Transcriber’s Note

This ebook contains several wide tables that may display poorly on some e-readers. The HTML version may be a better option for viewing these tables.

[Pg i]

BY

A. K. McCLURE, LL.D.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK AND LONDON

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

1900

[Pg ii]

Copyright, 1900, by A. K. McClure.

All rights reserved.

[Pg iii]

[Pg v]

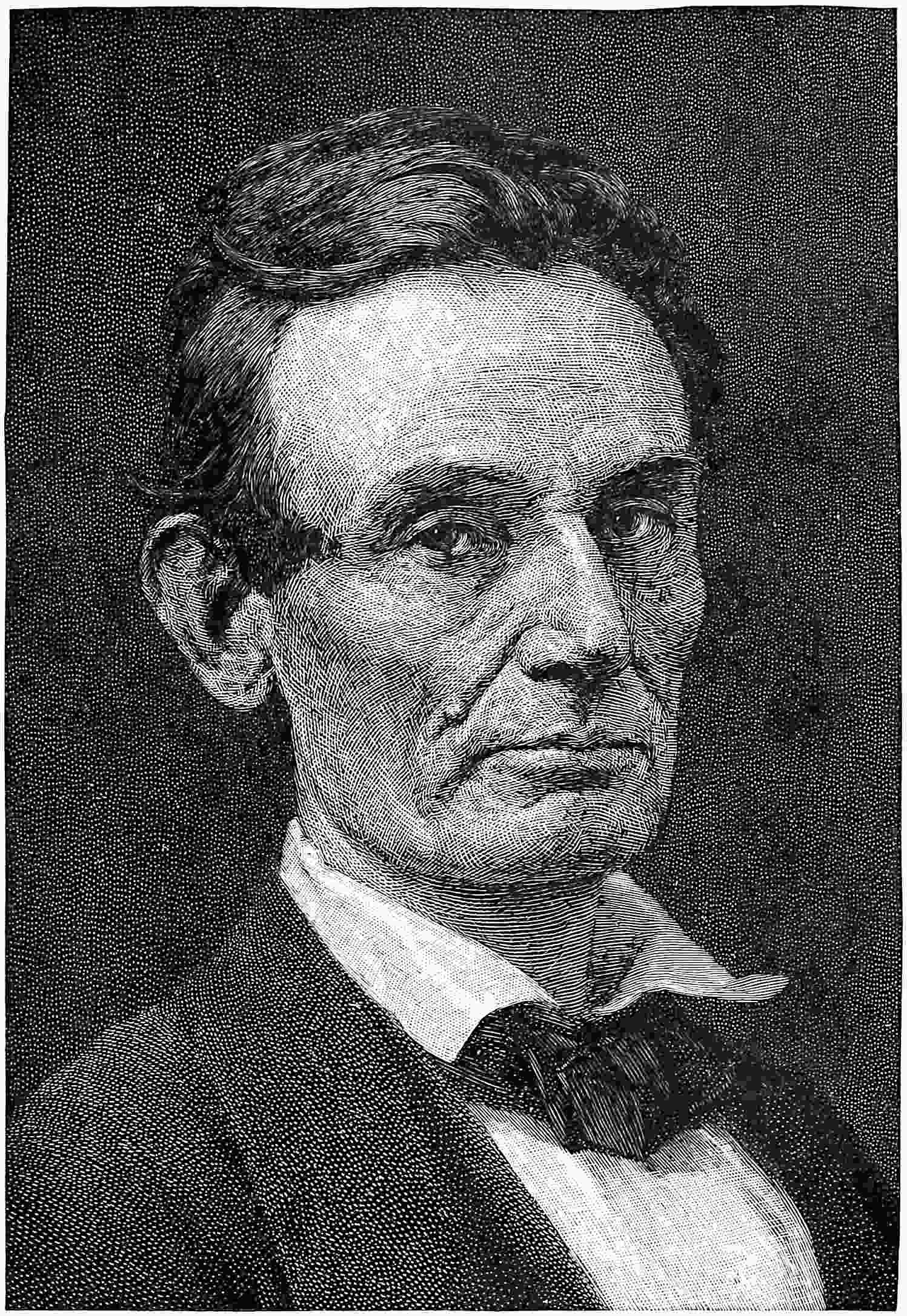

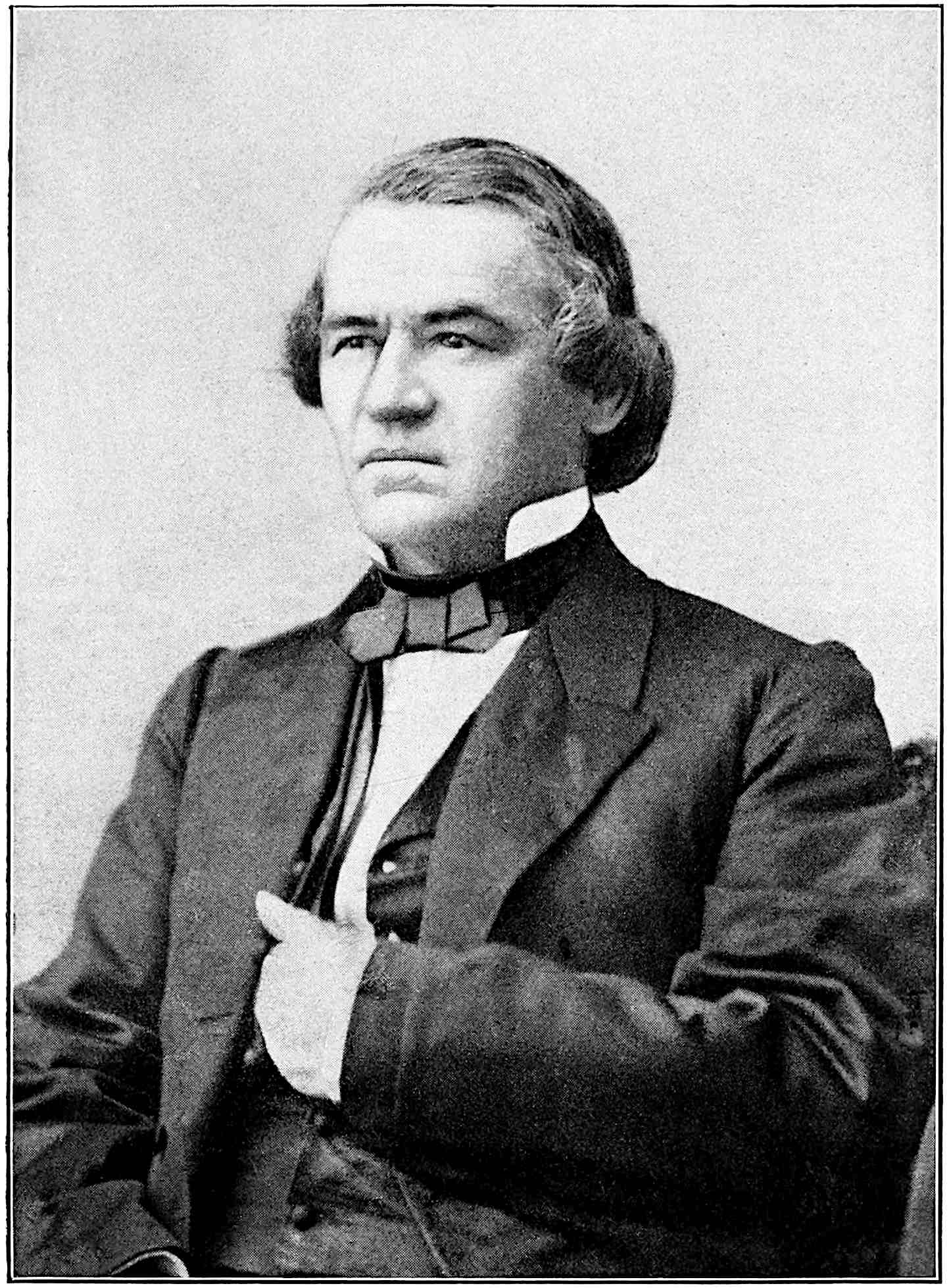

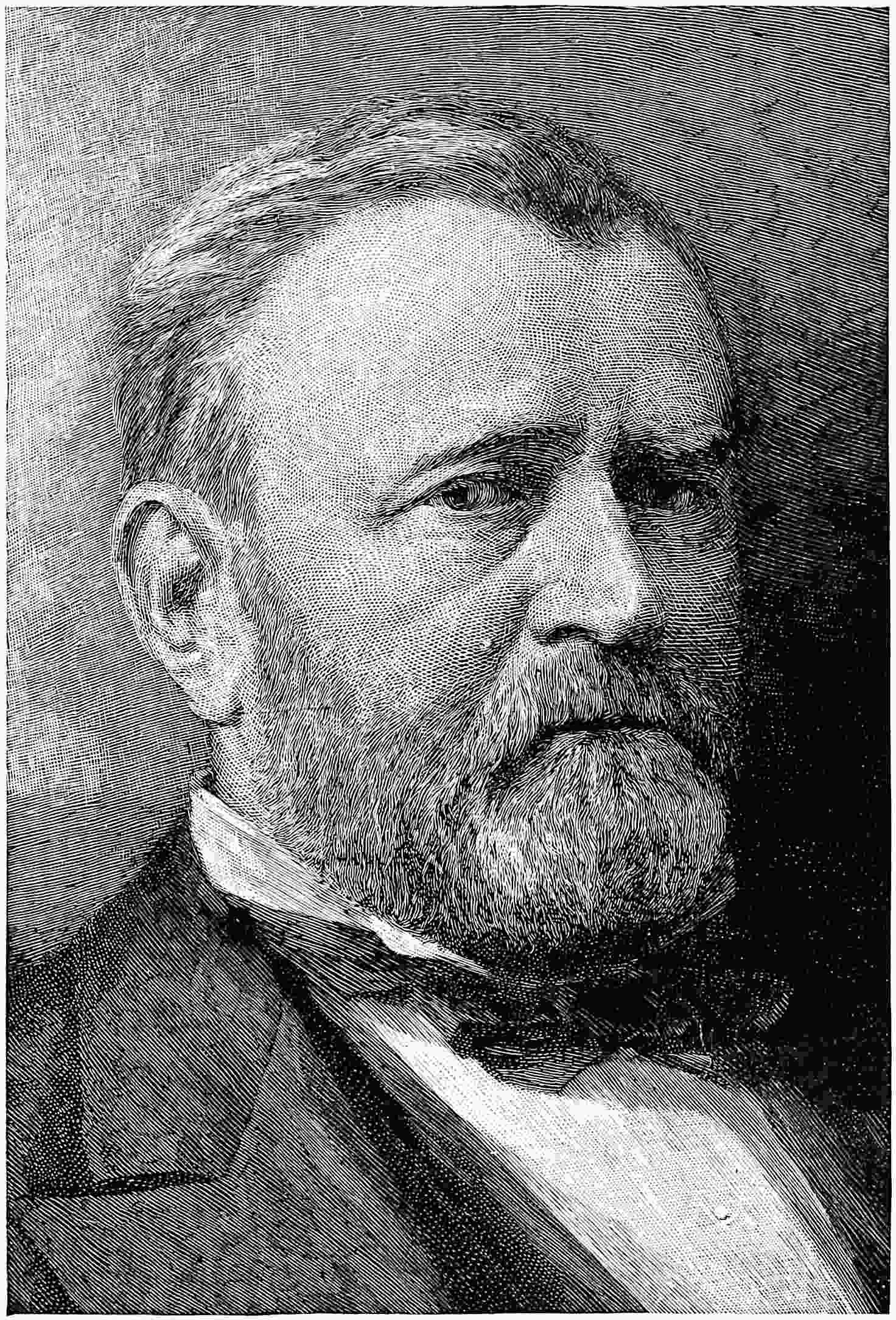

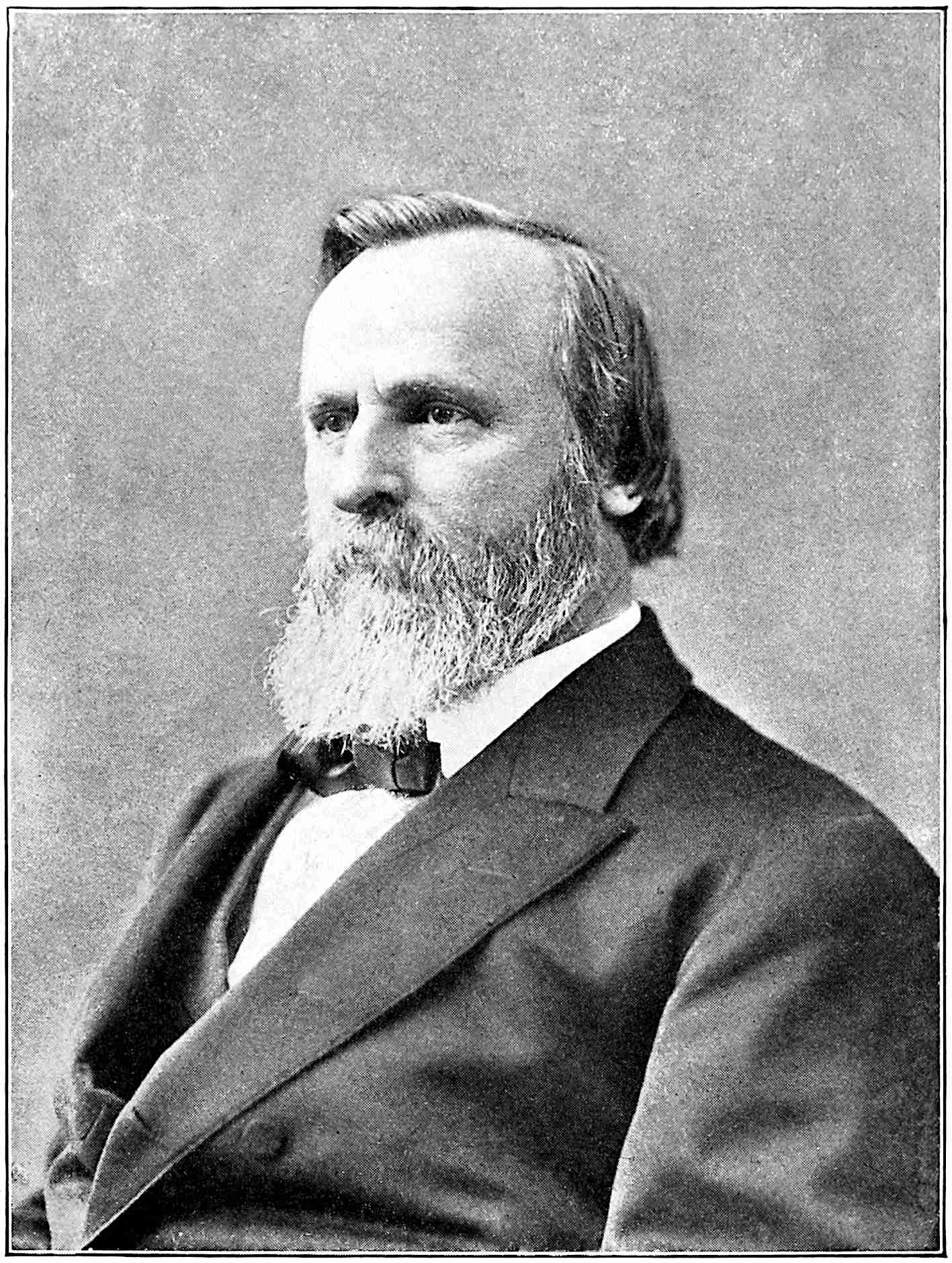

| A. K. McCLURE | Frontispiece | |

| GEORGE WASHINGTON | Facing p. | x |

| JOHN ADAMS | “ | 12 |

| THOMAS JEFFERSON | “ | 20 |

| JAMES MADISON | “ | 24 |

| JAMES MONROE | “ | 32 |

| JOHN QUINCY ADAMS | “ | 38 |

| ANDREW JACKSON | “ | 46 |

| MARTIN VAN BUREN | “ | 58 |

| WILLIAM HENRY HARRISON | “ | 64 |

| JOHN TYLER | “ | 70 |

| JAMES K. POLK | “ | 74 |

| ZACHARY TAYLOR | “ | 94 |

| MILLARD FILLMORE | “ | 106 |

| FRANKLIN PIERCE | “ | 114 |

| JAMES BUCHANAN | “ | 130 |

| ABRAHAM LINCOLN | “ | 154 |

| ANDREW JOHNSON | “ | 182 |

| ULYSSES S. GRANT | “ | 202 |

| RUTHERFORD B. HAYES | “ | 244 |

| JAMES A. GARFIELD | “ | 270 |

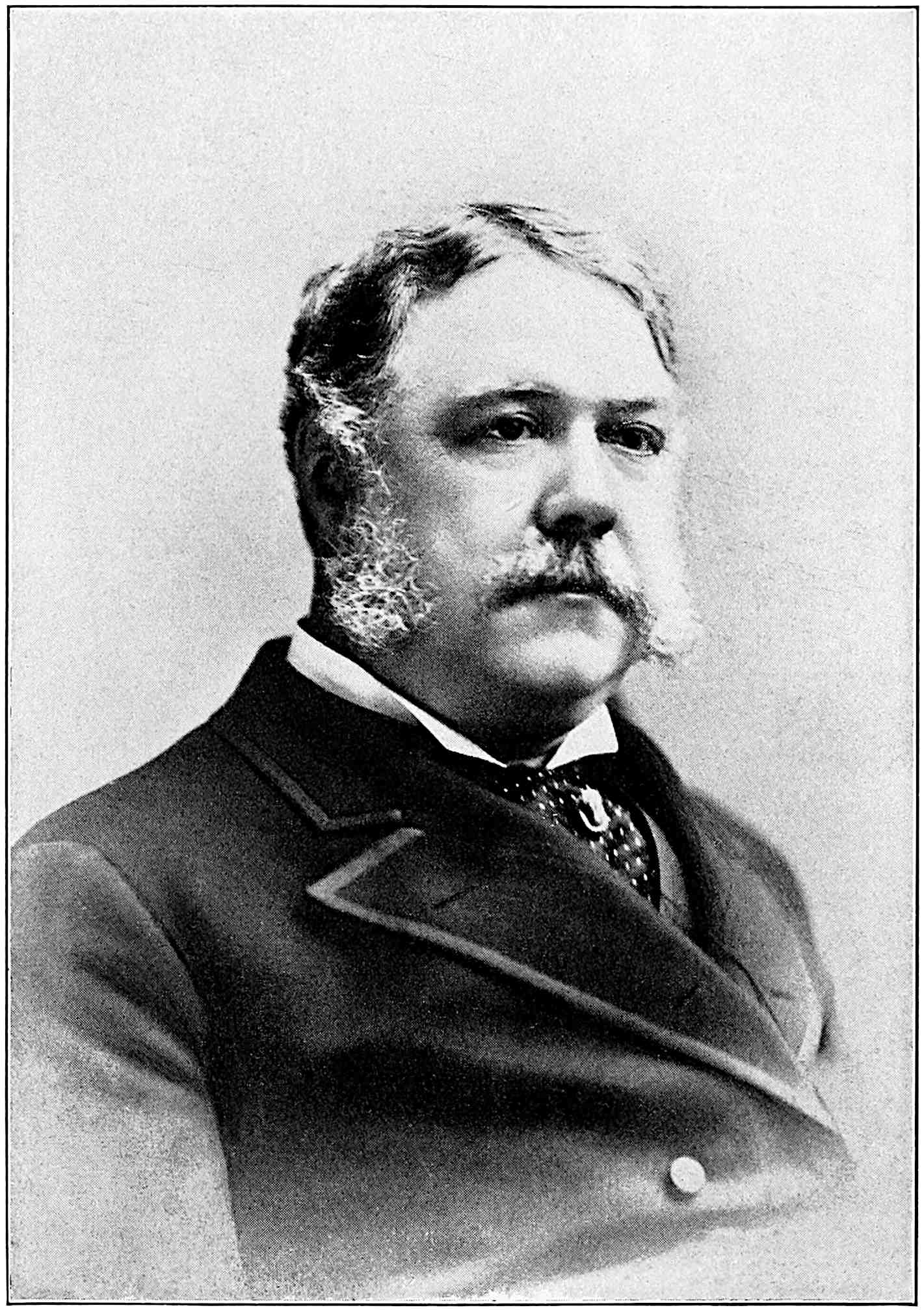

| CHESTER A. ARTHUR | “ | 274 |

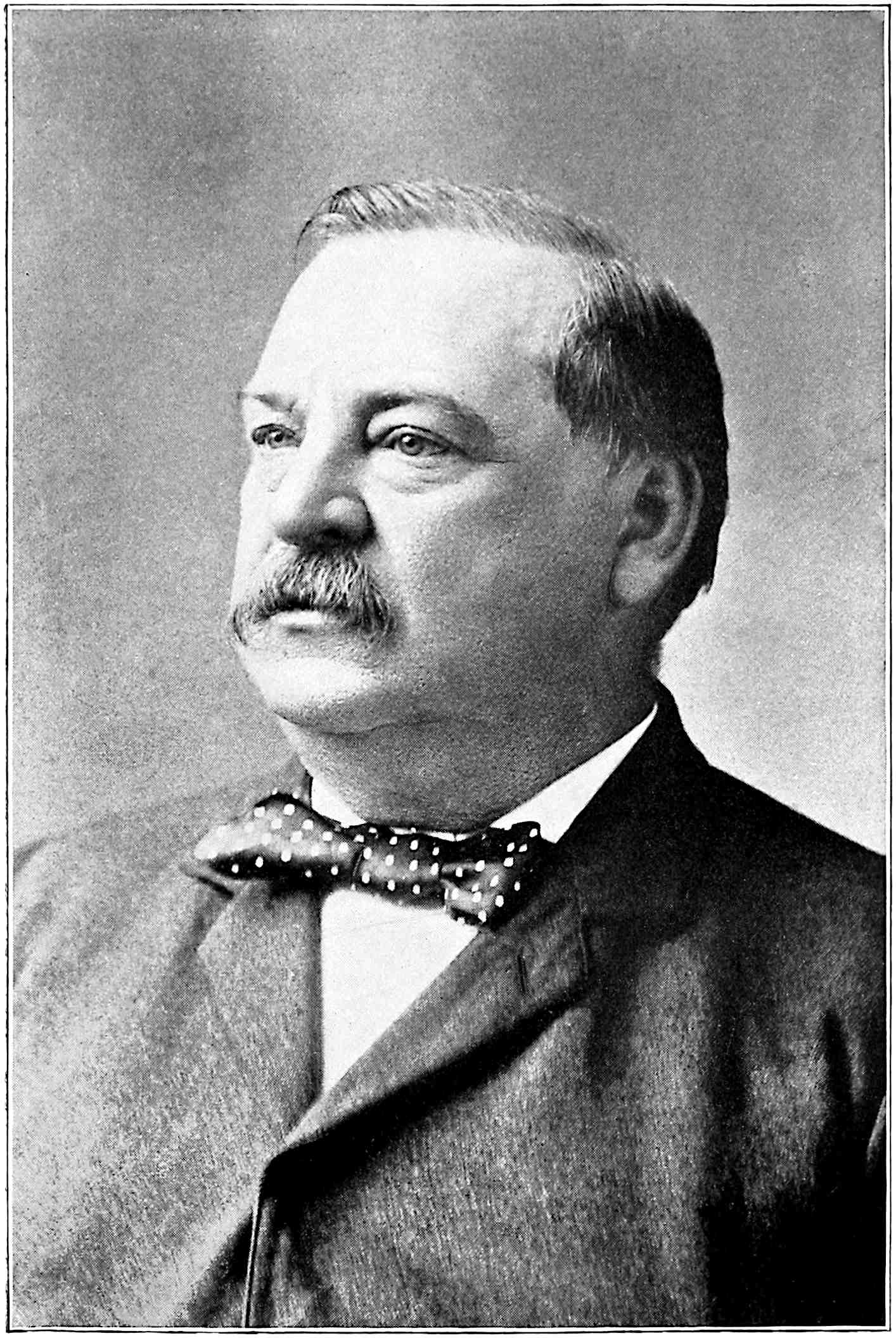

| GROVER CLEVELAND | “ | 288 |

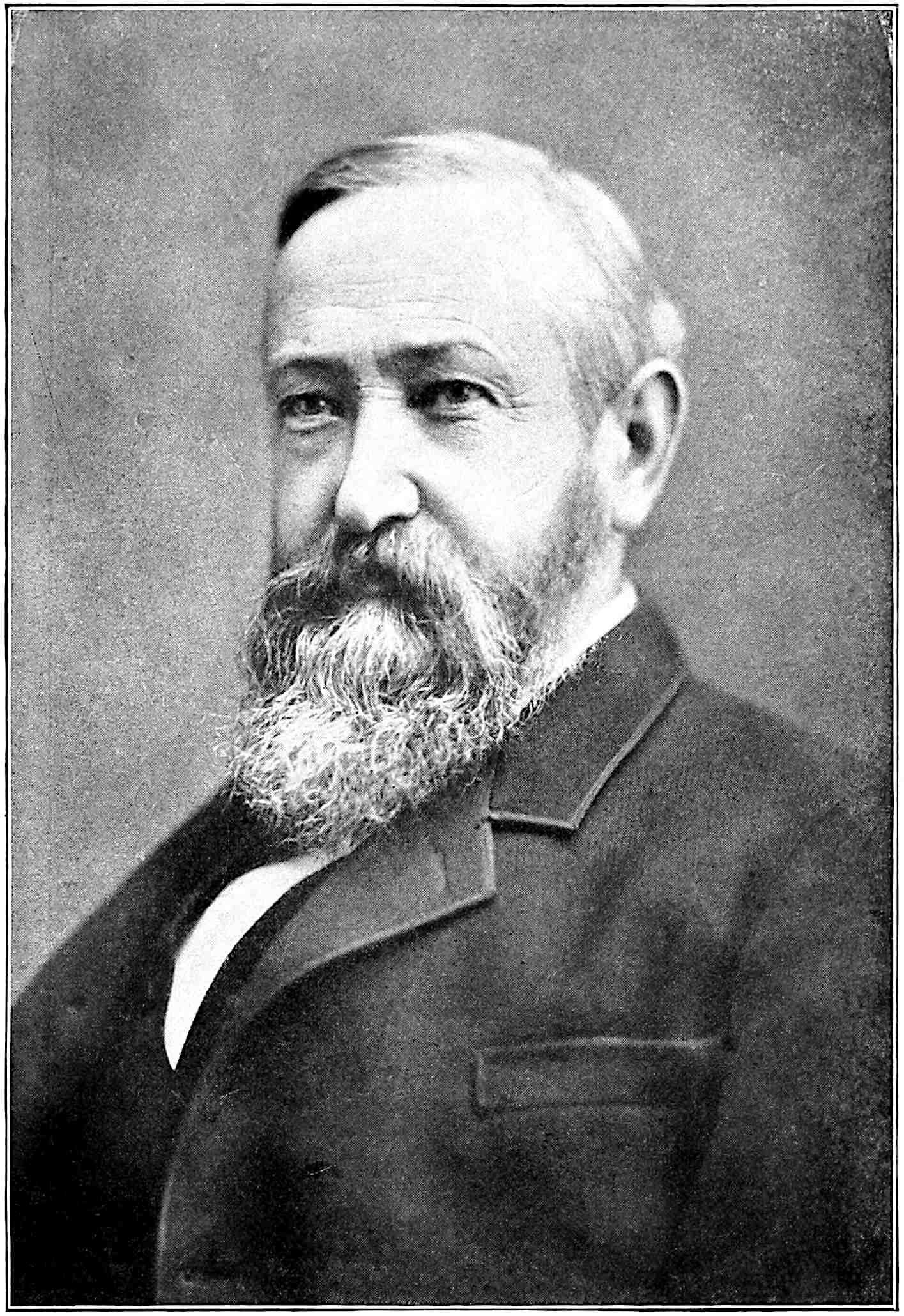

| BENJAMIN HARRISON | “ | 316 |

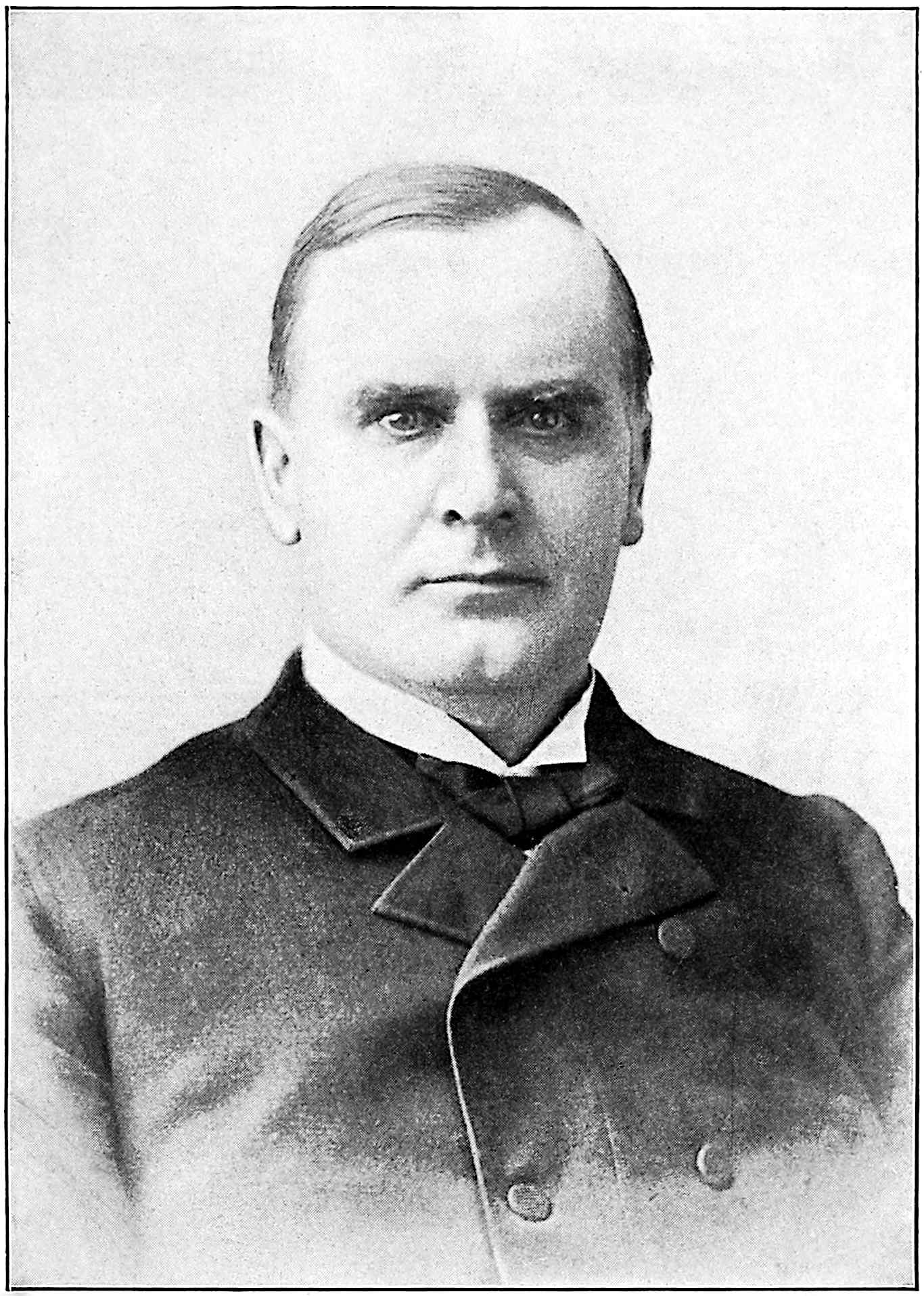

| WILLIAM McKINLEY | “ | 360 |

[Pg vii]

The crux of American politics is the quadrennial election of President. In the ebb and flow of our political activity the flood-tide comes in the Presidential contests. There are often tumultuous struggles and decisive events in the intervals, but their political effect and all the issues and movements of parties crystallize in the recurring conflict for the possession of the chief executive power.

