Large-size versions of illustrations are available by clicking on them.

THE LAST PUNIC WAR

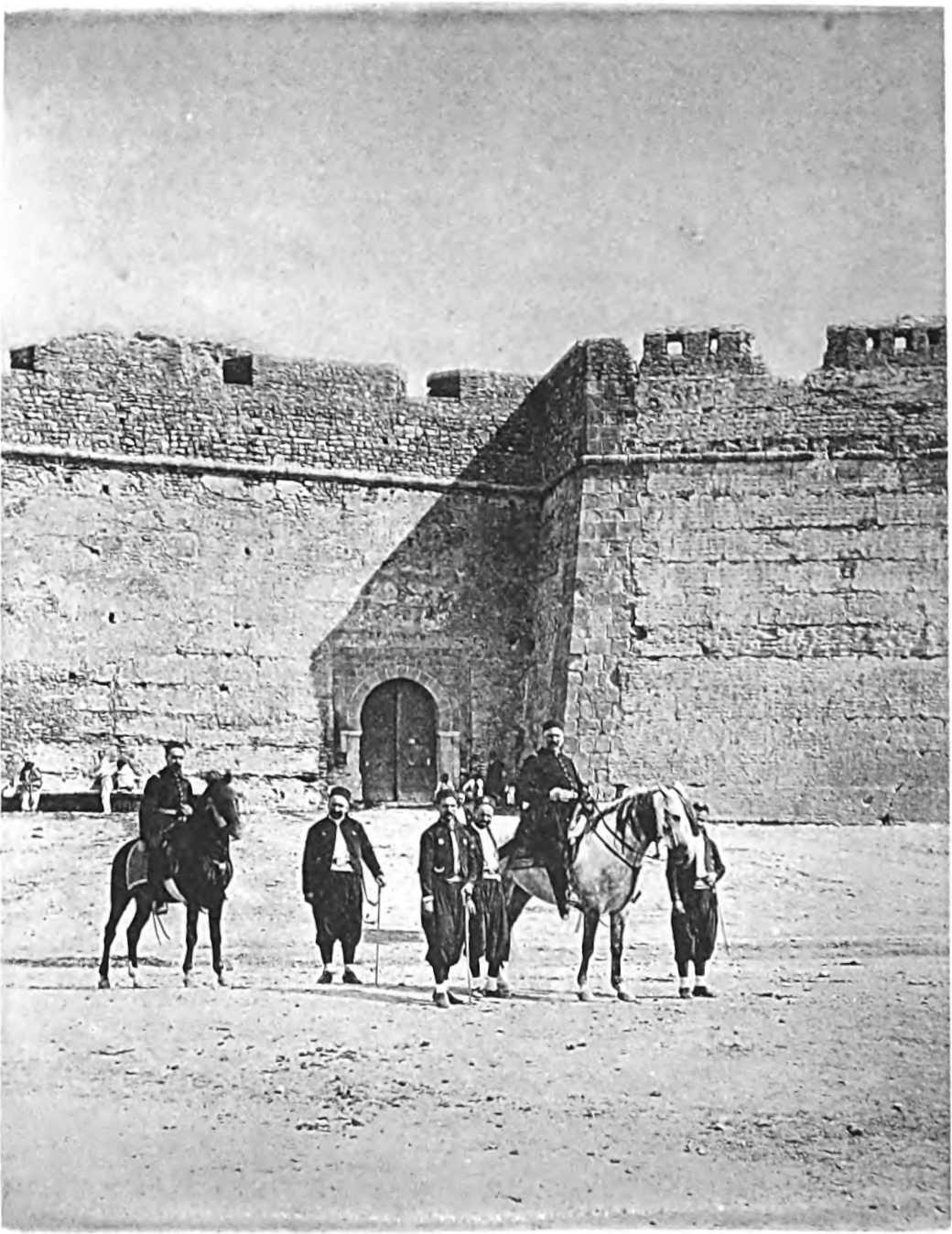

The Governor of the City Waiting the Arrival of the French Troops Outside the Bab-el-Ghadar.

Reproduction by Maclure & Macdonald.

THE LAST PUNIC WAR

TUNIS, PAST AND PRESENT

WITH A NARRATIVE OF THE FRENCH

CONQUEST OF THE REGENCY

BY

A. M. BROADLEY

BARRISTER-AT-LAW

CORRESPONDENT OF THE ‘TIMES’ DURING THE

WAR IN TUNIS

IN TWO VOLUMES.—VOL.

II.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS

EDINBURGH AND LONDON

MDCCCLXXXII

All Rights reserved

[v]CONTENTS OF VOL. II.

![[Decoration]](images/decor1.jpg)

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| XXV. | A REVOLT IN THE CITY OF CUCUMBERS | 1 |

| XXVI. | THE SHELLING OF SFAX | 23 |

| XXVII. | LOOT | 31 |

| XXVIII. | ALARMS AT THE CAPITAL | 48 |

| XXIX. | AUGUST 1881 | 57 |

| XXX. | THE COMING CAMPAIGN | 63 |

| XXXI. | THE MASSACRE OF THE GREY RIVER (OUED ZERGA) | 73 |

| XXXII. | THE FRENCH OCCUPATION OF THE CITY OF TUNIS | 86 |

| XXXIII. | AT SUSA IN THE SAHEL | 102 |

| XXXIV. | FIGHTING IN THE SOUTH | 110 |

| XXXV. | RECRIMINATIONS AND EXECUTIONS | 120 |

| XXXVI. | THE TAKING OF KAIRWÁN | 127 |

| XXXVII. | INSIDE KAIRWÁN | 142 |

| XXXVIII. | AFTER THE VICTORY | 187 |

| XXXIX. | A JOURNEY TO SOUTHERN TUNIS | 199 |

| XL. | TRIPOLI IN THE WEST | 219 |

| XLI. | GENERAL FORGEMOL’S RETURN FROM KAIRWÁN TO TEBESSA | 240 |

| XLII. | TUNIS BEFORE THE TRIBUNAL DE LA SEINE | 247 |

| XLIII. | MORT POUR LA PATRIE | 282 |

| XLIV. | A MONTH OF CHAOS | 306 |

| XLV. | 1882 AND THE FUTURE | 324 |

| [vi]APPENDIX. | |

| PAGE | |

| A.—Instructions issued by the Grand Master to the Knights taking part in the Expedition to Tunis (1835) | 339 |

| B.—The Carraca of Saint Anna, the Great Galley of the Maltese knights | 340 |

| C.—St. George’s Burial-ground near the Carthage Gate at Tunis | 340 |

| D.—The British Treaty with the Dey of Tunis in 1662 | 343 |

| E.—The Confirmatory Convention of 1686 | 344 |

| F.—The British Consulate-General and Political Agency at Tunis, (1640-1882) | 345 |

| G.—Tabarca and the Tabarcans | 346 |

| H.—An Arab Historian’s Account of the French war with Tunis in 1770 | 346 |

| I.—Secret Clause of the French Treaty with Tunis in 1830 | 351 |

| J.—Letter of Muhamed Bey demanding Investiture from the Sultan on his Accession (1855) | 352 |

| K.—Vizirial Letter to Muhamed-es-Sadek Bey concerning a Demand for an Imperial Firman in 1865 | 354 |

| L.—The Firman of 1871 | 357 |

| M.—Project of M. Léon Renaud for a Tunisian Crédit Foncier | 361 |

| N.—Important Notes about the Khamírs and the Invasion of their Province | 363 |

| O.—The Modest Gains of a Tunisian Premier | 370 |

| P.—Strength of the First Expeditionary Corps on the 8th June 1881 | 372 |

| Q.—Enumeration of the Troops sent from France to Tunis to take part in the First Expedition | 372 |

| R.—The movements of Algerian Troops in connection with the First Expedition | 373 |

| S.—Enumeration of the Troops sent from France to Tunis to form the Second Corps Expeditionnaire | 374 |

| T.—Note on the Formation of the Columns taking part in the Concentric Movement on Kairwán (October 1881) | 375 |

| U.—Position and Strength of the French Army of Occupation in the Regency of Tunis on the 1st April 1882 | 376 |

| V.—An American Prophecy about the Destiny of Tunis (1869) | 385 |

| W.—A Foreign Diplomatist’s Note about French Policy in Tunis | 388 |

| X.—Cardinal Lavigerie’s Allocution on receiving Investiture on the Site of Ancient Carthage (April 16th 1882) | 393 |

| Y.—An Intercepted Letter about the Practical and Political Utility of Border Raids | 394 |

| Z.—The Tunisian Export Trade | 397 |

[vii]ILLUSTRATIONS TO VOLUME II.

