*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 77707 ***

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

FLOWERS OF PARNASSUS—XXI

A LITTLE CHILD’S WREATH

“Content I leave with God what once I missed.”

A LITTLE CHILD’S WREATH

BY ELIZABETH RACHEL CHAPMAN. WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY W. GRAHAM ROBERTSON ❧ ☙︎ ❧ ☙︎

JOHN LANE: PUBLISHER

LONDON AND NEW YORK

MDCCCCIV

Wm. Clowes & Sons, Limited, Printers, London.

TO

THE HOLY MEMORY

OF

A LITTLE CHILD

AND

TO ALL WHO HAVE MOURNED ONE

9

Introductory Note

Elizabeth Rachel Chapman, whose sonnets are

now republished as a memorial volume, was born at

Woodford, Essex, in February, 1850. She was

descended through her father from a Yorkshire family

associated, in many of its generations, with Whitby,

and was connected through both father and mother

with the Gurneys of Earlham. She was a great-grand-daughter

of Elizabeth Fry, and was said to bear

her a noticeable resemblance. That this likeness was

also in her mind is attested by the “genius for benevolence”

which she inherited from her ancestress, and

by the tenderness of her affection and pity for all

sufferers. In her Book of Sibyls Mrs. Ritchie (Miss

Thackeray) describes the Gurneys of Earlham as

ordained to “a sort of natural priesthood.” Elizabeth

10Chapman was of that company of devoted spirits.

Her love for children was boundless; and the Wreath

was consecrated to the memory of a little nephew,

tenderly loved, in whose grave she now lies.

Miss Chapman’s writings were published between

the years 1881 and 1897; at earlier date appeared

her first work, Master of All, and at the later her last,

Marriage Questions in Modern Fiction. Meanwhile

she wrote what was perhaps her best-known work,

A Companion to “In Memoriam,” which drew from

Tennyson the letter published in the Life: “I am

grateful to you,” he says, “for your book ...

excellent in taste and judgment. I like, too, what

you say about Comtism. I really could almost fancy

that page 95 was written by myself. I have been

saying the same thing for years in all but the same

words.” The passage treats of her perfect belief in

immortality, and her sense of the mockery of life

11without a future. Again, he said that her commentary

on his poem was “the best ever done.” A Tourist

Idyll and other Stories, The New Godiva and other

Studies, and A Comtist Lover and other Studies had

followed each other at intervals of a year or two,

and in 1887 appeared a volume of verse, The New

Purgatory and other Poems. A Little Child’s Wreath was

published in 1894 and reprinted in the year following.

There is a sense in which the simplest things of

literature are the most difficult. The primary and

original griefs and felicities of the heart need to-day

something more than the original emotion, if poetry

is to re-tell them. We know too well the formula in

literature, whereas in the heart there is no formula;

and thus the simple and primitive passion inclines to

be more silent now than at any earlier day. Women

no longer cry out at a funeral, and they say little

when a child dies. The outcry has ceased to reach

12the sensibility of the hearer, and the phrase of grief has

grown relaxed and dull by custom. Therefore it is

with some of the courage of unconsciousness, and of a

grief secluded in its own completeness, that a writer

takes up the old history of the loss of a beloved child.

For this sorrow is so constantly with us—with mankind—as

to have become the ready subject of another

kind of literature. The sentimentalist has used it,

and the sincere mourner, who had at hand only a

sentimentalist’s diction, has vainly essayed to convey

the true feeling in the strained and depreciated phrase.

When Elizabeth Rachel Chapman undertook her

Little Child’s Wreath, she must have been well aware

that two kinds of insincerity—the insincerity of the

sentimentalist, which is insincerity of character, and

that other sort which is merely insincerity of literature,

and may be the disabled utterance of a true heart—had

made much, especially in the course of the

13nineteenth century, of the death of children. But she

forgot or disregarded all this unworthiness, for it can

always be put aside; and freshly and tenderly arranged

her thoughts and rhymed her phrases, writing out of a

heart doubly sincere.

Obviously her work must have been done in the

after-time of grief. Her sorrow for the little boy,

which no mother could have excelled, had grown, when

she began to write, not gentler—for we can hardly

imagine it anything but gentle even in the first speechless

hours—but more able to endure. She had the

literary sincerity which led her to this expression, and

made the craftsmanship of verse a natural exercise in

the leisure of her loss. There is no rhetoric, no mere

borrowing of excessive language, no violence of feeling

or of diction. The laws of poetry, spiritual as well as

metrical, control, or rather direct, the writer’s statement

of love and loss, and she has given the right of this

14discipline to a form of verse—the Shakespearian sonnet—long

neglected, but better fitted than the Petrarchan

to the quantity and quality of English rhyme. The

poems do not profess despair or revolt; they have the

dignity of another spirit, older, newer, and doubtless

more perdurable. Miss Chapman’s studies of In

Memoriam had instructed her in the responsibilities of

a profound affliction.

