*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 75040 ***

Footnotes have been collected at the end of each chapter, and are

linked for ease of reference.

There are numerous illustrations, which are represented here, which

have been moved slightly to fall in between paragraphs or sections.

Minor errors, attributable to the printer, have been corrected. Please

see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text

for details regarding the handling of any textual issues encountered

during its preparation.

Any corrections are indicated using an underline

highlight. Placing the cursor over the correction will produce the

original text in a small popup.

Any corrections are indicated as hyperlinks, which will navigate the

reader to the corresponding entry in the corrections table in the

note at the end of the text.

I

II

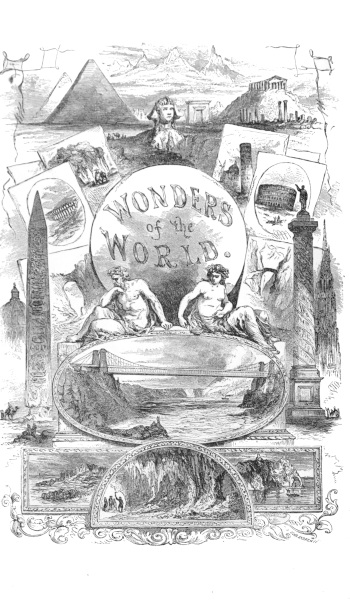

THE

WONDERS OF THE WORLD:

A

COMPLETE MUSEUM, DESCRIPTIVE AND PICTORIAL,

OF THE

WONDERFUL PHENOMENA AND RESULTS

OF

NATURE, SCIENCE AND ART.

ILLUSTRATED FROM ORIGINAL DESIGNS BY BILLINGS AND OTHERS.

Hartford:

PUBLISHED BY CASE, TIFFANY AND COMPANY.

1856.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1855, by

CASE, TIFFANY AND COMPANY,

in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of Connecticut.

3

PREFACE.

The ancients boasted of their SEVEN WONDERS OF THE WORLD. These were

the Pyramids of Egypt, the Colossus of Rhodes, the Aqueducts of Rome,

the Labyrinth on the banks of the Nile, the Pharos of Alexandria, the Walls

of Babylon, and the temple of Diana at Ephesus. But the WONDERS known

to those of the present day, may be counted by hundreds: wonders of

Nature, wonders of Science, wonders of Art, and Miscellaneous wonders;

each department full, to overflowing, of themes of the richest instruction

and deepest interest.

To present some of the most striking of these wonders, in a manner that

shall be acceptable to the man of science and profound research, and at the

same time full of interest to the general reader, and the family at the fireside,

has been the aim of the editor of the following pages. The exaggerated

and marvelous stories which the mischievous fancy of travelers has

too often imposed on the credulity of the weak, as well as the foolish fables

founded in bigotry and superstition, which were too often received as truths

in the dark ages, have been carefully avoided, and, where the narrative permitted,

exposed; and nothing has been brought forward that has not been

confirmed by the concurrent testimony of enlightened travelers, and men

of science, and extended observation. On the subjects in which Nature, in

her various departments, displays her most wondrous magnificence and

beauty; or in those in which Science and Art have sought out their most

4wondrous inventions, and wrought out the most wondrous results, the best

authorities have been carefully consulted. And the endeavor has been, so

to assemble and arrange the multiplied objects of wonder and delight, as to

confer a lasting benefit on the rising generation, and on families, and at the

same time to present a work that shall commend itself to those whose lives

have been wholly devoted to researches among the sublime wonders of

nature, science and art. Believing that the standard of general reading is

constantly rising higher, and that the sphere of intellectual tastes and pursuits

is constantly growing wider, the writer has endeavored to prepare a

volume that shall have more than the interest of fiction, and, at the same

time, the ripe and rich instruction of the book of travels, or the work of

science or descriptive art. The table of contents makes manifest how

extensive the range of the topics presented; while the list of engravings

may show how profusely and richly the enterprise of the publishers has

illustrated a work, which it is hoped may meet with universal acceptance.

J. L. A.

5

CONTENTS.

