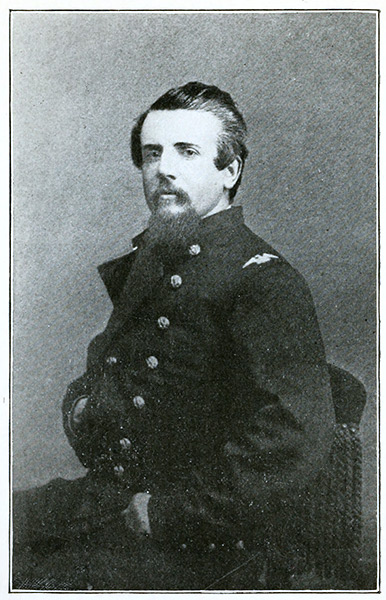

CHARLES F. MANDERSON

Colonel 19th Ohio Infantry.

Brevet Brigadier General Volunteers, U. S. A.

The Twin

Seven-Shooters.

CHARLES F. MANDERSON

Colonel 19th Ohio Infantry.

Brevet Brigadier General Volunteers, U. S. A.

BY

CHARLES F. MANDERSON

LATE COLONEL 19TH OHIO VOLUNTEER INFANTRY, BREVET

BRIGADIER-GENERAL VOLS., U.S.A.

F. TENNYSON NEELY

114 Fifth Avenue

NEW YORK

96 Queen Street

LONDON

Copyright, 1902,

by

CHARLES F. MANDERSON,

in the

United States

and

Great Britain.

Entered at Stationers’ Hall,

London.

All Rights Reserved.

The Twin Seven-Shooters.

[Pg i]

“We came into the world like brother and brother,

‘And now let’s go hand in hand, not one before another.”

—Dromio, in “Comedy of Errors.”

The telling of this truthful story of the Great War comes from the numerous requests of comrades, who knew somewhat of the presentation, the capture and the return of the pair of revolvers that came together after a quarter of a century of separation and after they had been carried and used under two flags. Their restoration could not have been had under any other condition than that which came about at the close of our gigantic struggle.

The Civil War was waged on both the Federal and Confederate sides with an intensity and manly vigor characteristic of [Pg iv]the race that sprang from the loins of the Puritan and the Cavalier.

The immense hosts that combated upon so many dreadful fields, with the incident sacrifice of life and limb, while actuated by the desire to win, by comparison with which individual loss counted as nothing, were never prompted by personal hatred or ill will. They fought to obtain the result desired, and when the end came, with its feeling of exultation by the one and of depression by the other, there was mutual respect and common consideration, that led naturally to a reunited country and the placing of the Great Republic in its present position as the Chiefest of Nations.

The story permits a description of two great battles—that of Murfreesboro, or Stone’s River, and of Chattanooga, or Mission Ridge—the first-named one of the [Pg v]hardest fought fields of the War, and the last, one of the most spectacular. The recital of these calls for no explanation, and I hope the personal equation of the story needs no apology.

Charles F. Manderson,

Late Colonel, 19th Regiment Ohio Infantry.

B’v’t Brig. Gen. Vols., U.S.A.

[Pg 5]

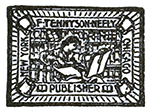

“Resting quietly in their polished case of dark mahogany with its soft lining of tufted crimson silk.”

Resting quietly in their polished case of dark mahogany, with its soft lining of tufted crimson silk, they look harmless indeed and as though their lives had been uneventful. Yet, could they speak with other tongues than those of fire and smoke, they could tell a tale to interest and thrill—of scenes of bloody encounter and deadly strife, of combat and carnage, of victory and defeat, of raid and destruction, of pursuit and capture, of loss and recovery, of separation and reunion,—in short, the exciting story of war, and the captivating tale of peace.

You take up the pair of revolvers with a new interest. Yes! they are handsome. [Pg 6]Shapely and well proportioned, they deserve your exclamation of admiration. The blued steel of barrels and cylinders contrasts attractively with the silver mounting of the handles, so well fitted to the grasp.

“You take them in hand!

You glance along the sights!”

You take them in hand! You glance along the sights! Ah! my friend, time was when the threatening glint of the eye that brought these sights in line was quite different from the gentle light in yours. And now you read inquiringly the inscription, showing the presentation, deeply engraved upon the silver handle band of each seven shooter. Yes, I am the regimental commander to whom they were presented, by the braves of the gallant 19th Regiment of Ohio Infantry, nearly forty years ago. I had lived but little over half that many years, when they came to me and, since the date you read upon them, I have grown grizzled.

[Pg 7]

The scene of the presentation, the causes that led to it and the after events of note, are as vivid as though they were of yesterday and yet there is the strange feeling as though I spoke of some other and not of myself. I take it that most of us who served through those four momentous years of gigantic war now feel as though the experiences were those of a third person, of whom we had knowledge, intimate indeed, but with whom we had not identity. As you ask for the story, it shall be given unto you.