Slightly, with the slightness of tenderness, she reveals

the portrait of a wonderful child, one of whom the

world was not worthy. His death at seven years old

silenced the doubts, not whether he would be good,

but whether he would be strong, whether he would

have the force, the enterprise to face the strife, to

grapple with the ill. The imminence of death was

evidently visible in him as it has been in so many

children who have died, as it is visible even in an infant

who is not to survive infancy—a greater sweetness, a

15lovelier smile, not imagined by a mother’s memory

after the child’s death, but noted during his life

and during his health, and confessed then as the inevitable

sign of near mortality. The portrait in

A Little Child’s Wreath is an exquisite one of an

exquisite subject; and unconsciously the author—now

that she too has passed from this world we may

say it—has shown her own beautiful and noble soul

to have been marked for a too early, though a later,

passage.

17Our darling loved the meadows and the trees;

Great London jarred him ; he was ill at ease

And alien in the stir, the noise, the press;

The city vexed his perfect gentleness.

So, loving him, we sent him from the town

To where the autumn leaves were falling brown,

And the November primrose, pale and dim,

In his own garden-plot delighted him.

There, like his flowers, he would thrive and grow,

We in our fondness thought. But God said: No,

Your way is loving, but not wholly wise;

My way is best—to give him Paradise.

19

Illustrations

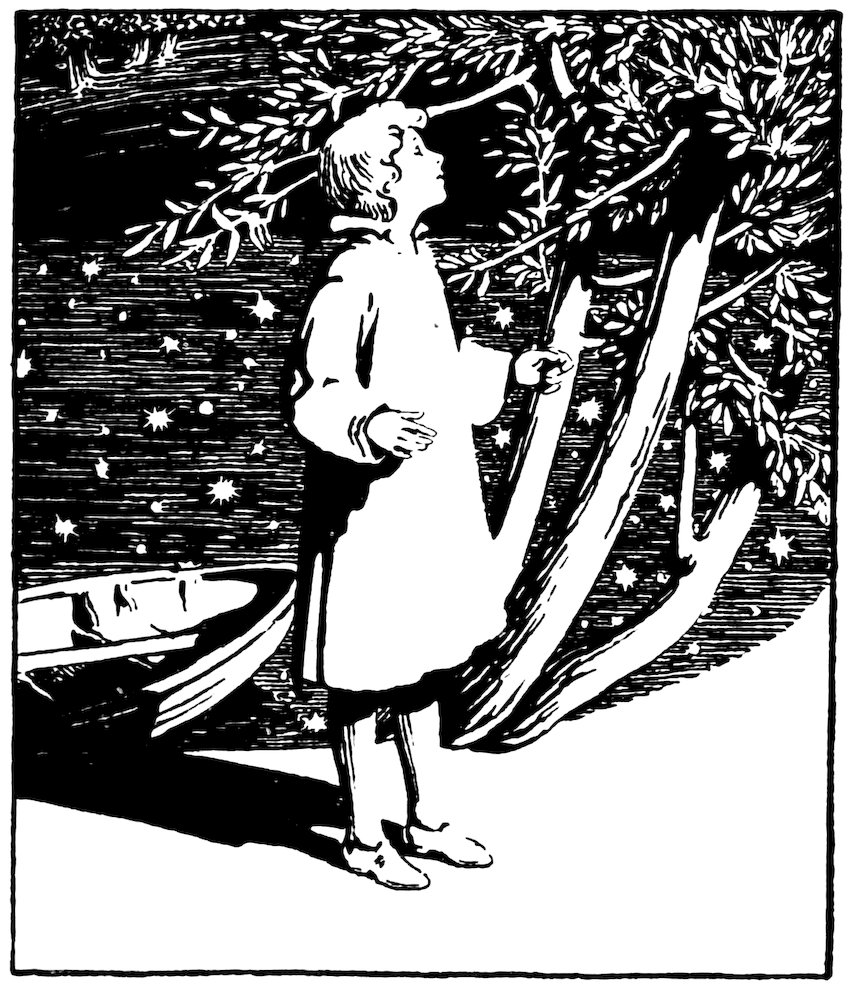

| “Content I leave with God what once I missed” |

Frontispiece |

| “Round me the city looms, void, waste and wild” |

Page 23 |

| “The jocund dance of wind-swept daffodils” |

„ 29 |

| “From heaven to heaven, along an azure sea” |

„ 35 |

| “O’er hill and dale, through waste and wood” |

„ 47 |

| “Or heaven reflected in the serious face” |

„ 61 |

21

A LITTLE CHILD’S WREATH

I.

