Mooney, Buffalo.

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

Mooney, Buffalo.

Many years have now passed away since we were presented with that very interesting and amusing book, the “Natural History of Selborne:” nor do I recollect any publication at all resembling it having since appeared. It early impressed on my mind an ardent love for all the ways and economy of nature, and I was thereby led to the constant observance of the rural objects around me. Accordingly, reflections have arisen, and notes been made, such as the reader will find them. The two works do not, I apprehend, interfere with each other. The meditations of separate naturalists in fields, in wilds, in woods, may yield a similarity of ideas; yet the different aspects under which the same vithings are viewed, and characters considered, afford infinite variety of description and narrative: mine, I confess, are but brief and slight sketches; plain observations of nature, the produce often of intervals of leisure and shattered health, affording no history of the country; a mere outline of rural things; the journal of a traveller through the inexhaustible regions of Nature.

| Residence of the Author—Extensive prospect on the banks of the Severn—Welsh mountains, and passages of the river—Roman encampment upon a British site—Remains of the Romans—Coins—Skeletons of men and horses—Traces of a forest—Soils of the parish—Limestone, its abundance and uses—origin—Rocks formed in the parish by the coral polypi—analysis of—Rocks of deposit—analysis of—Lead ore—Carbonate of strontian—Traveller’s foot burned off—Residences upon Limestone supposed healthy—Employment for laborers—Amount of stone disposed of—A worthy peasant—Analysis of soils considered as fallacious—Dairy processes—Grass lands, their nature—Wild plants—predominating plants in corn-fields—Soils will produce particular herbage—Mode of saving hay—Wheat—Culture of the potato—sorts—expense and profit—effect upon the soil—not considered as injurious—sketch of its history—its introduction—some soils not favorable for the root—introduced later than tobacco—value to mankind—Ignorance of the first habitants of the Cerealia—Tendency of plants to revert to their original creation—Original species of the potato cannot now be ascertained—Component parts of some varieties—Teasel crops—its introduction—culture—gathering—value—its cultivation not injurious to the soil—variety of names—application-consumption—Bad custom in farming—“clatters” | Page 9 to 41 |

| Study of natural history no subject of ridicule—to be made an object in youth—A beautiful Oak tree—magnitude of several trees—uncertain in producing acorns—a history of the oak might be written—all its products valuable—Wych elm—its character—uses—magnitude—name—suffers in early frosts—not beautiful in autumn—The buff-tip-moth—Trees condense moisture—Air under trees—verdure—Utility and agency of foliage—Prevalence of plants in soils—Fetid hellebore—uses—Village doctress—Blossoms of plants—use not manifest—Carpenter bee—What flowers most abundant—design of flowers—application of flowers—love of flowers—emblems—amusements of children—universal ornament—cultivation of flowers—bouquet—Poplar tree—formation of footstalks—its suckers | 41–58 |

| viiiDyers’ broom—gathering—dishonest practice—uses for the dyer—Conformation of flax and silk—Nature of color—Snapdragon—an insect trap—Dogsbane—very destructive—the object mysterious—Glaucous birthwort—Snapdragon vegetates in great drought—Evaporation from the earth—Ivy—its shelter and food for birds and insects—love of ivy—ornament to ruins—its effect—Foxglove—grows only in particular soils—medicinal uses—uncertain application—name—ancient names—Vindication of old epithets—Ancient and modern remedies—Snowdrop—a native plant—remains long in abandoned places—character of the snowdrop—Yellow oat-grass—affected by drought—Vervain—ancient estimation, and application—Druids of Gaul—Ancient and modern virtues—Dyers’ weed—value—uses—cultivation—yellow color—most permanent and common—Brimstone butterfly—Day’s eye—Dandelion—Singular appearance of a grass—Brambles—insect path on the leaves—uses of the bramble—Maple tree—an early autumn beau—fashion followed by others—maple wood a beautiful microscopic object—medicinal properties—leaves punctured by insects—Traveller’s joy—grows in limestone soils by preference—uses—pores of the wood in the microscope—Vessels of plants—uninjured by dry seasons—Seeds of the Clematis | 58–83 |

| Naturalist’s autumnal walk—beautiful, and full of variety—Agaric—beauty and variety—plentiful in Monmouthshire—Agaricus fimi putris—Verdigris agaric—Fungi very uncertain in their growth—Flower-formed hydnum—Mitred helvella—Gray puff ball—Fingered clavaria—Agarics, to be understood, observed in all stages of growth—Perishable nature of created things—Parasitic fungi—laurel—holly—two-fronted sphæria—elm leaves—sycamore leaves—bark of plants—the nut—beech—Odorous agaric—Fragment agaric—‘Stainer’ agaric—Stinking phallus—Mode of propagation—Turreted puff—Starry puff—Morell—Bell-shaped nidularia—Food for mice | 83–95 |

| Marten cat—his capture—well adapted for a predatory life—its skin—Hedgehog—mode of life—always destroyed—prejudices against—cruelty of man—an article of food—sensibility of the spines—Harvest mouse—where found—character—Increase and decrease of animals—Migration of rats—Water shrew—its residence and habits—common shrew mouse—Pale blue shrew—Mole—his actions—character—abundance of—easily discovers his food—structure of his body—fur and hair of animals—flesh of the moles—killed by weasels | 95–108 |

| ixBirds—admiration of—The hedge-sparrow—contingencies of its life—song—example of a domestic character—Willow wren—early appearance—and departure—nest—object of her migration—Difficulty of rearing young birds—Golden-crested wren—Linnet—their song—habits—Bull-finch—character—injurious to trees—preference of food—no destroyer of insects—Robin—character—always found—Song of birds—motives obscure—Chaffinch—beautifully feathered—female, her habits—country epithets—conduct in spring—moisten their eggs in hot weather—Parish rewards for vermin—Blue tom-tit—perishes in winter—mode of obtaining food—stratagems—Birds distinguished by voice—Cole mouse—variety of notes—Long-tailed tom-tit—nests—journeys—eggs—labor to feed their young—winter food—great variety of nests—Goldfinch—beautiful nests—Sufferings of the swallow—Maternal care of a little blue tom-tit—industry—Raven—scared from its nest—faculty of discovering its food—universally found—duration of life—reverence—superstitions wearing out—duration of animal life—aided or injured by man—an old horse—life of man—Crossbill—breeds in England—Rook—suffers in cold and dry seasons—his life in the year 1825—various habits of—detects grubs in the earth—his habits in the spring—associations—senses—Magpie—nests—habits—plunderers of the farm-yard—natural affection—Jay—conduct of the old birds—winter habits—feathers—shrike—nest—young—kills other birds—a sentinel—its mischievous disposition—Stormy petrel—habits—Wryneck—its habits—Birds annually diminishing—Swan pool, Lincoln—Nightingale—migrating birds—Rooks love long avenues—Starlings—great flights—social habits—breeding—a stray bird—actions before roosting—congregate—very attentive to their young—journeyings—Laborious life of birds—Red-start—Starling, brown—habits—a very dusky bird—Hawks capture by intimidation—single out individuals—Early seasons—bring rain—Blooming of the white thorn—Migrating birds—their conduct—Butcher-bird—Gray flycatcher—Thrush—instance of affection—motives of action—utility in a garden—Sparrows—domestic habits—manners—increase—destruction—great consumers of insects—accommodating appetite | 108–150 |

| Creatures associating with man—Common mouse—Rat—House fly—Utility of animals—Conduct of man—The dog—Wheatear—Country amusements often cruel—Supplication for pity—Eggs—their markings—Foolish superstition—Kite—his habits—great capture of—Blackcap—habits—song—nest—food—shyness—habits of our occasional visiting birds—Petty chaps—White throats—Willow wren—Fear of man in animals—Stratagem of a wren—Instinct—Awakening of birds—Early morning—Morning in autumn—Goldfinch—captured—die in the winter—soon reconciled to captivity—Tree-creeper—winters in England—not an increasing bird—Yellow wagtail—Rapacious birds—Passerine birds—Buntings—unthatching corn ricks—Old tokens and signs—White lily—Pimpernel—Mistlethrush—his note—breeds near the dwellings of man—Change of character in birds—Love of offspring—Divine appointments—Jack snipe—solitary habits—Christmas shooter—Association of birds—Peewit—habits—eggs—Prognostications—Hedge fruit—Fieldfares—Redwings—feeding in the lowlands—uplands—Egg of the fieldfare—Rural sounds—notes of birds—Plumage of birds—Song of birds—Woodlark—habits—voice—capture—Language of man—of birds—Note significant of danger—Singing a spontaneous effusion—Variety of note in same species—‘Lady-bird’ note of a song-thrush—Croaking of the nightingale—Admiration of birds—Cleanly and innocent creatures | 150–189 |

