Here is a murder detective story of a different type, which we warmly recommend to you. It again shows that circumstantial evidence may not always be 100 per cent right, and that one should not always jump to conclusions. The science part of this story is extremely ingenious and can be duplicated at any time for use in similar cases.

When Dr. Milton Jarvis descended the plank of the liner Homeric, on his return from the International Medical Congress at Vienna, in the year 1926, he expected to find his most intimate friend, Jim Craighead, at the pier to meet him. He looked about him, somewhat disappointed, then disconsolately walked over to Broadway, where he stopped to buy a paper before hailing a taxi.

For more than two weeks he had not seen a paper. He was busy with the notes he had made at the Congress, which he was pledged to read shortly after his return, to the American Medical Association. Hence, it was with more than ordinary interest that he looked at the glaring headlines of the New York journals, so much more blatant than those employed by the European press.

One glance at the first page of the newspaper informed him why Jim Craighead had not met him. He shut his eyes for a moment to assure himself that he was not dreaming—that he really was home and not with the medical celebrities who had gathered at Vienna. Dismay, horror and unbelief strove alternately for mastery. It was impossible—Heaven would not permit such a crime. “Craighead inquest perfunctory” read the streamer. “Well-known banker dies of shock following operation.” Craighead, it appeared, had slipped while dashing for a train. The platform was wet—the train was already in motion—he missed his footing, one leg going under the wheels. Amputation became necessary, fatal blood poisoning having set in.

The inquest had begun that very day. Very little testimony had been taken when the edition Dr. Jarvis was reading went to press. It was after two o’clock in the afternoon when he got into the taxi, and the doctor immediately resolved to hear what he might of the remainder of the testimony.

Leaning out the window of the taxi, he called: “Drive me to the Coroner’s Court, please.”

In a few minutes he stood in the court room just before the Coroner adjourned the Court for the day. The attending physician was on the witness stand completing his recital of the patient’s treatment.

“Now, Dr. Lawson,” asked Mr. Bailey, a lawyer representing an insurance company in which Craighead held a large policy, “how did you treat your patient? I understand that amputation was necessary as soon as Mr. Craighead reached the hospital.”

“That is correct,” replied the doctor.

“Were all the usual precautions taken?”

“Oh, yes,” said Doctor Lawson, “I attended to that myself. The wound was perfectly sterilized. Then I attached the haemostats.”

“What do you mean by that?” asked Mr. Bailey.

“Little clips are used to fasten the ends of the severed blood vessels. Afterward, they are replaced by gut which is tied around the blood vessel, gradually being absorbed as healing progresses,” replied the doctor.

“And with all these precautions, the shock of the operation killed Mr. Craighead?”

“That is true,” assented Dr. Lawson.

“That will be all for today,” said Mr. Bailey. “Tomorrow, I will want to ask you a few questions.”

The lawyers folded up their papers preparatory to leaving the court room, while the large crowd which had gathered out of curiosity to hear how one of the wealthiest bankers of the city had met his destiny, slowly filed out. Dr. Jarvis, seeing the physician of the insurance company, whom he knew well, at the table, joined him as he packed a sheaf of papers into a wallet.

“What do you make of it, Fulton?” he questioned the doctor.

“So far, we have learned nothing, Jarvis,” said Dr. Fulton, slowly. “I know how close you and Craighead were. You must feel terribly shocked. It seems clear that the operation killed him. There is no ground for suspicion, but we must make some kind of fight, before we pay a $300,000 policy which has been in force only six months. He left a large estate too, as you probably know.”

Dr. Jarvis went home in a deep, brown study. He was shocked and horrified by the loss of his dearest friend. He could not reconcile the thought that this big, hearty person was the victim of blood poison or shock. Why, the man had always been immune. He had been proverbially tough, bubbling over with vitality. “How had he lost that immunity?” he asked himself. He recalled their last day together—the day before he had sailed for Europe. They were playing tennis at the country club.

Dr. Jarvis, trying desperately to prevent his rival from scoring the last point in a hard-fought game, swung down viciously on a high bounding ball, sending it back low over the net in what looked like a volley, impossible to handle. But Jim Craighead whipped his racquet up in a swift lawford and the ball, like a shot from a gun, sped down the side line far from the doctor’s reach.

“Damn,” he cried, “trimmed 8 to 6 by a man of fifty and I’m your junior by ten years. But you sure do keep in condition.”

“Doc,” answered Craighead, “just three months ago, when I took out life insurance policies for $300,000, the examiner said he would like to have a dozen risks in my condition. I can run a mile at a good pace and do any stunts in the gym that a kid can do.”

“That’s right, Doctor Jarvis,” chimed in a young man of twenty-two, who, with a beautiful girl about the same age, had just run up to the clubhouse in Craighead’s sedan, “he made me go some to keep ahead of him in a long swim, though he didn’t even know the crawl.”

Doctor Jarvis recalled that picture now—the great, tawny-haired Craighead towering above his adopted son’s head, his arm fondly on his shoulder and the youth’s arm about the girl’s waist. The girl, the jewel in the setting, had light hair, neither golden nor yellow, although with a touch of autumn wheat; she was delicately featured, with an expressive mouth, inclined to be serious. Now, with these two men, apparently happy and smiling, she revealed very regular, white teeth. Ross Craighead was almost as tall as his adopted father but slender; Jim was wide shouldered and robust. The girl, although tall, seemed diminutive beside these two.

If the beautiful girl and the handsome youth seemed well and full of vitality, Jim Craighead was almost insolent in his defiant heartiness. Ross was the orphaned son of Craighead’s sister who had died when he was a few years old. The bond between these two was very strong—Ross was a sensitive soul, of the artistic type, against which characteristic the buoyant Craighead had waged a losing fight. The boy could not be hardened.

At college he was all for humanities, classics, science, logic, but close calculation in business seemed to have been left out of his nature. Sports had attracted him—he was good material for the teams, especially in baseball and swimming. Just as Craighead had determined that he would be hopeless in the banking and brokerage operations which he controlled, Ross had met Tessie Prettyman, who was secretary to Craighead’s manager. Her efficiency was due to the fact that she took every instruction seriously and obeyed implicitly. She believed anything she was told, which was inconvenient when she was listening to a rival of the firm.

Craighead was inclined to discourage the intimacy he saw growing between the pair but when Ross began to grind earnestly at tasks Jim knew the boy loathed, he began to consider the girl less a liability than an asset. She was an orphan, that was all they knew of her history. But she was well educated, a lady in all her actions, so that Jim soon grew as fond of her as Ross. This, then, was the circle which had been broken up by a tragedy so unnecessary in Dr. Jarvis’s mind as to be heartbreaking.

Like all healthy men—men who have never felt an ache or a pain, Jim was virtually a baby when some slight cut or other wound came in a tennis or other game. Once Doctor Jarvis had found him taking morphine. Jim had said, rather shamefacedly:

“It’s not a habit, Milt, but I just can’t stand pain. I’ve never had much, I guess that’s the reason.”

This last day he had seen Craighead, the recollection of which came to the doctor’s mind over and over again, the young man had taken the front seat with Tessie, while Jim and Doctor Jarvis sat in the rear.

“Jim, old man, I’ll be missing you,” said the doctor, as they left him at his apartment.

“We’ll be waiting at the pier when you come back, Milt, twice as famous as you are now,” was Jim’s reply.

That was like him. He had helped Doctor Jarvis through his early difficulties and setbacks, encouraging him and rejoicing in his successes. He was foster father and pal in one. So Doctor Jarvis was very impatient as his brain refused to accept the fact that Jim Craighead was dead.

In no way could he reconcile his sturdy friend’s death with a theory that the shock of an operation would kill him. His analysis was searching. Nothing in his experience was overlooked. He was skilled in X-ray therapy as well as X-ray photography. His science was modern—the latest researches were commonplaces to him. But facts were what he needed, after all. No conclusions could be drawn from surmises. This thought drove him to the room of Inspector Craven at headquarters. They were good friends, for the doctor had often given expert testimony in trials in which the inspector was interested.

“Inspector,” began Dr. Jarvis, “what do you know of this Craighead inquest?”