If, where thou walkest, dear, we too could walk,

Close in the footsteps of our little saint,

Now, on this earth ; and hear the angels talk,

Living this very life (without life’s taint);

If, where thou goest, we could also go,

Calm in the heavenly places, waiting not

For death’s enfranchisement to overthrow

The world in us, with every flaw and blot;

If thy small hands, that late were clasped in pain,

Could clasp us every day to God and thee,

Drawing us childwards, heavenwards again

By their mere whiteness, everlastingly—

Then, humbled and consoled by so much grace,

We might less hungrily desire thy face.

22

II.

Turn where I will, I miss, I miss my sweet;

By my lone fire, or in the crowded way

Once so familiar to his joyous feet,

I miss, I hunger for him all the day.

This is the house wherefrom his welcome rang;

These are the wintry walks where he and I

Would pause to mark if a stray robin sang,

Or some new sunset-flame enriched the sky.

Here, where we crossed the dangerous road, and where

Unutterably desolate I stand,

How often, peering through the sombre air,

I felt the sudden tightening of his hand!

Round me the city looms, void, waste and wild,

Wanting the presence of one little child.

23

“Round me the city looms, void, waste and wild.”

25

III.

They bid me go forget my grief in Art;

But, dear, what art is so aloof and so

Distinct from thee that it can bring my heart

The balm less all-embracing sorrows know?

Most surely not the painter’s; he, alas!

With all the cunning of his craft divine,

But disappoints my sight with what might pass

For beauty—had I never looked on thine.

And music, what can music do but fill

The trembling cup of longing to the brim?

There is no music—save a child’s voice still

Soft singing in the dusk the evening hymn.

My very art, my art of song—ah me!

What is it now but one long sob for thee?

26

IV.

Move through the flames with us, transcendent form,

As of the Son of God, in splendour move!

Divide the anguish, breast with us the storm,

Companion perfect grief with perfect love.

Shine through the burning, more refulgent thou

Than fire with will subdued and mastered pain;

Unharmed sustain us in the furnace now,

And unconsumèd lead us forth again.

Word of the Highest! Mystic effluence

Of That which calms us most, which helps us best!

Compose our hearts, control our shattered sense,

And, in our tribulation, give us rest.

Nerve us to watch the night of weeping through,

Wisely to bear and nobly still to do.

27

V.

When spring comes and the long, unwonted snows

Fade from the shrouded parks, and little green

Adventurous points show where the crocus grows,

And soon the dazzling phalanx will be seen—

Then, in your favourite “flower-walk,” my dear,

Will troops of happy, living children play;

But I the shouts, the laughter shall not hear,

For I, dear heart, I shall not pass that way.

Was it not there that, bounding at my side,

Last year in glorious sympathy with spring,

You the first crocus suddenly espied

With musical sweet cries of welcoming?

In less frequented spots, observed of none,

My steps will stray, bereaved, forlorn, alone.

28

VI.

Our woodland poet who on Nature’s breast

Lay wisely passive through the tranquil years,

Wrote of the comrade whom he loved the best

This praise: She gave me eyes, she gave me ears.

The jocund dance of wind-swept daffodils;

The marvel of the nest the sparrows made;

The secrets of the vales and of the hills

The child had slowlier learned without her aid.

For me, my best instructor in the spells

And wiles of Nature was a seven-years’ boy,

To whom she had revealed the soul that dwells

Beneath her careless outward robe of joy.

She knew him true; she made him one with her,

Her little prophet and interpreter.

29

“The jocund dance of wind-swept daffodils.”

31

VII.

Deep-curving lashes, long and soft and dark;

Deep gentle eyes that late were lit in heaven

With God’s most sacred, most immaculate spark,

To His elect among the children given;

Dark hair, where wistful hands laid on to bless

Might pause, blest rather, overshadowèd

By wings of angels and the blamelessness

That crowned the innocent brow, the gracious head;

A cheek, where tremulous colour came and went,

Transparent, sensitive, and smooth and fine;

Well-chiselled features, mutely eloquent

Of the great Master-workman’s touch divine—

These were the parts that made a perfect whole,

The faultless temple of a spotless soul.

32

VIII.

More than the faith of childhood’s years he had;

He did not doubt the depth of our desire

That he should be perpetually glad,

Nor dream our joy in him could ever tire.

He trusted all the world; the world was kind,

And men and women loving; so he went

To dwell with strangers undismayed in mind,

And smiled, and did not deem it banishment.

In every heart he knew he found a home,

A sanctuary in every human face;

And when God, missing him in heaven, said: Come!