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Prologue | 5 |

| SCENE I. | |

| The Battle | 9 |

| SCENE II. | |

| The Presentation | 24 |

| SCENE III. | |

| The Capture | 29 |

| SCENE IV. | |

| The Reunion | 44 |

| Epilogue | 51 |

[Pg 9]

The Twin Seven-Shooters.

The recital will start fairly on Christmas day of the year 1862, near Nashville, in the camps of the Army of the Cumberland, then commanded by General Rosecrans.

The festive holiday time had increased the usually present disease, until home-sickness was the all-pervading complaint. As the picket peered through the gloomy air under the dull, wintry sky, he saw, in his mind’s eye, the dear ones at home, gathered about the yule-log. The sentry’s thoughts were far away, as he challenged the approaching [Pg 10]guard, that brought relief, but gave none save in name, and received the sharp replies, so different from the words of good cheer properly incident to the time. The men gathered about the camp fires during the evening hours with abortive attempts at merriment, soon to be given up, and then to talk in whispers of friends and family and home. The bugle calls, holding out the promise that balmy sleep might bring forgetfulness, were welcomed; although tattoo seemed a wail, and lights-out a sob.

The restless quiet of a great military camp comes at last. A nest of sleeping souls, it heaves with sound. The sentinels look like stalking ghosts.

After midnight the dreaming sleepers are disturbed by the clank of the sabre of the orderly, seeking the headquarters of regiments to deliver an important order. Be [Pg 11]quick! Light the candle stuck in the bayonet shank at the head of the ground bed where lies the regimental commander.

Ah! Here is a Christmas gift with a vengeance! Read!

“You will place your command in readiness to march at daylight. Move very light—three days’ rations in haversacks and two days’ in wagons. Forty rounds of ammunition on each man, with all the reserve ammunition in wagons. Take no tents and no baggage.”

A battle order! Up and be stirring, for there is much to be done before daylight. Sleepers are aroused, their dreams of home and its festivities rudely disturbed, tents are struck and rolled, and, with the baggage and surplus stores packed into wagons to be sent within the earth-works of Nashville.

Reveille finds the Army of the Cumberland, [Pg 12]nearly fifty thousand strong, on the march to attack the Confederates under Bragg at Murfreesborough, thirty miles away. No holiday march this, I assure you. The enemy is alert. He harasses our front with artillery, attacks our flanks with infantry and harries our rear with cavalry. The elements seem in league with him, for snow, sleet and rain make heavy roads, at which men swear and in which wagons and artillery flounder and stall.

Four days of skirmishing and hard marching, with four nights of unrest and chilly misery bring us to our objective—the enemy. He has selected his battle ground on the bank of Stone’s River, a swift stream, in places fordable.

The night of December 30th we slept, or essayed to sleep, upon our arms, without fires. Never can I forget the dispirited and [Pg 13]woe-begone look of the men as, rising from the frozen ground, they shook themselves at daylight. The hoar-frost covered them, giving to the uniforms of blue a new color, resembling somewhat the grey of the foe. Is there fighting quality in this line of shivering men? Can the battle fire be kindled in these chilled frames? A cold breakfast from the haversacks, a tin cup of coffee to each man, a warming drill in the manual of arms and their appearance is changed for the better.

The order comes! We are to cross Stone’s River at the lower ford and lead the attack upon the enemy’s right. Rosecrans will strike with his left.

An inspection of the guns, a distribution of ammunition, filling both cartridge boxes and haversacks, some words of encouragement and cheer from the youthful commander, [Pg 14]and we move to the river bank, to find our crossing, by wading the cold stream, unopposed by the enemy. We form in line of battle upon the other side and are about to advance to the attack, when the sound of cannon, heard but faintly from our right a short time ago, becomes louder and more loud. A terrific battle is raging there and the movement of sound means our men are being driven. We are halted. There is stir and excitement among the division staff. We are ordered to recross the river and hasten to the support of the right wing.

Bragg, actuated by the same motive as Rosecrans, conceiving the same plan, had attacked our right, but his fresh and sheltered troops struck their blow at an earlier hour. They doubled our line back upon itself. They took our straight bar of iron [Pg 15]and bent it into a horse-shoe. Our right flank had become our rear.

Defeat seemed imminent. On our hurried way, the 19th Ohio, leading Crittenden’s Division, met horses, teams and men in confusion most confounded. Rousseau, of Kentucky, riding bare-headed, cries to me, “What troops are these?” and to my answer says, with tearful entreaty in his voice, “For God’s sake! get quickly to the cedars on our right and stop this rout.” We hasten on. Rosecrans, pale with anguish of the thought that Garesche, bosom friend and Chief of Staff, had just been killed by his side, but determined of purpose and confident in bearing, says, “Men! you can save the day. Will you do it?” “Aye! Aye! sir; if mortal men can, we will!”

We pass from the march by the flank into line under the direction of the Commanding [Pg 16]General himself, my regiment forming the right of the front line.