Our American system makes the President the centre and focus of political life. He is at once Prime Minister and independent executive. He blends the functions of what in parliamentary government is the head of the Cabinet, and what in other government is the head of the State. He is a vital part of the legislative power without being amenable to its control or dependent on its life. He is the framer of policies and the arbiter of parties. All this makes the election of President the central chord and the arterial force of our broad political action.

The history of Presidential elections, if not the history of the nation, is at least the history of its determining periods. The successive epochs of our national progress, with their passionate struggles and controlling influences, are fully reflected in these contests. After the retirement of Washington the battles from 1800 for a quarter of a century, which gave the succession of Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe, marked the reaction from federal authority and the rise of the democratic impulse in the young Republic. Then came the period running through the three contests and two elections of Jackson, the heirship of[Pg viii] Van Buren, and the cyclonic reversal under “Tippecanoe and Tyler too” in 1840, which turned on practical questions of internal polity and signalized the transition from the formative stage of the government to the inevitable clash between the sections. This was followed by the long political and moral contention between freedom and slavery, which began with the success of Polk and the Texas annexation policy in 1844 and ended with the defeat of the divided Democracy and the election of Lincoln in 1860, when the political combat culminated in the armed and colossal struggle of the civil war. Since its conclusion and its settlements the nation has been engaged in the mighty work of internal upbuilding, never equalled anywhere else in the world, and the elections have involved the contending theories.

