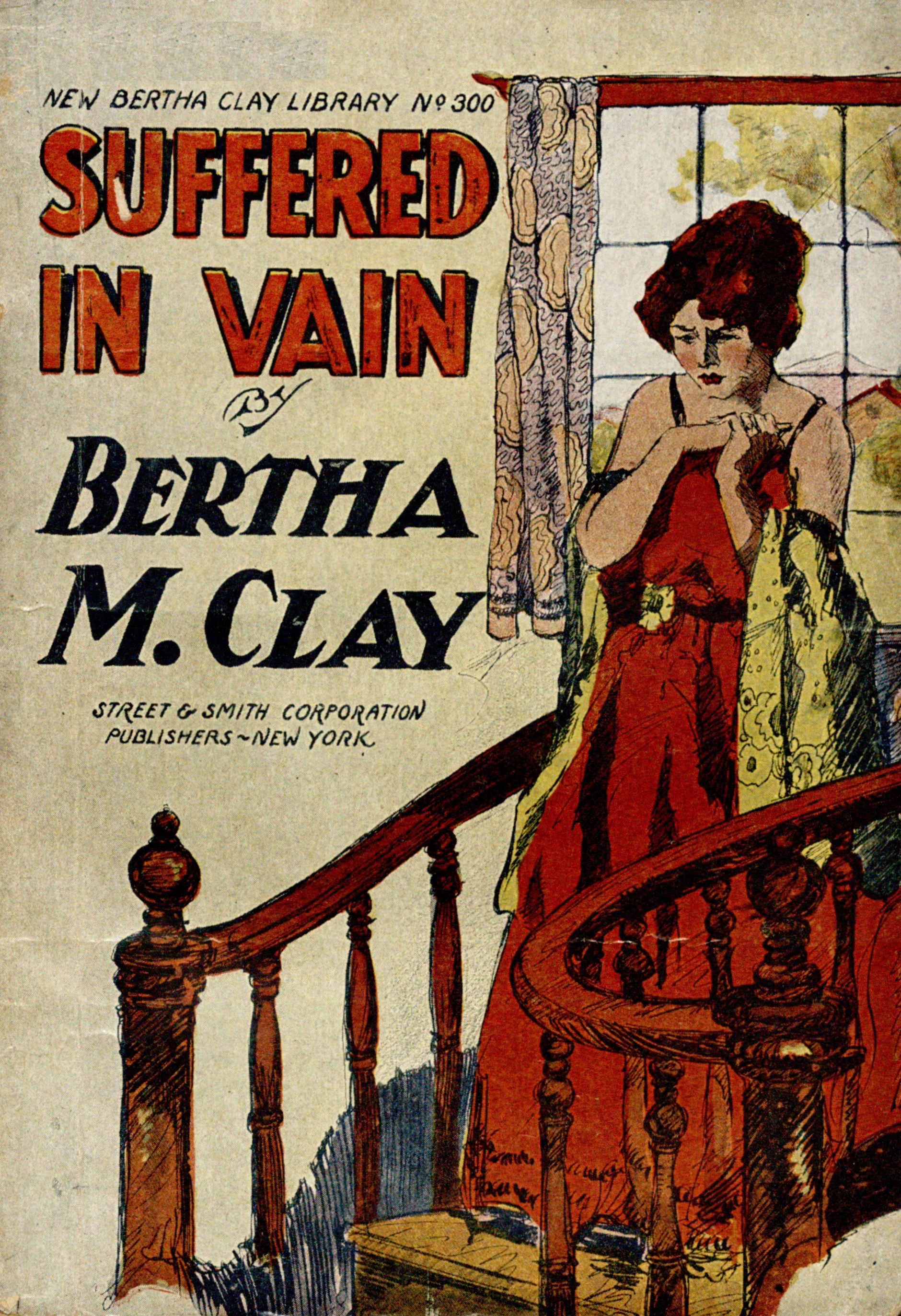

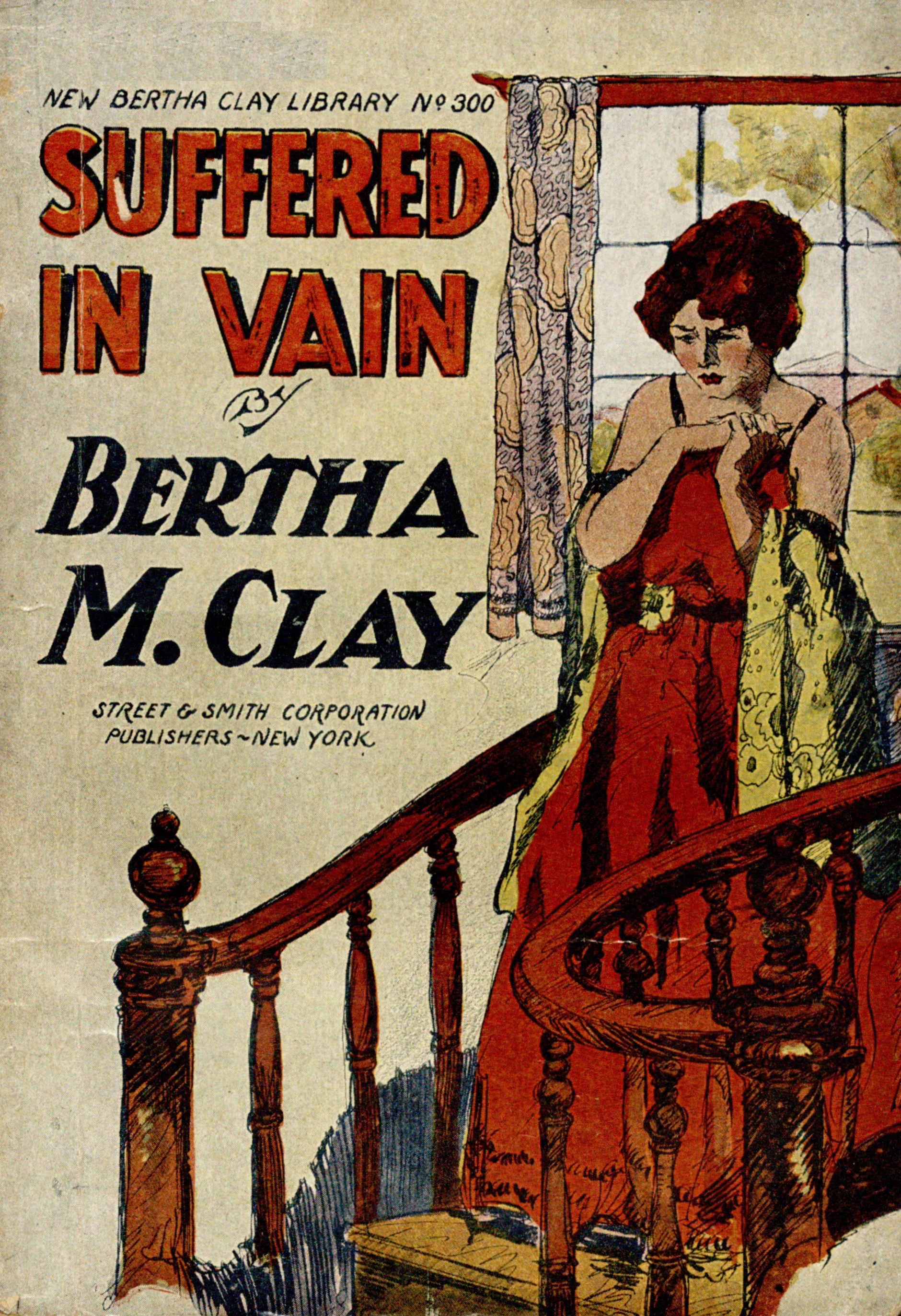

NEW BERTHA CLAY LIBRARY No. 300

By

Bertha

M. Clay

STREET & SMITH CORPORATION

PUBLISHERS ~ NEW YORK

A FAVORITE OF MILLIONS

ALL BY BERTHA M. CLAY

Love Stories with Plenty of Action

The Author Needs No Introduction

Countless millions of women have enjoyed the works of this author. They are in great demand everywhere. The following list contains her best work, and is the only authorized edition.

These stories teem with action, and what is more desirable, they are clean from start to finish. They are love stories, but are of a type that is wholesome and totally different from the cheap, sordid fiction that is being published by unscrupulous publishers.

There is a surprising variety about Miss Clay’s work. Each book in this list is sure to give satisfaction.