“Well, Doc,” replied the inspector, settling his huge frame back in a capacious chair, as he wrinkled his thick brows and blew the smoke from a vile smelling pipe through his walrus moustache, “inquests are not much in our line unless there is some crime involved. This is such a clear case of a man dying from the shock of an operation that the police have no more interest in it than the public. Of course Craighead was a big man. I knew him well myself. He used to stop here to pick me up sometimes, so I got to know what an impatient chap he was. He told me that he’d sprint for a car, whenever he had to ride on a street car, like any kid of seventeen. The insurance company would grab at anything suspicious but nothing has come up. We all know the story. Craighead got too cocky in his sprinting ability, and was run over. It was mucky and rainy, so what followed was almost inevitable. Tough on the insurance companies, though. Doc Lawson seems positive that it was the shock of the operation.”

“That is just why I don’t feel satisfied,” said Dr. Jarvis. “Lawson is an old practitioner, a good surgeon, but very apt to make up his mind what killed his patient. The more you might show him the probability of some other cause, the more stubbornly he would believe in his own theory.”

“There are quite a few of us like that, Doc,” smiled the inspector. “But, you knew the whole family. Is there anyone who could profit by Craighead’s death?”

“Well, there is Ross, Jim’s adopted son and his nephew. But he had all the money he needed—he was in the business with Jim. Then, too, Jim made no secret of the fact that his fortune was to go to Ross. So I think that Ross is out of the question, for they were devoted to each other. Ross is the idealistic type—he would be more apt to give money away than try to get it by murder.”

“Who else is there?” queried the inspector, indifferently, for he could see no mystery in Craighead’s death.

“Then,” continued the doctor, “there is the girl to whom Ross is engaged, a perfectly innocent creature who simply adored Jim—he treated her as if she were already his daughter-in-law. She is an orphan, Tessie Prettyman.”

“Tessie Prettyman!” exploded Inspector Craven, “Good Lord, Doctor Jarvis, do you know who Tessie Prettyman is?”

“No, she has no family that we know of, but she seems to be a very refined and charming little lady.”

“Well,” said the inspector, bouncing from his chair, “Tessie Prettyman is a girl who has been visiting Piggy Bill Hovey down in the Tombs. Piggy Bill is held on a narcotic charge, without bail, because he was caught with a large supply of morphine, opium and heroin; the Federal boys want to find out where he gets that stuff because he can’t be connected with any smuggling operations. Our men have watched the girl and she seems to know Piggy Bill very well. Some of them think she is his sweetie. But if Piggy Bill is anywhere on the horizon, I am willing to be suspicious about Craighead’s death.”

This revelation grated on Dr. Jarvis. He did not believe for a moment that this sweet-looking girl had any criminal tendencies or was capable of playing such a dual rôle as the affianced of Ross Craighead and the “sweetie” of a notorious criminal.

“Inspector,” he said finally, “have you time to go up to the hospital with me? The records or the head nurse might tell us something.”

“Time, time,” roared Craven, “this is official business now. What we have to learn is how Piggy Bill’s sweetie happens to be engaged to marry Jim Craighead’s son. First thing, we’ll go to the hospital, then we’ll talk with this young man who seems to be infatuated with Tessie.”

In the inspector’s big car it was a short trip to the hospital. The records told them nothing new. It was Dr. Lawson’s case, so that whatever he might have to say would be developed at the inquest. But for the fact, suddenly unveiled, that Piggy Bill was somewhere in this series of events, the inspector would have remained seated in his big chair, serenely puffing on his pipe.

“Doc,” said the inspector, suddenly, “let’s talk to the head nurse first, then we can look up the young man and Tessie.”

“Miss Cornhill,” asked the Doctor, when the head nurse appeared, “did you see Mr. Craighead when he was brought into the hospital a few days ago?”

“Of course,” replied the nurse.

“How did Mr. Craighead seem to you?” he queried further.

“Doctor Jarvis,” the nurse said, “Mr. Craighead was very badly hurt. He was not a patient sufferer—he stood the pain irritably and was relieved when it became necessary to etherize him. He asked the doctor to give him a hypodermic a couple of times, but the doctor refused.”

“That was like Jim,” murmured Doctor Jarvis.

“But,” continued the nurse, “he should not have died from the operation under normal conditions. Of course his mental condition was very bad. He was a very handsome man, in fine physical condition and he moaned, time after time, “I had as lief been killed as lose my foot.”

“When Mr. Craighead was taken home, Miss Cornhill,” asked the doctor, “did one of your nurses accompany him?”

“No, sir,” was the reply, “Mr. Craighead insisted that his son and the young man’s lady friend be with him—anyone else, he was sure, would irritate him more than help.”

“Thank you, very kindly, Miss Cornhill,” said the Doctor, and they left the hospital.

“Well, inspector,” began Doctor Jarvis, when they were seated in the car, “we didn’t get very far at the hospital. If it lies between Ross and Tessie, I guess it may as well end where it is.”

“See here, Doc,” said the inspector, gripping Doctor Jarvis by the arm, “you’ve started me looking for a murder or some crime and by the eternal, you are not going to let any sentimentality about a pretty girl check our investigation until we know that there is or is not a crime.”

“Inspector,” replied the Doctor, with a hard glint in his eye, “as long as there is any doubt as to how Jim died, I am with you to the end. I simply meant to express my opinion that neither of those two could be involved. Let us look the situation in the face. Dr. Lawson has certified that Jim Craighead died of natural causes. That prevents any kind of action until the inquest reveals something of a suspicious nature. In fact, there would have been no inquest but for the insistence of the insurance company. Now, we must develop something that points to some unnatural factor in Jim’s death before the inquest is over.”

“That’s true enough,” replied Craven, “and we don’t want to alarm anyone until we have the goods on him. You be at the inquest bright and early and keep your eyes and ears wide open. I will find out when Tessie went to see Piggy Bill last and join you later.”

The inspector left Doctor Jarvis at his door, a prey to many conflicting emotions. He had started machinery going which he knew could no longer be stopped. But he did not want to leave Ross open to an insidious attack. His efforts to communicate with him, however, were unavailing. After a sleepless night the doctor refreshed himself with a plunge, a shave, and then having dressed himself in a sombre garb which fitted well with his present emotions, went to the Coroner’s court. It had just opened with Dr. Lawson on the stand.

“Now Doctor,” began Mr. Bailey, representing the insurance company, “you were describing, yesterday, the nature of Mr. Craighead’s injuries. You mentioned fastening the haemostats yourself. Will you tell the coroner and the jury what you mean by that?”

“Why, yes,” answered Dr. Lawson, “to use layman language, haemostats are little clips which are applied to the ends of all the severed blood vessels when we amputate, thus closing them so tightly that no foreign or toxic substances can find their way in.”

Dr. Jarvis leaned over to the physician of the insurance company whispering, “Fulton, why doesn’t your lawyer ask him how the shock of the operation or blood poison could kill him, if the haemostats were properly applied?”

Dr. Fulton communicated this message to the lawyer who immediately shot this question at Dr. Lawson.

“Dr. Lawson, if the haemostats were properly applied, how do you suppose the poisonous substances got into the wound, if the wound was sterile, as we must assume it to have been after the operation at the hospital?”

“Well, one way, which I assume to have been the true way, is that the poisons made their way through the wall cells of the blood vessels—the arteries, veins and capillaries,” replied Dr. Lawson.

At this reply, Dr. Jarvis shut his lips very grimly. He was making progress at last. Very opportunely, at this moment, Inspector Craven slipped into the chair next to him.

“Doc,” he murmured, in a low tone, “we are on the track of something—Tessie visited Piggy Bill twice, the day before Craighead died. He’s a bad egg, but we never have caught him in anything red handed except this narcotic deal. He’s bad, though, bad enough for anything. Now, here’s another funny thing about Piggy. He’s an educated rogue, talks French and is a great student of toxicology. How does that fit in with your story now?”

“Inspector,” said the doctor, “I don’t know yet where we are heading, but that last remark of Doctor Lawson’s shows me that Jim did not die of the causes ascribed. Now we must find out what did cause his death. With a few more facts, I think I can clear this mystery. I’m half tempted to take a hand right now.”

