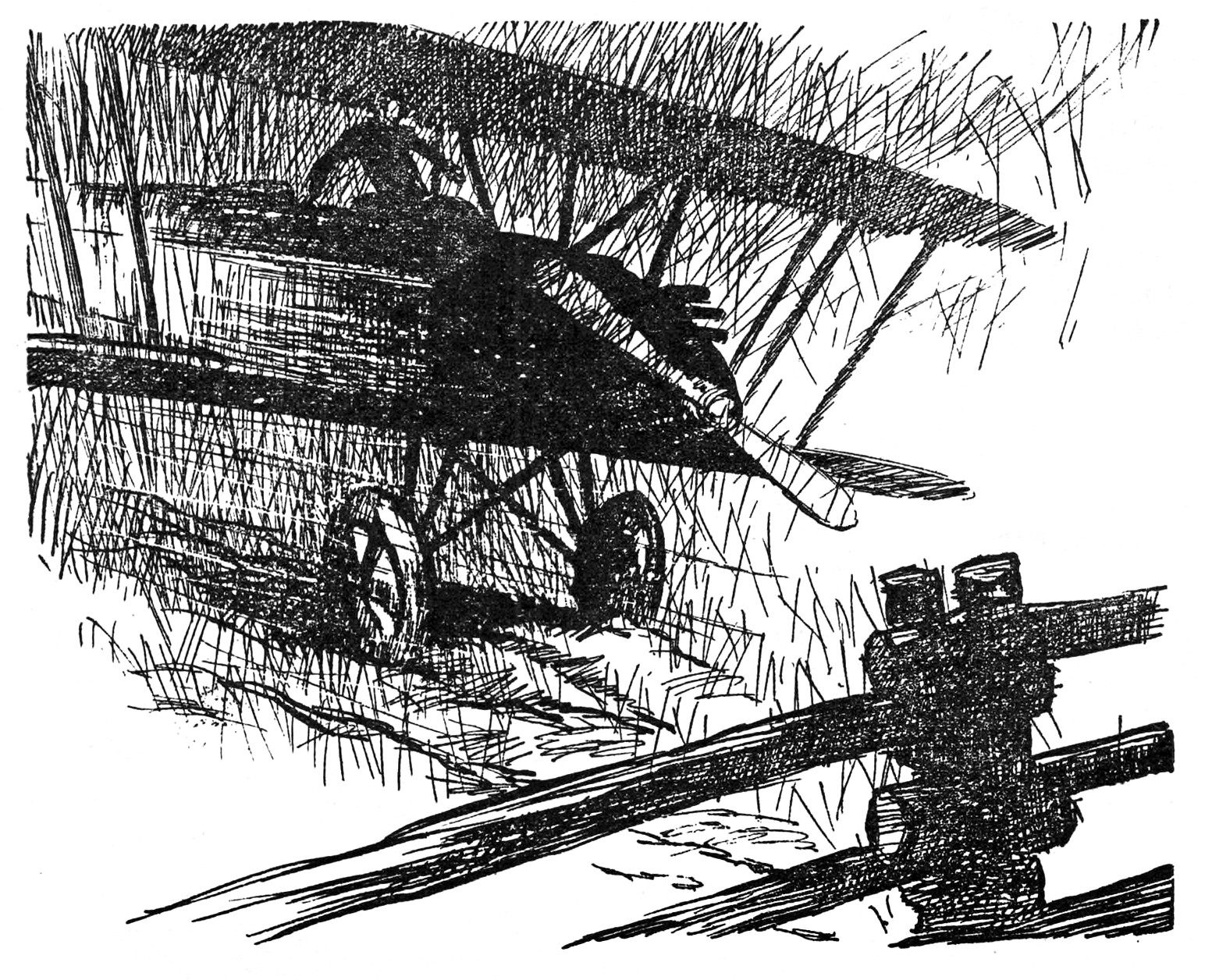

A biplane on the further side of five years, but spruce enough, considering her age, stood silent at the edge of a New Jersey meadow, while a thin, sandy-haired young man in dungarees ministered to her numerous wants with a pair of pliers.

He was busy on the interwing wires, methodically tightening or loosening turnbuckles according to his idea of rigging. From this work he looked up with a nod when a rickety flivver rolled up to the edge of the field and his partner, “Beak” Becket, got out.

Though Beak had been to town merely to get some cigarettes and to transact a small business matter, he wore the full regalia of a pilot—leather coat, whipcord knickers and glistening Cordovan puttees. On his head, accentuating the eagle-like curve of his brown nose, was a new leather helmet, with tabs unfastened. His eyes were habitually fierce, also like an eagle’s, and now they seemed fiercer than usual to Jerry Tabor.