It did not seem a solitary place.

I think he only flushed in sweet surprise

To see the golden floor beneath his eyes.

33

IX.

So docile was my dear, so wise to know

And love the tender rule he should obey,

So childly tractable, withal so slow

To childish wrath, so clean from passion’s sway,

The momentary doubt would sometimes rise

If in the patient child reposed the will

The man would need, the force, the enterprise

To face the strife, to grapple with the ill.

I know not, but I know that manhood’s crown

Was ever meekness, since the children’s friend

Rode humbly royal through the palm-strewn town

Unto a stern retributory end.

I see foreshadowed in that seven-years’ span

The fulness of the stature of a man.

34

X.

From heaven to heaven

[1], along an azure sea,

Fanned by light airs, his little sail was set;

Young angels went with him for company,

And smiles and sunshine all the way he met.

His pretty mates and he had communings

So fair, he could possess his soul in peace,

And scorn to be disturbed by earthly things

And chafed by trivial jars that soon must cease.

Why should he fret who was in sight of port

Before almost he left his native shore,

And did but change a well-beloved resort

For one that would content and charm him more?

His great serenity to him was given

Because his conversation was in heaven.

35

“From heaven to heaven, along an azure sea.”

37

XI.

“Flowers in my garden! Flowers!” Love’s willing thrall,

Responsive ever to her tyrant’s will,

Sped through the house, nor heeded other call,

To where, without, he stood and claimed her still.

“My garden” in the town required the grace

He had to call it such—a dust-grimed square—

But his content emparadised the place,

And made it bud and blossom everywhere.

“Where are your flowers?” I mocked, for all around,

Under the dismal walls, smoke-tainted green,

Dim laurel, sad spent crocus on the ground,

Sad ivy-tendrils, could alone be seen.

But while I mocked, laughing and kissing too—

Lo! three small stems of scylla frail and blue.

38

XII.

Under the flowers he loved my flower lies,

Pansy, and primrose pale, and violet,

And in my heart the season’s sweetness dies,

And all my joy is faded to regret.

My garden, mine, is his new-planted grave,

Beneath the elm where birds, new-mated, sing,

Whose green-tipped branches in the west-wind wave,

And make their glad obeisance to the spring.

Tell me not spring is fair and fraught with hope,

Bid me not go seek solace at her hands!

Spring is my autumn, my year’s downward slope,

And he is lying where the tall elm stands.

My only spring, my only hope is this—

Soon, soon to follow where my treasure is.

39

XIII.

I know not by what sorcery of sleep

Last night I held him radiant in my arms,

Yet knew him soon to die, but did not weep,

That he might think death blesses us, not harms.

In health, in love, in life, it seemed my lot

To tell my lovely dear that he must go

Where we who were so one with him could not,

But needs must linger, if we would or no.

And musing how I best could keep him brave,

And knowing well the hopes and fears of seven,

And well the liveliest joy his heart could have,

I smiled and told him flowers grew in heaven.

But while to his, athirst, my lips I pressed,

The bright face fell; he thought to stay was best.

40

XIV.

“Ill-placed my heart; I love another’s child,”

[2]Sings wistfully, and sighs, a bard of France;

And ah! the hunger in the accents mild,

The pain behind the smiling countenance!

Vexed with the ache of uncompanioned souls,

His playmate at his mother’s side he sees,

And scarce his tender jealousy controls

When swift he springs upon his father’s knees.

Nay, poet, sing for joy, exult and sing!

Thy dear one lives, though not for thee his heart;

He lives, he breathes, he ails not anything;

Watch him and love, and, praising God, depart.

’Tis but his father sweetly rivals thee,

While death, alas! requires my love of me.

41

XV.

When in the twilight, round my lonely room,

Leaving the pictured features that I love,

My sad eyes, aching in the childless gloom,

From one mute image to the other rove,

They dwell with most repose, most solacement

On the fair stripling, strong, erect and calm,

Of Andrea’s dream, from whose sweet lips “Repent!”

Fell soft, I think, like odoriferous balm.

Deep, gentle eyes; pure, finely-moulded mouth,

Like his but now I looked my last upon;

He seems my angel grown to god-like youth,

And my belovèd seems the young St. John.

With even such loveliness of soul and limb

Time and God’s grace would have anointed him.

42

XVI.

Within a petal of the blessed Rose,

Of Dante’s blessed Rose of Paradise,

Sits my belovèd, radiant in repose,

Love on his lips, and laughter in his eyes.

There, with the tender jocund company

Of little hurrying folk

[3] that haste to heaven,

To him the sunshine of the life to be,

To him the perfectness of joy is given.

