Large-size versions of illustrations are available by clicking on them.

SURVEY DEPARTMENT,

EGYPT.

THE TOPOGRAPHY AND

GEOLOGY

OF THE

FAYUM PROVINCE

OF EGYPT

BY

H. J. L. BEADNELL, F.G.S.,

F.R.G.S.

![[Decoration]](images/logo.png)

CAIRO

National Printing

Department

1905.

[3]CONTENTS.

| INTRODUCTION. | |

| Pages. | |

| Surveying operations. Soil survey. History of discovery of Fayûm vertebrate fauna | 9 |

| Part I.—TOPOGRAPHY AND STRUCTURAL GEOLOGY. | |

| Section I.—Cultivated Land— | |

| Area. Composition and character of alluvial soil. Connection with Nile Valley. Bahr Yusef and canal system. Ravines. Alluvial deposits of Lake Moeris and prehistoric lake. Increase of cultivated lands | 11 |

| Section II.—The Birket el Qurun— | |

| Site, depth and dimensions. Remnant of Lake Moeris. Continual shrinkage of lake. Deposition of sand in lake at present day. Salinity of lake. Possible underground outlets. Currents | 12 |

| Section III.—The Surrounding Desert Region— | |

| Area and limits of Libyan Desert described. Rocks forming the area. Importance of dip. Chief causes of origin of Fayûm | 14 |

| Section IV.—Wadi Rayan and Neighbourhood— | |

| Colonel Western’s survey. Sir William Willcocks’ report. Borings. Details of proposed reservoir. Schweinfurth’s estimate of salt content. Willcocks’ “Assuan Reservoir and Lake Moeris.” Detailed geological examination not yet undertaken. Traverse from Nile Valley through Wadi Muêla and Rayan to Gharaq. Warshat el Melh and springs of Wadi Muêla. Der el Galamûn. Pass from Muêla to Rayan. Sand accumulations. Wadi Korif. Springs of Wadi Rayan. Analyses and output of water. Geological succession in Wadi Rayan. General geology of floor and bounding walls. Ridge separating Rayan and Gharaq. Apparent absence of Nile deposit and freshwater shells in Wadi Rayan. Question of leakage through ridge. Permeability of Rayan if used as a reservoir. Salinity of water | 16 |

| Section V.—Central Area of the Region— | |

| Area and features. Dip-slope of surface. Drainage basins of central plain. Pools formed by rainfall. Tamarisk growth. The eastern area covered by alluvium. The bounding plateau to the north. Ghart el Khanashat dunes | 24 |

| Section VI.—The Ridge separating the Nile Valley and Fayum— | |

| Width and highest points. Strata forming ridge. Gravel terraces. Low points of ridge. Original access of Nile waters to depression. Formation of lake and deposition of sediment in Fayûm | 25 |

| Section VII.—The Northern Desert Region— | |

| Escarpments and plateaux. Extreme west and south-west limits of area. Ferruginous silicified puddingstone of ancient rivers. Jebel el Qatrani. Widan el Faras. Elwat Hialla. Garat el Gindi. Garat el Faras | 26 |

| [4]Part II.—TECTONICS. | |

| Section VIII.—Faulting and Folding— | |

| Origin of depression. Evidence in drainage ravines El Bats and El Wadi. Deep boring at Medinet el Fayûm. Dr. Blanckenhorn’s theory that depression owes its origin to extensive fault system. Fault theory disproved. Fault N.N.E. of Qasr el Sagha. Numerous local strike faults of small throw. Occasional influence of fractures in determining escarpments | 29 |

| Part III.—GEOLOGY. | |

| Section IX.—General and Classification of Strata— | |

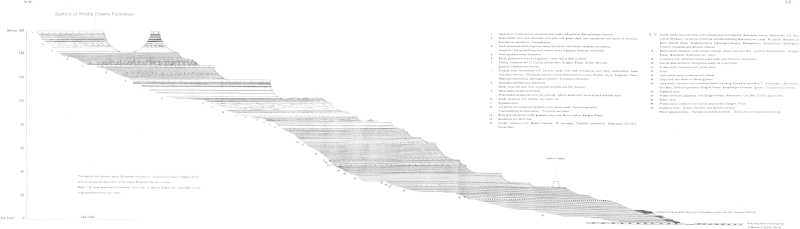

| Depression cut out in sedimentary rocks. Local lava flows. Dip. Oldest beds the Nummulites gizehensis limestones of Middle Eocene. Fluviomarine series of Upper Eocene and Oligocene age. Absence of Miocene strata. Pliocene, Pleistocene and Recent. Table showing succession and classification of strata | 33 |

| Section X.—Middle Eocene— | |

| A.—Wadi Rayan Series.—Work of Schweinfurth and Mayer-Eymar. Section at entrance to Wadi Muêla on Nile Valley side. Strata of cliffs near Der el Galamûn. Detailed section measured at Jebel Rayan. Mayer Eymar’s section in Wadi Muêla | 35 |

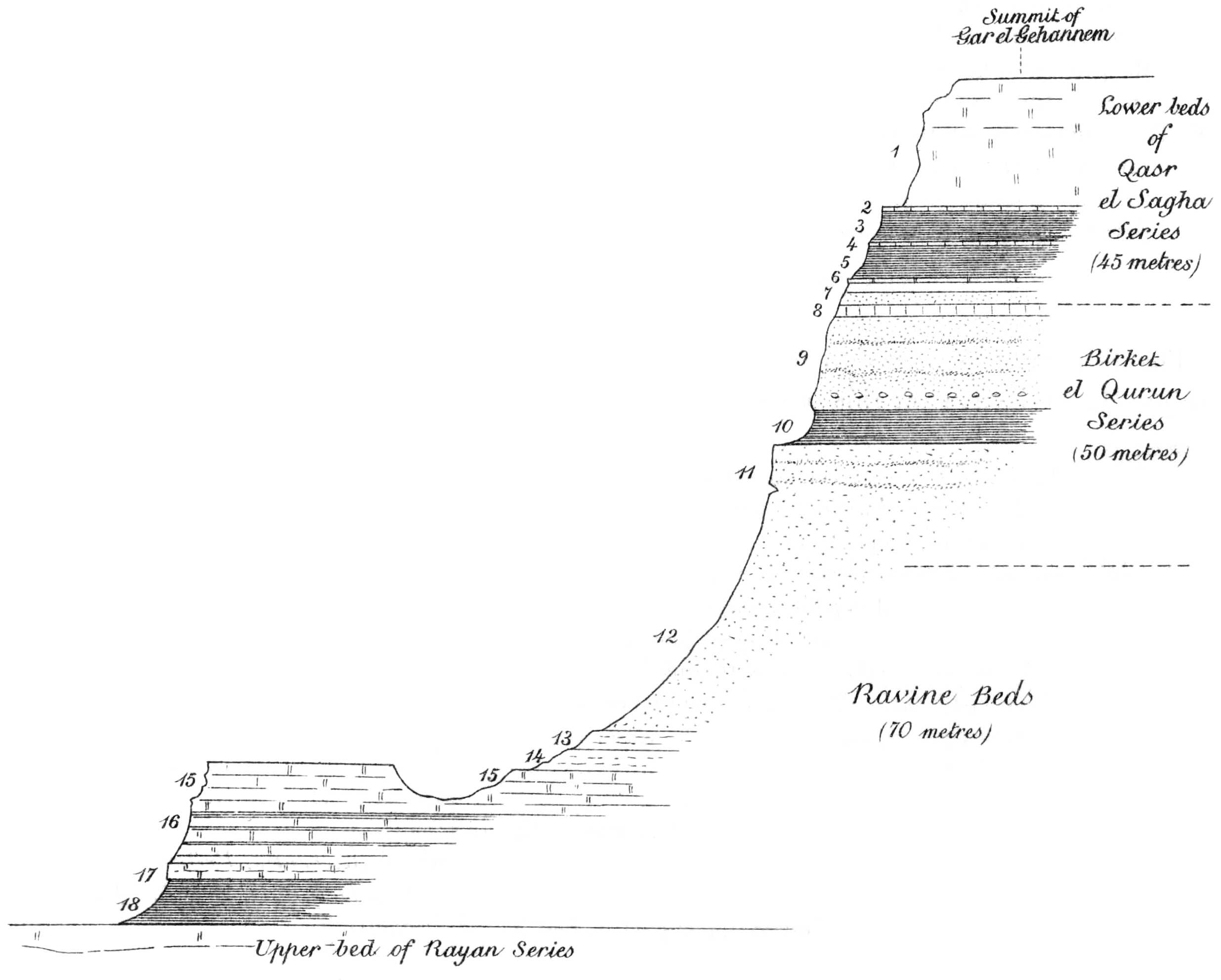

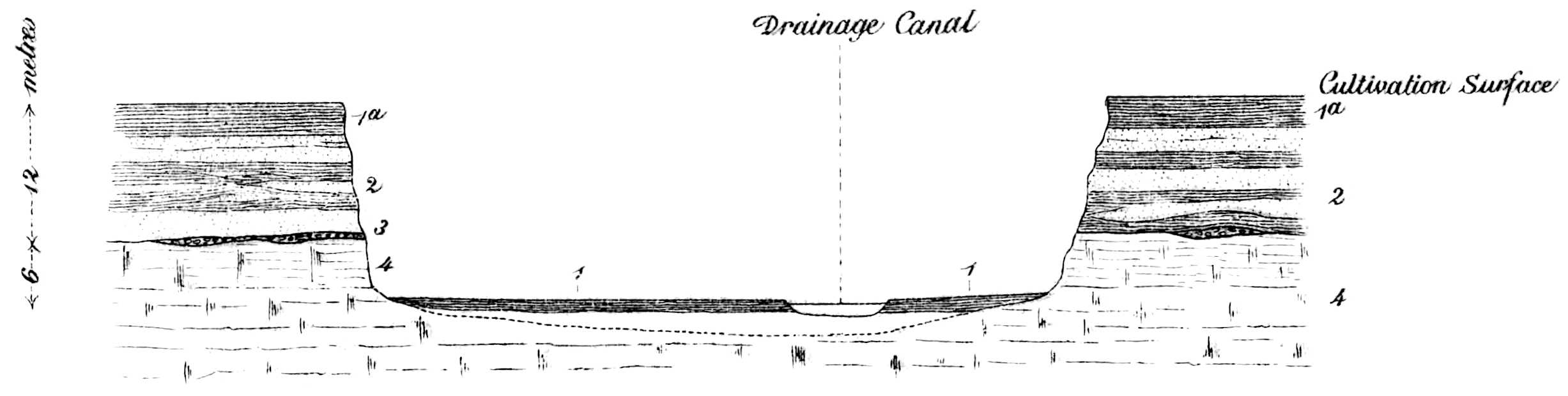

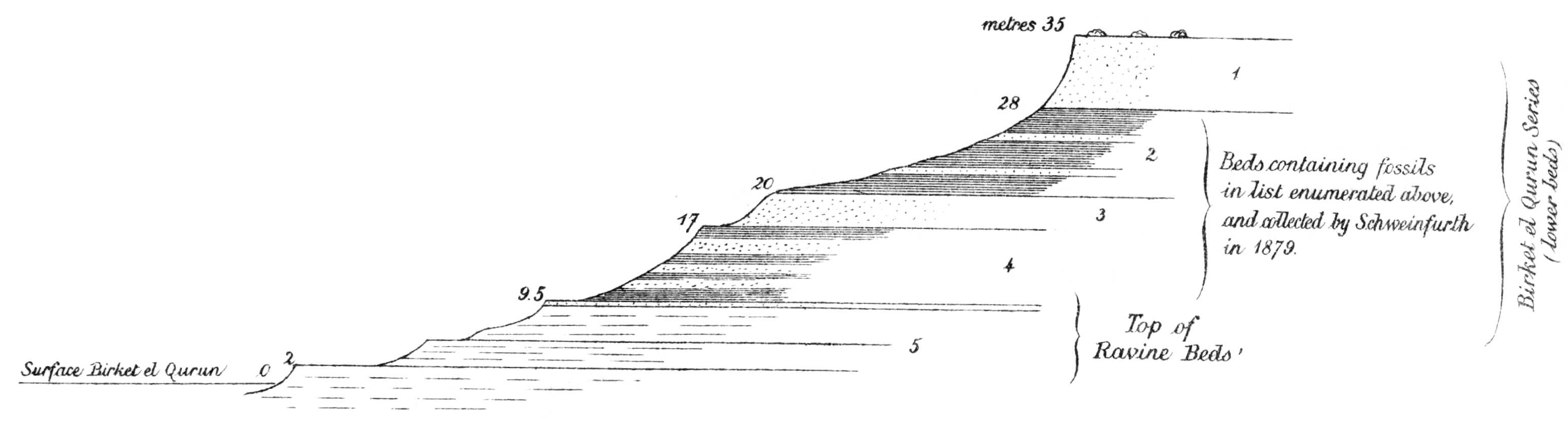

| B.—Ravine Beds.—In ravines of El Bats and El Wadi. Relation to underlying series seen at Gar el Gehannem. Section at Gar el Gehannem. Fauna of strata. In ravines unconformably overlain by Pleistocene, etc. Form plain bordering cultivation on east side. Extension into Nile Valley. Occurrence at Sersena and Tamia. Forming base of Geziret el Qorn and lower part of northern escarpment of Birket el Qurûn. West end of lake. Hard siliceous bands give rise to horns or promontories of lake. Ravine Beds in the Medinet el Fayûm boring. Thickness | 37 |

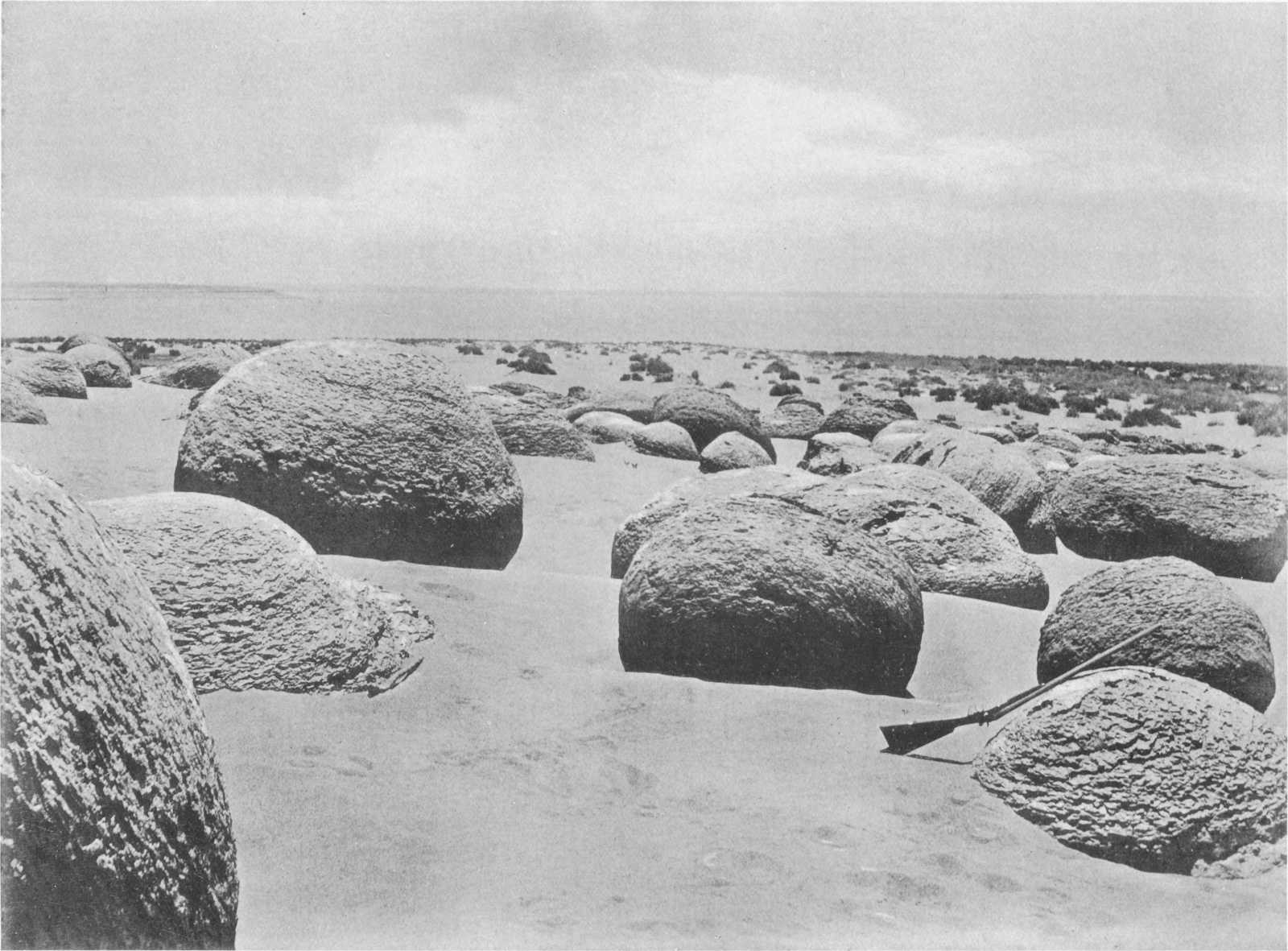

| C.—Birket el Qurun Series.—Homotaxial with quarried limestones of Cairo. Foraminiferal beds. Extension of series. Section at Ezba Qalamsha. Section north of Lahûn pyramid. East of Sersena and north-east of Rubiyat. Section 17 kilometres 28° N. of E. of Tamia. Series characterized by large globular concretions. Development and fauna in Geziret el Qorn. Zeuglodon remains. Profile at Geziret el Qorn. Rich molluscan fauna. Section on mainland opposite Geziret el Qorn. Section at west end of Birket el Qurûn. Formation of earth-pillars. Extension west of the lake. Development of the series in the Zeuglodon Valley. Abundance of skeletons of whales. Molluscan fauna. Pseudomorphs in celestine. Hill mass south of the Zeuglodon Valley. Junction of Birket el Qurûn series with overlying stage | 41 |

