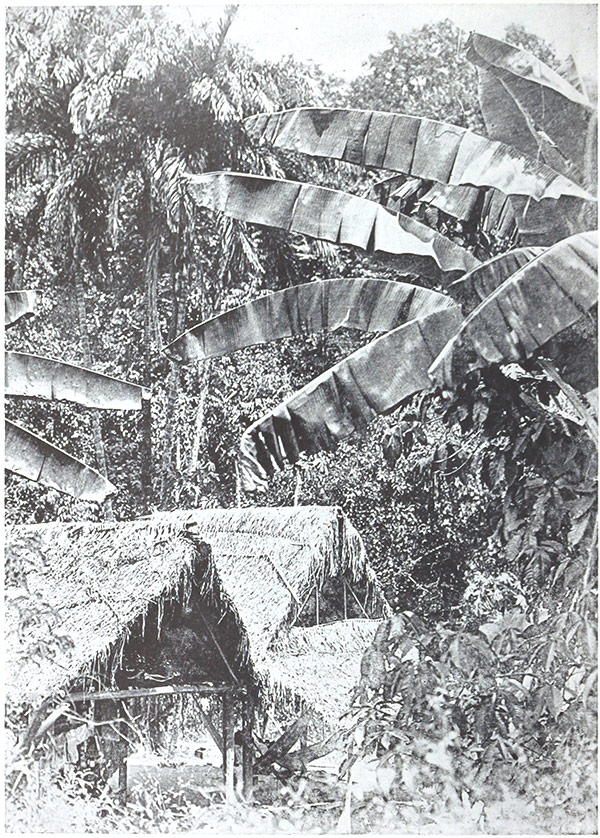

Indian Hut on the Mazaruni River

Indian Hut on the Mazaruni River

[Pg i]

BY

WILLIAM BEEBE

AUTHOR OF

“GALÁPAGOS: WORLD’S END,” ETC.

∽

Illustrated

G.P. Putnam’s Sons

New York & London

The Knickerbocker Press

1925

[Pg ii]

Copyright, 1923

by

The Atlantic Monthly Co., Inc.

Copyright, 1925

by

The Curtis Publishing Co.

Copyright, 1925

by

William Beebe

Made in the United States of America

[Pg iii]

