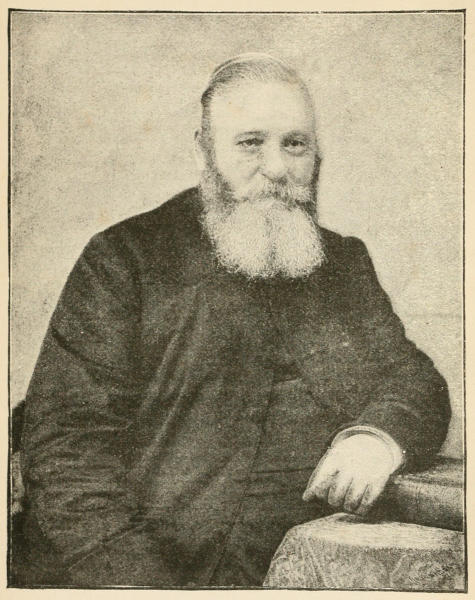

THE RIGHT REV. JOHN HORDEN, BISHOP OF MOOSONEE

THE RIGHT REV. JOHN HORDEN, BISHOP OF MOOSONEE

FORTY-TWO YEARS

AMONGST THE

INDIANS AND ESKIMO

PICTURES FROM THE LIFE OF

THE RIGHT REVEREND JOHN HORDEN

FIRST BISHOP OF MOOSONEE

BY

BEATRICE BATTY

LONDON

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

56 Paternoster Row and 65 St Paul’s Churchyard

1893

PRINTED BY

SPOTTISWOODE AND CO., NEW-STREET SQUARE

LONDON

The contents of the present volume are in a large measure the outcome of a long-continued personal correspondence with the late Bishop of Moosonee.

As Editor of the Coral Magazine I received from him many appeals for aid in the various departments of his work. I asked for graphic descriptions of the surroundings; and I did not ask in vain. Questions concerning the daily life of himself and those about him, the food and habits of the people, modes of travel, dress, climate, products, seasons, and special incidents were duly answered and fully entered into. The bishop had the pen of a ready writer, and all that he wrote was graphic in the extreme. He was, however, modestly unaware of his talent in this respect, until his eyes were opened to the fact by the well-deserved appreciation of the letters and papers[6] which came more frequently and more regularly increasing in interest as time wore on.

The bulk of this book is made up of extracts from this correspondence, with just enough information supplied to give the reader a clear idea of the bishop’s life and work. The journal of his first voyage to the distant sphere of his future labours he sent to me in quite recent years, with the expressed hope that it might be published. The various papers and letters afford not only a vivid picture of life amongst the Indians and Eskimo, but a valuable example of what may be accomplished, even under the most untoward circumstances, by indomitable perseverance, unwavering fortitude, and cheerful self-denial, accompanied always by prayer and a firm reliance upon God. ‘I can do all things through Christ who strengtheneth me’ was the bishop’s watchword. His motto—‘The happiest man is he who is most diligently employed about his Master’s business.’

Should the pictures of life and work offered in the accompanying volume lead others to follow in Bishop Horden’s footsteps, their purpose will have been indeed fulfilled.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Voyage Out | 13 |