| xKnowledge slowly obtained—Entomology a difficult study—Wonders around us—The objects of many insects unknown—Chrysalis of a moth—Four-spotted dragon-fly—Ghost moth—soon destroyed—Specimens of plumage of butterflies—Argus butterfly—a pugnacious insect—combats—Azure butterfly—seldom seen—Hummingbird sphinx—habits—wildness—tamed by familiarity—feigns death—Painted lady butterfly—uncertain in appearing—Marble butterfly—Wasp—Meadow-brown butterfly—Yellow winged moth—Admirable butterfly—Gamma moth—Goat moth—their numbers—odor—power of destruction—Larvæ of phalæena cossus, where plentifully found—Designs of nature—Evening ramble—Insects abounding—ignorance of their objects—Glow-worms—curious contrivance about their eyes—light—migration—Snake eggs—destruction—harmless in England—antipathy of mankind to the race—Paucity of noxious creatures inhabiting with us—Small bombyx—Vigilance—animation—quarrels—Black ant—combats of strength—Red ants—mortality—Yellow ants—winter nests—millipedes—support great degree of cold—Stagnated water—abounding with insects—Newt—his voracity—Water-flea—an amusing insect—observed by boys—Dorr beetle—their numbers—feign death to avoid injury—Cleanliness of creatures in health—Recurrence to causes—Cockchafers—Changes in nature—Death’s-head moth—chrysalides—superstitions regarding the insect—voice—Great water-beetle—its habits and voracity—Hair worm—its object—Nests of a solitary wasp—Hornets—their abundance at times, and voracity—kill each other—Garden snail—its injuries—generally secure from destruction—faculties—small banded snails—their numbers—superstitions concerning them—Earth-worms—numbers of—the prey of all creatures—utility of—drain watery soils—Inattention to the works of Providence | 189–235 |

| Empiricism—Apple-tree blight—progress—injury—White moss rose—Testacellus halotideus—Cure of the American blight—Effect of season on the vegetation—Destruction of grass roots—Honey-dew—Injury to foliage by small moths—Salt winds—Leasing—its profits—an innocent occupation—ordained by the Almighty—Old customs—wearing out—Maypoles—Christmassing—Kitchen bushes—young holly-trees—Singular conceit—Influence of electric atmosphere on vegetation—Anecdote of the finding of a guinea—Hummings in the air—Fairy rings—Spring changes—Periodical winds—Whirly pits—Sinkings in the earth—Lichen fascicularis—Salt winds destructive of vegetation—Spottings on apples—spottings on strawberry leaves—curious agaric—Curious analogy between plants and animated beings | 235–259 |

| The year 1825—its peculiarities and influences—A speedy method of killing insects—Preserving of insects—Pollarding of trees—most injurious—Insects that destroy the ash—The willow rarely seen as a tree—a fine one near Gloucester—Foggy morning—Reeking of the earth—the cause—and utility—Winter of the year—Ice in pools—Law of nature—Winter called a dull season—Nature actively employed—Exhausting powers observed in the air—A minute vegetable product | 259–279 |

| CONTENTS OF APPENDIX. | |

| Notes—Names for Rural Dwellings—Wild Potato—Wych Elm—Carpenter Bee—Rose-Beetle—Dyers’ Broom—Carnivorous Plant—Ivy—Snowdrop—Vervain—Mistletoe—Dyers’ Weed—Brimstone Butterfly—Furze—Maple—Agarics—Marten—Hedgehog—Mole—Shrew. Birds of England; Rook—Linnet—Bull-finch—House-sparrow—Jay—Wood-dove—Kestrel—House-marten—Rock-pigeon—Magpie—Wryneck—Jackdaw—Thrush—Missel-thrush—Blackbird—Cuckoo—Wren—Halcyon—Wagtail—Swift—Goat-sucker—Bustard—Grous—Titmouse—Starling—Fieldfare—Raven—House Fly—Robin—Goldfinch—Sky-lark—Winter Gnat—Butterflies and Moths—Glow-worm—Slow-worm—Dorr, or Clock-beetle—Death’s-head Moth—American Blight—Holly—Provincialisms—Fairy Rings—Æcidium—Pollarding Trees—Ice Floating | 281–330 |

It is now nearly five-and-twenty years since the “Journal of a Naturalist” first appeared in England. The author, Mr. Knapp, has told us himself that the book owes its origin to the “Natural History of Selborne,” a work of the last century, which it is quite needless to say has become one of the standards of English literature; and the reader is probably also aware that the honors acceded to the disciple are, in this instance, scarcely less than those of his master—the Journal of a Naturalist, and Selborne, stand side by side, on the same shelf, in the better libraries of England.

Both volumes belong to a choice class; they are to be numbered among the books which have been written neither for fame nor for profit, but which have opened spontaneously, one might almost say unconsciously, from the author’s mind. The subjects on which they touch are such as must always prove interesting in themselves; like the grass of the field, and the trees of the wood, the xiigrowth of both works has been fostered by the showers and the sunshine of the open heavens; and in spite of so much that is artificial in our daily life and habits, there are hours when all our hearts gladly turn to the natural and unperverted gifts of our Maker.

The History of Selborne, and the Journal of a Naturalist, happen to have been both written in the southern counties of England. Selborne, the parish of which the Rev. Gilbert White was Rector, lies on the eastern borders of Hampshire. Mr. Knapp has not given us the name of his own village; but its position in Gloucestershire is minutely described. He tells us that it stands upon a high ridge of land commanding very beautiful views, including the broad estuary of the Severn, and the rich plains on its banks, while the fine mountains of southern Wales fill up the back-ground; a Roman ferry with the sites of ancient stations, and the lines of old roads of the same people, are visible, and the pretty though unimportant town of Thornbury, with its imposing church and castle, occupy the cliffs on the opposite bank of the river.

with its

xiiiis the only river of any size in England, running north and south. It rises in Wales, at the foot of Plinlimnon, and winding through some of the finest plains on the island, waters the town of Shrewsbury, Worcester, Tewksbury, and Gloucester. How familiar are all these names to American ears; how the scroll of history unfolds before the mind’s eye as we read their titles! During the last century the importance of the Severn, in a commercial sense, was very great indeed; the movement on the broad estuary by which it flows into the ocean, being perhaps greater, at that period, than that of any other European river, with the single exception of the Thames. Many have been the naval expeditions of importance which have sailed from the Severn; the Cabots when bound on the daring voyage which first threw the light of civilization upon the coast of North America, embarked from the wharves of Bristol. Perchance the scanty sails, and heavy hull of their craft, as it made its way sea-ward, may have been watched by some wondering peasant, toiling in the same fields to which the Naturalist has introduced us.

The mountains of Wales, filling the back-ground of the picture sketched in the author’s opening pages, are very different from those with which American eyes are familiar. Bare and bleak, they are usually wholly shorn xivof wood, and far bolder in their craggy outline than our own heights. Snowdon, the most important mountain in Wales, rises to a height of 3700 feet. Standing in a northern county of the Principality it is not, however, to be included in a view from the banks of the southern Severn. But the hills of Glamorgan, and Brecon, especially noticed by Mr. Knapp, are upward of 2000 feet in height, and stamped more or less with the same general character. It often happens indeed, from the boldness of position, and the abruptness of outline, which usually mark the mountains of Europe, that heights of no great elevation produce very striking effects in a view.

The fertile alluvial pastures in the immediate foreground of the picture, are those in which Milton’s rivernymph Sabrina, may be supposed to have strayed:

The little village, the immediate scene of the Naturalist’s xvobservations, appears to have had an uneventful existence. It lies, we are told, “on a very ancient road,” running between the cities of Gloucester and Bristol; doubtless the tide of war and adventure, must often have swept over the track on many occasions, when the interests of England were battled for in the western counties of the kingdom, but only scanty vestiges of its passage have been found in the little community. A few skeletons, accidentally dug up by the road-side, the bones of horses, the iron head of a single lance, are alone alluded to as memorials of some nameless conflict of the period of Cromwell, and his wars. No stern feudal towers, no ambitious monastic edifices appear to have been raised within the limits of the parish; and, in short, the position of the spot is one associated chiefly with simple rustic labors, and rural quiet, a field especially in harmony with the inquiries and pursuits of the lover of nature.

It is with the vegetation of this unambitious region, and with the living creatures by which it is peopled, that the Naturalist would make us acquainted. He tells us of the trees found in the groves and copses of that open country; of the grasses which grow in the meadows on the banks of the Severn; of the grains and plants cultivated in the hedged fields which line his ancient road. He has a great deal to say about the birds which fly to xviand fro, with the passing seasons; about the butterflies, and moths which come and go with the summer blossoms, and he is familiar with the lowliest of the creeping things found upon his path. Such simple lore is never without interest to those who delight in the face of the earth, to those who love to honor the Creator in the study of his works. It is pleasant to know familiarly the plants which spring up at our feet; we like to establish a sort of intimacy with the birds which, year after year, come singing about our homes; and, on the other hand, when told of the wonders of a foreign vegetation, differing essentially from our own, when hearing of the habits of strange creatures from other and distant climates, we listen eagerly as to a tale of novelty.