| CHAPTER | PAGE |

|---|---|

| I.—A Chain of Jungle Life | 3 |

| II.—My Jungle Table | 26 |

| III.—A Midnight Beach Combing | 49 |

| IV.—Falling Leaves | 71 |

| V.—The Jungle Sluggard | 92 |

| VI.—Mangrove Mystery | 113 |

| VII.—The Life of Death | 137 |

| VIII.—Old-Time People | 166 |

| IX.—The Bird of the Wine-Colored Egg | 182 |

|

FACING PAGE |

|

|---|---|

| Indian Hut on the Mazaruni River | Frontispiece |

| “And there was a Grandmother Frog” | 14 |

| “Well Within the Realm of Black Magic” | 32 |

| “Silent and Smooth as a Mirror” | 60 |

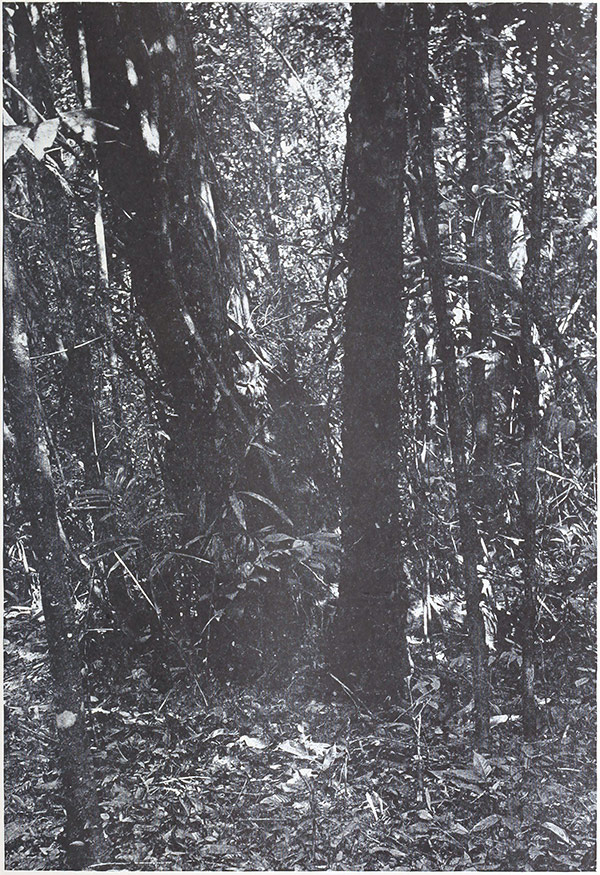

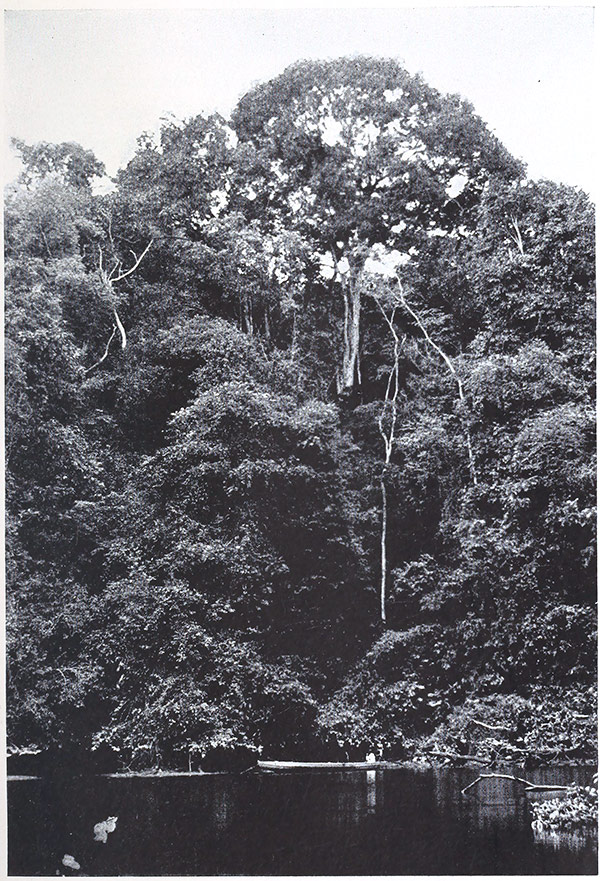

| “The Jungle du Printemps Eternel” | 80 |

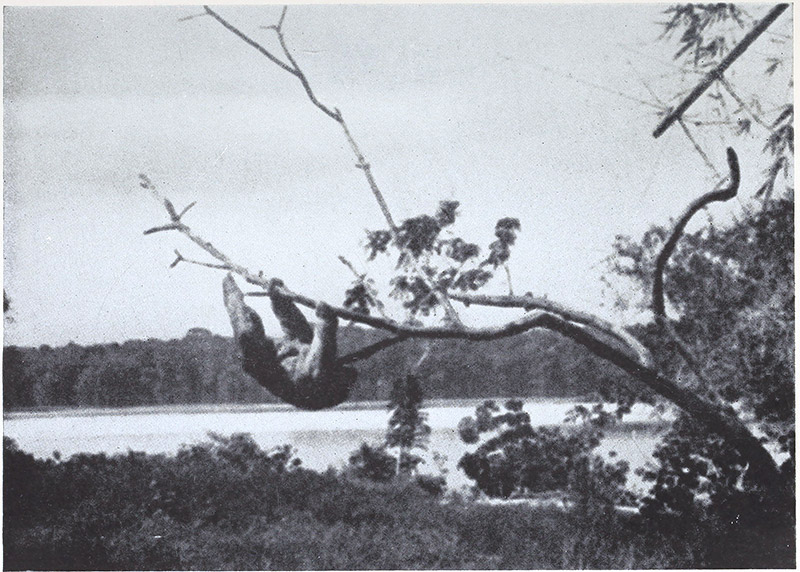

| “A Fitting Inhabitant of Mars” | 100 |

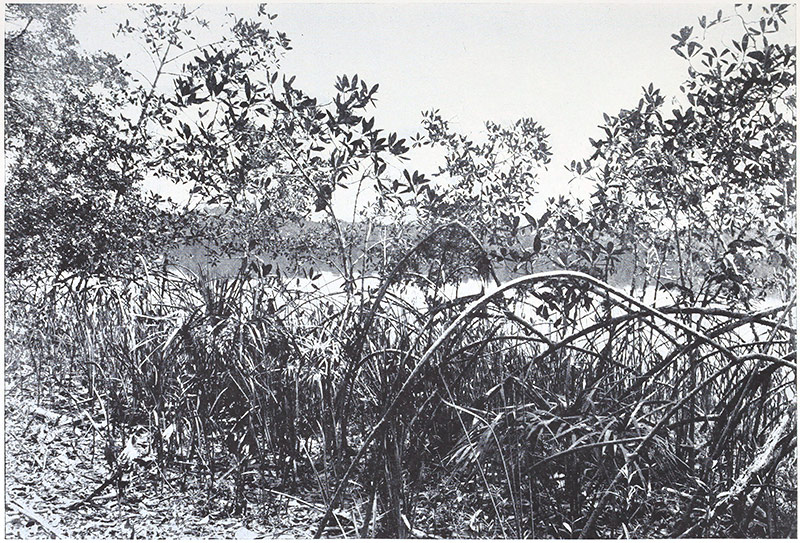

| “In the Sunshine and Warmth of the Mangrove Tangle” | 122 |

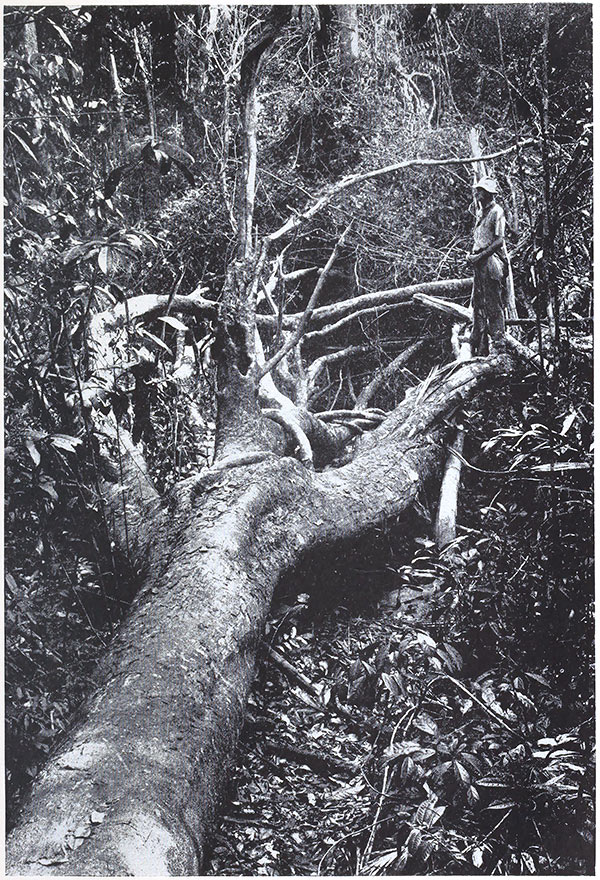

| “The Giant Etaballi Fell Last Night” | 154 |

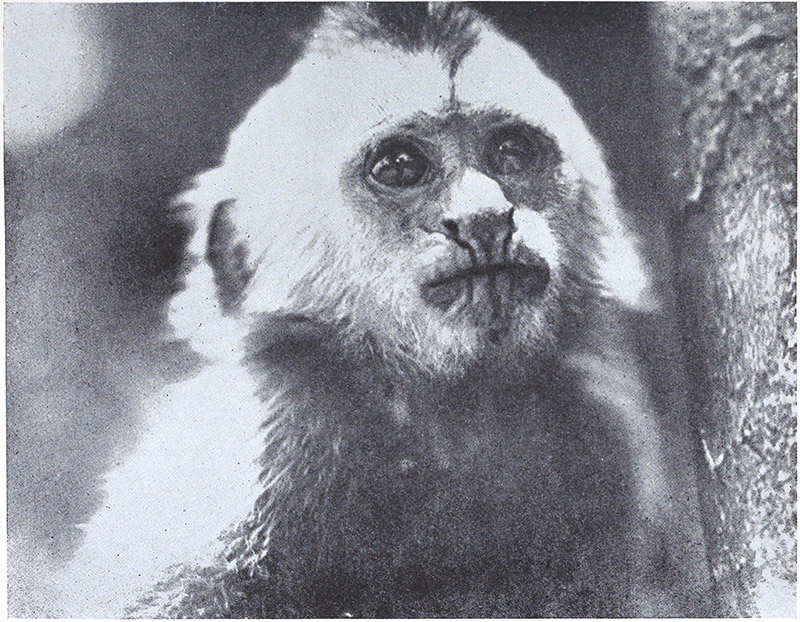

| “One Wistful Little Chap” | 176 |

|

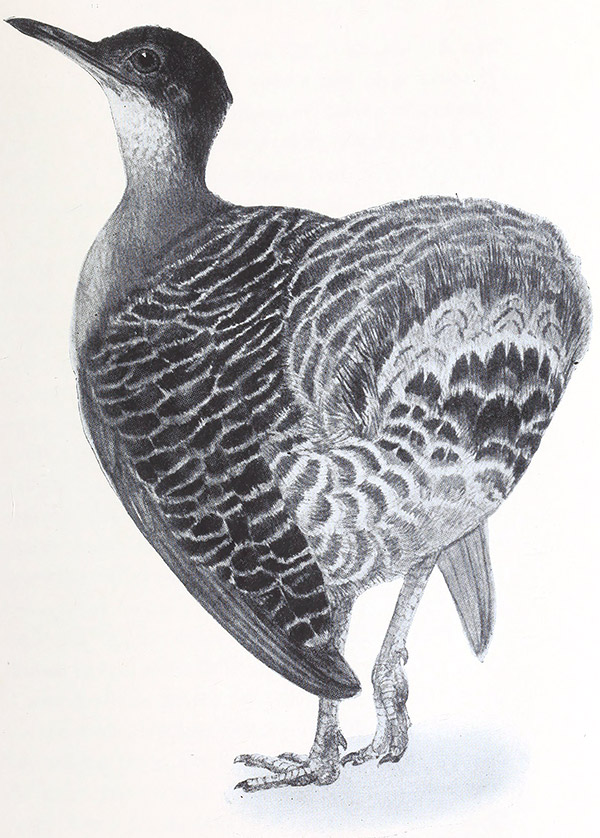

The Tinamou From a painting by Helen Damrosch Tee Van. |

192 |

Jungle Days

This is the story of Opalina

Who lived in the Tad,

Who became the Frog,

Who was eaten by Fish,

Who nourished the Snake,

Who was caught by the Owl,

But fed the Vulture,

Who was shot by Me,

Who wrote this Tale,

Which the Editor took,

And published it Here,

To be read by You,

The last in The Chain,

Of Life in the tropical Jungle.

I offer a living chain of ten links—the first a tiny delicate being, one hundred to the inch, deep in the jungle, with the strangest home in the world—my last, you the present reader of these lines. Between, there befell certain things, of which I attempt falteringly to write. To know and think them is very worth while, to have discovered them is [Pg 4]sheer joy, but to write of them is impertinence, so exciting and unreal are they in reality, and so tame and humdrum are any combinations of our twenty-six letters.

Somewhere today a worm has given up existence, a mouse has been slain, a spider snatched from the web, a jungle bird torn sleeping from its perch; else we should have no song of robin, nor flash of reynard’s red, no humming flight of wasp, nor grace of crouching ocelot. In tropical jungles, in Northern home orchards, anywhere you will, unnumbered activities of bird and beast and insect require daily toll of life.

Now and then we actually witness one of these tragedies or successes—whichever point of view we take—appearing to us as an exciting but isolated event. When once we grasp the idea of chains of life, each of these occurrences assumes a new meaning. Like everything else in the world it is not isolated, but closely linked with other similar happenings. I have sometimes traced even closed chains, one of the shortest of which consisted of predacious flycatchers which fed upon young lizards of a species which, when it grew up, climbed trees and devoured the nestling flycatchers!

One of the most wonderful zoological “Houses that Jack built,” was this of Opalina’s, a long, [Pg 5]swinging, exciting chain, including in its links a Protozoan, two stages of Amphibians, a Fish, a Reptile, two Birds and (unless some intervening act of legislature bars the fact as immoral and illegal) three Mammals,—myself, the Editor, and You.

As I do not want to make it into a mere imaginary animal story, however probable, I will begin, like Dickens, in the middle. I can cope, however lamely, with the entrance and participation of the earlier links, but am wholly out of my depth from the time when I mail my tale. The Akawai Indian who took it upon its first lap toward the Editor should by rights have a place in the chain, especially when I think how much better he might tell of the interrelationships of the various links than can I. Still, I know the shape of the owl’s wings when it dropped upon the snake, but I do not know why the Editor accepted this; I can imitate the death scream of the frog when the fish seized it, but I have no idea why You purchased this volume nor whether you perceive in my tale the huge bed of ignorance in which I have planted this scanty crop of facts. Nor do I know the future of this book, whether it will go to the garret, to be ferreted out in future years by other links, as I used to do, or whether it will find its way to mid-Asia or the [Pg 6]Malay States, or, as I once saw a magazine, half buried, like the pyramids, in Saharan sands, where it had slipped from the camel load of some unknown traveller.

I left my Kartabo laboratory one morning with my gun, headed for the old Dutch stelling. Happening to glance up I saw a mote, lit with the oblique rays of the morning sun. The mote drifted about in circles, which became spirals; the mote became a dot, then a spot, then an oblong, and down the heavens from unknown heights, with the whole of British Guiana spread out beneath him from which to choose, swept a vulture into my very path. We had a quintet, a small flock of our own vultures who came sifting down the sky, day after day, to the feasts of monkey bodies and wild peccaries which we spread for them. I knew all these by sight, from one peculiarity or another, for I was accustomed to watch them hour after hour, striving to learn something of that wonderful soaring, of which all my many hours of flying had taught me nothing.

This bird was a stranger, perhaps from the coast or the inland savannas, for to these birds great spaces are only matters of brief moments. I wanted a yellow-headed vulture, both for the painting of its marvellous head colors, and for the [Pg 7]strange, intensely interesting, one-sided, down-at-the-heel syrinx, which, with the voice, had dissolved long ages ago, leaving only a whistling breath, and an irregular complex of bones straggling over the windpipe. Some day I shall dilate upon vultures as pets—being surpassed in cleanliness, affectionateness and tameness only by baby bears, sloths and certain monkeys.

But today I wanted the newcomer as a specimen. I was surprised to see that he did not head for the regular vulture table, but slid along a slant of the east wind, banked around its side, spreading and curling upward his wing-finger-tips and finally resting against its front edge. Down this he sank slowly, balancing with the grace of perfect mastery, and again swung round and settled suddenly down shore, beyond a web of mangrove roots. This took me by surprise, and I changed my route and pushed through the undergrowth of young palms. Before I came within sight, the bird heard me, rose with a whipping of great pinions and swept around three-fourths of a circle before I could catch enough of a glimpse to drop him. The impetus carried him on and completed the circle, and when I came out on the Cuyuni shore I saw him spread out on what must have been the exact spot from which he had risen.

[Pg 8]

I walked along a greenheart log with little crabs scuttling off on each side, and as I looked ahead at the vulture I saw to my great surprise that it had more colors than any yellow-headed vulture should have, and its plumage was somehow very different. This excited me so that I promptly slipped off the log and joined the crabs in the mud. Paying more attention to my steps I did not again look up until I had reached the tuft of low reeds on which the bird lay. Now at last I understood why my bird had metamorphosed in death, and also why it had chosen to descend to this spot. Instead of one bird, there were two and a reptile. Another tragedy had taken place a few hours earlier, before dawn, a double death, and the sight of these three creatures brought to mind at once the chain for which I am always on the lookout. I picked up my chain by the middle and began searching both ways for the missing links.