| |

PAGE. |

| Preface |

3 |

| List of Illustrations |

8 |

| |

|

| MOUNTAINS. |

| The Andes |

9 |

| Chimborazo |

12 |

| Cotopaxi |

13 |

| Pichincha |

14 |

| Mount Etna |

15 |

| Mount Vesuvius |

21 |

| Mount Hecla |

28 |

| The Geysers |

32 |

| The Sulphur Mountain (Iceland) |

36 |

| Mont Blanc |

37 |

| The Glaciers, or Ice Masses |

51 |

| The Mer de Glace |

51 |

| View from the Buet |

55 |

| Montserrat |

57 |

| The Peak of Teneriffe |

59 |

| The Souffriere Mountain, (St. Vincent, W. I.) |

69 |

| Peter Botte’s Mountain, (Mauritius) |

73 |

| Kilauea, (Sandwich Islands) |

74 |

| The Peak of Derbyshire |

82 |

| Mountains of Great Britain |

97 |

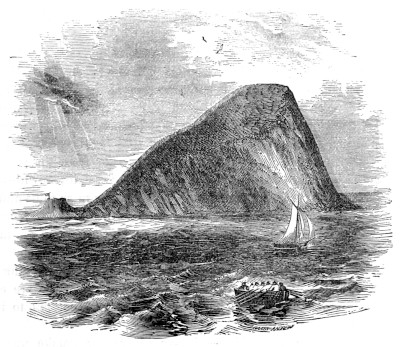

| Stromboli |

101 |

| Lipari |

103 |

| Vulcano |

104 |

| The Himalaya Mountains |

105 |

| Asiatic Volcanoes |

115 |

| Islands which have risen from the Sea |

119 |

| |

|

| SUBTERRANEAN WONDERS. |

| The Grotta del Cane |

131 |

| The Grotto of Antiparos |

136 |

| Caverns in Hungary and Germany, containing Fossil Bones |

139 |

| The Mammoth Cave |

141 |

| The Great Cavern of Guacharo |

157 |

| Fingal’s Cave, or Grand Staffa Cavern |

161 |

| Other Grottos and Caverns |

164 |

| |

|

| MINES, METALS, GEMS, &C. |

| Introductory |

168 |

| Diamond Mines |

169 |

| Gold and Silver Mines |

178 |

| Quicksilver Mines |

193 |

| Iron Mines |

195 |

| Copper Mines |

204 |

| Tin Mines |

209 |

| Lead Mines |

211 |

| Coal Mines |

212 |

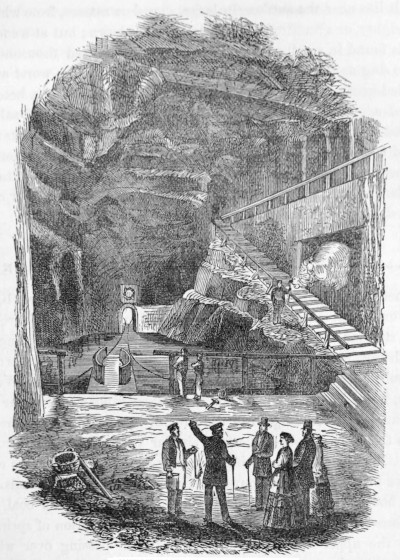

| Salt Mines |

223 |

| |

|

| PHENOMENA OF THE OCEAN. |

| Introductory |

230 |

| Saltness of the Sea |

231 |

| Congelation of Sea-Water |

234 |

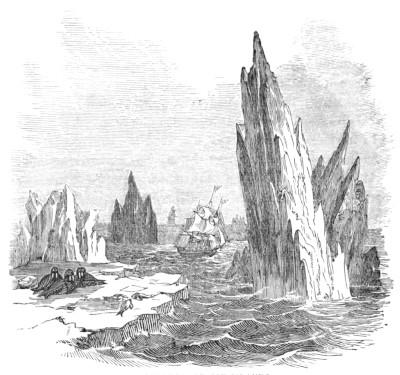

| Ice-Islands |

235 |

| Icebergs |

244 |

| Luminous Points in the Sea |

245 |

| Tides and Currents |

246 |

| |

|

| CATARACTS AND CASCADES. |

| Introductory |

252 |

| Falls of Niagara |

253 |

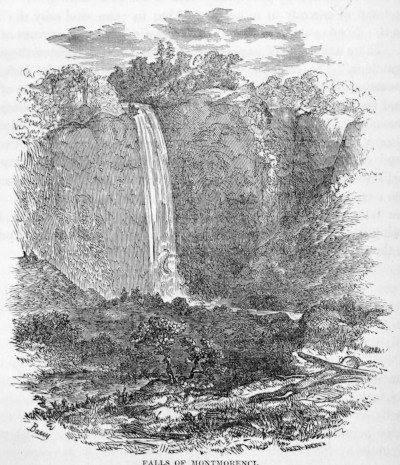

| Falls of the Montmorenci |

270 |

| The Tuccoa Fall |

272 |

| Falls of the Missouri |

272 |

| Catskill Falls |

274 |

| Trenton Falls |

275 |

| Waterfall of South Africa |

275 |

| Cataracts of the Nile |

276 |

| Cataract of the Mender |

276 |

| Other Cataracts |

277 |

| |

|

| SPRINGS AND WELLS. |

| St. Winifred’s Well |

280 |

| Wigan Well |

282 |

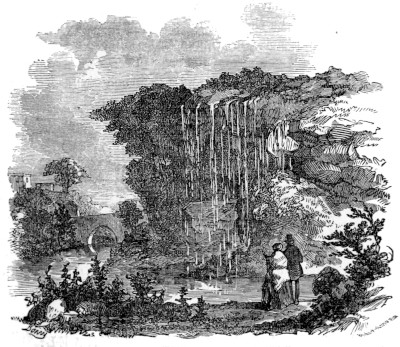

| Dropping Well at Knaresborough |

283 |

| Broseley Spring |

284 |

| Hot Springs of St. Michael |

284 |

| 6Hot Springs of the Troad |

285 |

| Other Springs |

286 |

| |

|

| BITUMINOUS AND OTHER LAKES. |

| Pitch Lake of Trinidad |

290 |

| Mud Lake of Java |

291 |

| Salt Lake of Utah |

292 |

| |

|

| ATMOSPHERICAL PHENOMENA. |

| Meteors |

294 |

| Aerolites |

307 |

| Aurora Borealis and Aurora Australis |

312 |

| Lumen Boreale, or Streaming Lights |

314 |

| Luminous Arches |

316 |

| Ignes Fatui, or Mock Fires |

317 |

| Specter of the Brocken |

319 |

| The Mirage |

322 |

| Fata Morgana |

323 |

| Atmospherical Refraction |

324 |

| Parhelia, or Mock Suns |

328 |

| Lunar Rainbow |

330 |

| Concentric Rainbows |

330 |

| Thunder and Lightning |

331 |

| Remarkable Thunder-Storms |

334 |

| Hail-Storms |

338 |

| Hurricanes |

339 |

| The Monsoons |

341 |

| Whirlwinds and Waterspouts |

342 |

| Sounds and Echoes |

348 |

| |

|

| BURIED CITIES. |

| The Yanar, or Perpetual Fire |

350 |

| Pompeii |

351 |

| The Museum at Naples |

360 |

| Herculaneum |

362 |

| Pompeii |

365 |

| The Museum |

375 |

| Herculaneum |

379 |

| |

|

| EARTHQUAKES. |

| Introductory |

384 |

| Earthquakes of Ancient Times |

389 |

| Earthquake in Calabria |

389 |

| The Great Earthquake of 1755 |

391 |

| Earthquake in Sicily and in the Two Calabrias |

401 |

| Earthquakes in Peru |

409 |

| Earthquake in Jamaica, 1692 |

411 |

| Earthquake in Venezuela, 1812 |

412 |

| |

|

| CONNECTION OF EARTHQUAKES WITH VOLCANOES. |

| Island of Java |

413 |

| |

|

| BASALTIC AND ROCKY WONDERS. |

| The Giant’s Causeway |

417 |

| Basaltic Columns |

422 |

| |

|

| NATURAL BRIDGES. |

| Natural Bridges of Icononzo |

424 |

| Natural Bridge in Virginia |

427 |

| |

|

| PRECIPICES AND PROMONTORIES. |

| Besseley Ghaut |

432 |

| The Cape of the Winds |

433 |

| The North Cape |

435 |

| Precipices of San Antonia |

436 |

| |

|

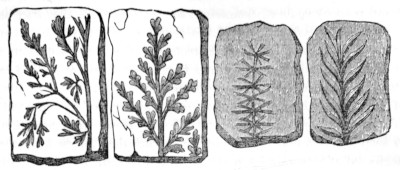

| GEOLOGICAL CHANGES OF THE EARTH. |

| Introductory |

438 |

| Extraneous Fossils |

446 |

| Fossil Crocodiles |

448 |

| Large Fossil Animal of Maestricht |

449 |

| Fossil Remains of Ruminantia |

450 |

| Fossil Remains of Elephants |

451 |

| Fossil Remains of the Mastodon |

453 |

| Fossil Remains of the Rhinoceros |

454 |

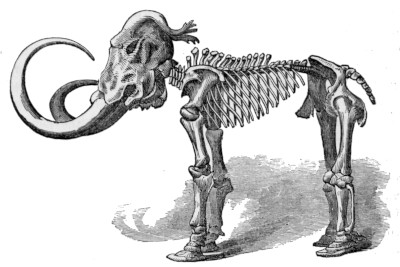

| Fossil Remains of the Siberian Mammoth |

455 |

| Fossil Shells |

457 |

| Subterranean Forests |

458 |

| Moors, Mosses and Bogs |

460 |

| Coral Reefs and Islands |

465 |

| |

|

| WIDE AND INHOSPITABLE DESERTS. |

| Asiatic Deserts |

469 |

| Arabian Deserts |

470 |

| African Deserts |

470 |

| Pilgrimage across the Deserts |

474 |

| Sands of the Desert |

486 |

| |

|

| WONDERS OF ART. |

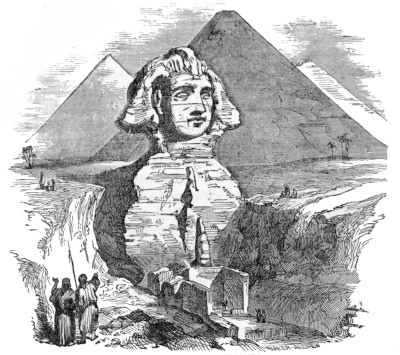

| The Pyramids of Egypt |

491 |

| The Tombs at Sakkara |

506 |

| The Sphinx |

509 |

| Ruins and Pyramids of Meroë |

511 |

| Pyramids and Ruins of Merawe |

516 |

| Egyptian Temples and Monuments |

520 |

| Bathing in the East |

526 |

| Egyptian Temples, Monuments, &c. |

527 |

| Other Ruins in Egypt, &c. |

554 |

| The River Nile |

562 |

| The African Birds-nest |

568 |

| Ruins of Palmyra |

569 |

| Ruins of Balbec |

570 |

| Ruins of Babylon |

572 |

| Babylonian Bricks |

579 |

| Later Discoveries at Babylon |

580 |

| Ruins of Nineveh |

582 |

| The Ruins of Persepolis |

587 |

| Royal Palace of Ispahan |

589 |

| The Temple of Mecca |

589 |

| |

|