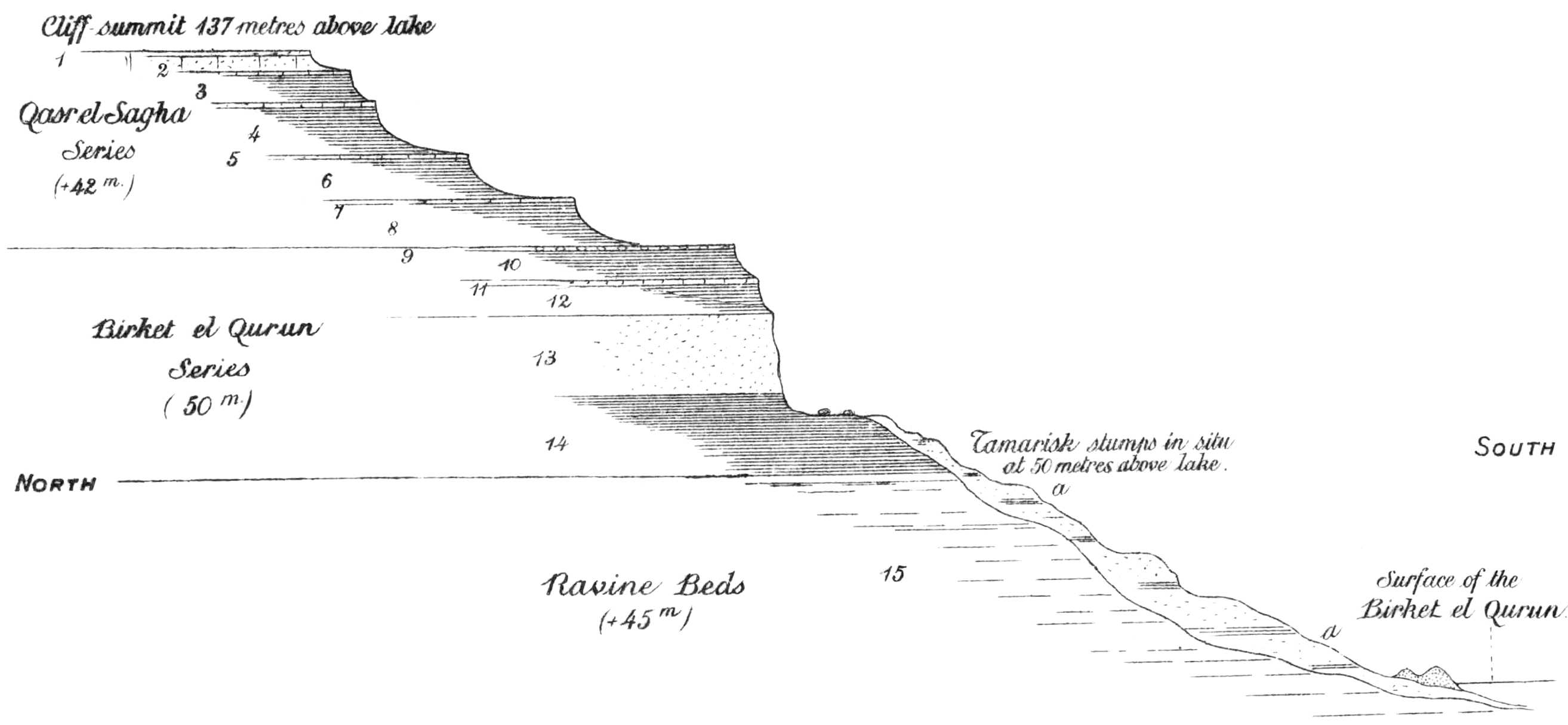

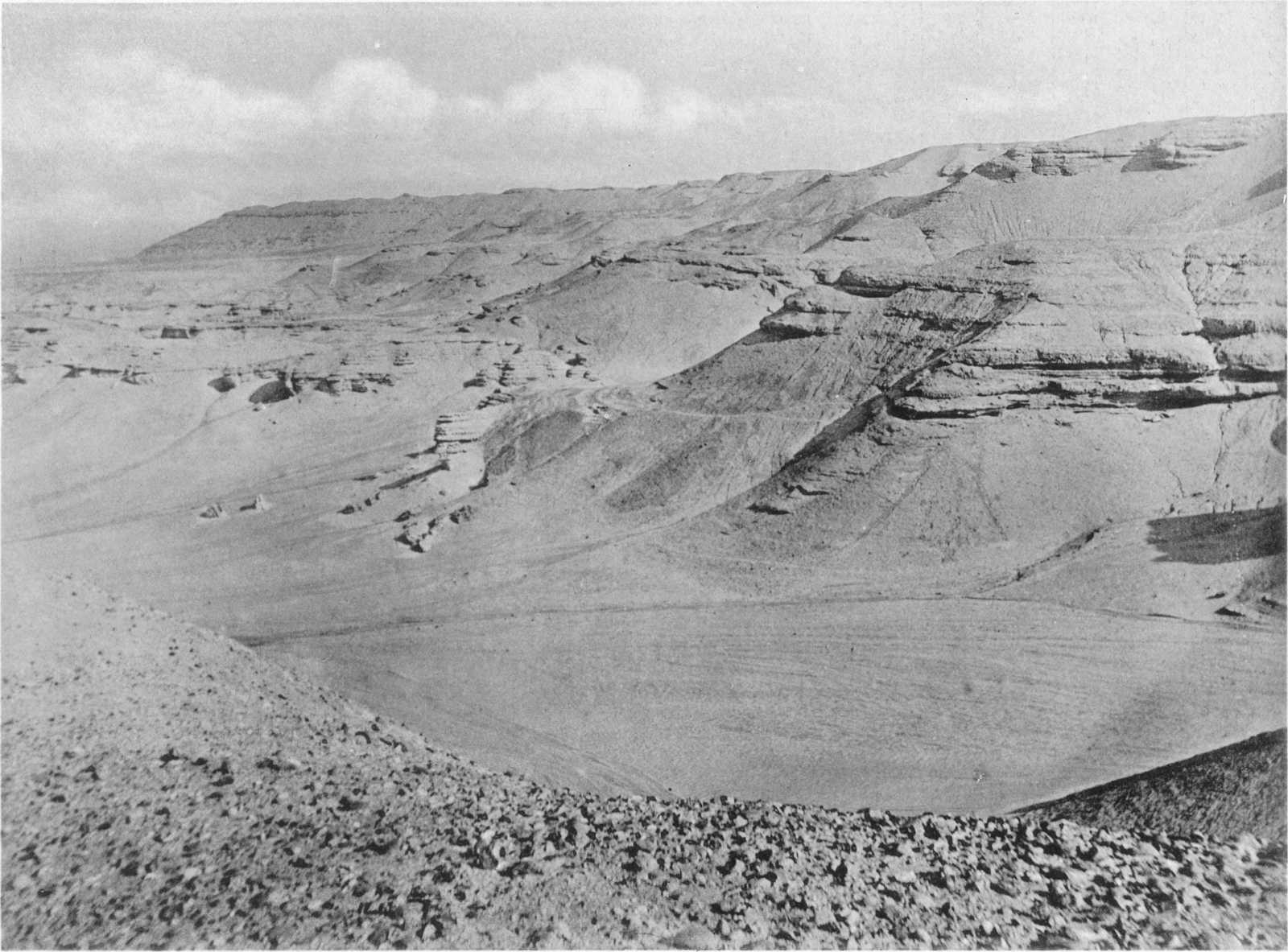

| D.—Qasr el Sagha Series.—Equivalent of the Upper Mokattam of Cairo. Greater development in Fayûm. Vertebrate fauna of series. Schweinfurth’s original discovery of cetacean remains. Recent discovery of land and marine mammals. Extension of series generally. N.N.E. of Tamia. At Garat el Faras. In the cliffs north of the Birket el Qurûn. Detailed section near ruin of Qasr el Sagha. At Gar el Gehannem and westwards. Land animals floated out from land by river currents. The series a littoral deposit. Lignitic beds and thin seams of coal | 49 |

| [5]Section XI.—Upper Eocene — Lower Oligocene— | |

| E.—Fluvio-marine Series.—Nature of sediments, Interbedded basalts in upper part. Character of its invertebrate fauna. Conditions of deposition of series. Continuance of similar conditions to Miocene and even Pliocene times. Bone-beds at base of series. Association of skeletons of animals and forest trees. Preservation of remains. Analysis of fossil bones. Relation of Fluvio-marine series to underlying stage. Characteristics of the group. Its development in the field. Its slight development at Elwat Hialla. Section near Elwat Hialla. Constant northerly dip. Organic (molluscan) remains 9 and 14 kilometres north of Qasr el Sagha. Detailed section from near Qasr el Sagha to Widan el Faras. Determinations of mollusca from the series. Tripartite character of the series west of Widan el Faras and Qasr el Sagha. Occurrence of calcite, gypsum and chalcedony. Tabular chert and flint. Ancient workings. Extent of basalt. Silicified trees | 53 |

| F.—Age of the Fluvio-Marine Series.—Difficulty in the determination of age owing to paucity of fossils. Zittel’s tabulation of “Schichten von Birket el Qurûn” as Oligocene. Mayer-Eymar’s age determinations. Schweinfurth’s comparison of the series with the Scutella beds of Der el Beda near Cairo. Blanckenhorn’s determinations. The stratigraphical position of the series and relationship to Qasr el Sagha series. Stratigraphically lower than the Lower Miocene of Mogara. Whole complex in all probability of Upper Eocene and Oligocene age, the transition being at or near the basalt sheets | 63 |

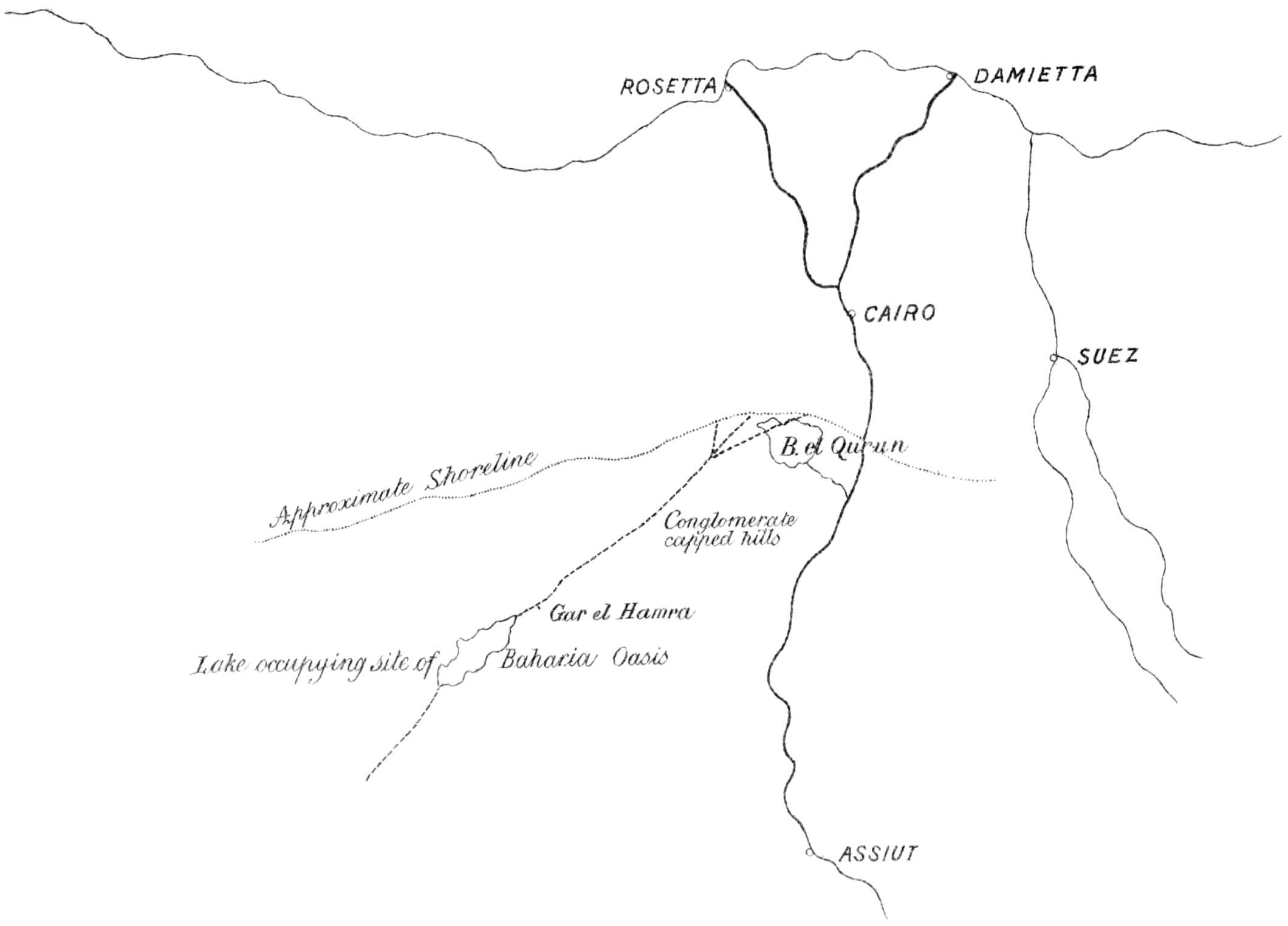

| G.—The Position of the Land Mass from which the Mammals were derived.—Proximity of continental land. Absence of branches on fossil trees. Massif of Abu Roash perhaps an island to the north. Extension of Eocene sea. Continual retreat of the sea northwards. Rivers emerging from the land. Number and positions of such rivers doubtful. Evidence for river passing from the modern oasis of Baharia through Gar el Hamra to the Fayûm. Lacustrine and fluviatile deposits along the course. Huxley’s theory of immigration and invasion of animals into Africa. Fayûm animals belong to an extinct African fauna of Tertiary times. Contains the earliest and most primitive forms of elephants and other groups. Emigration and immigration. Prof. Osborn’s theory of the African continent as a centre of radiation. Confirmation by the Fayûm mammal discoveries. List of new species obtained from the Fayûm | 65 |

| H.—The Absence of Miocene deposits in the Fayûm.—The Fayûm a land area in Miocene times. Miocene deposits of Mogara. Lithological similarity. Probable persistence of geographical conditions | 71 |

| Section XII.—Pliocene— | |

| J.—Marine deposits: Middle Pliocene.—Marine deposits of Sidmant with typical Middle Pliocene mollusca. Relation of these deposits to the gravel terraces as yet unknown though important | 71 |

| K.—Borings on Rock Surfaces; of doubtful age.—Apparently due to marine boring mollusca. No exact evidence as to age. (α) Low level borings from zero to 20 metres above sea-level. (β) High level borings at 112 metres above sea-level. Limited occurrences of borings | 71 |