ALL TITLES ALWAYS IN PRINT

1—In Love’s Crucible

2—A Sinful Secret

3—Between Two Loves

4—A Golden Heart

5—Redeemed by Love

6—Between Two Hearts

7—Lover and Husband

8—The Broken Trust

9—For a Woman’s Honor

10—A Thorn in Her Heart

11—A Nameless Sin

12—Gladys Greye

13—Her Second Love

14—The Earl’s Atonement

15—The Gypsy’s Daughter

16—Another Woman’s Husband

17—Two Fair Women

18—Madolin’s Lover

19—A Bitter Reckoning

20—Fair But Faithless

21—One Woman’s Sin

22—A Mad Love

23—Wedded and Parted

24—A Woman’s Love Story

25—’Twixt Love and Hate

26—Guelda

27—The Duke’s Secret

28—The Mystery of Colde Fell

29—Beyond Pardon

30—A Hidden Terror

31—Repented at Leisure

32—Marjorie Deane

33—In Shallow Waters

34—Diana’s Discipline

35—A Heart’s Bitterness

36—Her Mother’s Sin

37—Thrown on the World

38—Lady Damer’s Secret

39—A Fiery Ordeal

40—A Woman’s Vengeance

41—Thorns and Orange Blossoms

42—Two Kisses and the Fatal Lilies

43—A Coquette’s Conquest

44—A Wife’s Judgment

45—His Perfect Trust

46—Her Martyrdom

47—Golden Gates

48—Evelyn’s Folly

49—Lord Lisle’s Daughter

50—A Woman’s Trust

51—A Wife’s Peril

52—Love in a Mask

53—For a Dream’s Sake

54—A Dream of Love

55—The Hand Without a Wedding Ring

56—The Paths of Love

57—Irene’s Vow

58—The Rival Heiresses

59—The Squire’s Darling

60—Her First Love

61—Another Man’s Wife

62—A Bitter Atonement

63—Wedded Hands

64—The Earl’s Error and Letty Leigh

65—Violet Lisle

66—A Heart’s Idol

67—The Actor’s Ward

68—The Belle of Lynn

69—A Bitter Bondage

70—Dora Thorne

71—Claribel’s Love Story

72—A Woman’s War

73—A Fatal Dower

74—A Dark Marriage Morn

75—Hilda’s Lover

76—One Against Many

77—For Another’s Sin

78—At War with Herself

79—A Haunted Life

80—Lady Castlemaine’s Divorce

81—Wife in Name Only

82—The Sin of a Lifetime

83—The World Between Them

84—Prince Charlie’s Daughter

85—A Struggle for a Ring

86—The Shadow of a Sin

87—A Rose in Thorns

88—The Romance of the Black Veil

89—Lord Lynne’s Choice

90—The Tragedy of Lime Hall

91—James Gordon’s Wife

92—Set in Diamonds

93—For Life and Love

94—How Will It End?

95—Love’s Warfare

96—The Burden of a Secret

97—Griselda

98—A Woman’s Witchery

99—An Ideal Love

100—Lady Marchmont’s Widowhood

101—The Romance of a Young Girl

102—The Price of a Bride

103—If Love Be Love

104—Queen of the County

105—Lady Ethel’s Whim

106—Weaker than a Woman

107—A Woman’s Temptation

108—On Her Wedding Morn

109—A Struggle for the Right

110—Margery Daw

111—The Sins of the Father

112—A Dead Heart

113—Under a Shadow

114—Dream Faces

115—Lord Elesmere’s Wife

116—Blossom and Fruit

117—Lady Muriel’s Secret

118—A Loving Maid

119—Hilary’s Folly

120—Beauty’s Marriage

121—Lady Gwendoline’s Dream

122—A Story of an Error

123—The Hidden Sin

124—Society’s Verdict

125—The Bride from the Sea and Other Stories

126—A Heart of Gold

127—Addie’s Husband and Other Stories

128—Lady Latimer’s Escape

129—A Woman’s Error

130—A Loveless Engagement

131—A Queen Triumphant

132—The Girl of His Heart

133—The Chains of Jealousy

134—A Heart’s Worship

135—The Price of Love

136—A Misguided Love

137—A Wife’s Devotion

138—When Love and Hate Conflict

139—A Captive Heart

140—A Pilgrim of Love

141—A Purchased Love

142—Lost for Love

143—The Queen of His Soul

144—Gladys’ Wedding Day

145—An Untold Passion

146—His Great Temptation

147—A Fateful Passion

148—The Sunshine of His Life

149—On with the New Love

150—An Evil Heart

151—Love’s Redemption

152—The Love of Lady Aurelia

153—The Lost Lady of Haddon

154—Every Inch a Queen

155—A Maid’s Misery

156—A Stolen Heart

157—His Wedded Wife

158—Lady Ona’s Sin

159—A Tragedy of Love and Hate

160—The White Witch

161—Between Love and Ambition

162—True Love’s Reward

163—The Gambler’s Wife

164—An Ocean of Love

165—A Poisoned Heart

166—For Love of Her

167—Paying the Penalty

168—Her Honored Name

169—A Deceptive Lover

170—The Old Love or New?

171—A Coquette’s Victim

172—The Wooing of a Maid

173—A Bitter Courtship

174—Love’s Debt

175—Her Beautiful Foe

176—A Happy Conquest

177—A Soul Ensnared

178—Beyond All Dreams

179—At Her Heart’s Command

180—A Modest Passion

181—The Flower of Love

182—Love’s Twilight

183—Enchained by Passion

184—When Woman Wills

185—Where Love Leads

186—A Blighted Blossom

187—Two Men and a Maid

188—When Love Is Kind

189—Withered Flowers

190—The Unbroken Vow

191—The Love He Spurned

192—Her Heart’s Hero

193—For Old Love’s Sake

194—Fair as a Lily

195—Tender and True

196—What It Cost Her

197—Love Forevermore

198—Can This Be Love?

199—In Spite of Fate

200—Love’s Coronet

201—Dearer Than Life

202—Baffled by Fate

203—The Love that Won

204—In Defiance of Fate

205—A Vixen’s Love

206—Her Bitter Sorrow

207—By Love’s Order

208—The Secret of Estcourt

209—Her Heart’s Surrender

210—Lady Viola’s Secret

211—Strong in Her Love

212—Tempted to Forget

213—With Love’s Strong Bonds

214—Love, the Avenger

215—Under Cupid’s Seal

216—The Love that Blinds

217—Love’s Crown Jewel

218—Wedded at Dawn

219—For Her Heart’s Sake

220—Fettered for Life

221—Beyond the Shadow

222—A Heart Forlorn

223—The Bride of the Manor

224—For Lack of Gold

225—Sweeter than Life

226—Loved and Lost

227—The Tie that Binds

228—Answered in Jest

229—What the World Said

230—When Hot Tears Flow

231—In a Siren’s Web

232—With Love at the Helm

233—The Wiles of Love

234—Sinner or Victim?

235—When Cupid Frowns

236—A Shattered Romance

237—A Woman of Whims

238—Love Hath Wings

239—A Love in the Balance

240—Two True Hearts

241—A Daughter of Eve

242—Love Grown Cold

243—The Lure of the Flame

244—A Wild Rose

245—At Love’s Fountain

246—An Exacting Love

247—An Ardent Wooing

248—Toward Love’s Goal

249—New Love or Old?

250—One of Love’s Slaves

251—Hester’s Husband

252—On Love’s Highway

253—He Dared to Love

254—Humbled Pride

255—Love’s Caprice

256—A Cruel Revenge

257—Her Struggle with Love

258—Her Heart’s Problem

259—In Love’s Bondage

260—A Child of Caprice

261—An Elusive Lover

262—A Captive Fairy

263—Love’s Burden

264—A Crown of Faith

265—Love’s Harsh Mandate

266—The Harvest of Sin

267—Love’s Carnival

268—A Secret Sorrow

269—True to His First Love

270—Beyond Atonement

271—Love Finds a Way

272—A Girl’s Awakening

273—In Quest of Love

274—The Hero of Her Dreams

275—Only a Flirt

276—The Hour of Temptation

277—Suffered in Silence

278—Love and the World

279—Love’s Sweet Hour

280—Faithful and True

281—Sunshine and Shadow

282—For Love or Wealth?

283—Love of His Youth

284—Cast Upon His Care

285—All Else Forgot

286—When Hearts Are Young

287—Her Love and His

288—Her Sacred Trust

289—While the World Scoffed

In order that there may be no confusion, we desire to say that the books listed below will be issued during the respective months in New York City and vicinity. They may not reach the readers at a distance promptly, on account of delays in transportation.

To be published In July, 1926.

290—The Heart of His Heart

291—With Heart and Voice

To be published in August, 1926.

292—Outside Love’s Door

293—For His Love’s Sake

To be published in September, 1926

294—And This Is Love!

295—When False Tongues Speak

To be published in October, 1926.

296—That Plain Little Girl

297—A Daughter of Misfortune

To be published in November, 1926.

298—The Quest of His Heart

299—Adrift on Love’s Tide

To be published in December, 1926.

300—Suffered in Vain

301—Her Heart’s Delight

302—A Love Victorious

[Pg 2]

ROMANCES THAT PLEASE MILLIONS

ALL BY RUBY M. AYRES

This Popular Writer’s Favorites

There is unusual charm and fascination about the love stories of Ruby M. Ayres that give her writings a universal appeal. Probably there is no other romantic writer whose books are enjoyed by such a wide audience of readers. Her stories have genuine feeling and sentiment, and this quality makes them liked by those who appreciate the true romantic spirit. In this low-priced series, a choice selection of Miss Ayres’ best stories is offered.

In order that there may be no confusion, we desire to say that the books listed below will be issued during the respective months in New York City and vicinity. They may not reach the readers at a distance promptly, on account of delays in transportation.

To be published in July, 1926.

| 1 | — | Is Love Worth While? | By Ruby M. Ayres |

| 2 | — | The Black Sheep | By Ruby M. Ayres |

To be published in August, 1926.

| 3 | — | The Waif’s Wedding | By Ruby M. Ayres |

| 4 | — | The Woman Hater | By Ruby M. Ayres |

| 5 | — | The Story of an Ugly Man | By Ruby M. Ayres |

To be published in September, 1926.

| 6 | — | The Beggar Man | By Ruby M. Ayres |

| 7 | — | The Long Lane to Happiness | By Ruby M. Ayres |

To be published in October, 1926.

| 8 | — | Dream Castles | By Ruby M. Ayres |

| 9 | — | The Highest Bidder | By Ruby M. Ayres |

To be published in November, 1926.

| 10 | — | Love and a Lie | By Ruby M. Ayres |

| 11 | — | The Love of Robert Dennison | By Ruby M. Ayres |

To be published in December, 1926.

| 12 | — | A Man of His Word | By Ruby M. Ayres |

| 13 | — | The Master Man | By Ruby M. Ayres |

[Pg 3]

OR,

A PLAYTHING OF FATE

BY

BERTHA M. CLAY

Whose complete works will be published in this, the New Bertha Clay Library

Printed in the U. S. A.