| THE HOLY LAND. |

| Jacob’s Well |

591 |

| Bethlehem |

592 |

| Nazareth |

594 |

| The Holy Sepulcher at Jerusalem |

594 |

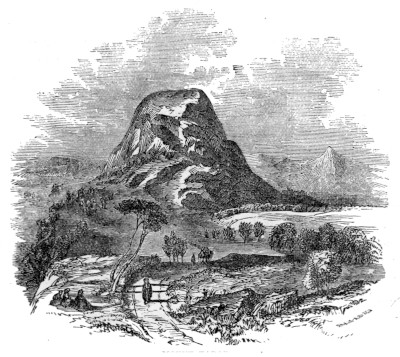

| 7Mount Tabor |

596 |

| The Mount of Olives |

598 |

| Other Revered Sites |

599 |

| Mount Carmel |

599 |

| Mount Ararat |

600 |

| |

|

| WONDERS OF ART RESUMED. |

| The Mosque of Omar |

601 |

| Mosque of St. Sophia at Constantinople |

602 |

| Ruins of Carthage |

603 |

| The Plain of Troy |

604 |

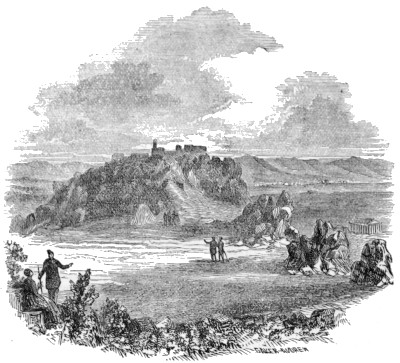

| Athens |

607 |

| Temples of Elephants |

610 |

| Temples of Salsette |

612 |

| Mausoleum of Hyder Ali |

614 |

| The Taje Mahal |

614 |

| Great Wall of China |

616 |

| Porcelain Tower at Nankin |

618 |

| The Shoemadoo at Pegu |

618 |

| Colossal Figure of Jupiter Pluvius, or the Apennine Jupiter |

621 |

| The Leaning, or Hanging Tower of Pisa, in Tuscany |

624 |

| The Coliseum at Rome |

627 |

| The Pantheon |

630 |

| Roman Amphitheater at Nismes |

632 |

| Trajan’s Pillar |

634 |

| Column of Antonine |

635 |

| Naison Carré, at Nismes |

635 |

| The Pont du Gard |

636 |

| Ancient Aqueduct near Rome |

637 |

| The Roman Forum |

638 |

| St. Peter’s of Rome |

642 |

| The Soil of Rome |

646 |

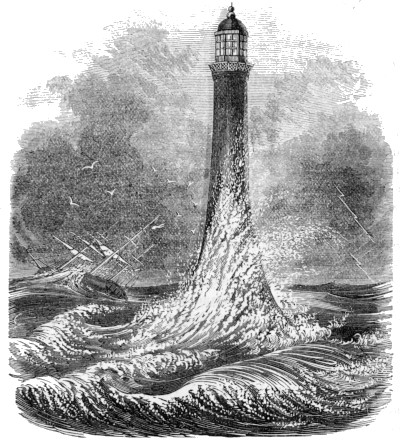

| Eddystone Light-house |

647 |

| Bell Rock Light-house |

649 |

| Stonehenge |

652 |

| Rocking Stones |

654 |

| The Round Towers of Ireland |

656 |

| St. Paul’s Cathedral |

657 |

| First Church in England |

661 |

| Westminster Abbey |

662 |

| Cathedral of Notre Dame |

665 |

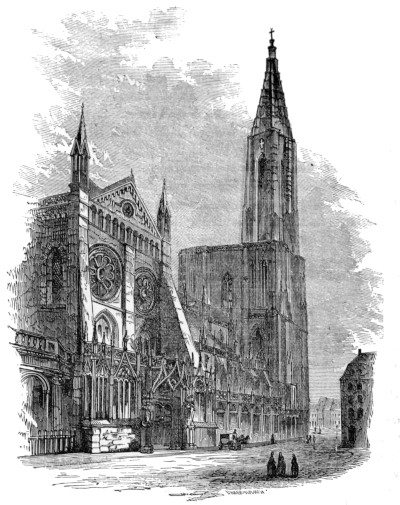

| Strasburg Cathedral |

665 |

| Cathedral of Cologne |

669 |

| Church of St. Mark, at Venice |

669 |

| The Cathedral of Milan |

670 |

| The Tower of London |

671 |

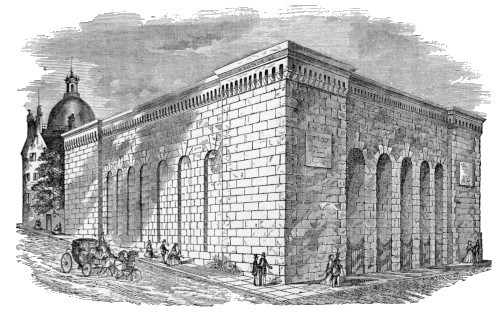

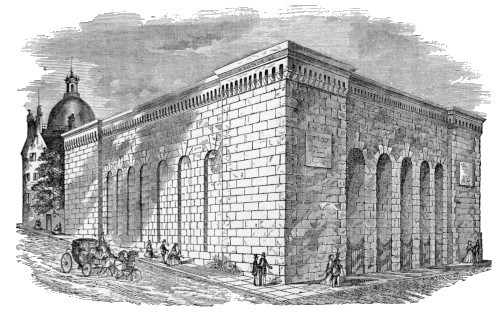

| The Bank of England |

674 |

| Monument of the Great Fire of 1666 in London |

675 |

| The Louvre |

676 |

| The British Museum |

679 |

| Madame Tusseau’s Museum |

686 |

| The Palace of Blenheim |

689 |

| The Palace of Versailles |

691 |

| The Palace of St. Cloud |

693 |

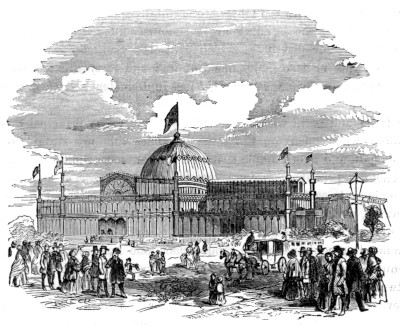

| The Crystal Palace in New York |

697 |

| The Crystal Palace in London |

702 |

| The Capitol at Washington |

712 |

| The Smithsonian Institute |

714 |

| The Washington Monument |

715 |

| The Column of Vendome, Paris |

718 |

| The Bunker Hill Monument |

719 |

| The Arc de Triomphe (Paris) |

721 |

| The Cooper Institute (New York) |

723 |

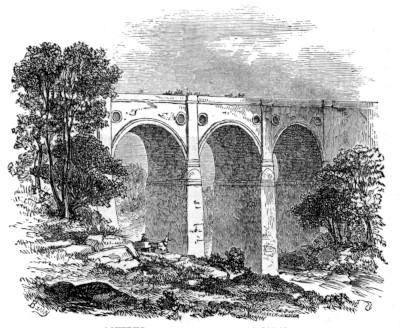

| Vergnais’s Improved Bridge over the Seine at Paris |

725 |

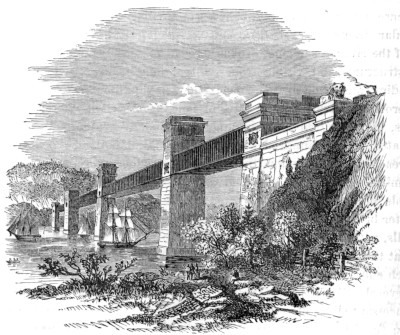

| Railroad Bridge at Portage, New York |

726 |

| The Britannia Tubular Bridge, over Menai Strait |

728 |

| The Suspension Bridge over the Menai Strait |

730 |

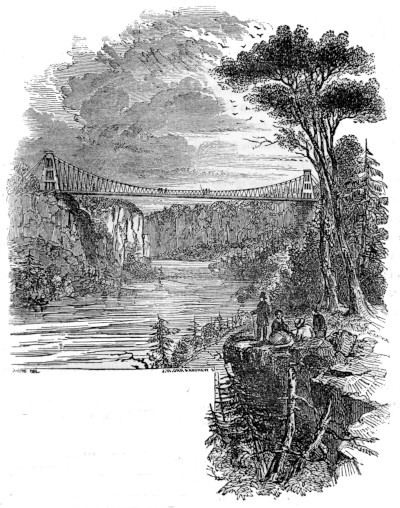

| Great Railway Suspension Bridge at Niagara Falls |

731 |

| Other Immense Bridges |

732 |

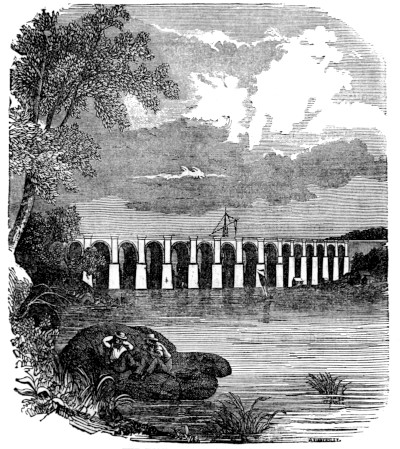

| The High Bridge at Harlem |

733 |

| The Boston Reservoir |

734 |

| Aqueduct at the Peat Forest Canal (England) |

735 |

| The Thames Tunnel |

737 |

| Railroad Tunnels |

739 |

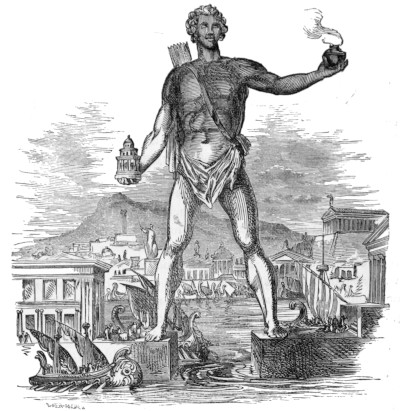

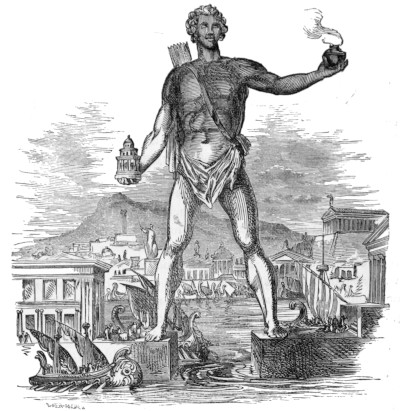

| The Colossus at Rhodes |

741 |

| |

|

| MISCELLANEOUS WONDERS. |

| Youle’s Shot-Tower |

744 |

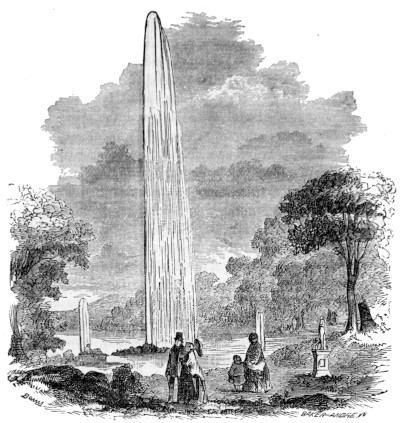

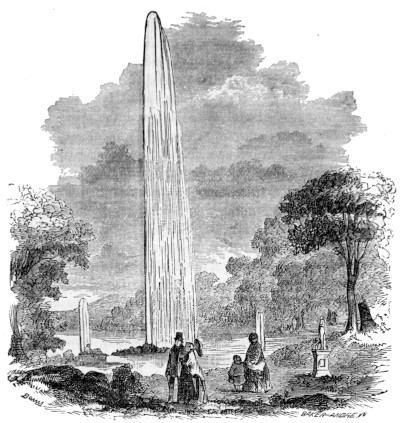

| The Emperor Fountain |

746 |

| The United States Mint in Philadelphia |

747 |

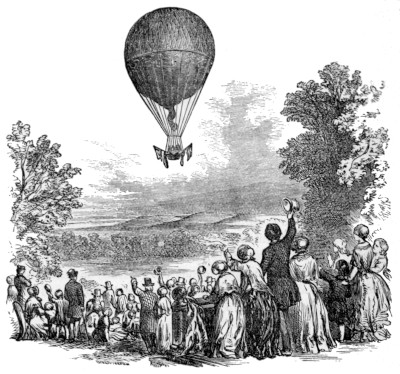

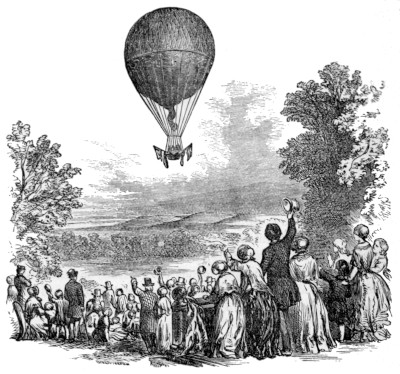

| The Air Balloon |

749 |

| The Progress of Navigation |

755 |

| Steam Navigation |

758 |

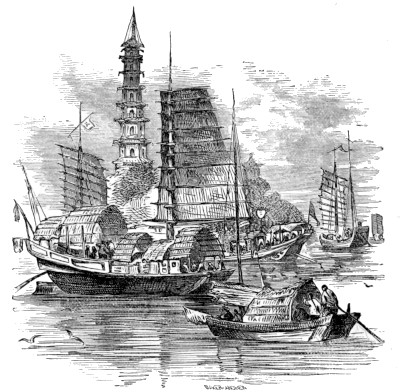

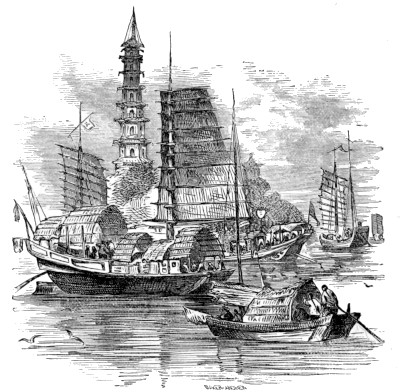

| Chinese Junks |

766 |

| The Artesian Well of Grenelle |

767 |

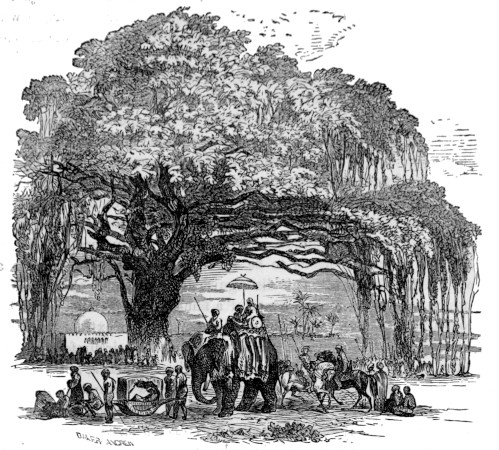

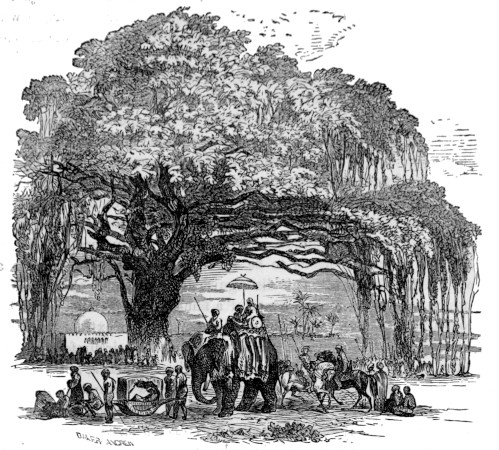

| The Banyan-Tree |

768 |

| The Wedded Banyan-Tree |

771 |

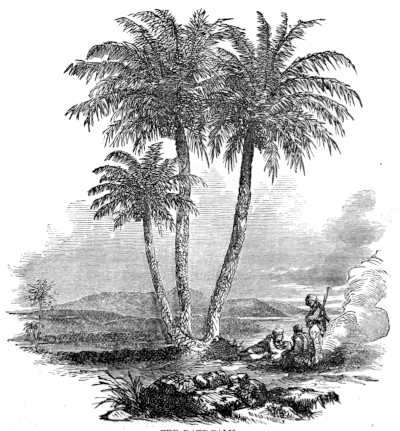

| The Cocoa-Tree |

771 |

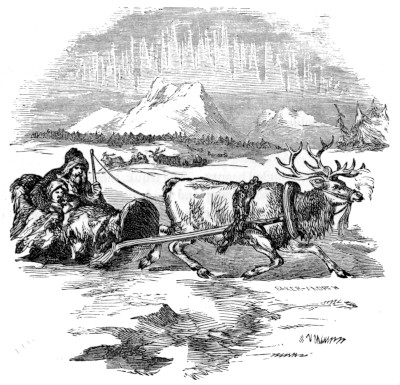

| The Reindeer Sledge |

772 |

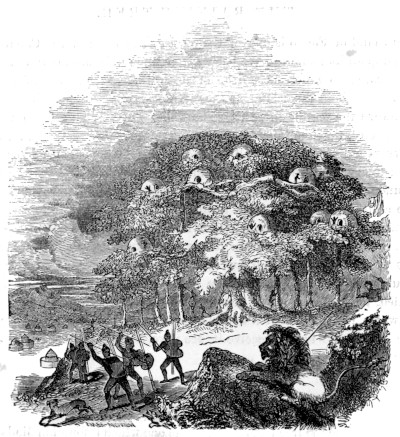

| The Upas or Poison-Tree |

773 |

| The Prairie on Fire |

775 |

| The Mammoth Tree of California |

776 |

| Other Mammoth Trees in California |

778 |

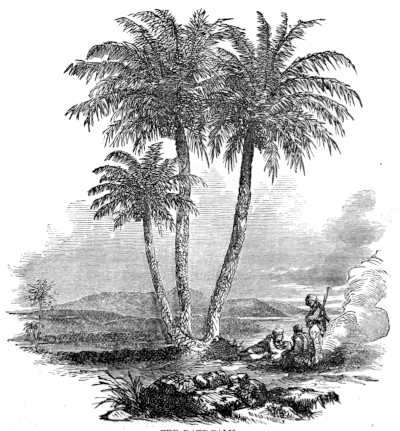

| The Palm-Tree |

778 |

| The Bamboo-Tree |

781 |

| The Manna-Tree |

783 |

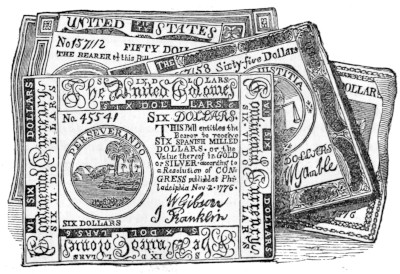

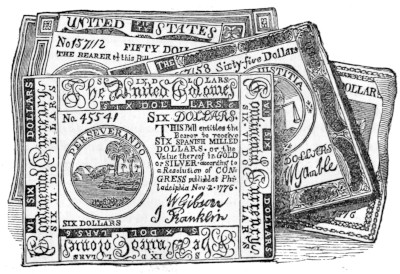

| Continental Money |

783 |

| The Milk-Tree |

784 |

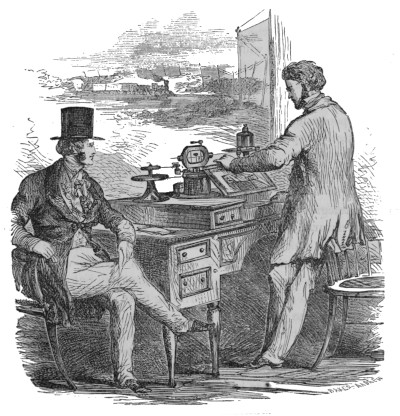

| The Signal Telegraph |

786 |

| The Electro-Magnetic Telegraph |

787 |

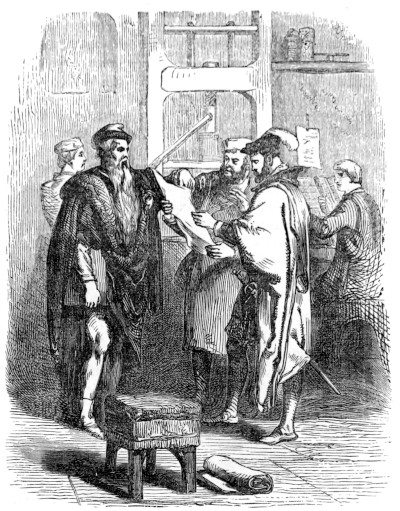

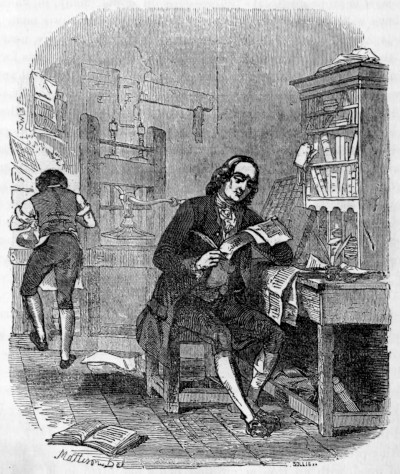

| The Art of Printing |

788 |

| The India-Rubber Tree |

793 |

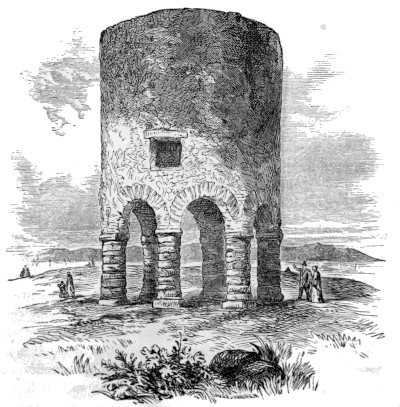

| The Round Tower at Newport |

795 |

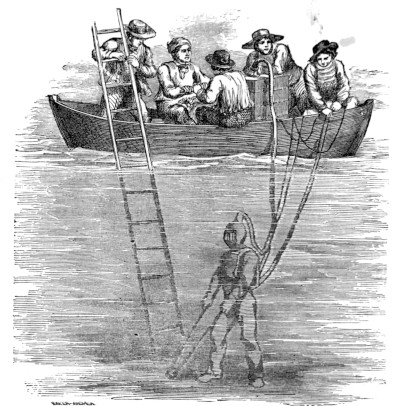

| Diving Armor |

796 |

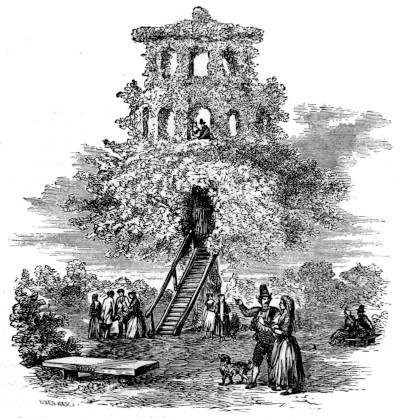

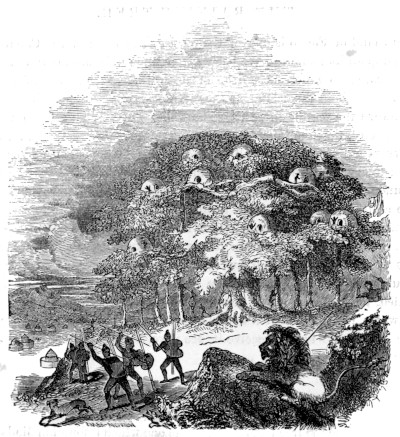

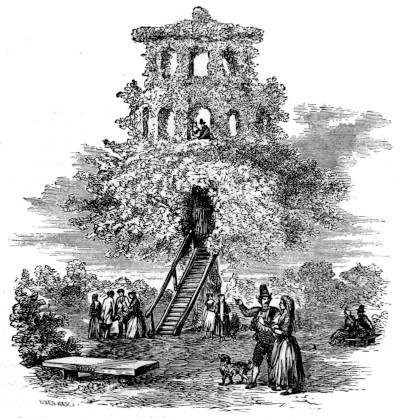

| Tree House in Caffraria |

799 |

| The Raining-Tree |

800 |

| The Traveler’s Friend |

800 |

| The Camphor-Tree |

801 |

| The Cinnamon Plant |

802 |

| The Tree Temple at Matibo in Piedmont |

803 |

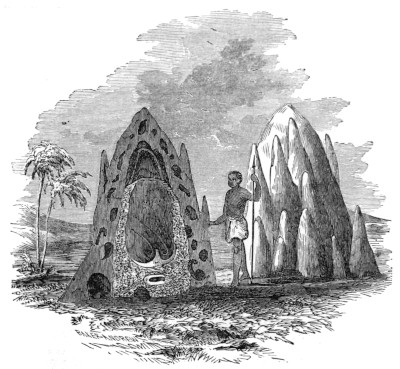

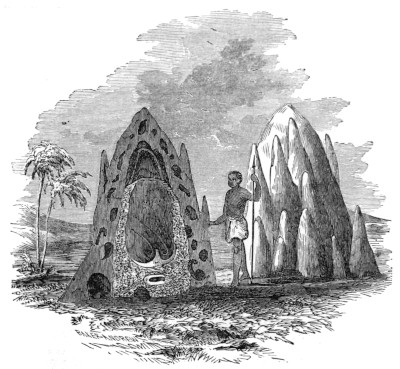

| The Termites, or White Ants |

804 |

| Huts in Kamtschatka |

806 |

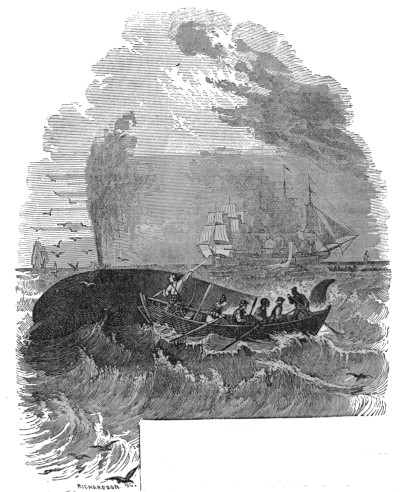

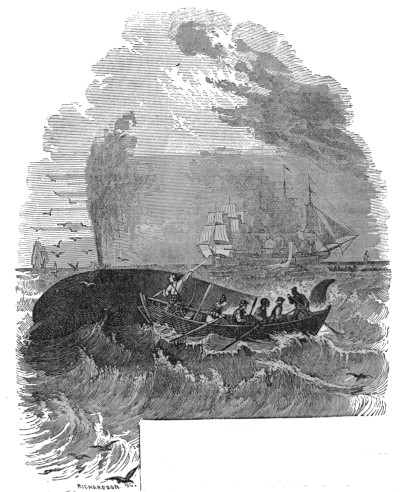

| The Whale |

807 |

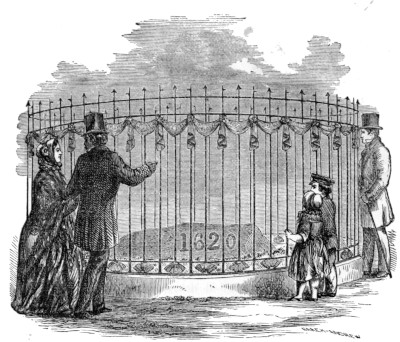

| Landing of the Pilgrims |

808 |

| Plymouth Rock |

809 |

| A Wonder of Art |

811 |

| The Whale Killer |

812 |

| A Pile of Serpents |

813 |

| American Ruins |

814 |

| Insect Slavery |

815 |

8

List of Illustrations.