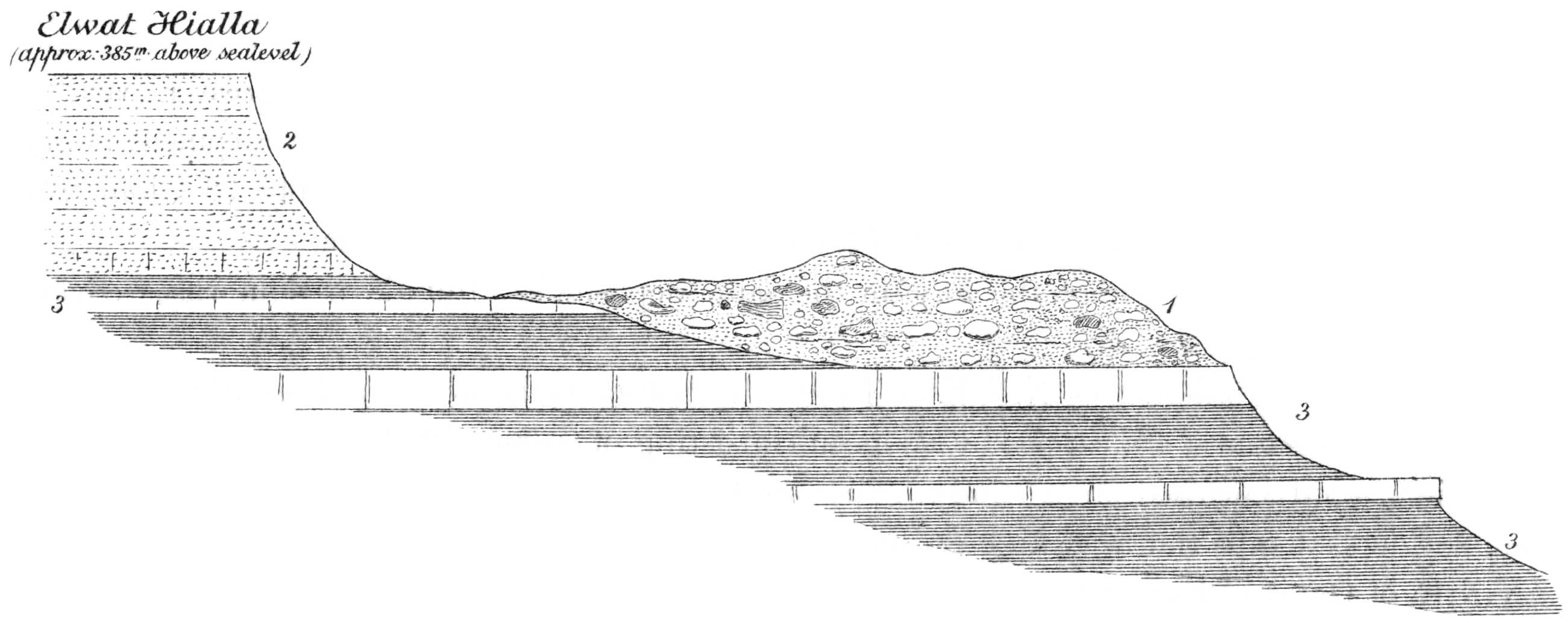

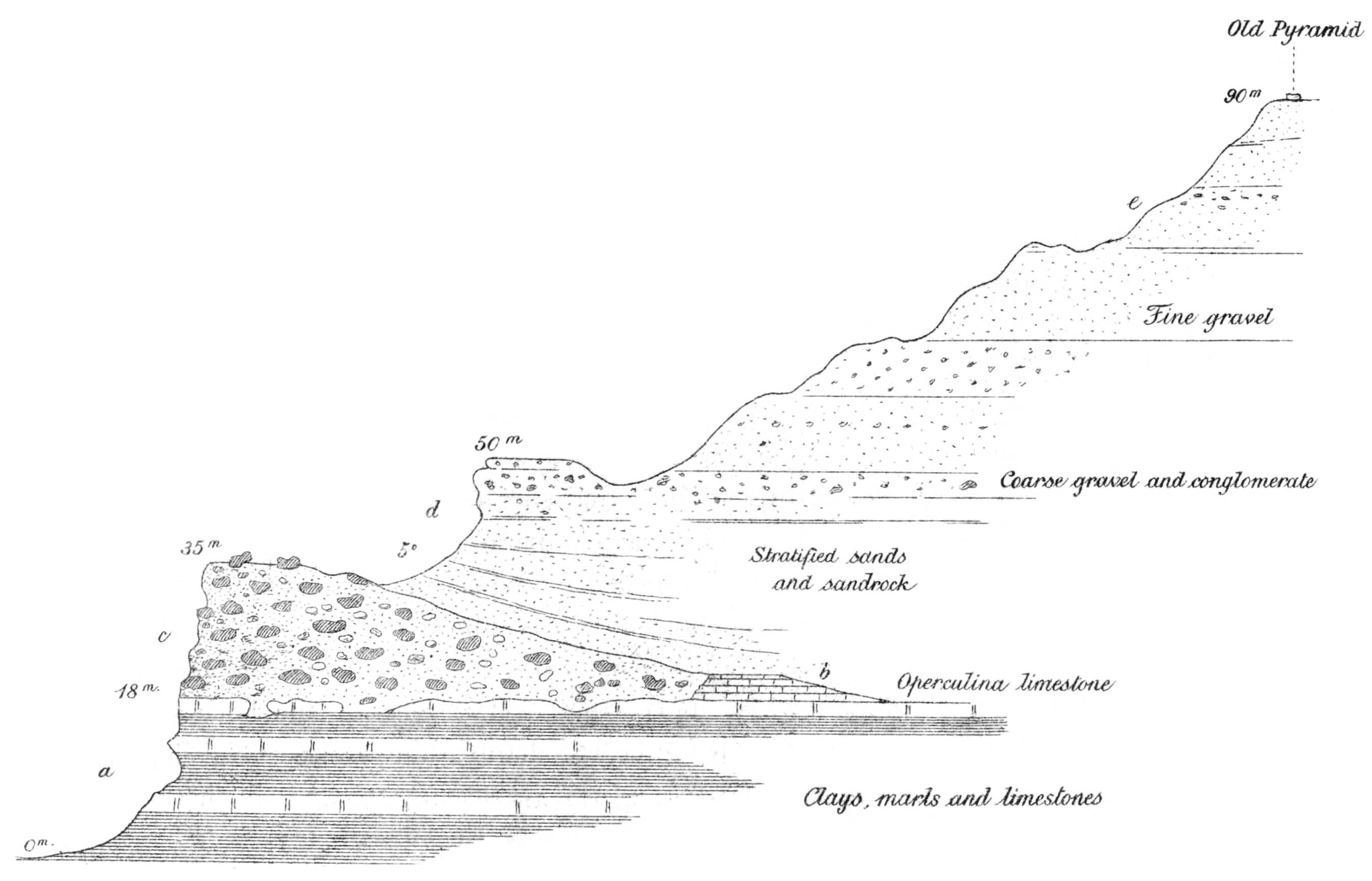

| L.—Gravel Terraces:? Upper Pliocene.—Well marked terraces of gravel up to 170-180 metres above sea-level. East of Sêla. Character of deposit. East of Sersena and Roda. N.N.E. of Tamia, N.N.E. of Garat el Faras, east and north-east of Garat el Gindi. Relation to different series. Character of gravels at Elwat Hialla. West of Elwat[6] Hialla gravel terraces almost completely removed by denudation. Traces near Widan el Faras and near Garat el Esh. Height of terraces in latter locality determined as 170 metres above sea-level. Terrace marks shore line of great sheet of water, whether freshwater or marine. The great plains of the Fayûm possibly in part plains of marine denudation | 73 |

| M.—Gypseous Deposits: probably dating from the close of the Pliocene.—Extension in Nile Valley and Fayûm. Section at Medum. On the east side of the Fayûm. Gypsum cemented conglomerate. Close connection with upper part of gravel terraces | 77 |

| N.—Summary of Pliocene Period | 78 |

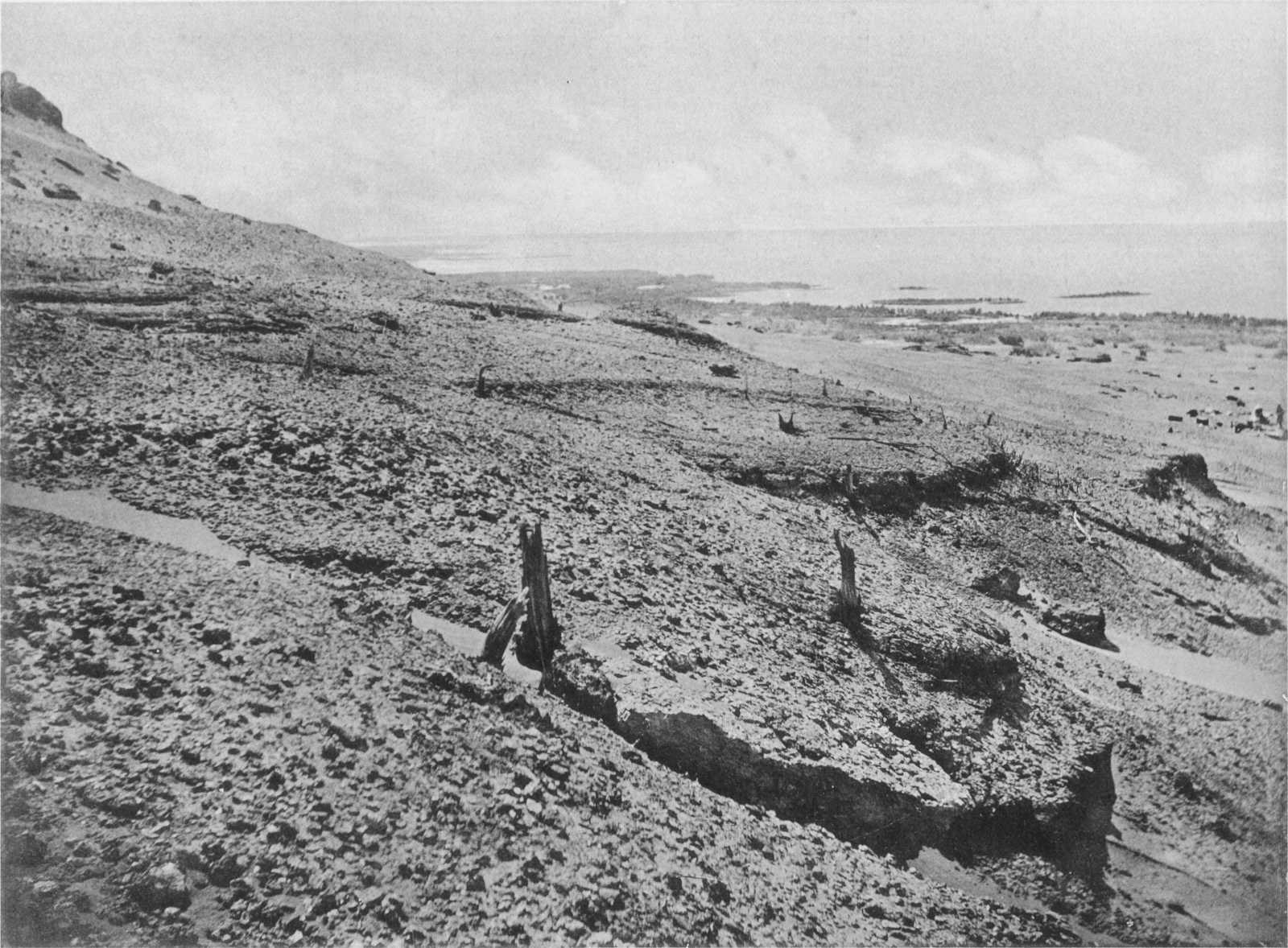

| Section XIII.—Pleistocene— | |

| Earliest existence of a freshwater lake. Probably not a remnant of the Pliocene sea or lake in which gravel terraces were formed. Intermediate denudation of area. Date of earliest entry of Nile waters doubtful. Freshwater lake of Nile Valley. Drainage down the Nile Valley and establishment of river. Breaking down of gravel ridge separating the valley and the Fayûm. Entrance of flood waters. Formation of lake and deposition of sediment. Subsequent disconnection of Nile Valley and Fayûm owing to erosion of river bed. Rise of Nile in prehistoric and historic times. Reconnection. Geological evidence for the existence of great freshwater Pleistocene lake. Position and dimensions. Fossil fauna of the lake, and its difference from all other Egyptian faunas. Blanckenhorn’s conclusions | 79 |

| Section XIV.—Recent | 81 |

| O.—Prehistoric.—Abundance of worked flints. Shores of lake inhabited by Neolithic and probably prehistoric man. Tamarisk remains. Probable age of flints anterior to Egyptian historic period | 82 |

| P.—Historic.—Relations of the Nile Valley river system and the Fayûm. Lake Moeris a regulator of the Nile floods. Brought under control in XIIth dynasty. Early references to Lake Moeris. Its position disputed in modern times. Linant de Bellefonds’ assertion disproved by Sir Hanbury Brown. Archæological evidence for the site. Present day fauna of the Birket el Qurûn. Modern deposits. Blown sand. Erosion | 82 |

| APPENDICES | 87 |

| 1. Previous literature relating to the Fayûm | 87 |

| 2. Fayûm lamellibranchs mentioned in Oppenheim’s “Zur Kenntnis alttertiärer Faunen in Ægypten.” | 89 |