STREET & SMITH CORPORATION

PUBLISHERS

79-89 Seventh Avenue, New York

[Pg 5]

CHAPTER I. A SINGULAR WILL.

CHAPTER II. CAPTAIN DESFRAYNE’S PERPLEXITY.

CHAPTER III. LOIS TURQUAND’S EMBARRASSMENT.

CHAPTER IV. LOIS TURQUAND’S ALTERED FORTUNE.

CHAPTER V. A TRIPLE BONDAGE.

CHAPTER VI. PAUL’S GALLING SHACKLES.

CHAPTER VII. AN UNINTENTIONAL CUT.

CHAPTER VIII. THE NEW VALET.

CHAPTER IX. PLAYING AT CROSS-PURPOSES.

CHAPTER X. BUILDING ON SAND.

CHAPTER XI. PAUL DESFRAYNE’S WIFE.

CHAPTER XII. THE PRIMA DONNA’S HATE.

CHAPTER XIII. PAUL DESFRAYNE’S CONFESSION.

CHAPTER XIV. FRANK AMBERLEY’S EXULTATION.

CHAPTER XV. THE MISTRESS OF FLORE HALL.

CHAPTER XVI. GILARDONI’S LOVE-GIFT.

CHAPTER XVII. IN THE THUNDER-STORM.

CHAPTER XVIII. PAUL DESFRAYNE’S REFLECTIONS.

CHAPTER XIX. BLANCHE DORMER’S SURPRISE.

CHAPTER XX. THE BREAK OF DAWN.

CHAPTER XXI. LEONARDO GILARDONI’S STORY.

CHAPTER XXII. A VISION OF FREEDOM.

CHAPTER XXIII. THE EXPRESS TO LONDON.

CHAPTER XXIV. FRANK AMBERLEY’S ADVICE.

CHAPTER XXV. THE FIGURE ROBED IN BLACK.

CHAPTER XXVI. LUCIA GUISCARDINI’S DIAMOND RING.

CHAPTER XXVII. FRANK AMBERLEY’S MISSION.

CHAPTER XXVIII. THE INLAID CABINET.

CHAPTER XXIX. DEFIANCE, NOT DEFENSE.

CHAPTER XXX. FREE AT LAST.

CHAPTER XXXI. LUCIA’S TEARS.

CHAPTER XXXII. LUCIA GUISCARDINI’S MADNESS.

CHAPTER XXXIII. THE SOUND OF WEDDING-BELLS.

A SINGULAR WILL.

Always more or less subdued in tone and tranquil of aspect, the eminently genteel Square of Porchester is, perhaps, seen in its most benign mood in the gently falling shadows of a summer’s twilight.

The tall houses begin slowly, very slowly, to twinkle with a glowworm irradiance from the drawing-rooms to the apartments on the upper floors as the darkness increases. From the open windows float the glittering strains of Gounod, Offenbach, Hervé, fluttering down over the flower-wreathed balconies into the silent street beneath, each succession of chords tumbling like so many fairies intoxicated with the spirit of music. At not infrequent intervals, sparkling broughams whirl past, carrying ladies arrayed obviously for dinner-party, soirée, or opera, in gay toilets, only half-concealed by the loose folds of soft wraps.

At the moment the curtain rises, two persons of the drama occupy this stage.

One is an individual of a peculiarly unattractive exterior—a man of probably some two or three and thirty years of age—a foreigner, by his appearance. It would have been difficult to tell whether recent illness or absolute want had made his not unhandsome face so white and pinched, and caused the shabby garments to hang about his tall, well-knit figure. Seemingly, he was one of those most forlorn of creatures—a domestic servant out of employ.

The expression on his countenance just now, as he[Pg 6] leaned against the iron railings of the enclosure, almost concealed behind a doctor’s brougham which awaited its master, was not pleasant to regard. Following the direction of his fixed stare, the eye was led to a superbly beautiful woman, sitting half-within the French window of a drawing-room opposite, half-out upon the balcony, among some clustering flowers.

This woman was undoubtedly quite unconscious of the steady attention bestowed upon her by the solitary being, only distant from her presence by a few feet. She was a young woman of about three-and-twenty—an Italian, judging by her general aspect—attired in a rich costume, lavishly trimmed with black lace. A white lace shawl, lightly thrown over her shoulders, permitted only gracious and flowing outlines to reveal themselves; but her supremely lovely face, the masses of coiled and plaited hair, dark as night, stray diamond stars gleaming here and there, the glowing complexion, the sleepy, long, silk, soft lashes, resting upon cheeks which might be described as “peachlike,” the crimson lips, the delicately rounded chin, the perfect, shell-like ears, made up an ensemble of haunting beauty that, once seen, could never be forgotten.

Of the vicinity, much less of the rapt gaze of the wayfarer lingering yonder, she was profoundly ignorant, her attention being entirely occupied by a written sheet of paper, held between her slender white fingers. This she was apparently studying with absorbed interest.

The loiterer clenched his fist, malignant hate wrinkling his care-worn face, and made a gesture, betraying the most intense anger toward the imperial creature in the amber and black draperies.

“So, Madam Lucia Guiscardini,” he muttered, under his breath, “you bask up there, in your beauty and your finery, like some sleek, treacherous cat! Beautiful signora, if I had a pistol now, I could shoot you dead, without leaving you a moment to think upon your sins. Your sins! and they say you are one of the best and noblest of women—those who do not know your cold and cruel heart, snow-plumaged swan of Firenze! How can it be that I could ever have loved you so wildly—that I could[Pg 7] have knelt down to kiss the ground upon which your dainty step had trod? Were you the same—was I the same? Has all the world changed since those days?

“I have suffered cold and hunger, sickness and pain, weariness of body, anguish of mind, while you have been lapped in luxury. You have been gently borne about in your carriage, wrapped in velvets and furs, or satins and laces, while I—I have passed through the rain-sodden streets with scarcely a shoe to my foot. They say you refused, in your pride, to marry a Russian prince the other day. All the world marveled at your insolent caprice. I wonder what you think of me, or if you ever honor me with a flying recollection? Am I the one drop of gall in your cup of nectar, or have you forgotten me?”

A quick, firm step startled the tranquil echoes of the square, and made this fellow glance about with the vague sense of ever-recurring alarm which poverty and distress engender in those unaccustomed to the companionship of such dismal comrades.

The instant he descried the person approaching, his countenance changed. He cast down his fierce, keen eyes, and an expression of humility replaced the glare of vindictive bitterness that had previously rendered his visage anything but pleasant to look upon.

This third personage of the drama was one, in appearance, worthy to take the part of hero. He was, perhaps, about thirty years old, with a noble presence, a fair and frank face, though one clouded by a strange shadow of mysterious care ever brooding. The face attracted at once, and inspired a wish to know something more of the soul looking through those bright, half-sadly smiling violet eyes as from the windows of a prison.

The forlorn watcher next the iron railings left his post of stealthy observation on seeing this gentleman, and, crossing, so as to intercept him, stood in the middle of the pavement in such a way as to abruptly bar the passage.

The large kindly eyes, which had been cast down, as if indifferent to all outward things, and engaged in painful introspection, were suddenly raised with a flash of displeased surprise.

[Pg 8]

“Sir,” began the poor lounger deprecatingly, half-unconsciously clasping his meager hands, and speaking almost in the voice of a supplicant, “Captain Desfrayne, forgive me for daring to address you; but——”

“You are a stranger to me, although you seem acquainted with my name,” the gentleman said, scanning him with a keen glance. “I don’t know that I have ever seen you before. What do you want? By your accent, you appear to be an Italian.”

“I am so, captain. I did not know you were coming this way, nor did I know you were in London. I have only this moment seen you, as you turned into the square; or I—I thought—for I know you, though perhaps you may never have noticed me—I knew of old that you have a kind and tender heart, and I thought—— Sir, I am a bad hand at begging; but I am sorely, bitterly in need of help.”

“Of help?” repeated Captain Desfrayne, still looking at him attentively. “Of what kind of help?”

Those bright eyes saw, although he asked the question, that the man required succor in any and in every shape.

“Sir, when I knew you, about three years ago, I was in the service of the Count di Venosta, at Padua, as valet.”

“I knew the count well, though I have no recollection of you,” said Captain Desfrayne. “Go on.”

“He died about a year and a half ago. I nursed him through his last illness, and caught the fever of which he died. I had a little money—my savings—to live on for a while; but all is gone now, and I don’t know which way to turn, or whither to look for another situation. It was with the hope of finding some friends that I came to London; I might as well be in the Great Desert.”

“I have no doubt your story is perfectly true; but I don’t see what I can do for you,” Captain Desfrayne said, with some pity. “However, I will consider, and, if you like to come and see me to-morrow, perhaps I—— What is your name?”

“Leonardo Gilardoni, sir.”

The hungry, eager eyes watched as Captain Desfrayne[Pg 9] took a note-book from his pocket and scribbled down the name, adding a brief memorandum besides.

The sound of these men’s voices speaking just beneath her window had failed to attract the attention of the beautiful creature in the balcony. But now, when a sudden silence succeeded, she looked over from an undefined feeling of half-unconscious interest or curiosity.