The grey coats, flushed with success that is so near victory, came gaily on. We wait until they are within easy range. It is a weary waiting and hard to endure. Our men are falling rapidly under the fire of the advancing foe. My favorite mare drops dead with a ball through her gentle heart. Adjutant Brewer, always alert and devoted replaces her with his good grey. Rising from the ground, with no great bodily harm, although I had been pitched headlong, I exclaim: “But, Adjutant, my glasses are broken into many bits and I see dimly.” “Never mind; I will see for you,” he quickly responds. And so he did. Gallant fellow! Brave heart! He gave his young life to his country and his parting benediction to me [Pg 17]afterwards, in a desperate mêlée and fearful charge.

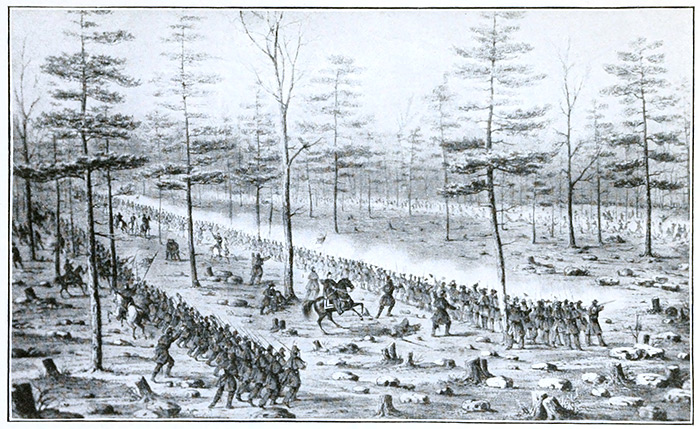

Charge of General Van Cleve’s division in the cedars, at the battle of Stone’s River, under direction of General Rosecrans.

The 19th Ohio Infantry forming the right of the front line. Photograph of a picture made during the war by Private Mathews, of the 31st Ohio Infantry.

At last the order to fire! From every musket leaps a missile of death. The Confederate line wavers! Strong young teeth tear the cartridges. We load and fire with energy. The grey line breaks! A charge is ordered by Rosecrans in person. They run! How inspiring! What exhilaration! With wild yells we rush on. We regain much of the ground lost in the early morning and hold it fast and firm.

Again the nightfall, the last of the eventful year. What horrid din, of cannon and of watchful picket’s gun, to disturb and harass the weary unharmed, who seek to sleep. How cold and miserable the wounded in blue and grey who groan and moan between the lines, where succor cannot come.

Morn at last! The new year has come. [Pg 18]Both armies are so torn and shattered that the re-forming of lines and watchful rest is a necessity. The day passes in care for the wounded and hasty burial of the dead.

Another night, and again the morning. Who will strike the blow? Rosecrans, tenacious of purpose, returns to his original plan. Again our division fords Stone’s River in front of the enemy’s right. The shortened line of each regiment tells the story of the slaughter of the 31st. We wait patiently the order to strike.

The hours pass. Few in number, our division is a tempting bait to Bragg. General Breckenridge, with a column of many lines, advances upon us. With precision of movement they march across the open fields. The sight fascinates us! Splendid spectacle! They break the charm by opening fire and charging upon us with the shrill yell of [Pg 19]the South. With a crash the lines meet, to mingle a moment and break apart. Our reserve becomes our front line. We fight for minutes that seem hours, with bayonet and clubbed musket, with deep cursing and loud yells, with hot rage and bold defiance, that rarest of happenings in battle comes to us—a hand to hand fight between lines of infantry upon an open field. We are overwhelmed by numbers and flanked by the greater force. Thrice has our color bearer been felled to earth, and of all the color guard not one is unhurt.

But the regimental flag does not touch the ground. Gallant Phil Reefy, Lieutenant of Company F, strong and stalwart, bears it aloft. Sullenly we retreat to the river bank, fighting as we retire. We reach the stream.

What is that deafening roar? It is as [Pg 20]though heaven and earth had come together. Fifty-two guns, massed by Mendenhall, Chief of Artillery, commanding the position we had just left, have opened with grape and canister at short range upon the but now exultant foe. What dreadful slaughter! Masses of men fall writhing as the missiles hurtle through the air. They turn and flee, for mortal men cannot withstand such storm.

We pursue until darkness comes, capturing prisoners, guns and stores, and Reefy, proudly exultant, plants the flag of the 19th Ohio upon two cannon captured in the tempestuous pursuit.

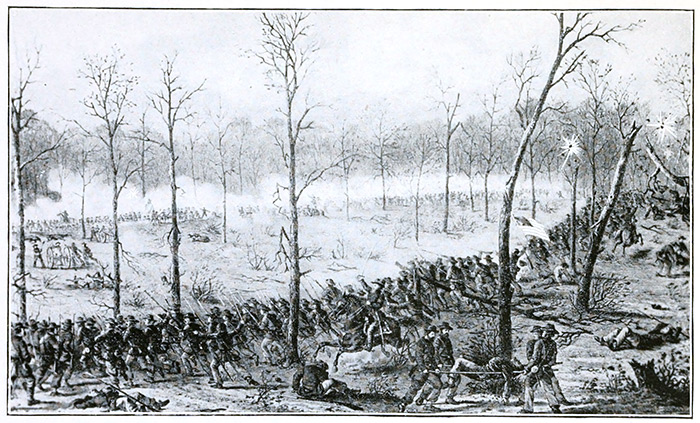

Repulse of the attack of the column of General Breckenridge, being the closing scene of the battle of Stone’s River.

