip from a man I heard talking in the train. He was one of the knowing ones he was, bound to know the correct card, don't you see, so when I heard him say he should back Drizzle for all he could put on her, I made up my mind to do the same. Jenkins says she came in first, so I stand to win six shillings, I reckon—and that only cost me sixpence, my boy."

Tom opened his eyes, and looked at his companion. "Six shillings! What, a whole week's wages to do as you like with?" uttered Tom.

"That's just it, my boy. I put my sixpence pocket-money on Drizzle, and I've got six shillings for it. Isn't that a lot of money for you?" he demanded, rubbing his hands with glee. "Jenkins ain't up in the clouds though over it, I can tell you; he made so sure Featherhead was coming in first, that he borrowed Harry Bowers' allowance, and stood to win more than me. But no, bless you, Featherhead was nowhere, and so his money's gone, and he looks awfully down about it."

"Where are you going? I thought you said you lived my way?" said Tom, suddenly stopping, for he could tell they were not going in the direction his uncle had told him to take when he left him in the morning.

"Why, I'm going to make sure about Drizzle, first thing. Come on, we shan't be long, and then we can walk home together," and the boy slipped his arm in Tom's and drew him in the direction of Fleet Street, which they very soon reached, and then elbowed their way to the spot where they had stood at dinner time, for there was still a crowd round the window, many like Tom's friend, wishing to make sure before they went home whether they had lost or won their money.

"Yes, it's all right," he said at length; "I shall get this money sure enough. I say, you've brought me luck, old fellow, and if you like, I'll lend you sixpence to put on the next race."

"But I don't know anything about horses, except their shoes," said Tom laughing.

"Oh, that don't matter, we'll go partners, if you like. I'll tell you what horse to put your money on," said his companion.

"Thank you, I'm much obliged, but I don't think I'll begin just yet; I haven't got used to London ways, and—"

"Oh, you'll soon know your way about, I know. I can tell. You were not born on a Thursday, I can see."

Tom knew this was intended as a compliment, and laughed. "If I do come from the country, I know what I'm about, I hope. I tell you, country lads are not such fools as people take them to be," added Tom, nodding his head sagaciously.

"Well, you ain't, that's a sure fact. I could see we should be chums as soon as you came in this morning."

He felt on good terms with all the world, since Drizzle had won the race and changed his sixpence into six shillings, but how it would have been if he had lost, he did not say or think. He was too much elated over his luck to think of that just now.

The boys walked the first mile of their journey homeward together, and then their roads separated, but they agreed to meet again in the morning and walk to their work.

BEGUILED.

TOM met his new friend the next morning, who was still in very high spirits over his good fortune, and offered to show Tom where to go to spend an evening merrily. But this offer Tom declined, for he had promised his mother before leaving home that he would take care to go back to his aunt as soon as his work was over, and he meant to keep his word—at least, until he knew more about London than he did at present.

He took care not to go to Fleet Street again at dinner time for fear he should be late, for his uncle had warned him about this when he heard where he had been. But Randall did not press him to go again, they had their dinner and strolled out for a little while, Randall showing him St. Paul's Cathedral, and pointing out the General Post Office, and several other large buildings.

In this way the lads grew more intimate, and when they went home together in the evening, Randall showed him the six shillings he had won on Drizzle. Of course, Tom wished he could win some money as easily, and Randall promised to tell him when he heard of a good thing.

"Mind you, I don't do as some fellows do," went on the boy, "put money on every race they hear of, I just wait till I can find out about a horse, and then I plank my money down upon it."

But Tom began to get tired of the horsey talk and Randall's wisdom before they parted, for he would have liked to talk about Dick and his home, if he could only have found some one to listen to his story.

His aunt's house seemed very lonely to him; not at all like the pleasant home he had been used to all his life. His uncle did not get home until late in the evening, and his aunt, who was not used to boys, sat and watched him for fear he should scrape his feet on the chair-rails, or push it when he moved instead of lifting it, and so wear out the carpet, for they had tea in the little back parlour, and she was very careful of the furniture, lest it should be spoiled.

"Hadn't you better go to bed now?" she would say to Tom about eight o'clock.

And Tom went; but he did not like it much, though it was dull to sit and watch his aunt at her sewing, or tease the cat, which seemed all the amusement he could find. He was not very fond of reading, and if he had been, there were no books about here for him to read, so he went to bed at eight o'clock the first week of his stay.

But when he had been there a fortnight, and had learned his way about the neighbouring streets and roads, he thought he might as well go out for a walk after tea, as sit and look at his aunt, and his proposal to do this seemed rather to please her.

"Yes, you can go out for an hour, if you like, only don't lose yourself, and mind you get home before your uncle comes in."

"All right," said Tom, smiling at the idea of losing himself now, for he had taken careful note of the different turnings, and as his uncle rarely got home before ten o'clock, there would be plenty of time for him to go for a long walk.

The street where his aunt lived opened into a broad, busy road with large, well-lighted shops, and of course Tom made his way there at once, sticking his hands in his pockets, for the evenings were chilly. When he got there he was at a loss which way to turn, for although he knew the road leading to the City, he did not want to go that way now, but to vary his walk if he could. So he stood at the corner looking up and down the street, undecided which way to take, when a lad about his own age came sauntering towards him.

"Fine night," he remarked, as he halted beside Tom. "Are you out for a stroll?"

"Yes, I came out for a walk, but I hardly know which way to go," replied Tom, looking at the stranger to see if he had ever spoken to him before.

He did not recognise him, but he looked a respectable lad, and so, when he proposed they should go along the road together, Tom cheerfully assented, for any company was better than none, he thought.

"Beastly place London is," said his new friend when they had exchanged a few words, in which he detected that Tom had recently come from the country.

"Don't you like it?" asked Tom, in some surprise, for this long row of lighted shops, and the pleasant bustle of the street was almost like fairyland to him.

His new friend made a wry face, but did not reply immediately to his question.

"Things are pretty dull here sometimes, and there is no friendliness among people like there is in the country. You look at your neighbour as though he was a wild beast bent upon eating you up, and so you are afraid to speak to him."

Tom laughed. "I don't think I am much afraid of strangers," he said, "or I should not be walking with you."