| II. | Acquiring the Language | 18 |

| III. | Early Life | 23 |

| IV. | Winter at Moose Fort | 28 |

| V. | A Visit to the Eskimo at Whale River | 42 |

| VI. | School Work | 50 |

| VII. | First Return to England | 56 |

| VIII. | Again at Work | 60 |

| IX. | Days of Labour | 70 |

| X. | The Bishopric of Moosonee | 76 |

| XI. | A Picnic and an Indian Dance | 83 |

| XII. | Organisation and Travel | 92 |

| XIII. | York Factory | 105 |

| XIV. | The Return to Moose | 116 |

| XV. | Trying Times | 132[8] |

| XVI. | Christmas and New Year’s Day at Albany | 150 |

| XVII. | The Packet Month | 160 |

| XVIII. | Churchill and Matawakumma | 172 |

| XIX. | A Day at Bishop’s Court | 183 |

| XX. | Closing Labours | 193 |

| XXI. | Last Days | 219 |

| PAGE | |

| The Right Reverend John Horden, Bishop of Moosonee | Frontispiece |

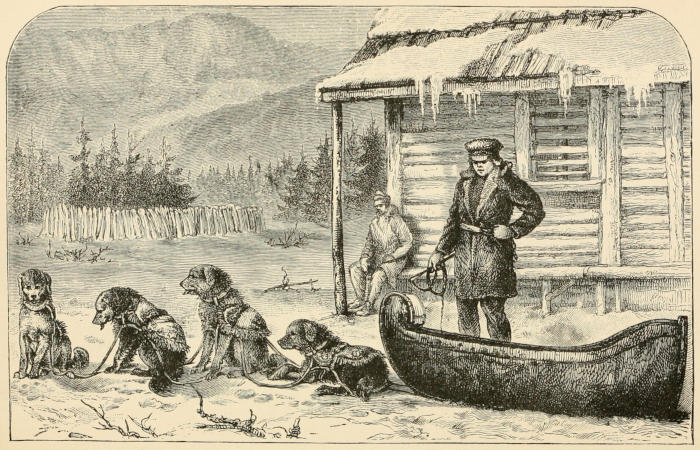

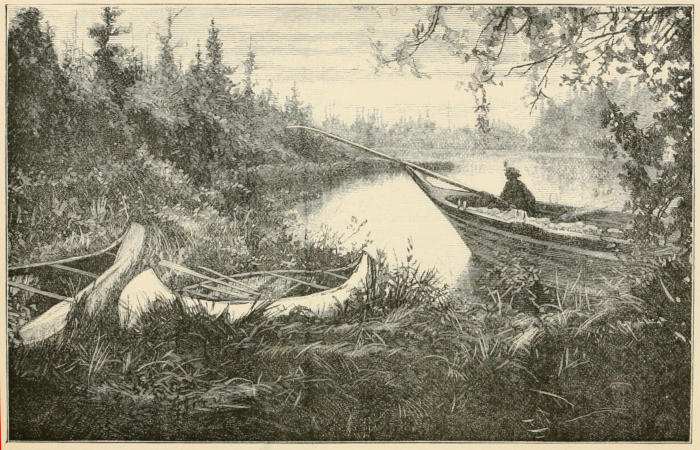

| A Log Hut | 9 |

| Map of Moosonee | 12 |

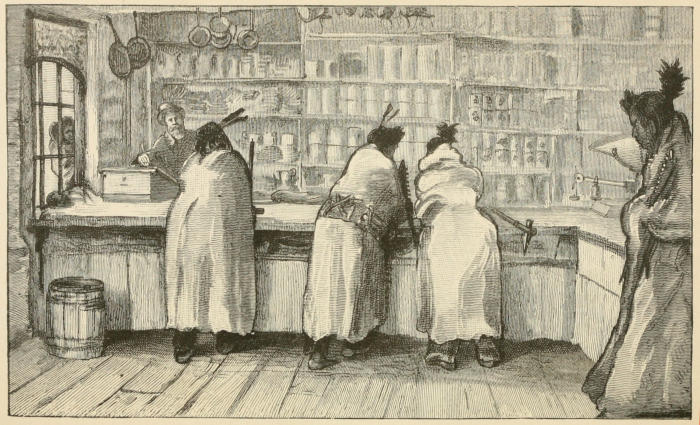

| A Trader’s Store | 36 |

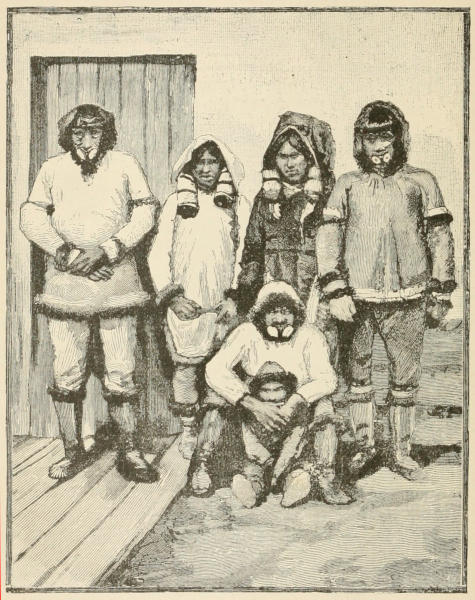

| A Group of Eskimo | 46 |

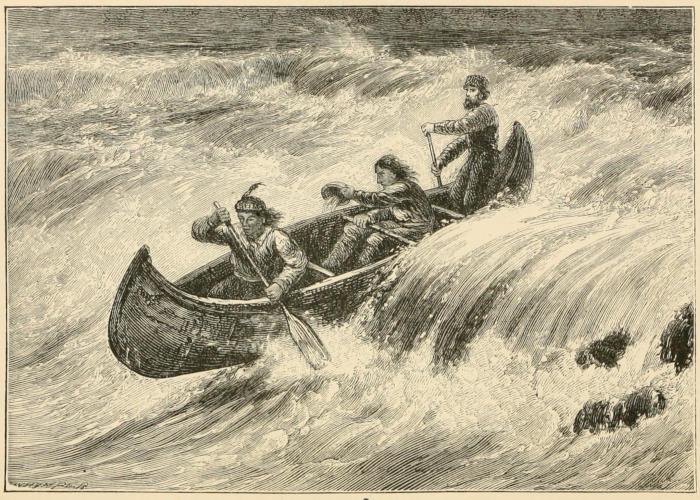

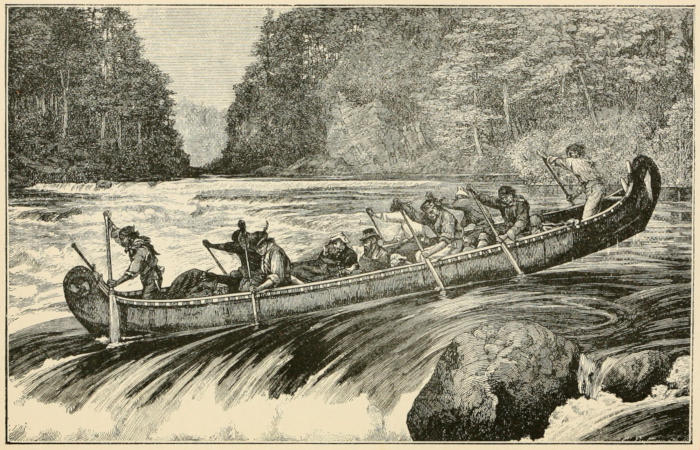

| Shooting a Rapid | 99[10] |

| Canadian Timber | 119 |

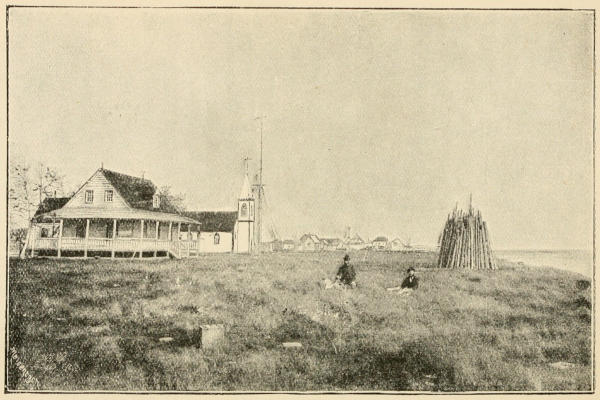

| Moose Factory | 124 |

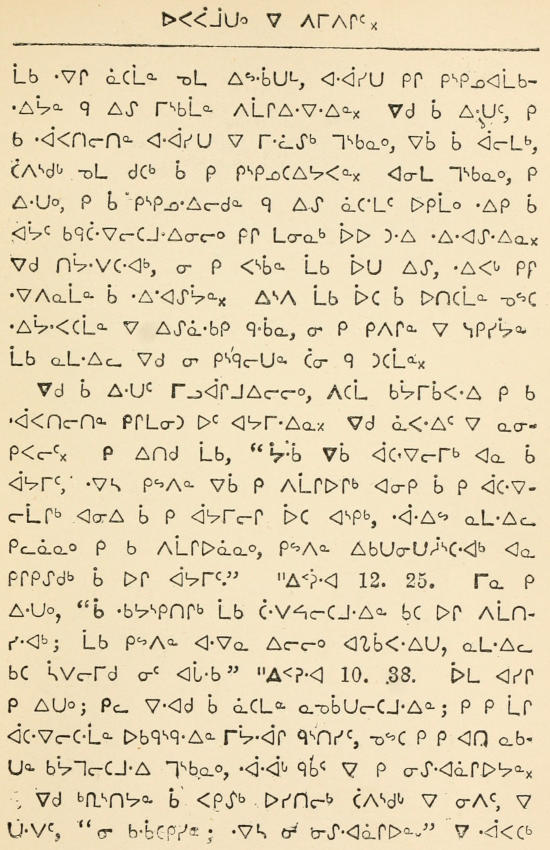

| A Page of the Cree ‘Pilgrim’s Progress’ | 145 |

| A Dog Sledge | 151 |

| Albany, Hudson’s Bay | 156 |

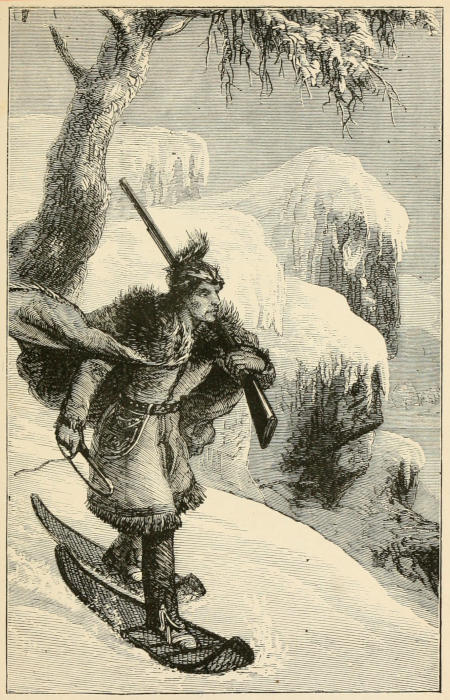

| An Indian travelling on Snow-shoes | 161 |

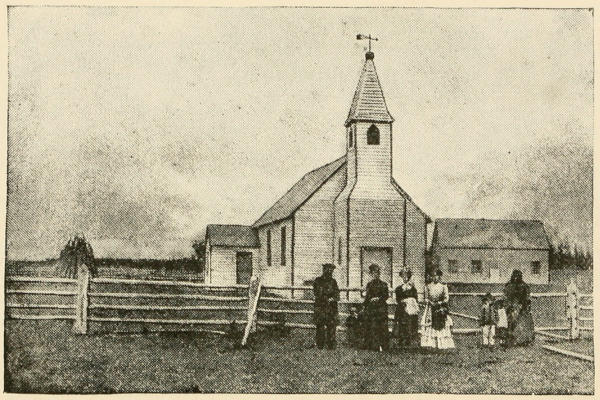

| The Church at Fort George | 169 |

| Churchill in Summer | 173 |

| On the Churchill River | 177 |

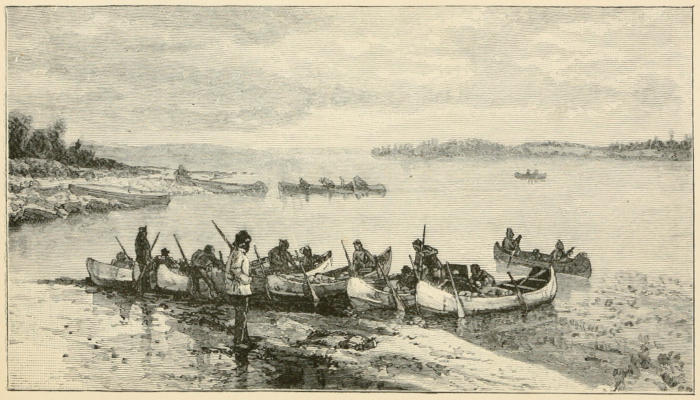

| A Large Canoe shooting a Rapid | 189 |

In the year 1670, a few English gentlemen, ‘the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England trading to Hudson’s Bay,’ obtained a charter from King Charles II. The company consisted of but nine or ten merchants. They made large profits by bartering English goods with the Indians of those wild, and almost unknown, regions for furs of the fox, otter, beaver, bear, lynx, musk, minx, and ermine.

The company established forts, and garrisoned them with Highlanders and Norwegians. The climate was too cold and the food too coarse to attract Englishmen to the service. The forts, or posts, were about a hundred and fifty or two hundred[14] miles apart, and to them the Indians resorted in the spring of the year with the furs obtained by hunting, snaring, and other modes of capture. In return for these they obtained guns, powder and shot, traps, kettles, axes, cloth, and blankets. The standard of value for everything was a beaver skin. Two white foxes were worth one beaver skin, two silver foxes were worth eight beaver skins, one pocket-handkerchief was worth one beaver skin, one yard of blue cloth was worth one-and-a-half beaver skins, a frying-pan was worth two beaver skins. As time went on, and the value of furs in the market rose or fell, the prices of certain things altered. But this is a sample of what they were when the hero of our tale first went out to Hudson’s Bay in 1851.

Let us accompany the young missionary on his voyage to Moose Fort, the chief of the company’s trading posts. ‘We, that is, my dear wife and myself,’ he writes, ‘went on board ship at Gravesend on June 6, 1851. Our ship was strongly built, double throughout; it was armed with thick blocks of timber, called ice chocks, at the bows, to enable it to do battle with the ice it would have to encounter. At Stromness we remained a fortnight, taking in a portion of our cargo and a number of men who were going to Hudson’s Bay in the service of the company. It was a solitary voyage. All the way we saw but one vessel. On a Saturday afternoon we entered the Straits.

‘The weather had been very foggy; but the fog rose, the sun shone out, and a most beautiful spectacle[15] presented itself. The water was as smooth as a fish-pond, and in it were lying blocks of ice of all sizes and shapes, some of them resembling churches, others castles, and others hulls of ships, while at a considerable distance, on either side, rose the wild and dreary land—a land of desolation and death, without a tree or a blade of grass, but high and mountainous, with masses of snow lying in all the hollows. The captain and mates became very anxious. The dangers of the voyage had commenced. An ice-stage, raised eight or nine feet above the deck, was erected, and on this continually walked up and down one or two of the ship’s officers. A man, too, was constantly at the bow on the look out, and yet the blows we received were very heavy, setting the bells a-ringing, and causing a sensation of fear.

‘When we had got about half-way through the Straits, we saw some of the inhabitants of this dreary land. “The Eskimo are coming,” said a sailor.

‘By-and-by, I heard the word Chimo frequently repeated, which means “Welcome,” and presently we saw a number of beautiful little canoes coming towards us, each containing a man. These were soon followed by a large boat containing several women and children. They all came alongside, bringing with them seal-skins, blubber, fox-skins, whalebone, and ivory. These they freely parted with in exchange for pieces of iron, needles, nails, saws, &c., they setting a very great value on anything made of iron. Now these people, who were very, very dirty, were not dressed like English people, but both men and women wore coats[16] made of seal-skins, breeches of dog-skins, and boots of well-dressed seal-skins, the only difference between a man’s and a woman’s dress being that the woman had a long tail to her coat, reaching almost to the ground, and an immense hood, in which she carried her little naked baby, which was perched on her shoulders.