| |

PAGE. |

| The Cordilleras, or Andes, near Quito |

10 |

| Crater of Mount Etna |

16 |

| The “Castano de Cento Cavilli,” or Great Chestnut Tree of Mount Etna |

18 |

| Mount Vesuvius |

22 |

| Mount Hecla and the Geysers |

29 |

| Mont Blanc and the Glaciers |

38 |

| The Peak of Teneriffe |

59 |

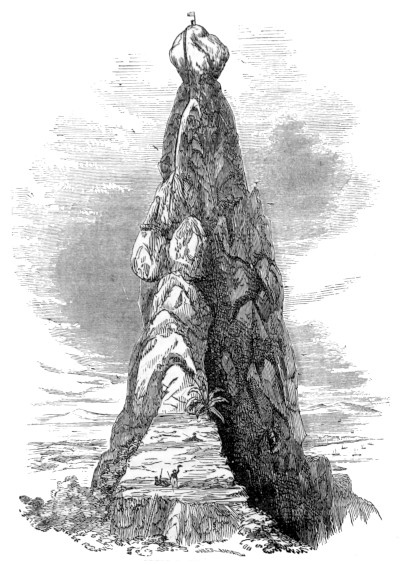

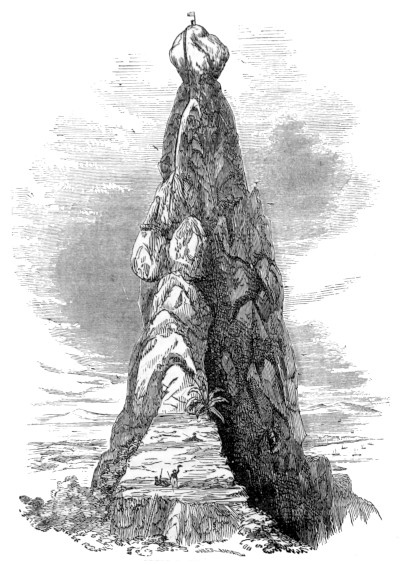

| Peter Botte’s Mountain |

74 |

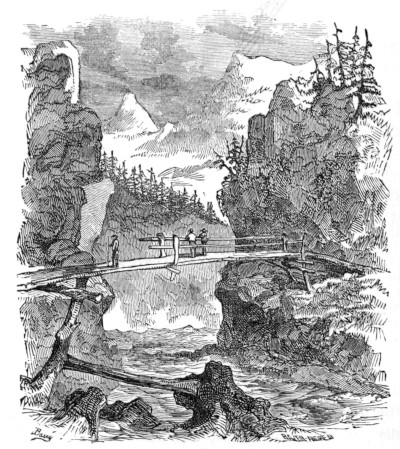

| Bridge over the Wye |

92 |

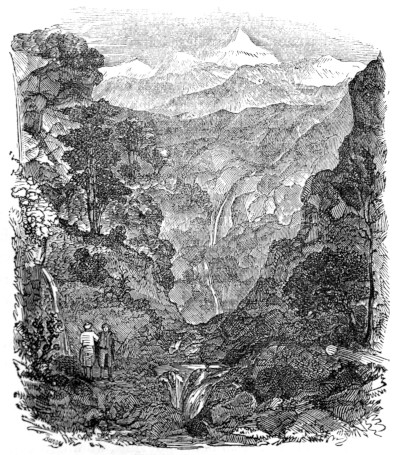

| Source of the Jumna |

109 |

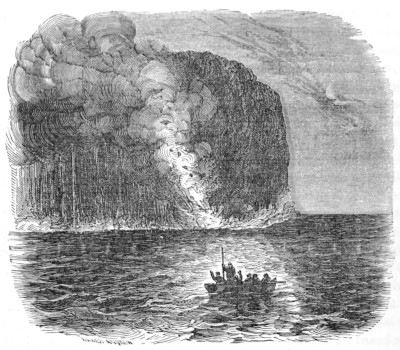

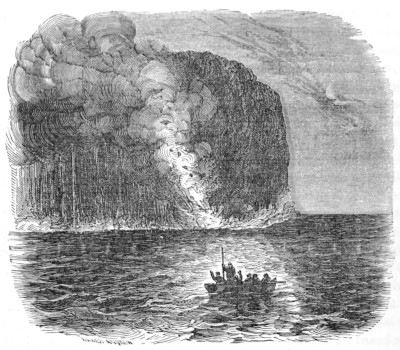

| St. Michael’s Volcano |

122 |

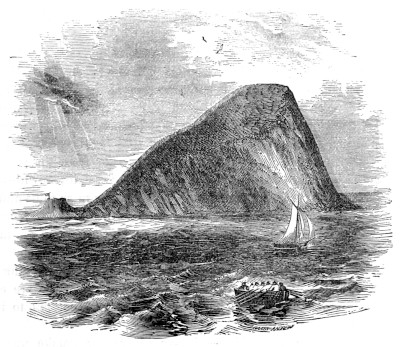

| Sabrina Island |

125 |

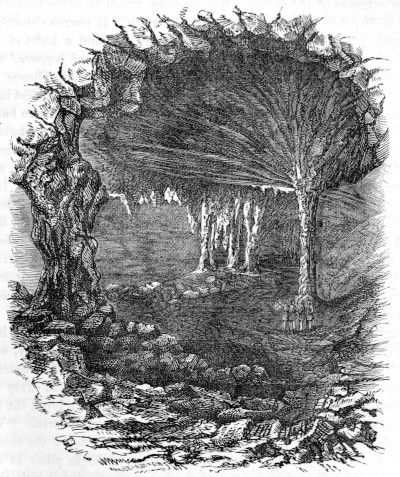

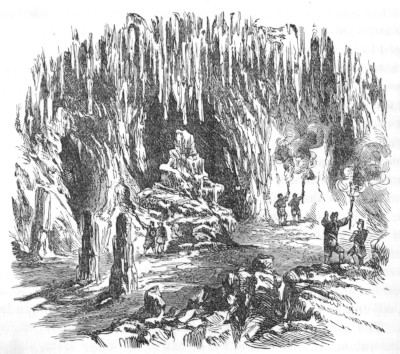

| Grotto of Antiparos |

136 |

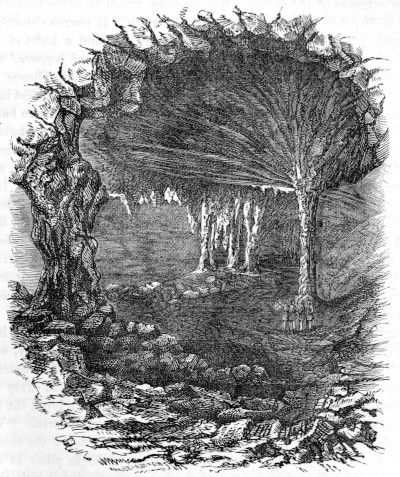

| The Mammoth Cave |

141 |

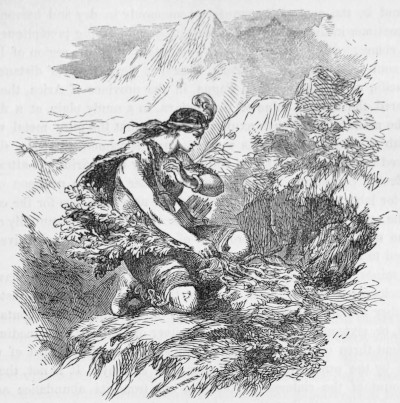

| Diamond Washing in Brazil |

171 |

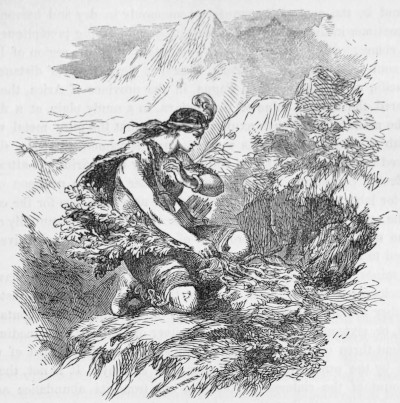

| Discovery of Silver in Peru |

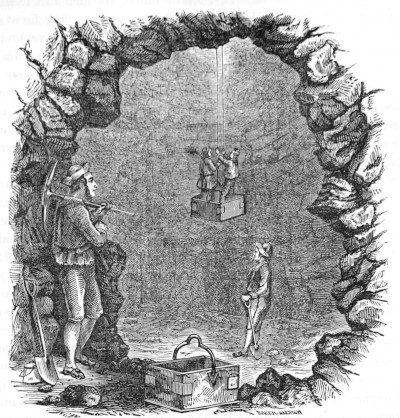

179 |

| Silver Mine at Königsberg, Sweden |

185 |

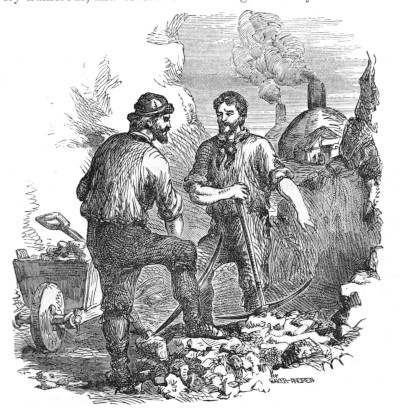

| Gold Washing in California |

188 |

| Place where Gold was first discovered in Australia |

190 |

| Copper Mine in Cornwall |

207 |

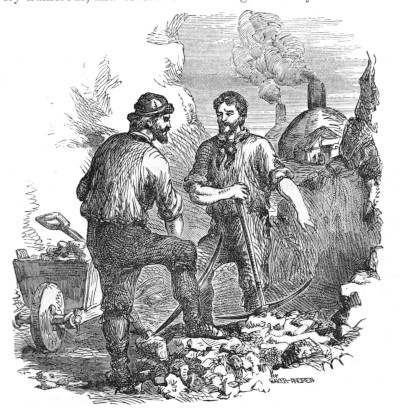

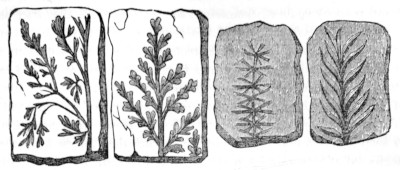

| Thin Plates of Coal |

213 |

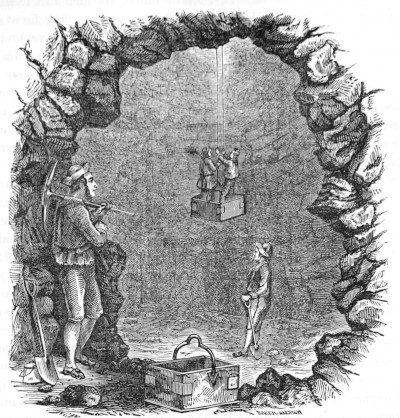

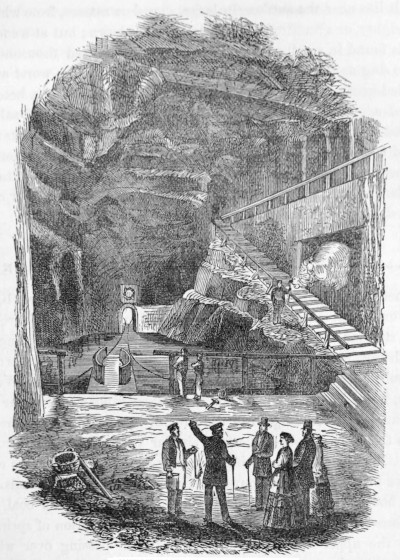

| Great Salt Mine of Cracow |

225 |

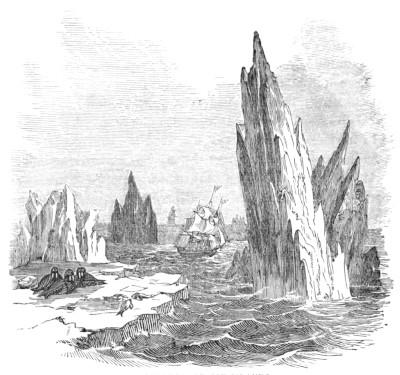

| Icebergs, or Ice-Islands |

236 |

| The Maelstrom |

250 |

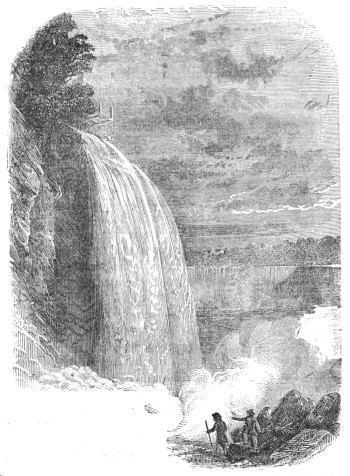

| Niagara Falls |

256 |

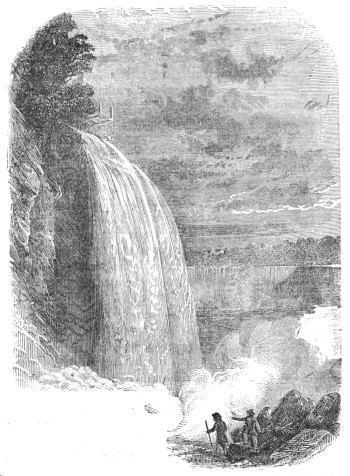

| Niagara Falls on the American side |

259 |

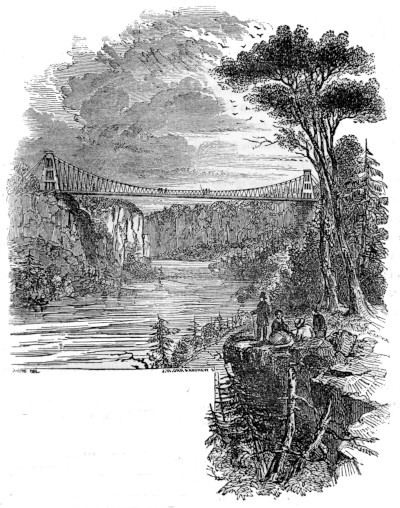

| Suspension Bridge over Niagara River |

265 |

| Falls of Montmorenci |

270 |

| Catskill Falls |

274 |

| Dropping Well at Knaresborough, England |

283 |

| The Emigrant Family |

293 |

| Specter of the Brocken |

320 |

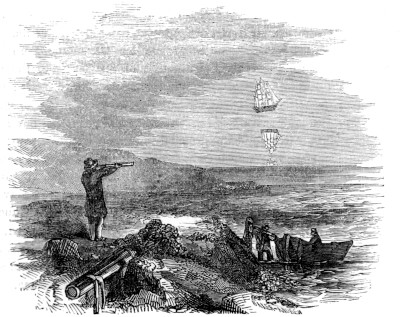

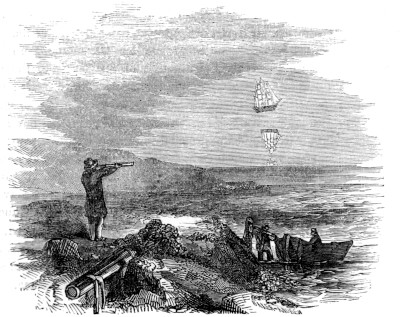

| Ship refracted in the Air |

327 |

| Waterspout on the Ocean |

346 |

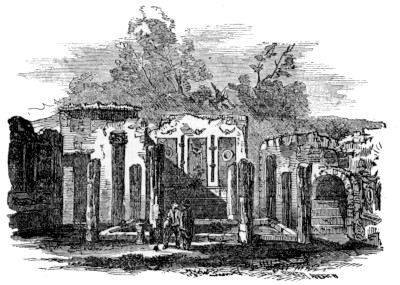

| Temple of Isis at Pompeii |

356 |

| Papyri |

361 |

| Earthquake at Lisbon |

394 |

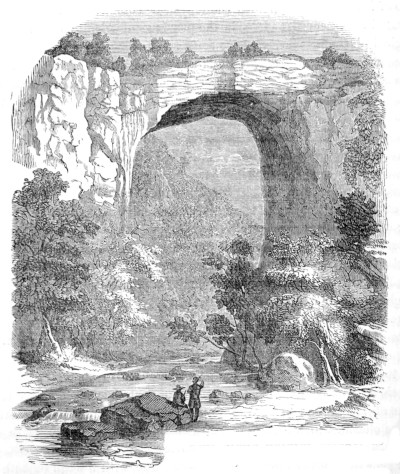

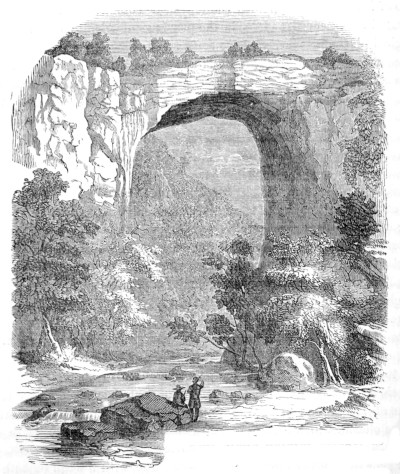

| Natural Bridge in Virginia |

428 |

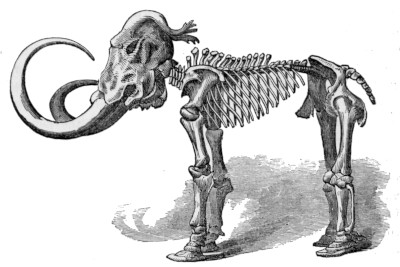

| Skeleton of the Siberian Mammoth |

456 |

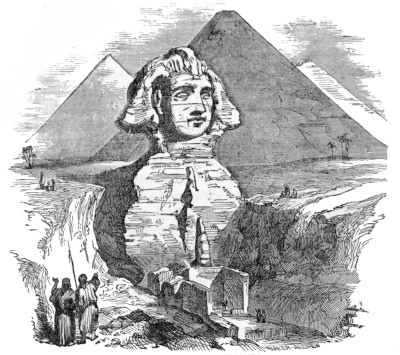

| The Sphinx and Pyramids |

492 |

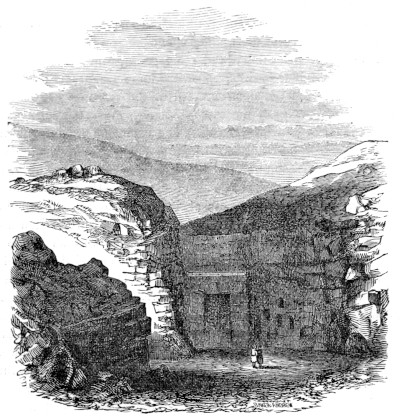

| Entrance to one of the Pyramids of Gizeh |

499 |

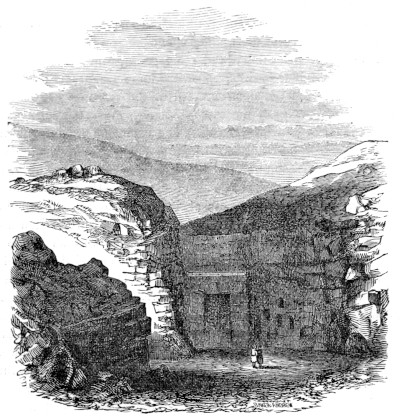

| Entrance to the Tombs of Sakkara |

507 |

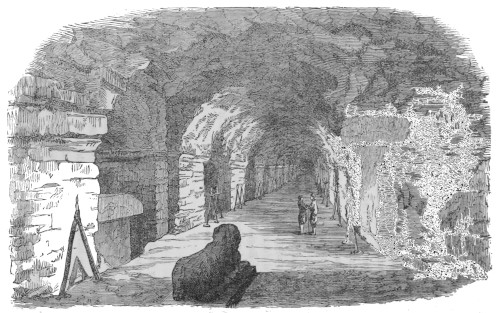

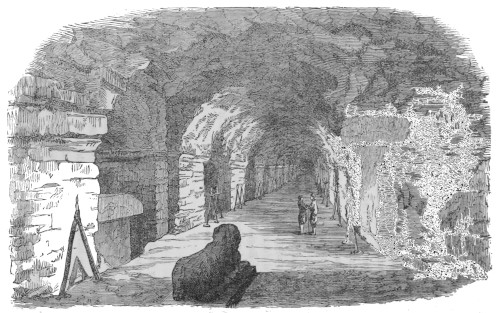

| Great Gallery of the Tombs of Sakkara |

510 |

| Cleopatra’s Needle |

521 |

| The Two Colossi |

535 |

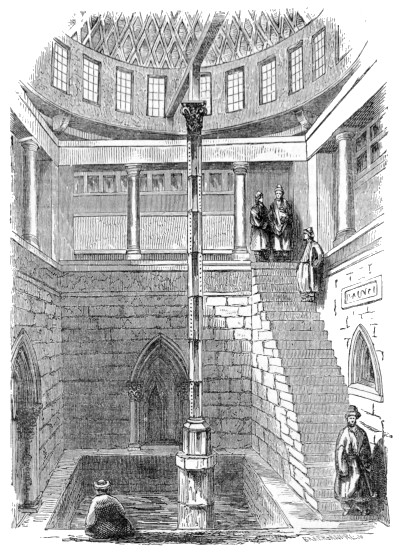

| The Nilometer |

565 |

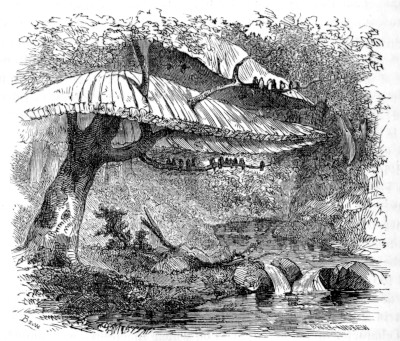

| African Birds-nest |

568 |

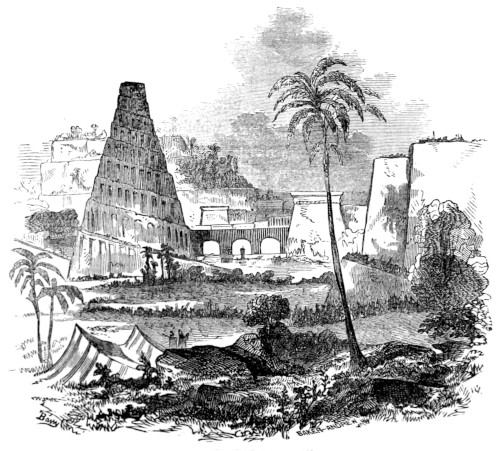

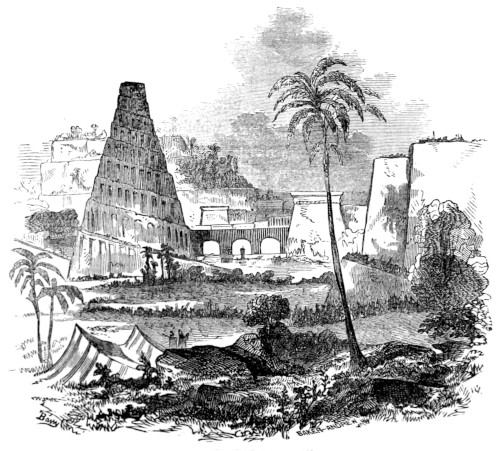

| Tower near Babylon |

573 |

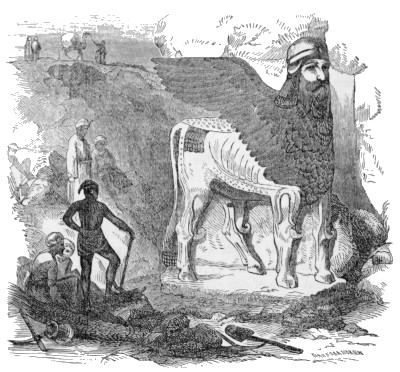

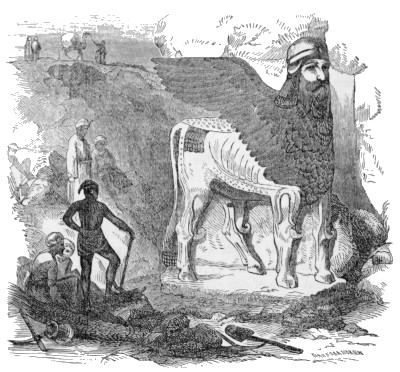

| Colossal Winged Bull from Nineveh |

584 |

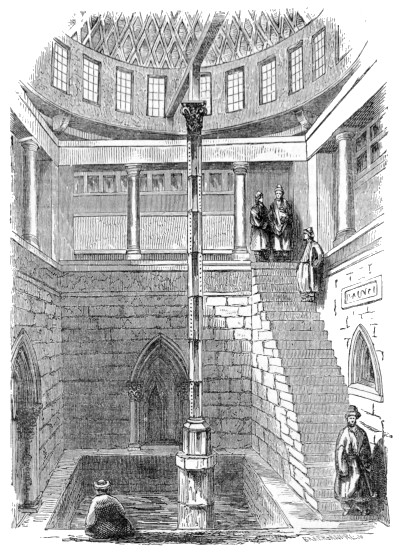

| Jacob’s Well |

591 |

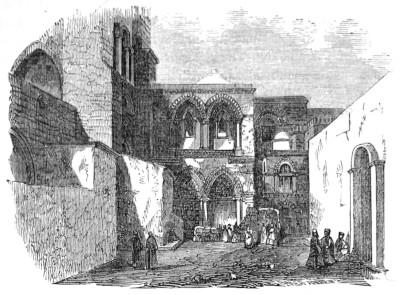

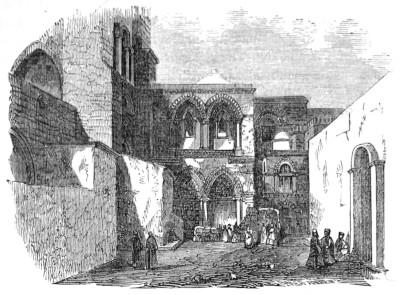

| Church of the Holy Sepulcher |

595 |

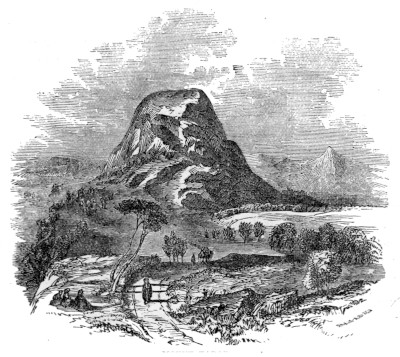

| Mount Tabor |

597 |

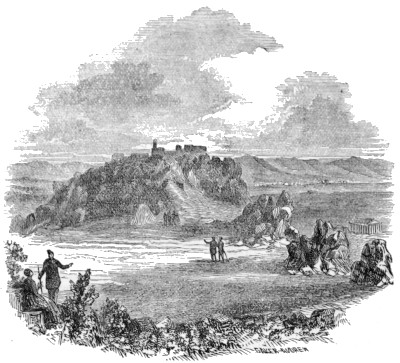

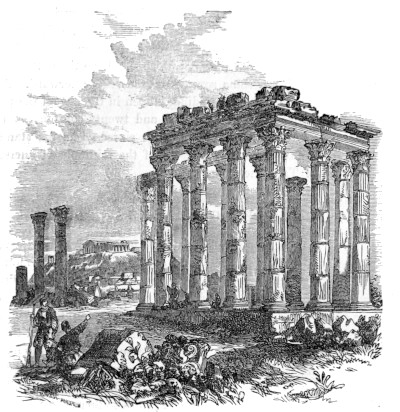

| The Areopagus |

608 |

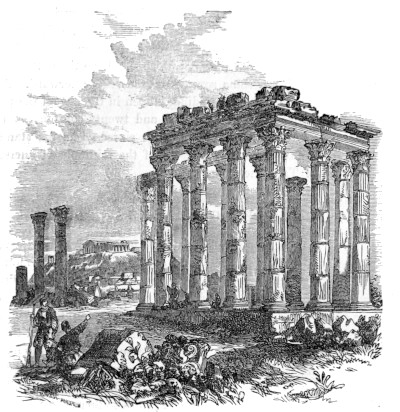

| Temple of Jupiter Olympius |

609 |

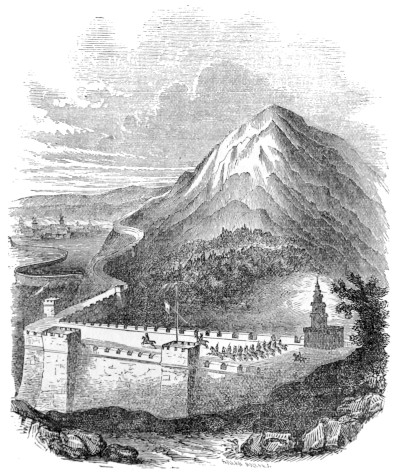

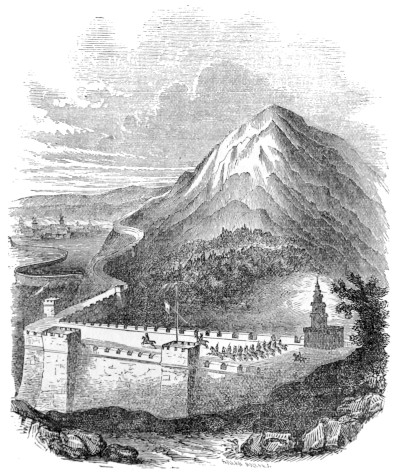

| Great Wall of China |

615 |

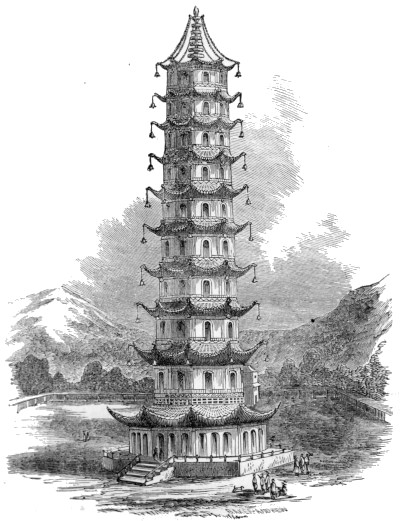

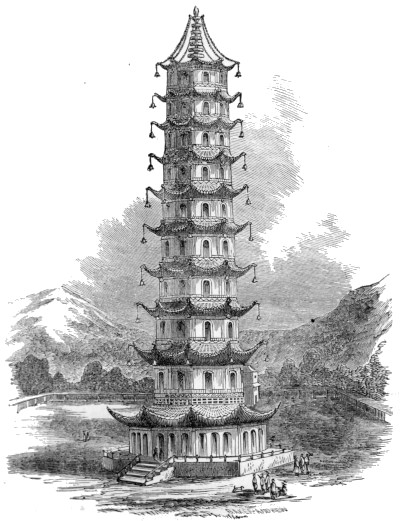

| Porcelain Tower at Nankin |

617 |

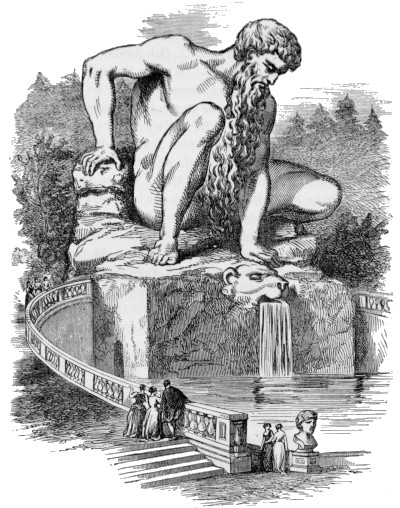

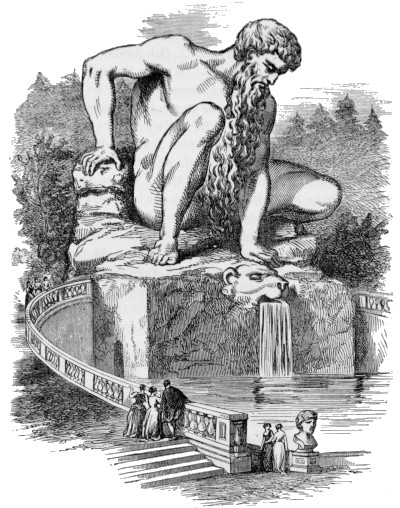

| Jupiter Pluvius, or the Apennine Jupiter |

622 |

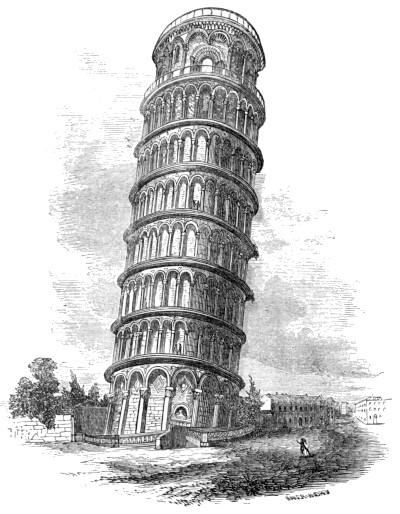

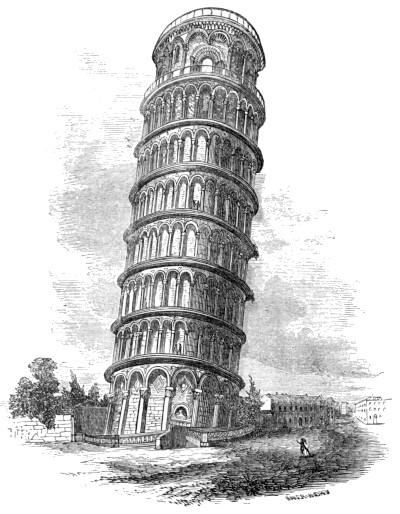

| The Leaning Tower at Pisa |

624 |

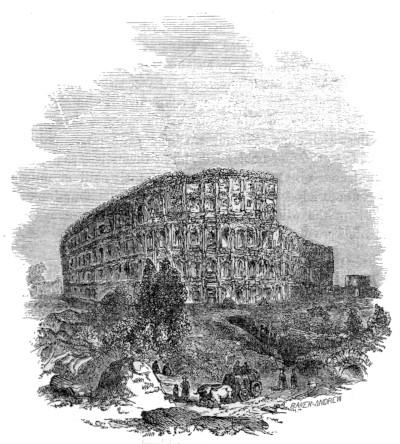

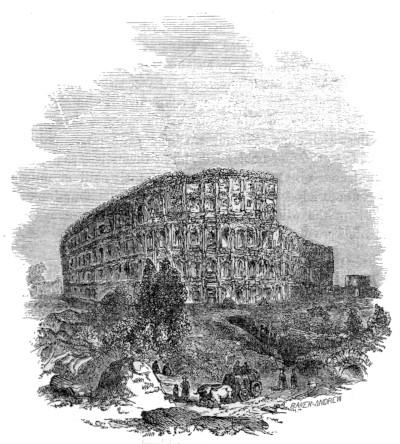

| The Coliseum at Rome |

629 |

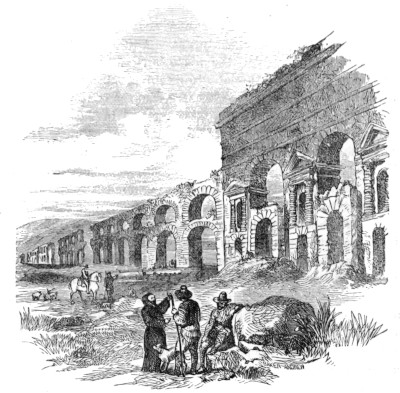

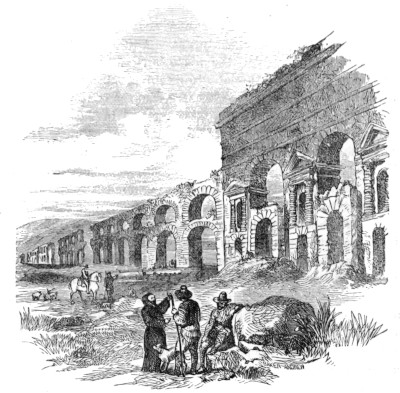

| Ancient Roman Aqueduct |

638 |

| The Arch of Titus |

640 |

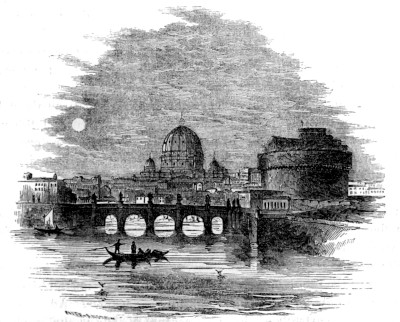

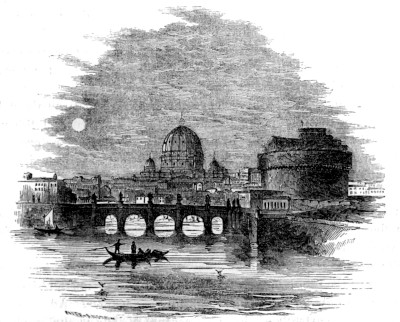

| St. Peter’s as seen from the Tiber |

643 |

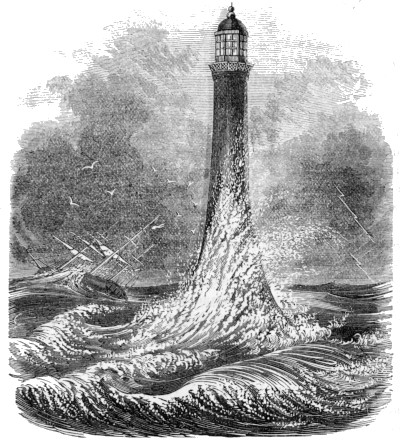

| The Eddystone Light-house |

648 |

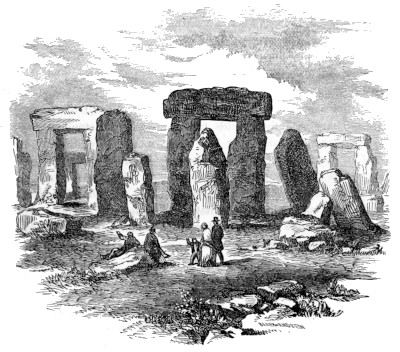

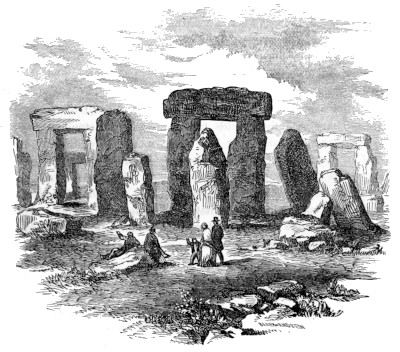

| Stonehenge |

653 |

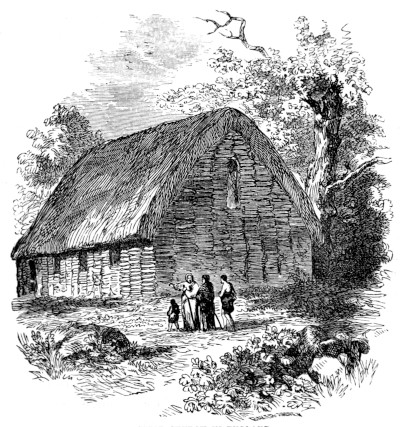

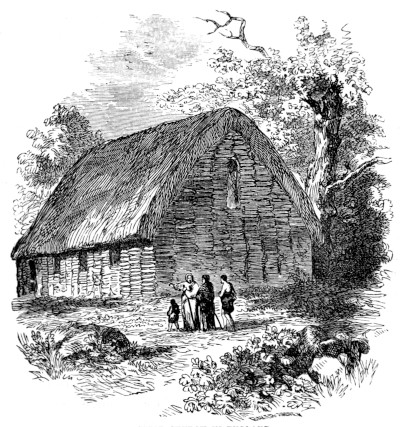

| The First Church in England |

661 |

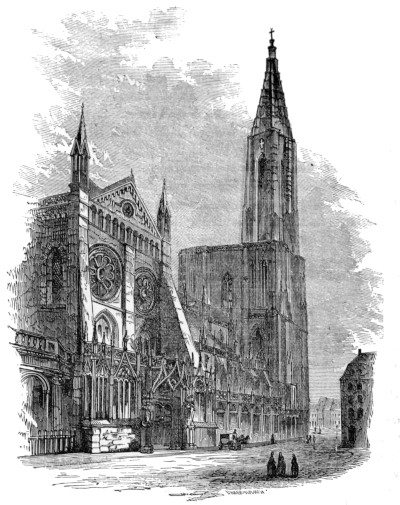

| Strasburg Cathedral |

666 |

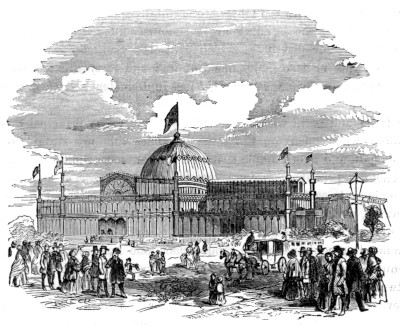

| The Crystal Palace in New York |

697 |

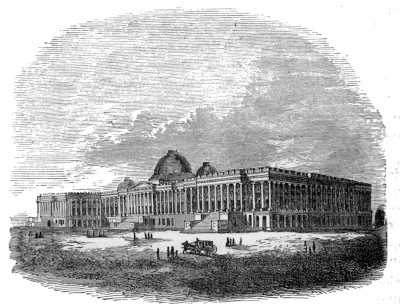

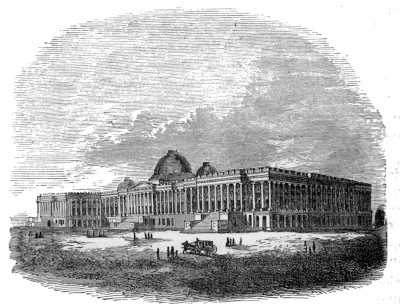

| The Capitol at Washington |

712 |

| The Smithsonian Institute |

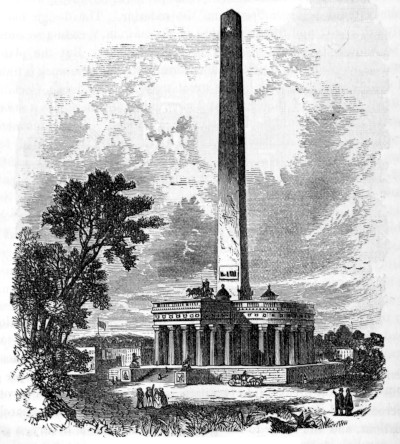

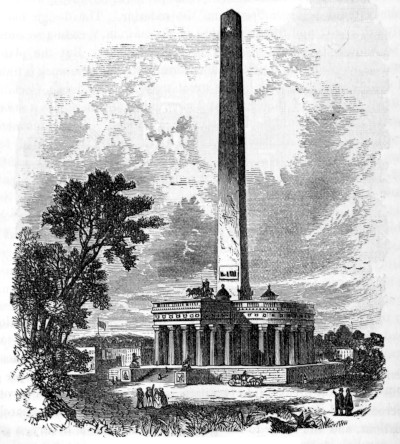

715 |

| The Washington Monument |

716 |

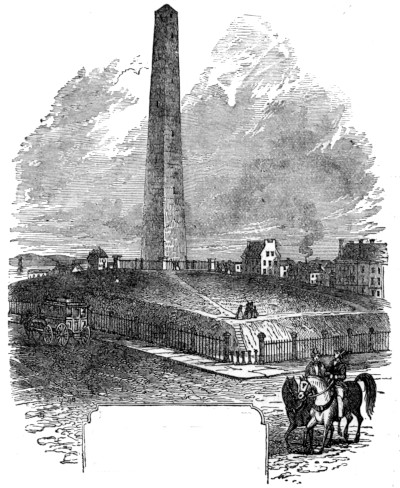

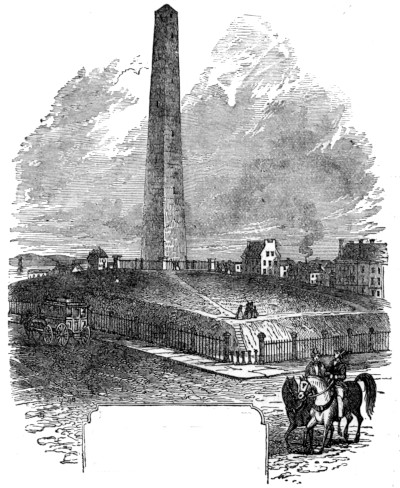

| The Bunker-Hill Monument |

720 |

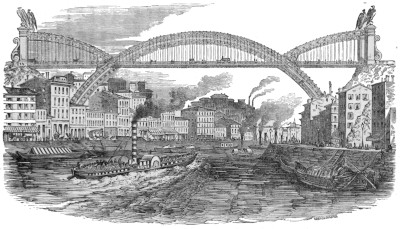

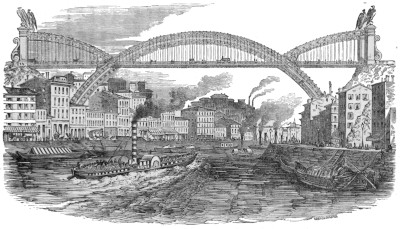

| Vergnais’s Herculean Bridge |

725 |

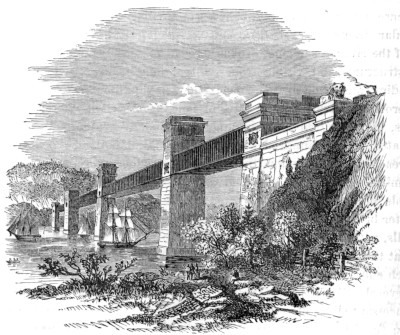

| The Britannia Tubular Bridge |

728 |

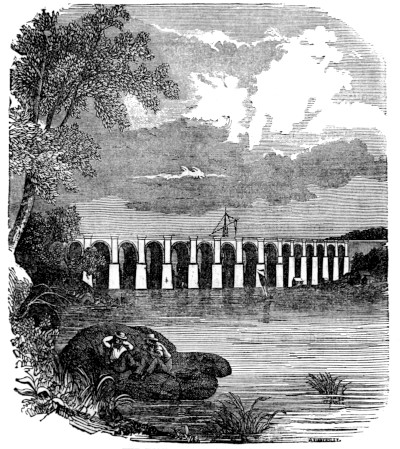

| The High Bridge at Harlem |

733 |

| The Boston Reservoir |

735 |

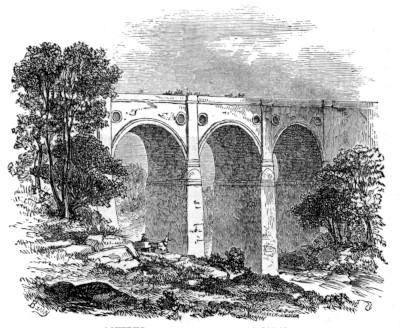

| Aqueduct on the Peat Forest Canal |

736 |

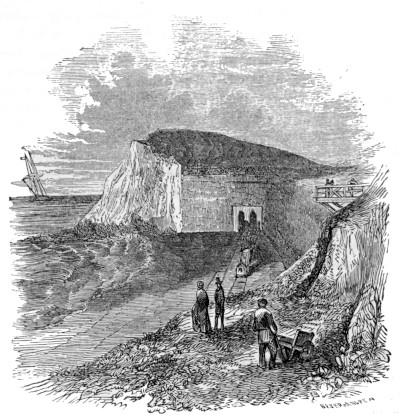

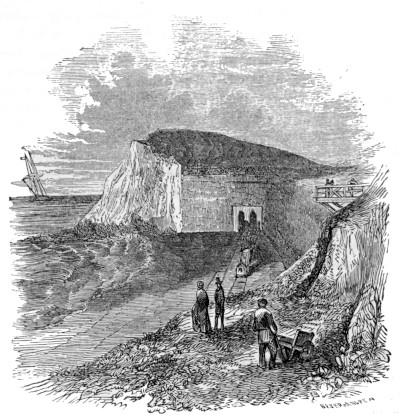

| Tunnel in Shakspeare’s Cliff |

740 |

| The Colossus of Rhodes |

742 |

| The Emperor Fountain |

747 |

| The Air Balloon |

750 |

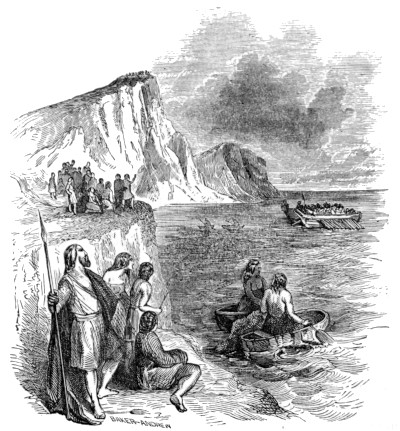

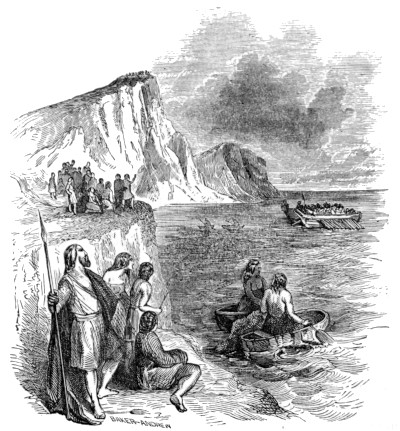

| Early Navigation |

756 |

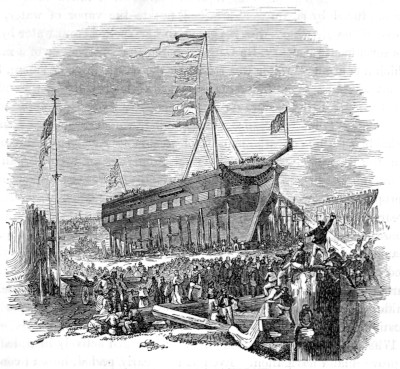

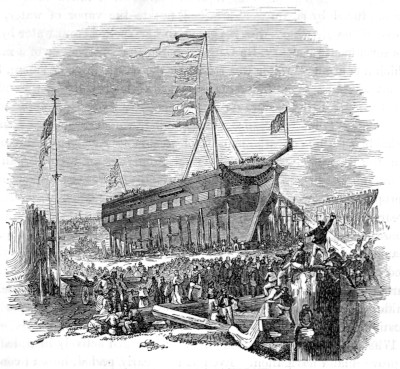

| The Launch of a Packet-Ship |

757 |

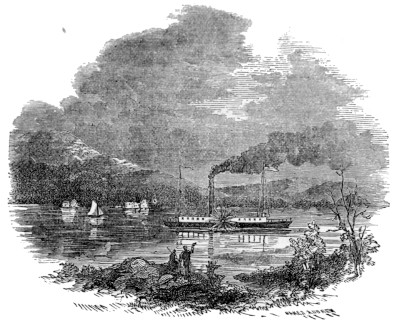

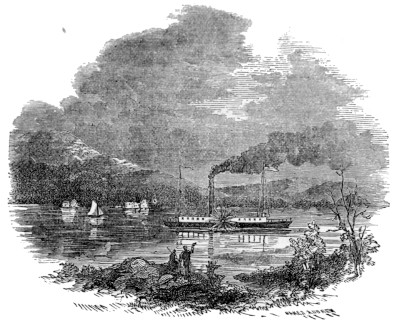

| Fulton’s First Steamboat |

759 |

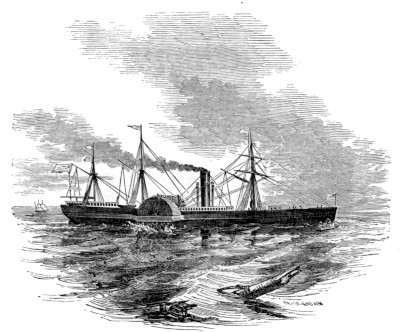