"Ah! That just shows you have not been here long enough to get spoiled. I knew at once by the friendly look in your face that you had not been here long. Come up to get a place in some office, I suppose?" said his new friend, looking at him curiously.

"I have got a place," replied Tom. "My uncle has lived in London for years and years, and he got me a place, and I live with him."

His companion gave a prolonged whistle. "I wonder he hadn't told you never to talk to strangers when you came out for a walk," he said.

"He doesn't know I am out," replied Tom. "I'm not a baby, either, that is likely to lose its way, so aunt said I might come out for an hour if I liked."

"Sensible old lady, I am much obliged to her, for I wanted a companion for a walk, and so I am glad to meet you. Two country chaps like us ought to be friends, you know."

"Yes, of course," said Tom, glad to meet with a friend from the country. "What part of the country do you come from?" he asked the next minute.

"Well, I was at Newmarket last," said his new friend.

"Newmarket," repeated Tom; "why, that is where they have horse-racing, isn't it?"

"What do you know about horse-racing?" said the other quickly. "I thought you said you had only been in London a fortnight."

"Isn't that long enough to learn about it?" said Tom, who was determined not to let this lad think he was altogether ignorant of London life and ways. "Perhaps you think I don't know that Drizzle won the race there about a fortnight ago," he added with a knowing nod, and thrusting his hands deeper into his pockets.

His companion was certainly surprised, and looked it as he said, "Well, you haven't been long learning the ropes, certainly. What did you put on Drizzle?" he asked.

"Nothing; but a friend of mine turned in a nice little bit." He would not mention the amount, for he had an idea that this new friend would not regard six shillings as an overwhelming fortune.

"Well, look here, don't you venture to put money on a horse like Drizzle," said his companion oracularly. "If some of the others had not been pulled, she would have come in last instead of first, and then where would your money have been?" he asked in a tone of triumph, which seemed to imply that he knew more about such matters than Tom could tell him.

Tom looked puzzled, but at last he said, "Of course, if you have lived at Newmarket, you know all about it."

"I hope I know better than to put money on a horse like Drizzle," said the other in a tone of contempt.

"Where do you work?" asked Tom, thinking he ought to take Randall to see this friend who knew so much about horses.

"Well, I'm not doing any regular work just now. Can't get anything to suit me exactly. But then I need not be in a hurry for a time, you see."

"Then you don't go to the City every day?" said Tom.

"No, not every day. I go sometimes, of course, and I could meet you there now and then, if you liked."

Tom supposed his new friend was staying with relatives, and rather envied him. They walked about together for an hour or two, and then Tom said he must go home. His companion pressed him to stay longer, but Tom said he must go, although he was rather loth to part with such an entertaining companion.

The talk about horses had branched off into talk about cards, and Tom's amazement was great when he found that his new friend could tell him all about the games that were generally played, and when he assured him that money was often made on cards, especially if anybody knew the games well.

He went home at last thoroughly impressed with his new friend's wisdom, and thinking how lucky he was to have met him. He had promised to meet him again the following evening, and he went home in high spirits, thinking what he should have to tell Randall and Bob when he met them in the morning. It was nearly nine o'clock when he got home, but his aunt did not say anything about the time, only told him to get a piece of bread out of the cupboard, and eat it in the kitchen, if he wanted any supper.

Tom took the bread, for he was hungry, but he did not care much about it, for there was always plenty of home-made jam or honey from their own hives at home, and to eat dry bread for any meal had been looked upon as a punishment, and, besides, he thought his aunt might have given a bit of cheese with the bread.

But he did not say anything about it, he ate it and went to bed to dream of horses and his new friend.

He told Randall about Drizzle being a roarer, and how nearly he had lost his money; but he did not seem as much impressed as Tom expected to see him.

"You always have to take risks, of course," he said loftily; "and I should mind what I was about with a fellow you know nothing of."

Tom laughed, for Randall's words and manner so exactly bore out what his new friend said about London boys, that he felt rather glad he was above such narrow prejudices and suspicions. "I wasn't born on a Thursday," he said, quoting his own proverb.

"Thursday or Friday, you'd better look out," said Randall.

"You don't like your favourite horse being called a roarer."

"Oh, bother the horse; Drizzle can take care of himself, if you can," said the other. He felt rather nettled that Tom should presume to give him advice upon this matter, and for the next day or two they were rather cool to each other.

But Tom continued to meet his new friend after tea, and they generally went for a long walk together. The time of Tom's return home getting a few minutes later each night, until at last his uncle got home first, and the clock had struck ten before he knocked at the door.

Of course his uncle wanted to know where he had been, and who he had spent the evening with, but to his own surprise, Tom could tell very little concerning his companion. He had been told to call him Jack, but he did not know where he lived; and so far as he knew he did not do any work, so that his uncle's questions revealed to him the fact that while he had given his new friend every scrap of information about himself and his home, and his employers, he really knew nothing of him beyond the fact that his name was Jack, that he was a pleasant spoken lad, and seemed to have plenty of money to spend, for he generally bought cakes for Tom and himself during the evening.

All this was told to Mr. Flowers when he pressed Tom with questions, but as there seemed to be no occasion for forbidding the acquaintance, his uncle only warned him to be careful and not to stay out after nine o'clock at night.

Perhaps if he had enquired a little further, and asked what they found to talk about, he might not have been so easy about the matter. For this new friend of Tom's had succeeded in making him believe that there was more than one short but to making money, if he could only discover it; as though to make money and not to give honest work and service was the whole end for which a man or boy had to work.

Tom had often heard his father speak of putting good work into whatever job he did, but he did not see that there was any connection between putting a horse-shoe on safely and securely, and doing such work as he had to do at the warehouse. And the talk with his friend Jack had given him the impression that in London to be sharp and look out for "Number One" was a good deal better than plodding work.

With this had come a desire for more spending money. His wages were but six shillings a week, which he took home to his aunt every Friday, and from which she gave him threepence for himself, but out of this he had to buy his own boot and shoelaces.

Threepence a week had seemed a large sum to him at first, but since he had become acquainted with Jack, who spent more than that every evening, it had seemed very small, especially as he sometimes had to spend half of it in replacing broken boot-laces.

As it was, he could very seldom produce a penny for the nightly consumption of cakes, and as Jack was too good-natured to eat and see him go without, he found money for both, remarking, when Tom protested against this arrangement, that he should stand treat by-and-by when he was in luck, as he would certainly be before long.