‘Again hoisting our sails, in two or three days we cleared the Straits and entered Hudson’s Bay. Danger was not over. Our difficulties had scarcely commenced. Ahead, stretching as far as the eye could reach, is ice—ice; now we are in it. More and more difficult becomes the navigation. We are at a standstill. We go to the mast-head—ice! rugged ice in every direction! One day passes by—two, three, four. The cold is intense. Our hopes sink lower and lower; a week passes. The sailors are allowed to get out and have a game at football; the days pass on; for nearly three weeks we are imprisoned. Then there is a movement in the ice. It is opening. The ship is clear! Every man is on deck. Up with the sails in all speed! Crack, crack, go the blows from the ice through which we are passing; but we shall now soon be free, and in the open sea. Ah! no prisoner ever left his prison with greater joy than we left ours.

‘A few days afterwards, as evening was closing in, there was a great commotion on board: heavy chains were got on deck; we were nearing the place of our destination; in the midnight darkness the roar of our guns announced the joyful intelligence that we[17] were anchored at the Second Buoy, only twenty-five miles from Moose Fort.’

Looking at the map of North America, a little inland from the coast of Labrador, you will find Hudson’s Bay, and in the south-west corner, at the mouth of the Moose River, Moose Fort. Here is the residence of the deputy governor and his subordinate officers; a number of people are anxiously looking out; they are expecting the one ship that comes to them in the course of the year. A small vessel lying a little way out to sea has raised the long-looked-for signal, and rejoicing is the order of the day.

Our travellers were delighted with the appearance of Moose Fort and its immediate surroundings. The little church, the line of neat cottages with their gardens in front, and the new factory buildings, lying irregularly along the banks of the river, gave the place almost the air of an English village. Towering picturesquely above all, was the old fort, strongly built and loopholed, now serving the purpose of a salesroom, but once needed as a place of defence from attacks of the Indians. Poplars, pines, and juniper formed a green background, and the place bore a smiling and pleasant aspect, altogether surprising to those who had expected to arrive on a barren and desolate shore.

Mr. Horden was received with unmistakable joy by the people, who had long been left without a teacher, his predecessor in the office having quitted Moose Fort the year before. He was at once at home amongst the Indians, and immediately set about learning their difficult language.

Greek and Latin he declared to be tame affairs ‘in comparison with Sakehao and Ketemakalemāo, with their animate and inanimate forms, their direct[19] and inverse, their reciprocal and reflective, their absolute and relative, their want of an infinitive mood, and their two first persons plural. This I found very troublesome for a long time; to use kelananow for we, when I meant I and you; and nelanan, when I wished to express I and he. If merely the extra pronoun had required to be learnt, I should not have minded, but I did mind very much when I found in the verb the pronoun inseparably mixed up with the verb, and that in portions of it the whole of the personal pronouns were expressed by different inflections of the verb. But I had the very strongest of motives to urge me forward: the desire to speak to the Indian in his own language the life-giving words of the Gospel.

‘I had been at my new home but a few days before I set to work in earnest. The plan I adopted was this: every week, with the assistance of an interpreter, I translated a small portion of the service of the English Church. This I read over and over again, until I had nearly committed it to memory, and was able to read it on Sunday. The Lord’s Prayer and a few hymns I found already translated, and I soon added a few hymns more. Chapters of the Bible and sermons were rendered by the interpreter sentence by sentence. Rather tedious, but we improved fast, and I shall not soon forget the expression of surprise and joy on the countenances of my congregation, when, after a few months, I made my first address to them without an interpreter—but I am anticipating.

‘My plan was threefold. I provided myself with two books and a living instructor; the latter a young Indian with a smattering of English. The first of the two books was a small one to carry in my pocket; in it I wrote a few questions with the aid of the interpreter. Having learnt them, I went into an Indian tent, sat down among its inmates, drew out book and pencil, and put one of my questions. One of those present would at once give me an answer, entering generally into a long explanation, of which I did not understand a word. However, they, knowing my aim, talked on, and I listened, wondering what it was all about. Getting gradually bewildered, I returned home. I repeated the process again and again, and after a few days light began to shine out of darkness, the jumble divided itself into words, the book and pencil no longer lay idle, every word that I could separate from the others was at once jotted down, all were copied out, translated as far as possible, and committed to memory; and presently I got not only to catch up the words, but likewise to understand a good deal of what was said.

‘The second book was a much larger one, and ruled. Having this and pen and ink by my side, I would call an Indian, and he would take his seat opposite; I then made him understand that I wished him to talk about something, and that I wished to write down what he said. He would begin to speak, but too fast; I shook my head, and said, Pākack, pākack—“slowly, slowly,” and at a more reasonable rate he would recommence. As he spoke,[21] so I wrote, writing on every other line. We sat thus until I could bear no more. Then, with the interpreter’s assistance, I wrote the translation of each word directly under it, thus making an interline. The work was a little trying, but by it I gained words, I gained words in combination, I gained the inflections of words, I gained the idiom of the language, I gained a knowledge of the mind of the Indian, the channel in which his ideas ran, I gained a knowledge of his mode of life, the trials and privations to which he was subjected.

‘Now as to the Indian lad. I began by drilling him in the powers of an English verb, and after a few days we said a lesson to each other, he saying—First person singular, I love; second person singular, thou lovest, &c. Then I going on with mine, thus:

| Ne sakehou | I love him. |

| Ke sakehou | Thou lovest him. |

| Sakehao | He loves him. |

| Ne sakehanam | We love him. |

| Ke sakehanou | We love him. |

| Ke sakehawou | You love him. |

| Sakehawuh | They love him. |

Then the inverse form:

| Ne sakehik | Me loves he. |

| Ke sakehik | Thee loves he. |

| Sakehiko | He is loved by him. |

| Ne sakihikonau | Us loves he. |

| Ke sakehikonau | Us loves he. |

| Ke sakehikowou | You loves he. |

| Sakehikowuk | They are loved by him. |

And so on and on. The subjunctive mood, with its iks and uks and aks and chucks, was terribly formidable, still the march was onward, every week the drudgery became less and the pleasure greater, and every week I was able to enter more and more into conversation with those who formed my spiritual charge.

‘In my talk I made mistakes enough. Once I had a class of young men sitting around me, and was telling them of the creation of Adam and Eve. All went well until I came to speak of Eve’s creation; I got as far as “God created Eve out of one of Adam’s ——,” when something more than a smile broke forth from my companions. Instead of saying, “out of one of Adam’s ribs,” I had said, “out of one of Adam’s pipes.” Ospikakun is “his rib,” and ospwakun, “his pipe.”

‘After eight months I never used an interpreter in my public ministrations, and I had been in the country but a few days more than a twelvemonth, when, standing by the side of good Bishop Anderson, I interpreted his sermon to a congregation of Albany Indians. I say this with deep thankfulness to God for assisting me in my formidable undertaking.’

Mr. Horden had not only a wonderful power of acquiring languages, but a wonderful power of adapting himself to all things, people, and circumstances. This stood him in good stead throughout his career. Born in Exeter, January 20, 1828, in humble circumstances, simply educated, apprenticed to a trade in early boyhood, he lived to attain a high position. All difficulties were overcome by his dauntless energy of purpose and unwavering perseverance.

He wished to study, but his father put him to a smithy. He desired to become a missionary, but his relatives discouraged the idea. He did not rebel, he did not kick against authority, but he neglected no opportunity to further his purpose. He read and thought, he attended evening Bible readings, he taught in the Sunday school, and when his indentures were out he left the anvil for the desk. He obtained the post of usher in a boys’ school. And now being independent, he offered himself to the Church Missionary Society, with a view to going to India as a lay agent, and he was accepted with the understanding[24] that he would await a suitable opening, which might perhaps not occur for two or three years.

He was willing to wait, but his patience was not to be tried. The society learnt that the Wesleyans had withdrawn from Hudson’s Bay, and that there was great need of a teacher at Moose Fort. Here was an opening for a young man such as John Horden appeared to be. Hastily he was telegraphed for—Hudson’s Bay was not India! But he was willing to go. It were better he should take a wife with him. The lady was ready, like-minded with himself. They must start in three weeks. They agreed to do it. He went home, got married, and returned to London. The needful outfit was hastily prepared, and they started, as we have seen. Such in short is the story of our hero’s earlier life.

Large and varied were to be his experiences in his later years. The society at home hearing of his success with the Indians, his great progress in learning the language, and his ready adaptability to all the requirements of the post, had determined to send him to the Bishop of Rupert’s Land for ordination. ‘But,’ said the bishop, ‘this plan was formed in ignorance of the distance and difficulties of travelling in this part of the country, and I did not wish to expose Mr. Horden with wife and baby to it.’ Bishop Anderson chose rather to traverse his huge diocese and ordain the young missionary at Moose.

On the morning of June 28, in the year 1852, the start was made from St. Andrews, Red River, in a[25] canoe decorated by one of the bishop’s scholars with a mitre and the Union flag at the stern, and at the bow a rose and duck. For the latter ‘I might have substituted the dove with the olive branch, had I known of it in time,’ says the bishop, ‘but it was done to surprise me, and the more familiar object was naturally enough selected.’ The provisions consisted largely of flour and pemmican, the clothing, of the bishop’s robes and a few necessaries, the bedding, of a pillow with a buffalo robe and blankets. The journey lasted six weeks. Throughout it the bishop confirmed, married, and baptized as he passed from post to post, and on arriving at Moose Fort the work was repeated. He found the Indians full of love and regard for their teacher. ‘He has their hearts and affections,’ he wrote, ‘and their eyes turn to him at once. This is his best testimonial for holy orders.’