The vulture lay with magnificent wings outspread, partly covering a big, spectacled owl, whose dishevelled plumage was in turn wrapped about by several coils of a moderate-sized anaconda. Here was an excellent beginning for my chain, and at once I visualized myself and the snake, although alternate links, yet coupled in contradistinction to my editor and the vulture, the first two [Pg 9]having entered the chain by means of death, whereas the vulture had simply joined in the pacifistic manner of its kind, and as my editor has dealt gently with me heretofore, I allowed myself to believe that his entrance might also be through no more rough handling than a blue slip.

The head of the vulture was already losing some of its brilliant chrome and saffron, so I took it up, noted the conditions of the surrounding sandy mud, and gathered together my spoils. I would have passed within a few feet of the owl and the snake and never discovered them, so close were they in color to the dark reddish beach, yet the vulture with its small eyes and minute nerves had detected this tragedy when still perhaps a mile high in the air, or half a mile up river. There could have been no odor, nor has the bird any adequate nostrils to detect it, had there been one. It was sheer keenness of vision. I looked at the bird’s claws and their weakness showed the necessity of the eternal search for carrion or recently killed creatures. Here in a half minute, it had devoured an eye of the owl and both of those of the serpent. It is a curious thing, this predilection for eyes; give a monkey a fish, and the eyes are the first titbits taken.

Through the vulture I come to the owl link, a [Pg 10]splendid bird clad in the colors of its time of hunting; a great, soft, dark, shadow of a bird, with tiny body and long fluffy plumage of twilight buff and ebony night, lit by twin, orange moons of eyes. The name “spectacled owl” is really more applicable to the downy nestling which is like a white powder puff with two dark feathery spectacles around the eyes. Its name is one of those which I am fond of repeating rapidly—Pulsatrix perspicillata perspicillata. Etymologies do not grow in the jungle and my memory is noted only for its consistent vagueness, but if the owl’s title does not mean The Eye-browed One Who Strikes, it ought to, especially as the subspecific trinomial grants it two eye-brows.

I would give much to know just what the beginning of the combat was like. The middle I could reconstruct without question, and the end was only too apparent. By a most singular coincidence, a few years before, and less than three miles away, I had found the desiccated remains of another spectacled owl mingled with the bones of a snake, only in that instance, the fangs indicated a small fer-de-lance, the owl having succumbed to its venom. This time the owl had rashly attacked a serpent far too heavy for it to lift, or even, as it turned out, successfully to battle with. The mud [Pg 11]had been churned up for a foot in all directions, and the bird’s plumage showed that it must have rolled over and over. The anaconda, having just fed, had come out of the water and was probably stretched out on the sand and mud, as I have seen them, both by full sun and in the moonlight. These owls are birds rather of the creeks and river banks than of the deep jungle, and in their food I have found shrimps, crabs, fish and young birds. Once a few snake vertebræ showed that these reptiles are occasionally killed and devoured.

Whatever possessed the bird to strike its talons deep into the neck and back of this anaconda, none but the owl could say, but from then on the story was written by the combatants and their environment. The snake, like a flash, threw two coils around bird, wings and all, and clamped these tight with a cross vise of muscle. The tighter the coils compressed the deeper the talons of the bird were driven in, but the damage was done with the first strike, and if owl and snake had parted at this moment, neither could have survived. It was a swift, terrible and short fight. The snake could not use its teeth and the bird had no time to bring its beak into play, and there in the night, with the lapping waves of the falling tide only two or three feet away, the two creatures of prey met and fought [Pg 12]and died, in darkness and silence, locked fast together.

A few nights before I had heard, on the opposite side of the bungalow, the deep, sonorous cry of the spectacled owl; within the week I had passed the line-and-crescents track of anacondas, one about the size of this snake and another much larger. And now fate had linked their lives, or rather deaths, with my life, using as her divining rod, the focussing of a sky-soaring vulture.

The owl had not fed that evening, although the bird was so well nourished that it could never have been driven to its foolhardy feat by stress of hunger. Hopeful of lengthening the chain, I rejoiced to see a suspicious swelling about the middle of the snake, which dissection resolved into a good-sized fish—itself carnivorous, locally called a basha. This was the first time I had known one of these fish to fall a victim to a land creature, except in the case of a big kingfisher who had caught two small ones. Like the owl and anaconda, bashas are nocturnal in their activities, and, according to their size, feed on small shrimps, big shrimps, and so on up to six or eight inch catfish. They are built on swift, torpedo-like lines, and clad in iridescent silver mail.

From what I have seen of the habits of anacondas, [Pg 13]I should say that this one had left its hole high up among the upper beach roots late in the night, and softly wound its way down into the rising tide. Here after drinking, the snake sometimes pursues and catches small fish and frogs, but the usual method is to coil up beside a half-buried stick or log and await the tide and the manna it brings. In the van of the waters comes a host of small fry, followed by their pursuers or by larger vegetable feeders, and the serpent has but to choose. In this mangrove lagoon then, there must have been a swirl and a splash, a passive holding fast by the snake for a while until the right opportunity offered, and then a swift throw of coils. There must then be no mistake as to orientation of the fish. It would be a fatal error to attempt the tail first, with scales on end and serried spines to pierce the thickest tissues. It is beyond my knowledge how one of these fish can be swallowed even head first without serious laceration. But here was optical proof of its possibility, a newly swallowed basha, so recently caught that he appeared as in life, with even the delicate turquoise pigment beneath his scales, acting on his silvery armor as quicksilver under glass. The tooth marks of the snake were still clearly visible on the scales,—another link, going steadily down the classes of [Pg 14]vertebrates, mammal, bird, reptile and fish, and still my magic boxes were unexhausted.

Excitedly I cut open the fish. An organism more unlike that of the snake would be hard to imagine. There I had followed an elongated stomach, and had left unexplored many feet of alimentary canal. Here, the fish had his heart literally in his mouth, while his liver and lights were only a very short distance behind, followed by a great expanse of tail to wag him at its will, and drive him through the water with the speed of twin propellers. His eyes are wonderful for night hunting, large, wide, and bent in the middle so he can see both above and on each side. But all this wide-angled vision availed nothing against the lidless, motionless watch of the ambushed anaconda. Searching the crevices of the rocks and logs for timorous small fry, the basha had sculled too close, and the jaws which closed upon him were backed by too much muscle, and too perfect a throttling machine to allow of the least chance of escape. It was a big basha compared with the moderate-sized snake but the fierce eyes had judged well, as the evidence before me proved.

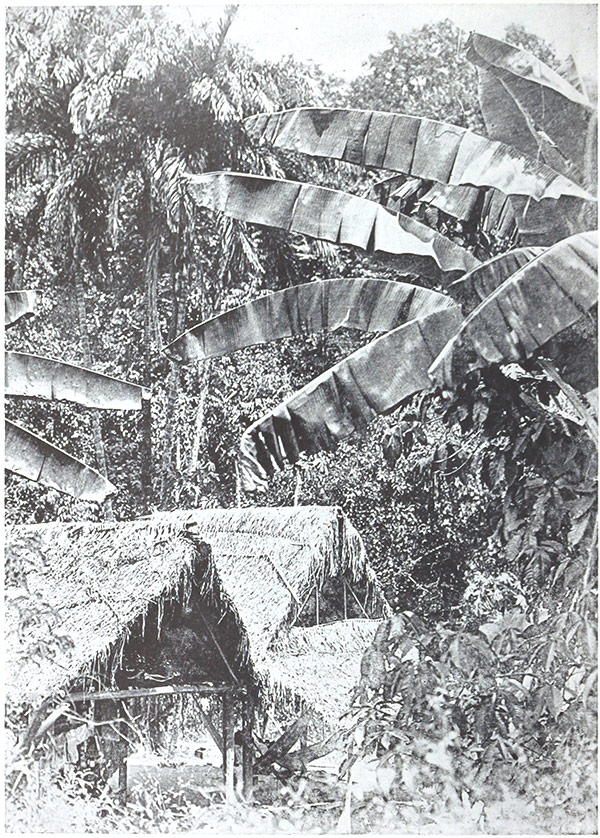

“And there was a Grandmother Frog”

Still my chain held true, and in the stomach of the basha I found what I wanted—another link, and more than I could have hoped for—a representative [Pg 15]of the fifth and last class of vertebrate animals living on the earth, an Amphibian, an enormous frog. This too had been a swift-forged link, so recent that digestion had only affected the head of the creature. I drew it out, set it upon its great squat legs, and there was a grandmother frog almost as in life, a Pok-poke as the Indians call it, or, as a herpetologist would prefer, Leptodactylus caliginosus,—the Smoky Jungle Frog.

She lived in the jungle just behind, where she and a sister of hers had their curious nests of foam, which they guarded from danger, while the tadpoles grew and squirmed within its sudsy mesh as if there were no water in the world. I had watched one of the two, perhaps this one, for hours, and I saw her dart angrily after little fish which came too near. Then, this night, the high full-moon tides had swept over the barrier back of the mangrove roots and set the tadpoles free, and the mother frogs were at liberty to go where they pleased.

From my cot in the bungalow to the south, I had heard in the early part of the night, the death scream of a frog, and it must have been at that moment that somehow the basha had caught the great amphibian. This frog is one of the fiercest of its class, and captures mice, reptiles and small fish without trouble. It is even cannibalistic on [Pg 16]very slight provocation, and two of equal size will sometimes endeavor to swallow one another in the most appallingly matter-of-fact manner.

They represent the opposite extreme in temperament from the pleasantly philosophical giant toads. In outward appearance in the dim light of dusk, the two groups are not unlike, but the moment they are taken in the hand all doubt ceases. After one dive for freedom the toad resigns himself to fate, only venting his spleen in much puffing out of his sides, while the frog either fights until exhausted, or pretends death until opportunity offers for a last mad dash.