The narrative of these elections, with the rise and fall of parties, their divisions and their creeds, presents the outlines of the national development. For this work Colonel McClure, by experience, taste, and special knowledge, is peculiarly and pre-eminently fitted. It is doubtful if any other living American has borne so active and so intimate a part in so many Presidential elections. Not yet of age, but already a zealous and eager observer of political movements as a young editor, he attended the Whig National Convention of 1848 in Philadelphia, and witnessed the nomination of General Taylor. From that time he has been personally familiar with the inner workings of every national convention and campaign. Including this year, there have been twenty-nine Presidential contests in our history. Colonel McClure has actively participated in fourteen, or practically one-half of the entire number.

He was born at Centre, Perry County, Pennsylvania, on the 9th of January, 1828. Spending his youth on his father’s farm, he became a tanner’s apprentice at fifteen, and remained at this trade for three years. His schooling was very limited, and his mental equipment was almost wholly the rich endowment nature had given him and[Pg ix] the attainments which his extraordinary intellectual force brought in after-years. At nineteen he became the editor of the Juniata Sentinel, and his natural ability and vigorous pen soon gave him a recognized position and a distinct influence. Before he was twenty-one he served as a conferee for Andrew G. Curtin in his Congressional candidacy, and laid the foundations of his long and intimate friendship with the great War Governor. Speedily called to the editorship of a more important paper at Chambersburg, his impress broadened, and in 1853, at the age of twenty-five, he was nominated by the Whigs for Auditor-General, the youngest man ever named by any party in Pennsylvania for a State office. Four years later he was elected to the Legislature, serving in the House and then in the Senate for several years. His career in that body was brilliant and distinctive. He was independent, fearless, and aggressive, a ready and trenchant debater, and he displayed political and parliamentary abilities of the highest order.