Careful examination of the candidate still further convinced the bishop of his suitability, and when the annual ship arrived bringing an English clergyman, the Rev. E. A. Watkins, destined for Fort George, he no longer delayed, but ordained Mr. Horden both deacon and priest, Mr. Watkins presenting. The bishop and Mr. Watkins had then to hasten on their several ways, lest early winter might overtake them ere they reached their destinations. And so the ardent, earnest young catechist was left at Moose, pastor as well as teacher of his flock, known to and esteemed by every man, woman and child of the Indian families who resorted thither during the summer season, and supremely happy in his work and position.

The home in which he and his wife dwelt was of the simplest, its walls were of plain pine wood; but within it was enlivened by the baby prattle of their first-born child, baptized by the bishop, Elizabeth Anderson. Without, it was surrounded by a garden, in which some hardy flowers grew side by side with potatoes, turnips, peas, and barley. Moose is not by any means bare of wild flowers, and in mosses it is very rich, whilst goodly clumps of trees waved their branches in the breeze on an island only five minutes’ walk from the house. During the winter the missionary and his family, together with the three or four gentlemen of the Hudson’s Bay Company, with their servants, and a few sick and aged Indians and children, were the sole inhabitants of the settlement. Then Mr. Horden gave himself up to his little school, to his translation work, and to such building operations as in course of time became necessary—a school-house, a church, a new dwelling-house. After dinner he was occupied with hammer, chisel, saw and plane until dark. In the evening he gave instruction to a few young men.

One such, whom he employed for a time as a school assistant in later years, he had the pleasure of sending in due course for ordination by the Bishop of Rupert’s Land, who appointed him to the charge of Albany station, one hundred miles north of Moose, an important outpost, at which eighty families of Indians congregated during the summer. Hannah Bay, another post, fifty miles east of Moose, was resorted to by fifty families; Rupert’s House, one[27] hundred miles east, was frequented by sixty families; and Kevoogoonisse, 430 miles south, by thirty families. All these places were to be visited by Mr. Horden, as well as Martin’s Falls, three hundred miles from Albany, and Osnaburg, two hundred miles further on; also Flying Post, one hundred from Kevoogoonisse, and New Brunswick, one hundred from Flying Post.

This was sufficient to appal the mind and daunt the courage of one still young and inexperienced. It did not daunt John Horden. He longed only to teach all who were thus placed under his ministerial charge. The journeys must be made at particular seasons, as throughout the greater part of the year no Indians were at the trading-posts.

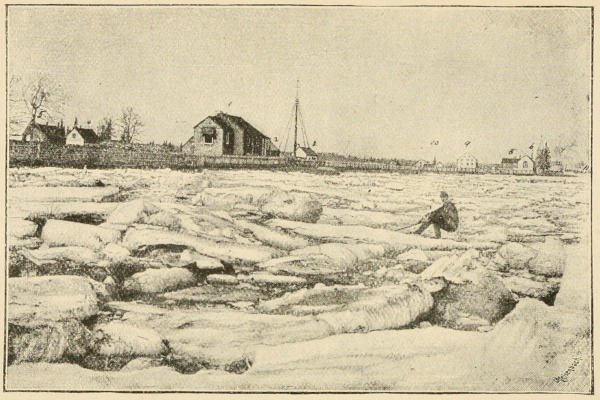

The four seasons are called in the Indian tongue, Sekwun, Nepin, Tukwaukin, and Pepooa. Spring begins about the middle or end of May, when the ice in the river breaks up. Vegetation proceeds rapidly. In a few days the bushes look green, and within a fortnight the grass and trees appear in summer garb. Sometimes the ‘breaking-up’ is attended with danger, often with inconvenience.

In the spring of 1860 the little settlement was visited with a disastrous flood. The ground all around is low, not a hill within seventy miles. Mr. Horden was occupied in building his new church—the frame already rested on the foundations. One Sunday morning it floated off and took an excursion of nearly a quarter of a mile, and with the aid of ropes, poles, and other implements it had to be dragged back to its former position and strongly secured. ‘The ice,’ said Mr. Horden, ‘made much more havoc than it did in ’57. A few days after the water had subsided I found my garden thickly planted with ice blocks of a considerable size; but our gardening operations were not impeded, we were able[29] to raise a large quantity of potatoes of very good quality. The effects of a flood are not always evident at once; it is after the lapse of months that they become apparent, when the poor Indian on arriving at his winter hunting-grounds finds that the water has been there, and destroyed nearly the whole of the rabbits. He is reduced to great straits, and the energies of the whole family are required to keep them from starvation.’

Rabbits are the staple food of the Indians in the season. The skins, being of little value for barter, are used by them as blankets, the women sewing them very neatly together.

In 1861 Mr. Horden writes: ‘In May we were again threatened with a flood. On returning from church one Sunday evening the river presented an awful appearance. The strength of the current had broken up the ice, and formed it into a conical shape, which rose as high as the tops of the trees on the high bank of the river. We abandoned our house, having first taken every precaution to guard against the fury of the waters, but, although the threat was so formidable, we experienced no flood, and after spending a few pleasant days at the establishment of the Hudson’s Bay Company we returned, and at once began our gardening. The children look upon a flood as a rare treat. To them it is something of a pleasant, exciting nature, after the dull monotony of a seven or eight months’ winter. It drives us from our house, but we take shelter in one equally good, where we ourselves enjoy pleasant company, and where the[30] children have a large number of playmates. What we look upon as our greatest trial are the privations and sufferings to which the Indians are subjected.’

Nepin is very changeable, sometimes excessively warm, with plenty of mosquitoes and sand-flies, which are very troublesome; sometimes quite cold, and the transition is very rapid. It may be hot in the morning, and in the evening so cold that an overcoat may be worn with comfort.

‘This is the busy season,’ writes Mr. Horden, ‘when I take my journeys. Brigades of canoes from the various posts arrive, bringing the furs collected during the preceding winter; in fact, every person appears to have plenty to do.’ Just as summer is ending, the ship arrives, and it is very anxiously looked for, for on it almost everything depends—flour, tea, clothing, books, everything.

‘Tukwaukin is generally very boisterous, with occasional hail and snow storms. Then the Indians hunt geese, which are salted and put into barrels for our use, although they are not quite so good as a corned round of beef. Before the arrival of Pepooa, all of the Indians are gone off to their winter grounds, from which most of them do not return until the arrival of spring.’

Each point of Mr. Horden’s vast parish had to be reached by an arduous journey. Arduous is indeed but a mild expression for the troubles, trials, privations, and tremendous difficulties attendant on travel through the immense, trackless wastes lying between many of the posts—wastes intersected with[31] rivers and rapids, varied only by tracts of pathless forest, swept by severe storms. ‘Last autumn,’ he writes, ‘I took a journey to Kevoogoonisse; it is 430 miles distant, and during the whole way I saw no tent or house, not even a human being, until I arrived within a short distance of the post. I appeared to be passing through a forgotten land; I saw trees by tens of thousands, living, decaying, and dead; I saw majestic waterfalls, and passed through fearful rapids; I walked over long and difficult places, and day after day struck my little tent, and felt grieved at seeing no new faces, none to whom I might impart some spiritual blessing. In the whole space of country over which I travelled, perhaps a dozen Indian families hunt during the winter. Sometimes even this tract is insufficient to supply their wants; animals become scarce, the lands are burnt by the forest fires, and they are reduced to the greatest distress. I have seen terrible cases of this kind. I have seen a man with an emaciated countenance, who in one winter lost six children, all he had; and, horrible to relate, nearly every one of them was killed for the purpose of satisfying the cravings of hunger. At the post to which he was attached, Kevoogoonisse, out of about 120 Indians, twenty died through starvation in one winter.’

The country may be said to be one vast forest, with very extensive plains, watered by large rivers and numerous lakes, inhabited by a few roving Indians, who are engaged in hunting wild animals to procure furs for the use of civilized man.

Sometimes sad things took place during the absence of the missionary on his journeyings to visit outlying stations. During the short summer of 1858, he set out with his wife and their little children to visit Whale River, in the country of the Eskimo. It was not his first journey to that post. ‘You will have need of all your courage,’ said he to his wife. Tempestuous seas, shelterless nights, and stormy days were vivid to his own memory, but wife and children were glad to see anything new, after the monotonous days and nights of the long Moose winter.

The family had not long been gone, when whooping-cough broke out at Moose. Young, old, and middle-aged were attacked alike, and numbers died. So terrible was the sickness that at one time there was but one man able to work, and his work was to make two coffins. The missionary returned to a sorrowing people. Out of five European families four had lost each a child, and ‘the sight of the grave-yard and the mothers weeping there is one I never shall forget. In ordinary years the average mortality was two. This year it was thirty-two.’ Amongst the children taken was dear little Susan, the orphan child of a heathen Indian, whom they had cared for from infancy, and whose little fingers had just before her illness traced upon a sampler the text: ‘Remember now thy Creator in the days of thy youth, while the evil days’——Here the words had ceased—she was taken from all evil, and the evil days would not draw nigh her, the needle remained in the sampler at that spot. Amongst the aged taken were blind Koote, old blind Adam,[33] and old blind Hannah, all of whom are specially mentioned in Mr. Horden’s account of the previous Christmas Day services.