In this case the frog must have leaped into the deep water beyond the usual barrier and while swimming been attacked by the equally voracious fish. In addition to the regular croak of this species, it has a most unexpected and unamphibian yell or scream, given only when it thinks itself at the last extremity. It is most unnerving when the frog, held firmly by the hind legs, suddenly puts its whole soul into an ear-splitting peent! peent! peent! peent! peent!

Many a time they are probably saved from death by this cry which startles like a sudden blow, but tonight no utterance in the world could have saved it; its assailant was dumb and all but deaf to [Pg 17]aerial sounds. Its cries were smothered in the water as the fish dived and nuzzled it about the roots, as bashas do with their food,—and it became another link in the chain.

Like a miser with one unfilled coffer, or a gambler with an unfilled royal flush, I went eagerly at the frog with forceps and scalpel. But beyond a meagre residuum of eggs, there was nothing but shrunken organs in its body. The rashness of its venture into river water was perhaps prompted by hunger after its long maternal fast while it watched over its egg-filled nest of foam.

Hopeful to the last, I scrape some mucus from its food canal, place it in a drop of water under my microscope, and—discover Opalina, my last link, which in the course of its most astonishing life history gives me still another.

To the naked eye there is nothing visible—the water seems clear, but when I enlarge the diameter of magnification I lift the veil on another world, and there swim into view a dozen minute lives, oval little beings covered with curving lines, giving the appearance of wandering finger prints. In some lights these are iridescent and they then will deserve the name of Opalina. As for their personality, they are oval and rather flat, it would take one hundred of them to stretch an inch, they have no mouth, and [Pg 18]they are covered with a fur of flagella with which they whip themselves through the water. Indeed the whole of their little selves consists of a multitude of nuclei, sometimes as many as two hundred, exactly alike,—facial expression, profile, torso, limbs, pose, all are summed up in rounded nuclei, partly obscured by a mist of vibrating flagella.

As for their gait, they move along with colorful waves, steadily and gently, not keeping an absolutely straight course and making rather much leeway, as any rounded, keelless craft, surrounded with its own paddle-wheels, must expect to do.

I have placed Opalina under very strange and unpleasant conditions in thus subjecting it to the inhospitable qualities of a drop of clear water. Even as I watch, it begins to slow down, and the flagella move less rapidly and evenly. It prefers an environment far different, where I discovered it living happily and contentedly in the stomach and intestines of a frog, where its iridescence was lost, or rather had never existed in the absolute darkness; where its delicate hairs must often be unmercifully crushed and bent in the ever-moving tube, and where air and sky, trees and sun, sound and color were forever unknown; in their place only bits of half-digested ants and beetles, thousand-legs and worms, rolled and tumbled along in [Pg 19]the dense gastric stream of acid pepsin; a strange choice of home for one of our fellow living beings on the earth.

After an Opalina has flagellated itself about, and fed for a time in its strange, almost crystalline way on the juices of its host’s food, its body begins to contract, and narrows across the center until it looks somewhat like a map of the New World. Finally its isthmus thread breaks and two Opalinas swim placidly off, both identical, except that they have half the number of nuclei as before. We cannot wonder that there is no backward glance, or wave of cilia, or even memory of their other body, for they are themselves, or rather it is they, or it is each: our whole vocabulary, our entire stock of pronouns breaks down, our very conception of individuality is shattered by the life of Opalina.

Each daughter cell or self-twin, or whatever we choose to conceive it, divides in turn. Finally there comes a day (or rather some Einstein period of space-time, for there are no days in a frog’s stomach!) when Opalina’s fraction has reached a stage with only two nuclei. When this has creased and stretched, and finally broken like two bits of drawn-out molasses candy, we have the last divisional possibility. The time for the great adventure [Pg 20]has arrived, with decks cleared for action, or, as a protozoölogist would put it, with the flagellate’s protoplasm uni-nucleate, approximating encystment.

The encysting process is but slightly understood, but the tiny one-two-hundredth-of-its-former-self—Opalina curls up, its paddle-wheels run down, it forms a shell, and rolls into the current which it has withstood for a Protozoan’s lifetime. Out into the world drifts the minute ball of latent life, a plaything of the cosmos, permitted neither to see, hear, eat, nor to move of its own volition. It hopes (only it cannot even desire) to find itself in water, it must fall or be washed into a pool with tadpoles, one of which must come along at the right moment and swallow it with the débris upon which it rests. The possibility of this elaborate concatenation of events has everything against it, and yet it must occur or death will result. No wonder that the population of Opalinas does not overstock its limited and retired environment!

Supposing that all happens as it should, and that the only chance in a hundred thousand comes to pass, the encysted being knows or is affected in some mysterious way by entrance into the body of the tadpole. The cyst is dissolved and the infant Opalina begins to feed and to develop new nuclei. [Pg 21]Like the queen ant after she has been walled forever into her chamber, the life of the little Onecell would seem to be extremely sedentary and humdrum, in fact monotonous, until its turn comes to fractionize itself, and again severally to go into the outside world, multiplied and by installments. But as the queen ant had her one superlative day of sunlight, heavenly flight and a mate, so Opalina, while she is still wholly herself, has a little adventure all her own.

Let us strive to visualize her environment as it would appear to her if she could find time and ability, with her single cell, to do more than feed and bisect herself. Once free from her horny cyst she stretches her drop of a body, sets all her paddle-hairs in motion and swims slowly off. If we suppose that she has been swallowed by a tadpole an inch long, her living quarters are astonishingly spacious or rather elongated. Passing from end to end she would find a living tube two feet in length, a dizzy path to traverse, as it is curled in a tight, many-whorled spiral,—the stairway, the domicile, the universe at present for Opalina. She is compelled to be a vegetarian, for nothing but masses of decayed leaf tissue and black mud and algæ come down the stairway. For many days there is only the sound of water gurgling past the [Pg 22]tadpole’s gills, or glimpses of sticks and leaves and the occasional flash of a small fish through the thin skin periscope of its body.

Then the tadpole’s mumbling even of half-rotted leaves comes to an end, and both it and its guests begin to fast. Down the whorls comes less and less of vegetable detritus, and Opalina must feel like the crew of a submarine when the food supply runs short. At the same time something very strange happens, the experience of which eludes our utmost imagination. Poe wrote a memorable tale of a prison cell which day by day grew smaller, and Opalina goes through much the same adventure. If she frequently traverses her tube, she finds it growing shorter and shorter. As it contracts, the spiral untwists and straightens out, while all the time the rations are cut off. A dark curtain of pigment is drawn across the epidermal periscope and as books of dire adventure say, the ‘horror of darkness is added to the terrible mental uncertainty.’ The whole movement of the organism changes; there is no longer the rush and swish of water, and the even, undulatory motion alters to a series of spasmodic jerks,—quite the opposite of ordinary transition from water to land. Instead of water rushing through the gills of her host, Opalina might now hear strange musical sounds, [Pg 23]loud and low, the singing of insects, the soughing of swamp palms.

Opalina about this time, should be feeling very low in her mind from lack of food, and the uncertainty of explanation of why the larger her host grew, the smaller, more confined became her quarters. The tension is relieved at last by a new influx of provender, but no more inert mold or disintegrated leaves. Down the short, straight tube appears a live millipede, kicking as only a millipede can, with its thousand heels. Deserting for a moment Opalina’s point of view, my scientific conscience insists on asserting itself to the effect that no millipede with which I am acquainted has even half a thousand legs. But not to quibble over details, even a few hundred kicking legs must make quite a commotion in Opalina’s home, before the pepsin puts a quietus on the unwilling invader.

From now on there is no lack of food, for at each sudden jerk of the whole amphibian there comes down some animal or other. The vegetarian tadpole with its enormously lengthened digestive apparatus, has crawled out on land, fasting while the miracle is being wrought with its plumbing, and when the readjustment is made to more easily assimilated animal food, and it has become a frog, it forgets all about leaves and algæ, and leaps after [Pg 24]and captures almost any living creature which crosses its path and which is small enough to be engulfed.

With the refurnishing of her apartment and the sudden and complete change of diet, the exigencies of life are past for Opalina. She has now but to move blindly about, bathed in a stream of nutriment, and from time to time, nonchalantly to cut herself in twain. Only one other possibility awaits, that which occurred in the case of our Opalina. There comes a time when the sudden leap is not followed by an inrush of food, but by another leap and still another and finally a headlong dive, a splash and a rush of water, which, were protozoans given to reincarnated memory, might recall times long past. Suddenly came a violent spasm, then a terrible struggle, ending in a strange quiet: Opalina has become a link.

All motion is at an end, and instead of food comes compression, closer and closer shut the walls and soon they break down and a new fluid pours in. Opalina’s cyst had dissolved readily in the tadpole’s stomach, but her own body was able to withstand what all the food of tadpole and frog could not. If I had not wanted the painting of a vulture’s head, little Opalina, together with the body of her life-long host, would have corroded and [Pg 25]melted, and in the dark depths of the tropical waters her multitude of paddle-hairs, her more or fewer nuclei, all would have dissolved and been re-absorbed, to furnish their iota of energy to the swift silvery fish.

This flimsy little, sky-scraper castle of Jack’s, built of isolated bricks of facts, gives a hint of the wonderland of correlation. Facts are necessary, but even a pack-rat can assemble a gallon of beans in a single night. To link facts together, to see them forming into a concrete whole; to make A fit into ARCH and ARCH into ARCHITECTURE, that is one great joy of life which, of all the links in my chain, only the Editor, You and I—the Mammals—can know.

[Pg 26]

Many, many, many years ago, in some distant place, among trees or rocks, perhaps on the banks of a river, certainly in the warm light of the sun, one of your ancestors and mine became tired of squatting on a branch or on the ground, and sat himself—or herself—on a fallen log. If it was himself then he must soon have felt the need of a lap on which to rest things—his hands if nothing else. And from that day to this, his male descendants still feel that lack down to the last unfortunate who is handed a cup of tea or a three-legged egg-shell of cocoa, a serviette and a cake with no support other than wholly inadequate knees.