As she glanced carelessly down at the two figures, the expression on her face utterly changed. The great eyes, the hue of black velvet, opened widely, as if from terror, or an astonishment too stupendous to be controlled. For a moment she seemed unable to withdraw her gaze, fascinated, apparently.

The little white hands were fiercely clenched; and if glances could kill, those two men would have rapidly traversed the valley of the shadow of death.

Fortunately, glances, however baleful, fall harmless as summer lightning; and the interlocutors remained happily ignorant of the absorbed attention wherewith they were favored.

In a moment or two she rose, and, standing just within the room, clutching the curtain with a half-convulsive grip, peered down malevolently into the street.

“What can have brought these two men here together?” she muttered. “Do they come to seek me? I did not know they were conscious of one another’s existence. What are they doing? Why are they here? Accursed be the day I ever saw the face of either!”

The visage, so wondrously beautiful in repose, looked almost hideous thus distorted by fury.

She saw Captain Desfrayne put his little note-book back in his pocket, and then heard him say:

“If you will come to me about—say, six or seven o’clock to-morrow evening, at my chambers in”—she missed the name of the street and the number, though she craned her white throat forward eagerly—“I will speak further to you. Do not come before that time, as I shall be absent all day.”

With swift, compassionate fingers he dropped a piece of gold into the thin hand of the unhappy, friendless man before him, and then moved, as if to continue his way.

[Pg 10]

The superb creature above craned out her head as far as she dared, to watch the two. Captain Desfrayne, however, seemed to be the personage she was specially desirous of following with her keen glances. To her amazement and evident consternation, he walked up to the immediately adjacent house, and rang the bell. The door opened, and he disappeared.

The shabby, half-slouching figure of the supplicant for help shuffled off in the other direction, toward Westbourne Grove, and vanished from out the square.

Releasing her grip of the draperies hanging by the window, the proud and insolent beauty began walking up and down the room, flinging away the paper from which she had been studying.

She looked like some handsome tigress, cramped up in a gilded cage, as she paced to and fro, her dress trailing along the carpet in rich and massive folds. Some almost ungovernable fit of passion appeared to have seized upon her, and she gave way to her impulses as a hot, undisciplined nature might yield.

There was a strange kind of contrast between the feline grace of her movements, the faultless elegance of her perfect toilet, the splendor of her beauty, and the untutored violence of her manner.

“What do they want here?” she asked, half-aloud. “Why do they come here, plotting under my windows? Do they defy me? Do they hope to crush me? What has Paul Desfrayne to complain of? I defy him, as I do Leonardo Gilardoni! Let them do their worst! What are they going to do? Has Leonardo Gilardoni found any—any——”

She started back and looked round with a guilty terror, as if she dared not think out the half-spoken surmise even to herself.

“He knows nothing—he can know nothing; and he has no longer any hold on me,” she muttered presently; “unless—unless the other has told him; and I don’t believe he would trust a fellow like him: for Paul Desfrayne is as proud as Lucifer. Oh, if I could but live my life over again! What mistakes—what fatal mistakes I have made—mistakes which may yet bring ruin[Pg 11] as their fruit! I will leave England to-morrow. I don’t care what they say, or think, or what loss it may cost to myself or any one else. Yet, am I safer elsewhere? I know not. What would be the consequences if they could prove I had done what I have done? I know not; I have never had the courage to ask.”

Totally unconscious of the vicinity of this beautiful, vindictive woman, Captain Desfrayne tranquilly passed into the house which he had come to visit.

“Can I see Mrs. Desfrayne?” he inquired of the smart maid servant who answered his summons.

“I will see, sir. She was at dinner, sir, and I don’t think she has gone out yet.”

The beribboned and pretty girl, throwing open the door of a room at hand, and ushering the visitor within, left him alone, while she flitted off in search of the lady for whom he had asked, not, however, without taking a sidelong glance at his handsome face before she disappeared.

The apartment was a long dining-room, extending from the front to the back of the house, furnished amply, yet with a certain richness, the articles being all of old oak, carved elaborately, which lent a somber, somewhat stately effect. It was obviously, however, a room in a semifashionable boarding-house.

In a few minutes a lady opened the door, and entered with the joyous eagerness of a girl.

A graceful, dignified woman, in reality seventeen years older than Captain Desfrayne, but who looked hardly five years his senior, of the purest type of English matronly beauty. She seemed like one of Reynolds’ or Gainsborough’s most exquisite portraits warmed into life, just alighted from its canvas. The soft, blond hair, the clear, roselike complexion, the large, half-melting violet eyes, the smiling mouth, with its dimples playing at hide-and-seek, the perfectly chiseled nose, the dainty, rounded chin, the patrician figure, so classically molded that it drew away attention from the fact that every little detail of the apparently little-studied yet careful toilet was finished to the most refined nicety—these hastily noted points[Pg 12] could scarce give any conception of the almost dazzling loveliness of Paul Desfrayne’s widowed mother.

She entered with a light, quick step, and being met almost as she crossed the threshold by her visitor, she raised her white hands, sparkling with rings, and drew down his head with an ineffably tender and loving touch.

“My boy—my own Paul,” she half-cooed, kissing his forehead. “This is, indeed, an unexpected pleasure. I did not even know that you were in London.”

For a moment the young man seemed about to return his mother’s caress; but he did not do so.

She crossed to the window, and placing a second chair, as she seated herself, desired Paul to take it.

There was a positive pleasure in observing the movements of this perfectly graceful woman. She seemed the embodiment of a soft, sweet strain of music; every gesture, every fold of her draperies was at once so natural, yet so absolutely harmonious, that it was impossible to suggest an alteration for the better.

“I supposed you to be settled for a time in Paris,” Mrs. Desfrayne said, as her son did not appear inclined to take the lead in the impending dialogue, but accepted his chair in almost moody silence.

“I should have written to you, mother; but I thought I should most probably arrive as soon, or perhaps even precede my letter,” replied Captain Desfrayne.

“You look anxious and a little worried. Has unpleasant business brought you back? You have not obtained the appointment to the French embassy for which you were looking?”

“No. I am anxious, undoubtedly; but I suppose I ought not to say I am worried, though I find myself placed in a most remarkable, and—what shall I say?—delicate position. Yesterday I received a letter, and I came at once to consult you, with the hope that you might be able to give me some good advice. I fear I have called at rather an unreasonable hour?”

A tenderly reproachful glance seemed to assure him that no hour could be unreasonable that brought his ever-welcome presence.

[Pg 13]

“I will advise you to the best of my ability, my dear,” Mrs. Desfrayne smilingly said. “What has happened?”

Paul Desfrayne drew a letter from the pocket of the light coat which he had thrown over his evening dress, and looked at it for a moment or two in silence, as if at a loss how to introduce its evidently embarrassing contents.

His mother watched him with undisguised anxiety, her brilliant eyes half-veiled by the blue-veined lids.

“This letter,” Paul at length said, “is from a legal firm. It refers to a person whom I had some difficulty in recalling to mind, and places me in a most embarrassing position toward another person whom I have never seen.”

“A situation certainly indicating a promise of some perplexity,” Mrs. Desfrayne half-laughingly remarked.

“Some years ago,” Paul continued, “there lived an old man—he was an iron-dealer originally, or something of that sort—a person in a very humble rank of life; but somehow he contrived to make an enormous fortune. He has, in fact, left the sum of nearly three hundred thousand pounds.”

“To you?” demanded Mrs. Desfrayne, in a thrilling tone, not as if she believed such to be the case; for her son’s accent scarcely warranted such an assumption; but as if the wish was father to the thought.

Paul shook his head.

“Not to me—to some young girl he took an interest in, as far as I can understand. I happened to render him a slight service—I hardly remembered it now—some insignificant piece of civility or kindness. It seems he entertained a great respect for me, and attributed the rise of his wealth to me. This young girl—I don’t know whether she was related to him or not—has been left the sole, or nearly the sole, inheritor of his money, and I——”

“And you, Paul?”

“Have been nominated her trustee and sole executor by his will. I believe he has bequeathed me some few thousands, as a remuneration for my trouble.”

The slight tinge of pinky color on the cheeks of the[Pg 14] beautiful Mrs. Desfrayne deepened visibly, although she sat with her back to the window.

“How old is the young lady?” she asked, in a subdued tone.

“Eighteen or nineteen.”

“Is she—has she any father or mother?”

“Both are dead. She is, I understand, alone in the world.”

“Have you seen her?”

“No.”

“Do you know what she is like?”

“I am as ignorant of everything concerning her, personally, as you are yourself, mother.”

“Is she pretty?”

Paul Desfrayne’s face hardened almost to sternness and his eyes drooped.

“I have already told you, mother mine, that I know nothing whatever about her. If you will take the trouble to glance over this letter, you will learn as much as I know myself. I have nothing more to tell you than what is written therein.”

The dainty fingers trembled slightly as they were quickly stretched forth to receive the missive, which Paul took from its legal-looking envelope.

Mrs. Desfrayne ran rapidly over the contents, and then read it through more slowly a second time.

It purported to be from Messrs. Salmon, Joyner & Joyner, the eminent firm of solicitors in Alderman’s Lane, and requested Captain Desfrayne to favor them with a call at his earliest convenience, as they wished to go over the will of Mr. Vere Gardiner, iron-founder, lately deceased, who had appointed him—Captain Desfrayne—sole trustee to the chief legatee, an orphan girl of nineteen, sole executor to the estate, which was valued at about two hundred and sixty thousand pounds, and legatee to the amount of ten thousand pounds. The letter added that Mr. Vere Gardiner had expressed a profound respect for Captain Desfrayne, and had several times declared that he owed his uprise in life to a special act of kindness received from him.