In the Republican National Convention of 1860 he played a prominent part. He and Curtin were potential in leading the Pennsylvania break from Cameron to Lincoln, and in promoting the nomination of the latter. With that success he accepted the chairmanship of the State Committee, and made a dashing and energetic campaign, which resulted in the October State victory that assured and portended the election of Lincoln. This relation to the contest and subsequent service with Governor Curtin, in directing Pennsylvania’s part in the war, placed him on an intimate footing with the President, and during those dramatic and trying years he was a commanding figure in the State. Later he settled in Philadelphia in the practice of the law; became one of the leading spirits in the Republican revolt of 1872 which led to the Greeley movement; returned to the Legislature, where, free from party shackles, he waged unsparing war against jobbery and wrong, and where his forensic talent, his bold attacks,[Pg x] and rare powers of invective and sarcasm made him at once respected and feared. Finally, he found what was to prove his higher and truer place, and entered upon what was to be his main life-work in the establishment of the Philadelphia Times, where he has had an ample and conspicuous arena for the editorial genius which has ranked him among the foremost journalists of the country. Here, for twenty-five years, with ripened experience and mellowed spirit, but with unabated passion for political movements, Colonel McClure has been both the actor and the critic in the great and constantly changing drama of public events. Standing between both parties, bound by neither, but in the counsels of each, he has been exceptionally informed on all the currents of political activity. No one has had a broader acquaintance with the public men of his time, or has been more thoroughly behind the scenes in the shifting transformations of public action. From his earliest years politics has had an extraordinary fascination for his fertile mind, and his taste and talent for it have been equally marked. There has been no national convention of either party for years that he has not attended, and the episodes and influences which have turned the decision of the hour have been as familiar to him as the broader principles which have moulded the general course of action.

Colonel McClure is thus peculiarly qualified, not only to present the large history of Presidential contests, but to illuminate it with the instructive side-lights which are as entertaining as they are suggestive. Comprehensive in its treatment, infused with the very life and spirit of political action, prepared with complete knowledge, and written in a style of singular charm and force, this work is not only a labor of love, but a valuable contribution to the historical literature of American politics.

Charles Emory Smith

Washington, April, 1900

[Pg xi]

I have endeavored in this volume to supply a want in our political history by giving not only a detailed and reliable report of the nomination and election of every President of the United States, but by giving with it many important sidelights relating to the selection and character of our Chief Magistrates.

With a personal knowledge of national conventions covering over half a century, and an intimate acquaintance with the chief actors of both parties in selecting Presidential candidates, I am able to give the inside movements of some of our important national struggles which are imperfectly understood. The inspiration and organization of all the various political parties, great and small, are concisely presented, and the personal reminiscences of the struggles of the great men of the country have been most carefully prepared.

Absolute accuracy in the preparation of political history covering a period of one hundred and twelve years is not to be expected, as record evidence is at times either imperfectly preserved or entirely destroyed; but no pains have been spared to make this volume a complete and reliable history of our Presidents and how we make them.

I am indebted to Edward Stanwood’s “History of Presidential Elections” and to Greeley’s “Political Text-Book of 1860” for valuable data of the earlier conflicts for the Presidency. Many of the personal and political reminiscences given are an elaboration of a series of articles originally prepared for the Saturday Evening Post, of Philadelphia.

A. K. M.

Philadelphia, March 1, 1900.

[Pg xiii]

[Pg 1]

1789–1792

The first election for President of the United States was held on the first Wednesday of January, 1789, and it was an election in which the people took no part whatever in most of the States. The election should have been held in November, 1788, but the Constitution of 1787, that required ratification by nine States to make it the supreme law of the nation, did not receive the approval of the requisite number of States until the 21st of June, 1788, when New Hampshire made up the ninth State approving it. Vermont followed five days later, and New York, after a bitter struggle, ratified the Constitution on the 26th of July. There was then ample time for Congress to make provisions for a Presidential election in November, but many weeks were wasted in a struggle for the location of the national capitol, and it was not until the 13th of September that Congress was prepared to pass a resolution declaring the ratification of the Constitution, and directing the election of Presidential electors.

Communication was at that time very slow and uncertain between the several States, and as Congress did not fix the time for an election until the middle of September, the first Wednesday of January, 1789, was deemed the earliest period at which an election could be had. Considering the length of time required to communicate with the different States, and the extreme difficulty in the States communicating with their people and Legislatures, it was practically impossible to have a Presidential election in which the people of the country generally could participate.

None of the States had made any preparation for an election, and the only practical method for choosing electors was by the Legislatures, as the Constitution provided then, as it does now, that each State shall appoint Presidential electors[Pg 2] “in such manner as its Legislature may direct.” Attempts were made to hold popular elections in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia, but even in New Hampshire and Massachusetts, after elections had been held after a fashion, the Legislatures of those States finally chose the electors. There were next to no votes cast in Pennsylvania,[1] Maryland, and Virginia, as there was no contest, the election of Washington being conceded by all; and whatever votes were cast in the States have never found their way into the political statistics of the country. Rhode Island and North Carolina had not ratified the Constitution and did not choose electors, and in New York a bitter contest arose in the Legislature between the friends and opponents of the Constitution, resulting in a disagreement between the Senate and House that was not adjusted in time for the Legislature to choose electors. Thus, New York, Rhode Island, and North Carolina gave no votes for President in the Electoral College of 1789.

There had been no formal nomination of Washington for President and Adams for Vice-President in any part of the country. In later Presidential elections it was common for Legislatures and mass-meetings to present candidates for President, but I cannot find a record of any formal presentation of either the name of Washington or Adams as candidates at the first Presidential election. Washington was accepted as the logical ruler of the Republic, whose sword had won its independence, and Massachusetts, the State of Lexington and Bunker Hill, was conceded the second place on the ticket by general assent. Both were pronounced Federalists, and Washington was much more positive in his partisanship than is now generally believed. He was consulted about the choice of a Vice-President, and he answered that while he took it for granted that “a true Federalist” would be elected to the Vice-Presidency, he was unwilling to indicate any preference; but it was generally known that he and his immediate friends preferred John Adams, who had been one of the committee with Jefferson to prepare the Declaration of Independence, and who had written a very vigorous pamphlet in favor of the adoption of the Constitution.

It is now generally assumed that there was no shade of [Pg 3]opposition to Washington’s election to the Presidency, but the anti-Federalists, many of whom were opposed to the Constitution, made several ineffectual efforts to defeat him. It is known that Franklin was approached on the question of being Washington’s competitor, but there is little doubt that he peremptorily refused. At that time the Presidential electors did not vote directly for President and Vice-President as they do now. Each elector voted for two men for President, both of whom could not be a resident of the same State, and the candidate receiving the largest vote, if a majority, was chosen President, and the candidate receiving the second largest vote for President became Vice-President. Several movements were made, without ever attaining the dignity of importance, to have votes quietly taken from Washington and given to Adams, and other movements were made to defeat Adams for Vice-President, but all of them were signal failures. It is understood that Hamilton, the closest friend of Washington, was not friendly to Adams. There is some reason to believe that he would have seconded the movement of the anti-Federalists to make George Clinton Vice-President had it given any promise of success.

The electoral colleges met on the first Wednesday of February, 1789, and elected Washington President, he receiving 69 votes, being the full number of electors, and John Adams received 34 votes for President, which made him Vice-President, although he did not receive a majority of the electoral votes. The following table shows the vote in detail as cast by the Electoral College, all of the men having been voted for only as Presidential candidates:

| STATES. | George Washington. | John Adams. | Samuel Huntington. | John Jay. | John Hancock. | Robert H. Harrison. | George Clinton. | John Rutledge. | John Milton. | James Armstrong. | Edward Telfair. | Benjamin Lincoln. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Hampshire | 5 | 5 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Massachusetts | 10 | 10 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Connecticut | 7 | 5 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| New Jersey | 6 | 1 | — | 5 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Pennsylvania | 10 | 8 | — | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Delaware | 3 | — | — | 3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | —[Pg 4] |

| Maryland | 6 | — | — | — | — | 6 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Virginia | 10 | 5 | — | 1 | 1 | — | 3 | — | — | — | — | — |

| South Carolina | 7 | — | — | — | 1 | — | — | 6 | — | — | — | — |

| Georgia | 5 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 69 | 34 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

The Congress of the Confederation had provided that the new Congress chosen under the Constitution should meet in New York on the first Wednesday of March to declare the result of the Presidential election and inaugurate the new Republic, but a quorum of the Senate did not appear until the 6th of April, and on that day the electoral vote was counted in the presence of the two Houses, and Washington and Adams declared elected. They were notified of their election as speedily as possible, but it was not until the 30th of April that they were inaugurated.

Washington’s second election was quite as unanimous as the first, both at the polls and in the electoral colleges. No opposition electoral tickets were formed in any of the States, as the re-election of Washington and Adams was universally accepted. The Presidential electors of that day were appointed in accordance with the obvious spirit of the Constitution, that meant to provide an entirely dispassionate and independent tribunal in the Electoral College to exercise the soundest discretion in the choice of a President and Vice-President. No pledges were asked or given by any one named as an elector, and each one was free to vote according to the dictates of his own judgment. Had there been opposition electoral tickets, they would have logically run on opposing lines with distinct obligations on the part of each side as to how their votes would be cast, but no such question arose until the first battle between Adams and Jefferson in 1796.

[Pg 5]

There was no organized opposition to the administration of Washington at the close of his first term, but the Democratic sentiment, so ardently cherished by Jefferson, had been steadily growing, and with two such able and aggressive opposing partisans as Jefferson and Hamilton in the Washington Cabinet, it was only natural that opposition to the Federal policy would gradually take shape to be effective when the overshadowing personality of Washington became eliminated from the politics of the country. Jefferson and Hamilton often had serious differences in the Cabinet, and Washington uniformly sided with Hamilton. Washington had little personal and no political sympathy whatever with Jefferson, and only one of Jefferson’s rare tact and sagacity could have remained in the Washington Cabinet and fashioned the great opposition party that carried him triumphantly into the Presidential chair four years after Washington’s retirement. As opposition to the re-election of Washington and Adams would have been entirely fruitless, it was wisely not attempted, and the election passed off in almost as perfunctory a manner as did the first election in 1789.

Rhode Island and North Carolina had ratified the Constitution, and Vermont became a State on the 4th of March, 1791, and Kentucky on the 1st of June, 1792, giving fifteen States to participate in the second Presidential election. In nine of the States Presidential electors were chosen by the Legislatures, and by popular vote in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Maryland, North Carolina, and Virginia, but there were very few votes polled, and what were cast indicated nothing politically, as there were no opposing electoral tickets.