‘Yesterday,’ he writes, speaking of Christmas 1857, ‘was a deeply interesting one to me. As usual, I met the Indians at seven, the English-speaking congregation at eleven, and Indians again at three. Among the communicants present were no less than three blind persons. Old Adam, over whose head have, I should think, passed a hundred winters. Old Koote, always at church, led with a string by a little boy, and poor old lame Hannah, whose seat is seldom empty, be the weather what it may. The day previous to our communion we had a meeting of the communicants. Old blind Koote said, “I thank God for having preserved me to this day. God is good! I pray to Him every night and morning. That does good to my soul. I think a great deal about heaven, I ask Jesus to wash away all my sins, and to take me there.”’

Any of the Indians who can come in to celebrate the Christmas and New Year’s festivals eagerly seize the opportunity. But this is not possible for the greater number, whose hunting-grounds lie at considerable distances from the fort. In their far-away tents they have no means of Christian communion or instruction, except by intercourse with one another, and by the study of the portions of Scripture, prayers, and hymns which they gladly and thankfully carry away with them to their lonely homes in the wilderness.

The society had sent out a printing-press to Moose Fort, to facilitate the supply of books to the Indians. Mr. Horden had hoped to receive by the ship copies of his translations ready printed, instead of which, to his dismay, blank sheets arrived with the press. He was no printer, although his father had been, and now his energy, courage, and power to overcome difficulties pre-eminently showed themselves. He shut himself up in his room for several days, resolved to master the putting together of the press; a very complicated business. But he accomplished it, and great was his joy and triumph when he found that the machinery would work. From this press issued, in one winter, no less than sixteen hundred books in three Indian dialects.

The winter over and gone, the snow nearly disappeared, day after day the geese and wavies are seen flying overhead. The mighty river, which has been for many months locked up, with a giant’s strength has burst its bonds asunder, and rushes impetuously towards the sea; a few birds appear in the trees, the frogs have commenced their croaking, fish find their way to the well-laid nets; and the busy mosquito has begun its unwelcome buzz. The Indians collect their furs, tie them in bundles, and place them in the canoes, and with their dogs and household stuff they make their way down stream to the trader’s residence. They run a few rapids, carry their canoe and baggage over many portages, sail the frail bark over one or two lakes, and are at the end of their journey. Down come the[35] trader’s servants to help to carry the packs to the store.

A TRADER’S STORE

Let us look around. The store contains everything that an Indian needs, whether for business or comfort. Here a rack full of guns, there a pile of thick blankets, a bale of blanket coats, and an almost unlimited supply of blue and red cloth; axes and knives, matches and kettles, beads and braid, deer-skin and moose-skin, powder and shot, twine for nets and snares, tea and sugar, flour and oatmeal, pork and pease; and some good books too, which tell the Indian of God and heaven, and which he can read.

The trader approaches, his face beaming with delight as he eyes the packs, for they are large and valuable. He soon begins work. The first bale contains nothing but beaver skins. Eighty-five examined are said to be worth a hundred and twenty beaver according to the standard value. The next contains forty marten, ten otter, a hundred and fifty rat. These are adjudged worth a hundred beaver; the third bale is composed of five hundred rabbit skins, worth twenty-five beaver. Consider a beaver equal to two shillings and sixpence, and you will see the value of the hunt in sterling money. We have now—bale one value one hundred and twenty beaver; bale two value one hundred beaver; and bale three value twenty-five beaver; altogether two-hundred-and-forty-five beaver. Last summer yonder Indian took out a debt in goods of one hundred and fifty beaver, this he pays, and then he[38] has ninety-five beaver with which to trade. Ninety-five quills are given to him, and his trading begins. The trader, like an English shopman, stands behind a counter, and the Indian outside. Native-like, he consults long before the purchase of each article. Having decided, he calls out, ‘A gun;’ a gun is delivered, and he pays over ten of his quills; then three yards of cloth, for which he pays two quills; two books, and for them he pays one quill; and so on he goes, the heap of goods increasing and the supply of quills decreasing gradually. As he approaches the end, the consultation becomes very anxious; he is making quite sure that he is laying out his money to the best advantage. But the end comes at last, and, satisfied with his bargains, he gathers all up into one of the purchased blankets, and retires to his tent, where he examines and admires, and admires again, article after article.

Shall we take a peep into an Indian’s tent when encamped in the forest on a trapping expedition? A fire burns in the centre, but through the large opening overhead we see the snow lying thick on the branches of the trees. The day has just broken, but the Christian Indian has already engaged in worship and taken his morning meal. Then on with his snow-shoes, for there is no moving without them. The blanket which forms the tent door is raised, and he steps outside. How cold! and how drear the scene! how still and death-like! no birds, no sound, save the wind whistling through the forest. Now he is at a marten trap, a very simple contrivance, composed[39] of a framework of sticks, in the middle of which a bait is placed, which being meddled with, causes the descent of a log, which crushes the intruder. Here is a beautiful dark marten, quite a prize. He takes it out and fastens it to a sledge, re-baits the trap, and on he goes to another. Ah! he sees tracks, but the marten has not entered the trap; on to another. What is this? He looks dismayed; a wolverine has been here, and has robbed the trap. He resets it and goes on to the next; the wolverine has been there too; to another and another, with the same result. He is disheartened, but it cannot be helped. So he trudges on over a round of thirty traps, taking altogether six fine martens; not a bad day’s hunt, all things considered. Evening is drawing on. He returns to the tent, and there awaits him a glorious repast, perhaps of beaver meat. He feels quite refreshed, and recounts all the vicissitudes of the day, the gains and disappointments.

On the morrow he takes the martens and skins them; and what is he to do with the bodies? Our Indian friends are not fastidious. He eats them. The skins he turns inside out, and stitches them up. In the spring he brings them to the fur-trading post, and there exchanges them, as we have seen, for all the requisites of Indian life. An Indian cannot afford to cast away anything; all he kills is to him ‘beef,’ sometimes good, sometimes not a little bad. ‘In my own experience,’ Mr. Horden says, ‘I have eaten white bear, black bear, wild cat, while for a[40] week or ten days together I have had nothing but beaver, and glad indeed I have been to get it.’

When the Indians have come into the post the work of instruction at once commences. Amid school-work, services, visiting and talking with individuals, the missionary found his time fully occupied. Little leisure remained for his dearly-loved translation work—yet this progressed. In 1859 Mr. Horden had already the prayer and hymn book and the four Gospels printed in the syllabic character. The prayer and hymn book were printed in England. The Gospels he had himself printed at Moose. ‘The performance of this labour,’ he writes, ‘was almost too much for me, as, since last winter, although not incapacitated for work, I have felt that even a very strong constitution has limits, which it may not pass with impunity; I have occasionally suffered from weakness of the chest. I need not say with what delight the Indians received the books prepared for them. I did not think it right to provide them all gratis, I therefore charged two shillings each, a little less than one beaver skin, and with the money thus raised I am able to purchase a year’s consumption of paper. Our services are now conducted in a manner very similar to what they are at home. Our meetings for prayer are extremely refreshing, and my spirit is often revived by joining with my brethren around the throne of grace.’

It must be remembered that Mr. Horden had not only the Indians under his ministry, but the Europeans of the Hudson’s Bay Company; thus he had English as well as Indian services to hold, and as there were[41] some Norwegians amongst the company’s servants who did not readily follow either the English or the Indian, he set himself to learn for their sake sufficient Norwegian to read the service and to preach to them in their own tongue.

To these languages he added Eskimo and Ojibbeway—the latter being the speech of the people of the Kevoogoonisse district, the former that of the natives of Whale River.

How could all this be crowded into the busy day of this father of his flock? How but by rising in the small hours of the morning, when by the light of a lamp in his little study he read, and wrote, and translated, and in addition to all else taught himself Hebrew.

In February 1861, Mr. Horden writes, ‘My hands are quite full; I find it impossible to do all that I should wish to do. On Sundays I hold three full services, and attend school twice, and every morning except Saturday I conduct school. On Tuesday afternoon and Wednesday evening I hold a service. These matters, with my house and sick visiting, leave me very little leisure. But as myself and my family enjoy good health, I can say that happiness is to be found as well among the primeval forests of Moosonee as in the more sunny land of our birth.’

For his Eskimo children the bishop always had a very special affection. Very early in his missionary career he managed, as we have seen, to pay them a visit. He then could not converse with them, nor could he do so without the aid of an interpreter when he paid a summer visit to Whale River about the year 1862. We give his own graphic account of this.

‘Let our thoughts for a while be transferred to a land more bleak and desolate than Moose, to the land where snow never entirely disappears, to the land of barren rock and howling storm, to the country of the[43] white bear and the hardy Eskimo, where I spent some time last summer. I remained with the Eskimo only eight days, yet those eight days were indeed blessed ones, and will not soon be forgotten by me, for they were amongst the most successful missionary days I have had since I have been in the country.

‘The Eskimo appeared to me to be kind, cheerful, docile, persevering, and honest. Nothing could exceed the desire they professed for instruction, nothing the exertions they made to learn to read, nothing the attention with which they listened to the Word of God. I was most fortunate (but should I not use another word?) in obtaining the services of a young Eskimo as my interpreter, who had received instruction from missionaries (Moravians) while living on the coast of Labrador. He spoke English but imperfectly; but knew some hymns and texts exceedingly well, and showed himself most willing to assist me to the fullest extent of his power. I could not have done half the work I did, had I not had him as my assistant. Accompany me for a day, commencing with the early morning.

‘Soon after six we had a service with the Eskimo; about twenty-five were present. Some of the men were dressed very much like working men in England. They purchase their clothing from the store of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Others were dressed in the comfortable native style, composed of a loose seal-skin jacket coming to the waist, seal-skin breeches, and seal-skin boots. One of the women had on an English gown, of which she seemed not a[44] little proud; the others were attired in a dress somewhat similar to the men, with the addition of an immense hood to their jackets, in which they deposit their little babies.