Made from a picture drawn by Private Mathews, of the 31st Regiment, Ohio Infantry, during the war.

No battle of the war shows the dash, pluck, bravery and endurance of the American soldier better than Stone’s River. The attack, so spirited and bold, upon the right wing, under McCook, in the gray dawn of [Pg 21]that winter morning, that forced it back until the exultant enemy was not only on our flank but in our rear! The speedy taking of new positions by the troops of the left wing, under Crittenden; their gallant and successful charge in the cedars that regained much of the ground so ruinously lost!

The sturdy and immovable stand of the center, under Thomas, that resisted assaults most impetuous and broke the charging columns into disorganized fragments, as waves are broken on a rock-bound coast! The dash of the Southerners in attack, the steadiness of the Northerners in resistance, the impulsive ardor of the one, the deliberate repose of the other; both so characteristic! The bold front, the confident daring, the personal exposure, the actual leadership, and the unconquerable spirit of Rosecrans, that [Pg 22]“plucked victory from defeat and glory from disaster!”

All this, any of this, was worth the sacrifice of life itself to see.

It stands in history as a bright page. The dreadful figures of loss tell the story of how terribly sanguinary were the engagements when Americans fought each other. Of 44,000 Federals, 12,000, and of 38,000 Confederates, 10,000 were killed and wounded—over twenty-five per cent. Recall the fact that at Waterloo, Wellington lost less than twelve, and at Marengo and Austerlitz, Napoleon lost less than fifteen per cent.

At daylight the next morning, after the battle, my line was formed. Shorn was it of half its length, for forty per cent. had fallen. Three officers were killed and three wounded. Company B, with more of its own dead to bury than there were unhurt survivors to [Pg 23]do them honor. Ah! the familiar faces gone from us. We who were left looked upon each other with feelings unknown before. We felt a kinship stronger than brotherhood, as though we were parts of one body.

We heard read, with infinite satisfaction, of the glory of our achievements, the congratulations of the General and the thanks of President Lincoln. We shook hands with each other that we had been specially mentioned in the reports, and took satisfactory delight that the commander of the 79th Indiana had officially reported that the good behavior of his command might be attributed to the splendid conduct of the 19th Ohio, and to the effect of our example.

We were heroes all, and were proudly conscious of the fact.

[Pg 24]

The restful weeks following the great battle go slowly by. The ranks of the regiment fill up from the return of the slightly wounded and the detached. The white tents about Murfreesborough, placed in regular rows, form a new city of vast extent. Camp duties, drills, inspection, review, guard mounting and dress parade fill the busy hours. The fighting giant is in training for the summer campaign of Tullahoma and the advance into Georgia.

I recall the afternoon of a perfect day in the early spring time. Parade over and dismissed, [Pg 25]by some preconcerted signal, to me unknown, the first sergeants do not march the men to quarters, but go to their positions and company commanders take their places in line. “Attention! Battalion!” shouts Major Stratton, assuming the command. I look on somewhat amazed at this sudden devotion to a drill not down in the camp orders.

The battalion forms square. I am invited to it, and with speech all too complimentary and feeling reference to the great battle, its losses and its gains, am presented with the beautiful weapons you here admire.

The surprise is only excelled by my delight with the gift. They shall be worn with pride, they shall be used in honor.

I cherish them for the sake of the givers, and practice to know how and to become worthy to use them. They stand me in good [Pg 26]stead very often, and familiarity with them does not breed contempt of their power.

Months go by. The Tullahoma campaign has been fought to a finish. On ostensible recruiting service, but really for participation in the momentous Brough-Vallandigham campaign in Ohio, the opportunity is afforded me to go home for a brief season. I avail myself of it, and take proudly home to show to friends the gift of comrades beloved.

The duty in the north performed, I turn south to rejoin the command. The military situation is most interesting. Like the sharp end of a lance, the western army has pierced into the very vitals of the Confederacy. Rosecrans has won his objective, Chattanooga; paying therefor the bloody penalty of Chickamauga, but is practically besieged by an enemy whose camp fires light [Pg 27]the many miles of horizon, from where the crouching lion of lofty Lookout Mountain, with extended paws, touches the Tennessee, around the semi-circle of frowning ridges to where the strongly intrenched line again touches the deep flowing river at Tunnel Hill. He is relieved from command by the powers that be, and Thomas, the reliable, the Rock of Chickamauga, beloved of all men, takes his place as chief. He declares his intention to hold his great strategic position “until we starve,” and unless help comes, starvation seems probable.