In Tom's first letters home, when he knew that he was to have threepence a week, he had written to tell Dick that he meant to send him something from London at Christmas. But now he had been here three months and Christmas was drawing near, Tom wanted money for himself, and there seemed little chance of Dick getting his promised present.

The luck promised by Jack had not come to him, although he heard every now and then of one and another among his companions at the office doubling or trebling their week's pocket-money in a few minutes. Sometimes it was at card-playing, sometimes on a game of pitch-and-toss, for it seemed that when they could not gamble on horse-racing, the lads found out another way of betting.

But Tom never seemed to have money enough to risk in this way, and he was complaining of this to his bosom friend Jack one day, when he offered to lend him five shillings for a month, if he liked to accept it.

"You have brought me luck, if you haven't had it yourself," he said laughing, "so it's only fair you should share in it."

But Tom would not borrow if he could help it, he shook his head rather sadly, though, as he thought of a letter that had just come from his sister Polly, suggesting that he should send Dick a pair of warm gloves, as he had very bad chilblains on his hands this winter.

"Bother his chilblains," said Tom, half aloud, as he read the letter one morning at breakfast time.

"What is that, Tom?" asked his uncle looking across the table.

"Dick has got bad chilblains this winter, and Polly wants me to send him a pair of warm gloves."

"Aye, to be sure, for the Christmas present you were talking about a little while ago, when you first came up; couldn't be anything better, they won't cost much; can easily be sent by parcels post, and will be very useful, too. I tell you what, my boy, I will get them for you. I have got a friend in the trade who can get me a pair at first hand, so that they will not cost you so much, for I know you have not much money to spare for them."

"No, uncle," said Tom, looking down at his bread and butter, and not caring to say more, for, in truth, he did not know where the money was to come from to buy these gloves, although he had talked a good deal about the Christmas presents he was going to send home when he first came to London.

Now, as he thought over the matter walking to the City, he wondered how he was to get the money to pay for these gloves, and while he was thinking of it, his uncle said:

"I think I can get you a first-rate pair of lined leather gloves for Dick for about eighteenpence something that will make them open their eyes at home when they see them, and give Master Dick something to remember as his first pair of gloves. Of course you would like him to have something good coming from London?"

"Yes, uncle," answered Tom, not knowing what else to say, but wondering silently where he was to get eighteenpence.

His uncle, however, did not seem to notice his silence. He took all the talking upon himself that morning, for he was in good spirits, and glad to have a listener. It was not often that they went to the City together now, for Tom generally met Randall and Bob, and walked with them, but his uncle had to go earlier that day, and that was how it was they came to be walking together.

They separated, however, before the warehouse was reached, and Randall overtook him before he got in.

"I say, what made you come on without me?" he asked. "I wanted to see you this morning. Don't you know I said I should want that twopence I lent you last week?"

"All right, you shall have it," said Tom, in an irritable tone, for he felt as anxious and worried over his small debts and liabilities as a millionaire would over the threatened loss of all he possessed.

He reckoned up what he owed to one and the other now, for Randall was not his only creditor, though his debts were mainly debts of honour, and represented the wild efforts he had made to realise something of the dazzling prospect held before him by his new friend, of how money could be made by a sharp lad when he once knew the ropes.

"The ropes" he had been trying, by which he hoped to make a little money to spend when he went out in the evening, was the game of pitch-and-toss. It was usually played at dinner time among a number of the lads employed at the different warehouses round.

They managed to meet in a quiet corner out of sight of the police or the older men, and there one would throw up a halfpenny or penny, and the rest bet eagerly on which side came uppermost.

Tom had seen Bob and another lad win sixpence or eightpence in the course of a dinner hour, and at last he thought he would try his luck. But in spite of all Jack professed to know about a lucky hand, he invariably lost all he risked, and then he had ventured upon the desperate plan of borrowing a penny or two from whoever would lend, for once the gambling spirit had seized hold of him he could not shake it off.

He had threepence in his pocket to-day, and he was so impatient for the dinner hour to come round, that he could not give the proper attention to the work in hand, and made several mistakes, which brought down upon him the anger of the foreman, who even threatened to have him dismissed if he was not more careful.

When at last the dinner hour arrived and the lads were free to meet in their favourite haunt, Tom pressed forward to join in the game—not for the sake of the fun and excitement, that period was over for him just now, and the deadly thirst for gain had taken its place.

He staked only a penny first and won twopence. This elated him, and he staked the twopence and won fourpence, and by the time the bell rang for them to go back to work he had tenpence in his pocket, besides having paid Randall the twopence he owed him.

It was with supreme satisfaction that he went back to his work rattling the halfpence he had won. He could afford to think of Dick's gloves now with something like pleasure, for it must be that his luck had turned at last, as Jack had always said it would. And a day or two of winning steadily would not only give him all he wanted for the gloves, but quite set him up in pocket-money for the Christmas holiday.

So when he met his uncle at breakfast the next morning he asked if he had enquired about Dick's gloves, and asked him how much they would be. "Just about what I thought, my boy. Brown tells me he can get me a tidy pair for eighteenpence."

"But Tom won't have saved eighteenpence by Christmas," said his aunt, who happened to be present, and who had no notion of her husband buying these out of his own pocket. "Tom can't save a penny," she added, in a reproachful tone.

For answer Tom took the halfpence out of his pocket that he had won the day before, and laid them down upon the table before his aunt, to the great amusement of his uncle.

"Well done, my lad," he said, with a mischievous glance at his wife.

"Where did you get all that?" she said, rather tartly. "You told me the other day it cost you such a lot for boot-laces, you never saved more than a penny a week."

Tom coloured furiously, and wished he had not grumbled over the bad laces; but he knew his aunt's eyes were upon him, and that he was expected to give some reason for the possession of all this money, and he was not long finding one. He had once been sent to fetch a dinner from the eating-house close by for one of the clerks who did not wish to go out, and for this service he had been paid twopence, and this was brought forward now as though it was a matter of frequent occurrence, and that twopences were often earned in this way.

"Then you ought to have said so before," retorted his aunt, in a reproachful tone, "for if you can get halfpence so easily, I don't see why I should give you threepence a week for nothing."