“How very extraordinary!” Mrs. Desfrayne softly exclaimed,[Pg 15] at length. “He scarcely knew you, yet trusts this young girl and her large fortune to your sole charge. Flattering, but, as you say, embarrassing. Two hundred and sixty thousand pounds!” she murmured. “A girl of nineteen. If she is a beauty”—she slightly shrugged her dimpled shoulders—“your position will be an onerous one, indeed.”

“They might as well have asked me to play keeper to a white elephant,” the young man said, with some acerbity. “I will have nothing to do with it.”

“Do not be too hasty. Probably this person had good reason for what he has done. Besides, you would be foolish to refuse so handsome a present as you are promised; for we cannot conceal from ourselves that ten thousand pounds would be a very acceptable gift.”

“If a free one, yes; if burdened with unpleasant conditions, why, there might be difference of opinion. I had almost made up my mind to decline at once and for all; but I thought it would be more prudent to consult you first.”

“My dear Paul, I feel—I will not say flattered, but I thank you very much for your kind estimation of my judgment. All I can say is: Go and see what these lawyers have to say. Then, if they do not succeed in inducing you to receive the trust, see the girl, and judge for yourself what would be best. Perhaps she has no friend but you, and she might run the risk of losing her fortune. Perhaps she is sorely in need of some protector—perhaps even of money. Where does she live?”

“As I told you before,” Captain Desfrayne replied, with more asperity than seemed at all necessary under the circumstances, “I did not know even of her existence before receiving that letter, and I now know not one solitary fact more than you do. I know nothing of the girl, or of her money. I do not wish to know; I take no interest, and I don’t want to take any interest now, or in the future.”

“But it is foolish to refuse to perform a duty when you are so entirely ignorant of the reasons why this money has been thrown into your keeping,” urged Mrs. Desfrayne gently.

[Pg 16]

“If I refuse, I suppose the Court of Chancery will find somebody more capable, and certainly may easily find some one more willing than myself,” Captain Desfrayne said, almost irritably.

“If it had been a boy, instead of a girl, would you have been so reluctant?” asked Mrs. Desfrayne, smiling mischievously.

“That has nothing to do with it. I have to deal with the matter as it now exists, not as it might have been.”

Mrs. Desfrayne glanced at her son from beneath the long, silken lashes that half-concealed her great blue eyes. It seemed so strange to hear that musical voice, which for nine-and-twenty or thirty years had been as soft and sweet to her ears, as if incapable of one jangled note, fall into that odd, irritable discordance.

Paul was out of sorts and out of humor, she could see. Was he telling her all the truth?

Never, in all those years of his life, most of which had passed under her own vision, had he uttered, looked, or even seemed to harbor one thought that he was not ready and willing for his mother to take cognizance of. Why, then, this possible reticence, blowing across their lifelong confidence like the bitter northeast wind ruffling over clear water, turning its surface into a fragile veil of ice?

The young man was out of humor, for his meeting with the fellow whom he had just encountered almost on the threshold of the house had brought up many recollections he would fain have banished—memories of a time he would gladly have erased from the pages of his life—a time whereof his mother knew nothing.

Mrs. Desfrayne, however, shot very wide of the mark when she ascribed his alteration of look and manner to some foreknowledge of the girl in question. He spoke nothing but the truth in saying that he had never as much as heard of her before receiving the letter that lay between his mother’s fingers.

With the electric sympathy of strong mutual affection, Paul Desfrayne quickly perceived the ill effect his coldness had upon his mother; and with an effort he cleared[Pg 17] his countenance, and assumed a shadow of his formerly smiling aspect. He looked down, and appeared to consider. Then, raising his eyes to those of his mother, he said, with an air of resignation:

“I suppose it would be best to see the lawyers, and hear what they have to say. It is a most intolerable bore. I don’t know what I have done to merit being visited for my sins in this fashion.”

“You don’t remember what you happened to do for this eccentrically disposed old man?”

Paul Desfrayne shrugged his shoulders.

“A remarkably simple matter, when all is said and done. I was traveling once with him, as well as I can remember, and he began talking to me about some wonderful invention he had just brought to perfection. He was in what I supposed to be rather cramped circumstances, though not an absolutely poor man, for he was traveling first-class. I should not have thought about him at all, only, with the enthusiasm of an inventor, he persisted in bothering me about this thing.

“I thought at the time it was deserving of notice; and when he alighted, I happened to almost tumble into the arms of the very man who had it in his power to get the affair into use and practise. More to get rid of him than for any more worthy motive, I introduced the two to each other. It was something this old Vere Gardiner had invented, for some kind of machinery, which, if adopted by the government, would save—I really forget how much. I recollect asking this friend, some time after, if he had done anything about it, and he told me it would probably make the fortune of half a dozen people. He seemed delighted with the old man and his invention.

“This must be the service he made so much of. It was a service costing me just five or six sentences. I did not even stop to see what Percival, this friend, thought of old Gardiner, or what he thought of Percival; but left them talking together in the waiting-room, for I was in a desperate hurry to reach you, mother. I never anticipated hearing of the affair again.”

[Pg 18]

There was a brief silence.

“This man, it is to be presumed, was of humble birth,” said Mrs. Desfrayne. “It will be too dreadful if, with the irony of blind fate, this girl proves unpresentable. In that case—at nineteen—it will be too late to mend her manners, or her education. Perhaps she has some frightfully appalling cognomen, which will render it a martyrdom to present her in society. If she is anything of a hobgoblin, you may with justice talk of a white elephant.”

“I suppose there is no clause in the criminal code whereby I may be compelled to accept the trust if I do not elect voluntarily to undertake it?” Captain Desfrayne asked, with a slight smile at his mother’s fastidious alarm. “And if she is nineteen now, I suppose my responsibility would cease in two years?”

“Perhaps. Some crotchety old men make very singular wills. I wonder how it happened that he had no business friend in whom he could confide?—why he must choose a stranger, and entrust to that stranger such a large sum? I wish I knew what the girl’s name is, and what she is like, and what possible position she may occupy? For if you receive the trust, I presume I shall have the felicity of playing the part of chaperon.”

“It is perfectly useless discussing the matter until we know something more certain,” Captain Desfrayne said, his irritation again displaying itself unaccountably.

“One cannot help surmising, my dearest Paul. Perhaps the girl is a nursemaid, or a milliner’s apprentice, and misuses her aspirates, and is a budding Malaprop,” Mrs. Desfrayne persisted. “However, we shall see. Go with me this evening to the opera, if you have nothing better to do. Lady Quaintree has lent me her box.”

As she was folding her opera-cloak about her youthful-looking person the good lady said to herself:

“There is some mystery here; but of what kind? Paul is not quite his own frank self. What has happened? He has kept something from me. I could not help fancying something occurred during his absence in Venice three years ago. I wonder if he knows more about this girl,[Pg 19] the fortunate legatee of the eccentric old iron-founder, than he chooses to acknowledge? But he must have some most powerful reason to induce him to hide anything from me; and he said twice most distinctly that he had never seen her and did not know her name. I do not believe Paul could be guilty of deceit.”

[Pg 20]

CAPTAIN DESFRAYNE’S PERPLEXITY.

The midday sun made an abortive effort to struggle down between the tall rows of houses on either side of busy, hurrying Alderman’s Lane, glinting here and glancing there, showering royal largesse.

The big building devoted to the offices of Messrs. Salmon, Joyner & Joyner was lying completely bathed in the golden radiance; for it occupied the corner, where the opening of a street running transverse allowed the glorious beams to descend unimpeded.

A great barracklike edifice, more like a bank than a lawyer’s city abode. A wide flight of steps led up to a handsome swing door, on which a brightly burnished plate blazoned forth the name of the firm. This opened upon an oblong hall, in which were posted two doleful-looking boys, each immured in a kind of walled-off cell; a spacious staircase ran from this hall to a succession of small, cell-like apartments, all furnished in as frugal a manner as was compatible with use; a long table, covered with piles of papers of various descriptions; three or four hard chairs; a bookcase crammed with tall books bound in vellum, and morose-looking tin deed-boxes labeled with names.

In one of these dim, uninviting cells sat a gentleman, apparently quite at ease, his employment at the moment the scene draws back and reveals him to view being the leisurely perusal of the Times; a man of perhaps the same age as Captain Desfrayne—a pleasant, grave-looking gentleman, with kindly dark eyes, a carefully trimmed dark-brown beard, a pale complexion, and a symmetrical figure.

One of the melancholy walled-in youths suddenly appeared to disturb the half-dreamy studies of this serene personage.

Throwing open the door, he announced:

“Captain Desfrayne.”

[Pg 21]

The captain walked in, and the door was shut.

The occupant of the apartment had risen as the youth ushered in the visitor, and advanced the few steps the limited space permitted, smiling with a peculiarly winning expression.

“Mr. Amberley?” questioned Captain Desfrayne.

“I have called,” he went on, as the owner of that name bowed assentingly, “in obedience to a letter received by me from Messrs. Salmon, Joyner & Joyner.”

He threw upon the table the letter he had shown to his mother, and then seated himself, as Mr. Amberley signed for him to do.

Mr. Amberley, in spite of the latent smile in his dark eyes, seemed to be a man inclined to let other people save him the trouble of talking if they felt so disposed. He took up the letter, extracted it from its envelope, and unfolded it.

“Mr. Salmon and Mr. Willis Joyner wished to meet you, together with myself,” he remarked, “but were obliged to attend another appointment. In the meantime, before you can see them, I shall be happy to afford you all necessary explanations.”