Washington again received the unanimous vote in the electoral colleges—132 in number—and Adams became Vice-President by receiving 77 votes for President. When the two Houses met to declare the vote, Vice-President Adams presided in the House, opened and read the certificates of the votes of the several States, and declared Washington and himself elected President and Vice-President. The following is the official vote in the electoral colleges as cast in 1792:

[Pg 6]

| STATES. | Washington. | Adams. | Clinton. | Jefferson. | Burr. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Hampshire | 6 | 6 | — | — | — |

| Vermont | 3 | 3 | — | — | — |

| Massachusetts | 16 | 16 | — | — | — |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 4 | — | — | — |

| Connecticut | 9 | 9 | — | — | — |

| New York | 12 | — | 12 | — | — |

| New Jersey | 7 | 7 | — | — | — |

| Pennsylvania | 15 | 14 | 1 | — | — |

| Delaware | 3 | 3 | — | — | — |

| Maryland | 8 | 8 | — | — | — |

| Virginia | 21 | — | 21 | — | — |

| North Carolina | 12 | — | 12 | — | — |

| South Carolina | 8 | 7 | — | — | 1 |

| Georgia | 4 | — | 4 | — | — |

| Kentucky | 4 | — | — | 4 | — |

| Total | 132 | 77 | 50 | 4 | 1 |

[Pg 7]

1796

While it was generally accepted that Washington would not be a candidate for a third term, he gave no definite expression on the subject until he issued his farewell address a short time before the election of 1796. Washington was an extremely reticent man, and it is possible that, in view of the serious complications between this country and France, he may have anticipated a contingency that would make him accept a third election to the Presidency, but it seems to have been well understood by those nearest to him in official circles that he earnestly desired to retire to private life at the expiration of his second term. He was then the richest man in the country, his wealth being almost wholly composed of land and slaves, and for twenty years he had been unable to give any attention to his large business interests. While his election and re-election to the Presidency by a unanimous vote were very gratifying to him, he greatly preferred the life upon his plantation, where he gave most careful attention to all the details of its management.

As early as 1793 it was generally accepted by the public that Washington would not be a candidate for re-election, and that Jefferson and Adams would be the logical competitors for the succession. Jefferson had cleared his decks for the battle by resigning his office as Secretary of State early in 1794. He was not in harmony with the severe Federal policy of Washington, and was very positively hostile to the policy of the administration in failing to support the French Revolution. Jefferson led the Democratic forces of the country; Washington, and Adams as his logical successor, led the Federal forces, and between them there was an irreconcilable dispute as to the form of government the new Republic should assume. Washington, Adams, Hamilton,[Pg 8] and their associates did not believe in the capacity of the people for self-government. They favored the strongest possible government, with checks and balances which could effectually restrain what they regarded as positive and dangerous ebullitions of public sentiment. They would have made Senators for life and given only the semblance of government to the people. Jefferson, on the other hand, took the broad ground that the people were sovereign and should rule. He logically supported the French Revolution against the Bourbon Kings, and cherished the strongest prejudices against England. As Secretary of State he could not well have remained in the Washington Cabinet the last two years of the administration, but he doubtless resigned to be entirely free to make his great battle for the Presidency in 1796.

Neither Jefferson nor Adams was nominated for the Presidency in 1796 by any Legislature or mass-meeting of which there is any record as far as I have been able to ascertain. Adams was the choice of Washington, and the logical successor to Washington as the Federal candidate for President, and Jefferson stood head and shoulders over all the Republicans of that day. The title of Republican was adopted by the friends of Jefferson, and the Democratic party was founded in 1796 by Jefferson under the name of Republican, established as the majority party of the nation four years later, and it fought and won the Democratic battles under that name until 1824, when the Jackson party changed the title to Democracy.

If the overshadowing individuality of Washington could have been eliminated from the contest of 1796, Jefferson would have defeated Adams by a decided majority, but Washington was earnestly enlisted in the support of Adams, and all the power of the administration was wielded in favor of the Federal candidate. While Washington was not charged with violent partisanship in his appointments, it is none the less true that when the issue came between Adams and Jefferson, every Federal official of the country felt bound to support, with all the power he possessed, the candidate preferred by Washington. Had Grover Cleveland lived in that day, he would have had ample opportunity to denounce the “pernicious activity” of office-holders with as much reason as he denounced them a century later in his support of civil service reform.

Not only were the Federal officials aggressively enlisted[Pg 9] in favor of Adams, but the personal influence of Washington, that was greater than that ever wielded by any other official or citizen of the Republic down to the present time, was a serious obstacle to Jefferson’s success. The people loved Jefferson as the author of the Declaration of Independence, and a large majority of them sympathized with his liberal ideas of popular government, but the name of Washington was sacred to a large majority, and his wishes were paramount in deciding their political action. Such were the conditions under which Jefferson entered the contest against Adams in 1796.

In this contest, for the first time, there were two candidates distinctly declared as competitors for the Presidency, and other candidates as distinctly declared as competitors for Vice-President, although all had to be voted for as candidates for President in the Electoral College. At that time Aaron Burr was in the zenith of his power. He was one of the most astute politicians of that day, inordinately ambitious, unscrupulous in his methods, and he was generally accepted by the friends of Jefferson as the candidate for Vice-President.

New York was a Federal State, but it was hoped that by the masterly ability of Burr the electoral vote of New York might be won for Jefferson, although while there was entire unanimity among the Republicans in support of Jefferson, there was not equal unanimity in the support of Burr. He failed to carry New York for Jefferson, but succeeded in carrying it for Jefferson and himself in 1800, and his victory was won so early in the contest by the election of a Republican Legislature in that State in May, 1800, that he practically decided the battle against Adams.

The Presidential contest between Jefferson and Adams developed into the most defamatory campaign ever known in the history of American politics, unless the second campaign of 1800 between the same leaders may be accepted as equalling it. In no modern national campaign have candidates and parties been so maliciously defamed as were candidates and parties when Jefferson and Adams fought for power in the contest of the Fathers of the Republic. Jefferson was denounced as an unscrupulous demagogue, and Adams was denounced as a kingly despot without sympathy with the people, and opposed to every principle of popular government.

[Pg 10]

There were few newspapers, but it was the age of the pamphleteer, and the political pamphlets of those days, if compared with the political asperities of the present age, would make the partisan vituperation of the evening of the nineteenth century appear as tame and feeble. Nor were political leaders of that day any less unscrupulous than are the political leaders of the present. The struggles of mean ambition were as common then as now, and political leaders jostled each other in the most vituperative assaults to give victory to their cause.

The contest ended in November, when the elections were held in the various States. Tennessee had been admitted to the Union on the 1st of June, 1796, making sixteen States to participate in the choice of a President. Of these, six States held some form of popular elections, while ten chose their electors by the Legislature. The popular vote cast at these elections had no material significance. There was but one ticket voted for in nearly or quite all of the six States which assumed to choose electors by popular vote, as the New England States were solid for Adams, and the Southern States, where elections were held, were strong in the support of Jefferson. The result was the election of Adams in the Electoral College by a vote of 71 to 68 for Jefferson, who thereby became Vice-President. The following is the vote in detail, as cast in the Electoral College, the electors voting only for President:

| STATES. | John Adams, Mass. | Thomas Jefferson, Va. | Thomas Pinckney, S. C. | Aaron Burr, N. Y. | Samuel Adams, Mass. | Oliver Ellsworth, Conn. | George Clinton, N. Y. | John Jay, N. Y. | James Iredell, N. C. | George Washington, Va. | Samuel Johnston, N. C. | John Henry, Md. | Charles C. Pinckney, S. C. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Hampshire | 6 | — | — | — | — | 6 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Vermont | 4 | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Massachusetts | 16 | — | 13 | — | — | 1 | — | — | — | — | 2 | — | — |

| Rhode Island | 4 | — | — | — | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Connecticut | 9 | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | 5 | — | — | — | — | — |

| New York | 12 | — | 12 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| New Jersey | 7 | — | 7 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Pennsylvania | 1 | 14 | 2 | 13 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Delaware | 3 | — | 3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | —[Pg 11] |

| Maryland | 7 | 4 | 4 | 3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | — |

| Virginia | 1 | 20 | 1 | 1 | 15 | — | 3 | — | — | 1 | — | — | — |

| North Carolina | 1 | 11 | 1 | 6 | — | — | — | — | 3 | 1 | — | — | 1 |

| South Carolina | — | 8 | 8 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Georgia | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Kentucky | — | 4 | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Tennessee | — | 3 | — | 3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Total | 71 | 68 | 59 | 30 | 15 | 11 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

It will be seen by the foregoing table that Pennsylvania,[2] Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina cast divided electoral votes for the Presidency between Jefferson and Adams. In Pennsylvania, Adams received 1 electoral vote to 14 for Jefferson. In Maryland, Adams received 7 to 4 for Jefferson. In Virginia, Jefferson’s own State, Adams received 1 to 20 for Jefferson, and in North Carolina the vote was 1 for Adams to 11 for Jefferson. In all of these States the electors were chosen by popular vote, and they were doubtless selected with reference to their character and intelligence without pledges as to how they should cast their ballots in the electoral colleges. One of the Virginia electors exercised his admitted right to vote against Jefferson, who had the largest popular following in the State. It was this independent action of a few electors in 1796 that made both parties draw their lines severely in the selection of the candidates for electors, and from that time until the present all electoral tickets have been made up of men who were accepted as solemnly pledged to vote for their party candidates in the Electoral College.

[Pg 12]

1800–1

The Presidential contest of 1800 was as revolutionary in its aim and in its accomplishment as was the Republican revolution of 1860. The Federalists had practically undisputed control of the Government for twelve years, under Washington and John Adams, and the power of the Federal party, with the overwhelming individuality of Washington in its favor, accomplished the election of Adams over Jefferson in 1796. When the battle of 1800 opened, Washington was dead, and Hamilton, one of the ablest of the Washington political lieutenants, was not in hearty sympathy with Adams.

The Federalists held both branches of Congress, and a tidal wave of partisan bitterness and personal defamation ran riot, both in Congress and throughout the country. Our foreign complications with France had become very serious, and Congress approved what was then regarded as very extensive preparations for a war that was bitterly opposed by the Republican minority, the followers of Jefferson. So violent were the political discussions of the country that Adams, acting in accord with the Federal theory of a strong suppressive government, demanded and secured the passage of what are known as the Alien and Sedition laws, which now rank among the most odious legislative acts in the history of the Republic.

While the Alien and Sedition laws were apparently aimed at those who were open enemies of the country in war, they were, in fact, intended to suppress criticism of the administration and to impose the severest penalties for open hostility to its policy. The first session of the Congress of 1797–98[Pg 13] lasted eight months, and even in the fierce passions of civil war the Congressional debates did not equal the asperities of the Congressional debates of a century ago. The first Alien law lengthened the period for naturalization to fourteen years, and all emigrants were required to be registered and the certificate of registration to be the only proof of residence. All alien enemies were forbidden the right of citizenship under any circumstances.

Another of the series gave the President the power in case of war to seize or expel all resident aliens of the nation at war with us, and yet another gave the President power to deport any alien whom he might think dangerous to the country, and if after being ordered away he remained in the country, he was subject to imprisonment for three years and forbidden citizenship. In addition to these provisions, aliens so imprisoned could be removed from the country by the President’s order. Such were the general provisions of the Alien law. The Sedition bill, that was part of the same policy, declared that any who hindered officers in the discharge of their duties or opposed any of the laws of the country were guilty of high crime and misdemeanor, punishable by fine and imprisonment. Those who were guilty of writing or publishing any false and malicious writings against Congress or the President, or aided therein, were made punishable by a fine of $2000 and imprisonment for two years.

These measures were in harmony with the Federal theory of government. The Federal leaders did not believe the people capable of self-government, and Adams felt justified in imposing the severest penalties upon all who severely criticised or violently opposed the administration. Washington was yet alive and in full mental and physical vigor when these laws were passed, and it is reasonable to assume that he approved of them, as he could have defeated them if he had opposed their enactment. Hamilton vainly protested against the Alien and Sedition laws as a fatal political blunder, but Federalism had never suffered defeat, and President Adams never doubted his re-election until the vote was declared against him.

