by Manly Wade Wellman

Like the Darwins and the Huxleys the Wellmans have a quite remarkable record of family accomplishment. Manly Wade’s dad is an internationally famous medical pioneer, painter and writer and his brother, Paul, has achieved outstanding recognition as a best-selling historical novelist. But it is Manly himself we are concerned with here, and his by no means inconsiderable literary talents. There’s a bitter-bright eerie wonderment in this unusual little yarn.

The man from the stars bore the human race no ill will. Why was he greeted by a host of monsters?

“I’ve watched you in the sky,” I whispered, staring in shocked disbelief at the humanoid male from the little space ship. “For three nights, with my telescope.” I gestured toward the roof where the instrument stood. “I made it myself, and I can see the rings of Saturn and Jupiter’s moons. I live alone on this farm, and—” I stopped abruptly, telling myself I was quite mad to think that he could understand me.

“Oh, but I can,” he said instantly. In the gloom he looked just the way you’d expect an inhabitant of another world would look, from his long, thin, snug-garmented arms and legs to his high domed forehead. “I know how to communicate telepathically with your kind,” he said. That made sense, but the rest of it didn’t.

“I can’t believe it,” I said. “The first ship from another world! Why didn’t the big observatories report on your coming?”

“They didn’t see me,” was his measured reply.

“But if my crude, homemade telescope picked you out—”

“I didn’t want them to see me,” he explained patiently. “Too much attention would have been exhausting. I wanted to start, quietly, with you. Long before I set down on your world I decided on you, with your telescope and your lonely home out here away from any densely populated area. Let’s go in.”

As I led him toward my back door I still couldn’t grasp it. He looked too patly like the popular conception of a creature from another planet.

“You can’t grasp it,” he said. “I look too patly like the popular conception of a creature from another planet.”

“You can read my mind?” I gasped, forgetting that he’d just informed me that he had telepathic powers.

“And I can speak your language. As to my appearance—I have adopted a synthetic disguise to avoid startling you too much. If you saw and heard me as I really am, you’d refuse to believe in my existence.”

I opened the kitchen door for him. Inside, his snug garments shone metal-bright. He had large, glowing eyes, and his thin face seemed inscrutably observant and somehow very wise. Just as I closed the door behind us, he goggled upward, and shrank back as though terrified.

“What’s that?” he gasped.

“A moth,” I replied. “It was drawn to the electric light.”

Snatching the little creature out of the air, I crushed it in my fingers and dropped it on the table.

“You did that almost instinctively,” he said. “And ruthlessly.”

“It was only a moth,” I said.

“That was the first time I ever saw a violent death,” he told me. “I’d heard of it, but only as it happens on your world. You see, we’ve studied you, far across space, but we didn’t know you had these little living things—moths, as you call them.”

Looking at him, I wondered if he really was what he claimed to be—an inhabitant of another world.

“I’ll convince you,” he read my mind again, “and you’ll help me convince others. I have thought of a way to make you believe—a scientific way. Gold-making puzzles you, doesn’t it?”

He seated himself at the kitchen table, and drew toward him a tarnished fork. From his belt-pouch he took a small object resembling a salt-shaker and sprinkled dull dust on the utensil. Pouching the shaker, he produced a tiny black vial and carefully trickled liquid on the dust. He twiddled the fork briefly, then held it out. It gleamed yellow, and weighed heavy in my hand. To outward appearance, at least, it was gold.

“What else?” he asked. “Restoring the dead to life?”

Again he produced a vial, and shook a single drop of yellow liquid on the crushed body of the moth. From a tiny syringe, he blew a cloud of vapor. Finally he turned a red glow, like a miniature flashlight, on the insect. Then he shrank back in his chair, for the moth had stirred, and was fluttering up to the light.

Again I swiftly caught and crushed it, and he relaxed. “You’re afraid of your own gift of life,” I said.

He shook his big head. “We’ve studied only your civilized race. We knew of no other living things—uncivilized, uncontrolled. Forgive me if I seem nervous.”