‘The service was commenced by singing a hymn; reading followed, then prayer, the Lord’s Prayer being repeated aloud by all; singing again; then a long lesson on the “Syllabariam,” i.e. the system of reading by syllables, without the labour of spelling. They were then instructed in Watt’s First Catechism, and another hymn completed the service. After having taken my breakfast, I assembled the Indians, who were nearly twice the number of the Eskimo, but not half as painstaking. My service with them was somewhat less simple than that with the Eskimo, as they had received more instruction, and a few could use their prayer books intelligently; but I noticed an apathy among them which rather disheartened me.

‘I then took a lesson from my Eskimo interpreter, writing questions and obtaining his assistance in translating a portion of the baptismal and marriage services; I then went to the Eskimo tents until dinner-time. They are made of seal-skins in the shape of a common marquee. Some of them are spacious and not very dirty. In the centre is a fire, over which is suspended a large kettle full of cray-fish. An old woman was sewing very industriously at a pair of seal-skin short boots, which she presented to me. Her husband was equally industrious, making models of Eskimo implements. I instantly transferred[45] to paper the few words of conversation they had with me. My next visit was to a tent where younger people were assembled. I asked a few questions, which they readily answered. I was pleased at this, as showing that they could understand me. I then dined, and took a short stroll along the river towards the sea, to see what prospect there was for the whale fishermen. The fishers were there, waiting patiently, but with the look of disappointment on their countenances. They could see hundreds of whales outside the bar of the river, but while they remained there not one could be caught, and there seemed no chance of any coming inside the bar. Leaving them, I went to hold a second service with my Eskimo, then another with my Indians. It was then tea-time. I spent an hour with my Eskimo interpreter, after which I held an English service with the master and mistress, the only English-speaking woman for hundreds of miles, and the European servants of the company. Half an hour’s social chat at length closed the day, and with feelings of thankfulness at having been placed as a labourer in the vineyard of the Lord, I retired to rest.

A GROUP OF ESKIMO

‘I was so deeply impressed with the conduct of the Eskimo, their anxiety to learn, and their love for the truths of Christianity, that I could not forbid water that some of them should be baptized. Three of them could read well; these received the rite of baptism at an evening service, all the Europeans being present, for all appeared to take a deep interest in the proceedings. All three were young, neat, tidy,[48] and dressed in European costume. They answered my inquiries very intelligently, receiving severally the names of John Horden, Thomas Henry, and Elizabeth Oke. John and Elizabeth were afterwards married. Malikto, the father of the bridegroom, stood up at the conclusion of the service, and said that he hoped they would not forget the instruction they had received, after I left them. It was a delightful but solemn service.’

The Eskimo formed a large part of Mr. Horden’s charge, and he was much attracted by their gentle contentment amidst their dreary surroundings, and by their teachableness. ‘What should we have been, had we, like them,’ he said, ‘had no Bible to direct us to God?’

Thus speaks the Eskimo, the man who considers himself pre-eminently the ‘man,’ and who has not been taught that God made him, the sun, and the moon, and the stars also:

‘Long, long ago, not long after the creation of the world, there lived a mighty Eskimo, who was a great conjurer; nothing was impossible to him; no other of his profession could stand before him. He found the world too small and insignificant for his powers, so, taking with him his sister and a small fire, he raised himself up into the heavens. Heaping immense quantities of fuel on the fire, he formed the sun, which has continued burning ever since. For a while he and his sister lived together in perfect harmony, but after a time he began to ill-treat her, and his conduct towards her became worse and worse[49] until one day he scorched her face, which was exquisitely beautiful. This was not to be borne, she therefore fled from him, and formed the moon. Her brother is still in chase of her, but although he sometimes gets near her, he will never overtake her. When it is new moon the burnt side of her face is towards us; when full moon the reverse is the case. The stars are the spirits of the dead Eskimo that have fixed themselves in the heavens, and meteors and the aurora are these spirits moving from one place to another whilst visiting their friends.’

In school work and teaching Mr. Horden took from first to last the keenest interest. After he became bishop he still visited the Moose School daily, whenever he was in residence. In earlier years he had for a time the able assistance of a native master, Mr. Vincent. A small boarding-school had been commenced in 1855 with two children, who were supported through the Coral Missionary Fund.[1] The following year, two more children were taken, and in 1857 the number on the list amounted to eight; to these others were yearly added, supported by friends of the Coral Fund.

Little Susan was one of these. Her unfinished sampler with the needle in it was sent to England. The children’s histories were many of them very sad and pathetic. Some were orphans. The parents of others were disabled, or too sick and suffering to work. One little girl was described as having so wild a look that a portrait of her scarcely resembled that of a[51] human being. Another, after remaining for a time in the school, fell ill with the strange Indian sickness called ‘long thinking,’ a gypsy-like yearning for the wild life of the forest, and she had to be sent back to her widowed father. One boy died early of decline, a complaint to which the Indian is very subject. Another was the child of a father who lay sick and bed-ridden in a most deplorable condition—parts of his body actually rotten. ‘He might’ have been the Lazarus of the parable,’ wrote Mr. Horden. ‘He gets little rest night or day, but, like Lazarus, his mind is stayed on God.’

A few children having thus been gathered together with the certainty of support, Mr. Horden commenced building a school-house. He had from the first assembled the children for daily instruction, but to board and clothe them was impossible without some friendly help, all necessaries at Moose being nearly double the price of the same articles at home. At one time it was quite double. From this we may gather with what delight was hailed, as the season came round, the arrival of the annual ship, bringing to the missionary and his family the stores needed for themselves and their charges for the year to come.

In 1864 very especially, Mr. and Mrs. Horden awaited in eager expectation the ship’s appearance, for not only did they long to know that the wants of the school children and the poor who depended upon them would be supplied, but they were hoping themselves to return in her with their little family for a[52] well-earned rest and change in England, from which country they had then been absent thirteen long years. The three elder children were of an age to need an English education. The little son, a boy of nine or ten, whose principal amusement was to go to the woods with an axe over his shoulder to cut firewood, must, ere it was too late, be weaned from the free life in the forest, and begin to measure his powers of mind and body with other lads of his age and class at home. The wife and mother yearned to see the relatives parted from long ago; the hard-worked man hoped for stimulus and help in the society and sympathy of his brethren and fellow-labourers.

These hopes and yearnings were doomed to disappointment. ‘You know,’ wrote Mr. Horden on January 25, 1865, ‘that it was my intention to be at home this year, and I had expected to have reached England in October or the beginning of November. But August passed and the ship did not arrive, and anxiety increased daily. The 23rd came, the latest day on which the ship had ever been known to appear, and then we began to despond and to say, “No ship this year!” The schooner still remained outside, hoping against hope, until October 7. That same night, in the midst of a most fearful storm, we heard the report of large guns at sea; our excitement was extreme, our hopes revived, and from mouth to mouth passed the joyful exclamation, “The ship’s come! the ship’s come!” We lay down to rest, lightened of a great weight of anxiety, dreaming of absent friends, with a strange pleasant confusion of boxes, storms,[53] ice, guns, and the many other etceteras of the sailing, arrival, and unloading of our ship.

‘Morning dawned, the storm had subsided, a boat was despatched for letters, the schooner was again ordered to sea, all hearts beat high, and by ten o’clock our illusions were dispelled. The guns had been fired by the York schooner, which had been despatched to Moose to acquaint us with our misfortune, and to bring the little that had been saved from the wreck. It was very little, yet sufficient to remove anxiety as to our living for this winter, as we thus became possessed of flour and tea, which we can only obtain by the ship, for in our wintry land no fields of wheat wave their golden heads, and no sound of the reapers ever falls upon the ear. Of the many packages sent me, the Coral Fund box was the only one which came to hand, all the rest are at the bottom of the sea: and of the contents of your box, everything was much damaged, except the service book, now lying on the communion table at Moose. The packet-box was saved, which accounts for my receiving your letter.

‘The Moose ship left England in company with the Hudson’s Bay Company’s ship, bound for York Factory, which is a post about seven hundred miles north of Moose, and came across the Atlantic and nearly through Hudson’s Straits without any mishaps. On August 13 the two ships were together, a few miles to the east of Mansfield Island; the captains visited and congratulated each other upon having passed the most dangerous portion of the voyage,[54] and expected that within a week the one would be at York and the other at Moose. But how blind is man! Within a few hours both of them were ashore on Mansfield Island, about twelve miles distant from each other. The York ship had a very large number of men on board, and by almost incredible exertions she was got off, but not until she had sustained such damages as necessitated the constant use of the pumps. The Moose ship could not be got off, and still lies with nearly all her valuable cargo on the rocks. The York ship came to her and took all the crew on board, together with what had been saved, and proceeded to York Factory. There she was examined, and then it appeared how near all had been to death; the wonder was how she could possibly have kept afloat. To return to England in her would have been madness, so she still lies at York. Happily a second vessel had gone to York, which took home nearly the whole of the crews of the two disabled ships.

‘When I last wrote I asked for the service book for my new church; that edifice has now, I am happy to say, been opened; the interesting ceremony took place on Whit-Sunday, May 15, 1864. The ice had entirely disappeared from the river; the sun shone forth brilliantly, all Nature smiled. A large congregation assembled at our usual hour for service, and all seemed impressed with the solemnity of the occasion. The subject of the sermon was the dedication of Solomon’s temple. At its close the collection amounted to upwards of 4l., and after that a number[55] of Europeans, natives, and Indians, assembled round the table of the Lord. It was the first time I ever administered a general communion, many of the Indians not understanding English; but on this occasion I wished them to see that, in spite of diversity of language, God is alike the God of the white man and the red. Altogether it was a most interesting and happy day. It is literally a church in the wilderness. I hope it will not be long before others rise in this part of the country.