| INDEX | 91 |

[7]LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| PHOTOGRAPHS. | |||

| Plates. | Page. | ||

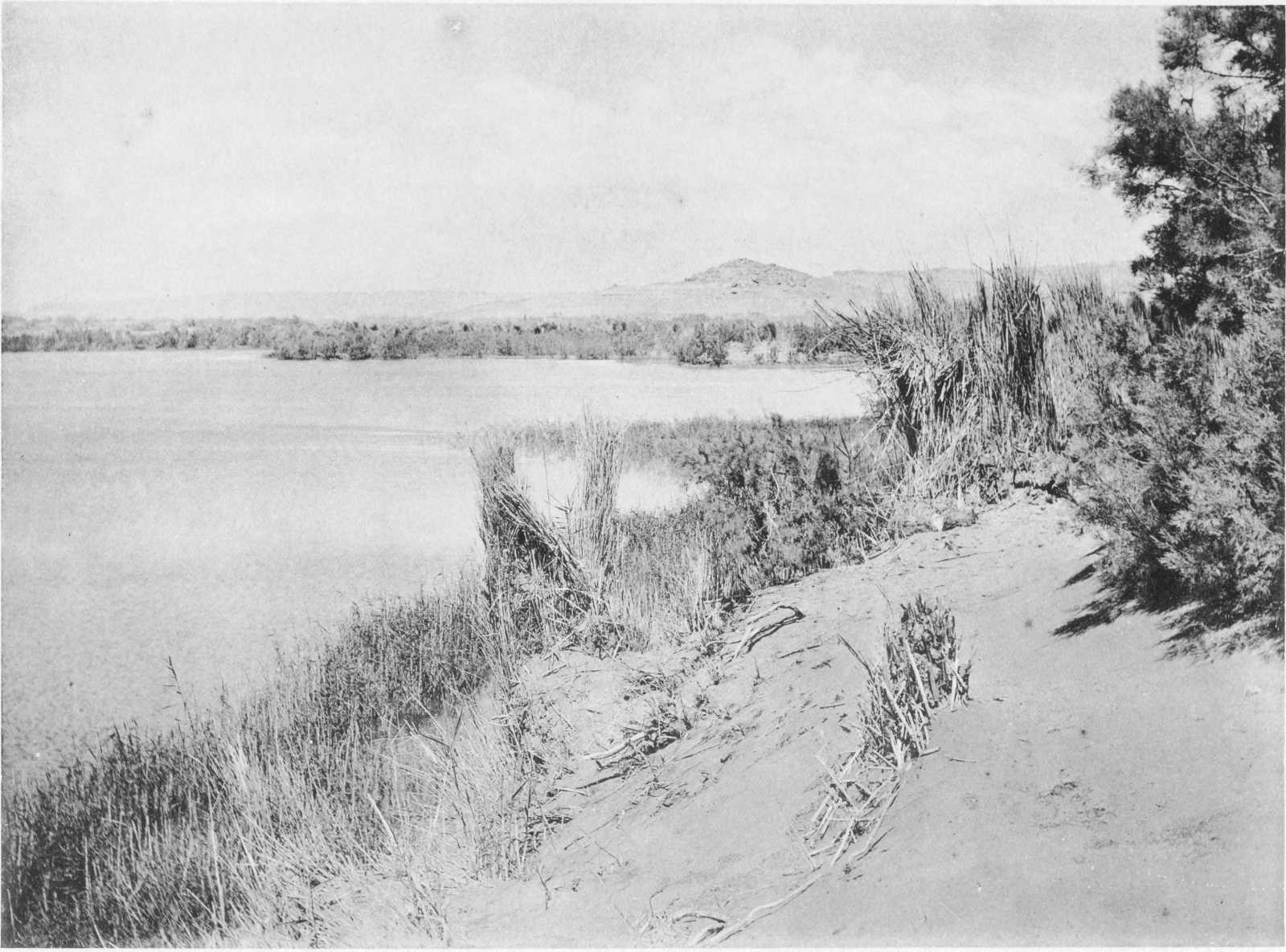

| I. — | North side of the Birket el Qurûn, looking west | Frontispiece. | |

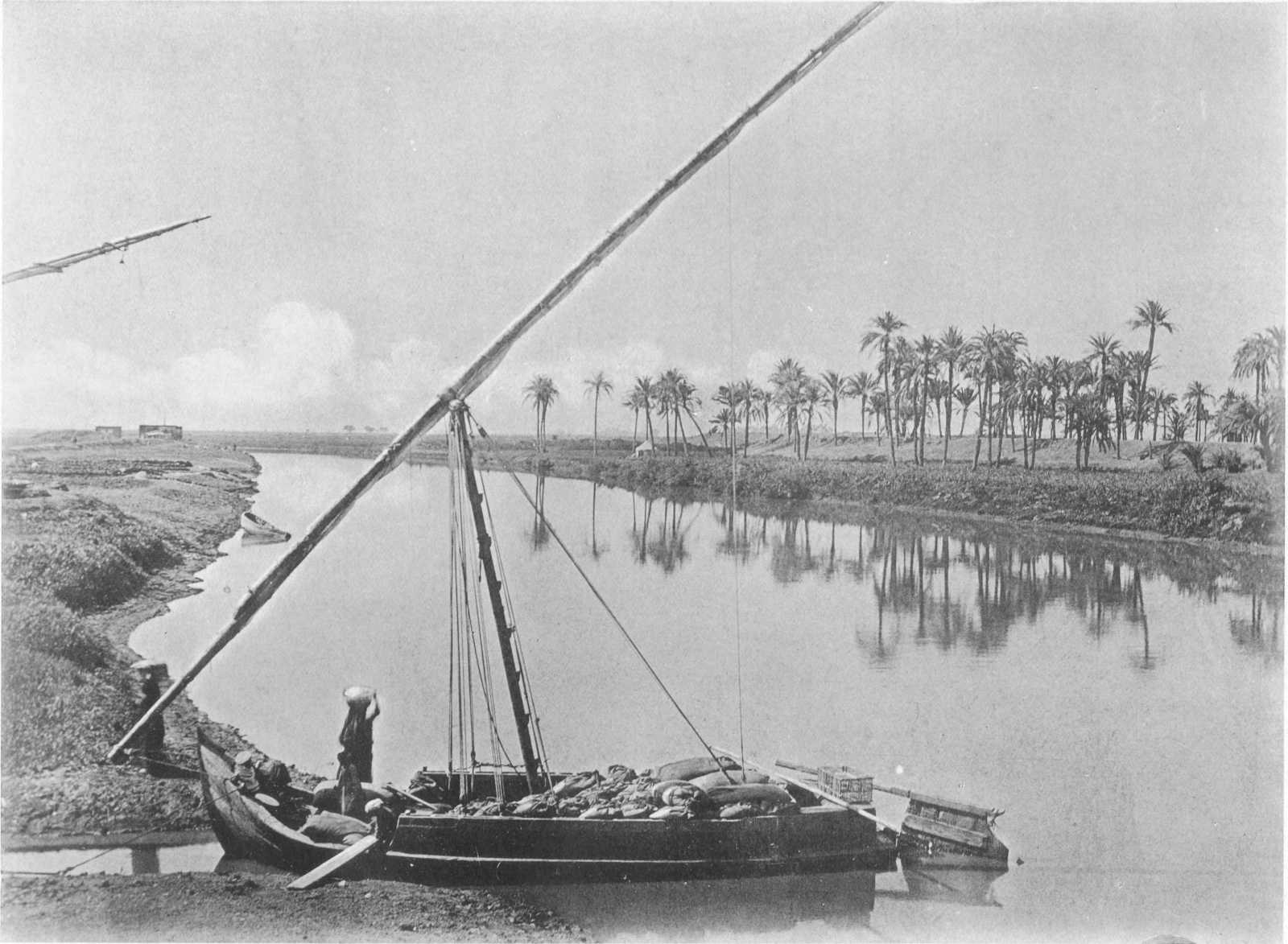

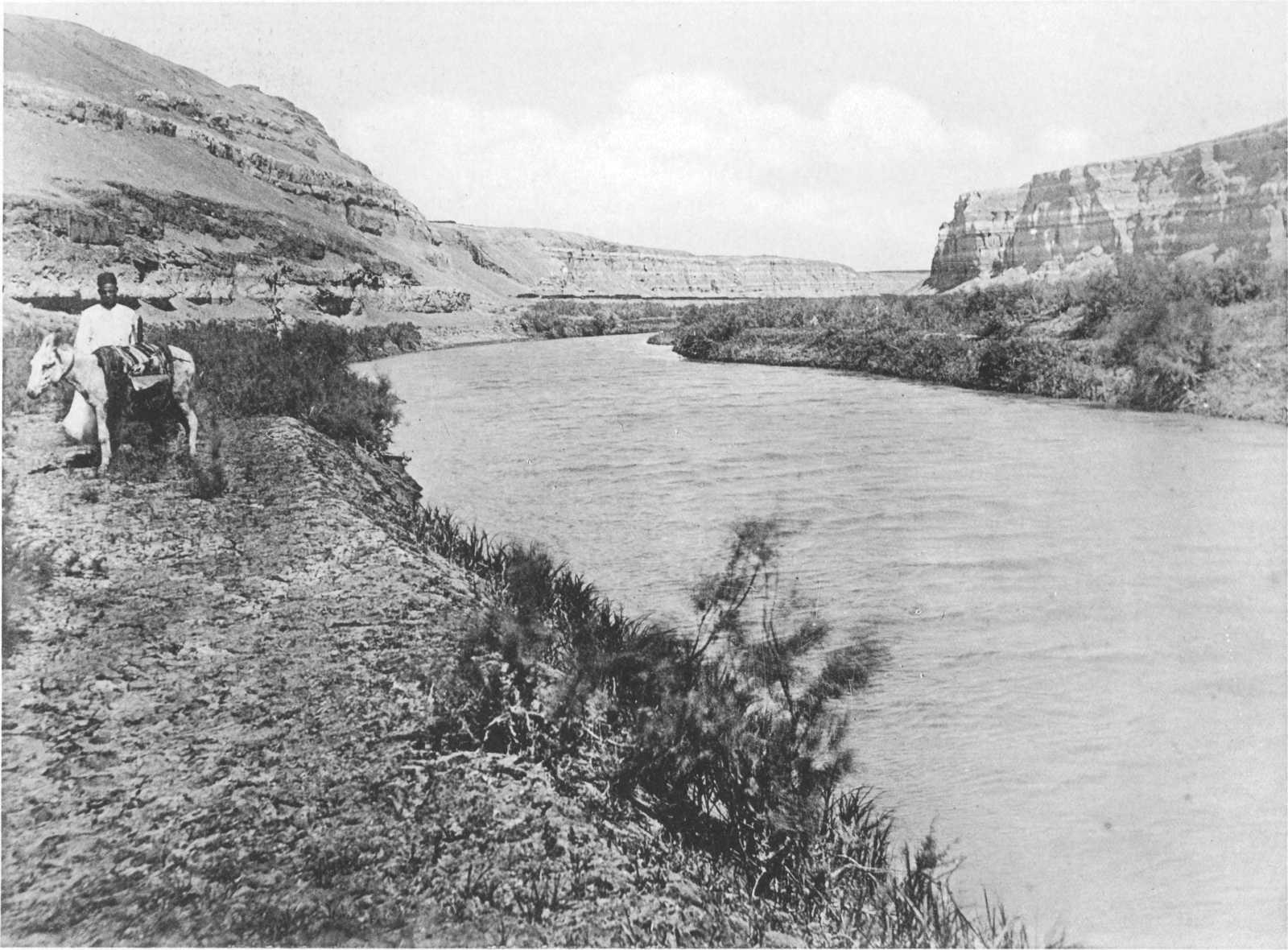

| II. — | Bahr Yusef at Lahûn before entering the Fayûm | to face | 11 |

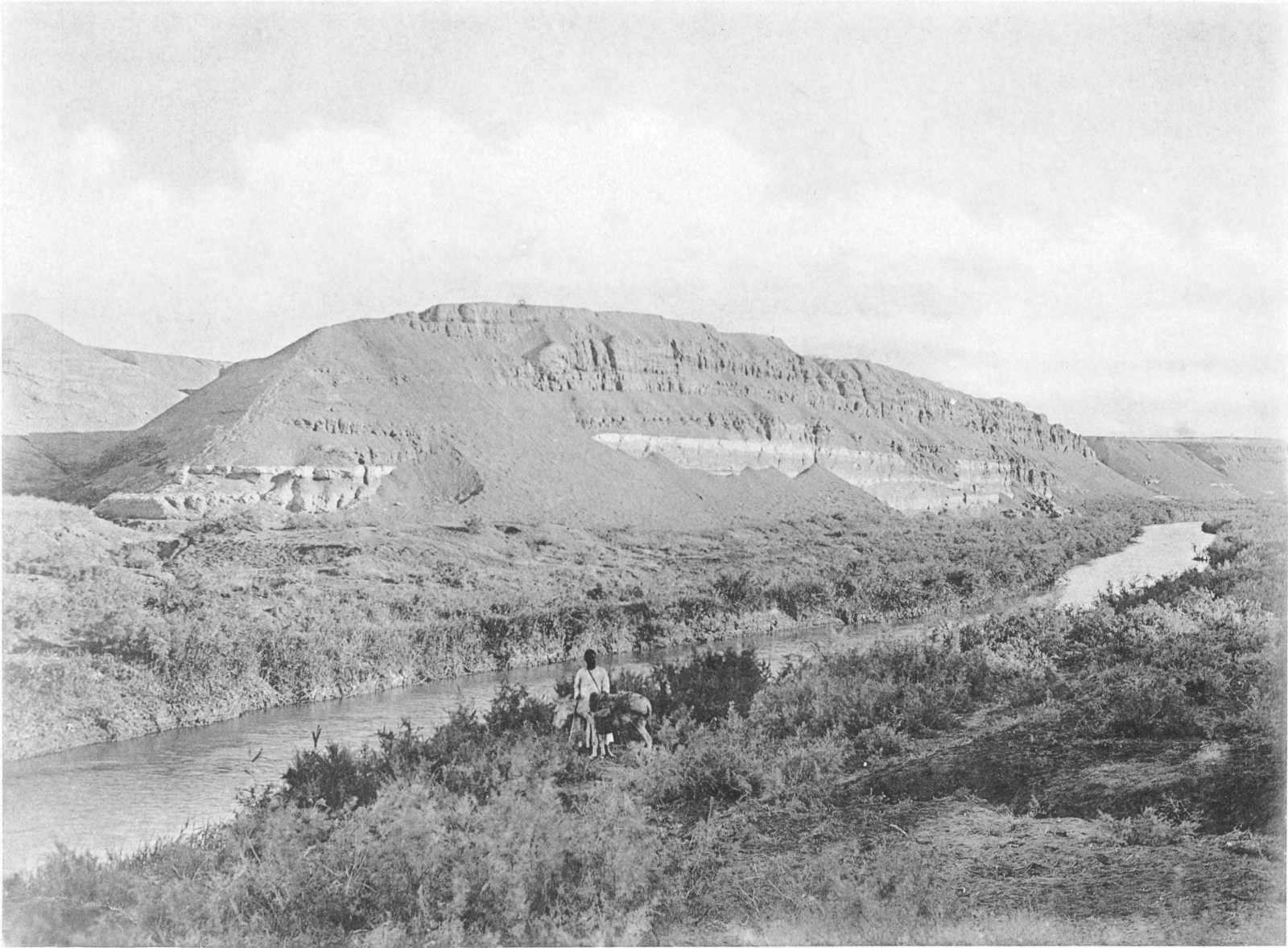

| III. — | El Wadi, Ravine near Qasr Gebali | „ | 19 |

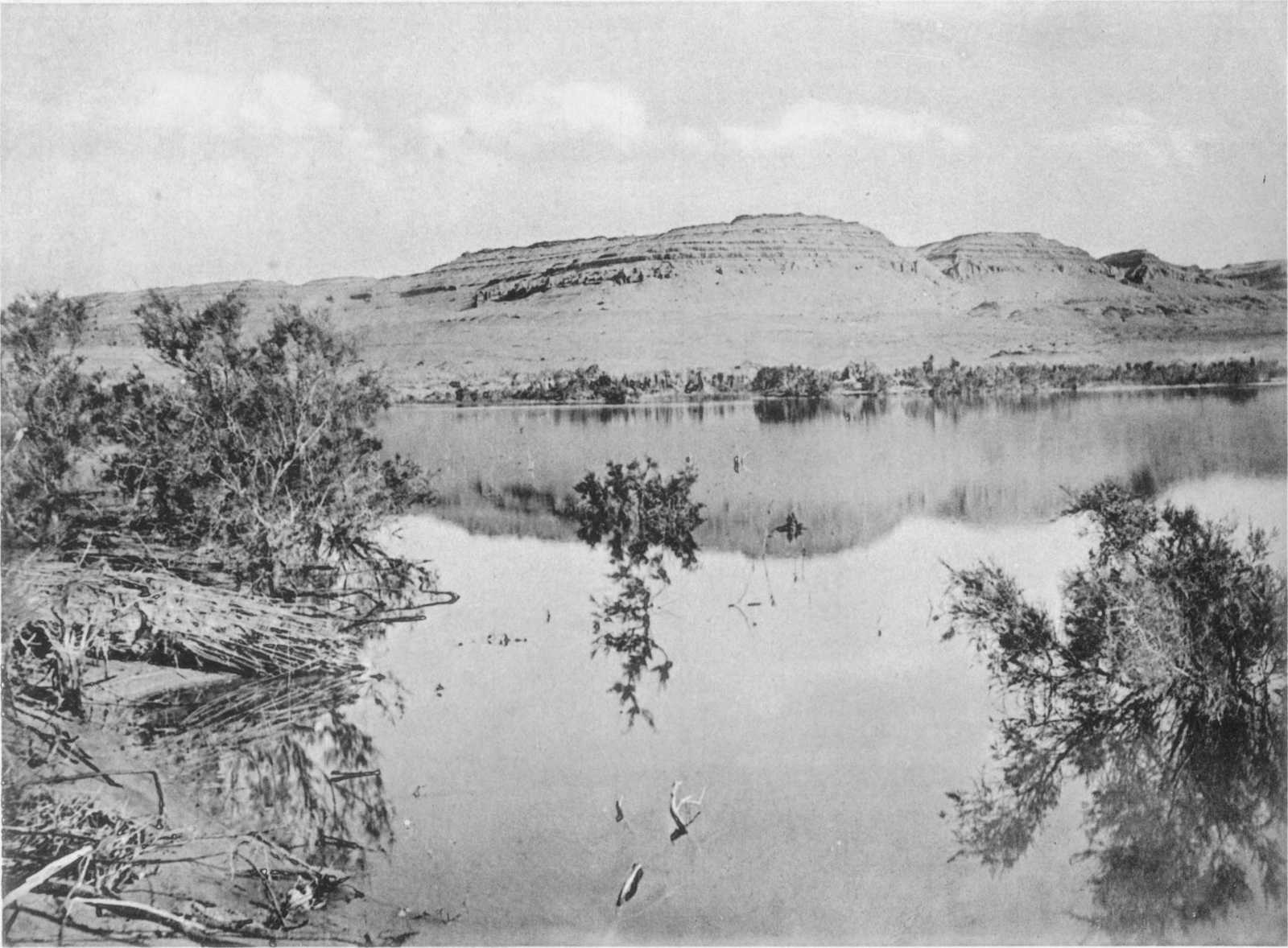

| IV. — | Western extremity of the Birket el Qurûn | „ | 29 |

| V. — | Alluvial deposits overlying marly limestones (Ravine Beds) in El Wadi, Ravine near Qasr Gebali | „ | 37 |

| VI. — | Escarpment of the Birket el Qurûn series near the western end of the lake | „ | 41 |

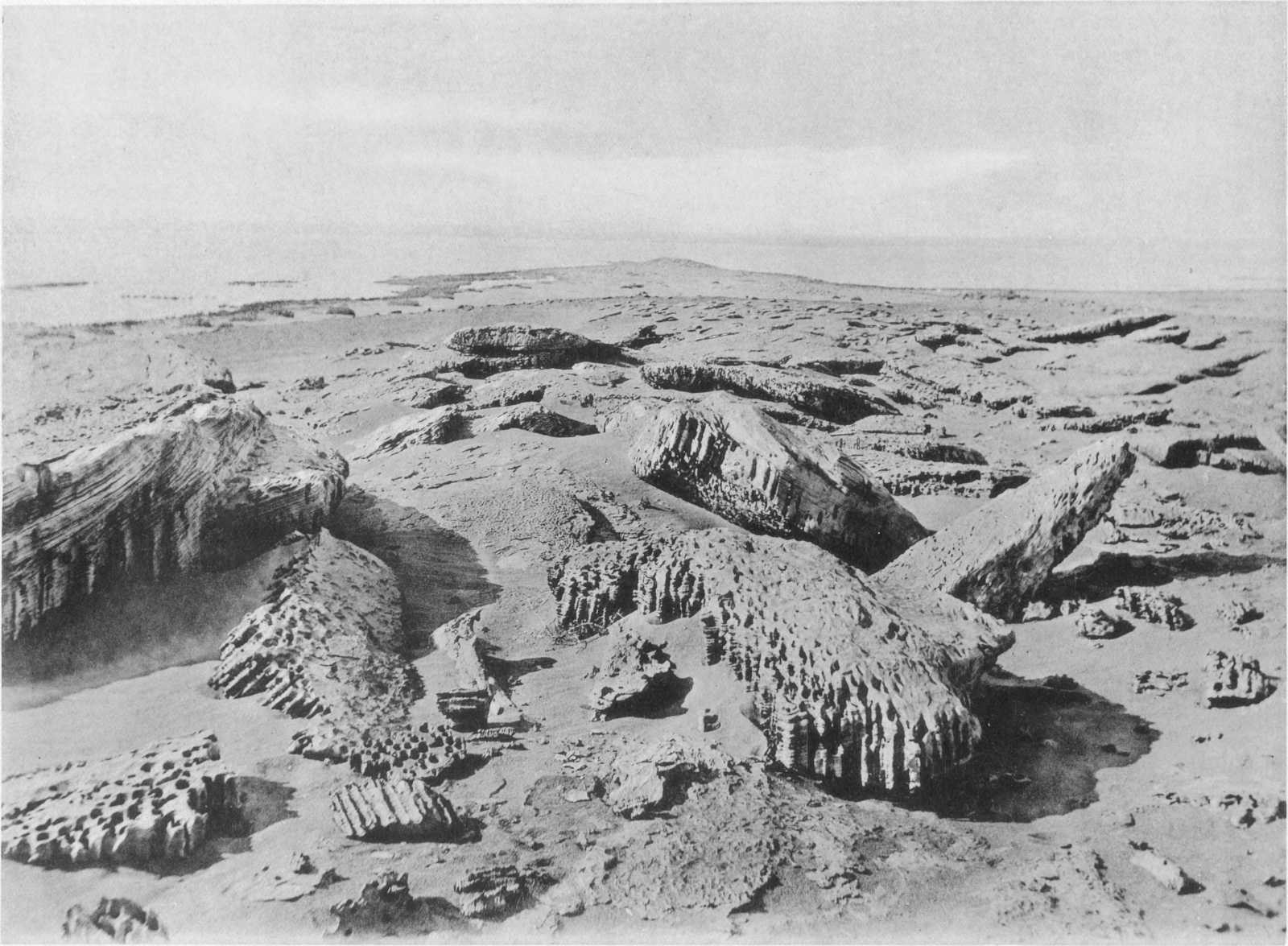

| VII. — | Weathered concretionary sandstone (Birket el Qurûn series) on north shore, near Geziret el Qorn | „ | 45 |

| VIII. — | Middle Eocene escarpment (Qasr el Sagha series) 12 kilometres west of Qasr el Sagha | „ | 49 |

| IX. — | Upper beds of Fluvio-marine series with basalt cap, looking west from the eastern extremity of Jebel el Qatrani | „ | 53 |

| X. — | El Qatrani range from the south-east | „ | 57 |

| XI. — | Silicified trees of Fluvio-marine series, 4½ kilometres north of Qasr el Sagha | „ | 63 |

| XII. — | Raised Beach unconformably overlying Middle Eocene limestones (Birket el Qurûn series) in the desert east of Sersena | „ | 69 |

| XIII. — | Borings in false-bedded sandstone, 2 kilometres south of Dimê | „ | 73 |

| XIV. — | Pleistocene lacustrine clays with tamarisk stumps in situ at 50 metres above the present surface of the Birket el Qurûn | „ | 77 |