Above the Flower’s mystic heart of light

His rose-leaf curls, a perfumed, delicate nest,

And whitely folds around his raiment white,

Encircling him in beauty and in rest.

And in and out, like bees, the angels flit,

With stores of bliss that he may feed on it.

43

XVII.

If haply, dear, I may to thee attain,

And be, I too, a child in heaven with thee,

[4]Let me for evermore a child remain,

And where thou dwellest, let my dwelling be.

A childish-lowly seat, but next thine own;

If this, through perfect grace, should be my lot,

I would not climb to any loftier throne,

And loftier hopes I would remember not.

The elder life brought strife, not peace, on earth,

The growing years dismay and hate and feud;

To share for ever thy unconscious mirth—

This were my heaven and my beatitude;

And all the lore that saints and sages teach

Were foolishness beside thy prattling speech.

44

XVIII.

Like Mary’s mother, moving not her gaze,

For all her singing, from her daughter’s smile,

I would give endless thanks, give endless praise,

And look on thee, thee only, all the while.

Close to thy side, my wound made whole again,

I would not raise my eyes to where, serene,

With Rachel, Ruth, and Beatrice, freed from pain,

Sits regal, crowned with angels, heaven’s queen.

I would not even glance to where he stands,

Proud at her feet, while loud his Aves swell,

With wings outspread, intent on her commands,

The mighty Love

[5], God’s herald, Gabriel.

How could I choose but ever feast on this,

To see my heart’s delight again in bliss?

45

XIX.

Where jaded London pauses, climbing north,

For very weariness, and leaves large room

For May in magic vesture to come forth

And spread the hills with fern and yellow broom,

I go to breathe; I go, without my dear,

And think how he, with ball or mimic bow,

Danced up and down the happy slopes last year,

His eye joy-kindled and his cheek aglow.

I hear him call my name; I see the far

Blue distance shine beyond the hawthorn-flowers;

I cry to God to give me back my star,

My sweet, to give me back those golden hours.

How cool upon the heights the breezes blew!

How swift into the air his arrow flew!

46

XX.

At midnight, in my dream, a cry was heard,

As of the bridegroom’s coming. Through the black

And solitary void no echo stirred

Sounded this melody: He has come back!

A little moment, and behold once more

I saw him, as he lived, before me stand,

But to a deeper hue than erst it wore

By largesse of the sun his cheek was tanned.

They said that gipsies had decoyed my love,

And he, o’er hill and dale, through waste and wood,

Where’er such pensioners of nature rove,

Had shared their wandering life and found it good.

In careless joy glad day had followed day;

And that was why he was so long away.

47

“O’er hill and dale, through waste and wood.”

49

XXI.

And wilt thou never feel the hurrying tide

Of virile blood pulse quick along thy veins,

And stand magnificent in manly pride,

And know a man’s fierce joys and glorious pains?

Strong vital thrills that lift the human up,

Transfigured, rapt, to mix with the divine;

Beats of the music, foamings of the cup,

Filled to the splendid brim with youth’s new wine—

These wilt thou never taste—not taste the bliss

Of our mere being, mere recurrent breath,

Mere oneness with the life in all that is,

The cosmic energies that laugh at death—

Not know the moments when some god in us

Seems to exalt and crown our manhood thus?

50

XXII.

And when the god speaks, when potential force

Springs into actual, as the bud to flower,

And, like a storm-fed stream along its course,

Rush the first promptings of creative power;

When from mere man we grow to maker, bard,

Sage, prophet, scholar, artist; scale the heights;

Assume the sceptre; drink the whole unmarred,

Completed draught of richest life’s delights;

When we control and rule, inspire and lead,

Mould laws for men, bid empires feel our sway,

Probe nature’s secrets, wrest them to our need,

Live glorious years in one heroic day—

This full fruition of our human lot

Wilt thou for evermore inherit not?

51

XXIII.

Dying a child, thou wilt not see the birth

Of beauty from the blossom-foam of May

Again at all, or June enchant the earth

With scent of hedge-rose and of new-mown hay.

No more the pageant of October woods

Wilt thou behold, nor feel the mystical

Hushed charm of Nature in her wintry moods

Of weird white silence any more at all.

Unseen by thee to mingle with the skies

The alp shall rear his everlasting snow;

Unhallowed by the wonder in thine eyes

Through the clear heaven the harvest moon shall go;

Unblest by gaze of thine, perennial rills

Breathe answering peace among the little hills.

52

XXIV.

Nor, thus untimely dying, shall the throes

Of mightier births touch thee, afar, asleep,

As back to youth divine the old world grows,

And forward into light the lost truths leap.