“Wait until you have the whole story,” advised the inspector. “If we have to make any arrests, we don’t want to warn them in advance.”

“Doctor Lawson has just made a bad break,” said Dr. Jarvis, “which makes it easy to show him up, although I hate to discredit him. He really is a good surgeon, but he’s not modern enough. We must get all the information we can from him before he suspects we are after anything.”

He then scribbled on a piece of paper, “Ask who nursed Craighead.”

In a few seconds the lawyer asked:

“Dr. Lawson, Mr. Craighead was in charge of a nurse, of course?”

“He was in good hands, Mr. Bailey,” said Dr. Lawson; “it was his own wish that his son Ross and Miss Tessie Prettyman, of whom he seemed to be very fond, should be with him and administer his medicine.”

“Is Miss Prettyman here?” queried the lawyer.

“She is sitting just back of you.”

“That will be all for the present, thank you, doctor,” concluded Mr. Bailey.

“Miss Prettyman, will you take the stand?” asked the coroner.

Both Dr. Jarvis and the inspector looked keenly at the girlish figure which mounted to the witness box. She was tall, well formed, with a wealth of blond hair which surrounded a very beautiful, expressive face, now drawn with worry and late vigils.

“You nursed Mr. Craighead during his last illness, did you not, Miss Prettyman?” asked the lawyer, after the usual preliminaries were over.

“Ross and I took turns, and sometimes both of us sat with him together,” said the girl. “He grew fretful when one or the other of us was away for even a minute.”

“Did you give him his medicines?” continued the lawyer.

“Sometimes I did and sometimes it was Ross,” said the girl in a low voice, in which a slight catch of emotion was discernible.

“Gad, Doc,” snapped the inspector, “where is this young chap? If he knows anything we can sweat both him and Tessie.”

“There he is, three seats over,” replied Dr. Jarvis. “One look at him ought to satisfy you.”

They looked at the tall, well dressed youth—about twenty-two he was—a sincere, dreamy looking chap, yet now with his lips tightly compressed, evidently resentful of the way the girl he loved was being prodded.

“Miss Prettyman,” queried the lawyer, who as yet had not caught the drift of Dr. Jarvis’s prompting, “how did Mr. Craighead die? Describe his symptoms.”

“I can hardly tell you that,” answered the girl without hesitation. “Ross would lie down for awhile in the adjoining room, with the door open, whenever Mr. Craighead dozed off late at night. Mr. Craighead died very suddenly, for I ran in a very few seconds after Ross had cried that he was in danger. Ross, of course, saw him die but would tell me nothing about it. He said it was too awful.”

“Now is the time, Doc,” said the inspector, all his detective instincts aroused. “We’ll see what the boy says and then, if it throws suspicion on him, we can see how deep is the affection of Piggy Bill’s sweetie.”

In the girl, the inspector, looking for important revelations, saw now, not a pretty girl, but the possible accomplice of Piggy Bill Hovey in some foul deed.

“Swear Ross Craighead,” said the coroner, who did not know whether he was to be bored with a lot of insurance statistics or was to face a drama not yet unfolded.

The buzz of conversation in the courtroom ceased as Ross took the stand. No one knew in what direction the inquest was tending. Even to the coroner this long rehearsal of symptoms without any avowed purpose seemed unnecessarily delayed. Inspector Craven’s presence puzzled him. He did not especially relish having the police oversee his conduct of an inquest. He asked rather curtly that the proceedings be hastened.

“Mr. Craighead,” began the lawyer, “were you with your father in his last hours?”

“I was,” answered Ross, sadly.

“Did you purchase the medicines administered to him?”

“No, sir,” was the reply. “He was very querulous if I left his side. When I dozed off, he often called me just to talk. He felt the loss of his activity so much it was pitiful. Miss Prettyman, who loved him almost as much as I did, for we were always together, never minded going out for whatever he wanted, day or night.”

“I should say not,” muttered the inspector grimly to Doctor Jarvis.

“Now,” pursued the lawyer, obedient to the doctor’s prompting, “how did your father die? I do not want to deepen your pain, but we must get at some understanding of the exact cause of your father’s death.”

“Well,” answered Ross, wearily, “he insisted on taking opiates; he knew how to take a hypodermic himself, but he took some other drug, heroin, perhaps. He was not a drug addict, but he often said that he would take anything to drown pain. It happened like a flash. I did not know that blood poison could travel so fast. The night he died he took an opiate and seemed drowsy, so that I said I would lie down for a moment or two. He took a bottle in which was a colorless liquid and poured some of it into a glass of milk. He was half asleep then, so I went to my room while he was drinking it, for he often took a glass of milk in that fashion. I had had very little sleep for two or three days and dozed off at once with all my clothing on. I could not have slept more than a quarter of an hour when I was awakened by a crash. It was the crash of breaking glass, as I learned an instant later. I rushed into his room to see him breathing his last. He had overturned the table on which were the bottles of medicine. But what a terrible sight greeted my eyes! His hands, arms, legs twitched and shot out from second to second, then before I could even call for help he had a convulsion and died. I called Dr. Lawson. It seemed an eternity before he answered. Miss Prettyman had heard my cries and she was with me. Dr. Lawson asked if he had taken anything besides the medicine he had prescribed. I said yes, he had taken a hypodermic and some other opiate.

“The hopeless fool,” he cried. “I warned him against that very thing. He practically killed himself. The shock of the operation was enough at one time.”

When he reached the house, he said it was too late to do anything.

“Did you look at the bottles on the floor?” asked the lawyer.

“Yes, sir,” replied Ross. “They were all thrown together in a broken heap—they had been on a small table at his bedside. In his struggles, he must have overturned them. Oh, it was terrible, terrible.” Here, the young man buried his head in his arms, shaking with the power of his emotions.

“Inspector,” said Dr. Jarvis, “that young man was describing a death from strychnine poisoning. We must find out where that strychnine came from. Look at that girl now!”

The inspector followed his gaze to where Tessie sat. She was obviously horror stricken. A look of despair crept into her face as she followed Ross’s descent from the stand. Ross was about to go to her side but at a sign from the inspector an officer took him by the arm, leading him to a chair near the inspector. His heart sank as he caught that look of despair on the girl’s face.

Every actor in the drama was apparently in court. Dr. Jarvis had caught the inspector’s fever for a man hunt. It was now a cold problem of science. He was not a judge, merely an instrument of justice. No longer was there a thought in his mind, any more than in that of the inspector, that any person should be shielded. He was going, from now on, to let the chips fall where they would.

“Inspector,” he said, “the whole situation now depends on how much that girl knows. I am going to ask Mr. Bailey to put me on the stand. I see exactly how the affair was managed, but I haven’t the slightest idea of who planned or executed it. Anyway, when I get through, if Ross or Tessie had any hand in it, they will talk better than if they were subjected to the third degree. I am talking of murder now; when I am through, it will be your affair to bring the guilty person to justice.”

“H’m,” mused the inspector a second, as if in doubt, then posted his men with orders to let no one leave the court room until he gave the signal. “There might be others,” he reflected, “so why not bag them all?”

Dr. Jarvis now stepped to the table where counsel and doctors sat. After a few whispered words, Mr. Bailey rose to his feet.

“Mr. Coroner,” he said, “one of our most prominent physicians, an acknowledged authority and the closest friend of the deceased, is our next witness. His testimony may clear up some of our difficulties.”

The pursued rarely are ignorant that they are pursued. As the lawyer concluded his announcement, Tessie half rose to her feet, but an officer forced her back into her chair. She realized then, that she was in custody. She had indeed, divined before that the inquest had taken a threatening turn. Ross dully watched the progress of events thinking how he might shield her from persecution. Lovers are impersonal. The world is outside. To him, Jim Craighead was still alive. Suspicion did not enter his mind. It did not occur to him that he might be suspected of murder. Still less did he conceive that anyone would accuse of complicity in a murder, the girl, who to him, was the impersonation of innocence. That a net of some evil omen was weaving about them was too evident to be ignored. Its nature, however, was a mystery to him. Yet when the doctor, a man whom he knew for the devoted friend of his foster father and, as he thought, also of himself, got on the stand and began to speak in that sure, even voice, which seemed to brook no contradiction, he looked somewhat hopefully at that dynamic figure. The doctor was a tall, slender man, athletic and erect in appearance, with a firm, intellectual face.