We Americans, indeed, are peculiarly placed in this respect. As a people, we are still, in some sense, half aliens to the country Providence has given us; there is much ignorance among us regarding the creatures which held the land as their own long before our forefathers trod the soil, and many of which are still moving about us, living accessories of our existence, at the present hour. On the other hand, again, English reading has made us very familiar with the names, at least, of those races which people the old world. From the nursery epic, relating the melancholy fate of “Cock Robin,” and the numerous xviifeathered dramatis personæ figuring in its verses; from the tragical histories of “Little Red Riding Hood,” and the “Babes in the Woods;” from the winged and four-footed company of Gay and Lafontaine, from these associates of our childhood to the larks and nightingales of Shakspeare and Milton, we all, as we move from the nursery to the library, gather notions more or less definite. We fancy that we know all these creatures by sight; and yet neither “Cock Robin,” nor his murderer the Sparrow, nor his parson the Rook, is to be found this side the salt sea; the cunning Wolf whose hypocritical personation of the old grandame, so wrung our little hearts once upon a time, is not the wolf which howled only a few years since in the forests our fathers felled; the wily Fox of Lafontaine,

is not the fox of Yankeeland—albeit we have our foxes too! Neither the Marten,

nor the nightingale who

nor the lark

flies within three thousand miles of our own haunts. Thus it is that knowing so little of the creatures in whose midst we live, and mentally familiar by our daily reading with the tribes of another hemisphere, the forms of one continent and the names and characters of another, are strangely blended in most American minds. And in this dream-like phantasmagoria, where fancy and reality are often so widely at variance, in which the objects we see, and those we read of are wholly different, and where bird and beast undergo metamorphoses so strange, most of us are content to pass through life.

But there is a pleasant task awaiting us. We may all, if we choose, open our eyes to the beautiful and wonderful realities of the world we live in. Why should we any longer walk blindfold through the fields? Americans, we repeat, are peculiarly placed in this respect; the nature of both hemispheres lies open before them, that of the old world having all the charm of traditional association to attract their attention, that of their native soil being endued with the still deeper interest of home affections. xixThe very comparison between the two is a subject full of the highest interest, a subject more than sufficing in itself to provide instruction and entertainment for a lifetime. And yet, how many of us are ignorant of the very striking, leading fact that the indigenous races of both hemispheres, whether vegetable or animal, while they are generally more or less nearly related to each other, are rarely indeed identical. The number of individual plants, or birds, or insects, which are precisely similar in both hemispheres, is surprisingly small.

It will probably be unnecessary to observe that the writer of these remarks must be understood as laying no claim to the honorable position of a teacher, on either of the many branches connected with Natural History; a mere learner herself, she can offer the reader no other guidance than that of companionship, in looking after the birds, or plants, or insects, mentioned by Mr. Knapp. It has indeed been a subject of regret with her, that the task of editing the “Journal of a Naturalist” should not have fallen into hands better able to render the author full justice in this respect. But it is the object of the present edition to prepare this English volume for the American public generally, and for that purpose simple explanations were alone necessary. Anxious, at least, to do all in her power, the editor has consulted the best printed authorities within her xxreach, and she has also availed herself of the valuable and most obliging assistance of Professor S. F. Baird, Major Le Conte, and Mr. M. A. Curtis, while preparing several of the notes, which will be found in the appendix.

August, 1852.

The village in which I reside is situated upon a very ancient road, connecting the city of Bristol with that of Gloucester, and thus with all the great towns in the North of England. This road runs for the chief part upon a high limestone ridge, from which we obtain a very beautiful and extensive prospect: the broad estuary of the river Severn, the mountains of Glamorgan, Monmouth, and Brecon, with their peaceful vales, and cheerful-looking white cottages, form the distant view: beneath it lies a vast extent of arable and pasture land, gained originally by the power of man from this great river, and preserved now from her incursions by a considerable annual expenditure, testifying his industry and perseverance, and exhibiting his reward. The Aust ferry, supposed to be the “trajectus,” or place where the Romans were accustomed to pass the Severn, is visible, with several stations of that people and the ancient British, being a part of that great chain of forts originally maintained to restrain the plundering inroads of the restless inhabitants of the other bank of the river: Thornbury, with its fine cathedral-like church and castle, the opposite red cliffs of the Severn, and the stream itself, are fine and interesting features.

An encampment of some people, probably Romans, occupies a rather elevated part of the parish, consisting of perhaps three acres of ground, surrounded by a high agger, with no ditch, or a very imperfect one, and probably was never designed for protracted resistance: it appears to form one of the above-mentioned series of forts erected by Ostorius, commencing at Weston, in Somersetshire, and terminating at Bredon in the county 10of Worcester—ours was probably a specula, or watchhill, of the larger kind. We can yet trace, though at places but obscurely, the roads that connected this encampment with other posts in adjoining villages. A few years sweep away commonly all traces of roads of later periods, and the testimony of some old man is often required to substantiate that one had ever been in existence within the memory of a life; yet these uniting roads, which, as works, must have been originally insignificant, little more than by-ways, after disuse for above fourteen hundred years, and encountering all the erasements of time, inclosures, and the plow, are yet manifest, and an evidence of that wonderful people, thieves and ruffians though they were, who constructed them. There is probably no region on the face of the globe ever colonized, or long possessed, by this nation, which does not yet afford some testimony of their having had a footing on it; this people, who, so long before their power existed, it was predicted, should be of “a fierce countenance, dreadful, terrible, strong exceedingly, with great iron teeth that devoured and broke in pieces,”

Almost every Roman road that I have observed appears to have been considerably elevated above the surrounding soil, and hence more likely to remain apparent for a length of time than any of those of modern construction, which are flat, or with a slight central convexity; the turf, that in time by disuse would be formed over them, would in one case present a grassy ridge, in the other be confounded with the adjoining land.

Coins of an ancient date, I think, have not been found here;[1] nor do we possess any remains of warlike edifices, or religious endowments. Our laborers have at 11various times dug up by the road-sides several skeletons of human beings, and of horses; they were in general but slightly covered with earth; and though the bones were much decayed, yet the teeth were sound, and appeared most commonly to have belonged to young persons, and probably had been deposited in their present situations at no very distant period of time. With the bones of a horse so found there remained the iron head of a lance, about a foot long, corroded, but not greatly decayed. Unable better to account for these skeletons, we suppose that they constituted, when alive, part of the forces of General Fairfax, and that they fell in some partial encounters with the peasantry when defending their property about to be plundered by the foragers of his army in 1645, at the time he was besieging the castle of Bristol. The siege lasted sixteen or seventeen days; many parties during that time must have been sent out by him to plunder us cavaliers, and contention would take place.

It is foreign to my plan to enumerate, and it might be difficult to discover, all the changes and revolutions which have taken place here; and I shall merely mention, that this district formerly constituted a regal forest, and we find Robert Fitzharding holding it by grant in the time of King John. We have a “lodge farm,” it is true, and the adjoining grange, the “conygar,” i. e. coneygard, the rabbit-keeper’s dwelling, may, perhaps, have been the situation of the sylvan warren; but there are no remains, or any other indications, of a forest ever having been in existence. Names and traditional tales are all that remain in most places now to remind us of the ancient state of England, or to make credible the narratives of our old historians, who lived when Britain was a forest. Where shall we look for the remnants of that mighty wood, filled with boars, bulls, and savage beasts, that surrounded London? Even in our own days, heaths, moors, and wilds, have disappeared, so as to leave no indications of their former state but the name. Woods and forests seem to be the original productions of most soils and countries favorable for the abode of mankind, as if inviting a settlement, and offering materials 12for its use. As colonies increase, wants are augmented; the woods are consumed; the plow is introduced, division of property follows; a total change and obliteration ensues, though the ancient appellation by which the district was known yet continues.

The parish consists in parts of a poor, shattery gray clay, beneath which we find, in some places, a coarse lias; in others a spongy, rough, impure limestone; in other parts a thin stratum of soil is spread over an immense and irregular rock of carbonate of lime, running to an unknown depth: this in many cases protrudes in great blocks through the thin skin of earth. The rock, though usually stratified, has no uniform dip, but trends to different directions; in some places it appears as if immense sheets of semifluid matter had been pushed out of the station it had settled in, by some other or later-formed heavy-moving mass, or met with an impediment, and so rolled up: that these sheets had not fully hardened at the time of being moved is yet made probable by the whole crystallization of the mass being interrupted; so that no part adheres firmly, but separates into small shattery fragments when struck. This substance we burn in very large quantities for building purposes, and for manure, which, by the facility which we have of obtaining small coal, is rendered at the low rate of three-pence a bushel at the kiln. Our farmers, availing themselves of this cheap article, use considerable quantities, composted with earth, for their different crops, at the rate of not less than a hundred bushels to the acre. This is a favorite substance for their potato land. The return in general is not so large as when grown in manure from the yard; but the root is said to be more mealy, and better flavored.