Not thine, upborne upon the gathering wave

Of spirit-forces, perfecting the man,

Thy joy to seek, thy crown of joy to have

In newly leading him to Canaan.

The toiler, human-free, and strong in might

And meekness, shall not come within thy ken;

Nor woman rising to her pristine height

Sublime of patriot and of citizen;

Nor that slow loosening of the secular chain

That binds the brutes in dumb, vicarious pain.

53

XXV.

Shall Love not bless thee? Shalt thou ever miss

His mysteries of healing and content,

His balm of Gilead garnered in a kiss,

The bounteousness of his good government?

Lo, where he walks in pureness beauty springs,

And flowers of gladness where his feet have trod,

And all the way from off his rainbow wings

Drop to the earth benignant dews of God.

Who come within his gentle seigniory,

Whom his hand touches and his lips caress

Are straightway set from thrall of evil free,

And proudly tread the ways of righteousness.

Alas! shall Love, the saviour, not draw nigh

At all to thee? Shall he too pass thee by?

54

XXVI.

Again my dear was with me yesternight,

But now his brow was vexed, his eye was dim,

And he distressed and tired, and worn and white,

As when the pains of death gat hold on him.

On the bare deck of some tall phantom ship,

Tossed by rude waves, unnursed and lone he lay,

No tender hand to cool his fevered lip,

No voice love’s little language soft to say.

Amazed with grief to succour him I flew,

And made his hard bed smooth and warm and fair,

And one faint flickering smile of comfort drew,

Which pierced my heart, and still inhabits there.

Yet, waking, grieve I less, dear love! I see

How far more softly Death hath pillowed thee.

55

XXVII.

Fondly the wise man said that foolishness

In a child’s heart was bound, and said the rod

Could perfect that which surelier one caress

Lays, love-baptized, before the feet of God.

And fondly he, the passionate saint who steeped

His virgin soul in Carthaginian mire,

Found in the weanling babe that laughed and leaped,

Glad from its mother’s arm, hate, spite and ire.

They erred. The child is, was, and still shall be

The world’s deliverer; in his heart the springs

Of our salvation ever rise, and we

Mount on his innocency as on wings.

I, at the least, who knew and ever grieve

One little lovely soul, must so believe.

56

XXVIII.

More grateful to the human heart, and more

Wise with the wisdom human mothers earn

By pangs of birth and pains of loss, his lore

Who bade mankind of little children learn.

Pure, he could feel their splendid guilelessness;

Kingly, he recognised their royalty;

Longsuffering, he was one with them, nor less

Grandly magnanimous than they was he.

He dared to judge mankind best fed by truth,

Best led by love, desiring most of all—

Not lures of sin—but grace to walk like Ruth

Where natural ties and home affections call.

And so he “took a child,” with father’s touch,

And therefore said God’s kingdom was of such.

57

XXIX.

A quiet southern bay; a quiet sea

That scarcely breaks along the level sands;

An ecstasy of little children’s glee;

A weight of grief that no one understands.

Slow-moving sails, with curves of grace complete

As ever beauty-loving pencil drew;

A ceaseless play of pretty hands and feet;

A want for ever deep, for ever new.

Peace on the teeming earth, goodwill and peace

In the clear blue and floating cloudlets white;

Crownèd the land with joy of her increase;

Quenched my desire and vanished my delight.

A sea-bird said: I know, I know the pain;

He will not see the summer-tide again.

58

XXX.

Kind little lad, with dark, disordered hair,

Who, friendly-wise, forsake your half-built fort

To make me in the sand a high-backed chair,

So kind, so keen to join the livelier sport—

Haste to your trenches! Fly! To arms! to arms!

The foe prepares to storm your citadel;

Your comrades sound excursions and alarms,

And those stout hands must fight that build so well.

Laugh, happy soul!—nor dream you brought me tears.

His beauty had you not—for that the earth

Holds not his equal—but you had his years,

Almost his eyes, and something of his mirth;

And one stray lock on your bare neck that curled

Made sudden twilight of the summer world.

59

XXXI.

What draws us childwards? Cherub charm and grace,

The frolic kitten and the tricksy elf,

Or heaven reflected in the serious face,

And the divine unconscious of itself?

What art makes magnets of the helpless hands

That fitfully caress and feebly touch,

What sorcery entwines the flowery bands

That chafe so sweetly and compel so much?

For thee I know not, but for me I know;

I know the charm that everywhere, abroad,

At home, and wheresoever I may go,

Enthrones the child my sovereign and my lord.

Not beauty, no, nor grace, nor gleams of heaven;

The passport to my heart is—being seven.

60

XXXII.

I dreamed I did but dream my love was dead,

And all for nought had been my long complaint;

He had come back and stood beside my bed,

Grown tall and straight and fair as Andrea’s saint.