Dr. Jarvis was sworn. He was then examined on his various degrees, his experience, his scientific and other studies. Mr. Bailey, instead of asking a series of questions, requested him to give any testimony that might throw light on the death of Jim Craighead.

“I would like you to bear patiently with what I have to say,” began Dr. Jarvis, “interrupting, if you like, when I have not been sufficiently clear, for whatever questions you may care to put.

“Singularly enough, the mysterious death of the best friend I have ever known ceases to be a mystery through a remarkable scientific discovery which I must rehearse briefly. It is the relative size of the smallest bodies known to science. The structure of the atom has been analyzed. The atom is the smallest particle of matter which can exist independently. The elements which enter into the atom have no existence apart from the atom. The atom is the smallest particle of matter which can enter into the structure of the molecule. But it is not indestructible. It has been broken up into its elements. These consist of outer circulatory electrons which are negative charges of electricity and a core or nucleus composed of positively charged protons and some electrons, all in balance. These electrons are in constant motion within the atom, revolving about the nucleus much as the planets revolve about the sun.

“Now, this discovery led to the measurements of these tiny particles. Science wanted to learn more about the relative masses of atoms and molecules. The electron is about one thousandth the volume of the hydrogen atom. Do not think this is all a pedantic discussion. You will see in a very few moments how very practical it all is.

“The atom,” continued Dr. Jarvis, “is invisible under the most powerful microscope. The molecule is larger, but defies the microscope. But, having gone thus far, science had to go further. The next larger mass after the molecule, is the colloid. A colloid is a formless substance classified as a slime. It never takes a definite form like the crystalline substances. Solutions of gold can be made in the two forms—there is a colloidal gold and a crystalline gold.”

A look of stupefaction was on the faces of the inspector, the coroner and all that vast throng in the courtroom. Yet a pin could have been heard, had it dropped during that tense silence. Back of these mystic words an enigma lay. That the doctor would clear it up, his easy self assurance seemed to guarantee.

“Even the colloid practically battles the microscope. In the ordinary atmosphere, merely cloudy impressions can be obtained. How then is the presence of any of these tiny particles discovered? It is very simple, when the method is disclosed. The colloid cannot be seen, but it makes a shadow on an electric spark as it passes by. So when the presence of a colloid is suspected, its shadow on an electric spark betrays it.”

“Pardon me, Doctor, for interrupting you,” broke in the bewildered Mr. Bailey, “but if this discussion has any bearing on the death of Jim Craighead, I would like to know, if these particles you are talking about, are so small that they cannot be seen with the strongest microscope, how it helps you any to know they make a shadow on an electric spark. In fact, how do you know they make a shadow on an electric spark?”

“You may have read at times, Mr. Bailey,” replied the doctor, “announcements that astronomers had located a star known through mathematical calculations to be at some point in the heavens, which the telescope has been unable to penetrate. Well, the speed of light, which is 186,000 miles a second, helps us. A photograph of the heavens will sometimes reveal something which the eye could not see. So, a photographic plate will sometimes catch the smaller particles as well as the largest stars, too far away to be seen.

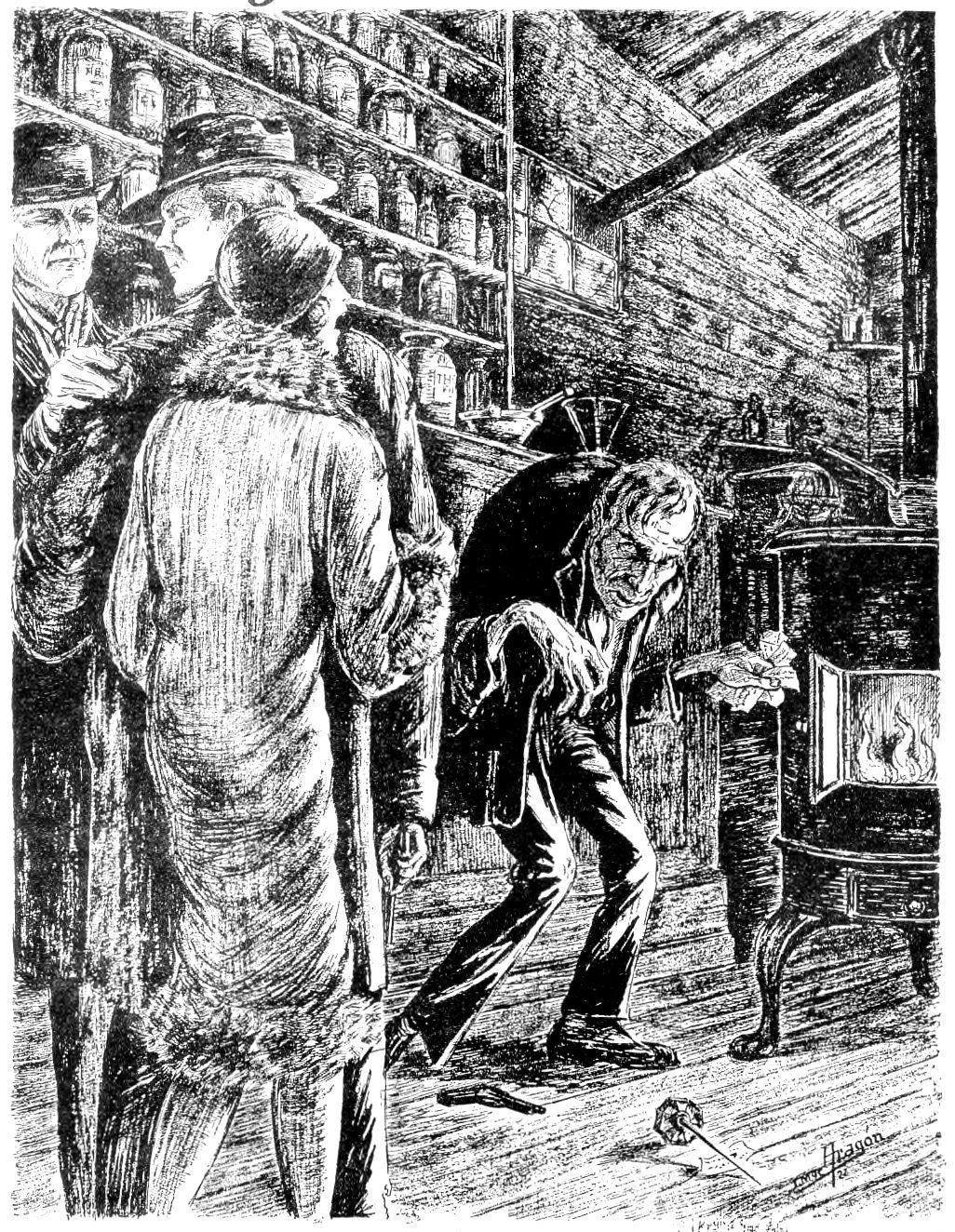

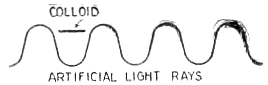

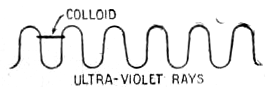

“If you consider the light as moving in waves it is easier to understand what effect light waves have on these discoveries. Artificial light travels in waves farther apart than in the case of natural light. The waves of this kind of light are so far apart that the colloid or small microbe can lie between the waves and make no impression on the eye or on the photographic plate.” The doctor here took a sheet of paper and hastily made a sketch which he showed to the jurors and the coroner.

Artificial light waves:

“The waves of natural light are closer together, but still too far apart to catch much of the smallest germs, like that of cancer, or the colloid, to advantage.” The doctor made another sketch.

Natural light waves:

“In natural light, under the microscope, it is at times possible to get a hazy impression which conveys little information. But it has been found possible to use the ultra-violet waves which are shorter than natural light waves in a vacuum and thus to get a photograph of particles too short to be caught in ordinary light.” Here the doctor made his final drawing.