Of the first table I can relate nothing with certainty, but of the last I could gossip endlessly, limited only by writer’s cramp and my supply of adjectives. For I am at this moment sitting at the last table ever made—last because it is not quite finished. I am forever tacking on a little shelf or an annex at one side, and so I feel a right to place it at the opposite end of our distant forebear’s piece [Pg 27]of bark or stiff frond or whatever it was that he balanced on his hairy, bowed knees. And yet his table and mine are much more alike than the mahogany roll-top with swinging telephone and octave of assistants’ push buttons to which our more sophisticated but less happy bank presidents sit down.

That reminds me, however, that my laboratory table is also of mahogany, because here in the jungle of British Guiana it is the cheapest material in the form of boards.

The crab-wood top grew in this very jungle, its first, rich red-brown cells fashioned from the water and earth and sun at least a century and a half ago. It is possible to detect the double character of the rings, indicating the two annual rainy seasons—the two springs which quickened the sap and leafage, and the two periods of drought when the life of the tree slowed down. Close to the heart of the great board is a strange ring, or rather node between rings—a wide, even space, which my reckoning places about 1776; about the time when our fore-fathers were fighting for freedom, whose memory we cannot toast even in wine; they had just penned a Declaration of Independence, whereas we are considering passing a law to keep monkeys in their proper place. I pause in my table talk long enough [Pg 28]to thank heaven that we are still allowed to believe in the rotundity of the earth, that the Indians’ gift of tobacco is still permitted us, and that tea is not yet thrown overboard!

The year 1776 at Kartabo was one of almost continual rain,—so much my broad, crab-wood space shows—with no slack-growth period for this slender sapling. And imagination helps us still farther when we recall something of the human history of the place. Ever since 1600 the Dutch had strived to make this region habitable. The little fort, on the island off shore had barely pointed its guns down river, had fired its well-weathered cannon in victory, and had silenced them in defeat to English and French privateers (often an old-fashioned way of pronouncing pirate!). Hundreds of Indian slaves had worked on the four large plantations and only in 1772 had the settlers admitted that this region was fit only for jungle, wild animals, and future enthusiastic scientists with tables. And now I realized that my table-top had sprouted in the very year that the Dutch left for the coast—one of the first wild things to spring up in their retreating footsteps, a pioneer in again “letting in the jungle.”

The magic of my jungle table is always apparent in one way or another. No thoughts which it generates, [Pg 29]nor happenings on its surface are aught but vivid, vital, memorable: It is an event to hurry out to in early morning, it is a regret to leave for jungle tramps and for meals, it is only exhaustion which excuses its midnight abandonment. A magic carpet transports one’s body from place to place, whereas my table impels mental gamuts from quiet meditation to dire tragedy, from righteous anger, to wonder at the marvellous sights it vouchsafes me, and despair at thought of their interpretation. Only once have I ever become impatient with my artificial lap, when an injury to my foot compelled me to remain indoors for a time. Then indeed the jungle called and les affaires de ma table palled,—a commentary on my lack of philosophy.

The first magic which my table made was to prove to be alive. The top was undeniably dead, well seasoned and inert, but my black boy Sam had cut the legs from jungle saplings. I put my hand down one day and felt a soft tissue something, half way to the floor. It seemed a moth’s wings or a tangle of dense cobwebs, but to my surprise I saw that my table was sprouting leaves, rather pale and dwarfed, limp and flabby, to be sure, but of rapid growth, and besides there were four other buds just started. I had put cans of water on the floor beneath the legs to discourage ants, and the sap of [Pg 30]the new-cut poles had greedily sucked this up, and even in the dimness of the laboratory light had begun to spread into foliage. It was proving a real jungle table and I was rather thrilled to see that the warfare of the wilderness had already begun at arm’s reach,—a tiny caterpillar had crawled from somewhere to the new blown leaves and had eaten out a bit. I pictured my table as sprouting, growing higher and higher, until, in lieu of Alice’s toadstool, I cut jungle saplings for my chair legs too, and mounted with the table! The Indian summer of my table legs soon passed however, the sap dried, the leaves wilted, and from saplings they became furniture.

But the magic continued. If the crab-wood boards of the top were not quickened into even passing vitality, they could do equally surprising things, the first of which was to become vocal. Day after day there arose a low grating throb, lasting for a few seconds, and sometimes increasing in rapidity and pitch until it assumed a true musical quality. Its direction eluded me until I happened to have my ear close to the table, when the vibrations seemed to sound at my very ear-drum. Then one day I noticed a tiny pile of sawdust on the floor and traced it to a rounded hole from which at intervals came the sound. For three months my [Pg 31]musical table continued its monotone, day and night, until in the quiet of midnight it became part of the silence, and I was aware of it only with effort. Then it ceased, and its cessation held my attention more than its occurrence had done.

Months later when the last of my small table furnishings had been packed, I tipped up the table to carry it away, and there in the hole from which the monotone and the sawdust had flowed there hung suspended a gorgeous, mummified beetle, its long antennæ of salmon and black curved up and over its back, while its fluted cuirass shone through dust and dim light, deep forest green framed with a delicate border of primuline yellow. My table top had furnished nourishment, sanctuary, sounding board, through all the long period of immaturity, but at the climax of this little life, the hardened vegetable fibre had held firm, despite all the efforts of the green beetle, and cruelly withheld freedom by some slight, needless entanglement of its hind legs. So passed two tragedies of my table,—the first vegetable, the second animal.

Usually my table is littered with beautiful mysterious things which, to a casual onlooker, could have absolutely no meaning. There is a small, exquisitely molded bony cup or vase, partly covered at the top, and with a long, daintily curved [Pg 32]handle, which I keep suspended as a receptacle for pins. It might well be a delicate netsuke carved in pre-democratic Japan by some craftsman who wrought for love; it might be almost anything but a music-box. And now my reverie was interrupted by a sound from the neighboring jungle,—a sound common but never old. As the bony box might have been far other than it was, so the deep vibrations could well be elemental,—a distant wind, sinister as if it came straight from blowing across terrible fields after battle, or through cities wracked with pestilence; the eaves around which it had howled must have been very evil, roofing ancient castles which sheltered thoughts of treachery and deeds of unfair violence. But I knew that the rich primeval resonances came echoing from bog bony boxes exactly like my pin holder, in the throats of a tree-top circle of beings like aged, thick-necked dwarfs squatting high on swaying branches, looking out toward me over the expanse of quicksilver water. At the climax, when it seemed impossible that any one animal could produce such an appalling volume of sound, a blur swiftly feathered the surface of the river, as if the impinging ululations of monkey voices had actually been translated into visibility—as liquid in a glass is troubled in sympathy with certain chords of music. My ear [Pg 33]changed focus, and like a search-light shifting from distant cloud to airplane, attended a sound at my very elbow, throbbing, muffled—and again my table sang.

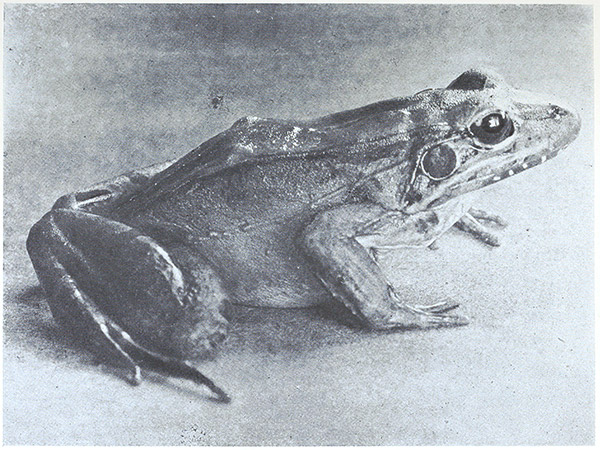

“Well within the realm of black magic”

Amazing things, things apparently well within the realm of black magic occur and recur on my table. Late this evening a windless tropical rain fell so evenly and steadily that the monotone on the bamboos seemed intended for some other sense than the ear. I sat describing the delicate arrangement of the tiny bones and muscles of the syrinx of a flycatcher, striving to understand how there could emanate from this instrument such an intricate vocabulary of screams and whistles, trills and octaves as this bird and its fellows uttered every day in the laboratory compound.

Suddenly something flew swiftly past my face and alighted clumsily among my vials and instruments. I saw a giant wood roach all browns and greys, with marbled wings, strange as to pigment and size, but with the unmistakable head and poise and personality of a New York “Archie.” The insect had flown through the rain and into the window, but a glance showed that it was in dire extremity, being in the grasp of a two-inch ctenid spider. The eight long legs held firmly, but had not been able to prevent the roach from flying. [Pg 34]At the moment of alighting the arachnid shifted its grip, and secured the wings so that further escape was impossible. Both were desirable specimens and I instantly slipped a deep stender dish over them and again lost myself in my binocular microscope.

Fifteen minutes later I looked up and saw a sight so strange that Sime himself would hesitate to delineate it. The spider still clung tenaciously to its victim, but the wood roach had her revenge. She was barely alive, yet in a quarter of an hour she had changed from a strong, virile creature to an empty husk, dry and hollow, while over her and the spider, over glass and table-top scurried fifty-one active roachlets. They had burst from their mother fully equipped and ready for life, leaving her but a vacant, gaping shell, a maternal film, the ghost of a roach: Tiny, green, transparent, fleet, they raced back and forth over the spider. He grasped in vain at their diminutive forms at the same time still clutching the dying, flavorless shred of a mother roach, holding fast as though he hoped that this unnatural miracle might reverse itself at any moment, and his victim again become fat and toothsome.

I knew that some of the fish swimming in the aquarium near by lay thousands of eggs, and that [Pg 35]other insects leave myriads of offspring, yet this magic of the wood roach, this resolution of one into fifty made wonderfully vivid the reproductive powers of tropical creatures. When in a moment of time, relatively speaking, a single insect can be broken up into half a hundred active, functioning duplicates of herself, the chance for variation, for new adjustments, for survival of the more delicately adapted is faintly understood. Here was spontaneous generation with a vengeance.