“Which I very much need, for I am unpleasantly mystified. In the first place, I am at a loss to comprehend why this client of yours should have selected me as the person to whom he chose to confide so vast a trust,” Captain Desfrayne replied, in a tone almost bordering on ill humor.

“I am quite aware of the fact that you were not a personal friend of Mr. Vere Gardiner,” said the lawyer. “He trusted scarcely any one. I believe he entertained a painfully low estimate of the goodness or honesty of the majority of people. Of his particular object in giving this property into your care, I am unable to enlighten you. I know that he took a great interest in you; and as he frequently sojourned in the places where you happened to be staying, I have no doubt he had every opportunity of becoming acquainted with as much as he wished to learn of—of—— In fact, I have no grounds beyond such observations as may have been made before me for judging that he did take an interest in you. If[Pg 22] you are surprised by the circumstance of his appointing you to such a post, I think you will probably be infinitely more so when you hear the contents of the will.”

He rose, and took from an iron safe a piece of folded parchment, which he spread open before him on his desk.

Captain Desfrayne said nothing, but eyed the portentous document with an odd glance.

“The history of this will is perhaps a curious one,” Mr. Frank Amberley resumed. “Mr. Vere Gardiner was, when a young man, very deeply attached to a young person in his own rank of life, whom he wished to marry. She, however, preferred another, and refused the offers of Mr. Gardiner. He never married. In a few years she was left a widow. He again renewed his offer, and was again refused. He was very urgent; and, to avoid him, she changed her residence several times. The consequence was, he lost sight of her. He became a wealthy man, chiefly, he always declared, through your instrumentality. After this he found this person—when he had, so to speak, become a man of fortune—again renewed his offer of marriage, and was again refused as firmly as before. She had one child, a daughter.”

The lawyer turned to look for some papers, which he did not succeed in finding, and, having made a search, turned back again.

Captain Desfrayne made no remark whatever.

“He offered to do anything, or to help this Mrs. Turquand in any way she would allow him: to put the child to school, or—— In fact, his offers were most generous. But she persistently shunned him, and refused to listen to anything he had to say. He lost sight of her for some years before his death, and did not even know whether she was living or dead.

“It was accidentally through—through me,” the lawyer continued, speaking with a visible effort, as if somewhat overmastered by an emotion inexplicable under the circumstances—“it was through me that he learned of the death of the mother and the whereabouts of the daughter.”

“The latter being, I presume, the young lady whom he[Pg 23] has been kind enough to commit to my care?” Captain Desfrayne asked.

Mr. Amberley twirled an ivory paper-cutter about for a moment or two before replying.

“Precisely so. I happen to be acquainted with—with the young lady; and he one day mentioned her name, and said how anxious he was to find her. I volunteered to introduce her to him; but he was then ill, and the interview was deferred. He went to Nice, the place where Mrs. Turquand had died, and drew his last breath in the very house where she had been staying. In accordance with his dying wishes, he was buried close by the spot where she was laid. The will was drawn up a few weeks before he quitted England.”

“I certainly wish he had selected any one rather than myself for this onerous trust,” Captain Desfrayne said, with some irritation. “What is the young lady’s name? Miss Turquand?”

Mr. Amberley hesitated, took up the will, and laid it down again; then took it up, and placed it before Captain Desfrayne.

“If you will read that, you will learn all you require to know,” he replied, without looking up.

He had been perfectly right in remarking that, if Captain Desfrayne had felt surprised before, he would be doubly astonished when he came to read Mr. Vere Gardiner’s will.

Captain Desfrayne was fairly astounded, and could scarcely believe that he read aright. The sum of two hundred and sixty thousand pounds was left, divided equally into two portions, but burdened largely with restrictions.

One hundred and thirty thousand pounds was bequeathed to Lois Turquand, a minor, spinster. Until she reached the age of twenty-one, however, she was to receive only the annual income of two thousand pounds.

The second half—one hundred and thirty thousand pounds—was left to Paul Desfrayne, Captain in his majesty’s One Hundred and Tenth Regiment, he being appointed also sole trustee, in the event of his being willing to marry the aforesaid Lois Turquand when she reached[Pg 24] the age of twenty-one. In case the aforesaid Lois Turquand refused to marry him, he was to receive fifty thousand pounds; if he refused to marry her, he was to have ten thousand pounds. If they married, the sum of two hundred and sixty thousand pounds was to be theirs; if not, the money forfeited by the non-compliance with this matrimonial scheme was to be distributed in equal portions among certain London hospitals, named one by one.

Three thousand pounds was left to be divided among the managers of departments and persons in positions of trust in the employ of the firm; one thousand among the clerks in the office, and five hundred among the domestics in his service at the time of his death.

In the event of the demise of Lois Turquand before attaining the age of twenty-one, Paul Desfrayne was to receive a clear sum of one hundred and thirty thousand pounds; the other moiety to be divided among the London hospitals named.

Mr. Amberley was closely regarding Captain Desfrayne as the latter read this will—to him so singular—once, twice. When Captain Desfrayne at length raised his head, however, Mr. Amberley’s glance was averted, and he was gazing calmly through the murky window at the radiant blue summer sky.

For some minutes Captain Desfrayne was unable to speak.

“It is the will of a lunatic!” he at length impatiently exclaimed.

“Of a man as fully in possession of his senses as you or I,” calmly replied Mr. Amberley. “You do not seem to relish the manner in which he has claimed your services.”

“I don’t know what to think—what to say. I wish he had selected any one rather than myself, which you will say is ingratitude, seeing how magnificently he has offered to reward me. When shall I be obliged to go through an interview with the young lady?”

“Whenever you please—this afternoon, if convenient to you.”

[Pg 25]

Captain Desfrayne looked at the lawyer, as if startled. It almost seemed as if he turned pale.

“When, I suppose, I am to enjoy the privilege of breaking the news?” he demanded, with a little gasp.

“You speak as if the prospect were anything but pleasing. If you object to the task, it will, perhaps, be all the better to get it done at once.”

“Where does she live?”

“She is staying with Lady Quaintree, in Lowndes Square.”

Paul Desfrayne recollected, with a queer feeling of surprise, that his mother had said the previous evening that Lady Quaintree had lent her the opera-box which she had used. Could it be possible that his mother already knew this girl?

“Lady Quaintree!” he repeated mechanically.

“Certainly. Miss Turquand has been living there for two or three years; she is her ladyship’s companion. If you have no other engagement of pressing importance, I fancy the most easy and agreeable way would be to call at the house this evening, about eight o’clock. Lady Quaintree is to have some sort of reception to-night, and, as I am almost one of the household, we could see her before the people begin to arrive.”

Paul Desfrayne gave way to fate. There was no help for it, so he was obliged to agree to this arrangement, or choose to think himself obliged, which was worse.

Frank Amberly thought that not many men would have received with such obvious repugnance the position of sole trustee to a beautiful girl of eighteen, who had just become entitled to a splendid fortune, especially when there were such provisions in his own favor.

“It is thus he receives what I would have given—what would I not have given?—to have obtained the trust,” he said mentally, with a keen pang of jealous envy.

It was a strange freak of Dame Fortune—who yet must surely be a spiteful old maid—to bring these two men, of all others, into such communication.

Paul Desfrayne’s thoughts were in a kind of whirl, an entanglement which was anything but conducive to clear deliberation or calm reflection. They eddied and[Pg 26] surged with deadly fury round one great rock that reared its cruel black crest before him, standing there in the midst of his life, impassive, coldly menacing.

Hitherto, with the exception of one fatal occasion, he had always consulted his mother on all matters of difficulty or perplexity. But now he must carefully conceal his real thoughts from that still beloved counselor. It was useless to go to her, as of yore, for advice as to the best course to take: he dared not tell her this miserable secret which bound him in a viselike grip. His mother would at once, he knew—unconscious that any link in the chain was concealed from her—say he must be mad not to accept, without hesitation, this trust. She would certainly urge him, for the sake of this unknown girl herself. He must decide now: it would, perhaps, only make matters worse if he delayed, or asked time for consideration.

Besides, if he refused, what rational reason could he assign to any one of those concerned for declining the trust?

No; he must agree to whatever was set before him now, although by so doing he would almost with his own hands sow what might prove to be the most bitter harvest in the future.

He was within a maze, wherein he did not at present discern the slightest clue to guide him to the outlet of escape. It was impossible to explain his position to any one, yet he felt that it was next to pitiful cowardice to march under false colors.

One thing was clear: if he could not explain his reasons for declining to accept what, while somewhat eccentric, was a fair and apparently tempting offer, he must be ready to take the place assigned to him. Not only was this self-evident, but also that no matter what time he must ask for reflection, his position could not be altered, and he could give no plausible excuse of any kind to his mother for rejecting such princely favors.

“This young lady is not—is not, then, acquainted with the contents of this will?” he asked, raising his head, and speaking somewhat wearily.

[Pg 27]

“Not as yet. We thought it best to wait until you could yourself make the communication.”

He might as well face the girl now, and have it over, as leave it to a month, six months, a year hence. He was a soldier, yet a coward and afraid; but he shut his eyes, as he might if ordered to fire a train, and resolved to go through with the task, which, to any other one—taken at random from ten thousand men—must have been a pleasant duty.

The lawyer regarded him with surprise, but could not, of course, make any remark. His wide experience had never supplied him with a parallel case to this: of a man receiving such rare and costly gifts from fortune with clouded brow and half-averted eye. The hopes, however, which had well-nigh died within his breast, of winning the one bright jewel he coveted, revived, if feebly.