General George H. Thomas

“The Rock of Chickamauga.”

Hooker is on his way from the east with two corps of veterans of the Potomac, and Sherman marches to us with the victorious columns, flushed with the capture of Vicksburg, from the banks of the Mississippi. The great Captain, with the fame of Fort Donelson and Shiloh, comes also, to assume [Pg 28]supreme command. Grant! Sherman! Thomas! Behold the triumvirate! Truly, the great game of war is now to be played by experts. I hasten to take place as one of the pawns.

[Pg 29]

Where the fight was the fiercest at Stone’s River, Captain Keel, of ours, in gallant leadership of his company, was shot in the elbow of his right arm. Surgical skill had prevented amputation and obtained exsection, resulting in a cartilaginous elbow and sorely crippled hand. Thus maimed, he came to me at Nashville and declared his intention of reporting for duty. Condemning his judgment, but admiring his pluck, I said, “All right, Captain, we will take the first train for the front.”

We reached Stevenson, Alabama, the end [Pg 30]of our ride over rough and worn pieces of iron, dignified by the name of railroad. From there a mountain wagon road formed the connection with the army at Chattanooga. Its course could be traced by the fragments of broken wagons, abandoned stores, and by the carcasses of the poor mules, strangled in the mud of it. Trains laden with ammunition, food and forage started daily from Stevenson. The time of their arrival, at the end of the pontoon bridge across from Chattanooga was an unknown quantity. It was at least two and more frequently four days.

My anxiety to reach the regiment was intense. Upon inquiry I heard of a bridle path leading over the mountain and along the bank of the river. By starting early and riding hard, one might get through in a day, but it was the path of danger. The guns of [Pg 31]the Confederates commanded this road, and some of our men had been killed, others wounded and captured, who tried it. I determined to make the effort. The Colonel commanding the post, in response to my earnest appeal, loaned me two horses and an orderly, and we started at the first peep of day.

Keel, too greatly disabled to ride a horse, was to go by the wagon road, taking the baggage of both. He evinced no reluctance when he found that as companions in the same wagon he was to have two estimable women of the Christian Commission, who, with supplies for the sick and wounded, were bound to Chattanooga upon their heaven inspired mission.

Realizing that my route was hazardous, I put on my oldest uniform, stripped myself of all valuables, packing them carefully in [Pg 32]the trunk that contained all of my earthly possessions. Determined that my beloved pistols should not fall into the hands of the enemy, I lodged them securely in my trunk, taking in their stead a pair of common holster revolvers.

The orderly and I rode through without mishap, receiving no shot and seeing but few of the enemy. Arrived at regimental headquarters, I found all well, and received a welcome home that thrilled me. I waited, somewhat impatiently, for the disabled Captain to arrive with the baggage so greatly needed.

The days passed away and gave no sign of him until the fifth after my arrival, when a sorry figure rode to the front of my tent. Seated upon a mule that had upon him parts of wagon harness, was the Captain, a woful figure, with rueful countenance. Don [Pg 33]Quixote appeared not so disconsolate even after his battle with the knights of the windmill. We would have laughed aloud at his sorry plight had his aspect not been so serious. “For God’s sake, food and drink!” he cried. Being properly refreshed, he told his tale of woe. The train of wagons was proceeding slowly along the weary road, when sharp firing at its front evidenced an attack. Wheeler’s cavalry had crossed the river and was on one of the raids in our rear that made the name of General Joe Wheeler one with which to scare teamsters and worry commanders.

The Captain was a man of proper gallantry, a fitting squire of dames, but, withal, not lacking in judicious discretion. The Confederate troopers certainly would not molest the women, bent upon their righteous mission, but to him captivity meant worse than [Pg 34]death. Making hasty excuses, in unceremonious fashion, he jumped from the wagon, pulled a colored teamster off of a mule that he had just cut out of the traces of a wagon, mounted and took quickly to the woods on the side of the mountain. As he plunged deeper into the thicket, he saw in the valley the light of burning wagons, and heard the terrific explosions of ammunition with which many of them were loaded. After days and nights of distress he at last found his way to our camps.

A day or two after, hearing that the female companions of the good captain had reached our lines, I called upon them in the town and heard the rest of the story. Wheeler’s rough riders had treated them with courteous consideration and did not molest their trunks when told that they contained only woman’s apparel. Keel’s baggage and [Pg 35]my own was evidently rich booty. The new uniforms were seized with delight, and my precious seven-shooters appropriated with exclamations of joy and admiration. Taking what was wanted, the residue was thrown back on the wagons, that had been run and piled together, and made food for the flames. The train was but partly consumed when our cavalry appeared upon the scene and a sharp fight ensued, with the result that the women were released from their unpleasant situation.