To hark back again to sounds and voices; I could fashion a whole essay on the calls and songs and noises which come to me at my table, from river, compound and jungle. On very still days I can hear the giant catfish thrumming deep beneath the water, and the cry of hawk-eagles high in the heavens; at hot, high noon Attila, the brain-fever Cotinga, calls and calls and calls, while through the hush of midnight there comes the hopeless cadence of the poor-me-one; I know from a sudden babel of humming-bird squeaks and frenzied shrieks of flycatchers that a tree snake has been discovered in the bamboos; I am certain without looking that it is very close to five o’clock, when the first old witch cuckoo begins whaleeping on its regular evening excursion for a drink in the river, and so on.

[Pg 36]

Probably by virtue of my table’s magic, I have learned, like Chubu and Sheemish, to work a little miracle all by myself. My principal technical work just now is the study of the syrinx of birds, their remarkable, complex organ of voice placed far down beyond the throat, in the very body itself, and the correlation of its structure with the actual voice of the bird. At present I try to solve some knotty problems of tinamous, strange, bob-tailed game-birds, related both to fowls and to ostriches, which live on the jungle floor, lay eggs like burnished turquoise and age-purpled jade, and call to one another with sweet, liquid whistles. My Indians bring in numbers of these birds for the mess, so I have an abundance of material for study. I try an experiment on my table which has been already successful in other cases. I decapitate a bird before it is plucked for the pot, and holding it firmly on its back, I strike a sharp blow on the muscles of the breast. Nothing results, so I shift position and try again. This time a short, high note is produced. I draw out the neck a little and obtain a lower note, still further and strike a half tone lower in the scale. If I could prolong these I could reconstruct the whole plaintive evening call of the variegated tinamou here on my very table top.

[Pg 37]

Then I take the windpipe and carefully work out the wonderful architecture of the whole organ, the delicate adaptation and adjustment of each part fulfilling its special function, the whole working together as no man-made machine ever could. From throat to syrinx the windpipe extends, composed of thin membranous tissue, kept open by a series of a hundred and twenty-five perfect rings. Here we have assurance of an entrance for air forever clear and open, so mobile that it bends back double, yet with no chance of closure through any contortion of the neck. The throat end is guarded by a slit which opens and closes at the slightest need; the opposite end marks the top of the syrinx and the division into two tubes each leading to a lung. For twenty rings above this point, the windpipe is slightly enlarged and almost solid, forming a bony sounding board which acts, in a less degree, like the throat box of the red howling monkeys; giving resonance and carrying power to the voice.

The syrinx itself is boxed in by four pairs of large rings and semi-rings, which protect two pairs of cartilage pads. The pads of each pair touch one another along their inner sides, and when the windpipe is relaxed the seam between them is closed tight. A slight tug, as in my decapitated bird, corresponding to a raising of the head and neck in [Pg 38]a live individual, and the pads revolve slightly, bringing a constricted part of each into the seam, forming a tiny gap. Through this the air from the lungs and air-sacs rushes and we have the mechanism of the first, high, clear note of the call, a superlatively sweet whistle on middle C, carrying a mile through the thick jungle. Although quite another story, my mind rushes on, away from the technical anatomical problem, to the realization that this sound is a summons from the very advanced female of this species to any unattached male bird, an announcement that she is ready to lay an egg for him, provided he will incubate it, hatch it and assume entire charge of the young bird. And I do not know whether to cheer or blush for my sex when I state that the woods hereabouts are full of amiable, domestically inclined males who are eager and willing to agree to this rather one-sided contract. Their syringes are almost identical but the loud evening calls are invariably those of the idler sex. Notes for Women! must have been the slogan of the long since successful tinamou suffragists.

It is amusing to trace a circular gamut of human interest in animal sounds: Listening to various screams, warbles, whistles, roars, chirps, trills and twitters in the jungle, an intelligent interest impels [Pg 39]us to desire to know the author; having accomplished this by patient stalking and watching, and if needs be, shooting, the wish is aroused to discover the accompanying emotion, the incentive, and then the fascinating problem presents itself of the answer, whether in terms of action or vocal, whether filial, amorous, pugnacious, or merely companionable. This is more difficult, but in many cases possible. Almost always this ends the quest, while it is still incomplete. The method, the physical mechanism is after all, the foundation of the phenomenon, and when we have secured a specimen, taken it to our table,—a tinamou in the present instance—then we may produce the call artificially, and by tireless and detailed dissection detect air channel, resonance chamber, syrinx mechanism, vocal chords, controlling muscles, and envy the enormous bodily reservoir of air—lungs, sacs, the very hollow bones themselves. Leaning back and listening to a living, wild tinamou calling in the neighboring forest, feeling rich in the possession of its Who! Why! and How!, we realize the fullest joy of intimacy with the furtive beings of earth, with the elusive small folk of the jungle.

After a long jungle tramp I was leaving Hacka Trail for the Station clearing when I caught sight of a group of small objects on the under side of a [Pg 40]gigantic bromeliad leaf. If the leaf had been fifty feet up they might have been great fruit bats, if twenty feet their size would have equalled that of vampires, but as they were only of arms’ reach above my head they could not be more than an inch in length. When I had hacked off the leaf and dodged its fall, I found nine little chrysalids clustered together, and even on close scrutiny their resemblance to a group of diminutive bats was still absurdly real. This intimate association of chrysalids is a rare thing, as rare as the nocturnal association of butterflies sleeping in jungle glades.

I carried off the leaf curved into a great emerald arch, and fastened it over my table, where it dried into a fluted dome of green tissue. Three days passed with no sign of change from the chrysalids swinging from their silken pendants, when my eye caught a glint of silver far down the under side of this same leaf, near the tip. Another glance made me think them inexplicable dewdrops, a third crystalized them into pearl-like consistency, while a fourth careful scrutiny showed me they were two eggs of a scarlet and black heliconid butterfly, the kind which fluttered fearlessly ahead of me along the jungle paths. Here was a splendid example of oblique discovery, of scientific second sight.

I wondered what sculpture the surface would [Pg 41]show,—these two isolated spheres, shining like the third zodiacal sign against a dark green heaven. At the first look through the microscope I forgot all about surface and possible spines or hexagonal lattice-work; it was the contents which drew and held my attention. A butterfly egg in due course of time should yield a caterpillar, which before it emerges is wound into a curve to fit its minute spherical home. But here was a new cosmos,—a planetful of slowly moving creatures which had nothing in common with a heliconian caterpillar. Slowly they milled around their little world, living, like some Gulliverian organisms, on the inside looking out. The egg was an opalescent sphere, a twelfth of an inch across, and in my microscope field it seemed really suspended in space,—in a dark chlorophyll ether. More than once as my eye tired in watching I seemed to see the whole egg revolving while the inmates remained stationary. Now and then one of the egg-beings turned and went against the current, setting up a traffic whirlpool which caused all to cross and recross in confusion. The film of eggshell was translucent and clear immediately beneath my eye, clouding into exquisite purplish pearl at the periphery. One of the inmates came to rest directly beneath the surface, and I saw it was a tiny grub, legless, searching about blindly, feeling, [Pg 42]sensing, living, after whatsoever manner grubs live who find themselves prisoned in a butterfly egg. The grub hastened on, fell into wriggle with its companions and soon slipped from view below the edge of its world. Doubtless in a few seconds it completed its internal orbit and again crossed my field of view, but like a circulating Roman army on the stage, or the sequence of ideas in some sphere not attached to jungle leaves, all seemed identical. I could never tell when the same one appeared again; indeed while they moved I could make no estimate even of their numbers. I only knew that some minute hymenopteron, doubtless a member of the wonderful tribe of Chalcids, had, a few days before, thrust her ovipositor through this translucent pearl and left within as many eggs as there now were grubs, then flown on to the next egg. I once was fortunate enough to observe this fairy egg-laying,[1] and now I was trembling with excitement at the unexpected treasure trove I had unwittingly brought to my table.

[1] Edge of the Jungle, pp. 38-40.

Closest examination from every side with high power lens revealed to me no hint of the place of entrance. Once when I crawled from the heart of great Cheops out through the robbers’ tunnel, and finally scraped and squeezed through the narrow [Pg 43]crevice through which they had broken in, I thought it small indeed. But here was a phenomenon far more wonderful than a full-rigged ship in a bottle, a snow-storm in a paper weight, or the thieving Arabs’ entrance in the pyramid.

Four days passed, the wonderful globes lay before me, and then I examined them again. A remarkable change had been wrought, a living planet had devolved into a dead satellite; the egg had become a sarcophagus with a dozen mummies. The little cases were arranged around a central core of débris, some standing on end as in the Egyptian room of a museum, a group facing one another as some wordless gossip passed from one sealed mouth to the next. A single mummy doll rested against the opal shell, with eyes pressed close to the translucent pane, eyes which at present existed only in outward form as insensitive tissue. This one individual had chosen for his final pupal change a position at the very outer rim, where the first nerve tingles of sight would reflect the mysteries of the world beyond that sphere of food and fellows which had heretofore bounded his existence; my pronouns masculine are merely adumbrative.

So passed a week with the little silent mummies still unchanged; seven days,—sufficient time, Biblically speaking, for the creation of the world. [Pg 44]But just as all the glorious truth and beauty of evolution is concealed within the metaphor of Genesis, so, hidden from our groping senses, miracles of change were being wrought within the butterfly’s egg. The following morning the spell had broken, and the sphere again seethed with life, resurrected, reincarnated. On the central compost heap were piled twelve suits of second-hand pupal skins, tissue paper cartoons of their wearers, glimmering weirdly through the shell. The tiny wasps had all emerged and were active, and already there was a hole bitten through, with small ships of splintered opal scattered outside. As I watched, a wasp midget shoved aside a group of idlers, pushed his way to the door and began to gnaw with all his might. His great bulging scarlet eyes blocked the way as he tried time after time to press through. The whole eggful knew that something of great import was happening, and the outside air must have carried exciting tidings, for all moved about as quickly as their crowded quarters permitted. Twice the Gnawer left his labors and walked about nervously, once making the entire circuit of the egg. His leadership, his pioneer daring was marked not only by action; I found that I could readily distinguish him from the others. He was a shade smaller, his lines were trimmer, and [Pg 45]upon his back was a round insignium of gold which the others lacked.