When the flivver driver had been paid, Beak took off his fine jacket, lit a cigarette and strolled over to the plane. With the removal of his coat, Beak had also removed something else—something less tangible, perhaps, but none the less apparent. For the coat had concealed the fact that Beak’s whipcord knickers fitted him a bit too snugly and that his stomach ran his chest a close race in the matter of prominence.

Beak Becket glowered at his partner. He kicked a chock vigorously out of the way. Then he tested the tension of one of the wires with a grip of his hand and scowled at the young man in dungarees. Jerry looked up with a certain apprehension in his face.

“You get some of the strain off those lift wires, and do it in a hurry, too,” Beak said petulantly. “Don’t you know yet that lift wires should be slack when she rests on the ground?”

“That wire was so loose it vibrated like a harp cord when I test-hopped her,” Jerry Tabot explained mildly. “I’ll take some out, Beak, but―”

“You test-hopped her!” Beak repeated, in a tone of derision. “What does a wing walker know about test-hopping? About as much as a fish knows about ice skating. You leave test-hopping to me, my boy.”

Jerry got red under his sunburn.

“If I’m not a pilot as well as a wing walker, you got money under false pretenses, Beak,” he answered steadily.

“Made his solo three months ago—and thinks he can tell me when a ship is rigged right!” the older aviator remarked caustically to some unseen spectator. “He’ll be claiming he invented planes in another three months.”

Jerry stirred, as if under the lash of a whip. Nevertheless, he showed a placating grin. It was always possible that Beak had run into some particularly bad liquor and that he could be kidded out of his fit of temper.

“What’s the matter, Beak?” Jerry inquired. “Did another race horse sit down on you? You ought to stick to flying. Betting on races is risky.”

“When I need your advice, kid, it’ll be because everybody else is dead!” Beak snapped. He ignored the smile. “You slack off that wire, d’you hear? We’re going to hop out of this Godforsaken neighborhood right away. It’s as full of barnstorming planes as a dog is of fleas.”

Jerry looked at the senior partner in surprise.

“I thought we’d been doing pretty good business, myself, Beak,” he commented.

“Don’t think. Work!” Beak meditated, scowling at his puttees. “I’m getting pretty low down, I am,” he said aloud. “Me, Beak Becket, one of the pioneers in the flying game—one of the few of ’em left—being given orders by my own mechanic and wing walker! I’ve flown before kings and presidents and shaken hands with ’em afterward; I’ve thrilled millions with my daring— and now a kid I picked up and learned to fly tells me where I get off.”

“I understood we were partners, Beak, I having supplied the money for this ship and you having taught me to fly and having the experience,” Jerry said steadily.

“He thinks we been doing pretty good business, he does,” Beak went on, addressing the air. “Since when, even if they are partners, did a dirty-faced, wing-walking crowd catcher stand knee high to a flying man?”

Jerry Tabor gripped his pliers tightly, then slipped them into a pocket and turned to face the other man.

“Beak, you and I don’t seem to be hitting it off as well as we might, lately,” he said. “I reckon half of it’s my fault, anyhow.”

“You’re right; half of it and more, kid. Telling a man like me, one of the best-known pilots in the world, where to get off because I venture to say that flying wire’s too taut!”

Jerry sighed.

“And throwing it in my face all the time that it was his money that bought the ship!” Beak added.

Jerry unbuttoned the dungaree coat.

“That does it, Beak,” he said. “I don’t mind being your mechanic and wing walker and just getting a chance at the stock once in a while when the crowd’s thin or you don’t feel like flying, but all this talk besides is too much. It don’t help my wing walking any. I nearly lost my grip yesterday. I guess it’s about time we put some air between us.”

Beak blinked at this. There was something decisive about the way Jerry Tabor took off his work clothes. Beak disliked work clothes, himself, and the sight of his partner taking them off raised forebodings. He thought quickly and then spat out his cigarette.

“That suits me fine,” he growled. “The old man’s taught you to fly; he ain’t much more use to you. Go ahead, Jerry; I won’t stand in your way.”

Jerry was a bit staggered at Beak’s ready acceptance. Nevertheless, he remained determined.

“How about the ship and the ’chute?” he asked. “Will you buy me out or will I buy you?”