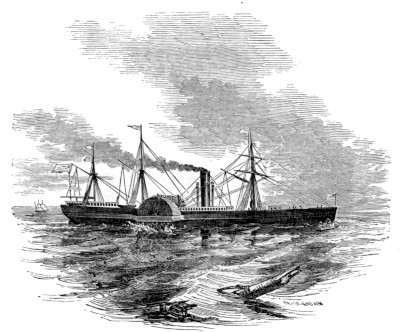

| An Ocean Steamer |

762 |

| Chinese Junks |

766 |

| The Banyan-Tree |

769 |

| The Reindeer Sledge |

772 |

| The Prairie on Fire |

775 |

| The Date-Palm |

779 |

| The Bamboo-Tree |

782 |

| Continental Money |

783 |

| The Signal Telegraph |

785 |

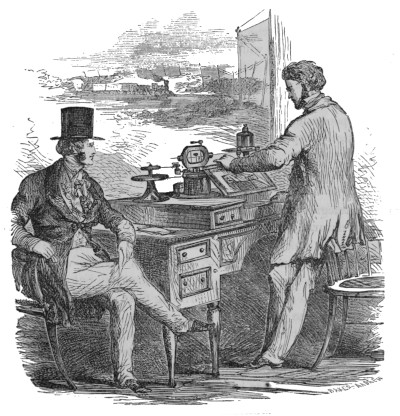

| The Electro-Magnetic Telegraph |

787 |

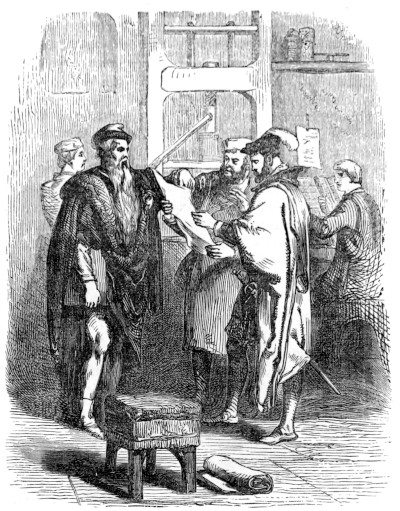

| Faust taking First Proof from movable types |

789 |

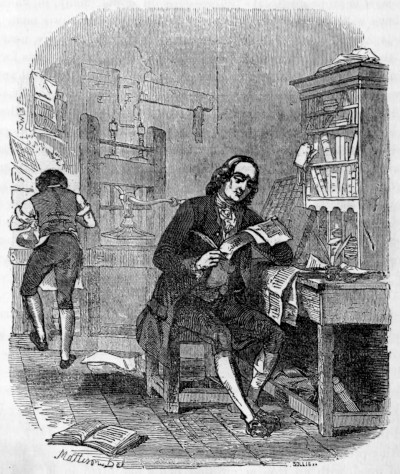

| Franklin’s Printing-Press |

790 |

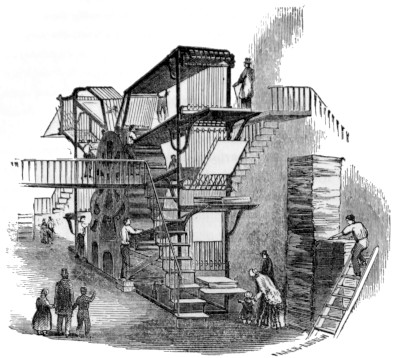

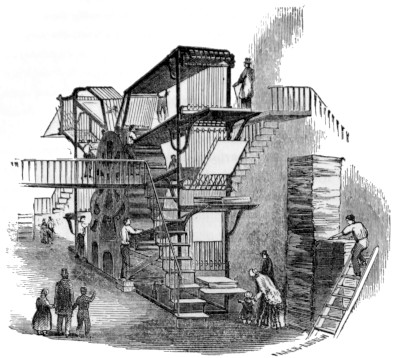

| Hoe’s Eight-Cylinder Power Press |

792 |

| The India-Rubber Tree |

793 |

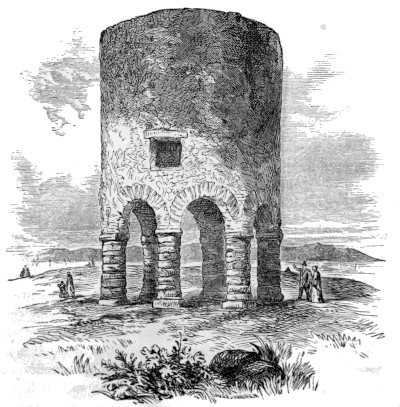

| The Old Round Tower at Newport |

795 |

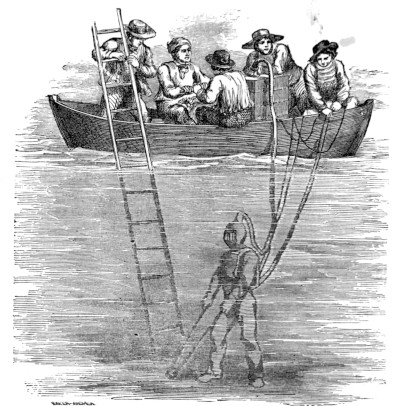

| Submarine or Diving Armor |

796 |

| Manner of working the Diving-Armor |

797 |

| Tree House in Caffraria |

799 |

| The Camphor-Tree |

801 |

| Tree Temple at Matibo in Piedmont |

803 |

| Ant-Hills of the White Ant |

805 |

| Huts in Kamtschatka |

806 |

| Taking a Whale |

807 |

| Landing of the Pilgrims |

809 |

| Plymouth Rock |

810 |

| Early Settlers of New England going to Church |

811 |

9THE

Wonders of the World.

MOUNTAINS.

“And lo! the mountains print the distant sky,

And o’er their airy tops faint clouds are driven,

So softly blending that the cheated eye,

Forgets or which is earth, or which is heaven!”—Fay.

“Mountains and all hills—let them praise the name of the Lord, for his name alone is excellent;

his glory is above the earth and heaven.”—David.

Among the wonders, or uncommon phenomena of the world, may be

classed stupendous mountains. For though compared with the entire

diameter of the earth, the highest elevations on its surface are no more than

the inequalities on the skin of the orange to the orange itself, yet to our eyes

they often appear immensely lofty and sublime. Descriptions of such vast

and striking objects often fail to excite corresponding ideas; so that however

accurate or poetical may be the accounts of this class of the prodigies of

nature, no just notions of their vastness can be conveyed, by any written

or graphical representation. The magnitude of an object must be seenseen to

be duly conceived; and the mountain-wonders of the world will best be

understood and felt by those who have visited Wales, Scotland, Switzerland,

or the mountainous regions of America or Asia.

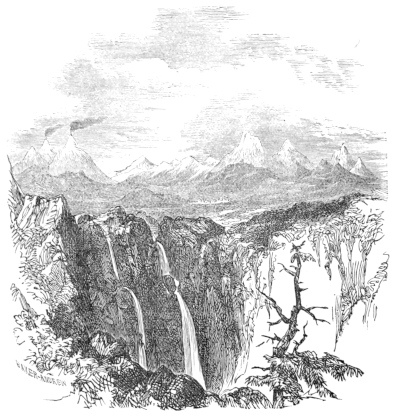

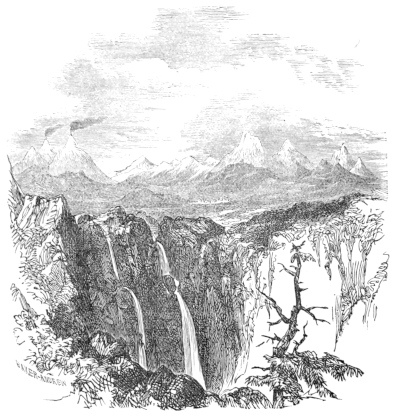

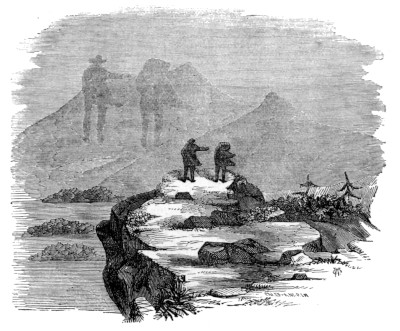

THE ANDES.

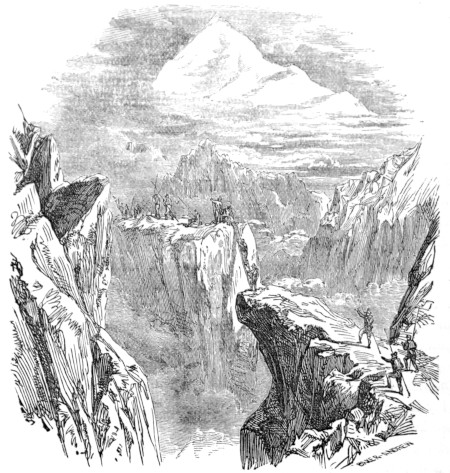

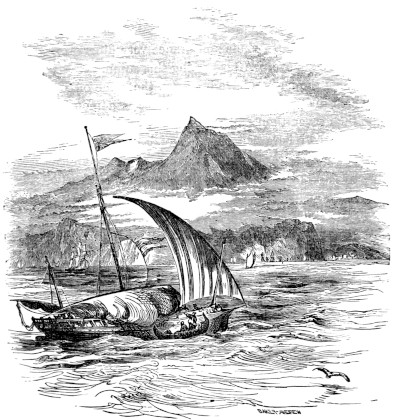

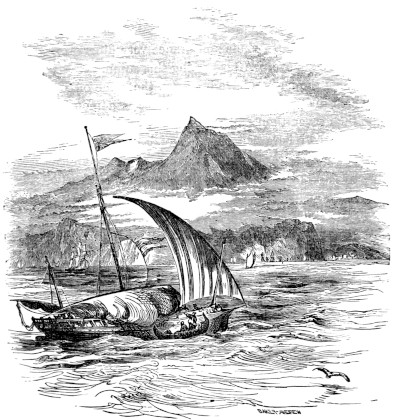

Some of the loftiest and most extensive mountains in the world, are the

Andes, in South America. These stupendous hills, called by the Spaniards

the Cordilleras, (from the word cord or chain,) i.e. the chains of the

10Andes, stretch north and south near the western coast, from the isthmus

of Darien, through the whole of the continent of South America, to the

straits of Magellan. In the north, there are three chains of separate ridges;

but in advancing from Popayan toward the south, the three chains unite

into a single group, which is continued far beyond the equator. In

Equador, near Quito, the more elevated summits of this group are ranged in

two rows, (as seen in the cut below,) which form a double crest to the

Cordilleras. The extent of the Andes mountains is not less than four thousand

three hundred miles, from one end to the other.

THE CORDILLERAS, OR ANDES, NEAR QUITO.

“Rocks rich in gems, and mountains big with mines,

That on the high equator ridgy rise,

Whence many a bursting stream auriferous plays.”—Thomson.

In this country, the operations of nature appear to have been carried on

on a larger scale, and with a bolder hand, than elsewhere; and in consequence,

the whole is distinguished by a peculiar magnificence. Even the

11plain of Quito, which may be considered as the base of the Andes, is more

elevated above the sea than the summits of many European mountains. In

different places the Andes rise more than one-third higher than the famous

peak of Teneriffe, the highest land in the ancient hemisphere. Their cloud-enveloped

summits, though exposed to the rays of the sun in the torrid zone,

are covered with eternal snows, and below them the storm is seen to burst,

and the exploring traveler hears the thunder roll, and sees the lightnings

dart beneath his feet. Throughout the whole of the range of these extensive

mountains, as far as they have been explored, there is a certain boundary,

above which the snow never melts; which boundary, in the torrid zone, has

been ascertained to be fourteen thousand, six hundred feet, or nearly three

miles above the level of the sea.

The ascent to the plain of Quito, on which stands Chimborazo, Cotopaxi,

Pichincha, &c., is thus described by Don Juan de Ulloa:

“The ruggedness of the road from Taraguaga, leading up the mountain,

is not easily described. The declivity is so great, in some parts, that the

mules can scarcely keep their footing; and, in others, the acclivity is equally

difficult. The trouble of sending people before to mend the road, the pain

arising from the many falls and bruises, and the being constantly wet to the

skin, might be supported; but these inconveniences are augmented by the

sight of such frightful precipices and deep abysses, as excite in the mind

constant terror. The road, in some places, is so steep, and yet so narrow,

that the mules are obliged to slide down without making any use whatever

of their feet. On one side of the rider, in this situation, rises an eminence

of many hundred yards; and, on the other, is an abyss of equal depth; so

that, if he should give the least check to his mule, and destroy the equilibrium,

both must inevitably perish.

“Having traveled nine days in this manner, slowly winding along the

sides of the mountains, we began to find the whole country covered with a

hoar-frost; and a hut, in which we reposed, had ice in it. At length, after

a perilous journey of fifteen days, we arrived upon a plain, at the extremity

of which stands the city of Quito, the capital of one of the most charming

regions in the world. Here, in the center of the torrid zone, the heat is not

only very tolerable, but, in some places, the cold is even painful. Here the

inhabitants enjoy the temperature and advantages of perpetual spring; the

fields being constantly covered with verdure, and enameled with flowers of