The utility of lime as manure consists in loosening the tenacious nature of some soils; rendering them more friable and receptive of vegetable fibres: it especially facilitates the dissolution and putrefaction of animal and vegetable substances, which are thus more readily received and circulated in the growing plant; and it has the power of acquiring and long retaining moisture; thus rendering a soil cool and nutritive to the 13plants that vegetate in it. The power that lime has of absorbing moisture will be better understood, when we say, that one hundred weight will, in five or six days, when fresh, absorb five pounds of water, and that it will retain in the shape of powder, when slackened, or loosened, as is commonly said, nearly one-fourth of its weight.[2]

That lime rehardens after being made soft, as in mortar, is owing to the power which it has of acquiring carbonic acid—the fixed air of Dr. Black—from the atmosphere; when the stone is burned, it loses this principle, but re-absorbs it, though slowly, yet in time, and it thus becomes as hard as stone again: we unite it with sand to promote the crystallization and hardening. The utility of lime in various arts, agriculture, manufactories, and medicine, is very extensive, and in many cases indispensable; and the abundance of it spread through the world seems designed as a particular provision of Providence for the various ends of creation. Lime, and siliceous substances, compose a very large portion of the dense matter of our earth; the shells of marine animals contain it abundantly; our bones have eighty parts in one hundred of it; the egg-shells of birds above nine parts in ten—during incubation, it is received by the embryo of the bird, indurating the cartilages, and forming the bones. But the existence and origin of limestone are pre-eminent amongst the wonders of creation; nor should we have been able, rationally, to account for the great diffusion of this substance throughout the globe, however we might have conjectured the formation, without the Mosaical revelation. It may startle, perhaps, the belief of some, who have never considered the subject, to assert what is apparently 14a fact, that a considerable portion of those prodigious cliffs of chalk and calcareous stone, that in many places control the advance of the ocean, protrude in rocks through its waters, or incrust such large portions of the globe, are of animal origin—the exuviæ of marine substances, or the labors of minute insects, which once inhabited the deep. In this conclusion now chemists and philosophers seem in great measure to coincide. Fourcroy observed, forty years ago, that “it could not be denied, that the strata of calcareous matter, which constitute, as it were, the bark or external covering of our globe, in a great part of its extent, are owing to the remains of the skeletons of sea animals, more or less broken down by the waters; that these beds have been deposited at the bottom of the sea, immense masses of chalk, deposited on its bottom, absorb or fix the waters, or convert into a solid substance part of the liquid which fills its vast basins.”—Supplement to Chemistry, p. 263. Such are the conclusions of philosophical investigation; and the discoveries of all our circumnavigators fully corroborate these decisions as to formation. Revelation in part accounts for the removal of these stupendous masses; though, probably, unrecorded concussions since the great subversion of our planet have, in remote periods, effected many of the removals of these deposits. We find the basement of many of the South Sea Islands, some of which are twenty miles long, formed of this matter. Captain Flinders, in the gulf of Carpentaria, held his course by the sides of limestone reefs, five hundred miles in extent, with a depth irregular and uncertain; and still more recently Captain King, seven hundred miles, almost a continent, of rock, increasing, and visibly forming:—all drawn from the waters of the ocean by a minute creature, that wonderful agent in the hands of Providence, the coral insect. This brief account of the origin of calcareous rocks was, perhaps, necessary before mentioning an extraordinary fact, that, after the lapse of so vast a portion of time since the basement of the mighty deep was heaved on high, existing proofs of this event should remain in our obscure village.

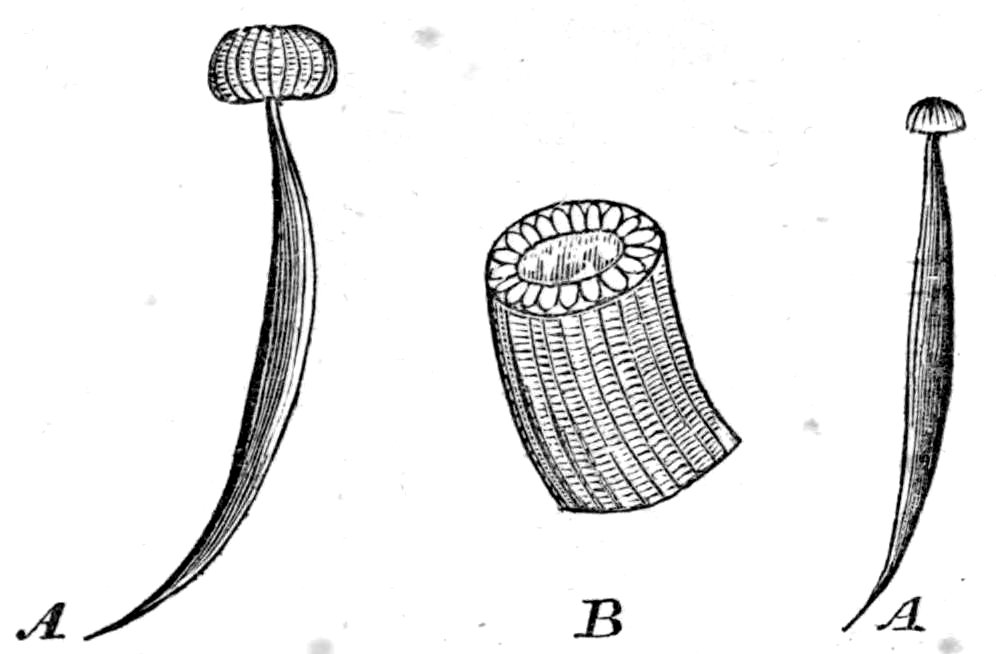

15The limestone rocks here are differently composed but are principally of four kinds—a pale gray, hard and compact; a pale cream-colored, fine-grained and sonorous: these form the upper stratum of stone on our down, a recent deposit, or more probably a mass heaved up from its original station. The whole of this mass, running nearly half a mile long, is obviously of animal formation, a coral rock; a compounded body of minute cylindrical columns, the cells of the animals which constructed the material, the mouths of which are all manifest by a magnifier. The stop in the progress of the work is even visible; soft, stony matter having arisen from some of the tubes, and become indurated there in a convex form; in others the creatures have perished, but their forms or moulds remain, though obscure, yet sufficiently perfect to manifest the fact: these tubes, by exposure to the air for any length of time, have the internal or softer parts decomposed, and the stone becomes cellular. This stone burns to a fine white lime, and is very free from impurities, containing in a hundred parts—

| Carbonate of lime | 88 |

| Magnesia | 8 |

| Silex | 1 |

| Alumine,[3] colored with iron | 3 |

| 100 |

Another quarry presents, likewise, unquestionable evidence of an animal origin, veins of it being composed of shattered parts of shells, and marine substances, greatly consumed and imperfect, embedded in a coarse, gray, sparry compound; an ocean deposit, not a fabrication, and consequently has more impurities in its substance than that of insect formation: it contains about

| Carbonate of lime | 73 |

| Magnesia | 11 |

| Clay | 14 |

| Silex | 2 |

| 100 |

16These two specimens so clearly prove that the original materials of their substance were derived from the deep, that no further arguments need be advanced to support this fact as to our limestone. The former is, perhaps, the mountain limestone of Werner; the latter a variety of dolomite. Our other quarries, as well as the lower strata of the above, present no such indications of animal formation, and they are probably sediment arising from a minute division of shelly bodies now indurated by time and superincumbent pressure and become a coarse-grained marble. Our limestone thus appearing not to be contaminated with any great portion of magnesian earth, it may be used for all agricultural purposes with advantage. Many detached blocks of limestone are found about us, having broken shelly remains; and the joints of the encrinite, greatly mutilated, embedded in them. Irregularly wandering near the lime-ridge is a vein of impure sandy soil, covering a coarse-grained siliceous stone; sand agglutinated, and colored by oxide of iron, resisting heat, and used in the construction of our lime-kilns: the laborers call it “fire-stone.”

We occasionally, though sparingly, find, in a few places on our downs, nodules of lead ore, which induced persons in years past to seek for mineral riches; but the trial being soon abandoned, the result, I suppose, afforded no reasonable ground for success. We likewise find thin veins of carbonate of strontian, but make no use of it; nor is it noted by us different from common rubbish; nor do I know any purpose to which it is peculiarly applicable, but in pyrotechnics. Spirit of wine, in which nitrate of strontian has been mixed, will burn with a beautiful bright red flame; barytes, which approaches near to strontia, affords a fine green; nitrates of both, compounded with other matters, are used in theatrical representations. Strontian exists in many places, and plentifully; some future wants or experiments will probably bring it into notice, and indicate the latent virtues of this mineral.