Ultra-violet waves:

“Thus a shadow thrown on a spark of an ultra-violet ray in a vacuum will be recorded on a photograph of the phenomenon. The discovery of the Becquerel Rays, the X-rays and the various rays known as “gamma,” etc., were all stepping stones to our knowledge of the tiniest particles. Compared with electrons, atoms and molecules, the colloid is relatively large.

“A photograph would show the presence of a colloid without great difficulty. Now, what is the relation of the colloid to the problem we are trying to solve? During the world war, things were learned which were mothered by necessity. Surgery had to be not only quick but effective. While what is known as the shock of an operation is due to a toxic condition, it is not what is technically known as blood poison. It is definitely the shock of the operation. In the world war it was learned that the shock of the operation was due to the absorption or infiltration of certain toxic or poisonous substances which belong to the colloid family.

“It was observed that if the haemostats were removed from a wounded member, which had been amputated, the condition of shock immediately was noticeable. This led to the conclusion that the haemostats kept out something which could enter when they were removed. The inevitable conclusion which followed was that the cause of shock was something which could not pass through an animal membrane or tissue, such as the walls of the blood vessels. Experiments have shown that while crystalline molecules would pass readily enough through a parchment filter the colloids remained behind.

“So, if a wound is made perfectly sterile and haemostats are used to seal the wound hermetically, the colloid poisons are excluded and, as they could not penetrate an animal membrane, the sealing of the wound effectually prevents the condition known as shock which so often is the fatal result of an operation. The tiny colloid, first known by its shadow on a spark, cannot enter the blood stream if the wound of amputation is sealed.

“The lessons of the world war showed that the wall cells of the blood vessels, the arteries, veins and capillaries present a compact and effective barrier to the passage of the colloidal poisons which cause death. Can you see now where we have arrived? Dr. Lawson has said that Mr. Craighead’s death was due to poisons which seeped in through the wall cells of the blood vessels. But in this long and perhaps tiresome explanation I have shown this to be impossible. Jim Craighead did not die of the shock of the operation. Dr. Lawson is positive that the wound was perfectly clean, that it was impossible for infection to have entered at the point of amputation.

“If it was impossible there, it was impossible elsewhere. So, if Jim Craighead did not die of the shock, he died of something else. It was not blood poison, for it would not have acted on a man of Craighead’s strength and perfect health, in so short a time. His death was due neither to blood poison nor to shock. Of what, then, did he die? Symptoms tell us clearly enough. Craighead’s son describes in untechnical language, symptoms which point almost unerringly to the fact that Craighead died of poison, administered to him. That poison, I assert was strychnine.”

Had a thunderbolt destroyed the cupola on a nearby building and caused it to crash in on them, or had a boy rushed in crying that a tidal wave was rushing up Broadway, the excitement could not have been greater. The girl was crushed. Was it guilt that could be read in her terrified features? The coroner’s jury, which a few minutes earlier was ready to render a verdict of death due to an operation, was now anxious to recommend the arrest of a murderer.

For a few seconds the atmosphere of the court room was tense—no whispers broke the silence, but eyes moved restlessly to the actors in the drama. The girl under guard, almost terror stricken, looked across beseechingly at her lover. The youth returned her gaze, nodding encouragingly. Every word spoken by the doctor had burned his soul. His steady, calm exterior encouraged the girl and she grew calmer.

This ominous silence was broken by the coroner.

“Dr. Jarvis,” he said, “the fact of poisoning can readily be established by an autopsy. If it reveals, as you assert, the presence of poison, arrests must follow.”

“Yes, if after the autopsy, you find the guilty one who, being warned, would flee,” cried the inspector, who had followed the conclusions of Dr. Jarvis and decided upon his course of action. “While you are looking for proofs which you are certain to find, if Dr. Jarvis is not mistaken, and he does not talk like a man who is mistaken, I will take the precaution of arresting Ross Craighead, on the charge of poisoning or being an accessory to the poisoning of his father.”

“What a foul lie!” cried the youth, leaping toward the inspector, with whom he would have grappled like a wild beast, had not the police interceded. After a violent struggle he was manacled so that he could threaten no more harm. The inspector was unmoved by this demonstration. He was calculating the girl must move. Either she would remain calm, as might be expected of Piggy Bill’s “sweetie,” or she would try to save Ross. His calculation was perfect. Ross had not yet been subdued when the girl’s voice could be heard above the tumult. Terror and dismay mingled in her cry. She rose to her feet and began to speak. An officer grasped her arm to force her back into her chair, but the inspector motioned him to release her. He spoke to her across the room.

“Whatever you say, Tessie, will be used against you,” he said. “Do you want to take the stand again? Perhaps you had better talk to a lawyer?

“No, no,” she cried wildly, “I will tell you everything I know. I did not understand what it all meant until Dr. Jarvis had explained. Now I see it all and it is too horrible. That boy you accuse, Ross—you do not know him. He couldn’t kill a rabbit. He would run his car off a bridge to keep from hitting a stray cat. He nearly wrecked us once to avoid hitting a dog. You can do anything to me if he is cleared. But I never committed murder. I can’t bear suffering in others—I suffer as much as the one I see in pain. But who is going to believe me, now?”

Slowly she moved to the witness box, where she took the oath again.

“Miss Prettyman,” said Mr. Bailey, “tell us all the facts you know in connection with Mr. Craighead’s death. Tell us particularly where you obtained any of the drugs administered to him during the period following his operation.”

“It is true,” Tessie began, “that I bought all the drugs which Mr. Craighead needed. All the prescriptions were filled by the Groves pharmacy. There were two or three for digitalis and one or two for antiseptic washes. There was another prescription which I must describe. The day before Mr. Craighead died I went to the prison to see Bill Hovey.”

The inspector whispered quickly to Mr. Bailey, beside whom he had taken a chair. The lawyer now saw his cue. The girl was to be sweated. In far harsher terms than the inspector used for the third degree, he shot out:

“How many times did you go to see this Bill Hovey?”

“Twice, the day before Mr. Craighead died,” she answered dully.

“Bill Hovey, in the parlance of the underworld, is your ‘sweetie,’ is he not?” pursued the lawyer.

“You filthy cad,” burst from Ross, who tried unavailingly to break his manacles.

“You’ll be gagged, if you don’t keep quiet,” said one of his guards. But the inspector turned and motioned for silence.

“Mr. Bailey,” replied the girl, with dignity and resentment, “Bill Hovey is a man who, I have learned lately, has committed many wrongs, but he is fifty-two years old and I am twenty-two. He never was my ‘sweetie,’ as you call him, since you are so well acquainted with the underworld; he is my stepfather.”

There was a murmur of approval from the spectators, who obviously did not like the way the examination was conducted. Inspector Craven leaned toward Dr. Jarvis.

“Say, Doc,” he whispered, “I’m beginning to see light. We’re only getting started. How about you?”

“Did Mr. Craighead and Ross Craighead know that your stepfather was in prison?” asked Mr. Bailey.

“When Ross Craighead first asked me to dinner at their home,” answered Tessie, “I knew that he was showing me serious attention. After dinner, I told Mr. Craighead that I had only come so that I could talk to him more freely than was possible in the office; I told him that my stepfather was a drug addict and in prison for having drugs; that he was an educated man, but of no account, and that he always had plenty of money, although we never knew him to work. Still he never was mean to us and I saw little of him after my mother died. Recently I had not seen him. The last time he saw me he told me he was not as ‘flush’ as he had been. All this I told Mr. Craighead, thanking him for his kindness. Then I intended to leave. But he and Ross refused to let me go at all. They said it was bad enough to have the father’s sins visited on the heads of their children, without taking in the stepchildren, too.”

Prompted by the Inspector, Mr. Bailey continued his questions.

“Why,” he asked, “did you go to see Bill Hovey the day before Mr. Craighead died?”

“I should not have gone at all,” replied Tessie, “if Mr. Craighead had not requested it. He sent me out a couple of times to a druggist with an old prescription for narcotics—morphine—and the druggist refused to fill it. He knew Dr. Lawson had forbidden it and was afraid. Then the pain got so bad that Mr. Craighead tossed about moaning all the time. His tossing only made the pain worse, so he called me early in the morning.