“You know damn well you’ve got me at a disadvantage, owing to—reverses,” said Beak with dignity. “I can’t buy you out, but you can buy me. I value my half of the ship at five hundred, and my half of the ’chute at fifty. Five hundred and fifty’s the amount.”

Jerry Tabor opened his eyes wide. There was a gleam of anger in them. “Why the ship only cost seven fifty when I—we—bought it six months ago!”

“That was before I had it lined up right and the wings partly recovered,” Beak answered coldly.

“But—it was I that did most of the work on her!” Jerry protested. He was holding himself in with a great effort.

“And it was I that did most of the flying. You think you can freeze me out of this ship because you have a little ready cash tucked away? Guess again and guess better!”

“I can’t pay it,” Jerry said, dispirited. “I haven’t got that much.”

“That’s not my fault,” said Beak. “If you want to go, go ahead, and I’ll pay you for your share of the ship—when I can.”

He looked at Jerry keenly. Jerry looked at the plane.

“Where this ship goes—that’s my post-office address,” Jerry declared emphatically.

“All right.” Beak cinched up his flying helmet. “We hop out of here right now, then, toward some place where the people appreciate a pilot like Beak Becket.”

For a moment Jerry Tabor hesitated on the verge of rebellion. Things had been getting worse and worse. But the man before him was Beak Becket, a pilot of whose exploits he had read when he was still in school. And Beak had taught him to fly. The money Jerry had paid—money won by hard work in an automobile factory—seemed little compared to the fact that Beak had made him a pilot. True, Beak had also made him a wing walker, a mechanic and a general errand boy, but allowances must be made, Jerry felt, for a godlike creature like Beak. Nevertheless Beak, though only thirty-eight, often acted like a querulous old man of seventy. The air—or something—had taken its toll of Beak.

“I’ll get ready,” Jerry decided. He glanced at the sun. “How far we traveling? It’s a bit late for a long hop.”

“Give me some more orders!” snapped Beak. “We’re going to hit it for Massachusetts—Pittsfield way, if you don’t mind. If you do mind, we’re going to hit it that way just the same. Get busy!”

As a hero, Beak had become somewhat shopworn as a partner he was a tyrant, but Jerry got busy nevertheless. While he owned half the ship he would not leave her. He ached for the time when he would be his own master, with no old man of the air to ride him. But Beak had made it plain that that time was still far off.

At a word from the pilot Jerry swung the prop and then, while Beak warmed the ship up, he lashed an extra wheel and a five-gallon gas can to the wing beside the fuselage and packed their two suitcases in the front cockpit. As he picked up the parachute pack to stow that, Beak throttled down the roaring motor to speak to him.

“You put that ’chute on,” Beak commanded. “I may want you to do a jump to let 'em know we’ve come—if we hit a likely-looking town.”

It was a seat-pack type ’chute and as comfortable to sit on as the seat. Silently Jerry strapped on the heavy harness, put the chocks and a few other miscellaneous articles comprising their scanty equipment on board and clambered into the front cockpit. There wasn’t much room in there for him, for not only was the baggage bulky, but the ship still had the stick and rudder bar dual controls connected up. Beak’s last job at this field had been helping an old war pilot try to get back the feel of the air at thirty dollars an hour.

“Keep that duffel clear of the controls and check me on the chart,” Beak shouted, passing Jerry a dirty map of the southern New England states.

Jerry nodded and as they taxied out on the field he took a squint at the amount of country between them and Pittsfield. It was a long way to go with the sun beginning to incline toward the horizon. He glanced up at the sky. A few stray cumulus clouds were heading westward at a perceptible rate. That meant they would have a brisk easterly cross wind most of the way northward. Winds mean something in an old and underpowered ship.

“But he’ll get there,” Jerry muttered, with grudging admiration. “Blast the old crab, he’ll get there! He always does.”

Beak Becket swung his ship abruptly into the wind and gave her the gun. Perversely he kept her tail down and her wheels on the ground until it seemed certain that she would crash through the fence. Jerry gripped the sides of the cockpit. But Beak, at the last second, bounced her off. He headed her upward in a zoom that continued until Jerry reached again for something to hang onto in the coming crash.

As the ship reached the stalling point, wavering in the air, Beak jerked her over onto her nose and regained control in a dive that brought the landing wheels within touching distance of the road. After this display he headed her prosaically on her course. The ship gained altitude steadily, her old ninety-horse motor thundering at full throttle.

“The crazy old crab, he’s a better airman than I'll ever be,” Jerry muttered. He turned around and discovered Beak grinning maliciously at the back of his head. Beak cut the gun promptly.