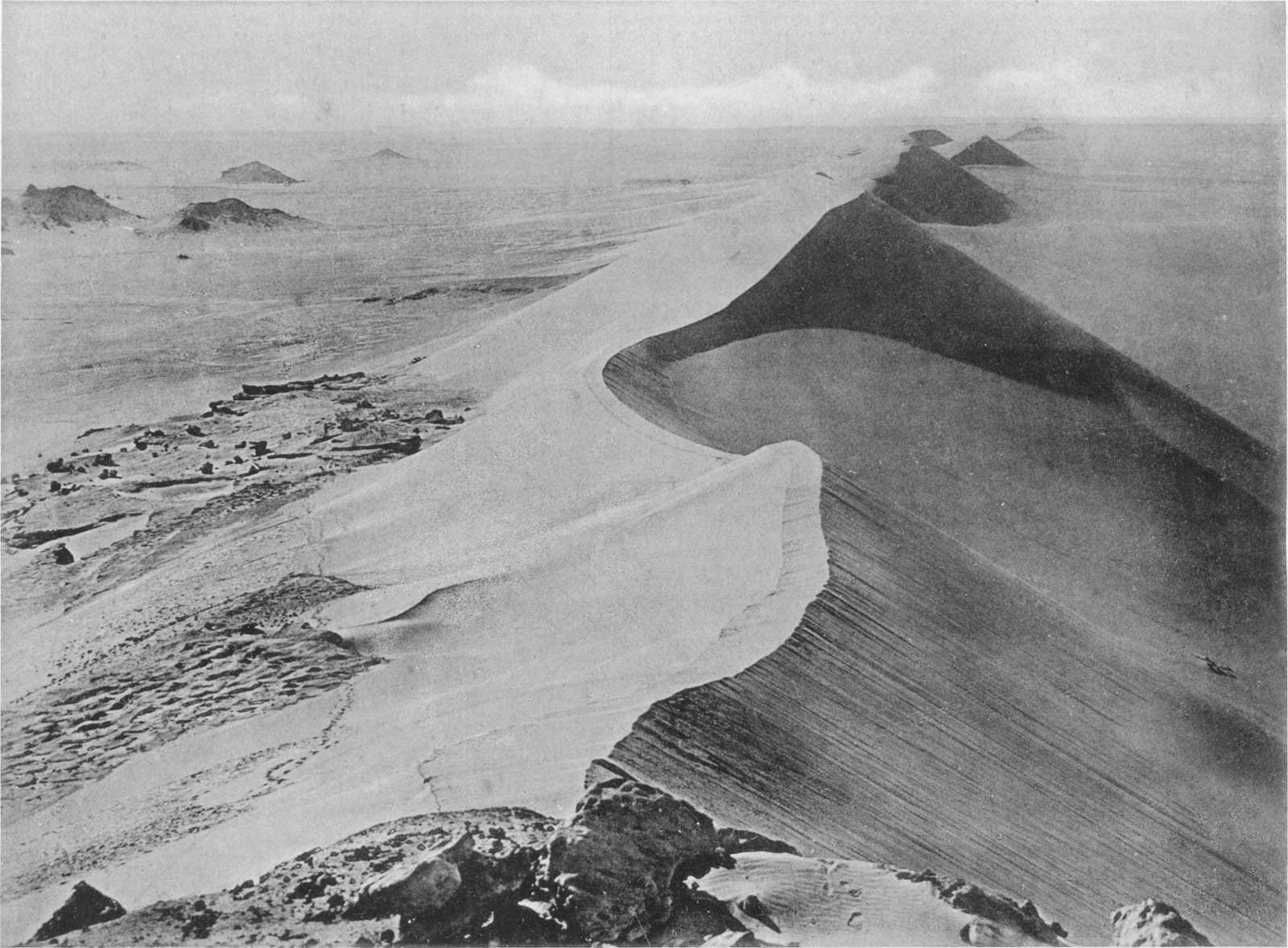

| XV. — | Isolated sand-dune near Gar el Gehannem | „ | 81 |

| XVI. — | The Birket el Qurûn near the western end | „ | 85 |

| PLANS. | |||

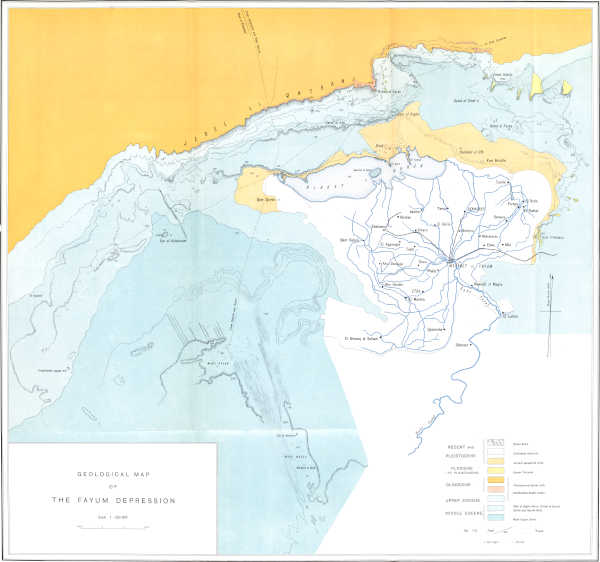

| XVII. — | General Map of the Fayûm depression, with Wadi Rayan and Wadi Muêla, 1250000 | end | |

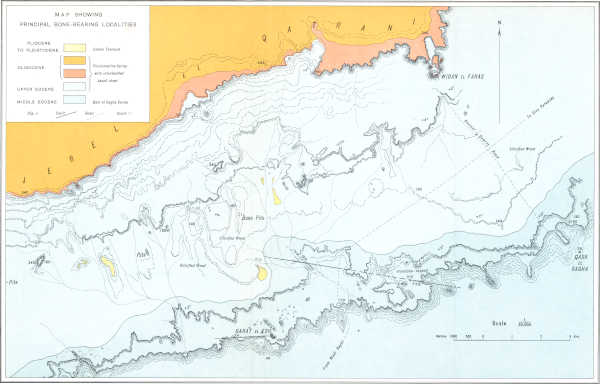

| XVIII. — | Map of the area north-west of Qasr el Sagha, showing principal bone-bearing localities, 150000 | „ | |

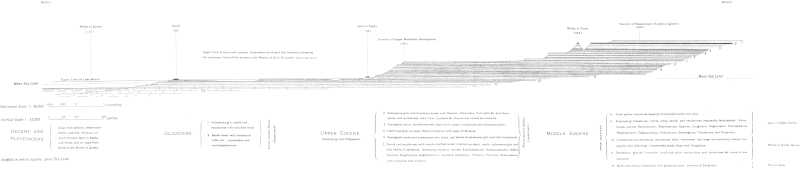

| SECTIONS. | |||

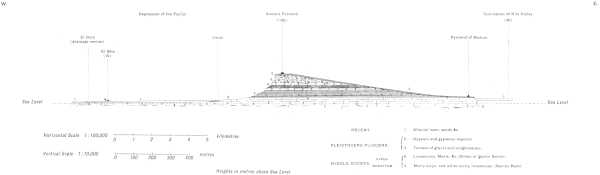

| XIX. — | From the Birket el Qurûn through Dimê and Qasr el Sagha to the summit of Jebel el Qatrani | end | |

| XX. — | From Wadi Rayan to the summit of the escarpment north of Gar el Gehannem | „ | |

| XXI. — | The Desert Ridge separating the Nile Valley and the Fayûm | „ | |

| XXII. — | From Sidmant el Jebel in the Nile Valley through Medinet el Fayûm to the summit of Jebel el Qatrani, near Widan el Faras | „ | |

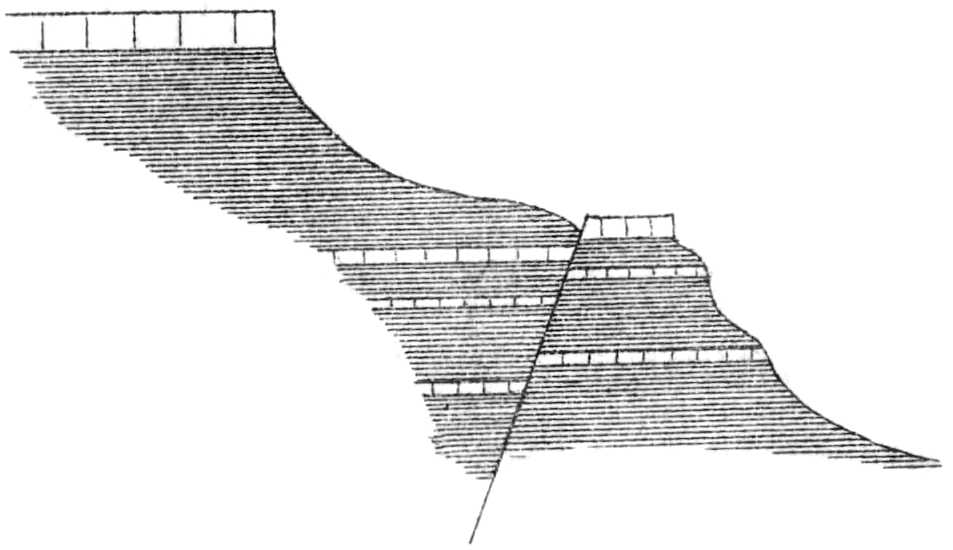

| XXIII. — | Middle Eocene escarpment near Qasr el Sagha | „ | |

| XXIV. — | From Garat el Esh to summit of Jebel el Qatrani | „ | |

| FIGURES (in the text.) | |||

| 1. — | Fault near Qasr el Sagha | 32 | |

| 2. — | Section at Gar el Gehannem, showing the relation of the Wadi Rayan series to the Ravine Beds | 38 | |

| 3. — | Sketch-section across El Bats, one kilometre west of Sêla | 40 | |

| 4. — | Profile of beds of Geziret el Qorn | 44 | |

| 5. — | Section of cliffs, western end of the Birket el-Qurûn | 47 | |

| 6. — | Probable course of chief river of Upper Eocene and Oligocene times | 67 | |

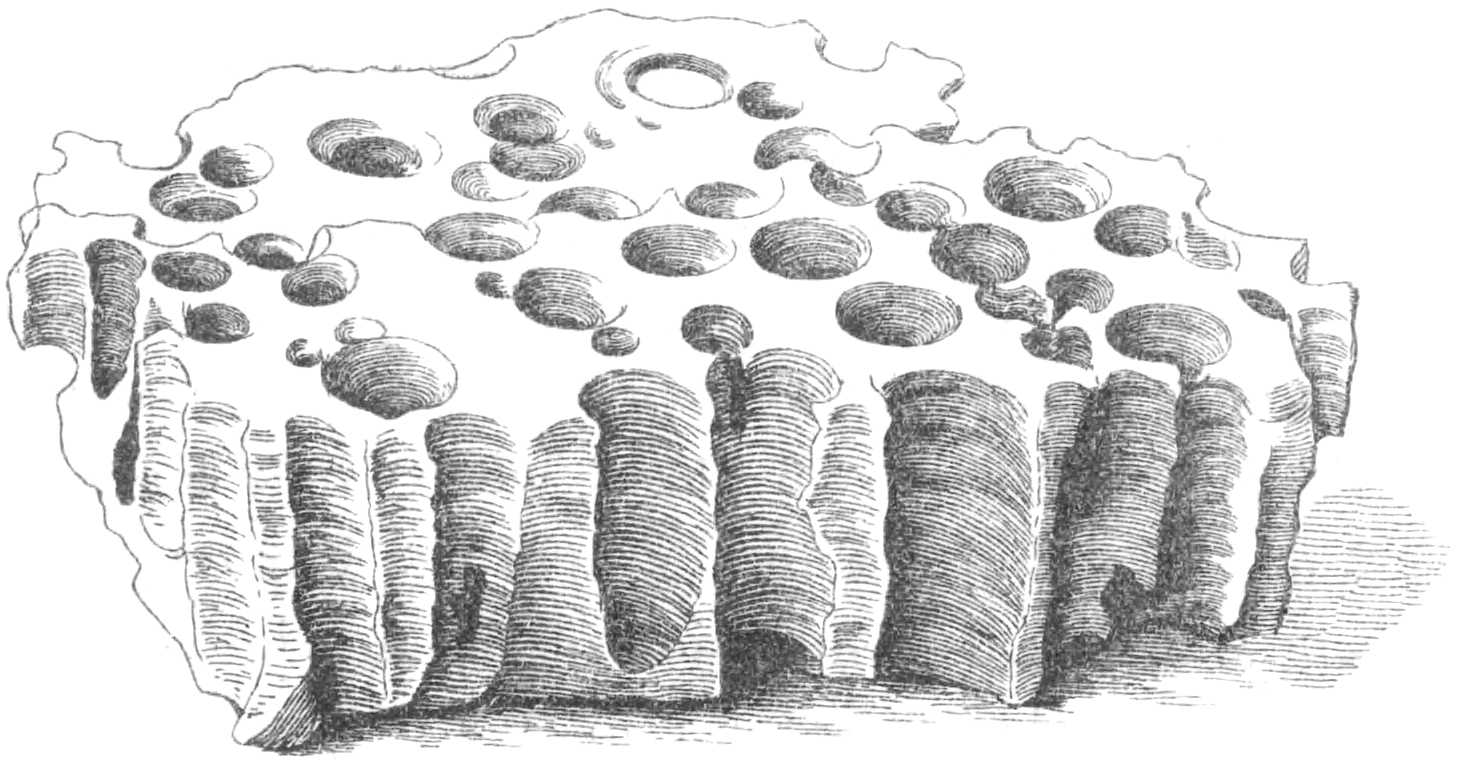

| 7. — | Block of sandstone pierced by numerous borings | 72 | |

| 8. — | Sketch showing relations of the Eocene to Pliocene gravel terraces on the east side of the Fayûm | 74 | |

| 9. — | Sketch-section through the summit of the Fayûm escarpment at Elwat Hialla | 76 | |

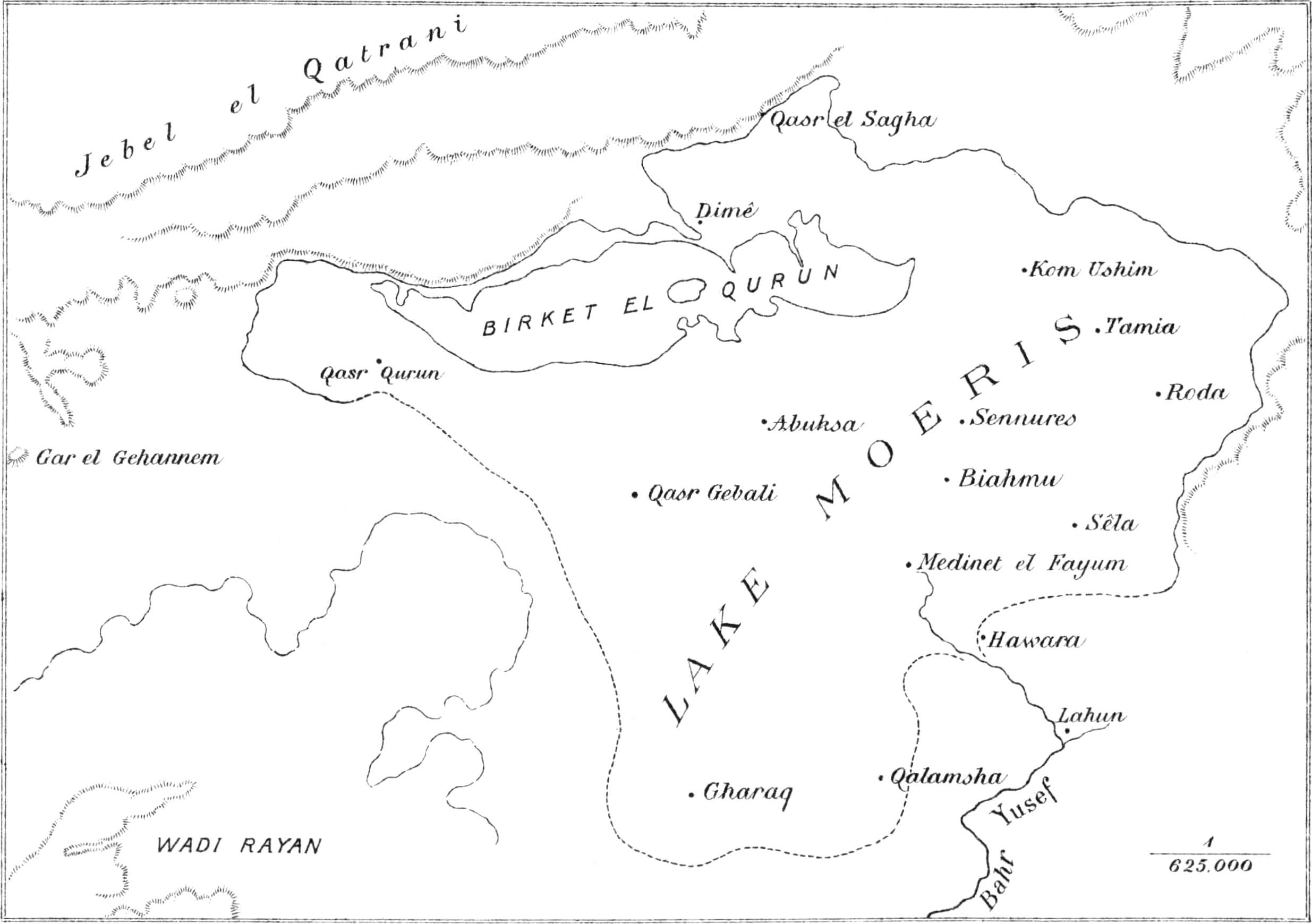

| 10. — | Sketch-map showing approximately the site of Lake Mœris | 83 | |

[9]INTRODUCTION.