Perhaps I may here mention an incident, that occurred a few years past at one of our lime-kilns, because it 17manifests how perfectly insensible the human frame may be to pains and afflictions in peculiar circumstances; and that which would be torture if endured in general, may be experienced at other times without any sense of suffering. A travelling man one winter’s evening laid himself down upon the platform of a lime-kiln, placing his feet, probably numbed with cold, upon the heap of stones, newly put on to burn through the night. Sleep overcame him in this situation; the fire gradually rising and increasing until it ignited the stones upon which his feet were placed. Lulled by the warmth, the man slept on; the fire increased until it burned one foot (which probably was extended over a vent-hole) and part of the leg above the ankle entirely off; consuming that part so effectually, that a cinder-like fragment was alone remaining; and still the wretch slept on! and in this state was found by the kiln-man in the morning. Insensible to any pain, and ignorant of his misfortune, he attempted to rise and pursue his journey, but missing his shoe, requested to have it found; and when he was raised, putting his burnt limb to the ground to support his body, the extremity of his legbone, the tibia, crumbled into fragments, having been calcined into lime. Still he expressed no sense of pain, and probably experienced none, from the gradual operation of the fire, and his own torpidity, during the hours his foot was consuming. This poor drover survived his misfortunes in the hospital about a fortnight; but the fire having extended to other parts of his body, recovery was hopeless.

Residences upon limestone soils have generally been considered as less liable than other situations to infectious and epidemic disorders; and such places being usually more elevated, they become better ventilated, and freed from stagnated and unwholesome airs, and by the absorbing principle of the soil are kept constantly dry. All this seems to favor the supposition that they are healthy; but if exempted from ailments arising from mal-aria, inflammatory complaints do not seem excluded from such situations. When the typhus fever prevailed in the country, we were by no means exempted 18from its effects; the severe coughs attending the spring of 1826 afflicted grievously most individuals in every house; and the measles, which prevailed so greatly at the same season, visited every cottage, though built upon the very limestone rock.

This village and its neighboring parishes, by reason of the peculiar culture carried on in them, and the natural production of the district, afford the most ample employment for their laboring inhabitants; nor perhaps could any portion of the kingdom, neither possessing mineral riches, manufactories, or mills, nor situate in the immediate vicinity of a great town, be found to afford superior demand for the labor, healthy employment, and reasonable toil of its population. Our lime-kilns engage throughout the year several persons; this is, perhaps, our most laborious employ; though its returns are considered as fair. In our culture, after all the various business of the farms, comes the potato-setting; nor is this finished wholly before haymaking commences. Teaseling succeeds; the corn harvest comes on, followed shortly by the requirements of the potato again, and the digging out and securing this requires the labor of multitudes until the very verge of winter. Then comes our employment for this dark season of the year, the breaking of our limestone for the use of the roads, of which we afford a large supply to less favored districts. This material is not to be sought for in distant places, or of difficult attainment, but to be found almost at the very doors of the cottages; and old men, women, and children can obtain a comfortable maintenance by it without any great exertion of strength, or protraction of labor. The rough material costs nothing: a short pickax to detach the stone, and a hammer to break it, are all the tools required. A man or healthy woman can easily supply about a ton in the day; a child that goes on steadily, about one-third of this quantity; and as we give one shilling for a ton, a man, his wife, and two tolerable-sized children, can obtain from 2s. 8d. to 3s.[4] per day by this employ, the greater part of the winter; and should the weather be bad, they can work at intervals, and various broken hours, and 19obtain something—and there is a constant demand for the article. The winter accumulation is carted away as the frost occurs, or the spring repair comes on. Our laborers, their children and cottages, I think, present a testimony of their well-doing, by the orderly, decent conduct of the former, and the comforts of the latter. There are years when we have disposed of about 3000 tons of stone, chiefly broken up for use by a few of our village poor; if we say by twenty families, it will have produced perhaps seven pounds[5] to each, a most comfortable addition to their means, when we consider that this has been obtained by the weak and infirm, at intervals of time without more than the cost of labor, when employment elsewhere was in no request.

I may perhaps be pardoned in relating here the good conduct of a villager, deserving more approbation than my simple record will bestow; and it affords an eminent example of what may be accomplished by industry and economy, and a manifestation that high wages are not always essential, or solely contributive to the welfare of the laborer.—When I first knew A. B., he was in a state of poverty, possessing, it is true, a cottage of his own, with a very small garden; but his constitution being delicate, and health precarious, so that he was not a profitable laborer, the farmers were unwilling to employ him. In this condition he came into my service: his wife at that time having a young child contributed very little to the general maintenance of the family: his wages were ten shillings per week, dieting himself, and with little besides that could be considered as profitable. We soon perceived that the clothing of the family became more neat and improved; certain gradations of bodily health appeared; the cottage was whitewashed, and inclosed with a rough wall and gate; the rose and the corchorus began to blossom about it; the pig became two; and a few sheep marked A. B. were running about the lanes: then his wife had a little cow, which it was “hoped his honor would let eat some of the rough grass in the upper field;” but this was not entirely given: this cow, in spring, was joined by a better; but finding such cattle difficult to maintain 20through the winter, they were disposed of, and the sheep augmented. After about six years’ service, my honest, quiet, sober laborer died, leaving his wife and two children surviving: a third had recently died. We found him possessed of some money, though I know not the amount; two fine hogs, and a flock of forty-nine good sheep, many far advanced in lamb; and all this stock was acquired solely with the regular wages of ten shillings a week, in conjunction with the simple aids of rigid sobriety and economy, without a murmur, a complaint, or a grievance!

I report nothing concerning our variously constituted soil, thinking that no correct statement can be given by any detail of a local district under cultivation, beyond generally observing its tendency, as every soil under tillage must be factitious and changeable. As a mere matter of curiosity, I might easily find out the proportions of lime, sand, clay, and vegetable earth, &c., that a given quantity of a certain field contained; but the very next plowing would perhaps move a substratum, and alter the proportions; or a subsequent dressing change the analysis: the adjoining field would be differently treated, and yield a different result. I do not comprehend what general practical benefit can arise from chemical analysis of soils; but as eminent persons maintain the great advantages of it, I suppose they are right, and regret my ignorance. That the component parts of certain lands can easily be detected, and the virtues or deficiencies of them for particular crops be pointed out, I readily admit; but when known, how rarely can the remedy be applied! I have three correspondents, who send me samples of their several farms, and request to know by what means they can meliorate the soil. I find that B. is deficient in lime; but understand in reply, that this earth is distant from his residence, and too costly to be applied. D. wants clay; E. is too retentive and cold, and requires silex or sand; but both are so circumstanced, that they cannot afford to supply the article required. Indeed it is difficult to say what ought to be the component parts of a soil, unless the production of one article or grain is made the 21standard; for differently constituted soil will produce different crops advantageously: one farm produces fine wheat, another barley; others again the finest oats and beans in the parish. To compound a soil of exact chemical parts, so as to afford permanent fertility, is a mere theory. Nature and circumstances may produce a piece of land, that will yield unremitting crops of grass, and we call it a permanently good soil; but art cannot effect this upon a great scale. A small field in this parish always produces good crops; not in consequence of any treatment it receives, but by its natural composition; consisting principally of finely pulverized clay, stained with red oxide of iron, a considerable portion of sand, and vegetable earth: but though I know the probable cause of this field bearing such good wheat, I cannot bring the surrounding and inferior ones into a like constitution, the expense far exceeding any hope of remuneration. Rudolph Glauber obtained gold from common sand, but it was an expensive article! Temporary food for a crop may be found in animal, vegetable, or earthy manures, but these are exhaustible; and when aliment ceases, the crop proportionably diminishes. In one respect, chemical investigation may importantly aid the agriculturist, by pointing out the proportion of magnesian earth in certain limes used for manure, and thus indicate its beneficial or injurious effects on vegetation. I should not like lime containing 20 per cent. of this earth; but when it contains a much smaller proportion, I should not think it very deleterious. This earth acts as a caustic to vegetation, and, neither being soluble in water, nor possessing the other virtue of lime, diminishes the number of bushels used according to its existence, and thus deprives the crop of that portion of benefit: but after all, as Kirwan says, the secret processes of vegetation take place in the dark, exposed to the various and indeterminable influence of the atmosphere; and hence the difficulty of determining on what peculiar circumstance success or failure depends, for the diversified experience of years alone can afford a rational foundation for solid and specific conclusions.