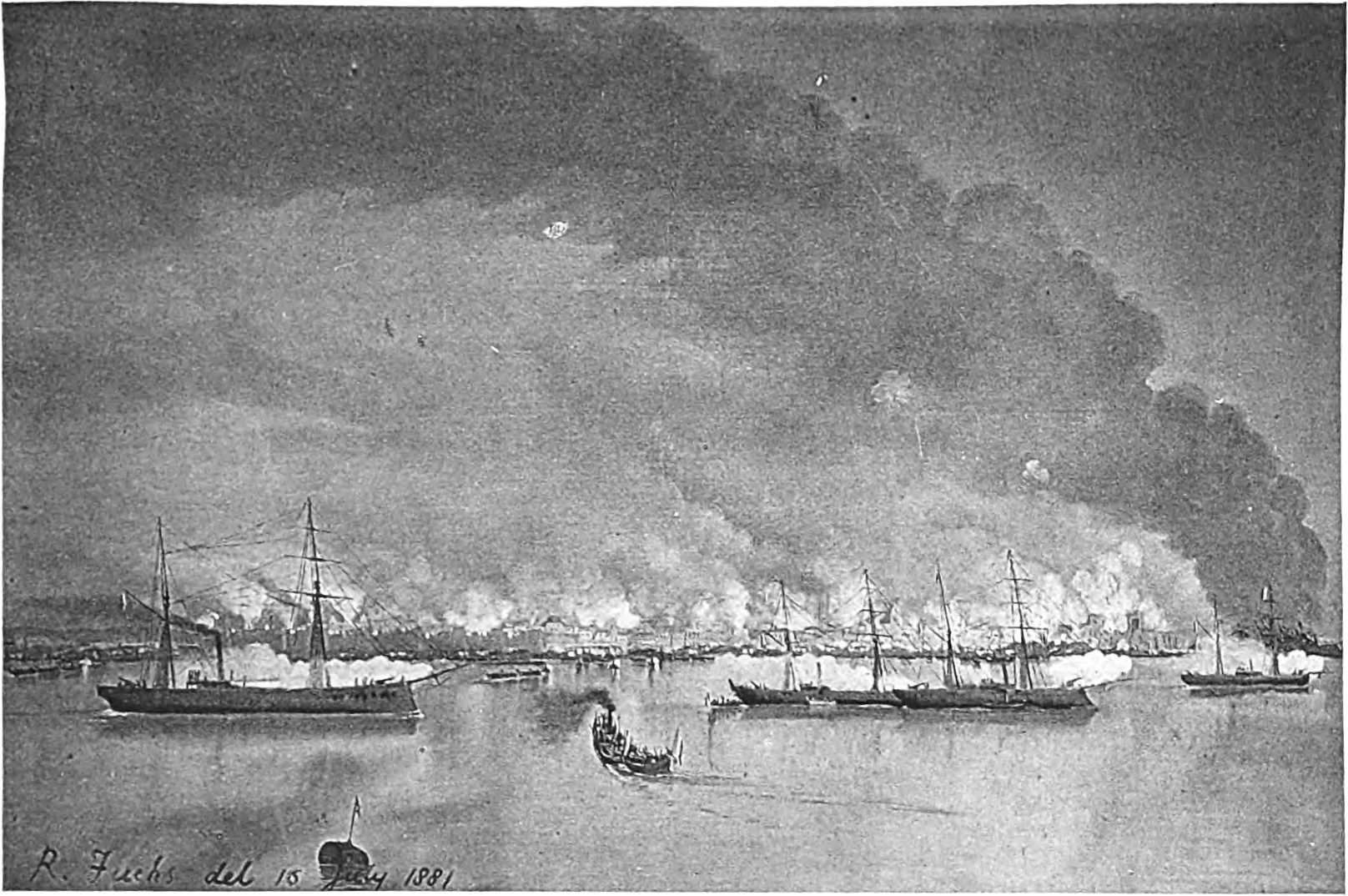

| Bombardment of Sfax, | To face page | 24 |

| Executions on the Railway, | „ „ | 126 |

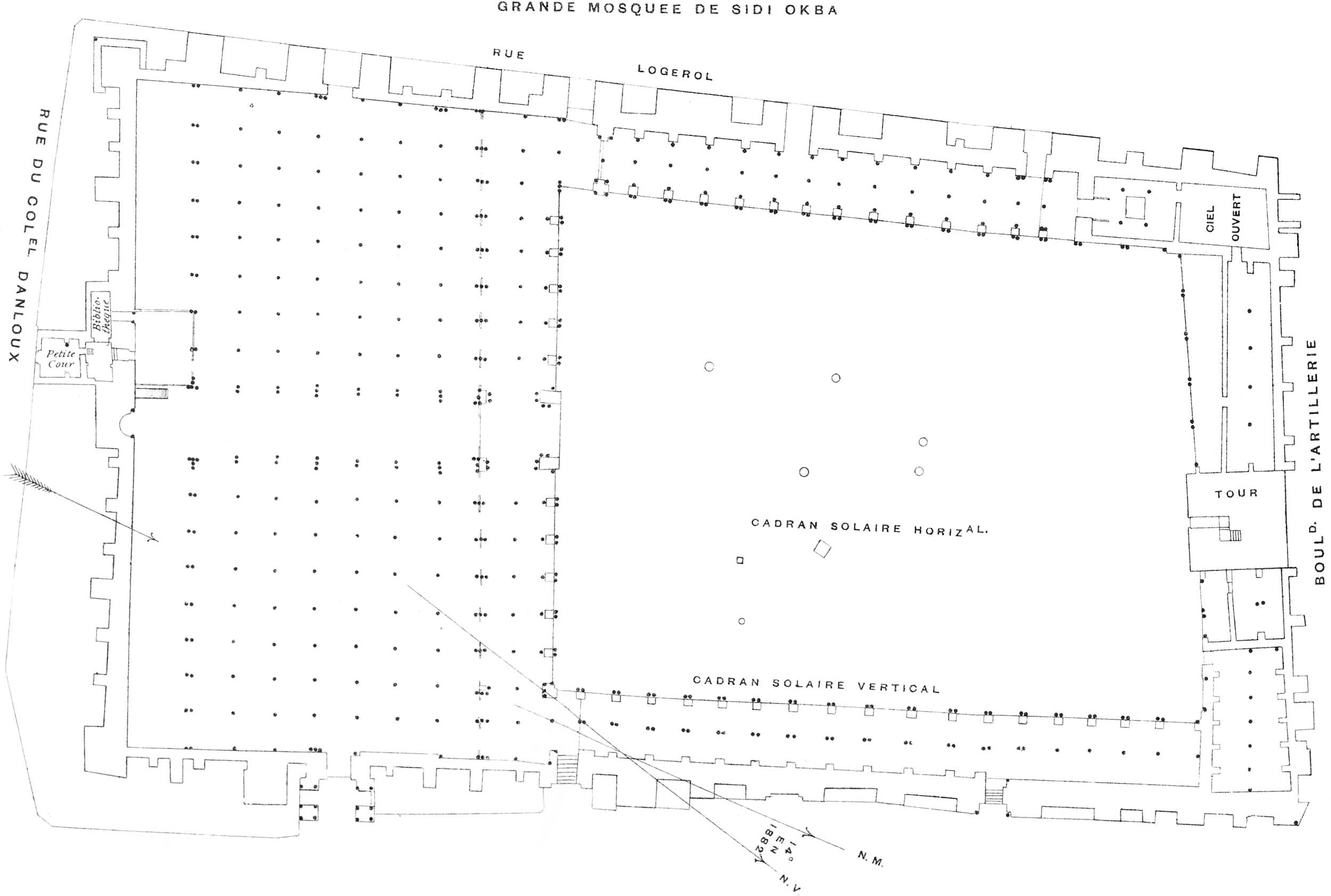

| Plan of Kairwán, | „ „ | 142 |

| The Countess of Bective in an Arab Costume | „ „ | 152 |

| Plan of Great Mosque of Sidi Okhba, Kairwán | „ „ | 158 |

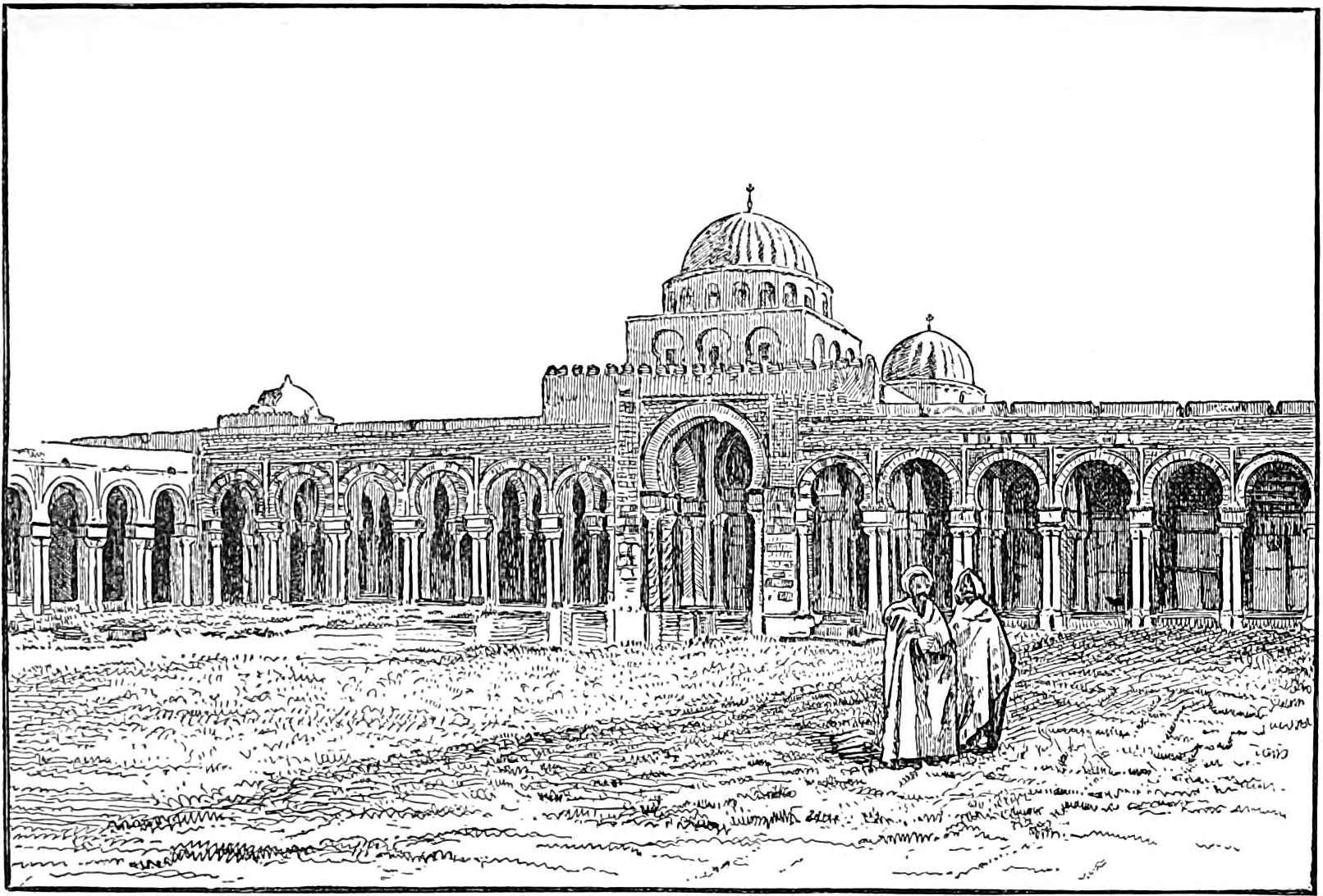

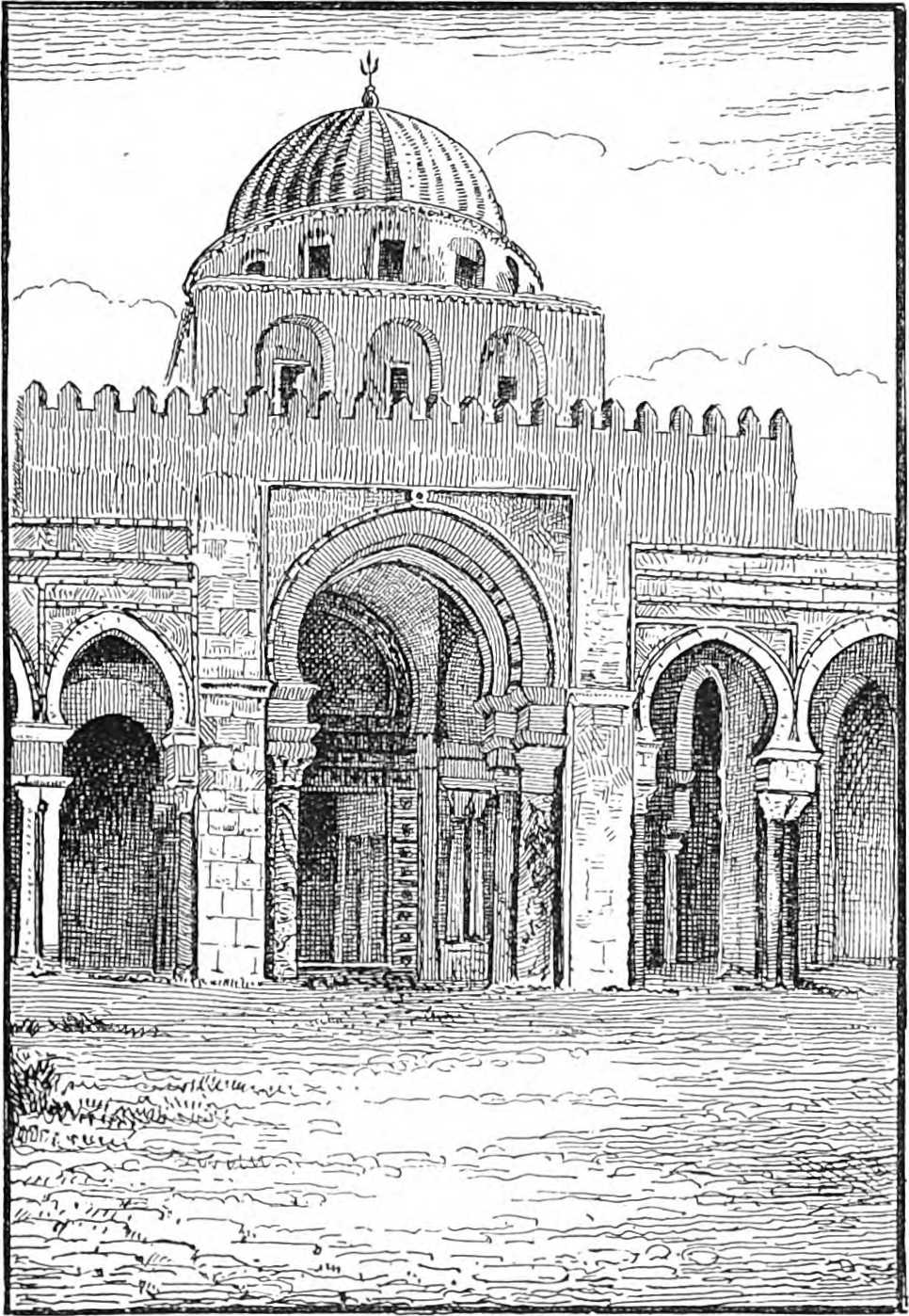

| Mosque of Sidi Okhba at Kairwán, from the Cloisters, | „ „ | 158 |

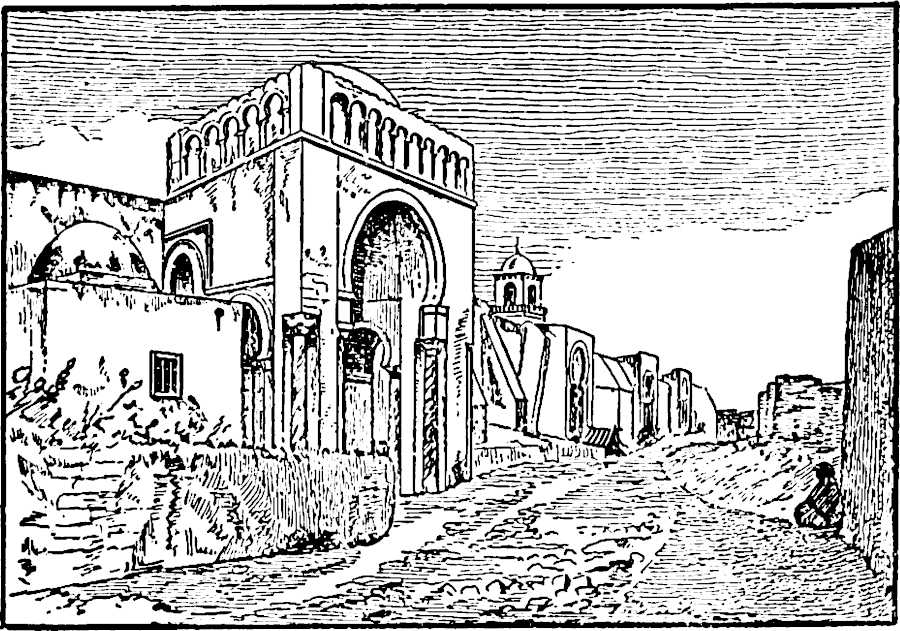

| Door of Prayer-Chamber, Great Mosque, Kairwán, | „ „ | 160 |

| Another View, „ „ „ | „ „ | 160 |

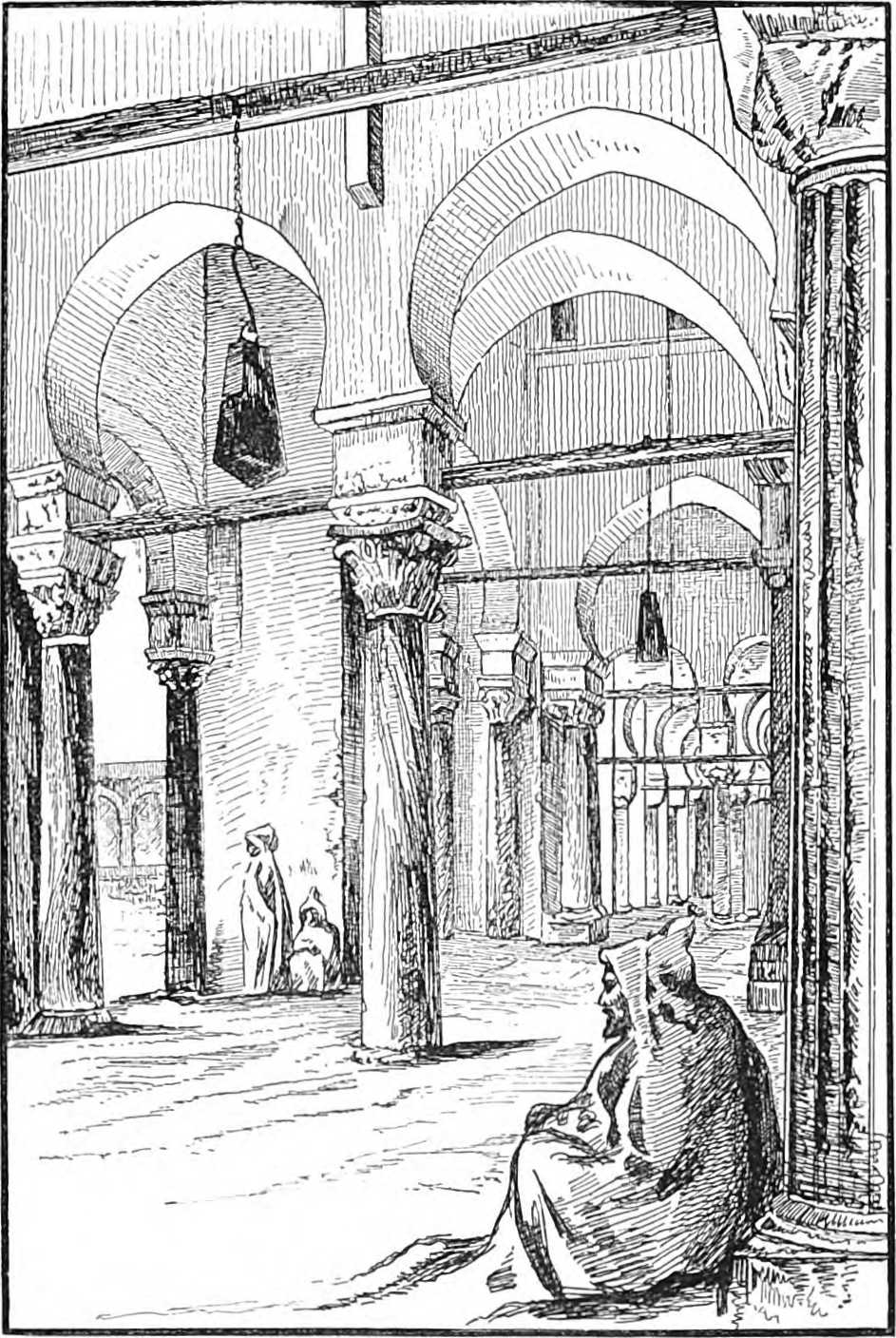

| Interior, Great Mosque, Kairwán, | „ „ | 160 |

| Another View, „ „ | „ „ | 161 |

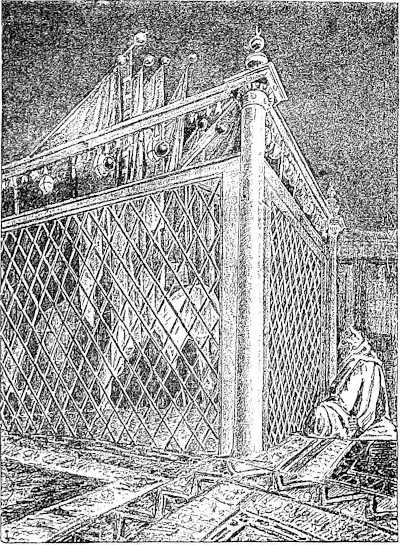

| The Tomb of Sidi-es-Saheb Ennabi, | „ „ | 178 |

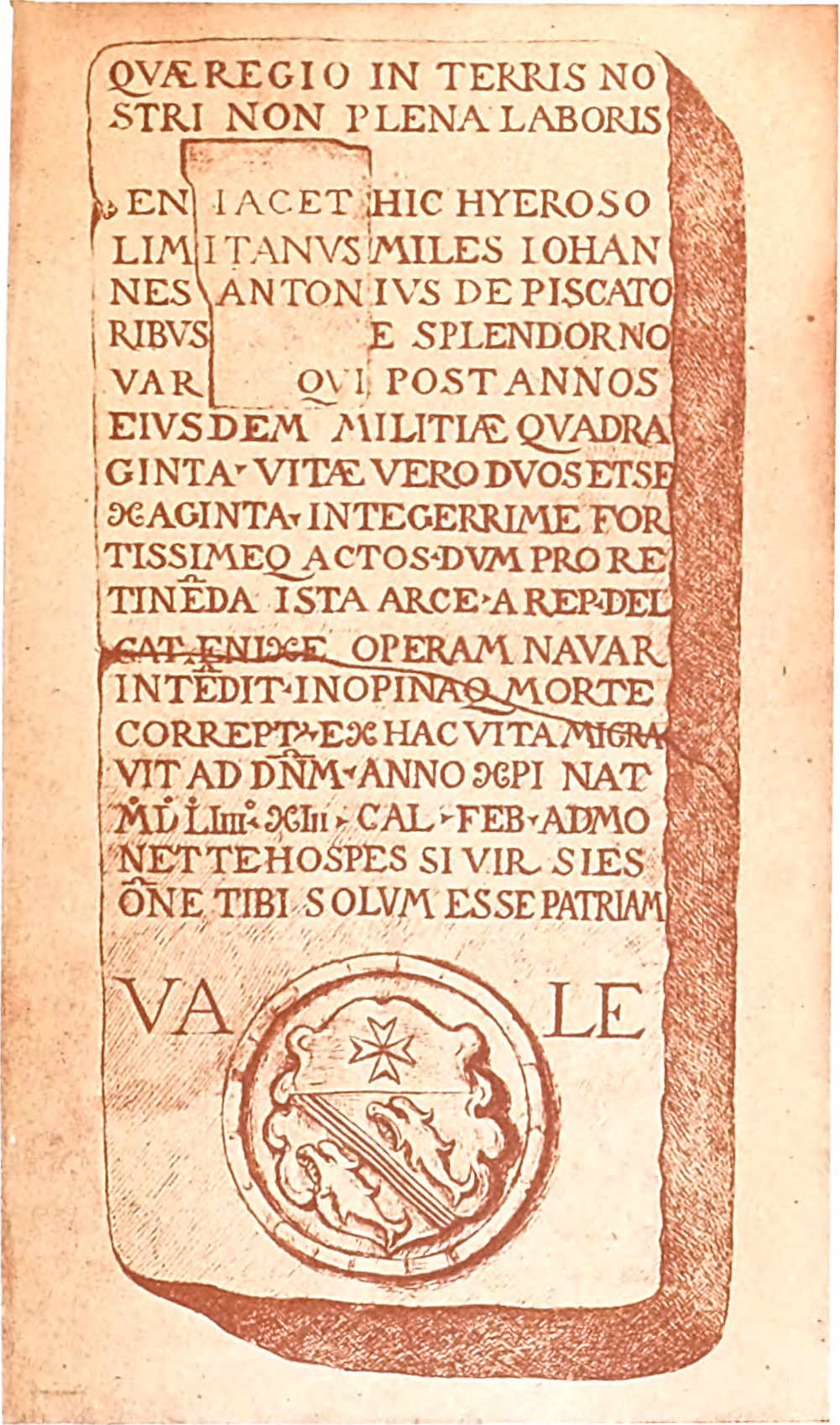