Several others came to the opening, tried to pass and turned aside—none made attempt to aid in the escape from prison. Back came the ambitious one and fell to with all his strength. He lacked leverage, and only when three of his companions came up at once, was he able, by pressing his hind legs against their faces and bodies, to break off an unusually large bit of the horny shell. This made a splendid gap, and after two smaller bits had been chewed off, the little insect wriggled through the jagged hole, and stood upon the summit of his world. Tiny though he was, needing thirty-five of him to cover an inch of space, his coloring was exquisite; eyes dull scarlet, sparsely covered with golden hair, body armor of glistening black from head to tip of abdomen, with badge of yellow gold shining from between his wings. These wings were small, paddle-shaped and almost free of veining, while the scales on their surface glowed with iridescent play of lilac, yellow and pale green.

Now ensued an elaborate cleaning of every part of his body, and then he ran off at top speed. Several quick turns near-by on the leaf and back he came, gave a final wipe to his forelegs, climbed up, antennæd the hole and took his stand a wasp’s [Pg 46]length away. This action came as a complete surprise; I never expected him to return after such a laborious escape.

Soon a second wasp came to the breach and squeezed through. Hardly had its combing and scraping been completed when, to my astonishment, the Gnawer rushed forward, roughly seized the second wasp and began to bang its head most unmercifully. At every push, the head of the unfortunate insect wobbled as if about to fall off. Suddenly it rose to its feet and the first wasp mated with it. I then realized that instead of assault and battery, this was courtship, that in place of horrible fratricide, this was the nuptials of brother and sister. The mating lasted but a second, when the first wasp returned to its watchful waiting, and the other spun its paddle-shaped wings and flew off as far as the confines of the covered glass dish permitted. I never took my eye from the lens as the miracle continued. One after another the sister wasps emerged, to the number of eleven, and in each case the male enacted his rough courtship and mated for not longer than two seconds. In each case, without a moment’s hesitation, the female flew swiftly away. Once, when three emerged quickly one after the other, they did not leave the egg but waited quietly for the male.

[Pg 47]

The whole thing began and ended so quickly that it was some time before I could review the whole wonderful performance from the conjectured laying of the eggs, through the grub, pupa and now the adult stage. I looked again at these midgets, only a thirty-fifth of an inch in length, and considered their necessities in life,—food, mate and a butterfly’s egg, and I realized the enormous advantage of this simplification of the mating problem. But the most astonishing thing of all was the thought of the anticipation, of the perfect adjustment of sex in the unformed organisms, the pre-natal compulsory affiancing, together with the apparently satisfactory disregard of inbreeding adumbrated in the very eggs themselves of the original mother wasplet.

No matter how imperfectly I have translated this event, disregarding my futile phrases and in spite of my inadequate description, it was a most wonderful happening, which for a time completely eclipsed all other affairs of my table top. In delicate achievement, astounding unexpectancy and magical matter-of-factness, it left the onlooker with a supreme realization of ignorance and a dominant sense of awe.

And so as I sit at my table, my little cosmos of space and time presents deaths by violence, and [Pg 48]lives of quiet, unperturbed peace; acrid, burning odors and smashing, sweeping brilliancy of color; living skin soft and smooth as clay, or fretted like shagreen; voices almost high enough to become visible; comedy so delicate that appreciation never reaches laughter, and tragedy so cruel and needless that it stirs doubts of the very roots of things. All these and many more, begin, occur and pass before me,—things which go to make up a world.

[Pg 49]

A tropical night may be quiet and calm, and yet full of a strange restlessness. It was such a one when I lay in my bathing suit close to the grey granite of Boom-boom Point, and watched the low-hung North Star twinkling through the fretwork of mangrove roots. Three great planets added their separate lustre, Mars overhead in the very heart of Scorpio, Jupiter well down to the west, and Venus just setting, shining with the light of a half moon. It was, however, predominantly, a Night of the Milky Way. The great luminous highway stretched from horizon to horizon, illuminating hundreds of the tiny mica facets in my rocky couch. Great Cygnus climbed slowly, majestically, along the glowing path, and Pegasus reared his head just above the horizon. Has the composite light of these myriad stars the same sinister psychic effect as the moon rays? Else why were I and so many creatures restless? Only the giant tree-frogs, the Maximas, wahrooked in endless, stoical reiteration, unaffected by stars or [Pg 50]planets, as endless as an after-dinner speech and as unintelligible. Now and then a trio of Typhon’s toads exploded in a short, hysterical outburst, as if intercalating Hear! Hear! or Cut it out!—a very impudent, undesirable, nervous protest against the brain-fever repetitions of the great frogs.

I was ready for something unusual, and it came,—merely a sound, but one which will probably be as mysterious on the day of my death as it is now. Without warning through the air overhead, against the translucent celestial glow, came an izzzzzzzz-wonk! wonk! wonk! as evanescent as the low twang of a bullet, wholly indescribable in its true weirdness and richness. No beetle ever turned as quickly as the wonk! wonk! wonk! indicated; no bat ever achieved a twang with its velvet wings. It was no sound of bird or insect that I knew; and it came again and again from the same direction, and seemed to emanate from some creature which watched me. The wonk! wonk! as of sudden, banking flight, happened close in front, over the water. I flashed my electric torch and saw nothing, although the sound continued, and for half an hour one or more mysterious beings swept about me close overhead. As once before, my mind went to Pterodactyls and I imagined a pair of the little [Pg 51]web-fingered creatures launched out from some secret crevice in the distant mountains, for a brief time to hawk about in the light of the Milky Way, peering down with their great eyes, toothed beaks half open, whipping back and forth through the air, now and then snapping up a bat, and stirring the imagination of a curiosity-tortured human, who would willingly give a year of his life to see such a sight.

I had meant to spend part of the night among the mangroves, but the glimmer of the white sand drew me up instead of down the shore, and I crept over the rocks and padded silently over the sand to our swimming beach.

“Silent and smooth as a mirror”

The tide was half-way down, silent and smooth as a mirror with every star doubled. As I watched, they were erased, one by one as if the reflections had become water-logged and sunk, and looking up I saw a mist swept by the high trade-winds across the sky, while around me not a breath of air stirred. I wriggled into a form half below the surface of the sand; I worked down lower and lower until I was at the very edge of the water, which is one of the most wonderful spots in the world. Being there is the very least part of it. Thousands of people are there all through the summer at Coney Island and Margate, but never think [Pg 52]themselves anywhere but swimming at Coney Island or bathing at Margate.

Between tides is really the wildest place left in the world, the truest no-man’s-land, for while you may sail in all waters just beyond or loll in a hotel a few yards behind, you cannot remain where you are except anchored and in a diver’s suit. And whatever man erects there is sooner or later smashed into joyful chunks of cement by the storm waves. The delight of it is to feel yourself as I did at this moment, a third under water, a third buried in solid sand, and the rest of me bathed in and breathing the air. We sometimes feel a thrill at bestriding the border line of two states or countries. How tremendously more wonderful to snuggle close to the three states of matter, solid, liquid and gaseous, and then indeed to realize it and thrill to it with what seems a fourth state—the mental and spiritual.

The crunch of the sand grains, the lap of the water, the breath of air,—it makes the world very primitive and new. Without my flash I can detect no hint either of vegetable or animal kingdom—my little cosmos at the meeting place of the elements is wholly inorganic and mind. If only earth-fire were added, it would be complete, and here, a hundred feet from my cot, there would truly be an epitome [Pg 53]of the primeval earth. I wonder however, whether it is all not more adumbrative of ages to come, when the last animal has fallen, the last leaf shrivelled, and only the inorganic and spirit remain, than of the infinite past.

My day-dreams or rather nocturnal meditations were leading me into hypnotic depths when, with a single bound, I deserted my most ancient medium, water. Momentarily I even left my more recently ancestral acquisition, earth, and entered the third which I had conquered only during the last eight years. Gravitation, faithful through all physical and mental vicissitudes, brought me down with a resounding thump. At first I was simply dazed. What had happened? From the infinite calm of abstract meditation I had been galvanized into the most violent paroxysm, and here I was sitting on the sand, unhurt, stupidly wide awake, with my heart trip-hammering. Then all at once the physical me calmed down and the mental took charge, first in a thrill of excitement at realization of what had happened, then in joyous recognition that, as at a well-planned dramatic dénouement of a play, the miracle had happened. Nature, tired of being ignored, had entered my inorganic make-believe cosmos, completed it and split it apart with a vengeance. Instead of sending a firefly into my ken, [Pg 54]she had been more subtle, and an electric eel had brushed against the sole of my foot, and discharged his diminutive broadside. The shock had been slight, but unprepared as I was and completely relaxed, it had seemed to my nerves like the discharge from a third rail. With my flash I caught a momentary glimpse of the lithe black chap, and I dabbled my hand in his direction, but he eeled away and became one with the dark water.

I could not get back to my former isolation, even if I greatly desired to do so; the eel had changed all that. He seemed so modern, so conventional and specialized an organism drawing the lightning down into the dark waters, and liberating it at the will of his fishy brain.

I rolled over and flattened myself, and with my electric torch held at eye height, horizontally, I entered one of the strangest of worlds,—a beach at black midnight. My mind kept wandering back to my trio of elements, and I thought of the water ouzel which has conquered them all. In the wilderness of western China I have seen this delicate, thrush-like bird run rapidly in and out of a tangle, over leaves and sand to the edge of a high river bank, and then taking wing, fly in and out between the boulders of the stream, finally to dive headlong into the swift water and creep along the bottom, [Pg 55]feeding as it went. Here, in the space of a minute or two, was exhibited mastery of earth, air and water; only the phœnix could claim superiority.