22The real goodness of a soil consists principally, perhaps, in the power it possesses of maintaining a certain degree of moisture; for without this, the plant could have no power of deriving nutriment from any aliment: it might be planted on a dung-hill; but if this had no moisture in it, no nutriment would be yielded; but as long as the soil preserves a moisture, either by its own constituent parts, or by means of a retentive substratum, vegetation goes on. Continue the moisture, and increase the aliment, and the plant will flourish in proportion; but let the moisture be denied by soil, substratum, or manure, and vegetation ceases; for, though certain plants will long subsist by moisture obtained from the air, yet, generally speaking, without a supply by the root, they will languish and fade.

Our dairy processes, I believe, present nothing deserving of particular notice. From our milk, after being skimmed for butter, we make a thin, poor cheese, rendered at a low price, but for which there is a constant demand. Some of our cold lands, too, yield a kind greatly esteemed for toasting; and we likewise manufacture a thicker and better sort, though we do not contend in the market with the productions of north Wilts, or the deeper pastures of Cheshire or Huntingdon.

The agriculture of a small district like ours affords no great scope to expatiate upon: great deviations from general practice we do not aim at; experimental husbandry is beyond our means, perhaps our faculties. Local habits, though often the subject of censure, are frequently such as the “genius of the soil” and situation render necessary, and the experience of years has proved most advantageous.

Our grass in the pastures of the clay-lands, in the mowing season, which, from late feeding in the spring and coldness in the soil, is always late,[6] presents a 23curious appearance; and I should apprehend, that a truss of our hay from these districts, brought into the London market, or exhibited as a new article of provender at a Smithfield cattle-show, would occasion conversation and comment. The crop consists almost entirely of the common field scabious (scabiosa succisa), loggerheads (centauria nigra), and the great ox-eye daisy (chrysanthemum lucanthemum.) There is a scattering of bent (agrostis vulgaris), and here and there a specimen of the better grasses; but the predominant portion, the staple of the crop, is scabious—it is emphatically a promiscuous herbage; yet on this rubbish do the cattle thrive, and from their milk is produced a cheese greatly esteemed for toasting—melting, fat, and good flavored, and, perhaps, inferior to none used for this purpose. The best grasses, indeed, with the exception of the dogstail (cynosurus cristatus), do not delight in our soil: the meadow poa (p. pratensis), and the rough stalked poa (p. trivialis), when found, are dwarfish; and having once occasion for a few specimens of the foxtail (alopecurus pratensis), I found it a scarce and a local plant: but I am convinced, from much observation, that certain species of plants, and grasses in particular, are indigenous to some soils, and that they will vegetate and ultimately predominate over others that may be introduced. In my own very small practice, a field of exceedingly indifferent herbage was broken up, underwent many plowings, was exposed to the roastings of successive suns, and alternations of the year under various crops; amongst others that of potatoes; the requisite hackings, hoeings, and diggings of which alone were sufficient to eradicate any original fibrous, rooted herbage. This field was laid down with clean ray grass (lolium perenne), white trefoil, and hop clover, and did tolerably well for one year: and then the original soft-grass, (holcus lanatus) appeared, overpowered the crop, and repossessed the field; and yet the seed of this holcus could not have lain inert in the soil all this time, as it is a grass that rarely or never perfects its seed, but propagates by its root. The only grass that is purposely sown—trefoils are not grasses—is, I believe, the ray, or rye, no 24others being obtainable from the seedsman: this we consider as perennial; yet, let us lay down two pieces of land with seeds, from the same sack, the one a low, moist, deep soil, the other a dry upland, and in three or four years we shall find the natural herbage of the country spring up, dispute and acquire in part possession of the soil, in despite of the ray grass sown: in the deep soil, the predominant crop will probably consist of poæ, cockfoot, meadow-fescue, holcus, phleum, foxtail, &c.; in the dry soil it will be dogstail, quaking grass, agrostis, &c., not one species of which was ever sown by us. It appears that the herbage of our poor thin clay-lands is the natural produce of the soil, for every fixed soil will produce something, and would without care always exclude better herbage. Attention and manures, a kind of armed force, would certainly support other vegetation, alien introductions, for a time, but the profit would not always be adequate. In a piece of land of this nature I have suppressed the natural produce, by altering the soil with draining, sheep-feeding, stocking up, and composting: and scabious, carnation grass, mat grass, and their companions, no longer thrive; but if I should remit this treatment, they would again predominate, and constitute the crop.

Most counties seem to have some individual or species of wild plants predominating in their soil, which may be scarce, or only locally found in another; this is chiefly manifested in the corn-lands—for aquatic or alpine districts, and some other peculiarities, must form exceptions. This may be in some measure occasioned by treatment or manure, but commonly must be attributed to the chemical composition of the soil, as most plants have organs particularly adapted for imbibing certain substances from the earth, which may be rejected or not sought after by the fibrous or penetrating roots of another. Festuca sylvatica abounds in every soil without an apparent predilection for any one: F. uniglumis, only where it can imbibe marine salt: F. pinnata, is found vegetating upon calcareous soils alone, and I have known it appear immediately as the limestone inclined to the surface, as if all other soils were deficient 25in the requisite nutriment. Many of the maidenhairs and ferns, pellitory, cotyledon, &c. are attached in the crevices of old walls, seeking as it were for the calcareous nitrate found there, this saltpetre appearing essential to their vigor and health. The predominating plants in some corn-fields are the red-poppy,[7] cherlock (sinapis arvensis), mustard (sin. nigra.), wild oat, cornflower (cyanus); but in some adjoining parish we shall only sparingly find them. With us in our cold clay-lands we find the slender foxtail grass (alopecurus agr.) abounding like a cultivated plant: when growing in clover, or the ray grass, the whole are cut together, and though not a desirable addition, is not essentially injurious; but vegetating in the corn, it is a very pernicious weed, drawing nutriment from the crop, and overpowering it by its more early growth, at times so impoverishing the barley or the oats, as to render them comparatively of little value. The upright brome grass (bromus erectus) is a pest in our grass lands, giving the semblance of a crop in a most unproductive soil; hard and wiry, it possesses no virtue as food, and is useless as a grass: this bromus inclines to the limestone, the lias, or clay-stone, as if alumine was required, to effect some essential purpose in its nature; but this is a plant not found universally.