| Inscription on the Tomb of Johannes Antonius de Piscatoribus, | „ „ | 204 |

| Maintenant, il nous faudrait, pour bien Farre, un petit Commandement Militaire, | „ „ | 292 |

[1]TUNIS PAST AND PRESENT.

![[Decoration]](images/decor1.jpg)

CHAPTER XXV.

A REVOLT IN THE CITY OF CUCUMBERS.

In the middle of June M. Roustan was at Tunis busily engaged in advancing the interests of his friends and assuring M. Barthélémy Saint-Hilaire that “perfect tranquillity everywhere prevailed,” and that the prospects were couleur de rose as regards the future. Mustapha was in Paris paving the way to his Grand Cordon by profuse assurances of friendship, and the President of the Republic was as pleased with his diamond ahad, as the Minister of Foreign Affairs was with his diamond nichán. One incident alone troubled the mind of the young Premier, and that was the obstinate refusal of M. Gambetta to enter in any shape the exalted ranks of Tunisian chivalry. Not even the[2] venerable emblem of the Hassanite family in brilliants could tempt the great Republican leader to bedeck himself with a Tunisian trophy.

Just as the proprietors of the Grand Hotel were getting somewhat weary of their Oriental guests, and just as M. Saint-Hilaire was furthering “the mission of civilisation” by making Mustapha, the ex-barber’s apprentice, the colleague of half the sovereigns of Europe in the highest rank of the Legion of Honour, and was rewarding General Musalli for his complacency towards France and her Minister Resident by the cross of a Knight Commander, the Tunisian bubble burst in a moment, and Europe learned that French domination in Tunis meant the possession of the ground her soldiers stood on—and nothing more.