the most lively colors. But although this beautiful region is more elevated

than any other country in the world, and it employs so many days of painful

journey in the ascent, it is itself overlooked by tremendous mountains, their

sides being covered with snow, while their summits are flaming with

12volcanoes. These mountains seem piled one upon the other, and to rise,

with great boldness, to an astonishing hight. However, at a determined

point above the surface of the sea, the congelation is found at the same hight

in all the mountains. Those parts which are not subject to a continual

frost, have here and there growing upon them a species of rush, resembling

the broom, but much softer and more flexible. Toward the extremity of the

part where the rush grows, and the cold begins to increase, is found a

vegetable with a round bulbous head. Higher still, the earth is bare of

vegetation, and seems covered with eternal snow. The most remarkable

of the Andes are the mountains of Chimborazo, Cotopaxi, and Pichincha.”

CHIMBORAZO.

This is the most lofty and majestic peak of the Andes, and has a circular

summit. It is twenty-two thousand feet, or more than four miles high. On

the shores of the ocean, after the long rains of winter, Chimborazo appears

like a cloud in the horizon. It detaches itself from the neighboring summits,

and raises its lofty head over the whole chain of the Andes. Travelers who

have approached the summits of Mont Blanc and Mont Rose, are alone

capable of feeling the effect of such vast, majestic, and solemn scenery.

The bulk of Chimborazo is so enormous, that the part which the eye

embraces at once, near the limit of the snows, is twenty-two thousand, nine

hundred and sixty-eight feet, or four miles and a third in breadth. The

extreme rarity of the strata of air across which the summits of the Andes

are seen, contributes greatly to the splendor of the snow and the magical

effect of its reflection. Under the tropics, at a hight of sixteen thousand,

four hundred feet, or upward of three miles, the azure vault of the heavens

appears of an indigo tint; while, in so pure and transparent an atmosphere,

the outlines of the mountains seem to detach themselves from the sky, and

produce an effect at once sublime, awful, and profoundly impressive.

With the exception of the loftiest of the Himalaya, in Asia, Chimborazo

is the highest known mountain in the world. Humboldt, Bonpland,

and Montufar, were persevering enough to approach within one thousand,

six hundred feet of the summit of this mighty king of mountains. Being

aided in their ascent by a train of volcanic rocks, destitute of snow, they

thus attained the amazing hight of nearly four miles above the level of the

sea; and the former of these naturalists is persuaded that they might have

reached the highest summit, had it not been for the intervention of a great

crevice, or gap, which they were unable to cross. They were, therefore,

obliged to descend, after experiencing great inconveniences and many

unpleasant sensations. For three or four days, even after their return into

13the plain, they were not free from sickness, and an uncomfortable feeling,

owing, as they suppose, to the vast proportion of oxygen in the atmosphere

above. Long before they reached the above surprising hight, they had

been abandoned by their guides, the Indians, who had taken alarm and

were fearful of their lives. So great was the fall of snow on their return,

that they could scarcely recognize each other, and they all suffered dreadfully

from the intenseness of the cold.

A great number of Spaniards formerly perished in crossing the vast and

dangerous deserts which lie on the declivity of Chimborazo; being now,

however, better acquainted with them, such misfortunes seldom occur,

especially as very few take this route, unless there be a prospect of calm

and serene weather.

COTOPAXI.

This mountain is the loftiest of those volcanoes of the Andes which, at

recent epochs, have undergone eruptions. Notwithstanding it lies near

the equator, its summits are covered with perpetual snows. The absolute

hight of Cotopaxi is eighteen thousand, eight hundred and seventy-six

feet, or three miles and a half; consequently it is two thousand, six

hundred and twenty-two feet, or half a mile, higher than Vesuvius

would be, were that mountain placed on the top of the peak of Teneriffe!

Cotopaxi is the most mischievous of the volcanoes in the vicinity of Quito,

and its explosions are the most frequent and disastrous. The masses of

scoriæ, and the pieces of rock, thrown out of this volcano, cover a surface

of several square leagues, and would form, were they heaped together, a

prodigious mountain. In 1738, the flames of Cotopaxi rose three thousand

feet, or upward of half a mile, above the brink of the crater. In 1744,

the roarings of this volcano were heard at the distance of six hundred

miles. On the fourth of April, 1768, the quantity of ashes ejected at the

mouth of Cotopaxi was so great, that it was dark till three in the afternoon.

The explosion which took place in 1803, was preceded by the sudden melting

of the snows which covered the mountain. For twenty years before no

smoke or vapor, that could be perceived, had issued from the crater; but in

a single night the subterraneous fires became so active, that at sunrise the

external walls of the cone, heated to a very considerable temperature,

appeared naked, and of the dark color which is peculiar to vitrified scoriæ.

“At the port of Guyaquil,” observes Humboldt, “fifty-two leagues distant

in a straight line from the crater, we heard, day and night, the noise of this

volcano, like continued discharges of a battery; and we distinguished these

tremendous sounds even on the Pacific ocean.”

14The form of Cotopaxi is the most beautiful and regular of the colossal

summits of the high Andes. It is a perfect cone, which, covered with a

perpetual layer of snow, shines with dazzling splendor at the setting of the

sun, and detaches itself in the most picturesque manner from the azure

vault above. This covering of snow conceals from the eye of the observer

even the smallest inequalities of the soil; no point of rock, no stony mass,

penetrating this coat of ice, or breaking the regularity of the figure of the

cone.

PICHINCHA.

Though celebrated for its great hight, Pichincha is three thousand,

eight hundred and forty-nine feet, or three-fourths of a mile, lower than

the perpendicular elevation of Cotopaxi. It was formerly a volcano; but

the mouth or crater on one of its sides is now covered with sand or

calcined matter, so that at present neither smoke nor ashes issue from it.