The geological survey of the desert surrounding the Fayûm was commenced in October 1898. At that time the area, although so near to Cairo, was little known; the Rohlfs Expedition maps marked the region as “unexplored,” and in fact with the exception of a publication by Schweinfurth, who had traversed the region from north to south, via Qasr el Sagha and Gar el Gehannem to Rayan, there was little information obtainable. The area being of considerable size (12,000 sq. kilom.) and almost unexplored, both geologically and topographically, the primary object was to construct as rapidly as possible a general map of the depression, at the same time laying down in broad outline the chief geological formations and trusting to future opportunity to examine in more detail places of special interest.

Commencing work at Sêla, on the eastern side of the depression, the survey was carried northwards along the east side of the cultivated lands and thence through the northern desert, up to the summit of the depression. After mapping westwards as far as the isolated hill-mass of Gar el Gehannem the work was temporarily suspended until, in the spring, the narrow defile of Wadi Muêla, and the Wadi Rayan, forming the southern part of the Fayûm depression, were provisionally examined.

In January 1901, samples of soil and water from the cultivated lands were collected as an experimental soil-survey, and the results have been published.[1]

During the winter’s work of 1902-03 a traverse was carried from Gar el Gehannem in a south-west direction through a hitherto unexplored part of the depression. On reaching a point midway between Cairo and the oasis of Baharia a connection was made eastwards to Wadi Rayan. In the winter of 1903-04 further exploration was carried out in the neighbourhood of Gar el Gehannem.

It will be convenient here to briefly relate the history of the discovery of the remarkable series of new and extinct animal forms, the recovery of which from the Fayûm deposits has created such widespread interest in the zoological world. When Schweinfurth crossed the region in 1879 he obtained fossil bones, which were examined and determined by Dames to be the remains of cetacea of the genus Zeuglodon, from certain beds of the escarpment west of Qasr el Sagha; these, it is believed, were the earliest vertebrate remains obtained from the Fayûm. During the early part of the survey of the district, remains of fish and crocodiles were frequently found in one of the beds of the Middle Eocene, probably on the same horizon as that from which Schweinfurth had collected. Fragments of bone were also commonly met with on a much higher horizon (i.e., near the base of the Fluvio-marine series) but nothing of particular interest was obtained, as no detailed search could[10] be made at that time. In April 1901, during the survey of the western end of the Birket el Qurûn, some of the localities found to be bone-bearing in 1898 were re-visited in company with Dr. C. W. Andrews, who was in Egypt at the time and had accompanied the survey in order to obtain specimens of jackals, hares, etc., for the British Museum, in connection with the forthcoming work on Egyptian mammals. In one of these Dr. Andrews picked up several vertebrae which turned out to belong to a new species of Pterosphenus.

Further north, when descending the Middle Eocene escarpments at a place not previously examined, we crossed the outcrop of the bone-beds at a point where a considerable number of mammalian and reptilian bones lay exposed on the surface, many in an excellent state of preservation. The importance of the find was evident, and a short examination of the material on the spot enabled Dr. Andrews to pronounce the discovery to be of the highest importance from a palaeontological point of view.

Some three weeks’ work in the immediate neighbourhood resulted in a very good collection of vertebrates from the Middle Eocene beds, including several new genera afterwards described[2] under the names of Eosiren, Barytherium, Mœritherium, Gigantophis, etc. Moreover, a fossil tooth brought in by one of the camelmen from a point several kilometres to the north led to a careful examination of the lower beds of the overlying Upper Eocene formation, which resulted in obtaining well-preserved remains belonging to a new genus, since described as Palaeomastodon. All the material so far obtained was taken home to be worked up and determined at the British Museum and a preliminary description was published by Dr. Andrews in the Geological Magazine.

In the winter of 1901-02 the survey of the Fayûm was resumed with the special intention of following up the highest beds, those in which Palaeomastodon had been found. Continued search westwards eventually led to the discovery of the remains of a large and remarkable horned ungulate (Arsinoitherium), a preliminary notice[3] of which was published in the spring of 1902. Shortly after, the remains of several new smaller mammals and reptiles (Phiomia, Saghatherium), including the shell of a large land tortoise (Testudo Ammon), were obtained[4]. Further work in the winters of 1902-03-04 led to a great deal more material being obtained[5], mostly of course belonging to the same species, but including some new genera Geniohyus, Megalohyrax, Pterodon.

The amount of palaeontological material is now so large that the Egyptian Government has arranged with the Trustees of the British Museum for the publication of the whole in a monograph to be issued by the Trustees. The present report, therefore, deals only with the geology and topography of the district.

[1]A. Lucas, A preliminary investigation of the Soil and Water of the Fayum Province; Survey Dep., P.W.M. Cairo, 1902.

[2]Andrews, Extinct Vertebrates from Egypt. Parts I and II. Geol. Mag. N. 8. Dec. IV, Vol. VIII, Sept. and Oct. 1901, pp. 400-409 and 436-444.

[3]Beadnell, A Preliminary Note on Arsinoitherium Zitteli, Beadn. Survey Dept. P.W.M., Cairo, 1902. See also A New Egyptian Mammal (Arsinoitherium) from the Fayûm. Geol. Mag. N.S. Dec. IV, Vol. X. Dec. 1903, pp. 529-532.

[4]Andrews and Beadnell, A Preliminary Note on Some New Mammals from the Upper Eocene of Egypt. Survey Dept. P.W.M., Cairo, 1902.

[5]Andrews, Notes on an Expedition to the Fayûm, Egypt, with Description of some New Mammals. Geol. Mag. N.S. Dec. IV, Vol. X. Aug. 1903, pp. 337-343. Also Further Notes on the Mammals of the Eocene of Egypt (Parts I, II, III). Geol. Mag. N.S. Dec. V., Vol. I. March, April, May 1904.

[11]PART I.

TOPOGRAPHY AND STRUCTURAL GEOLOGY.

The Fayûm, a large circular depression in the Libyan Desert, is situated immediately west of that part of the Nile Valley lying between Kafr el Ayat and Feshn (Plate XVII.)

The depression, which has an area, roughly speaking, of 12,000 square kilometres, is primarily divisible into three distinct parts—cultivated land, lake, and desert.

Section I.—CULTIVATED LAND.

The cultivated land has an area of about 1,800 square kilometres and, with the exception of the lake and part of the Wadi Rayan, occupies the lowest part of the depression. Cultivation is necessarily strictly limited to the area covered with alluvial soil. The latter, for the most part identical in origin and composition with the river-alluvium of the Nile Valley, covers a leaf-shaped tract between the bounding desert on the east side and the lake (the Birket el Qurûn) on the north-west. The easterly and central part of the cultivated area forms a more or less level table-land, from which the ground slopes gently away, especially on the north side, where the slope is towards the lake and very marked. The cultivated land of the Fayûm is directly connected with that of the Nile Valley by a narrow strip of low ground, a natural passage through the desert separating the Nile Valley and the depression of the Fayûm. Through this gap runs the natural canal known as the Bahr Yusef, which is practically the sole source of water in the Fayûm and irrigates the entire district.

The canal leaves the Nile Valley at Lahûn (Plate II), and follows a somewhat serpentine course through the desert for about 5 kilometres, irrigating a narrow strip of land on either side, which at Hawara rapidly broadens out into the wide cultivated area of the Fayûm. Once within the latter, the Bahr Yusef gives off numerous subsidiary canals which traverse the country in all directions, constantly splitting up into smaller branches until the water-supply is divided throughout the whole area. With the exception of the self-contained basin of Gharaq, on the south side of the Fayûm, the entire district drains into the Birket el Qurûn, which occupies the lowest part of the depression, to the north of the cultivation. The basin of Gharaq is irrigated by the Bahr el Gharaq, a canal which takes off from the Bahr Yusef soon after the latter enters the Fayûm[6].

[12]The cultivated land of the Fayûm is traversed by two main ravines, cut down in many places to the Eocene limestone below the alluvium (Plates III and V.) At the present time these ravines carry canals for irrigating the lower parts of the district, and also act largely as drains to the higher lands. They were probably initiated by the escape of water through breaches in the Bahr Yusef during flood time, and have since been deepened to their present dimensions.

In addition to the main central cultivated area, the soil of which, as mentioned above, is essentially identical with that of the Nile Valley, large tracts of the surrounding country, more especially on the north, north-west, and west sides, are also covered with alluvial deposits. These latter, which include sands, sandy clays, and clays of a quite distinct type, represent the slowly formed accumulations of the quieter and more remote parts of the ancient Lake Moeris (and the earlier prehistoric lake). The material was mostly derived from the Eocene strata which formed the shores of the lake, augmented no doubt by a certain amount of very fine sediment drifted from the Bahr Yusef, and by sand blown in by wind.

It is noticeable that the thickest and most sandy deposits occur near the borders of the lake site; when close under the Eocene cliffs, as along the north side above the Birket el Qurûn, the deposits closely resemble those of the latter. The finer more calcareous beds occur further out and the true marls were accumulated only at some distance from the shores of the lake.

When in Ptolemaic times the lake became reduced to a fraction of its former size, large areas covered by these lacustrine clays were exposed and some portions were brought under cultivation. Subsequently, however, all these outlying districts were abandoned and became absorbed by the surrounding desert, until in modern times the cultivation was restricted to the central portion of the old lake bed, a portion almost identical with the area over which true “Nile Mud” had been deposited.

The construction during recent years of extensive irrigation works in the Nile Valley has made it possible to largely augment the water-supply of the Bahr Yusef to the Fayûm. High level canals are being cut in various parts of the district and already large areas of desert covered by these lacustrine deposits have been brought under cultivation, notably to the north of Tamia and in the neighbourhood of Qasr Qurûn. The approximate area covered with lacustrine deposits can be seen on the map and with a sufficiency of water probably the greater part of this area could be utilized, though the exact value of the soil compared with Nile deposit remains to be determined.

Section II.—THE BIRKET EL QURUN.

The lowest part of the depression, lying immediately to the north-west of the cultivation, is occupied by a sheet of water of considerable size, known as the Birket el Qurûn.[7][13] The lake, which has a length of 40 kilometres, and a maximum breadth under ten, covers at the present time an area of about 225 square kilometres. Sir Hanbury Brown obtained no sounding exceeding 5 metres in crossing the lake to Dimê, but according to the fishermen the depth increases towards the south-west.

Its long axis lies nearly east and west, and while on the north it is entirely[8] bordered by desert, along a large part of the south side the cultivated land approaches its shore, although even here a large area actually bordering the lake is waste salty land as yet unfit for cultivation. As already mentioned, with the exception of the Gharaq basin, the lake receives the whole drainage from the cultivated lands.

The Birket el Qurûn is the existing remnant of the ancient prehistoric lake which covered a large part of the floor of the Fayûm depression, and which in historic times was converted into an artificially controlled sheet of water—the celebrated Moeris—by Amenemhat I and his successors in the XII Dynasty.

Lake Moeris, being used as a regulator of excessively high and low Nile floods,[9] was of the greatest importance in connection with the irrigation of the Nile Valley. In more recent times, apparently under the Persians or Ptolemies according to Flinders Petrie,[10] Lake Moeris ceased to perform its function of regulator; since that time all water, except that required for irrigation of the reclaimed land, being carefully excluded, the surface of the lake has continually and gradually sunk to its modern dimensions.[11]

Lacustrine deposits, showing approximately the actual limits of the ancient Fayûm lake, can be traced over wide areas of now barren desert; these will be more fully dealt with later. The present lake-level is still continually sinking owing to an improved system of irrigation, by which a constantly decreasing amount of waste water drains into the lake. Its average annual fall has, during the last decade, been nearly half a metre,[12] and the slope of the land being very gradual, large areas have been reclaimed during the last few years, though whether the advantages derived from this constant lowering of the lake are not more than balanced by certain drawbacks is somewhat doubtful.[13]

With the new areas now being brought under cultivation the amount of drainage water finding its way into the lake will increase and the fall be checked. At the beginning of 1904 the level was markedly higher than in the previous winter, and a difference of even half a metre alters the shore line to a considerable extent, owing to the flatness of the land by which the lake is for the most part bounded.

Although under the present desert conditions practically no material from the surrounding desert is washed into the lake, doubtless a considerable amount of fine dust and sand is carried into it by the wind, especially during the violent sandstorms which occur frequently[14] in the locality. The high cliffs which bound the northern shore of the lake throughout a portion of its length probably have the effect of checking the velocity of both north and south winds, thus causing a considerable amount of sand, which would otherwise be carried across, to be dropped on its surface. This material, together with the fine mud brought down by the canals on the cultivation sides, must have an appreciable effect in raising the level of the bed of the lake.

The phenomenon of the extraordinary freshness of the water of the Birket el Qurûn has been commented on by Schweinfurth, who shows that the degree of concentration of salt in a lake whose volume has been continually reduced, and to which salt has constantly been added, should be many times greater than the actual existing amount. An analysis[14] of the water at the west end of the lake (where the concentration is greatest, owing to the distance from the feeder canals) showed that the total salts amounted to only 1·34%, of which 0·92% was sodium chloride. Dr. Schweinfurth[15] concludes that the lake has a subterranean outlet, which alone would enable it to maintain its comparative freshness.[16] In this connection it is interesting to note the existence of distinct currents, which may possibly be caused by such outlets, in certain localities on the north side of the lake; and it is just possible that a careful survey of the lake itself would not only prove the existence, but show the exact position, of such underground outlets.

Most probably, however, the currents are simply local movements produced by temporary differences of level, which might conceivably be caused in such a large and comparatively shallow sheet of water, varying considerably in salinity in different localities, by wind and evaporation.

The comparative freshness of the lake and the possible presence of underground outlets are of the highest importance in their bearing directly on two of the most important questions in connection with the proposed utilization of the Wadi Rayan as a reservoir, i.e. what the leakage from such a reservoir would be and to what degree of salinity its water would attain.

Section III.—THE SURROUNDING DESERT REGION.

With the exception of the lake and the cultivated area the depression is practically entirely desert. The southern and south-western parts include the wadies Rayan and Muêla, where freshwater springs occur, surrounded by areas covered by a good deal of wild scrub. Apart from these, however, no springs occur outside the cultivated land.

The topography of the region is so intimately connected with its geological structure that an adequate description of the former is not possible without constant reference to the latter. Full geological details will, however, be reserved for later consideration.

[15]Area and Limits.The part of the Libyan Desert dealt with in this report has, excluding the cultivated land and the lake, an area of some ten thousand square kilometres. While some portions have been examined and mapped in detail, others are still very imperfectly known, especially on the south and south-west sides. The irregular cliff-line forming the southern boundary of Rayan and the adjacent wadis may be taken as our limit in this direction, beyond lying an almost unbroken limestone plateau rising gradually and continually to the south. On the north and north-west the area under description is bounded by the southern limit of the great undulating high-lying gravelly desert-plateau which stretches with little change of character to the Mediterranean. On the east side the Nile Valley forms a convenient though not altogether natural boundary; while to the south-west our limit practically coincides with the boundary of the depression, where the floor of the latter insensibly merges into the general desert plateau.

Rocks forming the Area.The rocks forming the area within the above limits are almost entirely of sedimentary origin, the exception being a band of hard basalt intercalated at the very top of the series and exposed only on the extreme northernmost limit of the depression. The total thickness of sediments, from the lowest beds exposed in the bottom of the Wadi Rayan to the summit of the escarpments, a day’s march north of Tamia, is some 700 metres. These beds include every kind of sedimentary deposit—limestones, marls, clays, sandstones, sands and gravels, forming an ever-changing succession of rocks, varying considerably in hardness and capacity for withstanding the agents of denudation. It is not too much to say that the coming into existence of the Fayûm, with its plains, lowlying depressions, precipitous cliffs and escarpments, was largely dependent on the existence of this variable series of deposits.

Apart from the presence of sediments varying greatly in hardness and durability, the fact that the whole of the rocks have an almost constant northerly dip of two or three degrees is a point of prime importance. So small a dip may be scarcely noticeable in any one place, but over the large areas with which we have to deal its influence on the position and level of any individual bed is very marked and the topography of the region would have been essentially different if the strata had been quite horizontal.