"Oh, nonsense, Maria," said her husband, "it isn't often the boy can earn so much extra. Mind you take care of it," he added, as he rose from the breakfast table, and there the matter ended for the present.

WAS HE A THIEF?

DURING this time Bob Ronan, the lad with whom he had first made acquaintance, had been gradually drawn into engaging in the very games he had at first denounced. He, like Tom, had not long left school, but he had no intention of leaving Sunday-school when he went to work in the City, and endeavoured to persuade Randall first, and afterwards Tom, to join him at the Sunday-school, as they did not live so very far apart but that they could have done this if they had felt so disposed.

But the laugh that was raised against him whenever he ventured to mention the Sunday-school was at last too much for him.

Boys can endure anything better than ridicule, and Tom and Randall had both taken to ridicule his love for his Sunday-school.

If he had only "dared to be a Daniel," and borne this without flinching, and still held firmly on in his own way, he might have helped to keep his companions from doing wrong, but instead of this, like a foolish lad, he gave up going to Sunday-school himself, telling his mother that he was getting too old to go now.

When this was done, it was easy for Randall to persuade him to join in the game of pitch-and-toss, which he had formerly denounced, and so he, as well as Tom, had become involved in the meshes of this pernicious game, and were always eager to win that they might have more money at command.

Just now Bob was anxiously saving every farthing towards buying a warm winter shawl for his mother.

They were poorer than Tom's friends, for Bob had no father, and had been wholly dependent upon his mother's earnings as long as he could remember; so that it had been necessary for him to leave school as soon as he could, to help to maintain himself. But his mother had been very anxious that he should continue at the Sunday-school and week-night classes, and when Bob declared he could not go any longer, it had been a great grief to her.

But she was afraid to say too much about it, for fear of driving her boy further away from her, but she prayed and waited, hoping that something would happen to send her boy back to this shelter and safeguard, for she felt that as he had no father to guide and direct him, he had all the more need of such counsel as his Sunday-school teacher was ready to give.

But while his mother was thinking thus, Bob was wondering how he could make more money, and Tom's thoughts were occupied over the same problem when he met his friend Jack one evening as usual.

Jack was greatly excited over some news, or at least he appeared to be, and Tom had the most profound faith in his friend, and believed everything he said.

"I've learned a thing or two about a horse lately that will help us to make some money, if we can only get a few shillings together to lay on it," he said as they walked together down the road.

Tom looked at his friend. "You can easily do that, I suppose," he said, for Jack always seemed to have plenty of money to spend.

But he shook his head slowly now. "That's just where it is," he said with a sigh, "now I see a sure chance of making a little money, I haven't got a shilling left to do it with."

They walked on in silence for a minute or two, and then Jack said, "How much money could you put your hands on, do you think?"

"I might manage a shilling," said Tom, thinking of the money he had got for Dick's gloves, and that he might surely count on winning another twopence at pitch-and-toss the next day.

"A shilling," repeated Jack in a somewhat contemptuous tone; "that isn't much good. We must have more than that."

"I hope Warrior will win, because my friend Ronan has put all his money on it," said Tom, ignoring this remark.

"Well, I can tell you Warrior won't win; but mind, you mustn't say anything about it, or else I shall get into trouble. And now, what about our chances? A shilling ain't much good, but ten more would do for both of us, and I want you to lend me something to put on this race. Couldn't you borrow ten shillings for a day or two?" said Jack, and as he spoke he cast a meaning look at Tom.

But the lad did not see this in the dusk. "Who do you think I could borrow ten shillings of?" he asked, in a tone of surprise.

Jack shook his head. "I'm stumped," he said, "but I thought you might manage to get something for yourself and me too; we both want money badly enough, and it would be even, for as I can tell you how to make every shilling into ten, why I thought you could surely borrow half-a-sovereign or a sovereign for a day or two, that we might go shares with. Why it 'ud set us up for a week or two, if we could clear a few shillings on the horse that is going to win. It isn't as though there was any chance about this, it's just a dead certainty and no mistake, and, I tell you, twenty to one is her price now, and she's bound to win."

"What is the horse's name that is sure to win?" asked Tom, in a meditative tone.

"Ah, that's more than I dare tell, for fear it should leak out. It ain't Warrior though, I can say that much; but mind, you must keep that dark, for everybody has gone on Warrior, and so those of us that can get a peep behind the scenes stand to make a lot of money out of it. Another thing, if I tell you the name of the horse that is bound to bring your money in safe, I shall expect a little commission on the job."

Tom looked as though he did not quite understand his friend. "I thought you were doing this for me, because—"

He was interrupted by a roar of laughter from his companion. "Do you think the railway people let me go down to the country by train because they like me?" he asked.

"Well, no, of course not," answered Tom, who greatly disliked being laughed at. "I didn't suppose the railway people came out here to walk with you every evening, but I do, and so I thought that counted for something."

"It counts for a good deal, my boy, for if we wasn't friends and all that, I shouldn't tell you what I have, for if my governor knew I said a word to you, he would break every bone in my skin."

"Then you will be my friend still?" said Tom.

"Why, of course, and I hope you'll do the friendly by me too, and let me have ten shillings at least by Wednesday night, and a shilling commission for placing your money will make it eleven."

"But where am I to get eleven shillings?" said Tom wistfully.

"We shall stand to win a sovereign a piece if you can only manage it. And there 'll be no waiting for money either, for I shall be able to bring it to you the day after the race," said Jack, quite ignoring what Tom had said.

"If you could only tell me how I am to borrow the money, I would get it fast enough," replied Tom.

"Well, I know how such things often are managed by young fellows who are in offices like you are," and as he spoke Jack looked keenly at his companion to see how he took the suggestion he was about to make. "It isn't as though there was any risk about the matter," he went on. "This tip I have got is a dead certainty, and every two shillings put on the horse will bring in a pound. I said we should stand to win a sovereign a piece—what could I have been thinking about? Why, we shall have five pounds between us! If that ain't a lot of money, tell me what is, and all for eleven shillings down. Why, I know this, if I was to come up to your place and tell some of your fellows what I have told you, why I could have twice eleven shillings, and nothing said about it. Don't you know how the thing is done?"

"No, I don't know where to borrow eleven shillings, or I would do it fast enough," said Tom, ruefully.