I am now going to tell the history of the national rising in Southern Tunis, according to the journal kept by an eye-witness, Mr. William Galea, who holds the post of British Vice-Consul at Susa, but who happened to be at Sfax during the outbreak, and played an important part in the events of which he speaks. Mr. Galea begins his diary on the 23d June 1881, with an account of his journey by land from Susa to Sfax.

“On Saturday the 18th June I started by carriage to travel along the coast as far as Sfax[3] (‘the City of Cucumbers’). When between Susa and the Roman amphitheatre of El Djem I sat down under an olive-tree while my horses were resting. In a few minutes about thirty Arabs of the Mitelit tribe, accompanied by two Sheikhs, gathered round me. They first wanted to know to what nation I belonged, and when I told them, their spokesman answered that ‘Englishmen were friends of the Arabs,’ and began to talk unreservedly of their feelings and intentions. ‘We are all ready to fight against the French,’ he said, ‘though we know quite well they are more powerful than we are; but at any rate we shall die gloriously and enter Paradise!’ He added that a deputation from the Hamáma, Zlass, and Neffet tribes had already asked their (the Mitelits’) co-operation in case the French troops should enter Kairwán or interfere with that portion of the country. They said also that they had secured the cordial support of the Mourabats (Almoravides) at Kairwán, and would all take the field as soon as they fixed on a competent leader. One of the Sheikhs mentioned that Ali Ben Hlifa (Caid of Neffet) had already declared himself on the side of the Arabs, and that the Bey had sent a commission, or sengiak, to each clan, consisting of ten irregular soldiers under a sergeant-major, to ascertain their intentions. As the persons[4] forming these commissions undoubtedly sympathise with the Arabs, they will as a matter of course echo the hackneyed phrase that ‘tranquillity reigns everywhere,’ and conceal what is really going on, if they do not actually promote it.

“After leaving El Djem I was surprised to see a Mitelit encampment of 300 tents close to the road. This unprecedented fact convinced me of the growing restlessness of the Arabs. When I got to Sfax I found telegrams from my correspondents informing me of the general alarm felt at all points on the coast, and particularly at the menacing attitude now assumed by the most turbulent tribes in the vicinity of the Tripolitan frontier. In some places it appeared that the Arabs had already lost their respect for the Bey, and were determined in any case to assert their independence. All my esparto depôts were threatened, and the Arabs pretend they can now fix any price they like for the grass. So certain I am of a coming disaster that I am chartering as many ships as possible to save all the fibre I can. One of my ships at Gabes was in imminent danger of being fired at, under the mistaken notion that she was bringing French soldiers. The Bey has sent a proclamation to be read at Gabes, and one of my employers was present when this was done. As soon as the Sub-Governor had[5] finished reading it, all the people shouted out with one voice, ‘We will know nothing more of the Bey, for he has become a Christian; cursed be the Bey and his fathers, and the French and their fathers!’ Nevertheless he wrote to Tunis the same evening that peace prevailed. The telegraph to Mahres has been cut, the poles have been burned, and the wire taken, under the mistaken impression that it can be used to make bullets of. Nobody would accompany the surveyor to mend it, so he has come to Sfax with his family. Under pressure, even the peaceful villagers of Mahres have agreed to fight for the common cause. The Hamáma have already attacked the Algerian Arabs and carried off a quantity of their camels and cattle.

“June 24th.—This morning I learn that the revolution is determined upon. Ali Ben Hlifa has been elected the leader of the Arabs, but nobody knows if he acts thus from fear or of his own free will. It is impossible to tell in what direction the Arabs will make their first move, but they will certainly march on Sfax, Gabes, or Kairwán. There can be no doubt that the apparent calm is wholly deceptive, and that before long we shall be in the midst of massacre and bloodshed. The recent slight shocks of an earthquake which have been felt seem to confirm the Arabs as to their notions of French influence,[6] and they are said to have been produced by the incantations of M. Sicard, M. Roustan’s Consular Agent at Gabes, who is commonly reputed to be a wizard. This evening much alarm was occasioned by Giannino Mattei, the French Vice-Consul, sending all his family on board the Bey’s ship in the roadstead.”

I leave Mr. Galea’s journal for a moment to describe the town of Sfax, which is the most important seat of commerce on the Tunisian coast. Situated at the north-eastern extremity of the gulf once known as the Syrtis Minor, “the City of Cucumbers” is built on a plain almost imperceptibly sloping towards the sea, and is surrounded by a narrow zone of sand beyond which is a second zone of fertile land containing an almost countless number of gardens and groves. Sfax, unlike Susa and other places on the coast, is divided into two distinct quarters, one inhabited by the Moslems, and the other by Christians and Jews. The one is wholly, and the second partially, protected by the usual crenellated battlement flanked by towers. The native town possesses two gates, one leading to the open country, and the other opening directly into the European faubourg, at the extremity of which are the batteries and a landing-place. Ships of any burden lie about two miles from the shore,[7] close to which a picturesque flotilla of fishing boats is generally anchored in the shallow sea. Water often fails in Sfax, and two enormous cisterns, maintained by the public charitable trusts and constructed a little to the north of the town, protect it from the dangers of drought. Five mosques, eight sanctuaries, a college, and several schools are to be found in the Arab quarter. Sfax was formerly the starting-point and destination of one of the caravans travelling to and from Central Africa, but this business came to an end with the slave-markets, and its inland commerce is now exclusively confined to the date-producing district and the city of Gafsa. The import and export trade of Sfax has of late years greatly increased, and it is chiefly in the hands of British merchants. At the time when the events of which I am writing occurred, the traffic in the paper-making fibre, commonly known as halfa, or esparto grass, seemed to hold out the prospect of an important future for Sfax; but quite apart from this particular commodity, it receives large quantities of cloth, cotton goods, cutlery, iron, and planks, giving in return oil, almonds, pistaccio nuts, sponges, and wool.

The town and neighbourhood are singularly devoid of all archæological interest. Antiquities there are none, save and except a defaced cross of[8] the Maltese Order over a fountain. The religious buildings are mean, and only two of the mosques have lofty minarets. In the twelfth century Sfax was retaken by the Arabs from the Sicilians, who had conquered it under Roger the Norman, and four hundred years later it was occupied for a short time by the Spaniards. The population amounts to about 15,000 souls, of which 12,000 are Arabs, 1500 Tunisian Jews, 1000 Maltese, and 500 distributed amongst other European nationalities. Fewer Moors, perhaps, live in Sfax than in any other Tunisian seaport, and it is this predominance of Arab blood that accounts for the proverbially militant disposition of its Moslem inhabitants, where and whenever they believe their creed to be in danger.

This, then, was the place where Mr. Galea was writing his diary and shipping his esparto grass in June 1881, and so intelligently foresaw the events which were soon to occur.

On the evening of the 24th June Mr. Galea writes:—“I believe we are in a very serious position here. The French appear to imagine they have attained their object, and gone away triumphantly, leaving the Arabs peaceful and contented. The fire, however, is certainly smouldering under the surface. I cannot really blame the Arabs, when they ask me how we should like to see our country taken by[9] aliens without striking a blow to defend it? The deputation (sangiak) sent by the Government to the Mehedeba tribe has just returned. As soon as the soldiers arrived at the camping-ground the Sheikhs said that ‘the Bey of Tunis was dead to them,’ and after giving them a meal, ordered them to return from whence they came. Two other similar commissions have been turned back by fractions of the Mitelit clan.

“June 25th.—To-day the Governor of Sfax, Caid Hasouna Jelluli, summoned a meeting of the townsfolk, in which he told them that they must be prepared to defend both their own quarter and that of the Europeans against any invasion of the Arabs, observing that this had nothing to do with the French, who were to have no voice concerning Sfax, and that he would bring 200 Tunisian soldiers if they wished it. The citizens assured him that as long as the French kept away they would undertake the defence of the whole place.

“June 26th.—Matters do not seem to be mending. One of the Zlass Caids arrested a Sheikh for using seditious language, whereupon the prisoner’s relatives attacked the guards, using firearms. Two men were killed, and as soon as the Sheikh was liberated he and his party joined the insurgents, to use the term employed by the French to designate those Tunisians[10] who fight for their country. Both the Zlass and Mitelit tribes are, together with the Neffet, gradually approaching Sfax. I hear that our esparto yard at Grín has been plundered. Another of the Bey’s deputations has fared very badly. It was sent to Gabes to see that the broken telegraph was mended, but the villagers of Shinni gave them a sound beating and told them to go back to the Bey. To-day several Beylical decrees arrived for the principal tribes and one for Sfax, to be read publicly. In it the Bey said the French troops were leaving his territory, that the Khamír affair was amicably settled, and enjoined the Sfaxians to pay the taxes peaceably, under pain of severe punishment.

“June 27th.—The French gunboat ‘Chacal’ arrived this morning, and the commander landed to pay a visit to Caid Jelluli. All the Gabes Jews have now come here, and say that numbers of Arab horsemen have arrived there, and that the Bash Mufti has recommended a general union to attack the French. It is rumoured that Tunisian forces are coming here on board a French frigate, under the Bashhamba (General in command of the Bey’s irregular troops), who has been appointed Caid of the Mitelit.