The contest of 1800 had its lines so well defined from the outset that candidates for President and Vice-President were as clearly indicated, although without any formal declaration, as national tickets would be indicated by a national convention of modern times. There is no record[Pg 14] of the Congressional caucus in 1800, but it seems to be an accepted tradition that the Federals, who had a majority of the House, first called a secret caucus to confer about the management of the campaign. They did not formally name candidates, but by general consent Adams was accepted as the candidate for President and Charles C. Pinckney, of South Carolina, for Vice-President. Apparently well-authenticated reports tell of a Republican Congressional caucus held during the same year, but there is no preserved record of it. If such a caucus was held, candidates were not nominated nor was any declaration of principles made. The chief object of the Republican caucus seems to have been to harmonize the friends of Jefferson on Burr as the accepted candidate for Vice-President, but no preference was expressed in any formal way. When the Federalists held their first caucus the Republicans denounced it as a “Jacobinical conclave,” and so severe were the criticisms of the Philadelphia Aurora, the leading Jefferson organ, that its editor was at one time arraigned before the bar of the Senate.

The contest of 1800 opened early in the year, the reported Congressional caucuses having been held in February or March, and from that time until the election the political discussions were acrimonious to a degree that would surprise the present generation. Jefferson had cordially united his friends in the support of Burr, and it was Burr’s magnificent leadership that carried the electoral vote of New York by winning the Legislature of that State as early as May. New York had voted for Adams in 1796, and the loss to Adams of one of the leading States of the Union and its transfer to Jefferson made the battle next to hopeless for Adams, but he and his friends fought it out to the bitter end.

No new States had been admitted during the Adams administration, and the same sixteen States which had elected Adams over Jefferson were then to pass a second judgment upon the great leaders of the two opposing political theories of that day. In Pennsylvania the Federalists controlled the Senate chiefly by hold-over Senators, as the popular sentiment of the State was strongly for Jefferson. In the three previous elections for President the Pennsylvania Legislature had passed special acts authorizing a popular vote for President, but in 1800, the Federals having control of the Senate, refused to pass a bill for an election whereby the[Pg 15] choice of electors was thrown into the Legislature, and it required joint action of the Federal Senate and the largely Republican House to provide for a choice of electors even by the Legislature. The Federal Senators refused to go into joint convention except upon conditions which would divide the electoral vote, and the Republicans of the House were compelled to choose between disfranchising the State, as New York had been disfranchised in 1789, or to concede a large minority of the electors to Adams.

It was finally agreed that each House should nominate 8 electors, and that the Houses should then meet jointly and each member should vote together for 15 of the 16 thus nominated. The result was that the Federalists forced the election of 7 Adams electors with 8 for Jefferson. The Federal Senators, 13 in number, who controlled the Senate against the 11 Republicans, were heralded by their party papers and leaders as grand heroes, because by the accident of power in one body of the Legislature not immediately chosen by the people they had wrested 7 electors from Jefferson, which would have been given to him either by a popular vote or by a joint vote of the Legislature.

Rhode Island at this election for the first time chose electors by popular vote, making 6 States which chose electors by the vote of the people and 10 which chose electors by the Legislature. As the electoral colleges could vote only for candidates for President, Jefferson and Burr received precisely the same vote, 73 in number, and Adams received 65, with 64 for Pinckney and 1 for John Jay. The following is the table of the vote as cast in the electoral colleges:

| STATES. | Thomas Jefferson, Va. | Aaron Burr, N. Y. | John Adams, Mass. | C. C. Pinckney, S. C. | John Jay, N. Y. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Hampshire | — | — | 6 | 6 | — |

| Vermont | — | — | 4 | 4 | — |

| Massachusetts | — | — | 16 | 16 | — |

| Rhode Island | — | — | 4 | 3 | 1[Pg 16] |

| Connecticut | — | — | 9 | 9 | — |

| New York | 12 | 12 | — | — | — |

| New Jersey | — | — | 7 | 7 | — |

| Pennsylvania | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | — |

| Delaware | — | — | 3 | 3 | — |

| Maryland[3] | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | — |

| Virginia | 21 | 21 | — | — | — |

| North Carolina | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | — |

| South Carolina | 8 | 8 | — | — | — |

| Georgia | 4 | 4 | — | — | — |

| Kentucky | 4 | 4 | — | — | — |

| Tennessee | 3 | 3 | — | — | — |

| 73 | 73 | 65 | 64 | 1 |

It is impossible to give anything like an intelligent presentation of the popular vote between Jefferson and Adams. In most of the States which chose electors by popular vote there was practically no contest, as the New England States voted solidly for Adams, and the Southern States south of Maryland voted as solidly for Jefferson, with the exception of North Carolina, where an electoral ticket seems to have been chosen on the original theory that electors should exercise sound discretion in the choice of a President, and in the exercise of that discretion 4 of the North Carolina electors voted for Adams and 8 for Jefferson. Had Pennsylvania been permitted to give expression either to the popular will or to the decided Republican majority of the Legislature, 7 of the Pennsylvania votes would have been taken from Adams and added to Jefferson, which would have made him 80 electoral votes to 58 for Adams.

Jefferson had won his election, and there should have been no question about according it to him. Under the electoral system of that day, by which each elector voted for two candidates for President, Jefferson and Burr each received 73 votes for the Presidency, and upon the face of the returns[Pg 17] were equally entitled to claim the highest honor of the Republic. True, Burr had not been discussed or seriously thought of as a candidate for President. He was accepted by the Republicans distinctly as the candidate for Vice-President, and the whole battle was fought out on the issue between Jefferson and Adams. Had Burr been honest and manly, he would have ended the struggle at once by declaring that the people had elected Jefferson to the Presidency, and that Burr could not consent to be presented to the country and the world as seeking to wear the stolen honors of the Government; but Burr developed his true character as soon as he discovered that his vote was equal to that given to Jefferson. While he did not make any open or visible effort to elect himself over Jefferson, he silently assented to the use of his name, and thus made the Presidency hang in uncertainty from the time of the election in November until the 17th of February, when the contest was finally decided in favor of Jefferson, and Burr stamped with infamy. That he wished to be elected over Jefferson cannot be reasonably doubted. If he had not permitted the use of his name without protest as a candidate against Jefferson, there would have been no discussion and no uncertainty, as the House would have chosen Jefferson on the 1st ballot.

Jefferson could have accomplished his own election without a serious contest if he had accepted the proposition of the Federalists to give him the election, to which he was entitled by the vote of the people, if he would agree not to remove the Federalists who then filled all the offices of the Government. Under Washington and Adams, the Republicans were practically proscribed in national appointments, and Adams had been specially proscriptive in dispensing the patronage of his administration. One of the most discreditable acts of his administration was the creation, by his Federal Congress in the expiring hours of Federal rule, of a number of judges, to whom commissions were issued by Adams at midnight before his retirement from office. They were known in political discussions of that day as the “midnight judges,” and the measure was so odious that it speedily destroyed itself. Jefferson, while not specially proscriptive in political appointments, regarded it as inconsistent with his appreciation of executive duties to give any pledge to the opposition to retain their friends in office. They naturally assumed that Jefferson would be as proscriptive[Pg 18] as Adams had been, and that their only safety was in making terms with Jefferson, whose election they could accomplish without difficulty.

It is quite probable that they could have made such terms with Burr, and it is possible that such conditions were proposed and accepted, but the Federalists knew that the defeat of Jefferson would be a monstrous perversion of the popular will; and Hamilton and Bayard, of Delaware, and other prominent Federalists earnestly opposed all affiliation with Burr. Burr having failed to announce that Jefferson had been elected President by the people, and should be elected by the House, and Jefferson having refused to make terms with the Federalists, the election went into the House under rules which had been adopted by Congress to meet the special case. Under the rules, the House was required to retire to its own chamber after the announcement of the electoral vote showing no choice, and proceed to ballot for President, and to continue to ballot without adjournment until a choice was effected. That session of the House continued for seven days. The balloting began on the 11th of February and ended on the 17th, as the House, instead of adjourning, simply took recesses from time to time. Each State could cast but one vote in the House, and that vote was determined by a majority of the delegation. Where the delegation was evenly divided the State had no vote. The following is the vote of the States on the 1st ballot, February 11, 1801:

| STATES. | Jefferson. | Burr. | State voted for. |

|---|---|---|---|

| New Hampshire | — | 4 | Burr. |

| Vermont | 1 | 1 | Divided—Blank. |

| Massachusetts | 3 | 11 | Burr. |

| Rhode Island | — | 2 | Burr. |

| Connecticut | — | 7 | Burr. |

| New York | 6 | 4 | Jefferson. |

| New Jersey | 3 | 2 | Jefferson. |

| Pennsylvania | 9 | 4 | Jefferson. |

| Delaware | — | 1 | Burr. |

| Maryland | 4 | 4 | Divided—Blank. |

| Virginia | 16 | 3 | Jefferson. |

| North Carolina | 9 | 1 | Jefferson. |

| South Carolina | — | 5 | Burr. |

| Georgia | 1 | — | Jefferson. |

| Kentucky | 2 | — | Jefferson. |

| Tennessee | 1 | — | Jefferson. |

| Total | 55 | 49 |

[Pg 19]

Nineteen ballots were taken on the same day, then a recess was taken until the 12th, when 9 additional ballots were taken, and 1 ballot was taken on the 13th, 4 on the 14th, 1 on the 16th (the 15th being Sunday), and 1 on the 17th, making an aggregate of 35 ballots, all of which were precisely a repetition of the 1st ballot given in the foregoing table. Jefferson received the vote of 8 States, Burr of 6, and 2 were blank, because of divided delegations. The vote of 9 States was necessary to an election, and there was no choice.

On the 2d ballot cast on the 17th, being the 36th ballot in all, Jefferson was successful, receiving the votes of 10 States to 4 for Burr and 2 blank. The changes in favor of Jefferson were made by one Vermont member declining to vote, thus allowing his colleague to cast the vote of the State for President, and by four from Maryland also declining to vote, by which the tie in that State was broken in Jefferson’s favor.

In addition to these changes South Carolina and Delaware cast blank votes, but they did not help Jefferson, as he required the positive vote of 9 States to accomplish his election. It was James A. Bayard, of Delaware, a leading Federalist, who changed his vote on the last ballot from a vote for Burr to a blank ballot. Jefferson was thus declared elected President, and Burr became Vice-President by the mandate of the Constitution, he having received the highest electoral vote for President excepting that cast for Jefferson.

It can be readily understood that Burr’s permission of the use of his name to defeat the election of Jefferson in the House made an impassable gulf between them, and that contest dated the decline of Burr’s power in the land. He knew that there could be no future for him, and his restless genius sought new fields in which to gratify his ambition, ending in his arrest and trial for treason, and also staining his skirts with the murder of Hamilton. Hamilton was open in his hostility to Burr in the contest between Jefferson and Burr in the House, and it was Burr’s resentment of Hamilton’s hostility to his election that made him seize upon a trivial pretext to force Hamilton into a duel, in which Hamilton fell mortally wounded at the first fire. Burr’s public career was thus ended by the Jefferson-Burr contest, and although he lived many years thereafter, he drank the[Pg 20] bitterest dregs of sorrow, and died in poverty and unlamented.

Adams accepted his defeat most ungracefully. He remained in the Executive Mansion until midnight of the 3d of March, 1801, when he and his family deserted it, leaving it vacant for Jefferson to enter, without a host to welcome him. It was the only instance in which the retiring President did not personally receive the incoming President in the Executive Mansion, with the single exception of President Johnson, who did not remain at the White House to receive Grant; but Johnson was excusable from the fact that Grant had expressed his purpose not to permit Johnson to accompany him in the inauguration ceremonies. Jefferson, in marked contrast with the pomp and ceremony of Federal inaugurations, appeared on the 4th of March clad in home-spun, and rode his own horse unattended to the Capitol, and after the inauguration ceremonies returned to the Executive Mansion in like manner. Both Jefferson and Adams lived for more than a quarter of a century after their great battle terminated in 1800, and time greatly mellowed the asperities of their desperate political conflicts. In the later years of their life, when both had lived long in retirement, they had friendly correspondence; and it is one of the most notable events in our political annals that Jefferson and Adams, who stood side by side in presenting the Declaration of Independence to Congress, and who had fought the fiercest political battles of the nation as opposing leaders, both died on the same day—the natal day of the Republic—July 4, 1826.