"Don't you ever forget to enter money when it comes in?" said Jack, speaking in a lower tone. "You have some money to take, I know."

"How do you know?" said Tom quickly.

"Oh, never mind what a little bird whispered to me about it; but I do know that you take money sometimes, and hand it over before you come away at night. Now it would be easy enough," and then he went on to explain how he could take ten shillings of his master's money and bring it to him for a day or two. "Nobody would ever find it out," said the tempter.

Tom made no reply to this proposal, it was evident he was thinking it over, and the more he thought of it, seeing the proposal had not actually shocked and offended him, the more likely he was to see the reasonableness of it, and so Jack said no more about how the money should be got, but how they should spend what they won.

"We'll go to the theatre and see the pantomime," exclaimed Jack; "if you haven't seen a pantomime you've got a treat in store, I can tell you. Oh! The fairies and the transformation scene, it just beats everything you ever saw in your life; and you'll have enough to tell the country folks about then."

"How much will it cost?" asked Tom, for he had made up his mind to be careful with this money when he got it, so that he was not worried again as he had been lately.

"Oh, not more than we can afford, if we get this money. It all depends upon you, whether we do get it," he added.

"Well, I'll see," said Tom, who could not quite make up his mind to embezzle this money, tempting as the prospect was.

Prudence would whisper, "Suppose the horse should not win," and the thought of the predicament he would then be in, filled him with horror as he thought of it, and he almost made up his mind to have no more to do with Jack or his proposal. For he did feel disappointed when he heard that it was not for pure and simple love of him that his friend had told him what he had, but as a matter of business and by way of repaying himself for the trouble of collecting the information.

If Bob Ronan had only held firm to his principles, instead of giving up the Sunday-school, for fear of being laughed at, he might have been of service to Tom now; might even have persuaded him to join the Sunday and evening classes, for Tom would have been ready to go anywhere away from Jack just now. But the habit of going out in the evening had been formed, and he had nowhere else to go, as it seemed to him.

He wished some of the other lads he knew would propose something that would prevent him from seeing Jack again. He even went so far as to say to Bob, "Do you go to those classes now you were talking about when I first came up?"

"No, I don't," answered Bob a little shortly, for the subject of the Sunday-school was a very sore one to him then.

He was vexed with himself for giving it up, so to be asked about it was not at all pleasant.

"You didn't think much of it, then, after all," said Tom with something of a sneer.

"What do you mean by that?" demanded Bob angrily.

"Why, if you'd thought much of your school, you wouldn't have given it up just because some of us laughed at you. I didn't think you would either," he added wistfully.

If only Bob had known that Tom was ready to catch at this, as a drowning man catches at a straw, to save himself from the temptation that was pressing upon him, he would not have turned away as he did, but would have confessed what was the truth, that he was very sorry he had been so foolish, and together the two boys might have gone that evening to the teacher, and told him that they wanted to join both the Sunday and week-night classes.

Tom would have gone readily enough now if he had only been invited, and the teacher, who was always at the school three evenings a week, would have been glad enough to welcome back the truant Bob, and his new friend as well.

Ah! If they had only gone. If Bob had only had the courage to speak out his thoughts just now, for as he stood talking to Tom, he was wishing he had never left the school, nothing had seemed to go right with him since, and he had such a load of care on his mind that he dare not tell anyone of.

And Tom would have given anything that would have afforded him a chance of not meeting Jack that night. A little friendly talk with one who understood a boy and his difficulties would have saved Tom from committing a crime that he would have to regret as long as he lived.

But the opportunity that might have been seized at dinner time vanished without being improved, and Tom yielded to the temptation.

The next minute he would have been glad to put the money back, for his conscience whispered, "You are a thief." But there was no chance to replace it, for the books were fetched just afterwards, to be looked over by Mr. Phillips, who came to see that he had made no mistakes, and the books and money balanced correctly.

"Very good, Flowers," he said, when he had gone through the day's accounts and found they were quite right. Little did he think that the boy's heightened colour, as he heard this, arose from a feeling of bitter shame and self-reproach. He thought the lad was pleased to be commended and he added, "If there should be a vacancy here at the desk, I will speak for you, my lad, and then I would advise you to go to school in the evening, and learn book-keeping thoroughly."

"Yes, sir," said Tom, in an absent manner.

"You are fond of accounts, I suppose?" said Mr. Phillips, as he finished his scrutiny of the books.

"Yes, sir; it was because I was so fond of doing sums that father sent me to the grammar school in the town for a year, after I left the village school."

"Ah! And he will be pleased to hear you are getting on in London?"

"Yes, sir, he will," replied Tom, feeling quite elated and forgetting the money he had in his pocket.

"Well, now you may tell him we are very satisfied with the way you have done your work, and when there is a chance of a rise you shall have it. But mind, my lad, you must be steady and careful, and not get yourself mixed up with bad company."

"Thank you, sir, I will be careful," replied Tom, thinking he would sit down and write to his father after he got home and tell him all about it.

He knew it would please father and mother too, better than any Christmas present he could send to them, and he had made up his mind to do as Mr. Phillips advised, and be more careful of the company he kept, when once he was out of his present difficulties.

By the time he had put his great-coat on, he had forgotten the money he had in his pocket, and went out with as light a heart as though he were still an honest lad. He had forgotten Jack and the races, and everything else but his father's delight when he got his letter. He knew exactly what would happen, his mother would go the day after it arrived to show it to his aunt and then to the rectory. His aunt was sewing-mistress at the village school, and she would be as proud as his mother when she heard how he was getting on in this great, splendid London.

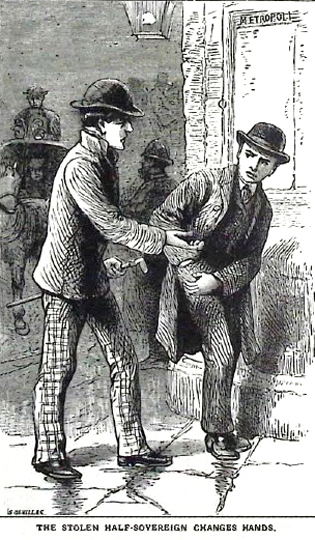

THE STOLEN HALF-SOVEREIGN CHANGES HANDS.