“‘Tessie,’ he said, ‘do you mind going to that no account stepfather of yours? Ask him if he can tell you where to get some morphine. Those fellows always know where it is to be had. Just say that you want to do me a good turn—that I am in great pain.’

“I asked Ross what to do. He said, ‘I don’t like it at all, but he never uses it unless he is suffering, so I guess it will be all right to humor him. He is always brooding over the loss of his foot, so a few hours of freedom from pain may do him good. He was like this when he sprained his ankle in a tennis game, two years ago. I thought he would go mad. He just drugged himself all the time to deaden the pain. The doctor said he took enough to kill a horse. I often feared he might get the habit, but he never did.’

“So, I went to see Bill Hovey at the prison. He seemed glad to see me and told me what an injustice had been done him. He said he felt sure he could get out if he had money enough to pay the lawyers. After he got out he intended to go off somewhere and start right again. I told him I was glad to hear it and then he said:

“‘Tessie, I could fix everything up if I had $10,000. You could get it, too, to help your father out of trouble.’

“‘How could I get such a sum?’ I asked.

“‘Why, your rich friends, Mr. Craighead and his son, they have all kinds of money—they would give you $10,000 if you tried them out.’

“‘If that is the price of asking you a favor, Bill Hovey,’ I answered, ‘I may as well go.’

“He changed, then—tried to soothe me—said he would do anything I wanted—asked me to forget what he had said. Then I asked him where I could get some morphine. I told him how Mr. Craighead was suffering, but that I was doing this of my own accord to help him. I didn’t want to tell Bill anything that might encourage him to try to get money from Mr. Craighead. He asked me when I was going to be married. I said I didn’t know—Mr. Craighead wanted us to wait until Ross was well on in the business, because Ross was to succeed him. He wanted him to learn the ‘ropes,’ from the beginning.

“‘Tessie,’ he said finally, ‘I’ll do this for you without any strings. I know of another drug that he can use with the morphine. It is called scopolamin and is known as a mydriatic. But it has other properties, too. Do you know anything about it?’

“‘No,’ I answered, I never studied much chemistry.’

“Bill wrote some words hastily. He said it was a prescription which I was to take to a place near Tarrytown.”

The moment the girl mentioned “Tarrytown,” two hard-faced men in the court room rose hastily from their seats, one moving toward the door, the other to a corner of the corridor where there was a telephone booth. But the inspector, who had followed the girl’s story with the utmost attention, was watching every one of the spectators in the crowded court room.

“Get those two men,” he ordered, pointing to the pair, who tried to force their way along more quickly. The second man actually entered the telephone booth, frantically moving the lever to signal the operator. An officer pounced on him before the operator had answered. He struggled mightily, but handcuffs were slipped on his wrists too quickly for resistance. His companion reached the door to walk into the arms of another officer.

Pandemonium now reigned in the court room. Two reporters rushed to the telephone booths. The police made no exception for the men of the press. For some minutes the confusion was too great for any voice to be heard. Finally the inspector succeeded in making himself heard, his big, booming tones dominating the uproar.

“Mr. Coroner,” he began, “nothing but the necessity of preventing a crafty scoundrel from making his escape could justify my interference with your jurisdiction. I am an officer sworn to uphold the dignity of your court as well as that of any other judge or official. But I knew, if there was a grain of truth in the story that young woman on the stand was telling, the villain certainly could not be without interest in this inquest. He would not dare to come himself, nor would he dare to remain ignorant of what might transpire. Some trusted agent must be present.”

“Will you continue your story, Miss Prettyman?” asked Mr. Bailey, with more courtesy than he had yet shown the girl.

In a firmer voice, inspired with the hope that her story was gaining credence, Tessie resumed her narrative.

“Bill wrote the prescription in words I could not understand. He said it was Latin. I studied a little Latin in school, but not that kind. He called it medical Latin; besides, the writing was very cramped and would have been hard to read even in English. The last part of it I could not make out at all.

“‘He’s an artist,’ said Bill, ‘this druggist you will visit—a man of parts, though deformed, yet in his art, a creature of meticulous skill. Fussy he is, too, about his prescriptions—he will always have them very proper and formal.’

“The prescription bore no address.

“‘Where must I take the prescriptions?’ I asked him.

“‘On 42nd Street,’ he said, ‘off Broadway, look for a taxicab, not one of the big companies—there is a coat of arms on the door, with a figure nine above it. Tell the driver Bill sent you with a prescription. He will take you to the place. It is a long ride, but you need have no fear.’

“I went to 42nd Street and Broadway, as Bill had told me, but I saw so many cars that I thought he had tricked me. None of the cars stood more than a few seconds. While I stood there bewildered, staring at the doors of all the taxis, one stopped opposite me. The driver motioned to me and then I noticed that the door had a coat of arms and a figure nine. The traffic was stopped for an instant. He opened the door for me to step in. The moment I was in he closed the door and drove off. At first I thought he was crazy, for he drove around the block three times, then went over to Sixth Avenue and drove almost recklessly. After that, he turned again two or three times and I recognized Broadway. We never left Broadway again until we reached Tarrytown. We passed a number of fine estates, and several towns, all new to me, for I had never been so far on that road before. But I did notice that we never turned until we had passed Tarrytown. Some distance beyond Tarrytown—it may have been a few miles—the driver took a turn to the left toward the river, until we came to quite a woods. It looked like part of some big estate that had not been well kept or from which its owner had been absent a long time. Weeds grew tall, the fences were broken and it looked quite deserted.

“A kind of wagon track led through a gate, which hung on one hinge, into the woods. The driver lifted the gate to let the car through, then closed it again behind him. Some distance from the road, well hidden in the trees, we came to a house, once a tenanted house, but now looking very dilapidated. It did not seem a likely place for a drug store—still I said nothing as my stepfather had directed.

“The car stopped and I stepped out. The driver knocked at the door twice, rather sharply. Some one peered through a dust-covered window half closed by rickety shutters. In a second or two the door opened, the driver mumbled a few words and we were ushered into a strange room by a misshapen dwarf.

“It was fitted up as a drug store—counters, shelves filled with bottles, all labeled, graduate glasses such as you see in the hospital, rolls of bandages, first aid kits and instruments. The druggist was a hunchback, who filled me with aversion. But he merely held out his hand for the prescription, turning his hand to his bottles and glasses as soon as I had given it to him. It was easy to see that he was a skilled apothecary by the way he handled everything. When he had filled the prescription he gave me a package. It contained a bottle of colorless liquid which was labelled: ‘Dose—ten drops with milk or other liquid.’ There was a small box, too, labelled ‘morphine.’ On the bottle was the word ‘scopolamin.’

“The driver was waiting outside the house for me. It seemed good to get out in the air again. Once in the taxicab, the driver backed in among the trees to turn around. He drove back along Broadway until he came to the city line. There he told me that I could return along the subway. All this mystery so puzzled me that I determined to see Bill again to learn if the prescription was properly filled. When I saw Bill Hovey I showed him the bottle. There were many bottles in his cell. He was known to be a good chemist and worked in the prison drug shop. He took this bottle and held it to the light. Then he took a sip of it. ‘Seems to be all right,’ he said. He wrapped up a bottle, but I know now, that he must have given me a different one. I put it in my pocket. From the prison I went straight to Mr. Craighead. Ross was with him. I said:

“‘Why all this round-about way to get a little drug? It was all horrible. I wish that you would not take any more of the stuff.’

“Mr. Craighead just laughed. ‘Well, little girl,’ he said, ‘if a man insists on buying liquor, he must go to rather ugly looking places to get it—if he must have morphine, and the doctors will not get it for him, he must go to even uglier places. But we will never try that again!’

“That night he took a hypodermic, but never touched the bottle. He kept all out of sight when Dr. Lawson came the next morning. Toward night his pain became intense again. That must have been why he used the drug the misshapen druggist had given me. If I had only known—oh, if I had only known.”

Tessie gave way to uncontrollable sobbing.

When she had grown somewhat composed, Mr. Bailey asked:

“Could you read the prescription at all?”

“One word, only,” replied Tessie, “Scopolamin.”

“What became of the prescription?”

“There was a file,” said Tessie, “with a number of other prescriptions filed upon it; the druggist put the one Bill had given me with the others.”