He has come back! Again the tidings rang;

Again my pulses leaped with wild delight;

Again the choric stars together sang,

And joyous pæans sounded through the night.

But with the calm of heaven on me he smiled,

There where in feverish ecstasy I lay,

As on a mother her home-coming child,

When childish things have long been put away.

“’Tis thou art now my care,” looks such an one,

“And I thy stay, thy comforter, thy son.”

61

“Or heaven reflected in the serious face.”

63

XXXIII.

Where loving Francis shed on Umbrian ways

And fruitful slopes of sun-kissed Apennine

The benediction of his cheerful praise,

The oil and spikenard of his speech benign,

I wandered, musing how so dark an age

Had borne a heart so pitying and so sweet,

To whom all bruisèd things made pilgrimage—

All hunted things—to shelter at his feet.

And fancy, wistful-fond, began to paint

A greeting yonder in the far-off land,

And how the merciful Assisian saint

Had taken mine, rejoicing, by the hand;

Not so much glad that he was safe and whole,

As proud to welcome a companion soul.

64

XXXIV.

The lowliest timid creature that had life,

Had from the prophet tenderest look and word;

He saved the lambs from torture and the knife,

And bare them in his bosom like his Lord.

While furious men through blood to greatness won,

And women’s eyes with weeping still were wet,

He taught his “sister birds” their antiphon,

Or fondled “little brother leveret.”

Now in his native heaven serene he moves,

With comrades wise, benignant, courteous, kind,

With whatsoever succours, yearns and loves,

With men of godlike and of childlike mind;

And near him walks, familiar and at ease,

My angel-love, for he too was of these.

65

XXXV.

With him too gracious Pity made her home,

And furled her sad soiled wings in sweet content,

Forgetful that it is her lot to roam

From age to age in woeful banishment.

His small heart seemed to her no narrow space,

But, like God’s many mansions, wide and fair;

And so she chose it for a resting-place,

And hospitably she was harboured there.

And grateful for the boon, she taught him lore

Of heaven, and how the tender angels know

The merciful are blest for evermore,

Although the wise and prudent say not so;

And how God holds him least among the least

Who is not pitiful to bird and beast.

66

XXXVI.

Superbly still they vaunt their ancient pride,

Those lofty eyries of old Italy

That ruled the land when Francis lived and died,

Glorious in might, erect, and fair to see.

Perugia’s portals and Siena’s towers,

And dear Assisi’s walls that shine afar,

What seem they to this distant age of ours?—

Lairs of fierce men that took delight in war.

Yet, while we deprecate, our Europe groans

Beneath her armaments the livelong day;

Her peoples cry for bread—we give them stones,

And crush and curse with mailèd peace alway;

And still to Moloch babes are sacrificed

By men that call upon the name of Christ.

67

XXXVII.

Yea, lonely still and evermore without,

Shamed and forgotten by the weed-grown door,

Standeth the Christ, while rings the battle-shout,

While statesmen wrangle and while madmen roar.

Spurned is the lord of peace, his message spurned

As when his people thorns for solace gave;

As when Servetus or when Cranmer burned,

Or England dared to side against the slave.

Hark! from the savage wilds they go to tame

Hark, what discordant sounds affront the ear!

His very priests, contending in his name,

Make it a thing of hate and scorn and fear.

Only the child his loving liegeman is,

And lays a timid hand, consoled, in his.

68

XXXVIII.

Blest are the trusting eyes that close in sleep

Or e’er the soilure of the world they see;

And blest art thou—I feel it while I weep—

Yea, well is thee and happy shalt thou be.

Blest is the guileless heart that never guessed

How faith is tainted and how love defiled,

But only knew them fresh from God and dressed

In whiteness in the fancy of a child.

Blest is the voice that never strove nor cried,

Nor swerved from truth, nor raged in vain desire;

Blest is the hour in which our darling died,

Saved from the evil, rescued from the fire.

Bow we the head; cease we the piteous knell;

God is the judge, and doeth all things well.

69

XXXIX.

I do thee wrong to mourn thee; I blaspheme

The Power that gave thee joy, that gives thee rest,

And while I chafe and fret, and sigh and dream,

Lulls thee in slumber on its sheltering breast.

This earth was not for thee, oh, not for thee

The turmoil and the wearying storm and stress,

The hungering hope deferred for good to be,

The mocking shows, the maddening lovelessness.

Thou spirit-child, for soothing formed, not strife!

Thou gracious tender joy an instant given!

Thou didst but beautify and bless our life

A little while to perfect us for heaven;

And see, for us hath life become a prayer

That we may merit grace to meet thee there.

70

XL.