[Pg 21]

1804

The election of Jefferson in 1800 was a complete revolution in the political policy of the new Republic, and it maintained its supremacy for sixty years. The Republican party that triumphed with Jefferson never suffered a defeat until after the name of the party had been changed to Democracy under Jackson. John Quincy Adams, who was elected President in 1824, was nominated and supported as a Republican, as were Jackson, Crawford, and Clay, and the Whig triumphs of 1840 and 1848 stand in our history as accidental victories without changing the general policy of the Government in any material respect. It may be accepted as a fact that from 1800 until 1900, the full period of a century, there have been but two political policies established and maintained in the government of this country. The Democratic policy ruled from 1800 to 1860, and from 1860 to 1900 the Republican policy has maintained its supremacy, notwithstanding the two Democratic administrations of Cleveland. They were but temporary checks upon Republican mastery, as the Whig successes of 1840 and 1848 were mere temporary checks upon Democratic rule.

With Jefferson’s success in 1800 came, for the first time, the control of the Republicans in both branches of Congress, and Jefferson thus had the entire legislative power of the Government in thorough sympathy and harmony with himself. He was bitterly opposed by the Federalists at every step. They justly criticised his hostility to an American navy; they complained vehemently of his removals from office in partisan interests, and they specially assailed his ostentatious attempts to limit the authority and powers of the General Government to give the supreme sovereignty of the nation to the people.

[Pg 22]

The one act of his administration that was most violently assailed was his purchase of Louisiana in 1803. It was proclaimed by the Federalists as the most flagrant usurpation of authority, as an utter overthrow of the Constitution, and as the beginning of the end of the Union. There is not an argument made to-day against the acquisition of the Philippines and Puerto Rico that is not the echo of the earnest arguments made by the Federalists against the acquisition of Louisiana. The ablest of the Federalists proclaimed in the Senate and House that the Union was practically destroyed by the acquisition of a distant country, containing a people with no sympathy with our interests or institutions; who were generally strangers to our language and could never be educated to the proper standard of American citizenship. But the country then, as now, believed in expansion, and the acquisition of Louisiana stands out as one of the grandest achievements of statesmanship exhibited by any administration, from Washington to McKinley.

The contest between Jefferson and Burr for the Presidency, after one had been distinctly supported as a candidate for President and the other as distinctly as a candidate for Vice-President, taught the necessity of changing the method of choosing a President in the Electoral College, but the Federalists bitterly opposed the change, chiefly on the ground that it was desired solely to gratify the personal ambition and interests of Jefferson. The proposed amendment prevailed, however, and was ratified by thirteen of the sixteen States in ample time for the contest of 1804. The dissenting States in the ratification of the amendment were Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Delaware. Under that amendment the electors voted for President and Vice-President as they do to-day, and the candidate for Vice-President must now have a majority of the electoral vote as well as the candidate for President to be successful.

The Congressional caucus that made Presidents for many years became an accepted institution in 1804, when the Republican or Jeffersonian members of Congress were publicly invited to meet on the 25th of February. They unanimously nominated Mr. Jefferson for re-election, and as Burr was unthought of for Vice-President, they nominated George Clinton, of New York, for that office. This was the first open political caucus or convention to nominate national candidates. The caucuses of 1800 were held in secret by both[Pg 23] the Federalists and Republicans, and no record was preserved of their actions. Those who called the caucus, appreciating the prejudice that would likely be provoked by Congress attempting to dictate the candidates for President and Vice-President, distinctly declared that the caucus or conference was called solely as individuals, and not as official representatives of the Senate and House. If the Federalists held a caucus in 1804, there is no record of it that I have been able to find, but they united on Charles C. Pinckney, of South Carolina, for President, and Rufus King, of New York, for Vice-President. Both of the parties gave the second place on their respective tickets to New York, clearly indicating that they regarded New York as one of the pivotal States of the conflict.

Ohio had been admitted into the Union in 1802, making 17 States to take part in the election of 1804, and the new apportionment, shaped by the census of 1800, enlarged the number of electoral votes. While the Federalists had greatly diminished in popular strength by the loss of power and the steadily gaining approval of Jefferson and his Republican policy, they did not abate in any degree the intensity of their hostility to Jefferson, and in a few States where contests were made, the campaigns were conducted on the old defamatory lines which marked the two great battles between Jefferson and Adams.

In most of the States there was practically no contest, but in Massachusetts and Connecticut, where Federalism had always maintained its supremacy, the Federalists fought with an earnestness and desperation such as might have been expected in a hopeful struggle. The fiercest battle was fought in Massachusetts, where for the first time the Republicans defeated the Federalists in the largest vote ever cast in the State. Jefferson electors received 29,310 votes to 25,777 for the Pinckney ticket, giving Jefferson a majority of 3533. This was a terrible blow to Adams, and it was aggravated by the fact that while Massachusetts faltered, Connecticut gave her electoral vote to the Federal ticket. Delaware, with her three electoral votes, was the only other State that maintained her devotion to the Federal cause, and the electoral votes of those 2 States, with 2 added from the 11 votes of Maryland, summed up the entire vote of the Federal candidate for President in the Electoral College, the vote being 162 for Jefferson to 14 for Pinckney, and a like vote[Pg 24] for Clinton and King for Vice-President. The following table presents the official vote cast in the electoral colleges:

| STATES. | President. | Vice-President. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas Jefferson. | Charles C. Pinckney. | George Clinton. | Rufus King. | |

| New Hampshire | 7 | — | 7 | — |

| Vermont | 6 | — | 6 | — |

| Massachusetts | 19 | — | 19 | — |

| Rhode Island | 4 | — | 4 | — |

| Connecticut | — | 9 | — | 9 |

| New York | 19 | — | 19 | — |

| New Jersey | 8 | — | 8 | — |

| Pennsylvania | 20 | — | 20 | — |

| Delaware | — | 3 | — | 3 |

| Maryland | 9 | 2 | 9 | 2 |

| Virginia | 24 | — | 24 | — |

| North Carolina | 14 | — | 14 | — |

| South Carolina | 10 | — | 10 | — |

| Georgia | 6 | — | 6 | — |

| Kentucky | 8 | — | 8 | — |

| Tennessee | 5 | — | 5 | — |

| Ohio | 3 | — | 3 | — |

| Total | 162 | 14 | 162 | 14 |

[Pg 25]

1808–12

The election of Jefferson ended the line of the succession to the Presidency from the Vice-Presidency. Adams as Vice-President succeeded Washington as President, and Jefferson as Vice-President succeeded Adams, but the Burr fiasco made it impossible for the succession to be maintained, and for many years the line of succession to the Presidency was in the Premiers of the administration. Indeed during the entire century from 1800 to 1900 but one Vice-President has been elected to the Presidency. That single exception was Martin Van Buren, and he started under the Jackson administration as Premier. Madison, who was Secretary of State under Jefferson, succeeded Jefferson to the Presidency; Monroe, Secretary of State under Madison, succeeded Madison as President; John Quincy Adams, Secretary of State under Monroe, succeeded Monroe as President, and since that time Buchanan was the only Secretary of State who reached the Presidency, although Webster, Cass and Blaine, who were Premiers under several administrations, were defeated in Presidential contests.

Madison was generally regarded as the favorite of Jefferson for the succession, and Jefferson’s power at that time was second only to the power of Washington in dictating who should succeed him to the highest honor of the Republic. Irritating opposition to Madison came from his own State of Virginia, where the friends of Monroe were quite aggressive. Two caucuses had been held in the Virginia Legislature, one by the friends of Madison, and the other, much smaller in number, by the friends of Monroe, and both were thus formally presented to the country to succeed Jefferson.

A caucus of the Republican members of both branches of[Pg 26] Congress was called to meet on the 23d of January, 1808. It was known that the friends of Madison largely outnumbered the friends of Monroe in Congress, and the active supporters of Monroe earnestly opposed a nomination by the Congressional caucus. The caucus was held, however, and was attended by a majority of the Senators and Representatives, and Madison was nominated on the 1st ballot, receiving 83 votes to 3 for Monroe and 3 for George Clinton. Monroe had a considerably larger strength in Congress, but the result was predetermined, and a number of them did not participate. George Clinton was nominated by substantially the same vote for Vice-President. The caucus system was under fire, and the caucus, in justification of its own act, adopted a resolution declaring that in making the nominations the members had “acted only in their individual characters as citizens,” and because it was “the most practical mode of consulting and respecting the interests and wishes of all upon a subject so truly interesting to the people of the United States.”

It was a considerable time before the friends of Monroe gave a cordial adhesion to the caucus nominations, but Jefferson, who was friendly to both Madison and Monroe, interposed and reconciled the friends of Monroe by the expectation that Monroe would succeed Madison; and as there was practically no serious opposition to Madison presented by the Federalists, the campaign drifted into the general acceptance of Madison’s election long before the election was held. The Federalists did not hold any caucus or formally present candidates, but accepted Pinckney and King, for whom they had voted in the last contest against Jefferson.

In the New England States vigorous contests were made by the Federalists to regain the supremacy they had lost, and New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Rhode Island, which had voted for Jefferson, were regained by the Federalists, but the struggle was not made with any hope of defeating Madison for President. There had been no increase in the number of States nor in the vote of the electoral colleges. Madison won an easy and decisive victory, receiving 122 electoral votes to 47 for Pinckney and 6 for George Clinton, who was the regular nominee of the Republicans for Vice-President, and who was elected to that office by 113 electoral votes to 47 for King and 15 scattering. New York was obviously disaffected, as while the Republican caucus had accorded[Pg 27] to Clinton of that State the second place on the ticket, and elected him Vice-President, the electoral vote of New York was divided, Madison receiving 13 to 6 cast for Clinton, and in the same electoral college Clinton received 13 votes for Vice-President to 3 for Madison and 3 for Monroe. The votes of North Carolina and Maryland were also divided, but that was not unusual, as after Washington retired the electoral votes of those States were divided, because their electors were chosen by Congressional districts.

There is no intelligent record of the popular vote, and it would be needless to attempt to present it, as outside of New England the States which were contested generally chose their electors by the Legislature. The following is the vote in detail as cast in the Electoral College:

| STATES. | President. | Vice-President. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| James Madison, Va. | George Clinton, N. Y. | C. C. Pinckney, S. C. | George Clinton, N. Y. | James Madison, Va. | John Langdon, N. H. | James Monroe, Va. | Rufus King, N. Y. | |

| New Hampshire | — | — | 7 | — | — | — | — | 7 |

| Vermont | 6 | — | — | — | — | 6 | — | — |

| Massachusetts | — | — | 19 | — | — | — | — | 19 |

| Rhode Island | — | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | 4 |

| Connecticut | — | — | 9 | — | — | — | — | 9 |

| New York | 13 | 6 | — | 13 | 3 | — | 3 | — |

| New Jersey | 8 | — | — | 8 | — | — | — | — |

| Pennsylvania | 20 | — | — | 20 | — | — | — | — |

| Delaware | — | — | 3 | — | — | — | — | 3 |

| Maryland | 9 | — | 2 | 9 | — | — | — | 2 |

| Virginia | 24 | — | — | 24 | — | — | — | — |

| North Carolina | 11 | — | 3 | 11 | — | — | — | 3 |

| South Carolina | 10 | — | — | 10 | — | — | — | — |

| Georgia | 6 | — | — | 6 | — | — | — | — |

| Kentucky[4] | 7 | — | — | 7 | — | — | — | — |

| Tennessee | 5 | — | — | 5 | — | — | — | — |

| Ohio | 3 | — | — | — | — | 3 | — | — |

| 122 | 6 | 47 | 113 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 47 | |

[Pg 28]

The battle for Madison’s second election in 1812 began in the early period of our second war with Great Britain. Many complicated foreign questions excited earnest discussion and renewed the partisan bitterness of the earlier national contests, while the struggle for the renewal of the charter of the United States bank convulsed financial and business circles. The bill was lost by indefinite postponement in the House in 1811 by a single vote, and soon thereafter a like bill was rejected in the Senate by the casting vote of the Vice-President. Madison did not possess the breadth of statesmanship so grandly exhibited by Jefferson, and he lacked in the positive qualities needed to meet the grave issues which confronted him. He parried our foreign questions with almost endless diplomatic correspondence, and in the conduct of the war he lacked in the settled purpose and methods which are always necessary to sustain a government in such a crisis.