While the beleaguered army in Chattanooga, foregoing, if not forgetting, the pangs of hunger, echoed the language of Thomas in his telegram to Grant, “We will hold this place until we starve,” it was with right good will that it marched out in front of its works on an eventful November morning, being ordered to make a “demonstration” and relieve [Pg 36]the pressure on Sherman in his effort to take Tunnel Hill, the right flank of the semi-circular natural defense of the enemy, composed of Missionary Ridge, with its crest from five hundred to eight hundred feet above us, around to Lookout on the left with its proud head over two thousand feet above the town. It was a crescent, with defensive works erected with engineering skill, bristling with guns and reflecting threatening lights as the sun played upon the musket barrels and bayonets in the hands of skilled and brave defenders. It looked like the curve of the cutting edge of a huge scimitar.

Map of the battlefield of Chattanooga showing the position of the Confederate Army at Lookout Mountain and Mission Ridge.

A feeling of amity, almost of fraternization, had existed between the picket lines in front of Wood’s division for many days. In the early morning of that day, being in charge of the left of our picket line, I received a turn-out and salute from the Confederate [Pg 37]reserve as I rode the line. But the friendly relation was soon to be rudely disturbed. My pickets, composed of the 19th Ohio and the 9th Kentucky, became the line of skirmishers. Our troops being well out of their works, we advanced with our left resting on Citico Creek, and I believe that from these regiments came the first shots in that glorious advance that resulted in the taking of Orchard Knob, the key of the enemy’s position.

With impatient joy they witnessed the stars and stripes on Lookout’s crest, and heard the guns of Hooker on the enemy’s left. The evidences of the hard fighting by Sherman and the stubborn resistance Bragg’s right was giving him were borne on every wind. The flanking assaults upon the Ridge were not achieving success. There must be another “demonstration” by the [Pg 38]center. Grant stands on Orchard Knob, silently smoking the inevitable cigar. He sees the heavy work to the right and left and that the waning day is showing its lengthening shadows. The center must again relieve the pressure. To Thomas goes the order: “Take the rifle-pits at the foot of the ridge. At the six-gun signal from Orchard Knob, advance the lines to the attack.” Baird, Wood, Sheridan and Johnson were quickly in the order named from left to right.

Restlessly they await the signal. It is well on to four o’clock. At last the sharp report of a cannon from the Knob! Another! and another! and in quick succession the six have thundered forth the order for the charge.

To your feet and forward, men of the Cumberland! “Take the rifle-pits at the [Pg 39]foot of the ridge,” is the order. How splendidly they respond. Adding emphasis to their loud huzzas is the noise of the light artillery on the plain and the deep roar of the big siege guns in the forts of Chattanooga. The crest of the ridge throws its full weight of metal at the lines of blue. The musketry fire from the pits is full in their faces. But neither shot nor shell can stop the impetuous advance. On and on they go, surmounting every obstacle.

The order is obeyed.

The rifle-pits are ours and their late defenders our prisoners. How the grey jackets hasten to the rear. We wonder at their haste, but soon understood it when the guns of the ridge, depressed to sweep the pits, seemed to open the gates of hell itself upon us.

We cannot stay. Must we fall back? Perish [Pg 40]the thought. No! No! No order given, and yet to every man the impulse. Forward the whole line! To the crest of the ridge and take the guns! Every man forward!

Grape and canister from fifty cannon forbid the advance. Wood, Sheridan, Baird, Johnson, Willich, Hazen, Beatty, Carlin, Turchin, Vanderveer, catching the spirit from the men, shout, “Up, boys! To the top!” and grape and canister, wounds and death are forgotten.

On and on and up and up we go, “while all the world wondered.” Grant turns to Thomas, and, with distress if not anger in his voice, says, “Who ordered those men up the ridge?” Replies our old hero, “I don’t know, I did not.” Says Grant, “Granger, did you?” “No,” says Granger, “they [Pg 41]started without orders. When those fellows get started, all hell can’t stop them.”

With hearts in their throats these anxious chieftains watch. The spectators in Chattanooga hold their breath in terrible suspense. It looks a desperate venture, a foolhardy effort. Can they make the top, or will they be driven back to the plain, with columns broken and ranks disordered?

The musketry fire from the intrenched line in grey is murderous. The cannon belch forth incessantly.

“It is as though men fought upon the earth and fiends in the upper air.”

Not a shot from the wedge-shaped lines in blue as they advance with the colors of regiments at the apex of the triangles. Sixty regiments in rivalry for the lead! Colors fall as their bearers sink in death, but other [Pg 42]stout arms nerved by brave hearts bear the flag aloft.

Ah! the lines waver! they cannot make it! But repulse means defeat and loss of all we have gained.

Look! again they go forward! Will they reach the crest? See! the answer! A flag! the nation’s flag! Our flag upon the top! Another, and yet another! The crest breaks out in glory! It is the apotheosis of the banner of the free!

The rebel lines are broken! We are into their works! Cheer upon cheer “set the wild echoes flying” from Tunnel Hill to Lookout! They tell of victory! glorious, exultant victory.

Forty pieces of cannon and 7,000 stand of arms with 6,000 prisoners captured give emphasis to the story.