“There is something strangely amiss,” he thought; “but she will be doubly, trebly shielded from the slightest risk of harm.”

Captain Desfrayne—his troubled gaze still on the open parchment, which he regarded as if it were his death-warrant—absolutely started when Mr. Amberley addressed him, after a short silence, inviting him to partake of some wine, which magically appeared from a dim, dusty-looking nook.

After a little desultory conversation, having arranged the hour of meeting and other necessary details, Frank Amberley observed, an odd smile lurking at the corners of his handsome mouth:

“This is not the first time we have met, though you have apparently forgotten me.”

The captain looked at him.

“I really do not remember you,” he said, with a puzzled expression.

“You do not remember a certain moonlight night in Turin, when you shot a bandit dead, as his dagger was within five or six inches of an Englishman’s throat? Nor an excursion which took place some weeks previously, when you met the same compatriot in a diligence—myself, in fact? We wrote down one another’s names, and were going to swear an eternal friendship, when you were[Pg 28] abruptly obliged to quit the city, in consequence of some business call, or regimental duties.”

“The circumstances have by no means escaped my memory,” answered Captain Desfrayne, in an indefinable tone; “though I should have scarcely recognized you. Since then you have a little altered.”

Frank Amberley, laughingly, stroked the silken beard, which had certainly greatly changed his aspect. But the coldness of the formerly open, frank-hearted man, whom he had so liked three or four years ago, struck him with deepened suspicion that something was amiss.

“I am glad to have met you,” he said. “I should be very pleased if you could dine with me this evening at the ‘London.’ My people are going out this evening, so I am compelled to make shift as I best can, and I don’t relish dining alone at home.”

A brief hesitation was ended by Paul Desfrayne accepting this free-and-easy invitation.

The two young men then shook hands and parted, with the agreement to meet again for a six-o’clock dinner.

Truly, times, places, and things had altered since those days at Turin, the recollection of which seemed to bring scant pleasure to Paul Desfrayne’s weary heart.

“Some fatal secret has become ingrained with that man’s life,” said the young lawyer, as he closed the door upon his visitor. “Great heavens! that Lois Turquand should spurn my love, and be thrown, perhaps, into the unwilling arms of a man like this, with such a hunted, half-guilty look in his eyes! It shall not be—it cannot be! Fate could not be so cruel!”

[Pg 29]

LOIS TURQUAND’S EMBARRASSMENT.

The sun, that was shut out by towering walls from the busy city, like some intrusive idler, was lying, half-slumbrously, like some magnificent Eastern slave arrayed in jewels and gold, among the brilliant-hued and many-scented flowers heaped under the striped Venetian blinds stretched over the balconies of a mansion in Lowndes Square.

An occasional soft breeze lifted the curtains lowered over the windows, granting a transient vision of apartments replete with luxury, glowing under the influence of an exquisitely delicate taste.

Within the principal drawing-room sat a stately matron, with silver-white hair, attired in full evening costume, apparently awaiting the arrival of expected guests.

Lady Quaintree was handsome, even at sixty, with a soft, clear skin, and a complexion girlishly brilliant; a figure full, without being dangerously stout; a most wondrously dainty hand, on which sparkled clusters of rings that might have formed a king’s ransom. Her ladyship had been a beauty in her youth—not a spoiled, ill-humored beauty, but one kind and indulgent, much flattered and loved, taking adoration as her due, as a queen accepts all the rights and privileges of her position.

A woman made up of mild virtues—good, though not religious; kind and pleasant, though not benevolent, abhorring the poor, and the sick, and the unfortunate—the very name of trouble was disagreeable to her. This world would have been a sunny, rose-tinted Arcadia could she have had her way; it should have been always summer.

She went regularly to church on Sunday morning with great decorum, turning over the pages of her beautiful ivory-covered church service at the proper time, and always put sovereigns on the plate with much liberality when there was a collection. She gave directions to her housekeeper in the country to deal out coats, and blankets,[Pg 30] and all that sort of thing, to deserving applicants. If flower-girls, or wretched-looking beggars, crowded round her carriage when she went out shopping, they not unfrequently received sixpences as a bribe to take themselves and their miseries out of sight.

So that, altogether, her ladyship felt she had a reason to rely on being defended from all adversities which might happen to the body, and all evil thoughts which might assault and hurt the soul.

Lady Quaintree was nearly asleep when a liveried servant drew aside the velvet portière, and announced:

“Captain Desfrayne and Mr. Amberley!”

Paul Desfrayne’s glance swept the suite of apartments, as if in search of the girl who unconsciously held the threads of his destiny in her hands; but, to his relief, she was not to be seen.

He allowed himself to be led up to the mistress of the house, and went through the ceremony of introduction like one in a dream. Lady Quaintree spoke to him, and made some smiling remarks; but he was unable to do more than reply intelligibly in monosyllables. The first words that broke upon his half-dazed senses with anything like clearness were uttered by Frank Amberley.

“Not so much, my dear aunt, to pay our respects to you as to communicate a most important matter of business to—to Miss Turquand. I suppose we ought to have come at a proper hour in the business part of the day, but it was my idea to, if possible, take off the—in fact, I imagined it might be the most pleasant way of introducing Captain Desfrayne to bring him here this evening.”

Lady Quaintree had opened her eyes at the commencement of this speech.

“A most important matter of business concerning Miss Turquand?” she said. “What can it possibly be?”

“She certainly ought to be the first to hear it,” replied Frank Amberley; “though, as her nearest friend, my dear aunt, you ought to learn the facts as soon as herself.”

“You have a sufficiently mysterious air, Frank. I feel eager to hear these wonderful tidings.”

[Pg 31]

Her ladyship felt a little piqued that her nephew did not offer at once to give her at least some hint of what the important matter of business might be about.

A sudden thought seemed to strike her, and she rang a tiny, silver hand-bell with some sharpness, while an expression of anxiety crossed her face. As she did so, a figure, so ethereal that it seemed like an emanation of fancy, floated unexpectedly from the entrance to the farthest room, and came down the length of the two salons beyond that in which the little group was stationed.

For a moment it seemed as if this fairylike vision had appeared in response to the musical tingling of the bell.

A girl of eighteen or nineteen, dressed in the familiar costume of Undine. A figure, tall, full of a royal dignity and repose, like that of a statue of Diana. A face surrounded by a radiant glory of sun-bright hair, recalling those pure saints and martyrs which glow serenely mild from the dim walls of old Italian or Spanish cathedrals. Many faults might be found with that face, yet it was one that gained in attraction at every glance.

The young girl advanced so rapidly down the rooms that she was standing within a few feet of the two gentlemen before she could plan a swift retreat.

A vivid, painful blush overspread her face, and she stood as if either transformed into some beautiful sculptured image, or absolutely unable to decide which would be the worst of evils—to remain or to fly.

She turned the full luster of her translucent eyes upon Captain Desfrayne, as some lovely wild creature of the forest might gaze dismayed at the sight of a hunter, and then recoiled.

Lady Quaintree rose, and quickly moved a few steps, as if to intercept her, and said:

“My dear, don’t run away. Frank Amberley knows all about the tableau for which you are obliged to prepare. I thought you would have come down before to let me see how the dress suited; but I suppose that abominable Lagrange has been late, as usual. My dear Lois, I am dying with curiosity. These gentlemen—Captain Desfrayne and Mr. Frank Amberley—have come to tell you some wonderful piece of business, and I want to[Pg 32] know what it is as soon as possible. Pray stop. You will only lose time if you go to change your dress.”

“I beseech you, madam, let me go,” pleaded Lois Turquand, troubled by her unforeseen, embarrassing situation—strangely troubled by the steadfast gaze which Paul Desfrayne, in spite of himself, fixed upon her.

“Nonsense! You must hear what they have to say. I feel puzzled, and anxious to know.”

Lois vainly tried to avoid that singular, inexplicable look, which seemed to master her. Had she not been so suddenly taken at a disadvantage, she would have repelled it with displeasure. As it was, she had a curious sense of being mesmerized. She ceased to urge her entreaty for permission to depart, and stood motionless, though her color fluctuated every instant.

[Pg 33]

LOIS TURQUAND’S ALTERED FORTUNE.

Frank Amberley looked at Captain Desfrayne, who drew back several steps—for neither had seated himself, although Lady Quaintree had signed to them to do so.

It was evident that Captain Desfrayne would not take the initiative, so Frank Amberley was obliged to explain—more to Lady Quaintree than to her protégée—that Miss Turquand had been left heiress to a fortune of one hundred and thirty thousand pounds.

“To just double that sum in reality; but there are certain conditions attached to the larger amount, which must be fulfilled, or the second moiety is forfeited,” Mr. Amberley continued, looking down, his voice not quite so steady as it had been when he began. “I have had a copy of the will prepared, which Miss Turquand might like to read before seeing the original.”

He had a folded paper, tied with red tape, in his hand, which he placed on a table close by Lois. As he did so, his eyes rested for a moment upon her with a strange, mingled expression of passionate love and profound despair, at once pathetic and painful.

The young girl still stood immovable, as if in a dream. Her luminous eyes turned upon the document; but she did not attempt to touch it, or show in any way that she really comprehended what had been said, except by that one swift glance of her eyes upon the paper.

“This gentleman—Captain Desfrayne—has been appointed by Mr. Gardiner, Miss Turquand’s trustee.”

The brilliant eyes were turned for an instant to the countenance of Captain Desfrayne, and then withdrawn; while still deeper crimson tides flooded over the lovely face.