The City was a very beautiful place to Tom just then, and he forgot that there was such a person as Jack, until he came suddenly upon him waiting at the corner of Moorgate Street.

He started and stepped back as he recognized him, and then came the recollection of the money he had in his pocket. "I didn't expect to see you, Jack," he faltered.

"And you don't seem killingly glad now you do see me," replied Jack in something of a huff at his cool reception. "I suppose you have forgotten all about that money again?" he added reproachfully.

"No, I haven't," replied Tom.

He could have bitten his tongue out the next minute, for Jack said eagerly, "Then you've got it?"

"Yes, I have," said Tom slowly; "but look here, Jack, I don't like using it, I feel like a thief, and wish I hadn't touched it."

"Don't be a stupid!" retorted Jack in a tone of contempt. "I was half afraid you'd funk over the job, but as you've done it, why I think all the better of you for it."

"I wish I hadn't touched it," exclaimed Tom, with a sigh.

"Oh, that be bothered for a tale—do you think you're the only sharp chap in London that'll make money out of Tittlebrat with borrowed money? I tell you what, it is done every day by them as know how to manage, and nobody none the wiser, and they all the richer."

"I don't care so much about being rich just now, I only wish I was honest," said Tom with a sigh, fingering the money that still lay safely at the bottom of his pocket.

Jack was afraid that if this mood continued, he would not get the money after all, and so he said, "Look here, I can't stop talking goody-goody Sunday-school sermons now, I must get back or I shall catch it. Give us the money, for bets at the price I told you must be handed over to-night, and so if we are to clear our little commission out of Tittlebrat, I must be going and sharp too."

Most reluctantly did Tom hand over the ten shillings he had taken and his own shilling, by way of commission.

And having secured this, Jack did not fancy walking further just now with Tom, for he was not a very lively companion this evening. So he turned off down one of the streets in City Road, and Tom went on his solitary walk to Islington.

He blamed himself bitterly now for giving up the money, for the thought that he was a thief would not be put aside, and he wondered what would become of him if he did not get this money back to put in his master's desk, for detection would be certain sooner or later if he failed to restore it.

He reached home silent and moody, and to his aunt's question whether he was going out, he replied, he did not care about it, he felt tired—which was true in a certain sense, for he felt utterly wretched, and wanted to go to bed and to sleep, that he might forget what had happened for a little while at least.

So he went to bed early, but he lay tossing about quite unable to go to sleep, or to think of anything but the events of the afternoon, the taking the money, the commendation of Mr. Phillips, and the meeting Jack and giving him the ten shillings.

He called himself all the fools he could lay his tongue to now for parting with this, for if he had not given it up to Jack, he could have taken it back the next day and replaced it in the desk, and if it was found out that the entry in the book and the date when the bill was receipted did not quite agree, he could tell Mr. Phillips how he had been tempted and had repented, but now there would be no such way of escape for him.

After a miserable, restless night he got up, still feeling unhappy and half afraid to go to the office, for fear something had occurred to bring his guilt to light.

But Mr. Phillips met him with a cheerful nod, and he went to the desk again, but he had no disposition to touch the money which passed through his hands to-day.

At dinner time Bob was full of the coming races, for he and one or two other lads had made up their minds to win some money out of it. Warrior was the favourite with Bob it seemed, and in listening to their talk about this horse and its different points, Tom forgot his misery for a little while. He did not say that he had staked anything on this race, and was sorry to hear that Bob felt so sure Warrior was going to win, that he had parted with all the money he had saved to buy his mother a warm shawl for the winter.

His mother was a widow, he knew, and had to work very hard, Bob had told him. The boy was very fond of his mother, and it would grieve him to have to tell her that he could not buy the shawl, and Tom wished he could give him a hint of how things really were, and that all his money would be lost.

Nothing could be thought of or talked of by the boys out of office hours but the coming race. All that they could possibly scrape together had been staked on the issue, and when at last the day came, they all trooped down to Fleet Street, without regard to their dinner, eating a bit of bread and cheese as they ran, all eager to know the result of the day's race.

Tom felt almost sick with anxiety, he had not been able to eat any breakfast, and now it seemed that the bread and cheese would choke him. But he managed to keep up with the rest, however, and got to the shop window where there was already a crowd waiting. But the result had not been telegraphed from Leicester, where this race was to be run, and so the crowd edged themselves as close together as they could, and prepared to wait until the news came, or they were compelled to leave by the lapse of time.

But the race in which the lads had interested themselves was to be one of the first run, and so they did not have to wait long before the news was flashed from the northern town to this Fleet Street newspaper office, and almost as soon as it was known inside, it was made known to the waiting crowd in the street.

With straining eyes and senses almost reeling from the intensity of his anxiety, Tom heard the name of the winner proclaimed. "Tittlebrat is first! Tittlebrat is first!" came the cry in all the varied intonations of rage, despair, triumph, and relief.

To many a foolish young fellow gathered round that window, it meant misery and ruin, for what did they know about horses or the ways of managing them? They had learned which was the favourite each in his own way, and now that an outsider had won, they felt they had been cheated, duped; but what could they do? They might feel morally certain there had been unfair play somewhere, but they could not prove it, dared not say they had suffered by it, but in grim silence must bear their wrongs and disappointment, though it should mean starvation and perhaps a felon's lot in prison for the next few years.

To Tom the relief was so great that he reeled, and would have fallen, if the good-natured Bob had not caught him as he was slipping to the ground.

"Hullo, old fellow, are you hit as hard as that?" he said in a tone of compassion. For all his little store of hardly gathered shillings had been swept away, and he made sure Tom had also betted on the favourite, although he had been so quiet about it.

"All right," gasped Tom, after he had rested on the pavement a minute. "I'll get up now," he said, "or the police will be asking what is the matter."

"Oh, the police are used to a crowd here on a race day, and won't notice it. Are you hit over Warrior like the rest of us?" he asked.

But Tom shook his head. "I went on Tittlebrat," he said, and try as he would, he could not help the tone being a triumphant one.

AN ESCAPE FOR BOB.

"SO you went on Tittlebrat," repeated Bob, as he walked down Fleet Street with Tom after he had recovered from the fainting fit into which he had been thrown by the news.