‘I have lately heard of my poor Eskimo brethren in the far-off desert; that infant church has been much tried. Just one half of its members have been carried off by death; there were but four, two of whom are gone, and both somewhat suddenly. One of them was the young Eskimo interpreter, who when I was last with them was of such very great service to me. Late in the fall he went off in his kayak to set a fox trap. He did so, but as he was getting into the canoe to return home it upset with him, and the coldness of the water prevented him from swimming. His body was not discovered until the evening of the following day. The other was the only baptized woman, her name was Elizabeth Horden. These trials must be necessary, or they would not be sent.’

In 1865 Mr. Horden and his family came home; the journey was a long and very anxious one. ‘Among the many dangerous voyages which our bold sailors undertake,’ he writes, ‘there is none more dangerous, or attended with more anxiety, than the one to or from Moose Factory. Hudson’s Straits are dangerous, Hudson’s Bay fearfully so, James’s Bay worst of all. It is full of sunken rocks and shoals; it is noted for its fogs.

‘When the ship came, it was in a somewhat disabled condition, so severely had she been handled by the ice. However, we repaired her at Moose, and although it was very late in the season we determined, putting ourselves in God’s hands, to trust ourselves in her. We left Moose with a fair wind, which took us in safety over our long, crooked, and dangerous bar; but we had not proceeded above half a day’s sail before a heavy storm came upon us. Dangers were around us, the dread of all coming to Moose Factory, the Gasket Shoal, was ahead; the charts were frequently consulted; the captain was anxious, sleep departed from his eyes. We are at the commencement[57] of the straits; we see land, high, rugged, barren hills; snow is lying in the valleys, stern winter is already come; it seems a home scarcely fit for the white bear and the walrus. What are these solitary giants, raising their heads so high, and appearing so formidable? They are immense icebergs which have come from regions still farther north, and are now being carried by the current through Hudson’s Straits into the Atlantic Ocean. The glass speaks of coming bad weather, the top-sails are reefed, reefs are put to the main-sail; and now it is on us, the wind roars through the rigging, the ship plunges and creaks. Night comes over the scene, there is no cessation of the tempest; it howls and roars, it is a fearful night! One of the boats is nearly swept away, and is saved with difficulty; we have lost some of our rigging; one man is washed overboard, and washed back again. The sea breaks over the vessel, and dashes into the cabin; but One mightier has said, “Hitherto shalt thou come, and no farther.” By the morning, the morning of the Sabbath, the wind had abated.’

Dreary weeks followed; the time for arrival in England had long since passed, and our travellers were still beating about in the Atlantic. Luxuries had vanished, comforts had departed, necessaries were becoming very scarce, and they began to ask each other, ‘Is England ever to be reached?’ Then the children saw a steamer for the first time in their lives, and their surprise was great; and now they pass vessel after vessel. They are running up the English Channel, a pilot comes on board, and on they[58] go, till they are safely moored in the West India Docks. Now to a railway station and into a railway carriage, out of that and into a cab through the busiest part of London; the shops are brilliantly lighted up; the children are at the windows, their exclamations of surprise are incessant, a new world is opened to their view—a world of bustle, a world of life.

Mr. Horden spent a busy year in England, travelling, as he expressed it, ‘from Dan to Beersheba,’ speaking on behalf of ‘his beloved people’ and his work; everywhere eliciting sympathy and interest. In his absence from the station Mr. Vincent of Albany had gone to Moose, to provide for the spiritual wants of the flock and to keep the school going. The children were examined before the Christmas holidays in Scripture and Catechism and arithmetic, after which they were rewarded with little presents sent in the bales from England. He reported the mission as presenting a cheering aspect. ‘From every quarter,’ he writes, ‘the heathen are being gradually brought under the influence of the Gospel; we have much cause for encouragement, but we also meet with opposition. I visited an outpost in the Rupert’s River district last summer, about five hundred and fifty miles distant from this station, called Mistasinnee. Both there and on the way I had frequent opportunities of preaching the Gospel to anxious inquirers, and before leaving that post I had forty-eight baptisms, half the number being adults; the trip occupied about two months. We are having a very mild winter, but not a favourable one for living, as rabbits and[59] partridges are very scarce. Sometimes we have a difficulty in making up something for dinner. I hope, however, as the season advances, we shall do better, for partridges then will be returning to the northward, and we may get a few in passing.’

At the end of the year Mr. Horden returned to Moose with his wife and two youngest children, and that same year the homeward-bound ship was once more in imminent peril. And now our hero began a series of long journeys, the longest he had made—one occupying three months and covering nearly two thousand miles—amongst people of various languages. He thus vividly describes it:

‘I left Moose Factory for Brunswick House in the afternoon of May 20, 1868. The weather was very cold, and on the following morning we left our encampment amidst a fall of snow. All along the river banks the ice lay piled up in heaps, occasionally forming a wall twenty feet high. This ice was very detrimental to our progress; it prevented the Indians from tracking the canoe, so that they were forced to use the paddle or pole, which is harder work and does not permit of such rapid progress. We got on pretty well until we came to where the river rushes with awful rapidity between high and almost perpendicular rocks: it certainly appeared like travelling to destruction. We had to cross the river several times,[61] so as to get where the current was weakest. We had crossed twice, and bad enough it was each time; we were to cross the third time; our guide demurred. It could not be done with safety; we should be driven down a foaming rapid and destroyed.

‘But it was now just as dangerous to go backward as forward, so, after a little persuading, the old man was induced to try. I took a paddle, and we got out into the middle of the stream, paddling for our lives; we were carried a considerable way down, but the other side was reached in safety. Then we poled, or tracked, on, as we best could, very slowly, until we had to cross again, and so on until the first portage was reached. Over this we plod, and again our canoe floats into the river; then pole, paddle, or track until a majestic fall or a roaring rapid warned us to make another portage; and so on, again and again, day after day.

‘As we went towards the south we actually saw some trees beginning to bud. On the very last day of May, in the afternoon, I reached Brunswick House. It is situated on a beautiful lake, the whole establishment consisting of about five or six houses; it is a fur-trading post. The Indians speak the Saulteaux language; there are about a hundred and fifty of them here; they are quiet and teachable, but given to pilfering and very superstitious. To comfort they seem to be strangers, lying about anywhere at night, their principal resort being the platforms near the trading-house. I believe that God’s blessing rested on my labours among these Indians. This was their[62] first introduction to the Christian religion, and I trust that ere long many will be numbered among Christ’s disciples.

‘After remaining with them nine days, I was obliged to hurry northward. Our progress was rapid, the water was in good order. A few days at Moose, and I went to the sea-coast to Rupert’s House. I found between three and four hundred Indians assembled there, under the guidance of their teacher, Matamashkum. Our joy was great and mutual; they have been heathens, many of them have committed horrible crimes, but those days have passed away, and now they rejoice in the merits of a Crucified Saviour. Twice every day we had service, almost out of doors, for there was no available room at the place capable of containing all. During the day I had examinations, and baptisms, and weddings, and consultations; and one afternoon we had a grand feast, for the Indians had made a good hunt, and the fur-traders, delighted with what they had done, provided the feast for them. There was nothing of dissipation. Eating and drinking was quite a serious matter with them, and it was astonishing to see the quantities of pea-soup, pork, geese, bread, biscuit, tobacco, tea and sugar, they consumed; the providing a body of Indians with a good feast is no light matter.

‘Having spent two Sundays at Rupert’s House, I took canoe and went to Fort George, northwards along the sea-coast. For a portion of the way I had company, as many Indians were also going north.[63] This was the most pleasant of all the journeys; the weather fine, the scenery often grand, the wind fair. Two hundred miles were made in four days and a half. At Fort George I met a good body of Christian Indians with their teacher, William Keshkumash.

‘A few days here, and I embarked on board a schooner, to go yet further north, to Great Whale River. Soon after getting out to sea we were among the ice; however, on we go. It is the sea, but there is no water! We are in an Arctic scene; we cannot go through, so we turn our head for Fort George again, and wait there for nearly another week, and then try once more. We get half way, then, as the vessel cannot move forward, I leave it, and accompanied by two native sailors proceed in a small boat. Two days bring us to an encampment of Indians. I now leave my boat and enter a canoe, having with me Keshkumash, his wife, and their young son; two other canoes, each containing a man and his wife, keep us company. We have to work in earnest. Sometimes we got along fast, then we were in the midst of ice and could not move at all, again we were chopping a passage for the canoe with our axes; and then, when we could do nothing else, we carried it over the rocks and set it down where the ice was not so closely packed.

‘After two days and a half of this we came to a standstill, and I determined to go on foot. I took one Indian with me, and we set off. Our walk was over high bare hills; rivers ran through several of the valleys, these we waded. About ten o’clock that night I sat[64] down once more in a house, very, very tired, and very, very thankful. I spent several days with the Indians of this place; they are a large tribe of Crees, but speak somewhat differently from those of Moose. Most of them believed the words that were spoken, but some cared for none of those things, being filled with their own superstitions.

‘By-and-by the schooner Fox made her appearance, and I embarked once more, to endeavour to get to the last inhabited spot, Little Whale River. We went half way, and then the ice sent a hole through the Fox’s side; this we covered with a sheet of lead. I now again deserted the Fox, and took to the canoe, in which, in somewhat less than two days, I got at last to my journey’s end. And that journey’s end is a dreary, dreary place, with scarcely any summer. It was August, and the ice was lying thick at the mouth of the river. But my work was not dreary. I here met Eskimo, the most teachable of people. They were very ready for school or service, and although their attainments were not high, so much was I impressed with their sincerity and perseverance, that I admitted four families into the Christian Church. This rewarded me for all my toil. I can address them now as brothers and sisters; and I am sure that all my friends will rejoice with me for the blessing with which God crowned my labour.