“June 28th.—In the morning everything appeared as quiet as usual. I reached the esparto yard about eight A.M. After I had been there for a few minutes[11] my servant came running from the town, saying that a revolution had broken out. As he was speaking to me I noticed crowds of Arabs, armed with every conceivable kind of weapon, hurrying down to the seaside. Mr. Leonardi had just telegraphed the turn things had taken to Mr. Reade at Tunis, when the wires were cut near where I was standing. In spite of all my efforts, the Arabs who were working for me decamped en masse—some to join the insurgents, others to look after their families. To add to the scene of confusion, the Arab women came on to the housetops and walls of the native town, making the well-known trilling, bird-like sound (in Arabic called zahrit), to encourage their husbands, sons, and brothers in the revolt. Several Hamáma tribesmen who were delivering esparto grass in the yard ran off, leaving both merchandise and money, crying out, ‘Let us fight the French, and gain heaven!’ Just then all the Consular flags were hoisted, but the French colours were again lowered almost immediately. We gave the key of the safe to our head Arab watchman, and collecting the books of the firm,[1] and accompanied by my faithful workmen as a bodyguard, made for the boats. Our men kept shouting out Ingliz, Ingliz (Englishmen), and this was a talisman for us[12] till we got down to the water’s edge. Here an Arab rode at us with a drawn sword, but some of his co-religionists kept him back, declaring we were real Englishmen and should not be touched. At last we reached a boat, and got her off through the mud, for it was low water. All the Europeans were now busy putting their families on board the various small craft available; but on one of the ‘Chacal’s’ boats approaching the jetty ten shots were fired at her. It was only the extreme prudence of the officer in not returning this fire, which prevented a general massacre of the fugitive Christians not yet embarked.

“Meanwhile Giannino, the French Vice-Consul, had reached the ‘Chacal,’ but he had been wounded in the arm during his flight. We went to the ‘Genoese,’ a British steamer, upon which our esparto grass was then being loaded. Later in the afternoon a boat came alongside full of fugitives. I then learned that the French tricolor had been removed by the mob, who also cut down the flagstaff, and that several of the more respectable inhabitants had exerted themselves to facilitate the departure of the Europeans. Alfred Solal, the Swedish Vice-Consul, and his brother were both wounded. Mr. Leonardi, the English Consul, had used every exertion to maintain order amongst the[13] Maltese at this trying moment. When the excitement of the stampede had a little subsided, I began to inquire into the immediate causes of the sudden outbreak. It now appeared that the Governor Jelluli had spread the report that the Bey’s troops were coming, and as the Sfaxians considered the French and the Bey one and the same thing, they cried out, ‘A holy war in the name of God!’ and that they would allow none of the Tunisian soldiers to land. On seeing that all control of the mob was becoming impossible, the chief citizens warned the European colonists that it was time to be off. At the request of the captain of the ‘Chacal,’ I sent off the ‘Genoese’ to Susa with despatches and telegrams, stating what had happened, and we sought another asylum on board the Bey’s steamer the ‘Beshir,’ that had arrived at Sfax two years ago, and becoming unseaworthy was obliged to stay there. All the ships lying off the town were so crowded that there was barely standing room, and the discomfort may be well imagined. After a more careful inquiry the foolish or knavish conduct of Jelluli became apparent. On the 27th it had already oozed out that the Bashhamba was coming there with Tunisian troops. As soon as this was known the principal townsfolk took counsel with the Bimbashi, or Colonel of artillery in[14] charge of the forts, and they all agreed that this was a trick of the Bey to get the batteries out of the hands of the Bimbashi into those of the Bashhamba. Resistance was immediately agreed upon, but Jelluli either knew nothing, or acted as if he was in total ignorance of what was going on. The next morning (the 28th) the Governor called the chief citizens to his house, but a mob of the common people was also allowed to be present. Jelluli[2] then began reading in an almost ironical tone, an amra or decree of the Bey, stating that fifty artillerymen and a Bashhamba were being sent ‘to look after the forts.’ He must certainly have known how such an announcement would be received. The Sfaxians all answered that their old Bimbashi, Muhamed Shareef,[3] was quite able to defend the city, that they would not allow any troops to land, and that they would resist any such measure till death. They ran out into the street in a body calling out, ‘A holy war, a holy war!’ and seizing on all the arms they came across, rushed down to the jetty and seabeach. To make matters worse, messengers had been sent the previous evening to invite the Arabs of the interior to come to[15] Sfax; and as we were embarking, we saw them arriving, shouting, brandishing their weapons, and making all the disturbance they could. The revolution will now spread like wild-fire.

“June 29th.—We have passed an anxious night on the ‘Beshir,’ although the officers did what they could to make us comfortable, but now both water and provisions begin to run short. Several Arab servants we sent to procure them came back wounded, and the Maltese who went themselves did not fare better. Even the Moors who tried to protect any European were themselves at once severely handled. A Maltese boy was literally riddled with bullets and his remains afterwards kicked about the streets. At noon the ‘Mustapha,’ a French mail steamer, arrived in the roads, having placed on board a French frigate she met en route her freight of Tunisian soldiers. She is already overcrowded with passengers for Tunis. Mr. Leonardi has gone to the French ironclad which has just arrived, to ask the commander to serve out provisions and water to the distressed British subjects. Mr. Leonardi is behaving nobly, not only rendering every assistance to the fugitives, but going on shore to try and supply their wants, when each journey becomes more and more dangerous both to life and limb. With glasses we can distinguish the clouds[16] of dust raised by troops of mounted Arabs entering the town.

“June 30th.—In the night a great meeting of Sfaxians and tribesmen was held. Jelluli was dismissed, the Beylical authority declared at an end, and Muhamed Shareef Bimbashi, named Bey and Commander-in-chief. It was stipulated that no more provisions or water were to be furnished to the fugitives, and that no Christian was to be allowed to land under pain of death. We can see the people moving the cannon on the batteries, it is supposed under the direction of the Bimbashi, and making walls and barricades of all my iron-bound bales of esparto-grass. A revolt has now broken out at Mahres, but Gabes is quiet as yet. The Bimbashi has suddenly become more conciliatory, or is trying to lay a trap for us: this morning (nine A.M.) he sent messengers to say that we might all go on shore and buy provisions. In fact, a boat came off to sell bread and a small quantity of water. A green flag has now been hoisted on the Marina battery, but all our national flags are still flying just as we left them in the hurry of departure. Later on, the S.S. ‘Manoubia’ arrived with 1000 Tunisian soldiers, and at two o’clock P.M. a boat went on shore carrying decrees of the Bey addressed both to Jelluli and the ecclesiastical authorities, asking the people[17] to receive the troops in a cordial manner. ‘Yes,’ answered the ex-Bimbashi, ‘we will give them a warm welcome—with gunshot.’ The officer was ordered to leave the place at once, and there are reports that Jelluli himself is a refugee in a sanctuary, as a party is desirous of holding him as a hostage to be killed as soon as any attack commences. At seven P.M. the ‘Manoubia,’ in uncertainty as to the intentions of her crew of malcontent Tunisian soldiers, steamed out to anchor under the guns of the ‘Alma,’ a French frigate which had opportunely arrived during the crisis. The fugitives on board the ‘Chacal’ have been transferred to the ‘Alma,’ and the former boat has left for Susa with despatches. The Bimbashi’s authority is now complete, the green standard of the Prophet has been solemnly saluted, he is greeted everywhere with cries of ‘May God grant you victory!’ and has distributed flint-lock guns and ammunition amongst the people. We are much surprised at the French leaving us all wholly unprotected in case of a night attack, but we extemporised a signal with a red lamp, and later the Vice-Consul Giannino brought us some rockets. All this was very well, but if we had been assailed by the Arabs, we should have been killed or taken prisoners before any assistance could have reached us. My agent at Zarat has[18] escaped from that place on a barque and joined me. He says that a great meeting of tribes has just taken place at the Matmata mountain, twenty-five miles south of Gabes, and that the Ouerghama, Ouerdna, Hemerna, Aleia, Hzim, Hoiea, and Beni Zid, have unanimously agreed to form an army and march up the coast, to either attack the towns, or force the inhabitants to make common cause with them against the invaders. Gabes will be first occupied, and then Sfax and Kairwán. As regards Sfax; the revolution cannot certainly be made more complete than it is already. Zerzis is in the hands of the Arabs, and although Jerba is quiet as yet, it appears that the Ouerghama have ordered the Accara (spongefishers) of Zerzis to prepare boats that they might land in Jerba and pillage it.

“July 1st, 1881.—To-day the Bimbashi sent off messengers to say that all our houses were carefully guarded and to ask if we required anything from them. About noon the ex-Governor, Sy Hassuna Jelluli, came on board accompanied by his nephew and clerks, and said the insurgents had at last decided to allow him to withdraw in safety. He says the Neffet tribe will reach the neighbourhood of Sfax to-morrow. Messengers again came in the afternoon to press us to return on shore, and assuring us that the quarrel of the Arabs was with the[19] Bey and the French, and no one else. For prudential reasons the invitation was not accepted. The encampments of the revolted tribes now line the coast on either side of the town. Towards evening the various consular agents were called on board the ‘Alma,’ and it transpired that a night attack on the Bey’s two ships, upon which we had taken refuge, was meditated. The ‘Beshir’ and the ‘Asad’ were therefore taken in tow, and placed close to the frigate.