Half dazed by the ordeal through which she had passed, Tessie walked unhindered to where Ross sat manacled. Inspector Craven himself removed the handcuffs from the boy’s wrists. He drew the girl to a chair beside him.

“Mr. Coroner,” said Inspector Craven, rising, “I am prepared now to make the extraordinary request which I mentioned before Miss Prettyman had completed her testimony. There is but one way to test her story fairly. Assuming, as I do, that her story is true, she would be placed in jeopardy, if the men who tricked her were allowed to escape. It is possible to trap the druggist, who doubtless, with mind warped by affliction, is capable of aiding assassins who use poison. If the court is willing to hold this session open until I have had time to verify this extraordinary tale and capture, if possible, the author of a diabolical plot, several unexplained murders of the same sort may be solved. But in order that no warning may be given, I request you to make an order that no one leave this court room until I return.”

“It is an extraordinary request, Inspector Craven,” replied the coroner, “so extraordinary that I do not know if I have so much arbitrary power. Before even deciding I must ask you a question to clear up the young woman’s story. Is it possible that she visited this Hovey in prison and that it was possible for him to give her writing without detection?”

“When a man like Bill Hovey is captured, Mr. Coroner,” answered the inspector, “he is often given a great deal of apparent freedom in order that he may betray his confederates, and also in a narcotic case, that he may betray the hiding place of a lot of dangerous drugs. It was even contemplated to release Hovey and keep him under surveillance, but he is so slippery a character that the plan was abandoned as too risky. Two men were detailed to follow the young woman on her visit to Hovey. They were not clever enough for the job. The taxi driver went three times around the block with the officers two cars behind on his trail. The driver knew it. He drove around the block until he saw the traffic signal about to change. He dashed across the street while the officers waited until the signal was changed again. When they crossed the street the taxi they were following had disappeared. The taxi, as Miss Prettyman has related, did not return to the city that night. When she returned to the prison, the officers who were supposed to be watching her, were still looking for the taxicab, which they learned had turned into Broadway. This incident, however, will result in more stringent rules and curtailment of prisoners’ privileges.

“What I propose to do is this,” continued Inspector Craven. “I propose to take Tessie and Doctor Jarvis with me to Tarrytown. Unless he has been warned, the druggist will be awaiting news. Two men from this room are in custody. There may be others posted here. For that reason our mission will be futile if anyone is permitted to leave.”

“If I make such an order,” said the coroner, “your men will have to enforce it. No matter how you travel you cannot go to Tarrytown and back under five hours.”

“That is true, Mr. Coroner,” said the inspector, “yet this is worthy of consideration. In the last four years there have been seven unexplained murders through poisons which cannot be obtained without a prescription. Yet no prescriptions for those poisons have been found nor has the source of them been traced. Here we have two desperate men skilled in toxicology with a supply of dangerous substances.”

The coroner hesitated no longer. Rising from his chair, he pronounced his decree:

“As the presiding officer of this court I hereby enjoin and forbid any person to leave this courtroom until the return of Inspector Craven or until he has advised the Court from Tarrytown, which I require him to do the instant he has accomplished or failed to accomplish his mission.”

An additional detail of officers had arrived. There were a few murmurs against this exercise of autocratic power, yet the murmurs were soft, for there was no spectator of the unexpected turn of events in the courtroom, who did not want to be present at the denouement. Some openly believed the girl was lying. Others quite vehemently espoused her cause. Obviously the hours would not be dull in the court room until the party returned.

The girl, a picture of abject despair, sat at the side of her affianced lover, uncertain of a future which only a few days before seemed rosy with the dawn of hope. Turning to her, the inspector said:

“Tessie, you must show the way to the druggist near Tarrytown. It means freedom and vindication for you and Ross if we verify your words. Doctor, if we can find that prescription, it will need more Latin than I ever knew to decipher it. Ross, I think it is coming out right—as right as it can.”

To this Ross made no reply. He pressed Tessie’s hand in farewell, then the trio left the courtroom, hundreds of curious eyes following them. Some women whispered as Tessie passed them:

“Good luck, dearie!”

Inspector Craven, not daring to trust himself, as he remarked to the doctor, took one of his men along as chauffeur. He feared that he would drive too fast for safety. So he said to the officer:

“Tarrytown, Beronio, at the best you can get out of her.”

The automobile had a riot car siren, but it is safe to assert that no riot car ever ran like that one. There were few curves to make and with a few exceptions, the road was perfectly straight all the way.

The car could run at a speed of over sixty. It ran very nearly that the entire distance. As they raced along the highway, Tessie felt the universe slipping from her. The thought of what place in the world might be hers when this nightmare was over terrified her. The doctor read some of her thought from her expression and, trying to make her talk pointed out objects along the road—a difficult task, with the car dashing along so that telephone and telegraph posts almost resembled a picket fence. She replied in monosyllables. Finally he said:

“You mustn’t worry so much, my child. What is your anxiety, now?”

“Oh,” she cried, gulping to keep down a sob, “if the hunchback has taken alarm and gone away, what will become of Ross and me?”

“The shack will still be there, won’t it? That will confirm part of your story,” said the doctor.

These words bewildered the trembling young woman.

“You don’t believe, then, that I gave him poison deliberately?” she faltered.

“I would need more proof than we have now,” answered Dr. Jarvis.

To this enigmatic reply there was no response.

They were not long in reaching Tarrytown, where Inspector Craven turned to Tessie, saying:

“You had better keep your eyes open now for the place where you turned off the main road. The speedometer says 52 now; if your guess of the distance is accurate, we should run much slower.”

Beronio ran the car more slowly for three miles, but Tessie did not recognize the turn. Nearing four miles, as the inspector was beginning to be assailed by doubts, she said suddenly:

“Just beyond here, I remember, is the cross road. This gateway with the two stone lions at each side, opened as we passed—a car coming out delayed us for a moment. It should be less than a city block ahead.”

The inspector felt almost cheerful when, two hundred feet farther on, another road crossed their path.

“To the left, Beronio,” he ordered, “when you come to the trees take the wagon trail and go just a short distance.”

Inspector Craven said these words fatuously, like a man who has learned a lesson in which he has not the slightest belief, who has been told to memorize the first fifty lines and mumbles the words like a talking doll. They were all unnerved as the final test approached. Mentally, the inspector blamed the doctor who had led him into a fool journey like this. Tessie was in a panic, fearing the escape of the dwarf. Dr. Jarvis alone seemed unconcerned. His tall figure, erect and commanding, his lips compressed in a firm, straight, uncompromising line, expressed no doubt whatever. The car stopped. Doctor Jarvis was the first to get out. Inspector Craven was at his side in an instant. Beronio opened the crazily hanging gate and ran his car into the shelter of the trees.

“How far did you go into the woods, Tessie?” asked the inspector.

“Possibly four or five blocks,” replied the girl.

“Beronio, give the doctor your gun,” ordered Inspector Craven. “He may need it. Lead on Tessie, but go softly.”

The evening was coming on, the autumn air was cool and damp in the neglected woods, weedy, with thick undergrowth; it was difficult to think of a house of any sort there. Yet they followed the girl, breathlessly, almost treading on her heels. Five hundred yards they trudged along the winding path when Tessie stopped.

“Look,” she whispered, pointing to the right.

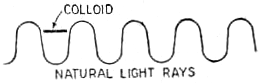

Both men followed her glance, seeing with relief a dilapidated tenant house, to all appearances unoccupied, save for an almost imperceptible thin line of smoke which was just visible above the broken edge of the chimney. The door was closed, but would probably offer no formidable obstacle. Shutters hung crazily over the one window which opened on the front of the house. They were half closed, held by a bit of soiled ribbon.

“Doc,” whispered the inspector, “I am going to slip over to the door. If anyone tries to drop out by that side window, use your gun. If any of Hovey’s gang is about, they won’t mince matters.”