“Worried about your investment?” he shouted, in the sudden cessation of uproar. “If you’d been at the stick, kid, you’d ha’ been a bankrupt in hell right now!”

Jerry didn’t answer. While Beak was in control of the ship he was in a position to win any argument. And Jerry was in the forward cockpit—the one that hits the ground fastest and hardest.

He wriggled around in the small compartment until he had made himself fairly comfortable in the midst of the duffel. Then he looked over the map.

Pittsfield, as he figured it, was about two hundred miles away and the best that could be hoped for from this aged crate was sixty-five miles an hour—that would be an actual fifty, allowing for crabbing into the wind.

“We’ll be squeezing the gas tank and landing in the dusk,” Jerry prophesied. “I’m glad it’s Beak that does the flying. On paper it can’t be done.”

Beak coaxed the ship up to four thousand feet, to give the Jersey pine belt plenty of room under him. The wind was too strong, however, so he dropped down to fifteen hundred, where he straightened out. Slowly the dark green carpet, with the pines looking no taller than grass blades at that height, slipped behind them.

Jerry checked the course against compass and crosswind, and nodded to Beak. Then he settled down a bit farther in the cockpit, out of the wind and gloomily considered the chances of escaping from under Beak’s choleric thumb. It could be done only at the sacrifice of Jerry’s share of the ship, he decided, and he would never quit the ship he had paid for. He roused once from his meditations when the ship pitched suddenly. Turning, he discovered that the motion was due to Beak clamping the stick insecurely between his knees while he crouched low to light a cigarette.

Meeting Jerry’s inquiring eye, Beak gripped the stick angrily and shook it about. The plane reeled in the air and Jerry was rattled about among the baggage. He snapped on his safety belt and ignored the man behind.

“He’ll be making me shine those puttees and slapping my hand with a ruler,” he mumbled in deep discomfiture. “But he can’t shake me loose from this ship.”

Jerry sank back into the cockpit again and stared at the sky. Cross-country flying has its thrills, but it also has its monotony when indulged in too frequently.

Some time later, a hearty kicking at the back of his seat startled Jerry into realization of mundane affairs. He turned to his partner.

“Check ground speed!” Beak shouted, pointing downward. They were over a sizable sheet of water—Jerry recognized it from its contour and from the many ships as upper New York Bay. On the map, he reckoned the distance from the Battery to Yonkers ferry, about eighteen miles. He glued his eye to his wrist-watch while the ship, bumping erratically in the rough air above the skyscrapers and the Palisades, crawled up the Hudson. It took almost twenty minutes to reach the ferry slip.

“About fifty-four!” he shouted back, and Beak jerked his head in acknowledgment.

Jerry looked over the situation. The puffy clouds that had glided across their course above them had vanished. Instead there was overhead a thin, grayish stratum that moved inland, creeping in a sluggish race to overwhelm the sun before the latter could escape below the horizon. The air was smoother now, but perceptibly colder. They thundered on up the river. The eastern bank was still bathed in sunshine and its verdure was bright in color, but the high western cliffs seemed to brood beneath their mantle of shadow.

Just one hour later Jerry looked back at his partner somewhat distrustfully, and then turned his eyes very pointedly toward the sinking sun. He shook his head. The bridge at Poughkeepsie was not far behind them.

With a quick hand Beak cut the motor.

“You keep your damned hand still, you pink mouse!” he shouted vehemently. “I said Pittsfield and Pittsfield it is. D’you think I don’t know this country?”

He opened up again at once, preventing any back talk from Jerry.

The young aviator glanced down at the country on the eastern side of the river. Pools of whiteness were filling up the hollows in the ground. Mist, like a phantom ocean, was seeping up through the warm, porous earth into the cooler air. It was rising steadily—for so Jerry interpreted the growing size of the vapor-filled valleys. He scowled at it uneasily.

Another half hour passed and then Beak abruptly swung northeast, away from the river, across the misty earth.

“He’s trying to throw another scare into me,” Jerry decided with rising resentment. “He’s going to land at some field he knows this side of Pittsfield, after letting me think he’s flying right into the fog and the night. Well, I won’t scare.”

He clamped his jaw shut and stared with rising perturbation at the mixture of dusk and water vapor that was erasing the landscape. The ship itself still flew in brilliant sunlight, but somewhere down there in that growing gloom they must find a broad, flat space to set their landing wheels on. And broad, flat spaces below were scarce. The land high enough to escape the murk was the wooded tops of hills—the rolling, uneven Berkshires.