‘I had my difficulties in getting back again; ice still disputed our progress, but on August 30, late in the evening, the trusty Fox, battered and bruised, came to anchor at Moose Factory, and I had the[65] happiness of once more meeting my family, and of finding that all had been quite well during the whole of my absence.’

About this time Mr. Horden began to plead for help to train up one of the most promising of his school-boys as a catechist. Friends of the Coral Fund took up the lad, and the money expended upon his education was not in vain, for that boy is now a native pastor in charge of Rupert’s House. Of him and of his ordination we shall have more to relate by-and-by. The school children in whom Mr. Horden had first taken an interest were growing up. Some were already earning their living, some were married; one girl had gone with her husband to the Red River settlement, and was, wrote Mr. Horden, in 1869, in as respectable a sphere of life as any Christian farmer’s wife in England could be. Another had married a fine young Moose Fort hunter, an excellent voyager. After an absence of several months, they with their little child came back to the place, stayed a few days, and again departed. In May, at the breaking-up of the river, the Indians came in. One canoe Mr. Horden felt sure was that of Amelia and her husband, and he at once went to see them.

‘I saw,’ he says, ‘first a fair little boy, plump and hearty, showing that great care had been taken of him. I then cast my eye on a woman sitting near, whom I took to be a stranger; but another look showed me that the poor emaciated creature was indeed none other than Amelia, who had been brought to the brink of the grave by starvation. She[66] had lost her husband, but in all her privations she had taken care that her baby son should not want. The tale of her suffering was very distressing. After leaving Moose in the end of March, they by themselves had gone to their hunting-grounds, hoping to get a few furs to pay off the debt they had contracted with the fur-trader; for in the early part of the winter they had been very unfortunate, a wolverine having destroyed nearly all the martens they had trapped. Amelia’s husband was soon attacked by sickness, which entirely laid him by; food was very scarce, and the little the forest might yield he could not seek. He gradually became worse and worse, his sufferings aggravated by want, his only source of consolation was his religion; both expected to lay their bones, as well as those of the child, where they were. He wrote a letter, and got Amelia to go and hang it up where some Indians might pass in the summer, stating their joint deaths and the cause, and requesting burial. The end came, the once strong young man lay a corpse; but Amelia had something to live for—for her little son she would struggle on. Unable to dig a grave, for she had no strength and the ground was frozen as hard as a stone, she covered the body with moss, and set off to the Main Moose River, hoping there to fall in with Indians. She was not disappointed. After a while she fell in with Isaac Mekawatch, a Moose Indian, who took care of her and her child, and brought them in safety to the fort. Such incidents as this are amongst the sad experiences of life in Moosonee.’

In 1870 Mr. Horden wrote: ‘I have this summer travelled about thirteen hundred miles, and during a part of this time I experienced a considerable degree of hardship, which brought me down greatly. I am now, however, well as ever I have been in my life. It was a very long journey, and occupied many weeks, yet I did not travel out of my parish all the time. When I was at Matawakumma, five hundred miles south of Moose, I was upwards of eleven hundred miles from Little Whale River.

‘I left Moose on June 13, and overtook a boat going to the Long Portage, with goods for the supply of New Brunswick, and I went forward in it. Travelling by boat is very monotonous work indeed. At breakfast-time, dinner-time, and when the day’s work was done, we endeavoured to catch a few fish, our rod a long rough stick cut from the woods, a piece of strong cord for a line, to which we attached a large hook baited with salt pork; with this we would occasionally draw out a perch, a trout, a pike from six to twelve pounds in weight. At the Long Portage I changed my mode of travelling, my companions now using the canoe. With my new friends I got on extremely well, taking advantage of every opportunity to instruct them in divine things. Most of them received the instruction gladly, but a few held back; they love their old superstitions, their conjurations, dreams, spirits, and all the other things which so sadly debase the Indian mind. In due time New Brunswick was reached, and I at once began my work.

‘The Indians here, before they had ever seen a missionary, used to meet for prayer and exhortation, having learnt a little from an Indian who had seen one. Desirous of knowing how they conducted their service, about which I had heard a great deal, I arranged one evening to be present as a spectator. They showed no shyness, but consented at once.

‘At the time appointed, all being assembled, one gave out the verse of a hymn, which was sung by all; another then repeated a text of Scripture, then a second verse of the hymn was sung, followed by a second text; all then knelt down, I by the side of the old chief, and about six began to pray aloud at the same time, each in his own words. Ojibway’s prayer was very simple, of course, but it was a cry to Jesus for mercy; and can we doubt that his prayer was heard? Kneeling by his side was one sent by God to show him the way of salvation.

‘One of those who opposed the Gospel said: “I would not give up my children to you for baptism on any account. My eldest child has been twice so ill that I thought she would die, but an Indian, by his charms, saved her; and recently a spirit appeared to me, telling me to take heed and never give up my children, for if I did, he would no longer take care of them, and they would die.”

‘I remained at Brunswick until the Indians departed to Michipicoton for supplies of flour. I went with them a little way, and then on to Flying Post by a road untrodden by any save the Indian on his hunting expeditions. I found it a terrible route—the[69] worst I have ever travelled—but having no one to think of but myself, I did not mind it—I was about my Master’s business. In due time we reached Flying Post. Our last portage was eight miles of truly horrible walking; it cost us many weary hours.

‘The Indians of Flying Post evinced a great desire for instruction. This was my first visit; I baptized seventeen persons. From Flying Post I went on to Matawakumma. At Matawakumma the Indians are decreasing, as at Flying Post. The decay of a people brings sad reflections, and the Indians seem doomed to extinction. I found a church partly built under the guidance of their trader, Mr. Richards, who takes a deep interest in his Indians’ welfare. A bell and a set of communion plate I hope to get out next ship time; the little church in the wilderness will then be tolerably well furnished.

‘I here made the largest comparative collection I have ever made in my life, no less than 8l. 2s. 8d. The poor people were truly liberal in their poverty, and some of these poor sheep for the first time approached the table of the Lord. Some of them are very intelligent, can read well, and thoroughly understand their Christian responsibilities and appreciate their privileges. And now, my work done, I turn my canoe-head Mooseward, and pass over grand lakes, down a large river, run the rapids, admire the falls, carry over the portages, hurrying towards the sea, and after an absence of between eight and nine weeks I found myself once more in the bosom of my family.’

Nothing perhaps could give a better idea of Mr. Horden’s gigantic labours than an account of a day’s work at different times. A Sunday in the winter of 1871 is thus spent by him.

‘While it was yet dark,’ he says, ‘at half-past six o’clock the church bells summoned us to the house of prayer; the cold was severe, but I found a tolerable congregation awaiting me, and the service was very enjoyable. The congregation dismissed, I returned home to breakfast, and soon afterwards went to the church again for our English service. This is conducted precisely as in a church at home; the full service is read, and we use one prayer which you do not, for the Governor-General of Canada and the Lieutenant-Governor of the Hudson’s Bay Territories. The congregation is composed of the deputy-governor, his family and his staff of clerks, and the doctor—not one of whom is ever absent, and all but one are communicants—my own family, and the servants European and native of the Hudson’s Bay Company. After the sermon a general offertory was made, and then the communicants met around the[71] Lord’s table, there to renew their vows, and to partake of that spiritual food which was ordained to strengthen them in their heavenly course.

‘At a quarter to two the bell was rung for school, and a few minutes after I was with the scholars, on my knees seeking a blessing on our meeting together. School over, our second Indian service commenced with a larger congregation than in the early morning, for young children can be brought out now. There is again a departure from the church, yet some remain, and those, as their English-speaking brethren had done in the morning, commemorate their dying Saviour’s love. In all thirty have communicated. The shades of evening are falling as I leave the church, after a fatiguing, but blessed day’s work.’

The necessity was laid upon Mr. Horden of being like St. Paul, ‘in journeyings oft,’ and the day’s work we have now to speak of was one of journeying.

‘Last summer,’ he says, ‘I was on my way to Rupert’s House. A large boat just built was going there, and I took a passage in it. It was loaded with a miscellaneous cargo of bricks, potatoes, a stove, bags of flour, and bales of goods. The crew was composed of Rupert’s House Indians, fine manly fellows, and all Christians. Leaving Moose somewhat late in the day, we went but a short distance and encamped on an island, eight miles off, called Ship-sands. Here we set up our tent and cooked our supper; then we gathered together, and joined our voices in a hymn of praise. I read a portion of Scripture, and we all knelt in prayer to the God of heaven and earth, and[72] not long after lay down to rest. At midnight there was an arrival, and I was aroused from sleep by my guide, with the cry of “Musenahekun! Musenahekun!” A packet! a packet! These are magic words. I started to my feet in an instant, for not since February had I seen a letter from home, and it was now June 17. It was, however, but a poor affair, containing no private letters from England, and but little public news. The real packet I welcomed at Rupert’s House nearly a month later.

‘In the early morn we spread our sails to the wind and went joyously forward. The east point of Hannah Bay is reached, and it now seems that further progress is impossible; there is ice, ice; block after block is pushed aside; hoisting sail, back we go, to round a projecting point. We are in a narrow, crooked lane of water, through which we move very carefully, with poles in hand, ready to do battle with any piece of ice which lies in our way, and so hour after hour slips by, and all hopes of reaching Rupert’s House are at an end; but towards evening our labours are crowned with success, and the clear sea stretches before us. There is no place to land. We set our best man at the helm, and taking reefs in our sails, trust to the protection of the Almighty. I think it was the most uncomfortable night I have ever spent.