This evening I was to find a living rival to the ouzel, an insect, a cricket, which, like so many wonders, was not in the heart of the Asiatic continent, but at the very door of my British Guiana laboratory. In the level glare of my flash all the beach creatures became unreal and of low visibility, while their shadows took full possession. This fanciful phrase reflected a very real and interesting scientific fact, that the reason for this lay, not in the unusual lighting, as much as in the color of the little people themselves. Picking its way over the sand came a low-swung, weird, blackish thing, whose silhouetted head swung from side to side, and just above it there appeared a fearful thing, on long emaciated legs, which crept nearer and nearer, and finally rushed at the first and sank down upon it. The attack was so sudden and the images relatively so huge that I involuntarily sat up and raised my light. The two images rushed toward me and vanished and my eyes suddenly shifted to nearer focus. I had been watching the shadows of a small insect and a daddy-long-legs, the substance of which now appeared ridiculously small and close to me, with their shadows well under control beneath [Pg 56]them. Slowly I lowered the flash again, and in spite of all I could do, my eyes gradually lost the creatures themselves and followed back along the lengthening lines of legs, to the gargoylesque false phantoms,—the gyrating monstrous phantasmagoria on the sands. Never have I seen a more completely sense-deceiving phenomenon. Sitting up, I looked down upon small, slowly moving, barely distinguishable beach beings; prone, I was surrounded by unnamable apparently ectoplasmic ghosts. If I should accurately describe their anatomy and actions as revealed by my low-hung light they would fit into no living or fossil phylum of earthly organisms. By shifting back and forth I again focussed on the terrible battle going on at my side, and now the giant had lifted the lesser beast bodily in its jaws, and was staggering about, mumbling it as it went. My scientific terms locustid and phalangid faded from mind with their substance, and I lay watching the midnight shadow struggle between Plash-goo and Lrippity Kang.

I had always thought of daddy-long-legs as harmless living skeletons, who clambered aimlessly about and dropped their legs at a touch. Now I found that they could be ravenous beasts, their dwarfed and rounded body swung high aloft on their eight thready legs, creeping over the sand, [Pg 57]and actually running down, pouncing on and killing insects as large as themselves. In this case it was a green grasshopper nymph who was seized, bitten and worried with an unnecessary amount of dragging about and vicious chewing. I leaned slowly forward with my hand lens until I could see every detail, and if daddy-long-legs were magnified in life only fifteen times I should flee in terror from what would be a worse danger than any wold. The horrid eyes, grouped in their solid clump seemed to be even now watching me malignantly, and the great needle-sharp fangs were sunk deep in the grasshopper, and being worked back and forth as the juices of the still living insect were sucked up.

Soon the creature set to work to sever the abdomen from the rest of the insect, and the head and legs fell to the sand, the feet waving slowly and vaguely. The daddy-long-legs did not move, except now and then to lift one or two legs and hold them aloft when a passing ant brushed against them; twenty minutes later it was still there, draining the last drop from the shrivelled grasshopper.

My attention was attracted to the approaching shadow of another spectre, only in this case the shadow was indefinite, humped; it might have enshrouded a low fluttering moth or awkward beetle. Instead of which, when I followed down the shadow [Pg 58]path to its substance there loomed suddenly a figure even more terrifying than the daddy-long-legs. But this was awful in a wholesome way. You started at first sight, then smiled, then felt a liking for the apparition. It was decidedly the Personality of the beach, claiming full attention as long as it was in sight, clownlike in its comicality, and childlike in its seriousness and the affection it aroused. Many will doubtless wonder mildly at thought of the possibility of holding a mole cricket in affection or esteem. Yet it is true that when I return in memory to Kartabo, my thoughts of beauty go to the great blue morpho butterflies, of grace to the soaring vulture, of adorableness to infant sloths, and of amusement and affection to the jolly white mole crickets of the sand.

These are the chaps who fairly outdo the water ouzel, outflying, outrunning and outswimming that bird, and in addition being powerful leapers and the most perfect burrowing machines in the world. Unlike their neighboring relations of the jungle these shore crickets have taken on the color of the sand, keeping only a few hieroglyphics of dark pigment. Their eyes alone remain solid black. No matter how deserted the beach, how lifeless the tropical jungle may seem, I was always certain of finding these optimists abroad after dark, scurrying [Pg 59]here and there, or popping unexpectedly up from the wet sand which a few minutes before had been covered with the tide.

As my new visitor approached, after my first emotion I was able to call him by name, a name as bristling with sharp-angled syllables as the tips of his front legs. Indeed his sponsors must have been profoundly impressed with these great limbs for in Scapteriscus oxydactylus they dubbed him the Shovel-winged, Sharp-fingered One.

In the month of March I found little spurts of wet sand on the upper beach, and following down each tiny hole for an inch, I surprised a diminutive white cricket, almost a replica of the large ones, just hatched and bravely starting out in life for itself. In the following months their numbers sadly diminished and the size of the few remaining individuals increased, being gaugeable exactly by the calibre of their hole which they open when the tide goes down. Now, later in the year, the adult mole crickets were in the full prime of life, vital, virile, meeting on equal terms all the dangers and advantages of nocturnal life on a tropical beach. I appreciated these insects all the more because of their local distribution, being found nowhere up or down the river, except on our short stretch of sandy beach.

[Pg 60]

The hind legs are swollen with muscles for leaping, and with broad, flat soles for pushing, the middle legs are normal supports, but the front ones are a study as scientific, mechanically perfect excavators. There are sharp, horny, downward-projecting pickaxes, lighter pitchforks, backed by spade-shape implements, and bordered with stiff, broom-straw edges for sweeping away the loose débris. In fact this little insect has everything but dynamite for making easy its passage underground. It even has long feelers behind as well as in front of the body.

Like the kick-off of a big football game, or Fred Stone, or a shark on your fish line, when one of my mole crickets came into sight, I knew that something exciting was certain to follow. On this midnight, while the big insect had zigzagged toward me, the tide undermined my sandy elbow-rest, and I slipped. At the first scrape of sand, he put both oxydactyl hands together over his head and half buried himself with three flicks. But he was neither coward nor ostrich and after a moment he had turned and rested his great arms upon the mound of sand, the strangest parody upon Raphael’s cherubs imaginable. His head turned from side to side as he watched, and, I almost added, listened, for the source of danger. I remembered in time [Pg 61]that his ears were on his front arms just below the elbows, sandwiched between the pitchfork and the shovel. He twisted sharply to the left at the same instant that a miniature hidden mine was sprung, and a spray of sand shot upward. Almost before my eye could follow, a second mole cricket appeared, and each saw in the other the summation of all past troubles and future hatreds; they hesitated not a second, but flew at each other.

At first there was considerable side-stepping and feinting, and they whirled about one another until a well-marked ring was worn in the damp sand. Then they clinched and to my horror a leg flew up and off into the darkness. Now the timeworn, and at best inadvisable simile was reversed, and ploughshares as well as shovels, brooms, scissors and pitchforks were in a twinkling transformed into slap-sticks, swords, pikes and daggers. Twice the insects reared up on their hind legs, their arms working like flails. Now and then the lace-like wings unrolled and shot out as balancers, glistening like metal in the light of my flash. One cricket fell for a moment, the other pounced and a whole front arm rolled away. Nothing daunted, and indeed apparently lightened by the loss of his left arm, my cricket leaped at the other and bowled him over. I cheered—they both reared again—and [Pg 62]were washed away in a tiny swirl of water,—the tide had turned and the first of the trios of incoming wavelets had caught all of us unawares. Le duel minuit de les courtilières was over. Each opponent had lost a leg, yet they scampered off and dug in with little appearance of crippling,—one limped a bit and the other sank his well somewhat obliquely, that was all. I remembered my first experience with these crickets, when I confined four together in a glass dish, and next morning found but one, large, plump and happy, surrounded with the crumbs of eighteen limbs; and I recalled the diminution in numbers of the broods of infant crickets, and I wondered whether I had better not slur over part of the home life of my little friends if I wished the mirror of my affection to remain untarnished.

I turned my light toward the water which was lapping shoreward, and on the surface were two white spots, mole crickets again, scurrying here and there with short strokes of the forearms, which had now become efficient oars. They soon sculled to shore and vanished, and a threat of moralizing came into my mind; how wonderful it would be if any of us could so completely master the conditions of life in our environment! Here were two sandy depressions where the crickets had disappeared; in [Pg 63]a few minutes the tide would cover them, and for eight hours thereafter the two bundles of vitality would remain buried beneath the waves, able somehow to breathe and to resurrect, to scamper about on their business of life on what remained of their legs, to spread their wings and fly wherever they wished—one place at least being to the lighted lamp on my laboratory table.

The wash of the tide made me restless and I swept my flash about in a last survey, when I saw a multitude of little orange-red lamps drifting toward me. Holding the light obliquely I saw the wraiths of many shrimps with their periscope eyes illumined by my electric wire. They swam steadily ahead, half blinded by the glare, until suddenly there came Nemesis with a rush and a swirl. I caught sight of long waving tentacles, a gaping mouth, flash after flash of glittering silver, and there at my feet was a catfish, half stranded with its headlong rush. Mindful of poisonous spines I flicked him up the beach with a hand blanket of sand, where he lay protesting with rasping twitters and peevish grunts until I salvaged him.

My last glance at the beach showed something so strange that I turned back, and discovered a wholly new field for enthusiasm. Many years ago I found that tracks in the snow could best be observed [Pg 64]and photographed in slanting rays of the sun, and now my final, casual sweep threw out into strong relief a series of rabbit tracks; this in spite of the fact that I was some two thousand miles from the nearest bunny. Looking down at the tracks they completely vanished, not a depression or marking could be detected, but oblique lighting showed the scar of claw marks, all four feet close together, with a good eighteen inches between leaps. I puzzled long over it, I traced it almost to the water and up to the soft, dry sand. At last a thought came to me, and I went up to where I knew there would be, day or night, a file of leaf-cutting ants. There solemnly watching, and waiting for some favorable omen to begin her midnight supper, squatted my pseudo-rabbit, a huge, friendly grandmother of a toad. She blinked, and I reached down and tickled her side, whereat she grunted and puffed out prodigiously.