When it was ascended by Don George Juan and Don Antonio de Ulloa,

for the purpose of their astronomical observations, they found the cold on

the top of this mountain extremely intense, the wind very violent, and the

fog, or, in other words, the cloud, so thick, that objects at the distance of

six or eight paces were scarcely discernible. On the air becoming clear, by

the clouds descending nearer the earth, in such a manner as to surround

the mountain on all sides to a vast distance, these clouds afforded a lively

representation of the sea, in which the top of the mountain seemed to stand,

like an island in the center.

“With aspect mild, and elevated eye,

Behold him seated on a mount serene,

Above the fogs of sense, and passion’s storm:

All the black cares and tumults of this life,

Like harmless thunders, breaking at his feet.”—Young.

When the clouds descended, the astronomers heard the dreadful noise of

tempests, which discharged themselves from them on the adjacent country.

They saw the lightning issue from the clouds, and heard the thunder roll

far beneath them. While the lower parts were thus involved in tempests

of thunder and rain, they enjoyed a delightful serenity; the wind abated,

the sky cleared, and the enlivening rays of the sun moderated the severity

of the cold. But when the clouds rose, their density rendered respiration

difficult: snow and hail fell continually, and the winds returned with such

violence, that it was impossible to overcome the fear of being blown down

the precipices, or of being buried by the accumulation of ice and snow, or

by the enormous fragments of rocks which rolled around them. Every

15crevice in their hut was stopped, and though the hut was small, was crowded

with inhabitants, and several lamps were constantly burning, the cold was

so great, that each individual was obliged to have a chafing-dish of coals,

and several men were employed every morning in removing the snow which

had fallen during the night. Their feet were swollen, and they became so

tender and sensible, that walking was attended with extreme pain; their

hands also were covered with chilblains, and their lips were so swollen and

chapped, that every motion in speaking brought blood.

MOUNT ETNA.

“Now under sulphurous Cuma’s sea-bound coast,

And vast Sicilia, lies the shaggy breast

Of snowy Etna, nurse of endless frost,

The pillared prop of heaven, forever pressed:

Forth from whose sulph’rous caverns issuing rise

Pure liquid fountains of tempestuous fire,

Which vail in ruddy mists the noonday skies,

While wrapt in smoke the eddying flames aspire,

Or gleaming through the night with hideous roar,

Far o’er the redd’ning main huge rocky fragments pour.

“But he, Vulcanian monster, to the clouds

The fiercest, hottest inundations throws,

While, with the burthen of incumbent woods,

And Etna’s gloomy cliffs o’erwhelmed he glows.

There on his flinty bed outstretch’d he lies,

Whose pointed rock his tossing carcass wounds;

There with dismay he strikes beholding eyes,

Or frights the distant ear with horrid sounds.”—West.

Mount Etna, one of the most majestic of all the volcanoes, which the

ancients considered as one of the highest mountains in the world, and on

the summit of which they believed that Deucalion and Pyrrha sought

refuge, to save themselves from the universal deluge, is situated on the

plain of Catania, in Sicily.

Its elevation above the level of the sea has been estimated at ten thousand,

nine hundred and sixty-three feet, or upward of two miles. On clear days

it is distinctly seen from Valetta, the capital of Malta, a distance of one

hundred and fifty miles. It is incomparably the largest burning mountain

in Europe. From its sides other mountains arise, which, in different ages,

have been ejected in single masses from its enormous crater. The most

extensive lavas of Vesuvius do not exceed seven miles in length, while those

of Etna extend to fifteen, twenty, and some even to thirty miles. The

crater of Etna is seldom less than a mile in circuit, and sometimes is two or

16three miles; but the circumference of the Vesuvian crater is never more

than half a mile, even when widely distended, in its most destructive conflagrations.

And, lastly, the earthquakes occasioned by these adjacent

volcanoes, their eruptions, their showers of ignited stones, and the destruction

and desolation which they create, are severally proportionate to their

respective dimensions.

A journey up Etna is considered as an enterprise of importance, as well

from the difficulty of the route, as from the distance, it being thirty miles

from Catania to the summit of the mountain. Its gigantic bulk, its sublime

elevation, and the extensive, varied, and grand prospects which are presented

from its summit, have, however, induced the curious in every age to ascend

and examine it; and not a few have transmitted, through the press, the

observations which they have made during their arduous journey. From

its vast base it rises like a pyramid to the perpendicular hight of two miles,

by an acclivity nearly equal on all sides, forming with the horizon an angle

of about fifteen degrees, which becomes greater on approaching the crater;

but the inclination of the steepest part of the cone nowhere exceeds an

angle of forty-five degrees. This prodigious volcano may be compared to a

forge, which, in proportion to the violence of the fire, to the nature of the

fossil matters on which it acts, and of the gases which urge and set it in

17motion, produces, destroys, and reproduces, a variety of forms; and of this,

as of all active volcanoes, we may say in the language of Young,

“The dread volcano ministers to good;

Its smothered flames might undermine the world

Loud Etnas fulminate in love to man.”

The top of Etna being above the common region of vapors, the heavens,

at this elevation, appear with an unusual splendor. Brydone and his

company observed, as they ascended in the night, that the number of the

stars seemed to be infinitely increased, and the light of each was brighter

than usual. The whiteness of the milky way was like a pure flame which

spread across the heavens; and, with the naked eye, they could observe

clusters of stars which were invisible from below. They likewise noticed

several of those meteors called falling stars, which appeared as much

elevated here as when viewed from the plain beneath.

This single mountain contains an epitome of the different climates

throughout the world, presenting at once all the seasons of the year, and

all the varieties of produce. It is accordingly divided into three distinct

zones or regions, which may be distinguished as the torrid, temperate, and

frigid, but which are known by the names of the cultivated region, the

woody or temperate region, and the frigid or desert region. The former of

these extends through twelve miles of the ascent toward the summit, and

is almost incredibly abundant in pastures and fruit-trees of every description.

It is covered with towns, villages and monasteries; and the number of

inhabitants spread over its surface is estimated at one hundred and twenty

thousand. In ascending to the woody or temperate region, the scene

changes; it is a new climate, a new creation. Below, the heat is suffocating;

but here, the air is mild and fresh. The turf is covered with aromatic

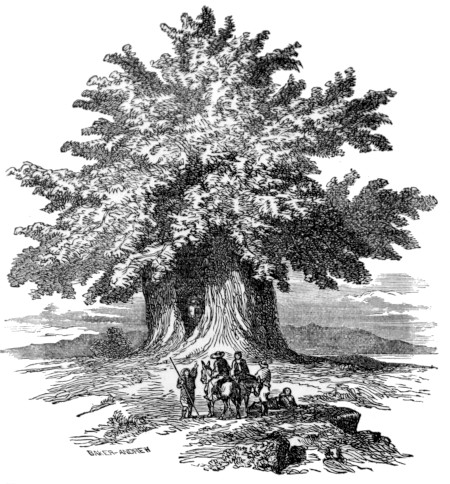

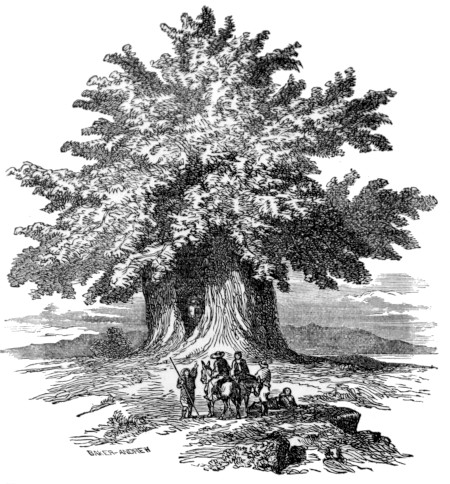

plants; and the gulfs, which formerly ejected torrents of fire, are changed

into woody valleys. Nothing can be more picturesque than this; the

inequality of the soil displaying every moment some variety of scene: here,

the ash and flowering thorns form domes of verdure; and there, the chestnut-trees

grow to an enormous size. The one called castagno de cento cavilli,

according to Brydone and Glover, has a circumference of two hundred and

four feet. Many of the oaks also are of a prodigious size. Mr. Swinburne

measured one which had a circumference of twenty-eight feet. The last,

or desert region, commences more than a mile above the level of the sea.

The lower part is covered with snow in winter only; but on the upper half

of this sterile district the snows continually lie.

18

THE “CASTANO DE CENTO CAVILLI,” OR GREAT CHESTNUT TREE OF MOUNT ETNA.

The cone of Etna is, in a right line, about a mile in ascent. The crater

is about a mile and a half in circumference; and from the inner part of

this, a column of smoke constantly rises; while the liquid fiery matter may

be seen rolling, rising and falling within. As to the vastness and beauty of

the prospect from the summit of Etna, all writers agree that it is probably

unsurpassed. M. Houel was there at sunrise, when the horizon was perfectly

clear, and the coast of Calabria, as seen in the distance, appeared to

the eye misty, and undistinguishable from the sea. The sky above was

specked with the light floating clouds that are so often seen in that delightful

climate before the rising of the sun; and in the calm silence all nature

seemed waiting the coming of the orb of day. And very soon the promise

thus given began to be fulfilled. In a short time a fiery radiance appeared

in the east. The fleecy clouds were tinged with purple; the atmosphere

19became strongly illuminated, and, reflecting the rays of the sun, seemed to

be filled with a bright refulgence of flame. Although the heavens were

thus enlightened, the sea still retained its dark azure, and the fields and

forests did not yet reflect the rays of the sun. The gradual rising of this

luminary, however, soon diffused light over the hills which lie below the

peak of Etna. This last stood like an island in the midst of the ocean, with

luminous points multiplying every moment around, and spreading over a

wider extent with the greatest rapidity. It was, he said, as if the world had

been observed suddenly to spring from the night of non-existence.

“Ere the rising sun

Shone o’er the deep, or ’mid the vault of night

The moon her silver lamp suspended; ere

The vales with springs were watered, or with groves

Of oak or pine the ancient hills were crowned;

Then the Great Spirit, whom his works adore,

Within his own deep essence viewed the forms,

The forms eternal of created things:

The radiant sun; the moon’s nocturnal lamp;

The mountains and the streams: the ample stores

Of earth, of heaven, of nature. From the first,

On that full scene his love divine he fixed,

His admiration. Till, in time complete,

What he admired and loved, his vital power

Unfolded into being. Hence the breath

Of life, informing each organic frame;

Hence the green earth, and wild resounding waves;

Hence light and shade, alternate; warmth and cold;

And bright autumnal skies, and vernal showers,

And all the fair variety of things.”—Akenside.

The most sublime object, however, which the summit of Etna presents, is

the immense mass of its own colossal body. Its upper region exhibits rough

and craggy cliffs, rising perpendicularly, fearful to the view, and surrounded

by an assemblage of fugitive clouds, to increase the wild variety of the scene.

Amid the multitude of woods in the middle or temperate region, are

numerous mountains, which, in any other situation, would appear of a

gigantic size, but which, compared to Etna, are mere mole-hills. Lastly,

the eye contemplates with admiration the lower region, the most extensive

of the three, adorned with elegant villas and castles, verdant hills and

flowery fields, and terminated by the extensive coast, where to the south

stands the beautiful city of Catania, to which the waves of the neighboring

sea serve as a mirror.

Etna has been celebrated as a volcano from the remotest antiquity.

20Eruptions are recorded by Diodorus Siculus, as having happened five

hundred years before the Trojan war, or sixteen hundred and ninety-three

years before the Christian era.

“Etna roars with dreadful ruins nigh,

Now hurls a bursting cloud of cinders high,

Involved in smoky whirlwinds to the sky;

With loud displosion to the starry frame,

Shoots fiery globes, and furious floods of flame:

Now from her bellowing caverns burst away

Vast piles of melted rocks in open day.

Her shattered entrails wide the mountain throws,

And deep as hell her flaming center glows.”—Warton.

In 1669, the torrent of burning lava inundated a space fourteen miles in

length, and four in breadth, burying beneath it part of Catania, till at length

it precipitated itself into the sea. For several months before the lava broke

out, the old mouth, or great crater of the summit, was observed to send

forth much smoke and flame, and the top had fallen in, so that the mountain

was much lowered.

Eighteen days before, the sky was very thick and dark, with thunder,

lightning, frequent concussions of the earth, and dreadful subterraneous

bellowings. On the eleventh of March, about sunset, an immense gulf

opened in the mountain, into which when stones were thrown, they could

not be heard to strike the bottom. Ignited rocks, fifteen feet in length,

were hurled to the distance of a mile; while others of a smaller size were

carried three miles. During the night, the red-hot lava burst out of a

vineyard twenty miles below the great crater, and ascended into the air to a

considerable hight. In its course, it destroyed five thousand habitations,

and filled up a lake several fathoms deep. It shortly after reached Catania,

rose over the walls, whence it ran for a considerable length into the sea,

forming a safe and beautiful harbor, which was, however, soon filled up by

a similar torrent of inflamed matter. This is the stream, the hideous

deformity of which, devoid of vegetation, still disfigures the south and

western borders of Catania, and on which part of the noble modern city is

built.

The showers of scoriæ and sand which, after a lapse of two days, followed

this eruption, formed a mountain called Monte Rosso, having a base of

about two miles, and a perpendicular hight of seven hundred and fifty feet.

On the twenty-fifth, the whole mountain, even to the most elevated peak,

was agitated by a tremendous earthquake. The highest crater of Etna,

which was one of the loftiest parts of the mountain, then sunk into the

21volcanic gulf, and in the place which it had occupied, there now appeared

nothing but a wide gulf, more than a mile in extent, from which issued

enormous quantities of smoke, ashes and stones.

In 1809, twelve new craters opened about half-way down the mountain,

and threw out rivers of burning lava, by which several estates were covered

to the depth of thirty or forty feet; and during three or four successive

nights, a very large river of red-hot lava was distinctly seen, in its whole

extent, running down from the mountain.

In 1811, several mouths opened on the eastern side of the mountain:

being nearly in the same line, and at equal distances, they presented to the

view a striking spectacle; torrents of burning matter, discharged with the

greatest force from the interior of the volcano, illuminated the horizon to a

great extent. An immense quantity of matter, which was driven to considerable

distances, was discharged from these apertures, the largest of which

continued for several months to emit torrents of fire. Even at the time

when it had the appearance of being choked, there suddenly issued from it

clouds of ashes, which descended, in the form of rain, on the city of Catania

and its environs, as well as on the fields situated at a very considerable

distance. A roaring, resembling that of a sea in the midst of a tempest,

was heard to proceed from the interior of the mountain; and this sound,

accompanied from time to time by dreadful explosions, resembling thunder,

reëchoed through the valleys, and spread terror on every side.

MOUNT VESUVIUS.

“The fluid lake that works below,

Bitumen, sulphur, salt, and iron scum,

Heaves up its boiling tide. The lab’ring mount

Is torn with agonizing throes. At once,

Forth from its sides disparted, blazing pours

A mighty river; burning in prone waves,

That glimmer through the night, to yonder plain.

Divided there, a hundred torrent streams,

Each plowing up its bed, roll dreadful on,

Resistless. Villages, and woods, and rocks,

Fall flat before their sweep. The region round,

Where myrtle-walks and groves of golden fruit

Rose fair; where harvest wav’d in all its pride;

And where the vineyard spread its purple store,

Maturing into nectar; now despoiled

Of herb, leaf, fruit and flower, from end to end

Lies buried under fire, a glowing sea!”—Mallet.

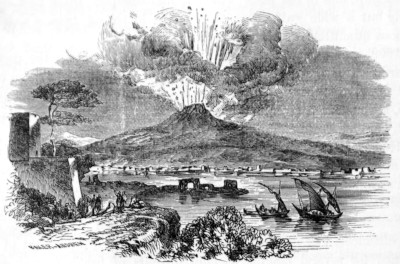

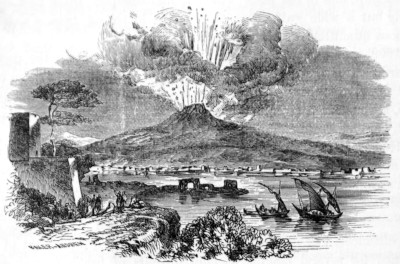

This celebrated volcano, which has for so many ages attracted the attention

of mankind, and the desolating eruptions of which have been so often

22and so fatally experienced, is distant, in an eastern direction, about seven

miles from Naples. It rises, insulated, upon a vast and well cultivated

plain, presenting two summits on the same base, in which particular it

resembles Mount Parnassus. One of these, La Somma, is generally agreed

to have been the Vesuvius of Strabo and the ancients; the other, having the

greatest elevation, is the mouth of the volcano, which almost constantly

emits smoke. Its hight above the level of the sea, is thirty-nine hundred

feet, and it may be ascended by three different routes, which are all

very steep and difficult, from the conical form of the mountain, and the

loose ashes which slip from under the feet: still, from the base to the

summit, the distance is not more than three Italian miles. The circumference

of the platform on the top, is five thousand and twenty-four feet, or

nearly a mile. Thence may be seen Portici, Capræa, Ischia, Pausilippo,

and the whole coast of the gulf of Naples, bordered with orange-trees: the

prospect is that of Paradise seen from the infernal regions.

On approaching the mountain, its aspect does not convey any impression

of terror, nor is it gloomy, being cultivated for more than two-thirds of its

hight, and having its brown top alone barren. There all verdure ceases;

yet, when it appears covered with clouds, which sometimes encompass its

middle only, this circumstance rather adds to than detracts from the magnificence

of the spectacle. Upon the lavas which the volcano long ago

ejected, and which, like great furrows, extend into the plain and to the sea,

are built houses, villages and towns. Gardens, vineyards and cultivated

fields surround them; but a sentiment of sorrow, blended with apprehensions

23about the future, arises on the recollection that, beneath a soil so

fruitful and so smiling, lie edifices, gardens and whole towns swallowed up.

Portici rests upon Herculaneum; its environs upon Resina; and at a little

distance is Pompeii, in the streets of which, after more than seventeen

centuries of non-existence, the astonished traveler now walks. After a long

interval of repose, in the first year of the reign of Titus, (the seventy-ninth

of the Christian era,) the volcano suddenly broke out, ejecting thick clouds

of ashes and pumice-stones, beneath which Herculaneum, Stabia and Pompeii

were completely buried. This eruption was fatal to the elder Pliny, the

historian, who fell a victim to his humanity and love of science. Even at

this day, in speaking of Vesuvius, the remembrance of his untimely death

excites a melancholy regret. All the coast to the east of the gulf of Naples

was, on the above occasion, ravaged and destroyed, presenting nothing but

a long succession of ejected matters from Herculaneum to Stabia. The

destruction did not extend to the western part, but stopped at Naples, which

suffered comparatively little.

Thirty-eight eruptions of Vesuvius are recorded in history up to the year

1806. That of 1779, has been described by Sir William Hamilton, as

among the most remarkable, from its extraordinary and terrific appearance.