“How did you study us?” I asked.

Close-mouthed, he smiled. “We use mechanisms of awareness. Without optical or auditory experience of you we have familiarized ourselves with even your slipshod, fantastic notions about other worlds. That is why I look and speak as I do, to conform with your notions. I even rigged my vehicle to resemble your mental picture of a spaceship, recognizable to your preconception. I can even achieve complete invisibility. I’ll show myself only to scholars and scientists of your choosing.”

“What name shall I give you?” I asked.

“You could not speak my real name. You may call me Provvorr. That sounds like the name of someone from another world—to you.”

“Where is your world, Provvorr?” I asked. “What is it like?”

“It’s far from your System. We’ll reach a point of en rapportment which will enable you to understand its location. But it is more important that I first know about you.”

I sat down opposite him. “Do you intend to make war upon us?” I asked. “Have you drawn up a plan of conquest?”

Shaking his head, he smiled again. “We have no such plan. We don’t understand killing and conquering. But when I bring my people back, we must understand how to survive here. Our world is overcrowded, exhausted. We’ll colonize this one.”

“But you just said,” I reminded him gently, “that you didn’t want to conquer us.”

Again he smiled. “When we come back you won’t be here, any of you. Our observers give your race something like two of your decades in which to destroy yourselves.”

I looked at him in tight-lipped silence. It was no new idea. Most thinking people agree that we’re on the doorstep of self-extermination. But Provvorr came out with it so facilely, like someone who knows that an apartment will be vacant for him by the first of the month. Only a quite insane mind—

“I’m completely sane,” he assured me.

“You can predict the future. Is that it?”

“Anyone can predict the future who makes a careful, scientific study of the present and the past. Your race will be gone, except for a few scattered survivors, by the time I bring back enough of my people to populate this world.”

He looked at me as he spoke.

“Is there no hope for us then?” I asked. Then I realized with horror that I was accepting his prediction at face value, and almost shouted at him. “This is our world. Do you hear? Ours, not yours.”

“Why begrudge it to me and mine after you leave it empty?” he asked. Then he started violently, staring. “What’s that?”

My sharp voice had summoned Skip, my bull terrier. Entering the kitchen, he stationed himself beside the stove, and he looked at Provvorr.

“It’s just my dog,” I said. “He always gets excited when I raise my voice.”

“This isn’t at all what I expected,” Provvorr said shakily.

Skip stood stiff-legged a yard from Provvorr, and growled almost savagely.

“Get him out of here,” Provvorr pleaded.

“Down, Skip,” I commanded. “That’s it, old fellow. Calm now—” Skip sat down, his eyes still on Provvorr. “There, he won’t harm you,” I said. “He knows you’re frightened, and that makes him foolhardy.”

“But I tried to go invisible,” Provvorr said. “I tried to vanish completely from his consciousness. It should have worked, but—he knows I’m here.”

Provvorr quivered. I stared at him, amazed. “I thought you had pretty thorough impressions of our world.”

“Only of your chief activities and preoccupations. Nothing about the hideous, monstrous creatures you call dogs.”

“Perhaps we take dogs too much for granted,” I said. “We should not. They’re our friends.”

“But they’re so—so repellently alien,” he protested. “Not your kind at all.”

I stared at him. “Don’t you have pets and other animals on your world?”

“My people are the only inhabitants,” he explained. “Once there were others—strange and terrifyingly different. So long ago that we see only their remains in our sedimentary rocks.”

His shoulders twitched nervously. I recalled how he’d acted about the moth, and began to understand the creepy strangeness which was making him quake.

“Are there many dogs like this one?” he asked apprehensively.

“Almost everybody has a dog,” I replied. “Or a cat.”

“What is a cat?” he asked, but there was no need for me to enlighten him.

Oscar strolled in after Skip, a four-footed perambulating muff. He sat beside Skip, his green eyes on Provvorr. He purred like an outboard motor. I thought Provvorr would leap out through the window glass.