Bob was wishing more than ever that he had not been laughed out of his principles, for if he had only been firm in holding fast to his Sunday-school, this certainly would not have happened to him, for betting had no temptation for him, until he had given this up and tried to do as the rest did.

"Where did you get the news about Tittlebrat?" he asked, rather ruefully, as they walked along.

"Oh! A friend of mine told me about it," answered Tom.

"Well, you knew I was going to put all my money on the other, you might have given me a hint about this," said Bob in a reproachful tone. "I wouldn't care so much if it wasn't for mother's shawl, but I've been saving my overtime money for that all the summer, and she will be vexed when she knows I've just been and thrown it all away; and the way I've lost it will be worse than all to her."

Tom felt sorry, but he was not in the mood to take the blame of Bob's disaster. "Wasn't you all dead-set on Warrior?" he said.

"Well, that may be, but still, if I'd got to know that another horse was sure to win, I would have given you and the other chaps a hint about how the land lay," answered Bob in the same reproachful tone.

"Well, I had to pay for my tip. Business is business, you know."

But Bob could not help feeling hurt at what he regarded a gross breach of friendship on the part of Tom, for he knew well enough that if the case had been reversed, he would have given his own particular friends no peace until they had put their money on the horse he considered was sure to win.

It was a revelation to the lad when Tom went on to speak of it as business, where everyone was bound to consider themselves first.

"Well, if friends ain't to be friends in this, I'd like to know what the good of it is, and if that's the way racing is to be looked at, I'll take good care I never have any more to do with it."

Poor Bob went home almost heart-broken over the loss of his mother's shawl, for so sure had he felt that he should win what he had risked, and a considerable sum besides, that he had arranged with her to go with him to buy it early the following week; and it would be hard to tell which had looked forward to it with the greatest pleasure, Bob or his mother.

Now for him to go home and have to tell her that the thin old shawl would have to be worn through another winter was bitter indeed to the lad, for he had begun to think he might be able to add a bonnet to the shawl, and then they might both go to church on Sunday. If anyone had told them that this bitter disappointment was the greatest blessing that could be bestowed upon Bob just now, they would scarcely have believed it, for the widow had already told some of her neighbours what her son Bob was going to buy for her Christmas present, and now to hear that he had no money left was a sad blow to her.

His mother was ironing when Bob went home, for she was a widow and maintained herself by laundry-work. She turned to him with a smile of greeting as he came in, but the boy's white face made her put down her iron and she asked him, in some consternation, what had happened.

"Have you lost your place?" she asked, for nothing short of this she thought could account for Bob's downcast looks.

"Worse than that, mother," said Bob, with a half suppressed sob; "I've lost your shawl."

"Lost my shawl! Bless the boy, it ain't bought yet," replied Mrs. Ronan, with a puzzled look on her face.

"No, mother, I've lost the money, though, that was to buy it."

"But I thought you told me last week that it was your overtime money, and that you'd put it in the Post Office to take care of. Surely that ain't gone and bust up like the banks do sometimes?"

Bob wished it had just then. Anything would be easier than to tell his mother he had taken it out to bet on horse-racing, for she had warned him against this only a few weeks before.

She had heard nothing of the matter since, and so she supposed that he had kept his promise, and had given up all games of chance as she had begged he would.

To hear therefore that he had drawn out all this little store of money to bet on the races was a cruel blow to her, and she dropped in her chair as though she had been shot when she heard it.

"Oh, mother, don't cry," said Bob, bursting into tears himself, and trying to draw her apron down from her eyes. "Don't, mother, don't," he pleaded.

But the poor woman felt too heart-broken to dry her tears at once, and for a few minutes the two cried together.

"Oh, Bob, I have been so proud of you," she managed to say at last; "I have told everybody what a good, steady lad you were, never giving me any trouble, but always ready to give me a helping hand with a basket of clothes when you came home, and never spending any of your money on yourself, but just saving up your overtime money to buy me a warm shawl for the winter. And then for you to tell me you've just been and done the very thing I asked you not to do. Oh dear, oh dear! What will happen next?"

And the poor woman burst into a fresh flood of tears over the downfall of her hopes in her only son.

"Mother, you'll just break my heart if you go on like that," sobbed Bob; "say you'll forgive me, and I'll never bet on horses again, and I'll never play pitch-and-toss any more, and I'll go to evening-school and see if I can't learn to write better, and do sums quicker."

Bob knew how anxious his mother was for him to go to Sunday-school again, but hitherto, he had resisted all her persuasions for fear his companions at the warehouse should find out that he had gone back, after telling them he had left.

To hear, therefore, that Bob would conquer his pride and the fear of his companions' ridicule made the poor woman more hopeful for her boy's future. "Not that I'm the only one you've grieved, Bob," said Mrs. Ronan, wiping her eyes and looking straight at her son. "I hope you don't forget that you've grieved God a good deal more than you have me, badly as I feel about it."

Bob hung his head and did not reply. He had not thought of his fault in this light at all, but as his mother spoke, he recalled what he had often heard at school—about the unfairness, and the selfishness that all games of chance lead people to commit, and he remembered how he had complained of Tom Flowers not telling him how he might have avoided losing his money.

"I see, mother," he said slowly, "people who gamble and bet can't do to others as they would have others do to them. That's what Tom said to-day, when I grumbled because he didn't tell me all he knew about these races. He said everyone must be for himself in this, and look after the main chance."

"Yes, I suppose so, and the Lord Jesus Christ says, If anyone will be My disciple let him deny himself, which is just the opposite of what these racing people say."

"But I wouldn't have served Tom Flowers as he served me," protested Bob, in some indignation.

"Perhaps not just at first, but I daresay you would have come to it by-and-by; for what the Lord Jesus taught us as the golden rule of conduct between us and our neighbours—to do unto others as we would wish them to do to us if we were in their place, is quite impossible in all gambling and betting. You can see this for yourself. You say this Tom is a nice friendly lad, and yet he never told you what he had heard to save you from losing your money. Don't you see, that those who win must do so at the expense of those who lose; all cannot win, and, therefore, your gain must mean loss to somebody else, and so you profit by robbing another of his money—it is little better than robbery," concluded Mrs. Ronan.

"I see, mother," said Bob, humbly, "and if it wasn't for your shawl, I should feel rather glad that I hadn't won, for I should wonder now who had lost the money I had got."