What fog can do to a ship is nothing compared to what fog can do to a plane. There is no stopping for a plane. It must keep on—on—on or fall.

Jerry looked down, behind the lower wing and then, as if following backward with his eyes some feature of the ground, turned farther and contrived to get a glimpse at his choleric partner without looking at him directly. He became aware, with a sudden jolt in his chest, that one of Beak’s hands trailed over the side of the ship and that the hand clutched a flat, pint-size flask. Even as he saw it, Beak raised the bottle and flung it sidewise, out beyond the tail. It whipped astern; vanished as if dissolved in the dirty grayness.

“Huh!” Jerry muttered. “Hope that stuff hasn’t made him too optimistic.”

He looked around for the sun, but it had vanished, like the bottle. He glanced at the compass. The ship was no longer flying northeast; it was headed due east. Even as he stared at the instrument, the ship banked abruptly, swinging around until it was flying southwest. Beak was retracing his course; he didn’t like things now, either.

Jerry turned then and examined the pilot critically and without dissimulation. Beak’s eyes seemed brightly fierce even behind his concealing goggles. His mouth was grim and tight-set. His big, curved nose was as rigid and motionless as if it had been turned to stone. However much, Beak had indulged in earlier that day, he was cold-sober now.

The ship roared on, flying a straight, unvarying course. Abruptly, Beak jerked a finger toward the obscured ground beneath; then pointed southwestward, toward the clearer air from which they had come. But there was no visible earth in that direction, either. The sun had been vanquished completely; black night and filmy whiteness had allied and spread over the earth.

The fact that Beak had condescended to make this gesture of explanation filled Jerry with alarm.

“If he messes up this ship, landing―” Jerry mumbled angrily.

The motor spluttered, thundered on a few beats more, and spluttered into silence. Jerry’s heart jumped. He remembered then that it had been some time since he had looked at his watch. The big tank in the upper wing had been drained dry by the hungry motor.

In a sudden frenzy of activity he flung his body half over the side of the cockpit and with cold fingers tore at the lashings of the five-gallon can of gasoline that rode on the lower plane. His heavy harness hampered his movements; the ’chute pack got in his way.

Beak put the ship into an easy glide.

“Don’t drop it!” he shouted hoarsely, as Jerry unloosed the cumbersome square can and raised it up. Standing on the edge of the cockpit with the wind whipping past him, Jerry got the cap off the gravity tank. He fitted in the short length of hose already attached to the gas can and let the precious fuel gurgle down into the tank.

Although the propeller was still turning idly in the windstream, the motor did not catch at once. That meant that Beak had switched it off; that, however much the bottle had contributed to this plight, it was no longer a factor.

Jerry screwed on the cap again and turned to the pilot.

“Thirty-five minutes?” he asked, with a nod of his head toward the replenished tank.

Beak was licking his lips.

“I can make it last forty,” he answered. His voice was strange to Jerry’s ears. Though he spoke against the wind, in a shout, the strength and confidence had gone out of it. The years of experience that had made Beak Becket so cocky a pilot now told him with relentless truth that they were in about the worst jam that could befall a flying man. Night coming; fog concealing the ground; gas failing.

Jerry wormed down into his cockpit again. He was green in this hard game, but he had the airman’s instinct, and he knew a hole when he saw one. Quite suddenly he became aware that he was in a parachute harness; that he was sitting on a ’chute—a life preserver that would carry him safely down through both darkness and whiteness to the good, solid earth.

He laughed, though his lips were so tense they were hard to command.

“He had a bottle; I’ve got a ’chute,” he muttered. “He used the bottle and got me into this. Why shouldn’t I use the ’chute and get out of it?” He did not touch the harness that girded him.

The motor picked up with a roar; then Beak throttled down. He was spiraling boldly earthward, spending his altitude recklessly as he sought to discover some loophole in the trap, some bit of ground still visible on which he could pancake the ship.

The air around them grew more thickly dark as they descended. Jerry felt like a man gone blind, groping his way with arms outstretched. Only dimly could he make out the loom of Beak’s head and shoulders just behind him. They corkscrewed on, but the spiral, Jerry sensed, grew less and less tight.

The feeling of something just ahead—something they were about to smash into—grew. Jerry gripped the cowling with rigid fingers. He had never been so cold before. He was cold to the heart.

Beak straightened out the ship.

There was no altimeter in Jerry's cockpit; he could not tell how high they were. He remembered, too, that the altimeter had been set for that flat meadow in Jersey—almost at sea level. There was no telling how much these blasted hills encroached on what the altimeter indicated was free air.