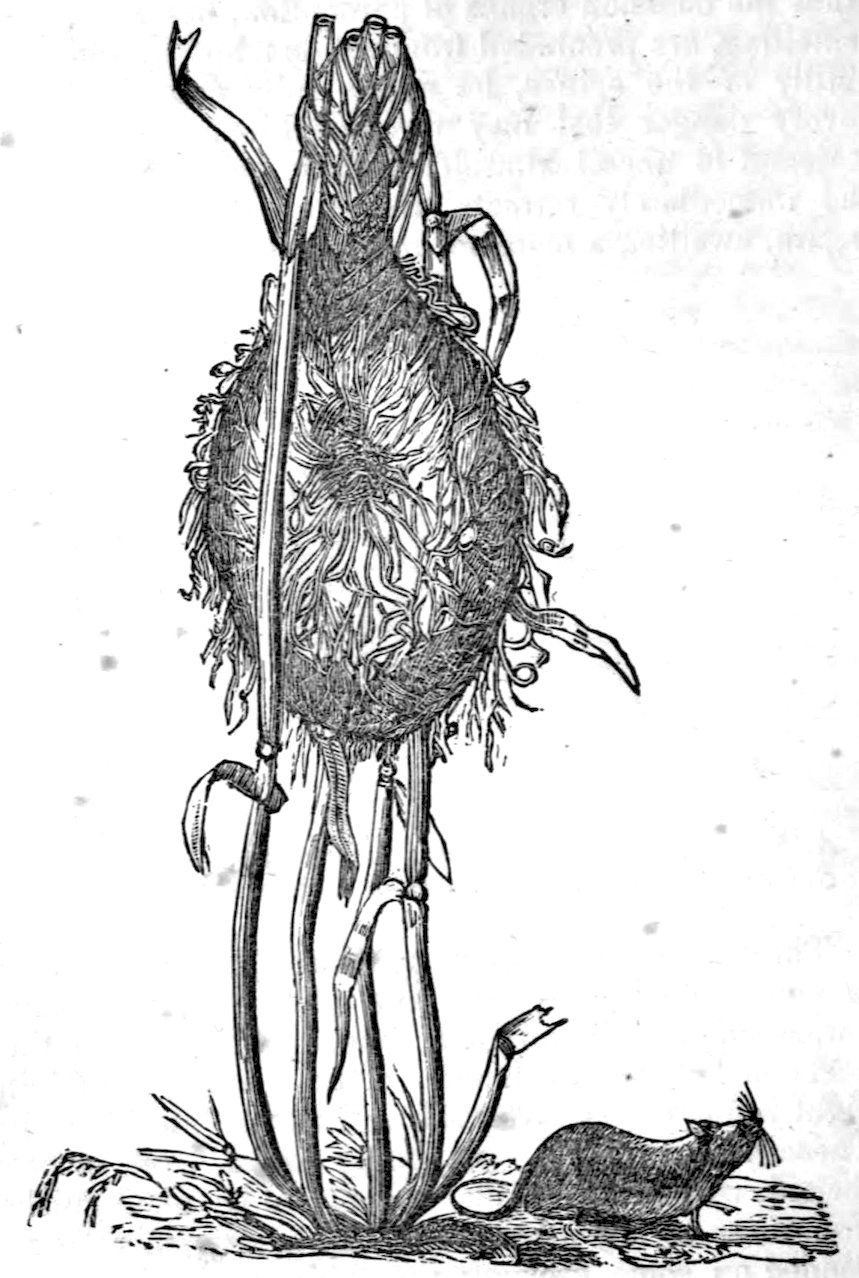

We have in use generally here a very prudential method of saving our crops in bad and catching seasons, by securing the hay in windcocks, and wheat in pooks. As soon as a portion of our grass becomes sufficiently dry, we do not wait for the whole crop being in the same state, but, collecting together about a good wagon load of it, we make a large cock in the field, and as soon as a like quantity is ready we stack that likewise, until the whole field is successively finished, and on the first fine day unite the whole in a mow. Some farmers, in very precarious seasons, only cut enough to make one of these cocks, and having secured this, cut again for another. Should we be necessitated, from the state of the weather, to let these parcels remain long on the ground, or be a little dilatory, which I believe we sometimes are, before they are carried, or, 26as we say, hawled (haled,) the cocks are apt to get a little warm, and only partially heat in the mow, the hay cutting out streaky, and not perhaps so bright or fragrant as when uniformly heated in body: but I am acquainted with no other disadvantage from this practice, and it is assuredly the least expensive, and most ready way of saving a crop in a moist and uncertain season. For wheat it is a very efficacious plan, as these stacks or pooks, (a corruption perhaps of packs,) when properly made, resist long and heavy rains, the sheaves not being simply piled together, but the heads gradually elevated to a certain degree in the centre, and the but-end then shoots off the water, the summit being lightly thatched. An objection has been raised to this custom, from the idea that the mice in the field take refuge in the pooks, and are thus carried home; but mice will resort to the sheaves as well when drying, and be conveyed in like manner to the barn: we have certainly no equally efficacious or speedy plan for securing a crop of wheat, and thousands of loads are thus commonly saved, which would otherwise be endangered, or lost by vegetating in the sheaf.

We will admit that grain, hardened by exposure to the sun and air in the sheaf, is sooner ready for the miller, and is generally a brighter article than that which has been hastily heaped up in the pook; but when the season does not allow of this exposure, but obliges us to prevent the germinating of the grain by any means, I know no practice, as an expedient, rather than a recommendation in all cases, more prompt and efficacious than this.

Two of our crops not being of universal culture are entitled to a brief mention. We grow the potato extensively in our fields, a root which must be considered, after bread corn and rice, the kindest vegetable gift of Providence to mankind. This root forms the chief support of our population as their food, and affords them a healthful employment for three months in the year, during the various stages of planting, hacking, hoeing, harvesting. Every laborer rents of the farmer some portion of his land, to the amount of a rood or more, 27for this culture, the profits of which enable him frequently to build a cottage, and, with the aid of a little bread, furnishes a regular, plentiful, nutritious food for himself, his wife, and children within, and his pig without doors; and they all grow fat and healthy upon this diet, and use has rendered it essential to their being. The population of England, Europe perhaps, would never have been numerous as it is, without this vegetable; and if the human race continue increasing, the cultivation of it may be extended to meet every demand, which no other earthly product could scarcely be found to admit of. The increase of mankind throughout Europe, within the last forty years, has been most remarkable, as every census informs us, notwithstanding the havoc and waste of continual warfare, and most extensive emigration; and as it seems to be an established maxim, that population will increase according to the means of supply, so, if a northern hive should swarm again, or

once more arise, future historians will probably attribute this excess of population, and the revolutions it may effect, to the introduction of vaccination on the one part, and the cultivation of the potato on the other.

The varieties of this tuber, like apples, seem annually extending, and every village has its own approved sorts and names, different soils being found preferable for particular kinds, and local treatment advantageous. We plant both by the dibble[8] and the spade: our chief sorts are pink eyes, prince’s beauty, magpies, and china oranges, for our first crop; blacks, roughs, and reds, for the latter crop; and horses’ legs, for cattle. We have a new sort under trial, with rather an extraordinary name, which I must here call “femora dominarum!” 28But we find here, as is usual with other vegetable varieties, that after a few years’ cultivation the sorts lose their original characters, or, as the men say, “the land gets sick of them,” and they cease to produce as at first, and new sets are resorted to. We have no vegetable under cultivation more probably remunerative than this, or more certain of being in demand sooner or later; it consequently becomes an article of speculation, but not to such an injurious extent as some others are: it gives a sufficient profit to the farmer and his sub renter. Our land is variously rented for this culture; but perhaps eight pounds per acre are a general standard: the farmer gives it two plowings, finds manure, and pays the tithe; the seed is found, and all the labor in and out is performed by the renter; or the farmer, in lieu of any rent, receives half the crop. The farmer’s expenses may be rated at—

| £. | s. | d. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rent to his landlord | 1 | 10 | 0 |

| Two plowings | 1 | 6 | 0 |

| Twelve loads of manure | 1 | 16 | 0 |

| Tithe | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| Rates | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| £5 | 5 | 0 |

leaving him a clear profit of 2l. 15s. per acre. The sub renter’s expenditure and profit will be—

| £. | s. | d. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rent | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Labor in and out | 3 | 0 | 6 |

| £12 | 12 | 6 | |

| £. | s. | d. | |

| Produce 50 sacks, at 6s. 6d. | 16 | 5 | 0 |

| Trash, or small pigs | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| £17 | 5 | 0 |

leaving a profit of 4l. 12s. 6d. per acre. The produce will vary greatly at times, and then the price of the article varies too. The returns to the laborer are always ample, when conducted with any thing like discretion, and the emolument to the farmer is also quite sufficient 29as, beside the rent, he is paid for the manuring his land for a succeeding crop, be it wheat or barley; hence land is always to be obtained by the cotter, upon application. We have a marked instance in the year 1825 how little we can predict what the product of this crop will be, or the change that alteration of weather may effect; for after the drought of the summer, after our apprehensions, our dismay (for the loss of this root is a very serious calamity), the produce of potatoes was generally fair, in places abundant; many acres yielding full eighty sacks, which, at the digging out price of 6s. the sack, gave a clear profit to the laborer of 11l. 7s. 6d.[9] per acre! But at any rate it gives infinite comfort to the poor man, which no other article can equally do, and a plentiful subsistence, when grain would be poverty and want. The injudicious manner in which some farmers have let their land has certainly, under old acts of parliament, brought many families into a parish; but we have very few instances where a potato land renter to any extent is supported by the parish. In this village a very large portion of our peasantry inhabit their own cottages, the greater number of which have been obtained by their industry, and the successful culture of this root. The getting in and out of the crop is solely performed by the cotter and his family: a child drops a set in the dibble-hole or the trench made by the father, the wife with her hoe covering it up; and in harvesting all the family are in action; the baby is wrapped up when asleep in its mother’s cloak, and laid under the shelter of some hedge, and the digging, picking, and conveying to the great store-heap commences; a primitive occupation and community of labor, that I believe no other article admits of or affords.

It has been said that the culture of the potato is injurious to the farm in general, and I know landlords who restrict the growth of it; but perhaps the extent of injury has been greatly overrated. The potato, it is true, makes no return to the land in straw for manure, and a large portion of that which is made in the barton is occasionally required for its cultivation; and thus it is said to consume without any repayment what is 30equally due to other crops: but the cultivation of this tuber requires that the soil should be moved and turned repeatedly; it is generally twice at least plowed, trenched by the spade for sets, hacked when the plant is above ground, then hoed into ridges, and finally, the whole turned over again when the crop is got out: thus is the soil six times turned and exposed to the sun and air and it is kept perfectly free from weeds of all kinds—both of which circumstances are essentially beneficial to the soil. If the potato must have manure, it does not exhaust all the virtues of it, as the crop which succeeds it, be it wheat or barley, sufficiently manifests: there are, besides, exertions made by the renter to obtain this profitable crop, that greatly improve the farm, and which a less promising one would not always stimulate him to attempt—he will cut up his ditch banks, collect the waste soil of his fields, composting it with lime and other matters as a dressing for the potato crop, and it answers well: the usual returns from corn, and fluctuations in the price, will not often induce him to make such exertions. All this is no robbery of the farm-yard, but solely a profitable reward and premium to industry.