Inspector Craven was himself, now. The house was here, that was certain. Stealthily he moved toward the door. Unperceived, he gained the doorway, where he stood for a moment listening for signs of life. Finally he heard a clinking of glass, a very faint tinkling. He put his big shoulder against the door. It was bolted and resisted his first assault. He thought no longer of who might be inside and with a mighty impact, burst the door open. As he almost fell over the threshold, a shot rang out and a twinge in the left shoulder told him it was a good shot. But he fired at the flash, which was followed by a cry of pain. He had hit his enemy in the gun arm. There was light enough for Craven to see a hunchback, who stood looking wickedly at the gun which covered him. The instant the reports rang out Doctor Jarvis and Tessie had run to the door of the shanty.

“Are you hurt, inspector?” asked Jarvis.

“He winged me in the left shoulder,” said Craven grimly. “If I had not stumbled when the door gave way it would have been worse, for it was well aimed for the heart. Pretty lookin’ bird, ain’t he? Is he the one who filled the prescription, Tessie?”

“Yes,” replied the girl, while the dwarf looked at her malevolently.

A small fire burned in an open stove. As the doctor, seeing the blood on Inspector Craven’s coat, began to examine him to learn the extent of his injury, the hunchback, with a quick movement, grasped a bundle of papers spiked on a file and threw them into the stove.

“The prescriptions, the prescriptions!” cried Tessie, in a panic.

Forgetting his wound, the inspector leaped at the hunchback, felling him to the floor with a heavy blow from the butt of his revolver. He sank to the floor, motionless. Doctor Jarvis had darted to the stove from which he retrieved the sheaf of papers, little the worse from the flames except where the hot coals had singed the edges. The doctor’s fingers suffered most from contact with the embers.

“Tessie,” said the inspector, nursing his wounded shoulder, “run through those papers. See if you can find anything that looks like the prescription Bill Hovey gave you.”

Eagerly enough, now, she lifted one sheet after another from the file. Not far from the top she came on one which she examined carefully.

“This is it,” she said, holding it out for Dr. Jarvis to read. His professional instincts, however, overcame his curiosity.

“Inspector,” he cried, somewhat shamefacedly, remorseful for neglect toward a wounded friend, “let us have a look at that shoulder first.”

“It hurts like the devil,” said Inspector Craven, “but that bird is stirring, so safety first. Take a pair of handcuffs out of my pocket and snap them on his wrists. He would blow us all up and himself, too, if he got the chance.”

Dr. Jarvis secured the misshapen dwarf, clumsily enough, then looked at his wound. The dwarf’s arm was bleeding. Without too great delay, for he was much more worried over the inspector than over the misshapen druggist, he bound the wound tightly to prevent further bleeding. In all this commotion, although he stirred, the man did not regain consciousness. He had been dealt a stiff blow.

The inspector was not seriously wounded. The bullet fired by the hunchback, from a vicious little automatic .25 had gone straight through the shoulder muscles, severing the smaller blood vessels. It was a matter of a few minutes to dress the wound, but Craven was impatient to learn the truth. Had they found the prescription? If they had, his wound mattered little. If not, he was a fool. He had made a melodrama of a coroner’s investigation. If without cause, he was a zany. With cause, he preserved his self-respect at least.

“Doc,” he said, as soon as the bandage was drawn tight and a tourniquet applied, “see what kind of a fist Piggy Bill writes. If it’s the literature the little lady says, I’ll bet it against Shakespeare.”

Doctor Jarvis then spread the paper Tessie had given him on the counter, while Tessie and the inspector leaned over his shoulder.

“The first paragraph calls for morphine and scopolamin,” said he. “But scopolamin has no virtue in a surgical case. But wait,” he added, “there is more. My God, what infamy!”

For a moment he was speechless, then began reading words incomprehensible to his hearers.

“Monsieur et cher ami:” was the salutation, then came the following words: “C’est bien drôle que le mot ‘scopolamin’ et le mot qui exprime l’extrait de la noix vomique ont la meme total; il serait bien dommage si l’on prendrait l’un pour l’autre.”

“What does it all mean?” asked Inspector Craven.

“Well,” answered the doctor, “it is not medical Latin nor any other kind of Latin. It is written in fairly good French, not at all difficult to follow. This is how it reads: ‘My dear friend: it is very curious that the word “scopolamin” and the word which signifies the extract of nux vomica have the same number of letters. It would be sad if one mistook the one for the other.’

“That was why he told Tessie scopolamin would help Craighead. It happened to have the same number of letters the way he spelled it (without the ‘e’) as strychnine. Strychnine is an alkaloid of nux vomica. He knew Tessie was ignorant of French—the rest was easy. But I don’t understand what he hoped to gain by it.”

“What, a hard-boiled guy like that?” shouted the inspector. “Hell, he needed $10,000. If Tessie got married he would send for her and tell the story counting on her fear to see that he got enough to pay the lawyer who guaranteed to get him out. Why, this bunch saw Tessie paying blackmail for murder the next ten years.” Then turning to the girl, he continued:

“Tessie, you have our compliments. I hope fortune will smile on you. This has been a terrible ordeal for a young girl.”

“Indeed,” sobbed the girl, as reaction set in, “I do not care about fortune, now. How can I live, knowing that I helped kill my benefactor, the one who was as much a father to me as my own might have been had he lived.”

The doctor took the bundle of prescriptions and with a number of vials containing prohibited drugs, narcotics and toxic substances, they returned to the car, the doctor forcing the hideous looking dwarf to walk beside him. They found his name to be Timothy Clegg, from one of the prescriptions. He was bundled into the car and the return journey to the metropolis began. At Tarrytown, the inspector stopped long enough to have a couple of officers sent to guard the drug store hidden in the woods, so that no evidence might be destroyed. In the prescriptions were enough orders for deadly poisons, signed by Piggy Bill Hovey, to damn him many times over. The proof in the Craighead case was convincing.

Inspector Craven then telephoned the coroner of the success of their mission. Beronio returned to town in more leisurely fashion. When they arrived at the Coroner’s Court with their prisoner and the inspector showing the evidences of a battle, the scene that followed beggared all description. Handcuffed and heavily guarded, the dwarf sullenly glared at his captors. Inspector Craven, despite his wound, took the stand. He described their journey in complete detail, verifying Tessie’s story. Calls for order failed to check the applause for the girl.

Dr. Jarvis followed the inspector. He identified the prescription, and gave its hideous import so vividly that the spectators shuddered. The jury took but a few minutes to render a verdict.

As the verdict was announced, a finely dressed woman murmured audibly:

“What a monstrous injustice! That young man inherits all his father’s wealth, although he helped to kill him.”

She was one of Jim Craighead’s numerous cousins and chagrined that his big estate was beyond her reach. Ross Craighead was too far away to hear her remark, but she heard his reply breathlessly, for he rose to his feet, before the crowd, dazed by the rapid turn of events. He took hold of Tessie’s arm, and stood near the coroner.

“I want to say to you, Mr. Coroner, publicly,” he began, “to Dr. Jarvis and to Inspector Craven, that after what has been revealed here today, it is impossible for me to take one penny from my father’s estate. His will makes Dr. Jarvis executor and gives him certain powers of distribution, in case I, for any reason, do not succeed to the property. Since I, however innocently, was, with Tessie, the instrument of his death, the money would come to me stained with blood. Yet this tragedy has knitted the fate of Tessie and myself in an indissoluble way. With what we have, we leave this city tonight—we shall be married at once. Then we shall go far from this place of dreadful memories to live as best we can, what life has in store for us. If we are free, we will go at once.”

“You are free,” said the coroner. “All the evidence is now on record.”

The crowd moved aside to let them pass. As they moved toward the door, the girl clutched with both hands, the arm of her partner in crime. Unwilling criminals!

The dwarf was never tried. He was found dead in his cell the next morning, despite the careful guard set to prevent his suicide. A small capsule in his mouth showed that he was always prepared for the possibility of capture. Piggy Bill died mysteriously before any charge was presented against him. “Suicide,” remarked Inspector Craven, “as Webster once said, is confession.”

A year later, Dr. Jarvis received an announcement from Sydney, Australia, telling of the birth of “Jim Craighead, Second,” “a wonderful, blond boy, healthy and noisy.” The doctor smiled as he recalled that his power of appointment had not been exercised.

Transcriber’s Note: This story appeared in the August 1927 issue of Amazing Stories Magazine.