The motor roared into action again. Jerry’s body swayed toward the back of the seat. Beak was climbing again. He was climbing steeply, climbing as if some devil was pursuing him out of the black pit below. Jerry felt the terror, too.

The fate that Beak Becket had flirted with so casually that afternoon, merely to startle his partner, now appalled him. Death bulks larger in the dark.

Not until the luminous hand on Jerry’s watch had marked off eight minutes did Beak cease to climb and throttle down. For another interval, in comparative silence, the ship rode on the air.

They were in clean atmosphere; there were stars above them. Only the earth had vanished out of the universe. The interwing wires that Jerry had worked on that afternoon hummed a low threnody. The prop cut the air with a whistling, uneven flutter. They were cut off from the world—refugees in cold space.

“You better jump,” said Beak hoarsely. “The gas is going.”

Somehow the words revived Jerry’s courage. He did not answer, but he felt relief.

“I tell you, jump!” the pilot snarled. “Jump, I said! Jump, you―” His voice ran on in a tangle of oaths.

“I’m not going to jump,” said Jerry.

“You sap! You fool! You got a chance. Take it! Take it—quick!”

“I’m not jumping. D’you want the ’chute?”

“You trying to make a coward out of me?” Beak shrieked. “You can’t do it, you blasted little pup! Not me! I was in a ship when you was in a cradle! I’ll nose her down and dive her to hell before I’ll take a ’chute off you!”

His voice was keyed as high as the note of a flying wire under diving strain. Coming to him out of the darkness behind, it didn’t make Jerry feel any more secure.

“I’m sticking to the ship,” Jerry said stubbornly. “It’s half mine, and I’m sticking.”

Beak burst into high, jeering laughter. “You fool! Don’t you know there won’t be enough left after we hit to make you a coffin?”

“We’ve got a chance. Beak! Listen, Beak!” Jerry’s voice became vibrant with urgency. “You want to gamble on this? I’ll give you the ’chute and three hundred—about all I’ve got—for the ship—just as she flies, Beak.”

The man in the rear cockpit was mute. Jerry, turning to squint at his head and shoulders in the blackness, could see no sign or motion. But the ship, responding to Beak’s hand on the stick, shuddered in the air.

“What d’you say, Beak? It’s a gambling proposition. I’m sticking anyhow—so the ’chute’s no good to me. I’ve got a hunch, Beak, and I want to play it. Three hundred—right here in my pants pocket—three hundred and the ’chute.”

“Go to hell!”

“I’m willing, Beak. I want to back my hunch.”

The ship sang on in the still air.

“You’re a crazy damn fool!” Beak growled.

Jerry did not answer him. It was up to the pilot now.

“Crazy! Dumb! Gi’ me the ’chute! Get set to take control! Crazy! Hurry up!”

Hastily Jerry worked at the buckles. He felt only like a man easing himself of a burden. Finally he wormed out of the harness. He passed it and the ’chute pack carefully back to Beak. Then, steadying the ship with his own stick, he waited silently, sensing every move of the struggle Beak made in getting into the straps.

“Here’s the money, too, Beak,” he called, leaning down the fuselage and groping for the other man’s hand. He could not locate it.

“This is your own damn foolishness—I didn’t have nothing to do with it,” Beak said thickly. “I warned you!”

“That’s right, Beak. But I want to back a hunch. If it don’t go through—you can’t be blamed any, Beak.”

Suddenly Beak’s rough fingers met Jerry’s. The roll of bills was jerked out of his fingers.

“Ready to take her over?”

“Wait a minute!” Hastily Jerry groped in the cockpit to make sure that none of the duffel was apt to jam the controls. “All right, Beak!”

“Take her! How about some altitude? This ’chute’s got to have plenty room to open.”

“Right!” Jerry’s hand was controlling the ship now, and his feet were on the rudder bar. Danger was lost in exultation. The ship was his. His to fly—his to own. For a while, anyhow. He notched up the throttle.

The motor picked up. With gentle pressure he eased the stick toward him. The ship straightened out and began to climb. He had held her on her upward course for fifteen minutes when Beak kicked his seat.

“All right,” he said, when Jerry throttled down. “Let her glide. D’you see anything?”

His hoarse voice had an appealing note. But there was unbroken gloom beneath them. Jerry had been looking, too.

“Nothing nearer than the stars,” he answered.

Beak climbed onto the fuselage, holding onto the cowling with one hand, while his feet dangled over the side. His other hand, Jerry knew, was on the rip cord of the ’chute.