“How very extraordinary!” said Lady Quaintree, as if scarcely able to understand. “How very singular!” she repeated emphatically.

“I am truly glad,” she cried, pulling the cloudy figure[Pg 34] toward her, and kissing the fair young face. “So my little girl is a wealthy heiress. What will you do with all your money? Go and live in ease, and give fêtes and garden-parties, and have revels at Christmas, and amateur theatricals, and knights and ladies gay, or devote yourself to schools and almshouses, as a favorite hobby? Come, a silver sixpence for your thoughts.”

Lois, standing perfectly still, leaning against the table, with her hand resting on the carved back of her patroness’ chair, glanced at her ladyship, at the lawyer, and at Captain Desfrayne. Then the soft, sweet eyes drooped. She made no answer. It was impossible to tell from her face what her feelings might be.

Lady Quaintree was greatly disappointed by this cool reception of the marvelous news, which had thrown herself into a state of pleasurable excitement. She turned to her nephew with eager curiosity.

“Can you tell me a few morsels of the contents of this wonderful will?” she asked. “Who made the will? Who has left all this money to my dear girl? What was he? and why has he been so generous?”

Lady Quaintree had been quite fond of her companion; but this sudden access of affection was due to the delightful intelligence brought by the lawyer.

“The will would explain more clearly than I could do all particulars,” Frank Amberley replied.

He felt it was absolutely impossible at that moment to enter into any elucidation whatever, or even to give an outline of the conditions of the will.

Lois extended the document toward Lady Quaintree.

“Is it very long?” her ladyship demanded, glancing at Frank Amberley.

“It may take you five minutes to read it,” he answered.

She unfolded the paper, and ran her eye rapidly over the contents. Not one of the others uttered a word—not one ventured to look up, but remained as if carved out of stone.

Lois found it well-nigh impossible to analyze her sensations; but certainly the predominant one was that she must be in a dream. She had every reason to be happy with her protectress, who was as kind as if the near ties[Pg 35] of relationship bound them together; but it would probably be quite useless to search the world for the girl of eighteen who could hear unmoved that she had suddenly become the owner of a large fortune, especially if that girl happened to be in a dependent position, and to move constantly amid persons with whom money, rank, and fashion were paramount objects of devotion.

She was the daughter of a court embroideress, who had earned about four hundred a year by her labors and those of her assistants; but Mrs. Turquand had never been able—or thought she had not been—to lay by any portion of her income as a provision for her child. Lady Quaintree had always liked Lois as a child, and at the death of her mother, three years since, had taken her to be useful companion and agreeable company for herself.

That Lois had any expectations from any quarter whatever, nobody ever for a moment supposed. Everybody of Lady Quaintree’s acquaintance knew and liked the young girl, who was so pretty, so obliging, so sweet-tempered. That she should now be suddenly transformed into the inheritress of great wealth was something like an incident in a fairy-tale.

Mr. Amberley’s reflections were easily defined. He had for months past loved this young girl, though he had never yet had sufficient courage to declare as much, for she seemed totally unconscious of his preference, and, while certainly not distant nor icy with him, never gave him the slightest reason to suppose that she ever as much as remembered him when he was absent. He had, however, the satisfaction of feeling sure that she cared for no one else. Never even remotely had he hinted to Lady Quaintree his secret, being well aware she would discountenance his suit, for many reasons.

It was with the utmost bitterness of spirit that he had seen the girl apparently removed from the possibility of his being able to pay court to her; and at the same time not only delivered into the sole charge of a probable rival, but bound by the most stringent injunctions to marry a young, handsome, and in every way attractive, man—a man whom he judged, in his own distrustful humility,[Pg 36] much more likely to seize the fancy of a young beauty than he himself was.

Paul Desfrayne’s thoughts were utterly confused. Since entering the room, he had scarcely spoken three sentences, and he heartily wished himself anywhere rather than in this softly illumined suite of rooms, facing this beautiful girl with the angelic face, whom he had been commanded and largely bribed to fall in love with and make his wife.

He dreaded the moment when Lady Quaintree should drop her gold-rimmed eye-glass, and the silence should be broken. At the same time, the thought of his mother never left him. What would she say when she learnt the contents of this terrible will? Only too well he foresaw the scenes he should be obliged to go through. As for this girl herself, lovely as some poet’s vision, he resolved to see as little of her as might be compatible with the fulfilment of his legal duties and responsibilities toward her. What a pitiful coward he felt himself! Why could he not tell the truth, and save so much possible future suffering?

Lady Quaintree read through the closely written document, and then, folding it up, stared at each of the three persons before her, with an almost comic expression of amazement upon her fair, unwrinkled countenance.

“Captain Desfrayne,” she said, smiling as she held out her hand, “I trust you will be pleased to remain with us this evening as long as your inclinations or other engagements permit. I expect some very pleasant friends—some really distinguished persons, with whom you may either already be well acquainted, or whom you might not object to meet.”

There was such a stately yet gracious dignity in her manner that Captain Desfrayne caught the infection, and bowed over the delicate white hand with almost old-fashioned chivalric courtesy.

“You will pardon my leaving you two gentlemen alone for a few minutes,” she added. “Lois, my love, I will go with you to your room.”

Lady Quaintree quitted the salon, followed by the beautiful figure, clad in its cloudy robes of ethereal white.

[Pg 37]

“Let us go at once to your apartment, my child,” she said, leading the way.

Her eyes were bright with eager excitement, for she was surprised and pleased by the totally unexpected change in her young companion’s fortunes; and she loved the girl so much that she was rejoiced to see her rise from her inferior station to one of wealth—to see so fair and sunny a prospect opening before her.

She glided up the stairs with a step so alert that forty years seemed lifted from her age; and in a minute they were within the precincts of the pretty room which was the domain of Lois Turquand.

“My love,” Lady Quaintree said, closing the door with a careful hand, “I am so pleased I can hardly tell you how much. You, no doubt, wish to know the contents of this wondrous paper? My dear, it is as interesting as a fairy-tale. You are a good girl, and deserve all the good fortune Heaven may please to send you.”

She kissed the young girl’s forehead very kindly. Lois returned the caress with passionate warmth, and laid her head down upon her old friend’s shoulder.

“Lois, before I give you this to read, I want you to do something, which, perhaps, you might feel too agitated afterward to manage.”

“What is that, dear madam?”

“You must not call me ‘madam’ or ‘my lady’ any more, pet. I want you to change this fantastical dress for your black silk, and wear my pretty jet ornaments, and also a pair of my white gloves, with the black silk embroidery which I bought in Paris. I think it is a mark of respect you owe to your benefactor. Did you ever see or hear of him?”

“Never, madam.”

“Shall I ring for Justine to help you in dressing?”

A faint smile dimpled the corners of the young girl’s lips as she shook her head.

Lady Quaintree looked about for the bell, then laughed at her own forgetfulness. From this little chamber—formerly a small dressing-room—there was no communication with the servants’ domain. Her ladyship, taking the[Pg 38] copy of the will with her, crossed to her own apartment, only a few steps distant.

When she returned, she was followed by her waiting-maid, who was carrying a package of black laces; a pair of gloves; a filmy lace handkerchief, on which was some black edging; and a black fan—one of Lady Quaintree’s treasures, for it had once belonged to Marie Antoinette.

In those few minutes Lois had thrown off her cloudy robes, divested herself completely of her assumed character of Undine, and donned a handsome black silk evening-dress.

Lady Quaintree was carrying a black-and-gold case, which she placed upon the dressing-table and opened. It contained a complete set of jet ornaments.

She ordered Justine to unfasten the black lace already upon Miss Turquand’s robe, and replace it by that in her custody.

The black lace selected by Lady Quaintree was, Justine knew, very valuable, and the richest she had; the jet ornaments, she also knew, her ladyship prized; so, great was her secret amazement not only to see Miss Turquand habited in black, when the blue and white she had meant to wear was lying outspread upon a couch, but at the lively interest displayed by Lady Quaintree in the somber metamorphosis, and perhaps, above all, at the fact of the stately dame being in Miss Turquand’s apartment.

The discreet Frenchwoman, however, said not one word; but, taking out needles and thread from a “pocket-companion,” she dexterously obeyed the orders received from her mistress.

Lois was so astounded by the news she had heard that she was incapable of doing anything but what, in fact, she had already done, implicitly followed directions. She permitted Lady Quaintree to clasp the jet suite upon her neck and arms, and in her ears, and looked at the gloves, and handkerchief, and fan with the glance of one walking in her sleep.

Justine, wondering, though she did not utter a syllable, was dismissed, and Lady Quaintree desired Lois to sit down.

“We have already been absent nearly twenty minutes,”[Pg 39] she said, consulting her tiny watch. “I wished to arrange your toilet before I told you what is really in this will. Perhaps you think I treat you as a child; but you are already agitated, and when you know the eccentric nature of the conditions, you will, probably, be much startled. Pray read it, my dear.”

Lois did so, with changing color and flashing eyes. When she finished, she threw the paper upon the table, and, rising from her chair, walked to and fro, as if under the influence of uncontrollable emotion. Then she abruptly paused before Lady Quaintree, extending her hands as if in protest.

“Why should this person,” she exclaimed, “of whom I never heard—of whom I knew nothing till this hour—why should this stranger have left me all this money, and why bind me with such conditions? I feel as if I could not, ought not, to accept the gift he has given me. He must have been a lunatic!”

“Softly, softly, softly, my dearest! You are talking at random.”

“How can I face that man again?—he must know, of course,” Lois continued vehemently, referring to Paul Desfrayne.