Origin of the Fayûm.The unique character of the Fayûm is alone sufficient to show that special causes have acted in its production. Two main causes stand out:—(1) the presence of thick bands of comparatively soft arenaceous and argillaceous strata breaking up the usually continuous hard limestone of the Middle Eocene; (2) the effect of the Nile Valley fault in lowering the whole of the western desert (north of Assiut) relatively to the eastern. The former took place as the result of changed geographical conditions on the continent to the south at the time in question, with which however we need not deal here. On a homogeneous mass of rock weathering has little power to form depressions of any magnitude, and this is the cause of the continuous unbroken plateau which stretches southwards from the Fayûm, the underlying rocks being one continuous thick mass of hard limestone. Wherever softer intercalations[16] are present differential weathering takes place, and all the great depressions of the Libyan desert owe their origin to the presence of soft easily denuded strata; if the great homogeneous mass of Nile Valley limestone had stretched unchanged westwards, the oases of Farafra and Baharia would never have existed. They owe their origin entirely to the presence of the underlying saddle of softer Cretaceous rocks. Similarly if changed conditions had not led to the deposition of soft beds of clay, marl, and sandstone, the western plateau would have continued unbroken northwards.

A comparison of the two sides of the Nile Valley between Cairo and Assiut shows that the tectonic movements, which largely determined the existence of the valley itself, resulted in a considerable lowering of the rocks forming the western side. This was brought about by differential movements along the north and south line or lines of fault, and by the presence of an east to west monoclinal fold which is especially well marked in the neighbourhood of Heluan. The depressions of the Fayûm would doubtless have existed irrespective of this general lowering of the western desert relative to the east, but denudation would have required an additional period of many thousands of years before the floor of the depression was low enough to allow of its actual connection with the Nile river.

As it has been maintained that the Fayûm is an area let down and enclosed by faults, it may be mentioned here that all available evidence points in an opposite direction; this question of faults will however be dealt with in detail later. The influence of the Nile Valley fault has been explained above and it must be remembered it is one affecting not the Fayûm alone but the northern part of the western desert as a whole.

For purposes of description it will be convenient to divide the whole region into three parts: first, the southern portion, including the wadis Muêla and Rayan; secondly, the central area, comprising the extensive plain forming the floor of the depression as a whole, and including the areas under cultivation and the Birket el Qurûn, as well as the desert separating the Fayûm from the Nile Valley. Thirdly, the northern portion, embracing all the rising ground between the floor and the northern rim of the region. These areas will now be taken in order.

Section IV.—WADI RAYAN AND NEIGHBOURHOOD.

This part of the Fayûm is of special interest in consequence of its possible future as a reservoir. Although the area has not yet been examined in detail by the Geological Survey it will be useful to bring together all the information that is at present available.

Colonel Western’s Survey.In 1882, as a counter-project to other irrigation schemes, Cope Whitehouse suggested[17] utilising as a reservoir the Wadi Rayan, a depression which had been referred to by Linant de Bellefonds.[18] At the request of Sir Colin Scott Moncrieff the Government deputed Colonel Western to make plans of the Wadi Rayan and surrounding country and to ascertain[17] the capacity of the depression and its capability of being used as a reservoir. Liernur Bey under his direction prepared a contoured map, and Colonel Western’s report, plans, and estimates were published.[19] Some general details of the wadi and surrounding hills are given and the detailed survey showed that the 30 metre contour line (above sea-level) enclosed an area of 706 square kilometres (170,000 feddans). The lowest points of the depression were found at 42 metres below sea-level. The sand, scrub and springs are briefly referred to and the discharge of the latter is given as equal to that of a very slow-going four inch hand pipe, the water running out at about + 20 m. and disappearing in the sand. Wadi Muêla was found to be separated from the Rayan depression by sandhills and rock at a mean level of + 50 metres, the lowest point in Muêla being at + 25 metres. A line of levels was run from Rayan through Muêla to the Nile Valley, the highest point crossed being at + 105 metres; for fifteen kilometres the level was not below + 75 metres. In order to find the most suitable passage for a canal to connect the Nile with the Wadi Rayan two lines of level were made after a reconnaissance of the hills near Sidmant el Jebel: the southern, from Ezba Menesi Ali, near the Gharaq canal, to Mazana on the Bahr Yusef, being considered the best. Along this line the highest point was only at + 44·7 metres and the average + 35 metres along four kilometres. Borings were not made here but judging from the surface excavation would be mostly in soft limestone, sand, and conglomerate. A much shorter route is from Deshasleh on the Bahr Yusef over the hills about 5 kilometres to the south of Mazana or Sidmant into the Wadi Gharaq, a distance of 30 kilometres. This route was not however levelled but is fairly straight and apparently not much higher than the Mazana passage.

The survey of the + 30 metre contour line of the Wadi Rayan proved that there were only two outlets into the Fayûm, both on the northern side: these two openings are only from 400-500 metres wide and their lowest points are not below + 25 or + 26 metres.

Later Government Publications by Scott Moncrieff and Willcocks.In 1889 Sir C. Scott Moncrieff published[20] a further note, in which he briefly discussed the probable cost and benefits to be derived from the suggested reservoir, concluding that at least the project was one worthy of being thoroughly examined.

In 1894 the plans and designs in connection with the Wadi Rayan were published[21] and the possibility of utilizing the Wadi Rayan was examined by Sir William Willcocks, then Director General of Reservoirs, from an engineering point of view, and the questions of its probable cost and future utility were discussed. In this report it is stated that the routes proposed by Colonel Western in 1888 pass through salty marls and clays unsuitable for holding canals. Another route is suggested, which after leaving the Nile Valley crosses the high desert ridge in a straight line, passing through the so-called Wadi Liernur (Wadi Lulu of Cope Whitehouse); this depression is 12 kilometres long and has its bed some 24 metres below the general level of the desert. Plate 15 of the report shows the Wadi Rayan, the deserts between it and the Nile Valley and the cultivated land. The map was[18] begun by Col. Western and completed by Willcocks. The lowest point of Wadi Rayan is shown as − 42 metres and the depression is separated from the Fayûm by a limestone ridge generally from + 34 to + 60 metres, except at two places where it falls to + 26 metres above sea level on a length of 600 metres. Within the + 27 metre contour line the wadi has an area of 673 square kilometres and a capacity of 18,743,000,000 cubic metres. Between it and the Nile Valley lie 30 kilometres of desert, of which 11 are occupied by a marked depression discovered by Liernur Bey in 1887. At the extreme western edge of the Nile Valley (here 20 kilometres wide) runs the Bahr Yusef. Comparing the proposed Wadi Rayan reservoir and the ancient Mœris and allowing for a difference of 4·5 metres between the levels of the Nile Valley in B.C. 2,000 and to-day, Willcocks assumes that the high water mark of Lake Mœris was at + 22·5 metres and its area 2,500 square kilometres, against 673 square kilometres of the Wadi Rayan at + 27 metres. It is pointed out that the ancient lake had the great advantage that in those days the Bahr Yusef was an important branch of the Nile, if not the main river itself, and the reservoir was connected with the Nile by a natural ravine of great length and short breadth, across which a massive embankment was thrown and destroyed annually, the surplus water of high floods being stored for the deficiency of low floods.

The published sections along the lines of borings put down show the different strata cut through by the proposed canal. The Nile Valley, along the line of the inlet canal, consists of hard clay 6 to 10 metres thick, lying on coarse sand. Along the outlet canal sandy clays and clays alternate to a depth of 10 metres. On entering the desert sands and sandy conglomerate, with gypsum and salt, are met with below the surface, then a yellow marl with salts, and finally a plastic black clay overlying the Parisian limestone. These beds are most extensive in the narrow neck of land between the Nile Valley and the Fayûm and to some 10 kilometres to the south of it. They rise to + 70 metres. There are some other marls inside the Wadi Rayan or in the adjacent depressions and as they have to be traversed by the canals form a serious factor, being easily dissolved in water; in consequence Willcocks chose the alignment of the inlet canal along the Bahr Belama where the extent of these beds would only be 2·5 kilometres against 9 kilometres on the alternative route marked on the plan. A narrow neck of land, some 15 kilometres in length, runs between the Fayûm and the depressions traversed by the proposed Wadi Rayan canal; this neck is the continuation of the salty marls and clays, but the limestone is near the surface and is overlain by a thin deposit of sand and pebbles, with freshwater shells on its northern slope at + 22·50 metres; the southern slope is entirely devoid of them. Willcocks points out that it is evident the ancient Mœris rose to + 22·50 metres but its water never penetrated into the Wadi Rayan. The report goes into details of inlet and outlet canals, discharge, necessary masonry works, cost, and compares the different reservoir schemes.

After a careful review of the whole question, the scheme, while considered perfectly feasible as far as available data went, was abandoned by Sir William Garstin[22] in favour of the less costly and more useful Nubian reservoir.

[19]Schweinfurth’s report on the probable salt-content in Wadi Rayan Reservoir.In an appendix[23] to the above report Schweinfurth discusses the question as to how salt the water of such a reservoir would become. He points out that the exact valuation of the salt which would be contained in this reservoir when the water had risen to + 27 metres cannot be accurately determined, owing to the absence of information on certain points. The maximum quantity of salt in the desert soil is estimated at 2% and this figure is used in his calculation, which includes the amount of salt which would be brought into the reservoir, (1) from the Nile during filling and in the extra water entering to replace that lost by evaporation in the lake and canals; (2) from the ground forming the bed of the lake (far the largest item); (3) from the bed and banks of the inlet canal, both in the desert and in the Nile Valley; and (4) from infiltration. The figure obtained is 7,500 million kilogrammes, equal to 0·04 per cent, or almost one twenty-fifth per cent of salt. This amount is only equivalent to half the salt existing in many of the well waters used in the country for irrigation. As Schweinfurth is careful to point out his calculation is based on maximum and assumed data.

Willcocks’ “Assouan Reservoir and Lake Mœris”.The question of the utilisation of the Wadi Rayan as a reservoir has recently been again brought to the front, notably by Sir William Willcocks in a paper[24] read before the Khedivial Geographical Society, Cairo. The author, after pointing out the value of such a lake, working in connection with the Assuan reservoir, discusses at length the position, dimensions, and functions of the ancient Lake Moeris. It is suggested that the main canal should be cut through the desert opposite Mazana and crossing the so-called wadis Liernur and Masaigega enter the Wadi Rayan at its easternmost point. These wadis would in time become covered with alluvium and be converted into valuable cultivated land. After examining the big ravines of the Fayûm, where similar beds are exposed, the author comes to the conclusion that the maintenance of canals in the saliferous marls, which form part of the desert through which the inlet canal would pass, would offer no particular difficulties.

With regard to the questions of leakage into the Fayûm and of the water of the lake eventually becoming salted, Sir William Willcocks says, “When the old Lake Moeris, or the present Fayûm, was full of water and 63 metres higher than the bottom of the Wadi Rayan and remained so for thousands of years, there was no question of the waters having become salted or having escaped into the Wadi. The Wadi was as dry as it is to-day and the great inland sea was always fresh.” As to the question of leakage into Gharaq the author considers that if water found its way into that depression it would be a distinct advantage, as such water could be pumped into the Nezleh canal and utilized elsewhere; he maintains at the same time that no leakage will take place. Incidentally it is mentioned that the Wadi Rayan is separated from the Fayûm by a limestone ridge, a statement which, as will be shown later, requires modification.

Wadi Rayan not yet examined in detail by the Geological Survey of Egypt.Until a detailed geological examination of the Wadi Rayan and neighbourhood has been carried out it will not be possible to form reliable opinions on many of the questions raised in connection with the prospective reservoir. The writer’s acquaintance with the area[20] is limited to a traverse in 1899 from the Nile Valley through Wadi Muêla to Rayan and thence to Gharaq, and subsequently to a stay of a few days duration in the neighbourhood of the Rayan springs, after mapping the extreme south-west of the Fayûm depression. While the accompanying maps may be taken as representing fairly accurately the bolder topography of the region, they do not replace the older contoured maps of the floor of the depression and the country between it and the Nile Valley to the east, accompanying the report on “Perennial Irrigation and Flood Protection in Egypt.”

The following description of this part of the district is based on a traverse from the Nile Valley through the wadis Muêla and Rayan to Gharaq; the detailed geological sections measured and examined along the line of route will be given later.

Traverse from Nile Valley through Wadi Muêla to Rayan and Gharaq.Between the village of El Gayat and the mouth of the Wadi Muêla (16 kilometres to the north-west) stretches a gradually rising undulating gypseous plain, superficially covered with loose sand and rounded pebbles of quartz and flint. In occasional small hills the white limestone which forms the underlying rock is visible. Near the entrance to the wadi stands a somewhat prominent conical hill composed of hard whitish fossiliferous limestone passing down into more sandy and clayey beds. The bottom of the wadi is cut out in soft green and brown clays, its surface being covered with blown sand, fragments of limestone, flints and gypsum. From the mouth of the wadi the Nile Valley cliffs run north and south in a winding irregular manner. On entering the valley several outstanding flat-topped limestone capped hills are passed on the right hand; they are in part joined to the regular bounding cliff beyond; the eastern cliff is steep and well-marked, while that on the west only outcrops here and there, buried as it is in immense accumulations of blown sand, rising in places into definite dune-ridges. Wadi Muêla has a length of some 18 kilometres and lies nearly N.W. and S.E. The central part of its floor is a sandy scrub-covered area, the lowest points lying at about + 25 metres; just at the southern edge of the scrub stands a small hill composed of hard shaly clays capped by white limestone, surrounded by a saline, superficially dry. Holes dug in this are at once filled with excessively salt water, and by evaporation of the brine in shallow troughs supplies of white fairly pure salt can be obtained. The area is known as Warshat el Melh in Wadi Muêla.Warshat el Melh. Banks of reeds were found growing on the north side of the saline, the surface of the latter being here composed of a soft brown sandy salty deposit, caking here and there into a hard earthy impure salt.

In the lowest spots the saline frequently consists of soft wet sludge; its area is about half a square kilometre but the depth of the deposit is unknown. In the middle of the scrub-covered area to the north lies Ain Warshat el Melh, a pool of water, fairly fresh and drinkable, although ferruginous, measuring 10 by 5 metres in size and from 2 to 2½ metres deep. The water evidently rises from a spring on the west side, round which are fifty square metres of green rushes, with some larger bushes. The ground around and above is very saliferous; between the spring and the ruins to the north the ground is sandy, with many bushes and much scrub. This ground extends two kilometres[21] to the west, whence it gradually passes up into great masses of drift sand; an occasional small outcrop of the top of the plateau above the sand is all that serves to locate the position of the buried cliff. On the east side the sandy ground with scrub extends about a kilometre, beyond which the plain gradually rises for another kilometre to the base of the cliff beyond, which is fairly steep and well-marked, though with an entire absence of indentations of any kind.

Der el Galamûn.Close to the north end of the valley, and about 33 kilometres from El Gayat, lie the ruins known as Der el Galamûn bil Muêla. At the time of our visit a new square stone building was in course of erection and five or six persons were inhabiting the place. There are several small palms scattered about to the south of the monastery and an excellent running spring of clear water five hundred paces to the south-west. A new well is being sunk within the premises. To the north of the monastery the eastern cliff takes a marked trend to the west for some three kilometres, whence it resumes a northerly direction, always maintaining its character of a steep well-marked escarpment rising some 100 metres above the floor of the wadi. At the corner of the cliffs the lowest bed exposed is a white limestone; this is overlain by gypseous clays passing up into sandy beds, the latter being surmounted by the white limestone capping the escarpment.

Wadi Rayan.We are here on the summit of the divide between Wadi Muêla and Wadi Rayan, the height of the floor being about + 105 metres; to the north stretches a gradually widening bay descending to the lowest ground of the Rayan depression. Immense accumulations of sand almost block the defile and stretch away to the east, and the hitherto well-marked cliff on that side bends back and is lost to view. On the other side however, the bounding wall gradually emerges from the dunes, getting more distinct as it is followed northwards until it becomes quite clear of the sand. The first glimpse of this cliff is seen a couple of kilometres west of the pass in an outcropping headland, the next point visible being some five kilometres further west. Between these portions of the cliff are one or two outliers, surrounded by quantities of blown sand. A depression known as Wadi Korif is reported to lie to the west, and much scrub and some water is said to exist there; such a wadi is marked on Schweinfurth’s map but apparently has not been examined.

Continuing in a N.N.W. direction high rather steep dunes occur on either flank, running N.N.W. and S.S.E. Between the dunes is a fairly hard undulating sand-flat affording an easy route; further on a narrow defile between the dunes leads down to the centre of the depression. The main areas occupied by blown sand are shown in the accompanying maps. The most interesting part of the depression is the bay lying to the south of the narrow well-marked promontory jutting out from the southern plateau, a huge pointer, as it were, in the direction of Gharaq; this is the Cape Rayan of Schweinfurth.

[22]Springs in Wadi Rayan.The bay is on three sides completely enclosed by cliffs and its floor is thickly covered by a luxurious growth of wild scrub—chiefly tamarisk and ghardag; numerous isolated palm trees occur, especially in the neighbourhood of the water which exists at several points. There are three particularly good springs,[25] the positions of which are shown on the accompanying maps. According to Colonel Western’s survey the water emerges at about + 20 metres. In 1899 the water of the northern spring was found to have a temperature of 26°C. On our last visit we found an artificially constructed pool of two metres diameter and a depth of 30 centimetres; on the west side of this were two springs, marked by the motion of the grey sand rising and falling in the vents, down which a stick could be easily pushed to a depth of two metres. The output of these springs together amounted to six litres a minute; the water was quite clear and although soft and rather ferruginous not by any means unpalatable (see analyses below). The pool lies on an open bare sandy spot and is surrounded by scattered bushes, none of which however are within fifteen metres; a sand dune lies 150 metres to the south-west, with bushes and seven or eight young palms. The southerly spring has an output of 21 litres a minute, and its water does not differ essentially from that of the northern spring. Rising at the foot of a palm tree it forms pools on either side; thence it flows a distance of 20 metres into an artificially constructed shallow basin 2 to 3 metres across, from which it runs away down the slope and disappears after five or six metres. The east spring, which is situated on the east side of the dunes bounding the mouth of the bay, consists of a small hole cut out in soft sand. The water seemed good, although analysis shows the salts content to be high; this spring does not run, but if emptied the hole soon refills. The remains of old buildings occur near the well, in the shape of loose roughly squared limestone blocks, broken pottery, and remains of old walls; the latter are nearly level with the ground and very thickly and solidly built.