“Ten years ago I’d ha’ told you to go to hell!” he said bitterly, and shoved off.

His body was visible as a sprawling thing for an instant, then vanished absolutely. Jerry, staring backward, caught a dim flare of near-by whiteness—the opening parachute.

“Poor Beak!” he muttered, with a searing pity of youth for age.

He turned forward again. The stick rattled and the plane moved uncertainly. Jerry tightened his fingers and the ship ceased its erratic motion.

“I feel as if the tail had dropped off her,” he muttered.

The sense of emptiness behind him in the other cockpit made his back feel uncomfortable. He switched on the motor. Its roar made him feel better.

“No use sticking around up here till she quits,” he decided. He picked out a star and flew toward it for several minutes, to give Beak plenty of room in descending.

With a piece of his shoelace he suspended his jackknife, pendulum-fashion, from the unlighted instrument board in front of him. Then, gingerly, he set the ship up on one wing in a tight spiral, as Beak had done. The man and plane spun downward toward the hidden, unfriendly earth.

He waited, occasionally staring downward, occasionally looking upward, to see if the stars were still visible. They were. He whistled, as well as he could. He had a long way to go yet. Then suddenly, wisps of vapor, like an army of specters, assailed the ship. He was in it.

Hastily, even frantically, he straightened out and put her into another glide. He found that drops of water were rolling down into his eyes from under his helmet. The windstream made them cold. He pulled off his goggles. With or without them he could see nothing.

“If I can just keep her in a glide!” he muttered. He put out a hand and found the jackknife. Though it was swinging gently, its position indicated that the ship was in normal flight—or making a normal banked turn.

He kept his head well up above the windshield, alert for any vagrant breeze on either cheek that would tell him the ship was not flying straight ahead. By the feel of the wind and the sound of the wires he kept the ship in a glide —as slow a glide as he dared. He checked every impulse to move the stick. When he did move it, he did so very slightly, much less than he felt was necessary. He kept one hand near the jackknife.

Through the dark whiteness the murmuring ship glided on. There was nothing to see, but Jerry’s vigilance grew more and more painfully intense. His eyes ached. His chest felt hollow.

“Damn it! How long is this going to last?”

He groped for his flash light and trained it on the fog ahead. The mist became a white, opaque wall, more impenetrable than the darkness had been. He switched the light off, tucked it in his pocket and put his hand out to the jackknife again. It was not where he expected it to be, but to the right. He edged the stick over to the left.

The landing wheels under him suddenly struck something; the ship jarred harshly. In another instant the nose went down. Jerry was slung violently against the instrument board. His safety belt cut into his body. He cut the motor. Something was happening to the ship. Noises were all about him—rasping, squeaking, swishing, creaking sounds.

He struggled upward again and dimly felt that the ship was bounding along, seemingly with increasing speed. Yet the motor was cut, the propeller was idle. It was like a delirium, a nightmare in the dark.

Abruptly he realized that the ship was on a hill or a mountain, rolling downward precipitously despite the drag of the tail skid. There was nothing he could do. He braced himself and waited.