"Thank God you didn't win, for if you had, you would never have thought about it perhaps, but only got into the habit of wanting and spending money, until this betting became a habit too, and then whatever money you might win, would cause you to be a ruined lad—ruined in body and soul, so I can thank God for the loss of my shawl, since it may be the means of saving my boy," said the widow.

"And you think the game of pitch-and-toss is as bad as betting?" said Bob, but it was more in the way of confession than asking a question.

What his mother said had so touched him, that he thought he had better make a clean breast of it, and let his mother know the worst at once, though it would grieve her, he knew, to hear how every consideration of right and wrong had been given up since he left the Sunday-school.

"Oh, Bob, you know as well as I do, that pitch-and-toss is only gambling. Didn't you see some boys taken up by the police for playing at this game only last week. Oh, my boy, my boy, I little dreamed—"

And here the widow's tears choked her voice, and she put her arms about her boy's neck, and they cried together for a few minutes again.

But at last Bob said, "Mother, I'll never do it again, I promise you. Ask God to forgive me, and—and—"

"Let us kneel down together and ask Him to forgive you for the past, and to help you keep the promise you have just made to me. Without His help you will fall again, even though you do go to Sunday-school. Don't forget that, Bob, it must be in God that you trust, not your school or your teacher. Now let us ask God for this," and together they kneeled down, and the widow poured out her trouble before God, but did not forget to thank Him that her boy had been stopped in his downward course.

And then she prayed that if there were any among his companions who had been led away by his bad example, they, too, might be brought back to the path of right, even though the way back should be painful to tread.

The widow did not know why she was led to pray thus, and certainly did not know how greatly poor, foolish Tom Flowers needed her prayers just then. But she did know how one boy's example influences another, and she thought it might be possible that Bob had thus helped to lead another boy astray, by his bad example at least.

When they rose from their knees, Bob said, "I think I should like you to tell teacher all about it, mother. He ought to know before I go back to school, but I shouldn't like to tell him."

"Very well, you go round to the school presently, he will be there to-night, and ask him to come in and see me."

Bob hardly liked to go upon this errand, but his mother said he must, and so after tea he went, looking very sheepish as he went into the school, where so many of his old companions were gathered now.

"Well, Bob, have you come back to us again?" said his teacher, when he saw him.

"I'm coming, sir, but I'd like you to see mother first, if you wouldn't mind coming in to speak to her as you go home."

"You haven't lost your place, I hope, Bob," said the gentleman, noticing the boy's serious looks.

"No, sir, it's nothing about my place," said Bob; "but mother wants to see you before I come back to Sunday-school."

"Well, I'm glad you're coming back," said the gentleman. "I'll come in as I go home."

Bob contrived to be out of the way when his teacher came in, that his mother might have her talk with him alone. But he kept his promise and went to school on Sunday, and also joined several of the classes held on week evenings for the improvement of those who desired to continue their education.

Bob determined to apply himself to arithmetic and writing, for he had seen by the way in which Tom Flowers had been chosen for office work, that if he was to rise and be a help and comfort to his mother by-and-by, he must strive to improve himself in this, and in reading and spelling too.

Mrs. Ronan was well pleased to see that Bob was determined to turn over a new leaf entirely as to his conduct. But as he sat at tea a few days later, she thought she would give him a word of caution to be careful, and not to forget to ask God's help for the future.

"I'm not likely to forget what a fool I have been while that shabby old shawl hangs there," said Bob. "I'd a good mind to sell my great-coat yesterday, for I hate to see you go out in that old shawl this bitter cold weather." And he looked at his mother to see how she took this proposal about the coat.

"I should have been very cross if you had sold the coat. You will have to bear the sight of the old shawl as a lesson, though I don't mind it a bit now," she added.

"That don't make up to me for the shawl, though," said Bob, with a sigh.

"Perhaps not to you, but if I see you working steadily at these school lessons, I shall feel proud of you yet, Bob, though you did take me down a peg or two over that shawl I'll not deny. For I had counted on it, and told Mrs. Hooper about it, and we had discussed what the shawl should be, until I felt almost as though I had been robbed when you came and told me I could not have it."

Bob sighed. "Poor mother, I was sorry to have to come home and tell you about it. I had some thought of running away instead of coming home that night, for I didn't know how I was to tell you what a fool I had been."

"That would have been mending matters with a vengeance," said Mrs. Ronan, with a scared look in her face that such a thought could enter her boy's head. "Why, what do you think I should have done then if you had gone?"

"I suppose I was thinking more about having to tell you and how I could get out of it," admitted Bob frankly.

"Yes, how you could shirk being made uncomfortable by what you had done. That is the reason most people run away from their duty, and, like the cowards they are, care nothing for the trouble and grief they cause their friends. I am glad you were brave enough to come and tell me all about it. We have both had to suffer some pain, but it may be a useful lesson to us both, and I feel sure now I shall be as proud as ever of my boy, in spite of what has happened."

"So you shall, mother," said Bob heartily, "I mean to stick to Sunday-school now I have begun again, and I mean to try my hardest at the writing and arithmetic, so that I may get a rise some day, and save you from working so hard at the washtub."

"Well, of course, I shall be glad for you to get on, my boy, but I want to see if you can't do something to induce your friends at the warehouse to give up all gambling games."

"Ah! That's easier said than done," said Bob, with something of a sigh as he rose from the tea table. "You see, if you ain't in the swim with the rest you're just nowhere, and that's where I am now. They've found out that I have gone back to school, and as I don't join in any of the games, they take care not to let me know what is going on among them. That was just how it was I had to join in with them before. A chap has to do like the rest for peace sake."

This was all Bob said, but his mother knew that her boy was having a hard fight, and she took care that his struggle was not made harder when he came home. The old shawl was put out of sight for a time, for the boy had no need of this to remind him of what had taken place, and since it had become a reproach to him, she resolved that he should not see it more than she could help.

APPLES OF SODOM.

TOM went home the evening of the race, feeling wonderfully elated, hugging to himself the knowledge of his good fortune, but not daring to let his aunt know anything of it. He had to sit and eat his bread and butter at tea time as though nothing had happened, which in itself was almost a pain just now. For he was bursting to tell the news to somebody.