Rest, little love! rest well, my heart’s desire!

Sleep while the storm-winds blow, the furious rage;

Sleep till the foes of God and goodness tire;

Sleep till the earth fulfils her pilgrimage.

Sleep where the slender snowdrop bells in peace

Kiss the small crystals off the hoary grass;

Sleep where all angry things and hurtful cease,

Where calms brood ever and where tempests pass.

Hushed by the gracious hand of pitying death,

I hush thee too with my low song of praise;

Thou gentlest thing that ever yet drew breath,

My thanks for this thy rest to heaven I raise!

Content I leave with God what once I missed,

And keep upon thy grave my Eucharist.

Flowers of Parnassus

A Series of Famous Poems Illustrated

| Size 5½ × 4½ inches, gilt top |

| Price 1/- net |

Bound in Cloth |

Price 50 cents net |

| Price 1/6 net |

Bound in Leather |

Price 75 cents net |

- Vol. I.

- GRAY’S ELEGY AND ODE ON DISTANT PROSPECT OF ETON COLLEGE. With Twelve Illustrations by

J. T. Friedenson.

- Vol. II.

- THE STATUE AND THE BUST. By Robert Browning. With Nine

Illustrations by Philip Connard.

- Vol III.

- MARPESSA. By Stephen Phillips. With Seven Illustrations by Philip Connard.

- Vol. IV.

- THE BLESSED DAMOZEL. By D. G. Rossetti. With Eight Illustrations

by Percy Bulcock.

- Vol. V.

- THE NUT-BROWN MAID. A New Version by F. B. Money-Coutts. With

Nine Illustrations by Herbert Cole.

- Vol. VI.

- A DREAM OF FAIR WOMEN. By Alfred Tennyson. With Nine

Illustrations by Percy Bulcock.

- Vol. VII.

- A DAY DREAM. By Alfred Tennyson. With Eight Illustrations by

Amelia Bauerle.

- Vol. VIII.

- A BALLAD ON A WEDDING. By Sir John Suckling. With Nine

Illustrations by Herbert Cole.

- Vol. IX.

- RUBÁIYÁT OF OMAR KHAYYÁM. Rendered into English Verse by Edward

Fitzgerald. With Nine Illustrations by Herbert Cole.

- Vol. X.

- THE RAPE OF THE LOCK. By Alexander Pope. With Nine Illustrations

by Aubrey Beardsley.

- Vol. XI.

- CHRISTMAS AT THE MERMAID. By Theodore Watts-Dunton. With Nine

Illustrations by Herbert Cole.

- Vol. XII.

- SONGS OF INNOCENCE. By William Blake. With Nine Illustrations by

Geraldine Morris.

- Vol. XIII.

- THE SENSITIVE PLANT. By Percy Bysshe Shelley. With Eight

Illustrations by F. L. Griggs.

- Vol. XIV.

- ISABELLA; or, THE POT OF BASIL. By John Keats. With Illustrations.

- Vol. XV.

- WORDSWORTH’S GRAVE. By William Watson. With Illustrations by

Donald Maxwell.

- Vol. XVII.

- LYCIDAS. By John Milton. With Eight Illustrations by Gertrude Brodie.

- Vol. XVIII.

- LINES COMPOSED A FEW MILES ABOVE TINTERN ABBEY. By William

Wordsworth. With Eight Illustrations by Donald Maxwell.

- Vol. XIX.

- THE BUILDING OF THE SHIP. By Henry Longfellow. With Eight

Illustrations by Donald Maxwell.

- Vol. XX.

- THE TOMB OF BURNS. By William Watson. With Nine Illustrations by

D. Y. Cameron.

- Vol. XXI.

- A LITTLE CHILD’S WREATH. By Elizabeth Rachel Chapman. With an

Introduction by Mrs. Meynell, and Illustrations by W. Graham Robertson.

- Vol. XXII.

- THE DEFENCE OF GUENEVERE. By William Morris. With Eight

Illustrations by Jessie M. King.

- Vol. XXIII.

- KILMENY. By James Hogg. With Eight Illustrations by Mary Corbett.

- Vol. XXIV.

- ODE ON THE MORNING OF CHRIST’S NATIVITY. By John Milton. With

Eight Illustrations by J. Collier James.

- Vol. XXV.

- THE BALLAD OF A NUN. By John Davidson. With Eight Illustrations

by Paul Henry.

- Vol. XXVI.

- RESOLUTION AND INDEPENDENCE. By William Wordsworth. With Eight

Illustrations by Donald Maxwell.

JOHN LANE, London & New York

- Typos fixed; non-standard spelling and dialect retained.

- Used numbers for footnotes.

*** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 77707 ***