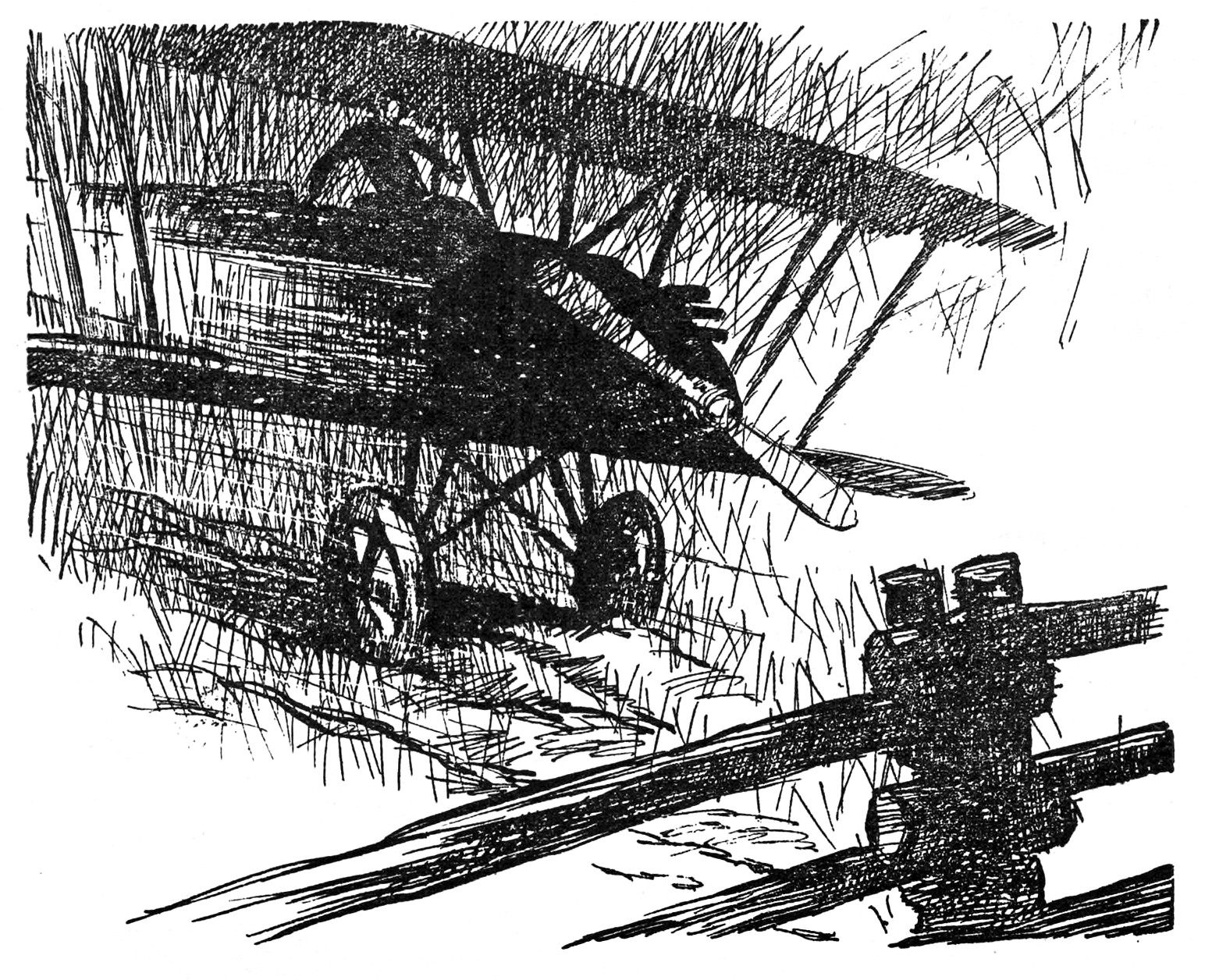

He did not wait long. She struck something too high for the wheels to rise over. There was a crash. Jerry felt the cockpit rising under him—up and up—and then down. Some object in the darkness thrust at him, and his consciousness left his body with his hissing breath.

There was a blurred interval. Then he found himself struggling feebly against some powerful force that held him unflinchingly about the waist. His fingers came in contact with a familiar thing. It was the catch of his safety belt. He jerked it and instantly the force that held him ceased to exist. He fell heavily on his head and knees. It was grass that he dropped onto.

For a time he lay there, less than half conscious, but quite incapable of movement. There seemed no reason to move, even if he could. Then, gradually, he made up his mind to shift his body off something that was boring cruelly into his hip. Groaning, he did so. He felt the thing and found that it was the flash light in his pocket.

Pulling it out, he raised himself to his hands and knees, and rested there. Through his head was running a flood of thought. He had tried to land in the darkness. He was on earth now, and not dead. The thing to do was to see how badly he was hurt and the ship― What of the ship—his ship?

He raised himself up off his hands. He felt the smooth fuselage of the plane above him and then a wire. With what support he could gain from the wire, he got to his feet. He turned the flash light on the plane and pressed the button.

The white radiance, clouded by the mist, traced out the lines of the ship. She was on her back. But she was not the mass of crumpled wreckage he had feared to see. The thing she had hit was a heavy rail fence. Instead of going through she had rolled over it.

“Cracked up—but not washed out,” he muttered. “If that motor―”

He dragged himself toward the nose of the ship. The prop was a splintered stump. But the motor looked good—pretty good. It takes more than a nose-over to ruin a chunk of metal.

He felt his ribs gingerly.

“I've got something gone in there,” he reckoned. “But I guess I’m a pilot now—and in about a month I’ll have a ship—my own ship. That hunch worked fine. I'm a pilot now.”

He looked at the plane and his mind was busy with the thought of a box splice for a broken spar of the lower right wing.

“Poor Beak!” he muttered. “He should ha’ stuck.”

Transcriber’s Note: This story appeared in the August 7, 1929 issue of The Popular Magazine.