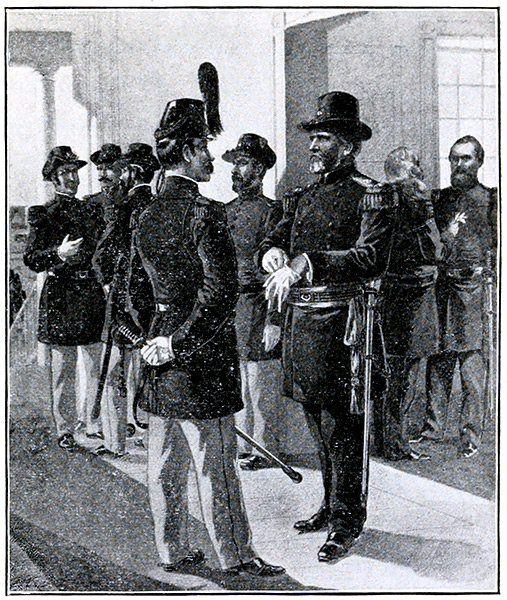

General George H. Thomas and staff after the battle of Mission Ridge.

[Pg 43]

The bars are down for entrance next campaign to Atlanta, gate city of the South.

I went through the starvation siege of Chattanooga, the battles of Orchard Knob and Mission Ridge, and the winter march to relieve Burnside, who was penned up in Knoxville, in very uncomfortable plight, depending upon my brother officers for the clothing to keep me warm, but that which caused me the most distress was the loss, as I naturally supposed, forever, of the twin revolvers that rest now so peacefully before us, reminders of a time of great happenings by the side of which all else in life seems of trifling importance.

[Pg 44]

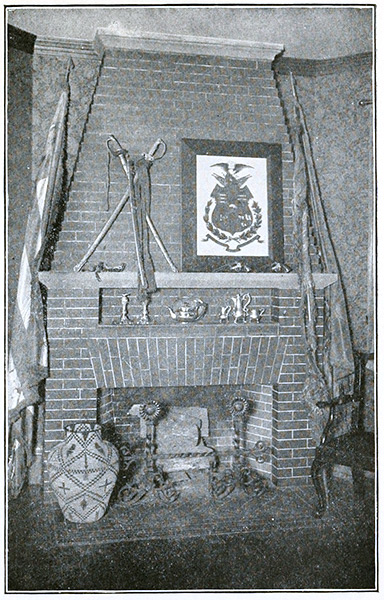

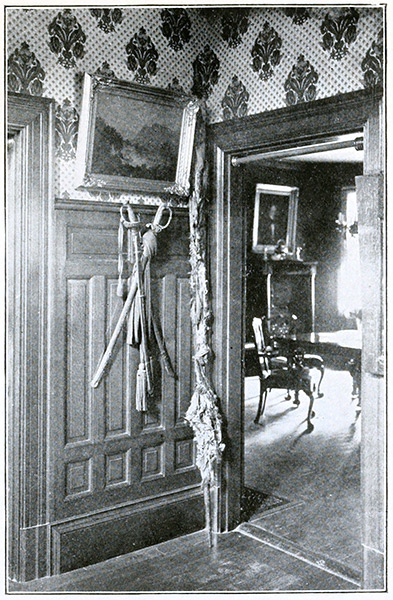

“Upon the wall hung the good sword, with the dent in its scabbard.”

Twenty years passed away, with their changes for good and for ill. The great war seemed like a dream, and its events were dim and shadowy. But there remained to me some substantial evidence of its reality. Upon the wall hung the good sword, with the dent in its scabbard telling of the death struggle of the brave black mare, whose name should be on Stone River’s roll of honor. In the corner stood the regimental flag, presented by my comrades when we parted in 1865, the deep scar upon its staff matching the deeper scar upon the manly [Pg 45]breast of its bearer “in the brave days of old.” I looked at them and longed for the twin seven-shooters that should keep them company.

“In the corner stood the regimental flag presented by my comrades when we parted in 1865. The deep scar upon its staff matched the deeper scar upon the manly breast of its bearer in the brave days of old.”

Representing my adopted State, Nebraska, in the Senate, I had reached a position that had at least given my name notoriety. It chanced that the Major of an Iowa cavalry regiment saw it in the public prints and was prompted to write me. “Are you,” said he, “the man who commanded the 19th Ohio during the war? If so, I have a pistol that must belong to you, for the fact of its presentation is engraved upon it.” I am quick to respond, and in brief time there came the pistol, as welcome to my hand and heart as an old-time friend.

He wrote me its history. During the days of the period of reconstruction he was on duty in Alabama, and upon the person of [Pg 46]a man whom he arrested was found the revolver. The Major took it from him and had held it since, hoping that some time he might meet the owner. Hearty thanks went to him, and I longed all the more for its mate, somewhere existing, but probably never to be recovered by me.