It was then that Clay came to the front as Commoner of the nation, and it was his able, eloquent, and inspiring utterances and actions, aided by Senator Crawford, of Georgia, that saved the administration when it was apparently threatened with defeat. Madison was unwilling to accept war with England until it became clearly evident that he must declare war or give the Federalists a restoration to power, and it was only after he had been very earnestly appealed to by the men upon whom he had most to depend, that he sent a message to Congress pointing out the necessity of a declaration of war, to which both branches in secret sessions gave their approval.

It was not until after Madison had decided upon an aggressive war policy with England that the Congressional caucus was called to nominate Republican candidates for President and Vice-President. The caucus met on the 12th of May apparently without objection, and Madison was renominated by a unanimous vote, only one member present declining to vote. Clinton had died in office, and a new nomination had to be made for Vice-President. John Langdon, of New Hampshire, who was the first Senator to be President pro tem. of the body, was nominated for Vice-President, receiving 64 votes to 16 for Elbridge Gerry and 2 scattering. Langdon declined the nomination, and the second caucus was convened when Gerry was nominated by a vote of 74 to 3 scattering. While the proceedings of the caucus[Pg 29] were apparently very harmonious, there was significance in the fact that some 50 Republican Senators and Representatives did not attend, only one being present from New York State.

The reason for the New York members declining to attend the caucus was soon developed by a counter movement, made in New York, to bring out DeWitt Clinton, who was the leader of the Republicans of that State, as the candidate in opposition to Madison. The Federalists had no part in making him the competitor of Madison, but they were quite willing, in their utter helplessness, to support any bolt against the omnipotence of the Republican caucus. Many of the Republicans thought that the administration was not sufficiently aggressive in its opposition to England, and many others opposed Madison and were ready to support Clinton or any other promising candidate who was entirely opposed to the war. Had Clinton acted in harmony with the Republicans and supported Madison, he would have been a very formidable competitor of Monroe for the succession, but in allowing himself to be made a candidate of the opposition, he entirely lost his position as a Republican leader.

Madison had been nominated by the Republican Congressional caucus on the 12th of May, and on the 29th of May a caucus of the Republican members of the New York Legislature was held, at which 91 of the 93 members were present, and they unanimously nominated Clinton as a candidate for President, and the Federalists gradually dropped into his support. The Federalists took no formal action for the selection of candidates until September, when a conference of the leaders of that party was held in New York, with representatives from 11 States, and that conference nominated Clinton for President with Jared Ingersoll for Vice-President.

The campaign logically drifted into a square issue between the war and the peace parties, and even with all the factional hostility to Madison in the Republican ranks, such an issue could result only in the success of the party that sustained the Government in its war with England. The Federalists carried a solid New England vote for Clinton with the exception of Vermont, that broke loose from her Federal moorings and cast her entire electoral vote for Madison. New York, with the largest electoral vote of any State, was carried chiefly by Clinton’s personal popularity, and New Jersey was lost to Madison in disregard of the popular vote of[Pg 30] the State by a Federal Senate and House that was successful against a Republican majority by reason of the peculiar shaping of the legislative districts. The Legislature repealed the law for the choice of electors by a popular vote, and elected Federal electors by the Legislature. Had the popular vote of New Jersey prevailed, the vote between Madison and Clinton in the Electoral College would have been 136 for Madison to 81 for Clinton. The following is the vote as cast by the electoral colleges:

| STATES. | President. | Vice-President. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| James Madison, Va. | DeWitt Clinton, N. Y. | Elbridge Gerry, Mass. | Jared Ingersoll, Penn. | |

| New Hampshire | — | 8 | 1 | 7 |

| Vermont | 8 | — | 8 | — |

| Massachusetts | — | 22 | 2 | 20 |

| Rhode Island | — | 4 | — | 4 |

| Connecticut | — | 9 | — | 9 |

| New York | — | 29 | — | 29 |

| New Jersey | — | 8 | — | 8 |

| Pennsylvania | 25 | — | 25 | — |

| Delaware | — | 4 | — | 4 |

| Maryland | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 |

| Virginia | 25 | — | 25 | — |

| North Carolina | 15 | — | 15 | — |

| South Carolina | 11 | — | 11 | — |

| Georgia | 8 | — | 8 | — |

| Kentucky | 12 | — | 12 | — |

| Tennessee | 8 | — | 8 | — |

| Louisiana | 3 | — | 3 | — |

| Ohio | 7 | — | 7 | — |

| Total | 128 | 89 | 131 | 86 |

Louisiana was admitted into the Union on the 8th of April, 1812, and participated in the Presidential election, making 18 States. It will be seen that there was but one State that cast a divided electoral vote. Maryland continued[Pg 31] to choose all but the electors at large by Congressional districts, and gave 6 votes to Madison and 5 to Clinton. North Carolina changed her method of electing by districts to the choice of electors by the Legislature, thus making her electoral vote solid. Gerry, the candidate for Vice-President on the ticket with Madison, received 3 more votes in the Electoral College than were given to Madison, one of which came from New Hampshire and two from Massachusetts.

[Pg 32]

1816–20

The election of James Monroe to the Presidency in 1816 and his re-election in 1820 did not rise to the dignity of political contests. The Federal party was practically overthrown by the success of the war with England, and after the close of the war Federalism never asserted itself as a political factor in national affairs. There were murmurings of discontent in the Republican organization, but the Federalists were then in the unenviable attitude of having sympathized with the enemy in a foreign war, and the prejudices of the patriotic people of the country were intensified against the action of the Hartford convention, for which the Federalists were held responsible.

Whether justly or unjustly, it was believed by the Republicans throughout the country that the Hartford conventionists had given “blue-light” signals to the enemy’s ships, and thereby hindered the escape of American vessels which were blockaded. The overthrow of Federalism was so complete that the party never again formally presented candidates for President and Vice-President, and the first Monroe election of 1816 would probably have been as unanimous in the Electoral College as was his second election but for the fact that the three Federal States which voted against Monroe did not hold popular elections for President at all, but chose their electors by the Legislature. Massachusetts, the home of Adams, that had always chosen Presidential electors by popular vote, repealed the law in 1816, so that there was not a single elector chosen by the people against Monroe.

While Monroe’s two elections and administrations are now pointed to as the “era of good feeling,” that has never been repeated in this country. Monroe himself did not[Pg 33] reach the Presidency by the rosy path that would now be naturally accepted for him in his journey to the highest civil trust of the nation. The usual Congressional caucus was called on the 10th of March, 1816, asking the Republican Senators and Representatives to meet on the 12th for the purpose of nominating candidates for President and Vice-President. Only 58 of the 141 Republican members attended this meeting, and, instead of taking action, a resolution was passed calling a general caucus for the 16th, and at that caucus 118 members appeared. There were strong and widespread prejudices against the Congressional caucus system, and it was denounced by many prominent Republicans as “King Caucus” that sought to control the people in the selection of the highest officers.

Senator Crawford, of Georgia, who had been the leading Senator, as Clay was the leading Representative, in the support of the war during the Madison administration, was an aggressive candidate for President, and was more popular with the politicians generally throughout the country than was Monroe. Great anxiety was felt about the probable action of the caucus, as it was feared that Monroe might be overthrown, notwithstanding the fact that he was favored by both Jefferson and Madison. When the caucus met with twenty-three Republican absentees, the majority of whom absented themselves because they were positively opposed to the caucus system, Mr. Clay offered a resolution declaring it inexpedient to nominate candidates, but his proposition failed. He thus put himself on record as early as 1816 against the caucus system, and he rejected and took the field against it as a candidate in 1824.

The canvass between Monroe and Crawford was very animated, and Monroe succeeded by only 11 majority, the vote being 65 for Monroe and 54 for Crawford. Governor Daniel D. Tompkins, of New York, was nominated for Vice-President, receiving 20 votes more than were given to Monroe. The Crawford sentiment was strong in New York and New Jersey, as well as in North Carolina, Kentucky, and his native State of Georgia, and public meetings were held in different sections of the country after the nominations had been made, denouncing the caucus system, at one of which Roger B. Taney, who later became Chief Justice, was one of the aggressive opponents.

Had there been a formidable Federal party, it is doubtful[Pg 34] whether Monroe’s election might not have been seriously imperilled, but the war feeling was too fresh in the minds of the people to tolerate anything that was in sympathy with that expiring political organization. The Republicans who were opposed to Monroe had to choose between falling in with the caucus nomination, and giving Monroe a unanimous support, or making a square fight as a bolting Republican faction, without permitting the aid of the Federalists. As that was impracticable, the Republican discontent gradually subsided and the election of Monroe was conceded by all.

The Federalists made no nomination, but supported Rufus King, one of their old national candidates, and scattered their few votes for Vice-President, no two of the three States voting for the same candidate. Indiana had adopted a State Constitution in June, but was not formally admitted to the Union until the 11th of December, after the Presidential election had been held. The State, however, had voted for President, and elected three Republican electors for Monroe, but an animated dispute arose in Congress about counting the vote, because of the alleged ineligibility of Indiana to vote for President when not formally admitted into the Union, even though the people had adopted a State Constitution several months before the election. The two bodies separated, to enable the House to decide the issue, but finally the question was postponed by a nearly unanimous vote, and the Senate invited to return, when the vote was declared as follows:

| STATES. | President. | Vice-President. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| James Monroe, Va. | Rufus King, N. Y. | Daniel D. Tompkins, N. Y. | John E. Howard, Md. | James Ross, Penn. | John Marshall, Va. | Robert G. Harper, Md. | |

| New Hampshire | 8 | — | 8 | — | — | — | — |

| Vermont | 8 | — | 8 | — | — | — | — |

| Massachusetts | — | 22 | — | 22 | — | — | — |

| Rhode Island | 4 | — | 4 | — | — | 4 | —[Pg 35] |

| Connecticut | — | 9 | — | — | 5 | — | — |

| New York | 29 | — | 29 | — | — | — | — |

| New Jersey | 8 | — | 8 | — | — | — | — |

| Pennsylvania | 25 | — | 25 | — | — | — | — |

| Delaware | — | 3 | — | — | — | — | 3 |

| Maryland | 8 | — | 8 | — | — | — | — |

| Virginia | 25 | — | 25 | — | — | — | — |

| North Carolina | 15 | — | 15 | — | — | — | — |

| South Carolina | 11 | — | 11 | — | — | — | — |

| Georgia | 8 | — | 8 | — | — | — | — |

| Kentucky | 12 | — | 12 | — | — | — | — |

| Tennessee | 8 | — | 8 | — | — | — | — |

| Louisiana | 3 | — | 3 | — | — | — | — |

| Ohio | 8 | — | 8 | — | — | — | — |

| Indiana | 3 | — | 3 | — | — | — | — |

| Total | 183 | 34 | 183 | 22 | 5 | 4 | 3 |