Much has been said and written about the potato; but as some erroneous ideas have been received concerning its early introduction into Europe, perhaps a slight sketch of the history of this extraordinary root may not be uninteresting,—a summary of the perusal of multitudes of volumes, papers, treatises!

The sweet Spanish potato (convolvulus batatus), a native of the East, was very early dispersed throughout the continent of Europe; and all the ancient accounts, in which the name of potato is mentioned, relate exclusively to this plant, a convolvulus: but our inquiry at present regards that root now in such extensive cultivation with us, which is an American plant[10] (solanum tuberosum). Perhaps the first mention that is known concerning the root is that of the great German botanist, Clusius, in 1588, who received a present of two of the tubers in that year from Flanders; and there is a plate of it among his rare plants. The first certain account 31which I know of by any English writer is in Gerard, who mentions, in his herbal, receiving some roots from Virginia, and planting them in his garden near London as a curiosity, in the year 1597. All the multiform tales which we have of its introduction by Hawkins, shipwrecked vessels, Raleigh, and his boiling the apples instead of the roots, are merely traditional fancies, or modern inventions, with little or no probability for support. There is some possibility that Sir Walter Raleigh might have introduced the potato into Ireland from America, when he returned in 1584, or rather after his last voyage, eleven years later; but if so, it was much confined in its culture, and slowly acquired estimation, even in that island; for Dr. Campbell does not admit that it was known there before the year 1610, fifteen years after Sir Walter’s final return. In England it seems to have been yet more tardy in obtaining notice; for the first mention which I can find, wherein this tuber is regarded as possessing any virtue, is by that great man Sir Francis Bacon, who investigated nature from the “cedar that is in Lebanon even unto the hyssop that springeth out of the wall: he spake also of beasts, and of fowls, and of fishes, and of creeping things,” in his history of “Life and Death,” written, probably, in retirement after his disgrace. He observes, that “if ale was brewed with one-fourth part of some fat root, such as the potado, to three-fourths of grain, it would be more conducive to longevity than with grain alone.” It was thus full twenty-four years after its being planted by Gerard, that the nutritive virtues of this root appear to have been understood: but with us there seems to have been almost an antipathy against this root as an article of food, which can scarcely excite surprise, when we consider what a wretched sort must have been grown, which one writer tells us was very near the nature of Jerusalem artichokes, but not so good or wholesome; and that they were to be roasted and sliced, and eaten with a sauce composed of wine and sugar! Even Philip Miller, who wrote his account not quite seventy years ago, says “they were despised by the rich, and deemed only proper food for the meaner 32sorts of persons;” and this at a time when that sorry root, the underground or Jerusalem artichoke (helianthus tuberosus) was in great esteem, and extensively cultivated. And we must bear in mind the disinclination, the prejudice I might almost call it, that this root manifests to particular soils. Most of our esculent vegetables thrive better—are better flavored, when growing in certain soils, and under different influences; but the potato becomes actually deteriorated in some land. And every cultivator knows from experience, that the much-admired product of some friend’s domain, or garden, becomes, when introduced into his own, a very inferior, or even an unpalatable root. Potatoes will grow in certain parishes and districts, and even remain unvitiated; but the product will be scanty, as if they tolerated the culture only, and produced by favor; whereas in an adjoining station, possessing some different admixture of soil, some change of aspect, the crop will be highly remunerative. These circumstances in earlier days, when their value, and the necessity of possessing them, were not felt, counteracted any attempt for extensive cultivation, or, probably, influenced the dislike to their use.

However locally this solanum might have been planted, yet it appears, after consulting a variety of agricultural reports, garden books, husbandmen’s directions, &c. down to the statements of Arthur Young, that the potato has not been grown in gardens in England more than one hundred and seventy years; or to any extent in the field above seventy-five. At length, however, as better sorts were introduced, and better modes of dressing found out, it became esteemed; and the value of this most inestimable root was so rapidly manifested, and the demand for it so great, that we find by a survey made about thirty years ago, that the county of Essex alone cultivated about seventeen hundred acres for the London market. I know not the extent of land now required for the supply of our metropolis, but it must be prodigious.

Amidst the numerous remarkable productions ushered into the old continent from the new world, there are 33two which stand pre-eminently conspicuous from their general adoption; unlike in their natures, both have been received as extensive blessings—the one by its nutritive powers tends to support, the other by its narcotic virtues to soothe and comfort the human frame—the potato and tobacco; but very different was the favor with which these plants were viewed: the one, long rejected, by the slow operation of time, and perhaps of necessity, was at length cherished, and has become the support of millions; but nearly one hundred and twenty years passed away before even a trial of its merits was attempted: whereas the tobacco from Yucatan, in less than seventy years after the discovery, appears to have been extensively cultivated in Portugal, and is, perhaps, the most generally adopted superfluous vegetable product known; for sugar and opium are not in such common use. Luxuries, usually, are expensive pleasures, and hence confined to few: but this sedative herb, from its cheapness, is accessible to almost every one, and is the favorite indulgence of a large portion of mankind. Food and rest are the great requirements of mortal life: the potato, by its starch, satisfies the demands of hunger; the tobacco, by its morphin, calms the turbulence of the mind: the former becomes a necessity required; the latter a gratification sought for.

Many as the uses are to which this root is applicable—and it will be annually applied to more; if we consider it merely as an article of food, though subject to occasional partial failures, yet exempted from the blights, the mildews, the wire-worms, the germinatings of corn, which have often filled our land with wailings and with death, we will hail the individual, whoever he might be, who brought it to us, as one of the greatest benefactors to the human race, and with grateful hearts thank the bountiful giver of all good things for this most extensive blessing.

It is a well-known fact, that we are perfectly ignorant of the native sites of nearly all those gramineous plants, distinguished by Linnæus as Cerealia, whose seeds have from the earliest periods of time served for the food of man, such as wheat, rye, barley, rice, maize, oats: perhaps 34we must except the two last, as the oat was discovered by Bruce growing under the culture of nature alone; and he was too good a botanist to have mistaken the identity of Avena sativa—and Indian corn may have been found. That some of them were produced in these regions first inhabited by mankind, we have every reason to believe, and the warrant of something like obscure tradition; but our ignorance of the first habitats of these plants is the less to be wondered at, when we consider that it is more than probable that culture and the arts of man have so infinitely changed the form, improved the nature, and obscured the original species, that it is no longer traceable in any existent state. There appears to be a permission from Nature to effect certain changes in vegetables, yet she retains an inherent propensity in the plant to revert to its original creation, which is very manifest in this particular race, for the sorts which we now make use of will not endure the thraldom of our perversion without the artifices, the restraints of man, but have a constant tendency to return to some other nature, or to run wild, as we call it. Man bears them with him in all his wanderings, by his treatment they remain obedient to his desires, and are identified with colonization, but as soon as he remits his attentions, the seeds perish in the soil, or their offspring dwindle in the earth, and are lost. Or we may say, that Nature, having created these things, permits him, in the sweat of his brow, to effect an improvement, and consigns the custody of them to his care, satisfied that he will preserve them for his own benefit as long as required; when his occasion for them ceases, or when by sloth he neglects them, they return to their original creation: the earth might be cursed to bring forth thorns and thistles, but an attendant blessing and mercy was reserved of permitting them to be cultivated, producing healthful recreation and grateful food. If these are plants of immemorial antiquity, the potato is yet of comparatively modern introduction, but the original species from whence all our endless varieties have emanated cannot probably now be ascertained, man having, as observed above, almost created an essential 35article of food; and it is not unimportant to note the great difference that subsists in the component parts of these varieties—for though, in common estimation, a potato may be a potato, yet we find them very differently compounded. The influence of different temperatures and years may cause these proportions to vary, but I give them as observed in 1828.

| Black or purple, | Fibre | 9¾ | Fecula | 9¾ | Water | 80½ | = 100 |

| Prince’s beauty | do. | 15 | Ditto | 11¾ | Ditto | 70¼ | do. |

| Horse’s legs | do. | 13 | Ditto | 15 | Ditto | 72 | do. |

The proportion of fecula varies greatly, and as the principle of nutriment is supposed to exist in this matter, the value of each sort, if mere nutriment is required, is indicated by this analysis.

The potato may be considered as the most valuable production that Europe has received from the continent of America, and is now, as Bishop Heber informs us, much esteemed in the East, and regarded as the greatest benefit the country ever received from its European masters. A plant that can so climatize and preserve its valuable properties in such different temperatures as northern Europe and Bengal, where the thermometer ranges up to 90 or 100 degrees of heat, must be particularly endowed, and in time will probably become naturalized to every region, and circulate its benefits round the globe. The strenuous manner in which I have lauded this root may, perhaps, excite a smile in some, who only know it as a table viand; but those who have witnessed the blessings which this tuber confers, by affording a sufficiency of food to man and beast, will not be disposed to regard lightly such comforts obtainable by their poorer neighbors.