“A cat,” he said. “You keep him for—what purpose?”

I tried to be reassuring. “Just for his company and respectability. Of course, he catches mice.”

“What are mice?”

As I told him, his face grew tense and sick.

“All are monsters,” he said. “Your world breeds a horrible variety of abnormal creatures. We thought you were like us—a single living species, subduing a planet to your will. These other things are—uncivilized.”

I was quite sure the word didn’t mean exactly what he wanted it to mean. Skip and Oscar were civilized enough, if it came to that. I think he meant that they were uncanny, beyond those mechanisms of awareness he was accustomed to.

“They won’t hurt you,” I assured him. “Watch while I feed them. You’ll see how friendly they are.”

I took a plate of left-over pork roast from the refrigerator and with a sharp kitchen knife I shaved off scraps. Oscar and Skip accepted the repast with well-bred relish.

“What are they eating?” Provvorr wanted to know.

“Meat,” I said. “Animal food—pork.”

“We make our food from the elements,” Provvorr said.

“Synthetics,” I nodded, understandingly. “You’d have to, with no domestic food animals.”

“From what animal does that food come?” I described a pig. Then in more colorful detail, a steer. He drummed his tapering fingers on the table.

“Your world swarms with hideous life,” he repeated.

“It all depends on how you look at it,” I said. “We’re used to it.”

“I’m not.”

“Therefore it gives you the creeps. The way I’d feel in a roomful of snakes.”

“What are snakes?”

I told him. He asked more questions, and I spoke of rabbits that scampered across fields; of fish swarming in streams, and lakes and oceans; of birds in the air; elephants and lions and tigers. He listened, in a silence that grew ever more ominous around him.

“Your planet is infested,” he said. “This is terrible.”

“Why terrible?” I asked, really wanting to know.

He looked sidelong at Skip and Oscar, their sharp white teeth busy with the pork. “Monsters can’t be rationalized. I can’t read their minds. I can’t disappear from them. They are utterly new to my experience.”

They really are terrifying to him, I thought. Like ghosts....

“What are ghosts?” he demanded, instantly.

“Strange, mysterious beings that ignorant people believe in,” I said. “Spirits of dead creatures, of evil intelligences, lurking and spying, ready to do harm.”

“Are they animals,” said Provvorr.

“No,” I told him. “Ghosts are imaginary. Animals are real.”

“Animals,” he said, “are evil intelligences, lurking and spying, ready to do harm.”

“Nonsense, Provvorr,” I tried to reassure him. “Animals know us for their masters. We’ve won mastery over them.”

“But your race kills and conquers,” he said. “Mine doesn’t. That’s why these creatures don’t think I’m a master. And when your race destroys itself, these other races will remain here—”

He rose, shrinking away from Skip and Oscar. “Have you a light to show me to my ship?” he asked.

I took a flashlight and escorted him from the house. Skip and Oscar watched us from the door, in quiet unconcern.

Out in the field beside his ship, Provvorr looked wan in the flashlight’s beam. “Good-bye,” he said. “We won’t attempt to colonize this monster-thronged world. It’s as you said. We would feel as you would feel among snakes. I can understand that feeling as it is registered in your mind.”

“Then,” I said, “if my race ends the way you say, the world will belong to animals. Perhaps dogs will rule—or cats, or mice. Home folks, anyway. Maybe they’ll do better than we could ever hope to do.”

“Since we won’t come here,” said Provvorr, “would you like to know how to avoid destroying yourself?”

“How?” I cried eagerly.

His smile was tight as he studied me carefully. “When I tell you, it will seem simple.”

And how simple it seemed as he told me, just before he left. So simple, the way to stop wars and conquests and destruction—I hope it won’t sound ridiculous when I pass it on to the United Nations.