Twenty-eight years elapse after the cavalry raid in the Sequatchie Valley. The Congress is in session and a dreary debate drags its weary length through the hours. My yawning presence in the Senate Chamber would only add emphasis to the dullness there, and I go to the Committee Room, to engage in the usual employment of a Congressman’s spare hours, the dictation of replies to the endless letters, from every direction, on every conceivable subject. There comes a messenger, and this his message: “The compliments of Senator Pugh of Alabama, [Pg 47]who requests the pleasure of seeing you in the Marble Room.” I respond quickly to the call, and go to the room of simplicity and beauty that is one of the chief attractions under the great white dome. Near at hand are three men, two of them well known by me, the third a stranger.

General Joseph Wheeler

“The Marshal Ney of the Confederacy.”

I hasten to greet my colleague, and then shake hands with warmth of greeting with a gentleman I have grown to respect and like. It is General Wheeler, once a dashing cavalry leader of Confederates, he who harried our rear so persistently and pronouncedly; reconstructed into a leader in forensic debate, an authority on parliamentary law, and an all-around legislator, whose trenchant pen was surely as mighty as his vigorous sword. Cuba and the Philippines are the scenes of his later triumphs, and there is no name upon the Army Roll [Pg 48]more honored now for patriotic devotion and soldierly ability than that of him who, during the dark days of the civil strife, was the Marshal Ney of the Confederacy.

I am introduced by the courtly Senator Pugh to his esteemed constituent, ex-Confederate Colonel Reeves, of Alabama. I greet him with pleasure, for he bears upon him those evidences that command respect. Both appearance and speech declare the Southerner, and the soft broad accents fall pleasingly upon the ear. He said, “I think, sir, I have something that once belonged to you, and will give it to you with pleasure, for I presume from the inscription upon it you will prize it highly.”

He produces the long-lost revolver and tells its story. He bought it and its companion from one of General Wheeler’s troopers, who said he captured it at the battle of [Pg 49]Mission Ridge. I mildly suggest that at Mission Ridge the captures were on the other side. He smiled acquiescence and said he cared little at the time of purchase from whence they came, so that they might be his. He had carried them through the war until a fearful wound had disabled him from further field duty.

After the war he had loaned one to the sheriff of his county and from him it had been captured by some of our troops. I told him of the return of that one to me eight years before. We exchange reminiscences of the great struggle. We compare experiences. Enemies in war, we are in peace friends.

Handling his revolver with easy grace and caressing gesture, he makes it mine again, saying as he passes it to me, with pardonable reluctance, “I tell you, sir, that is a [Pg 50]mighty close shooting pistol.” I cordially agree to that sentiment, and we both dwell in thought upon the career of these messengers of death that have fought beneath two flags, giving loyal support to their masters, who have fought each one loyally for his own.

And thus finding each other, after a quarter of a century of separation, they came back to me, to be cherished fondly and I hope never again to be used.

[Pg 51]

And so my friend, you have the truthful story. It is not one to excite special wonder, but causes, I take it, emotions of pleasure and thankfulness.

As the pistols have come peacefully together, so have north and south united in fraternity and in devotion to one flag and a common country. The war taught mutual respect, and never again can there come between these sections the hatred, based upon mutual misunderstandings, that led to the attempt at dismemberment. The men who did the fighting during those four years of bloody war can have no sympathy with [Pg 52]the incendiaries who would array section against section upon any subject. Their motto is bear and forbear. The disposition to fraternize was strong among them even during the strife, and with them now is the brotherhood that is the inevitable incident of unity of national purpose and a patriotic desire for one destiny.

Long ago, while condemning the false teaching that led to the belief that allegiance was to the State, we appreciated how deep abiding was the honest conviction of those who, taught in a different school from us, made untold sacrifice for the cause they espoused.

Forgetting nothing of the past—the cruel blow at nationality, the unhallowed attack upon the flag, with all the sad results of weeping and wounds, of desolation and death—we have forgiven everything.

[Pg 53]

Full citizenship, with all of honor, of governing power, and controlling rights that the term imports, has been accorded to all who participated or lent aid and comfort to the enemies of the Union.

As the victors and the vanquished have recognized equal courage and even powers of endurance, there has come mutual respect. Through the throes and labor of reconstruction, with the contact of peoples, the interchange of commerce, the common interests of the different parts of the national whole, the dovetailing of States through the construction of the iron highways of trade, and mutual contribution of the capital needed for the development of the new South has come peaceful, contented reconciliation. The years that gather wisdom and experience to all long ago taught the lesson even to those who fought for it, [Pg 54]that the cause for which they struggled and suffered was better lost than won.

Hail the epoch of concord! All hail, the era of fraternity!

Let us close the lid of the mahogany box, believing that the pair snugly ensconced within it shall never serve save as polished reminders of other days.

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTES

Extraneous quotation mark on page 11 removed.

Corrected typo in illustration caption “battlelield” to “battlefield”.

Normalized punctuation in illustration caption “CHARGE OF GENERAL....”

Positions of illustrations re-arranged to support the main text.