“July 2d.—Ali Ben Hlifa arrived to-day with 200 horsemen. A number of the refugees left us, having obtained a passage on board the ‘Italia’ for Malta. My Gabes agent joined me this afternoon, being the last European to quit the place, but he has been obliged to leave all the property of our firm in the hands of the rebels, who, when he left, were calling out ‘jihad, jihad,’ and threatening to kill any Frenchman who landed. M. Sicard, the supposed originator of the earthquakes, had a very narrow escape indeed.

“July 3d.—The Arabs have now formed a regular Medjlis, or tribunal of forty members, who are charged with the administration of justice and the maintenance of good order amongst the inhabitants in Sfax. I hear that the townspeople have sent their wives and children to the most[20] distant gardens, as they believe that the town will be destroyed in the inevitable bombardment, but nevertheless they are determined to fight to the last. Ali Ben Hlifa is now recognised as the leader of the revolted tribes. The Tunisian soldiers on the ‘Manoubia’ have almost openly revolted, and say they will not let the Sfaxians fight for their country alone. Many have jumped into the sea and tried to swim the four miles which intervene between the ships and the shore. Three were picked up by Moorish boats and safely landed. In the afternoon Jelluli sent a messenger to the Bimbashi, to urge on him to submit to the Bey, telling him that the Tunisian troops would otherwise be landed, and inviting him to hoist a white flag on the kasba in token of an affirmative answer. After sunset H.B.M.’s ships ‘Monarch’ and ‘Condor’ anchored in the roads, to the intense relief of the Maltese refugees.

“July 4th.—Early in the morning several Tunisian soldiers were detected swimming towards the shore, and a little later 100 of them were to our dismay placed on board the already-overcrowded Bey’s steamers. Their mutinous spirit is so apparent that we are almost more afraid of them than of the Arabs in the town. Captain Tryon, C.B., of the ‘Monarch,’ has humanely ordered the distribution of water[21] and provisions to the needy of all nations amongst the fugitives. Moorish boats with eatables for sale hovered round the ships for a great part of the day.

“July 5th.—Ali Ben Hlifa yesterday sent messengers to all the coast towns explaining the action he had taken, and asking for aid. The Arabs are working hard at a ditch and other defences, and the Council of Forty condemns people to death for the smallest offences against person or property. It has been arranged that if an attack takes place, Muhamed Khemoun[4] will be president of the tribunal. All the carpenters in the town are employed in making carriages for the cannon, and relays of workmen are engaged in erecting a barricade across the front of the town. The Mitelit, Neffet, Zlass, Hamáma, and Ouerghama tribes now entirely surround the place, and other clans and fractions of clans have promised to join them, and are not far off. The chiefs exhibit letters promising not only the aid of the Tripoli tribes, but of 10,000 Turkish troops. A fearful responsibility rests on the authors of such communications, for the existence of which I can vouch. There is something to admire in the order preserved by the Sfaxians, although they are now in the wild excitement of a religious war; notwithstanding[22] that the agents of the Financial Commission have abandoned entirely the collection of all local and custom-house dues, the townspeople have actually continued to enforce their payment, and have appointed suitable persons to see that no injustice is committed in this respect. A large French troop-ship arrived to-day, with soldiers on board, and another French gunboat—the ‘Pique.’ The ‘Chacal’ and the boat just arrived are approaching the shore, and the storm of a bombardment is now about to burst on the devoted heads of the brave but ignorant defenders of the City of Cucumbers.”

[23]CHAPTER XXVI.

THE SHELLING OF SFAX.

My readers must suppose Mr. Galea watching anxiously the operations of the French from the deck of the ‘Beshir,’ and recording what took place in the journal to which I now return.

“July 5th, 1881, 4.10 P.M.—The ‘Chacal’ first began to bombard the town from a distance of about 2000 yards from the jetty, and the ‘Pique’ commenced firing an hour later. The Bimbashi is replying gallantly enough, but all his shot are falling short. Shells are being chiefly directed against the forts between the European faubourg and the shore. At last a shot from the town actually passed between the masts of the ‘Pique,’ and shortly afterwards both ships withdrew to the outer anchorage. As far as I can see, the shore battery is nearly dismantled and the pier much damaged. At Captain Tryon’s suggestion a large number of the fugitives are leaving for Malta in the S.S. ‘Peninsulaire,’ for there is literally nothing[24] more for them to live on here. The French fired fifty-four shots and the Tunisians seventeen this evening.

“July 6th.—At daybreak the ‘Alma’ and the ‘Reine Blanche’ (which had also arrived) got as close to the shore as they could, and at 5.45 A.M. began throwing shells to the west of the Arab town from a distance of two miles. The town made no reply, and firing ceased at 9 A.M. At noon all four ships joined in the bombardment and a brisk fire was continued for three hours. Only six shots (all falling short) were fired from the batteries, which the gunboats endeavoured to silence. Although 141 shells were thrown into the place, the enceinte facing the sea does not seem to be visibly damaged. About 4.30 P.M. the ‘Léopard’ arrived and joined the other gunboats at the inner anchorage.

“July 7th.—A desultory fire was maintained in the morning, and the injuries to the buildings can be seen clearly enough through a telescope. Later on, some steam-launches with marines on board approached the shore, but they were at once fired at from the forts and were obliged to retire. The ships then recommenced the bombardment, and when it grew dusk the launches once more went close to the town, but being received with volleys[25] of musketry again withdrew. It turns out that very few French troops are really here, and there can be no doubt that the assault is being carried on in the most unsatisfactory manner. The failures to effect a landing will not only encourage the Sfaxian Arabs, but those in the other coast towns, where the proceedings are being most anxiously watched with a view to decide on the position to be assumed.

“July 8th.—The French are again reconnoitring near the shore. From time to time a shot is fired, and the townspeople answer at intervals, but in an apparently hopeless manner.

“July 9th.—Sfax is one of the few places in the Mediterranean where the tide ebbs and flows. When the tide was full shortly after midnight, some Maltese, on behalf of the French, went close to the shore and cut out and brought away some boats suitable for use in landing the troops. Although the watch-dogs barked loudly, no one took any notice of them, and it seems as if the town could be taken by assault, or at any rate the guns spiked with impunity. All day the French have been collecting empty boats round their men-of-war, varying this occupation by firing an occasional shell. In the afternoon all the Tunisian troops were crowded into the ‘Manoubia’ and taken back to Tunis, to swell in[26] all probability the ranks of the malcontents around the capital.

“July 10th.—Not a shot was fired all day. The Italian gunboat ‘Cariddi’ arrived to see if anything was needed by the Italian fugitives. Another small French gunboat also came in.

“July 11th.—Nothing done to-day. The inaction is evidently encouraging the Arabs, and I am sorry to see the fortifications and barricades being repaired and strengthened with my esparto bales.

“July 12th.—This day was also passed in inactivity. I received the news from Gabes that the Arab captain of one of my barques has been arrested and sent a prisoner to Ali Ben Hlifa, because he had some barrels in his boat which were supposed to indicate an intention of obtaining supplies of water for the French.

“July 13th.—At last we have some hopes that matters are to be pushed vigorously to a conclusion. This morning the man-of-war ‘Galissonnière’ and another transport arrived. The former, at 2 P.M., threw a dozen shells into the town. In the evening the quarter near the gate dividing the Moorish from the European faubourg was seen to be on fire, but it was soon extinguished, or burnt itself out.

“July 14th.—In the forenoon six French men-of-war (the ‘Colbert,’ ‘Trident,’ ‘Marengo,’ ‘Surveillante,’[27] ‘Révanche,’ and ‘Friedland,’ together with a despatch boat (the ‘Desaix’), anchored in the roads. Salutes were fired, and much bunting was displayed during the day, on account of the Fête de la République. In the afternoon all the ironclads came as close as the depth of water would permit to the shore; but the attack was still postponed.

“July 15th.—The gunboats (‘Chacal,’ ‘Pique,’ ‘Léopard,’ ‘Gladiateur,’ and ‘Hyène’) shifted their position a little at dawn, and shortly after sunrise the French fleet, including even the ironclads four nautical miles away, began to shell the city and neighbourhood. There does not, however, seem to be any sign of landing. The delay has not only encouraged the Arabs here, but it has promoted the interests of the revolutionary party throughout the Regency. If a prompt and decisive blow had been struck at Sfax, the whole movement might have been nipped in the bud. The siege should never have begun until the French forces were mustered in sufficient strength and numbers to win a rapid and brilliant victory. Before noon to-day, 300 shots had fallen in different parts of the town. All the needy Maltese refugees are being furnished with supplies from H.M.S. ‘Monarch,’ and the commanders of the French frigates are following the example set by Captain Tryon. The bombardment was resumed[28] towards evening, and continued nearly all night; sleep became impossible from the constant booming of the cannon, and the sky seemed fairly a-blaze.