To the south of the promontory lies the so-called Little Rayan. Here there is a good deal of scrub, and water can be obtained on the lowest ground at a few metres depth, although there do not appear to be any surface springs.

Geology of Wadi Rayan in broad outline.The geological succession of beds exposed in the cliffs of the promontory is given later. Broadly speaking it consists of two thirty-metre bands of hard limestone separated by 68 metres of softer sandy and clayey beds. The lower of the limestone bands in places forms the floor of the depression but more frequently the latter is composed of[23] the overlying sandy or clayey beds. The depression is bounded on the north side by the same succession, and, as far as could be judged from observations made on the traverse, the bed of limestone capping the ridge, and forming the plain stretching away to the Birket el Qurûn and to Gar el Gehannem, is identical with that capping the cliffs to the south, i.e. is the uppermost of the two thick limestone bands. At the two points more particularly noticed, namely, the spurs projecting southwards into the depression, 23 kilometres west and 18 kilometres W.S.W. of Gharaq basin, the sequence seemed to be the same as in the southern cliffs, although, owing to the northerly dip, the upper bed of limestone lies at a much lower level and the basal beds are not exposed at all. In both these localities, however, some of the underlying clays were exposed, as well as on the lowest spots crossed between the most easterly spur (18 kilom. W.S.W. of Gharaq) and the extensive dunes lying immediately west of Gharaq cultivation. These dunes, though of no height, have remarkably steep sides. In crossing Gharaq to the Fayûm cultivation occasional beds of yellow sandy limestone were noticed, but their horizon was not determined. Numerous bored blocks, probably belonging to the marine Pliocene, were observed scattered about. Apparently the uppermost thirty-metre band of limestone passes continuously northwards under the cultivated lands of Gharaq and the Fayûm; in the ravines of the latter this limestone is not observed, the soft limestones exposed below the alluvial deposits almost certainly belonging to the overlying Ravine beds. The country to the east of Gharaq has not been geologically examined and the exact locality in which the thick bed of limestone dips underground and is overlain by the succeeding beds is doubtful. Further north, in the desert ridge east of Qalamsha, we have observed the Birket el Qurûn beds and a section measured at this point is given later.

Character of Ridge separating Wadi Rayan from Gharaq and the Fayûm.As it appears to have been freely assumed that the ridge separating the Rayan depression from the cultivated lands of Gharaq and the Fayûm is formed throughout of solid limestone, it is important to point out that, on our assumption of the identity of the beds of limestone capping the cliffs to the south and the plain to the north of the Wadi Rayan, the dividing ridge would in part be formed of the underlying arenaceous and argillaceous beds.

Question of leakage through dividing ridge.The absence of Nile deposit and freshwater shells in the Wadi Rayan will, when confirmed after a thorough examination of the area, afford the strongest evidence that the depression was never directly flooded by Nile water. The fact that the dividing ridge is probably everywhere above the highest level attained by Lake Mœris, and by the still more ancient prehistoric lake, is almost sufficient in itself as a proof of this. It does not however follow that there was not leakage through the ridge into the Rayan basin, as such leakage might conceivably have taken place to a considerable extent without the water ever having collected in sufficient quantities to form even moderate sized pools within the depression. The bottom of the depression is for the most part covered with soft porous sandy deposits overlying the Eocene bed-rock below, and at the present time the[24] water of the Rayan springs, though continually running, at once disappears from sight, drains down to the lowest parts of the depression and is then gradually lost by evaporation or underground leakage. In the lowest parts of the depression this water is, as already mentioned, met with on digging to a very moderate depth.

A careful examination of the flanks of the ridge separating the Fayûm and Gharaq cultivated areas from Rayan might prove if such leakage ever took place. If such was the case the seepage was probably along the line of junction of the limestone and underlying clayey or sandy beds. Even if it were proved that there never was leakage from Lake Mœris into Wadi Rayan, it would not be safe to assume that the converse would not happen, as the dip of the beds is from south to north and this fact is one to be reckoned with. Judging from the nature of the Eocene beds forming the Wadi Rayan, my opinion is that leakage on a large scale would not take place, and that owing to the northerly dip any water that escaped from the reservoir would pass indefinitely northwards and would not find its way through the overlying limestone to the surface either in Gharaq or the Fayûm cultivation. A detailed examination of the local geology would, however, be necessary to prove or disprove this. As to the question whether the Wadi Rayan as a whole would hold water, as far as is known there are no faults or other fissures of any magnitude through which the water could escape. No doubt a good deal of water would be lost before the smaller joints and passages, which exist in all rocks, were silted up. Schweinfurth supposes that the freshness of the Birket el Qurûn is due to the existence of subterranean outlets, and such might also be found to exist in the Wadi Rayan. In any case the argillaceous deposits from such a lake would very soon form a bed to all intents and purposes impermeable.

Degree of Salinity.With regard to the extent of salinity of such a lake Dr. Schweinfurth’s figures are of considerable interest and value, although based wholly on assumed data. The greater part of the salt would be derived from the rocks and soil forming the bed of the reservoir and only by extensive sample collecting and analysis can reliable figures be obtained. We believe that in the lowest parts of the basin the salt content of the ground would be found considerably in excess of the two per cent used by Schweinfurth in his calculation, although his total estimate would probably be found well within the mark.

Section V.—CENTRAL AREA OF THE REGION.

Central Plain at the Fayûm Depression.The great central plain, forming the floor of the depression as a whole, is composed of a hard bed of limestone some thirty metres thick. This limestone, forming the uppermost member of the Rayan series, is, as already mentioned, almost certainly identical with that capping the cliffs to the south of the depression, and in all probability in the eastern extension of the plain under description underlies the whole of the cultivated lands of Gharaq and the Fayûm. The feature of the plain as a whole is its marked and constant, though low, dip to the north; so that its surface, bared by denudation of the overlying[25] soft limestones of the Ravine series, over a distance of some twenty kilometres, is a true dip-slope, at the base of which lies a strip of low-lying country extending from beyond Gar el Gehannem through the Birket el Qurûn to the Nile Valley ridge east of Tamia. The central and lowest portion of this low-lying area is occupied by the Birket el Qurûn, the bed of which lies fifty metres below sea level and is thus the lowest known spot in the whole of the Libyan desert. Thirty kilometres south-west of the western end of the lake, at the base of the dip-slope of the central plain and immediately under the southern scarps of the great outlying hill-mass west of Gar el Gehannem, lies another low lying basin, which receives the drainage from a considerable area of the plain to the south-west. The latter, consisting of the limestone above-mentioned, is here superficially covered by gravel, and its dark undulating surface is scored by numerous shallow winding water-courses marked by an abundant growth of scrubby vegetation; some of the principal of these drain into the basin just mentioned and after heavy rainfall the water collects and forms a pool 600 metres in length by 100 to 150 metres wide. The base of the basin, at about 80 metres above sea level, is marked by a level deposit of silt of considerable thickness, the east end of the site being surrounded by great numbers of luxuriantly growing tamarisks. Other similar basins exist on the plain to the south, and under an isolated hill five kilometres W.S.W. several full grown acacias were noticed. On the low ground to the north-west of Gar el Gehannem, and at several points between it and the head of the Birket el Qurûn, similar silt covered areas exist, some being only from 30 to 40 metres above sea level.

In the extreme south-west of the region the limestone forming the central plain is gradually overlain by the succeeding beds, so that the ground rises imperceptibly to the level of the plateau separating the depression from that of Baharia, distant some two days march. On the eastern side, if the superficial alluvial deposits could be stripped off, the underlying surface of limestone, sloping from south to north, would not differ materially from the plain further west, except that here, at any rate north of Gharaq, the Rayan limestone is overlain by the basal beds of the Ravine series.

Section VI.—RIDGE SEPARATING THE NILE VALLEY AND THE FAYUM.

The desert ridge separating the Nile Valley from the Fayûm has, to the north of the Bahr Yusef, an average width of some ten kilometres; further south it narrows, until due east of Gharaq the ridge is barely 2½ kilometres wide. The highest points are situated to the east of Sersena and Qalamsha respectively.

In both these localities the Eocene rocks, consisting of clays alternating with beds of calcareous sandstone and sandy limestone (pp. 39, 40) are overlain by thick deposits of conglomerate and gravel, attaining altitudes of over 100 metres above the cultivated land below. From these summits the slope is usually very gradual on the Nile Valley side but much more rapid towards the Fayûm.

The ridge is cut down, however, to a comparatively low level in four localities; to the[26] north-east of Tamia; to the east of Sêla, where the railway crosses; between Lahûn and Hawara, where the Bahr Yusef canal enters; and to the south of Qalamsha, where along the site of the proposed Wadi Rayan canal the highest point is only some 40 metres above the Gharaq basin and 27 metres above the adjoining Nile Valley cultivation.

Outline of earliest connection of Nile with Fayûm.One of the most interesting problems connected with the Fayûm may be briefly alluded to here—When did the waters of the Nile first obtain access to the depression?

As will be shown later the Fayûm was occupied by the sea in Pliocene times, when the great gravel accumulations and gypseous deposits were formed. Later the area became dry and denudation of the land surface completed the work of erosion already begun in earlier times.

In Pleistocene times drainage down the Nile Valley appears to have become definitely established and probably the river in the lower part of its course eventually washed up against and broke down the separating barrier of gravel between the Fayûm and the Nile Valley, so that part of its waters obtained access to the depression, formed a lake on the lowest part, and gradually rose until the whole basin, up to the level of the channel connecting it with the Nile Valley, became filled. Every year thousands of tons of sediment were carried in by the floods and spread out on the floor in the shape of a fan. Probably later, as the Nile level fell, the valley and the depression again became disconnected, until the more modern river, with its gradually rising bed, again attained the requisite altitude. In early historic times the alluvial deposits had probably silted up the lake in its southern central part, and when in the XIIth dynasty the district was first taken in hand by Amenemhat I this part of it must have had the character of a huge marsh, nearly surrounded by open water, rapidly deepening towards the north.

Section VII.—THE NORTHERN DESERT REGION.

The Plateau bounding the Fayûm depression to the north.All along the north-west and north sides the ground rises rapidly from the base of the dip-slope of the plain in a series of escarpments to the summit of the rim of the depression, averaging 340 metres above sea level. Northwards from the summit stretches a rolling pebbly desert, the prevailing character of which is a dark brown, relieved by lighter brown grey and yellow patches, and especially flecked by the light sandy slopes of the undulations. Although the latter seldom rise to any considerable height above the general level of the plain, from the top of the most modest eminence an immense view in every direction can frequently be obtained. The monotony of this desert is only relieved by the occasional belts of sand, which although extremely narrow in width, run for immense distances in almost absolutely straight lines, and in a N.N.W.—S.S.E. direction. Although none of these dunes actually reach the rim of the escarpment we may mention here the beautiful Ghart el Khanashat, an almost straight and apparently unbroken ridge of sand, extremely narrow but of great length. Near its southern extremity the width does not exceed 100 metres; the slopes on both sides are frequently as much as 30°. The commencement of[27] the Ghart el Khanashat was observed on a march from Wadi Natrûn to Mogara; it lay some way to the south of a line joining those two localities but could not be accurately fixed from the line of route. The belt dies out 24 kilometres from the rim of the Fayûm depression, its termination being particularly abrupt, although the height of the ridge diminishes gradually throughout the last kilometre or two. The line of the belt if continued would almost strike the western extremity of the Birket el Qurûn; near its termination the desert is almost flat, the surface being finely gravelly, with numerous groups of silicified trees; tufts of coarse grass grow in some profusion on the sandy ground at the base of the ridge on either side. A fairly well-marked road from the Birket el Qurûn to the Wadi Natrûn passes the end of the ridge and continues northwards at a distance of 200 metres from the east side of the dunes, although apparently gradually diverging eastwards.

Except to the north and north-west of Tamia, where a somewhat extensive and fairly level plain exists, the ground, as already mentioned, rises from the limits of the central plain in a series of escarpments to the summit of the rim of the depression. These cliff lines are broadly speaking three in number and represent the escarpments of the three great rock-stages which build up the northern part of the Fayûm, i.e., the Birket el Qurûn series, the Qasr el Sagha series, and the Fluvio-marine series. It would serve no useful purpose describing these different cliffs in detail; their positions and characters are apparent on the accompanying maps. The intervening plateaux are for the most part dip-slope plains formed of hard bands of rock, which resisting denudation, are left protecting the underlying strata while the softer beds above are cut back at a comparatively rapid rate.

Desert west and south-west of Gar el Gehannem.In December 1902 and March 1903 a traverse was made through the unexplored country west and south-west of Gar el Gehannem, finally connecting up with Wadi Rayan. The highest escarpment, i.e. that of the Fluvio-marine series, dies out about 20 kilometres west of Gar el Gehannem, gradually merging into the undulating gravel-covered plain. The lower escarpments, those of the Qasr el Sagha and Birket el Qurûn series, continue to a considerable distance in a south-westerly direction, although gradually losing the characters of well-marked cliffs. In fact westwards of this the depression gradually shallows, until at a point some 50 kilometres south-west of Gar el Gehannem the floor has attained the level of the ordinary desert plateau, on which the outcrops of the beds of successive rock-stages follow one another in regular order from south to north, but without forming well-marked topographical features, as in the depression.

Hills, capped with dark hard ferruginous silicified grits and puddingstone, were met with in the extreme south-west extension of the depression; these deposits, which will be referred to more fully later, considered in conjunction with the similar beds occurring within the oasis of Baharia, and in the hills of Gar el Hamra, on the plateau immediately to the north-east of that depression, are of considerable interest and importance, especially in connection with the question of the position of the early rivers which in Eocene and later times brought down quantities of trees and animals, the remains of which are so abundant throughout the later Fayûm deposits.

[28]Jebel el Qatrani and escarpments north of the Birket el Qurûn.The boldest part of the region is the area lying between the Birket el Qurûn and the summit of the depression to the north. All three lines of cliff are here high and precipitous, and the uppermost escarpment, well known by the name of Jebel el Qatrani, formed of a highly coloured series of sandstones and clays and capped for a distance of many kilometres by a thick bed of hard black basalt, is of a most striking character. The eastern extremity of Jebel el Qatrani is perhaps the most conspicuous point in the whole region; here the two conical black basalt-capped cliff-outliers, known as Widan el Faras, stand side by side, and from their summits the eye commands the whole region from the pyramid of Lahûn on the one side, across Rayan to the south, up to the extreme limits of the depression to the south-west. The rim of Jebel el Qatrani has a fairly constant level of about 340 metres above the sea. From Widan el Faras the escarpment trends northwards for a few kilometres before again resuming an easterly direction, which is continued till the well-marked bluff of Elwat Hialla is reached. From this summit the pyramids of Dashûr, Saqâra and Giza are visible to the north, as well as Cairo and the Nile Valley southwards, backed by the bluffs on the Eastern desert limestone plateau.

To the south the isolated peaks of Garat el Gindi and Garat el Faras form conspicuous landmarks on the more or less open plain which stretches to Tamia and the limits of the Fayûm cultivated lands. Eastwards the escarpments continue in a broken irregular manner; the upper ones are gradually lost in an undulating plain, while the lower eventually join those forming the northern part of the ridge separating the Fayûm from the Nile Valley.

[6]For fuller details of the cultivated lands, water-supply, etc., of the Fayûm, the reader is referred to the excellent description by Sir Hanbury Brown in his work The Fayum and Lake Moeris, London, 1892.

[7]“The Lake of the Horns,” so called from the narrow horn-like promontories which jut out into the lake on the north side. Views of the lake are shown in Plates I, IV, XVI.

[8]This was the case until a year or two ago. At the present time a limited amount of freshwater finds its way to the area immediately north of the east end of the lake and small plots are cultivated by the arabs.

[9]Herodotus, Book II; Strabo, Book XVII; and Diodorus Siculus, Book I, Chap. LI. (See Brown op. cit. p. 19-22.)

[10]“Hawara, Biahmu and Arsinœ,” 1889.

[11]Brown, op. cit. p. 95. As mentioned above in some areas the cultivated land was formerly even more extensive than at present, notably near the modern villages of Roda, Tamia, etc.

[12]For details of evaporation and level-records of the lake, see Brown, op. cit. pp. 6-9, and P.W.M. annual reports.

[13]See Willcocks’ Egyptian Irrigation, 2nd edition, London, 1899.

[14]See A Preliminary Investigation of the Soil and Water of the Fayûm Province, by A. Lucas, Survey Department, Cairo, 1902.

[15]See Appendix II, A Note by Dr. Schweinfurth on the Salt in the Wadi Rayan, in Willcocks’ Egyptian Irrigation, pp. 460-465.

[16]The word “freshness” is used comparatively, as the amount of salt is sufficient to make the water unpalatable or unfit for drinking, except near the feeder canals. It is, however, quite good enough for most culinary purposes, and camels will usually drink from it, although it is not advisable to water the latter from the lake either before or after a fatiguing desert march, as in such cases the salinity of the water may have bad effects.

[17]“Bull. of the American Geographical Society, 1882, pp. 22 and 24.”

[18]Mémoires sur les travaux publics en Egypte, Paris, 1873, pp. 53, 54.