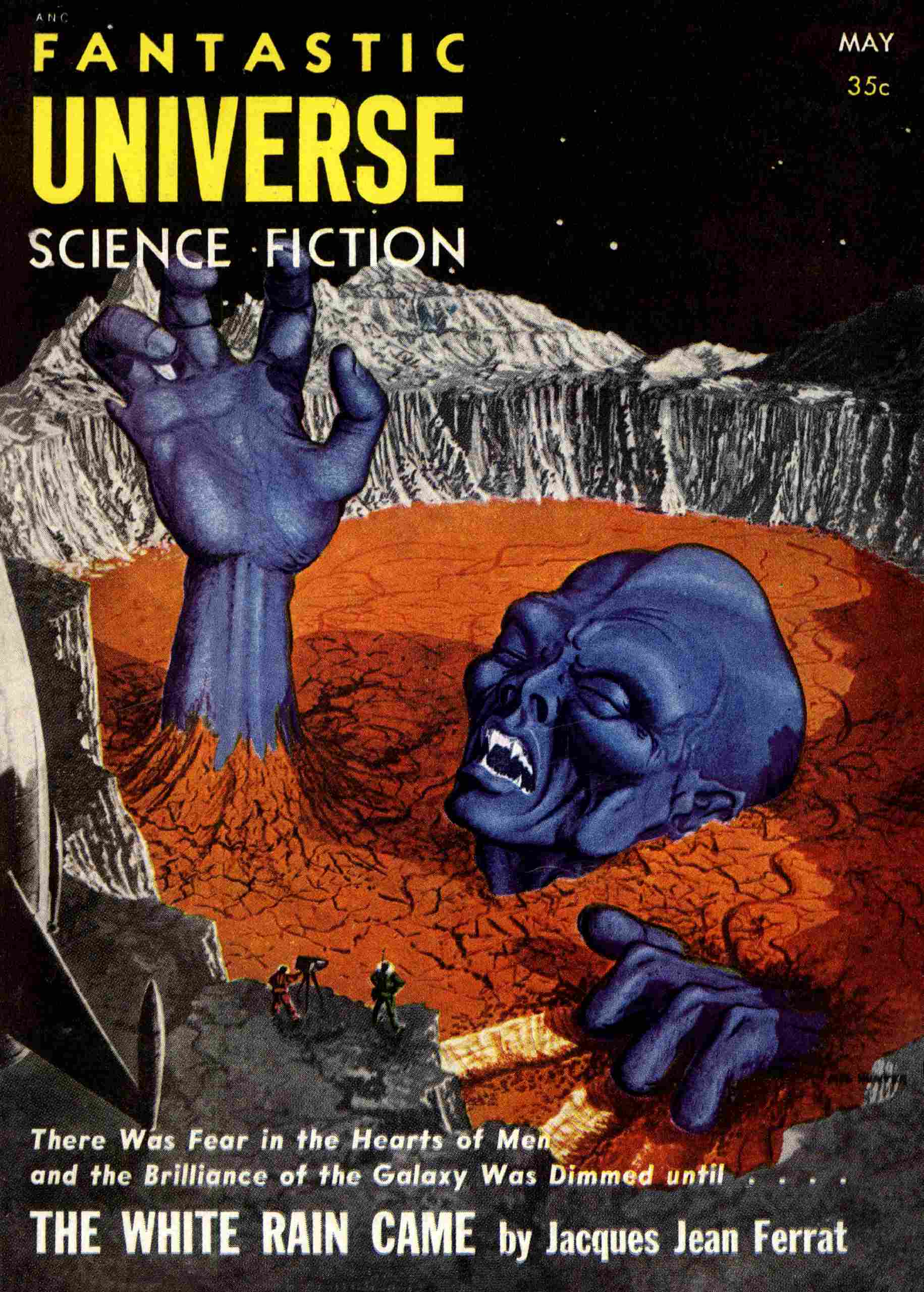

This etext was produced from Fantastic Universe, May 1955 (Vol. 3, No. 4.). Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

Obvious errors have been silently corrected in this version, but minor inconsistencies have been retained as printed.