During the whole of July, the mountain was in a state of considerable

fermentation, subterraneous explosions and rumbling noises being heard,

and quantities of smoke thrown up with great violence, sometimes with red-hot

stones, scoriæ, and ashes. On the fifth of August, the volcano was

greatly agitated, a white sulphurous smoke, apparently four times the hight

and size of the volcano itself, issuing from the crater, at the same time that

vast quantities of stones, &c., were thrown up to the supposed hight of two

thousand feet. The liquid lava, having cleared the rim of the crater, flowed

down the sides of the mountain to the distance of four miles. The air was

darkened by showers of reddish ashes, blended with long filaments of a

vitrified matter resembling glass.

On the seventh, at midnight, a fountain of fire shot up from the crater to

an incredible hight, casting so bright a light, that the smallest objects were

clearly distinguishable at any place within six miles of the volcano. On the

following evening, after a tremendous explosion, which broke the windows

of the houses at Portici, another fountain of liquid fire rose to the surprising

hight of ten thousand feet, (nearly two miles,) while puffs of the blackest

smoke accompanied the red-hot lava, interrupting its splendid brightness

here and there by patches of the darkest hue. The lava was partly directed

by the wind toward Ottaiano, on which so thick a shower of ashes, blended

with vast pieces of scoriæ, fell, that had it been of longer continuance, that

24town would have shared the fate of Pompeii. It took fire in several places;

and had there been much wind, the inhabitants would have been burned in

their houses, it being impossible for them to stir out. To add to the horror

of the scene, incessant volcanic lightning darted through the black cloud

that surrounded them, while the sulphureous smell and heat would scarcely

allow them to draw their breath. In this dreadful state they remained

nearly half an hour. The remaining part of the lava, still red-hot and

liquid, fell on the top of Vesuvius, and covered its whole cone, together with

that of La Somma, and the valley between them, thus forming one complete

body of fire, which could not be less than two miles and a half in breadth,

and casting a heat to the distance of at least six miles around.

The eruption of 1794 is accurately described by the above writer; but

has not an equal degree of interest with the one cited above. We subjoin

a few particulars, among which is a circumstance well deserving notice, as

it leads to an estimate of the degree of heat in volcanoes. Sir William says

that although the town of Torre del Greco was instantly surrounded with

red-hot lava, the inhabitants saved themselves by coming out of the tops of

their houses on the following day. It is evident, observes Mr. Kirwan, that

if this lava had been hot enough to melt even the most fusible stones, these

persons must have been suffocated.

This eruption happened on the fifteenth of June, at ten o’clock at night,

and was announced by a shock of an earthquake, which was distinctly felt

at Naples. At the same moment a fountain of bright fire, attended with a

very black smoke and a loud report, was seen to issue, and rise to a considerable

hight, from about the middle of the cone of Vesuvius. It was

hastily succeeded by other fountains, fifteen of which were counted, all in a

direct line, tending for the space of about a mile and a half downward,

toward the towns of Resina and Torre del Greco. This fiery scene, this

great operation of nature, was accompanied by the loudest thunder, the

incessant reports of which, like those of a numerous heavy artillery, were

attended by a continued hollow murmur, similar to that of the roaring of

the ocean during a violent storm. Another blowing noise resembled that

of the ascent of a large flight of rockets. The houses at Naples were for

several hours in a constant tremor, the doors and windows shaking and

rattling incessantly, and the bells ringing. At this awful moment the sky,

from a bright full moon and starlight, became obscured; the moon seemed

eclipsed, and was soon lost in obscurity. The murmur of the prayers and

lamentations of a numerous population, forming various processions, and

parading the streets, added to the horrors of the scene.

On the following day a new mouth was opened on the opposite side of the

25mountain, facing the town of Ottaiano: from this aperture a considerable

stream of lava issued, and ran with great velocity through a wood, which

it burnt; but it stopped, after having run about three miles in a few hours,

before it reached the vineyards and cultivated lands. The lava which had

flowed from several new mouths on the south side of the mountain, reached

the sea into which it ran, after having overwhelmed, burnt and destroyed

the greater part of Torre del Greco, through the center of which it took its

course. This town contained about eighteen thousand inhabitants, all of

whom escaped, with the exception of about fifteen, who through age or

infirmity, were overwhelmed in their houses by the lava. Its rapid progress

was such, that their goods and effects were entirely abandoned.

It was ascertained some time after, that a considerable part of the crater

had fallen in, so as to have given a great extension to the mouth of Vesuvius,

which was conjectured to be nearly two miles in circumference. This

sinking of the crater was chiefly on the west side, opposite Naples, and, in all

probability, occurred early in the morning of the eighteenth, when a violent

shock of an earthquake was felt at Resina, and other places situated at the

foot of the volcano. The clouds of smoke which issued from the now

widely extended mouth of Vesuvius, were of such a density as to appear to

force their passage with the utmost difficulty. One cloud heaped itself on

another, and, succeeding each other incessantly, they formed in a few hours

such a gigantic and elevated column, of the darkest hue, over the mountain,

as seemed to threaten Naples with immediate destruction, it having at one

time been bent over the city, and appearing to be much too massive and

ponderous to remain long suspended in the air.

From the above time, till 1804, Vesuvius remained in a state of almost

constant tranquillity. Symptoms of a fresh eruption had manifested themselves

for several months, when at length on the night of the eleventh of

August, a deep roaring was heard at the hermitage of Salvador, and the

places adjacent to the mountain, accompanied by shocks of an earthquake,

which were sensibly felt at Resina. On the following morning, at noon, a

thick black smoke rose from the mouth of the crater, which, dilating

prodigiously, covered the whole volcano. In the evening, loud explosions

were heard; and at Naples a column of fire was seen to rise from the

aperture, carrying up stones in a state of complete ignition, which fell

again into the crater. The noise by which these igneous explosions were

accompanied, resembled the roaring of the most dreadful tempest and the

whistling of the most furious winds; while the celerity with which the

substances were ejected was such, that the first emission had not terminated

when it was succeeded by a second. Small monticules were at this time

26formed of a fluid matter, resembling a vitreous paste of a red color, which

flowed from the mouth of the crater; and these became more considerable

in proportion as the matter accumulated.

In this state the eruption continued for several days, the fire being equally

intense, with frequent and dreadful noises. On the twenty-eighth, amid these

fearful symptoms, another aperture, ejecting fire and stones, situated behind

the crater, was seen from Naples. The burning mass of lava which escaped

from the crater on the following day, was distinguished from Torre del

Greco, having the appearance of a vitreous fluid, and advancing toward

the base of the mountain between the south and south-west. It reached the

base on the thirtieth, having flowed from the aperture, in less than twenty-four

hours, a distance of three thousand and fifty-three feet, while its mean

breadth appeared to be about three hundred and fifty, but at the base, eight

hundred and sixty feet. In its course it divided into four branches, and

finally reached a spot called the Guide’s Retreat. Its entire progress to

this point was more than a mile, so that, taking a mean proportion, this

lava flowed at the rate of eightyeighty-six feet an hour.

At the time of this eruption, Kotzebue was at Naples. Vesuvius lay

opposite to his window, and when it was dark he could clearly perceive in

what manner the masses of fire rolled down the mountain. As long as any

glimmering of light remained, that part of the mountain was to be seen on

the declivity of which the lava formed a straight but oblique line. As soon,

however, as it was perfectly dark, and the mountain itself had vanished

from the eye, it seemed as if a comet with a long tail stood in the sky.

The spectacle was awful and grand!

Kotzebue ascended the mountain on the morning succeeding the opening

of a new gulf, and approached the crater as nearly as prudence would allow.

From its center ascended the sulphurous yellow cone which the eruption of

this year had formed: on the other side, a thick smoke perpetually arose

from the abyss opened during the preceding night. The side of the crater

opposite to him, which rose considerably higher than that on which he stood,

afforded a singular aspect; for it was covered with little pillars of smoke,

which burst forth from it, and had some resemblance to extinguished lights.

The air over the crater was actually embodied, and was clearly to be seen

in a tremulous motion. Below, the volcano boiled and roared dreadfully,

like the most violent hurricane; but occasionally a sudden deadly stillness

ensued for some moments, after which the roaring renewed with double

vehemence, and the smoke burst forth in thicker and blacker clouds. It

was, he observes, as if the spirit of the mountain had suddenly tried to

stop the gulf, while the flames indignantly refused to endure the confinement.

27It is remarkable, that the great eruption of 1805, happened on the twelfth

of August, within a day of that of the preceding year. Subterraneous

noises had been previously heard, and a general apprehension of some

violent commotion prevailing, the inhabitants of Torre del Greco and

Annunciada had left their homes, through the apprehension of a shower of

fire and ashes, similar to that which buried Pompeii. The stream of lava

took the same course with that of 1794, described above, one of the arms

following the direction of the great road, and rolling toward the sea. The

stream soon divided again, and spreading itself with an increased celerity,

swept away many houses and the finest plantations. The other branch, at

first, took the direction of Portici, which was threatened; but turning, and

joining the preceding one, formed a sort of islet of boiling lava in the

middle, both ending in the sea, and composing a promontory of volcanic

matters. In the space of twenty minutes the whole extent of ground

which the lava occupied was on fire, offering a terrible yet singular spectacle,

as the burning trees presented the aspect of white flames, in contrast with

those of the volcanic matters, which were red. The lava swept along with

it enormous masses of whatever occurred in its course, and, on its reaching

the sea, nothing was to be seen or heard for a great extent of shore, beside

the boiling and hissing arising from the conflict of the water and fire.

It remains now to introduce a slight notice of the eruption of 1806,

which, without any sensible indication, took place on the evening of the thirty-first

of May, when a bright flame rose from the mountain to the hight of

about six hundred feet, sinking and rising alternately, and affording so clear

a light, that a letter might have been read at the distance of a league

around the mountain. On the following morning, without any earthquake

preceding, as had been customary, the volcano began to eject inflamed

substances from three new mouths, pretty near to each other, and about six

hundred and fifty feet from the summit. The lava took the direction of

Torre del Greco and Annunciada, approaching Portici, on the road leading

from Naples to Pompeii. Throughout the whole of the second of June, a

noise was heard, resembling that of two armies engaged, when the discharges

of artillery and musketry are very brisk. The current of lava now resembled

a wall of glass in a state of fusion, sparks and flashes issuing from it

from time to time, with a powerful detonation. Vines, trees, houses—whatever

objects, in short, it encountered on its way, were instantly overthrown

or destroyed. In one part, where it met with the resistance of a

wall, it formed a cascade of fire. In a few days Portici, Resina, and Torre

del Greco, were covered with ashes thrown out by the volcano; and on the

ninth, the two former places were deluged with a thick black rain, consisting

28of a species of mud filled with sulphurous particles. On the first of July,

the ancient crater had wholly disappeareddisappeared, being filled with ashes and lava,

and a new one was formed in the eastern part of the mountain, about six

hundred feet in depth, and having about the same width at the opening.

Several persons, on the above day, descended about half-way down this new

mouth, and remained half an hour very near the flames, admiring the

spectacle presented by the liquid lava, which bubbled up at the bottom of

the crater, like the fused matter in a glass-house. This eruption continued

until September, made great ravages, and was considered as one of the

most terrible that had occurred in the memory of the inhabitants.

MOUNT HECLA.

“Still pressing on beneath Tornea’s lake,

And Hecla flaming through a waste of snow,

And farthest Greenland, to the pole itself,

Where, falling gradual, life at length goes out,

The Muse expands her solitary flight;

And hov’ring o’er the wide stupendous scene,

Beholds new scenes beneath another sky.

Throned in his palace of cerulean ice,

Here Winter holds his unrejoicing court,

And through his airy hall the loud misrule

Of driving tempest is forever heard;

Here the grim tyrant meditates his wrath;

Here arms his winds with all-subduing frost,

Molds his fierce hail, and treasures up his snows.”

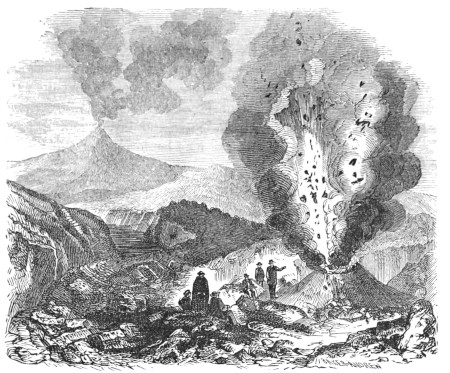

On proceeding along the southern coast of Iceland, and at an inconsiderable

distance from Skalholt, Mount Hecla, with its three summits, presents

itself to the view. Its hight is five thousand feet, or nearly a mile above

the level of the sea. It is not a promontory, but lies about four miles

inland. It is neither so elevated nor so picturesque as several of the

surrounding Icelandic mountains; but has been more noticed than many

other volcanoes of an equal extent, partly through the frequency of its

eruptions, and partly from its situation, which exposes it to the view of

many ships sailing to Greenland and North America. The surrounding

territory has been so devastated by these eruptions, that it has been deserted.

“Vast regions dreary, bleak and bare!

There on an icy mountain’s hight,

Seen only by the moon’s pale light

Stern Winter rears his giant form,

His robe a mist, his life a storm:

His frown the shiv’ring nations fly,

And, hid for half the year, in smoky caverns lie.”

29

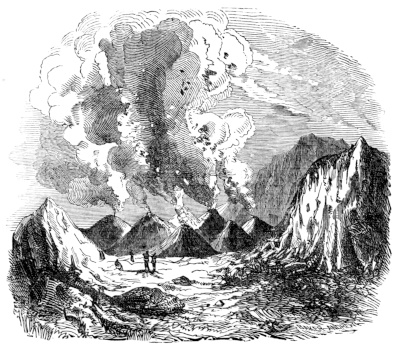

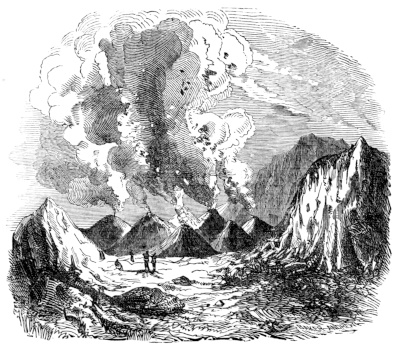

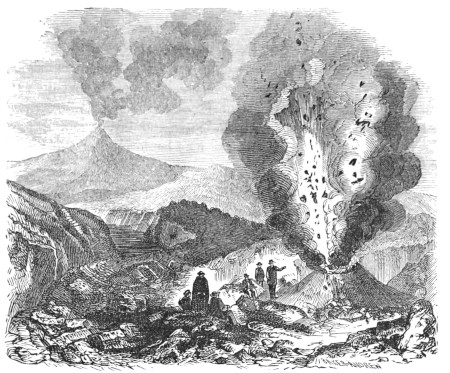

MOUNT HECLA AND THE GEYSERS.

The natives assert that it is impossible to ascend the mountain, on

account of the great number of dangerous bogs, which, according to them,

are constantly emitting sulphurous flames and exhaling smoke; while the

more elevated summit in the center is covered with boiling springs and

large craters, which continually propel fire and smoke. To the south and

west the environs present the most desolating results of frequent eruptions,

the finest part of the territory being covered by torrents of melted stone,

sand, ashes, and other volcanic matter; notwithstanding which, between the

sinuosities of the lava in different parts, some portion of meadows, walls

and broken hedges may be observed. The devastation is still greater on

the north and east sides, which present dreadful traces of the ruin of the

country and its habitations. Neither plants nor grass are to be met with to

the extent of two leagues round the mountain, in consequence of the soil

being covered with stones and lava; and in some parts, where the subterraneous

fire has broken out a second time, or where the matter which was not

entirely consumed has again become ignited, the fire has contributed to

form small red and black hillocks and eminences, from scoriæ, pumice-stones

and ashes. The nearer the mountain the larger are these hillocks,

and there are some of them, the summits of which form a circular hollow,

whence the subterraneous fire ejects the matter. On approaching Hecla

30the ground becomes almost impassable, particularly near the higher branches

of lava thrown from the volcano. Round the latter is a mountain of lava,

consisting of large fused stones, from forty to seventy feet high, and in the

form of a rampart or wall. These stones are detached, and chiefly covered

with moss; while between them are very deep holes, so that the ascent on

the western side requires great circumspection. The rocks are completely

reduced to pumice, dispersed in thin horizontal layers, and fractured in

every direction, from which some idea may be formed of the intensity of

the fire that has acted on them.

“There Winter, armed with terrors here unknown,

Sits absolute on his unshaken throne;

Piles up his stores amidst the frozen waste,

And bids the mountains he has built stand fast;

Beckons the legions of his storms away

From happier scenes to make the land a prey;

Proclaims the soil a conquest he has won,

And scorns to share it with the distant sun.”

Sir Joseph Banks, Dr. Solander, Dr. James Lind, of Edinburgh, and Dr.

Van Troil, a Swede, were the earliest adventurous travelers who ascended

to the summit of Mount Hecla. This was in 1772; and the attempt was

facilitated by a preceding eruption in 1766, which had greatly diminished

the steepness and difficulty of the ascent. On their first landing, they found

a tract of land sixty or seventy miles in extent, entirely ruined by lava,

which appeared to have been in a state of complete liquefaction. To accomplish

their undertaking, they had to travel from three hundred to three

hundred and sixty miles over uninterrupted tracts of lava. In ascending,

they were obliged to quit their horses at the first opening from which the

fire had burst: a spot, which they describe as presenting lofty glazed walls

and high glazed cliffs, differing from anything they had ever seen before.

At another opening above, they fancied they discerned the effects of boiling

water; and not far from thence, the mountain, with the exception of some

bare spots, was covered with snow. The difference of aspect they soon

perceived to be occasioned by the hot vapor ascending from the mountain.

The higher they proceeded, the larger these spots became; and, about two

hundred yards below the summit, a hole about a yard and a half in diameter,

was observed, whence issued so hot a stream, that they could not

measure the degree of heat with a thermometer. The cold now began to

be very intense. Fahrenheit’s thermometer, which at the foot of the mountain

was at fifty-four degrees, fell to twenty-four degrees; while the wind

became so violent, that they were sometimes obliged to lie down, from a

31dread of being blown into the most dreadful precipices. On the summit

itself they experienced, at one and the same time, a high degree of heat and

cold; for, in the air, Fahrenheit’s thermometer constantly stood at twenty-four

degrees, but when placed on the ground, it rose to one hundred and

fifty-three degrees.

Messrs. Olafsen and Povelsen, two naturalists, whose travels in Iceland

were undertaken by order of his Danish majesty, after a fatiguing journey

up several small slopes, which occurred at intervals, and seven of which

they had to pass, at length reached the summit of Mount Hecla at midnight.

It was as light as at noonday, so that they had a view of an immense extent,

but could perceive nothing but ice; neither fissures, streams of water,

boiling springs, smoke, nor fire, were apparent. They surveyed the glaciers

in the eastern part, and in the distance saw the high and square mountain

of Hærdabreid, an ancient volcano, which appeared like a large castle.

Sir G. S. Mackenzie, in his travels in Iceland, ascended Mount Hecla;

and from his account we extract the following interesting particulars.

In proceeding to the southern extremity of the mountain, he descended, by

a dangerous path, into a valley, having a small lake in one corner, and the