“July 16th.—After this terrible work of destruction had continued for twenty-four hours, the French troops landed in great force at break of day this morning, under cover of a heavy fire from the fleet. It required two hours’ fighting to gain possession of the fortifications, and even then the struggle was indefinitely prolonged in outlying houses and hamlets. By mid-day all was comparatively quiet. At the time of the landing, the esparto yards of two or three merchants were in flames; but our stores do not appear to have taken fire. Various estimates as to the loss on both sides have been made, but no two agree. Over a dozen French soldiers and marines, including an officer, have been interred in the Christian burial-ground, but others have shared undoubtedly a common grave with the Arabs in the trenches before the town. The resistance was as brave as it was hopeless, but no amount of personal courage can compensate for the use of weapons fit only for old metal-dealers or curiosity shops. In the narrow streets of the native town, house after house was only occupied after a desperate hand-to-hand conflict.”

· · · · · · · · · ·

[29]The sequel to the fall of Sfax I shall tell in the next chapter. There can be little question but that the delay in effecting the capture of the city to a great extent destroyed the moral effect of the achievement when it really did take place; instead of being the end and extinction of the insurrection, it became, as it were, the beginning of a race contest, the termination of which is still apparently in the future.

A humble poet has already sung the siege of Sfax. An honest tar, by name John Root, united on board H.M.S. “Monarch” the functions of able seaman and poetaster. On returning to Malta he published his “Bombardment of Sfax” in a leaflet, entitled “Thoughts and Facts from a Sailor’s Pen,” and if John’s quantities are somewhat rough and eccentric, his appreciations of what he saw are almost as correct as Mr. Galea’s. I quote a few verses, which tell quaintly enough in a few words the tale of the sad fate of Sfax:—

[31]CHAPTER XXVII.

LOOT.

Mr. Galea once more comes to my assistance and lends me his journal to write the story of the sad sequel to the capitulation of Sfax. My readers must remember that he was an eye-witness of most of the facts to which he speaks, and in justice to him I must say that his narrative is fully borne out and corroborated, not only by Mr. Consular-Agent Leonardi’s official reports, but by a mass of evidence tendered before the International Commission appointed to investigate the circumstances on the spot. If this were not the case, I would willingly pass over in silence the disagreeable subject of the sacking which followed the shelling, and which has given rise to so much heart-burning on all sides. Loot in the hour of victory was not first invented at Sfax, its occurrence is the rule rather than the exception in the annals of warfare, and as few countries can fairly throw a stone in the matter, I fail to see that it in any way[32] involves the national honour of France, or affects the reputation of anybody beyond those immediately concerned in the incident I am about to speak of. There can be no doubt whatever that the French soldiers who drove the Arabs out of Sfax on the 16th July 1881, followed up their triumph by an almost indiscriminate pillage of both the European and Arab quarters of the town. What was done happened in the face of day, and can neither be gainsaid or denied, and the subsequent attempts to minimise the transaction were at once unworthy and useless. Still more so is it censurable, to have postponed the relief of the sufferers indefinitely, and to endeavour to wring the compensation from the Arabs, who are nearly all the debtors of the persons who have been more or less ruined by the events in question. To my mind, these things are a far greater blemish to the good name of France than the excesses committed by her troops in the flush of success or the intoxication of conquest. With those few observations I return to Mr. Galea’s diary:—

“July 17th.—This morning I went on shore, accompanied by my assistant, Mr. Leadbetter, and the master of the British ship ‘Agnes.’ My first visit (after attending the funeral of some of the French soldiers who had been killed) was paid, naturally[33] enough, to my own business establishment. Everything movable had disappeared, and the yard was occupied by the French troops. Leaving the place, we next entered the European faubourg. Most of the houses were much damaged and knocked about by the shells, but on the pretext that some Arabs had fired from the dwelling of Mr. Gili (a Maltese merchant), an order had been given to break open the doors of every habitation in the quarter, and as soon as this was done a general pillage ensued. I was the unwilling witness of all that happened. The soldiers took or spoiled everything they could carry away, and broke or defaced what they were unable to move. None of the officers seemed at all disposed to interfere, and the whole business was a sad contrast to the measures taken by the insurgents to preserve our property, and was the more unjustifiable, as the Moorish quarter afforded a sufficiency of butin. The loss will of course fall on the British colony, and is a sad and unexpected aggravation of our privations during the past fortnight. Several liquor stores were emptied of their contents, and all I can say is that it is fortunate the Arabs did not resume the contest.

“July 18th.—The loot continues unabated. An order has been issued forbidding soldiers to enter houses unauthorised, but nobody attends to it, nor[34] is any attempt made to enforce it. I am, however, taking careful note of all that happens connected with this ruinous business. Caid Jelluli has not left the ‘Alma,’ but he has sent a letter, telling the Cadi and Mufti to come on board, at the head of a deputation of forty preceded by a white flag, to treat for terms, and informing them that unless they do so, the French will march into the gardens and attack everybody they come across.

“July 19th.—This morning I went to visit the great mosque. Its minaret is disabled, and it is turned into a barrack. I saw the soldiers cooking in various parts of it. Throughout the Moorish town the traces of the sack were painful to witness. What was not carried away from the shops in the bazaars, was thrown out into the streets. I saw title-deeds, bonds, and valuable papers lying amidst heaps of groceries and piles of stuffs. Although the former could never be replaced, and their loss might injure Moors and Christians alike, several of these miscellaneous collections of litter were deliberately set on fire. Valuable Arabic MSS. were torn up and their pages distributed as souvenirs of the siege—and, I presume, the sacking—of Sfax.

“July 20th.—The deputation demanded by Jelluli went out to the ‘Alma,’ and I believe all the Moors[35] who will bring their families are to be allowed to return. At any rate in the evening several of the native residents perambulated the Arab town calling out in a loud voice that all persons concealed were to come out, and that those who did so would be safe. Some eighty men were collected by this means, and then conveyed as prisoners on board the men-of-war. Three houses, the inmates of which declined to comply with the invitation thus given, were mined and blown up. It is only now that one can gradually obtain details of what really happened on the eventful 16th July. In addition to the struggle in the town, it appears that there was a regular battle fought in the country outside it. Many well-known Arab chiefs died fighting bravely; Ghasim Ben Shirouda, lately Hlifa of the Mitelit, his brother Sheikh Salah, Ali Ben Ardorri, son of a Hlifa, Sheikh Sesi Ben Muhamed, Sheikh Seyd Ben Muhamed, and Muhamed Ben Hdir were all shot down. In this engagement the Neffet were commanded by Ali Ben Hlifa, and the Beni Zid by Sherif-ed-Din. The Mitelit were led by Ardorri Ben Amor. These tribes alone took an actual part in the engagement.

“July 22d.—The mosque has been restored to the townspeople, but they seem in no hurry to take it. It will require a great deal of cleansing, and there[36] is an unexploded shell still in the top of the damaged minaret, which indisposes the muezzin to make the usual calls to prayer.

“July 24th.—The French fleet (except the ‘Alma’) left for Gabes, and H.M.S. ‘Monarch’ for Susa.

“July 25th.—We received to-day news of the occupation of Gabes yesterday. The inhabitants of the two villages near the shore, Jára and Menzel, have always hated each other, and generally differed in politics. In the present instance the former declared for the French, and the latter for the Holy War and the Prophet. After throwing some shells into Menzel, the French landed and occupied it. There was only a faint resistance from the insurgents amongst the palm-trees. Before evacuating the place the Arabs killed five Jews who had remained there. Later in the day the French troops left Menzel and encamped on the sea-shore, as they were not in sufficient force to resist an attack which was apparently meditated. No sooner had the French quitted it, than the Arabs returned, and set fire to most of the houses in the place. Menzel was therefore twice occupied by the insurgents and once by the French in a single day. The Kisla or castle of Gabes, an isolated fort between Menzel and the sea, surrendered in the morning. The officer in charge and his prisoner, the well-known[37] Alela Bizzai,[5] were received on board the men-of-war. No sooner had the French left the Kisla, than the Arabs rushed into it to seize the guns and powder. A few minutes after they entered it, a terrific explosion took place, and 300 persons at least were buried beneath the ruins or blown to pieces. The causes of this disaster are not precisely known, but it is supposed that one of the shells, which had been thrown into it prior to the exhibition of a white flag, suddenly burst, and ignited the gunpowder contained in a store beneath the fort. At the very same time (July 24th), 1000 French soldiers landed in the island of Jerba without exciting any hostile demonstration. The fort was surrendered at once, and the French flag hoisted upon it. Several Maltese families, who have for some weeks been living afloat, were now enabled to return to their homes.

“July 29th.—News reached Sfax to-day that Sheikh Khemoun, with the Bimbashi and some other persons, who had taken a prominent part in the defence[38] of the town, were proceeding to Tripoli overland. Caid Jelluli has now returned to the post from which he was ejected by the Bimbashi, but under a salute from the forts, and through a lane of French soldiers. He says he is resting, and cannot attend to public business. I am sorry to say that even now both wanton destruction of property and pillaging are still going on. As I am sure that this matter must sooner or later become the subject of much controversy, I shall write down some observations about it. In the first place, the care taken by the Arabs to protect property, after our departure, was a matter of public notoriety, as well as the draconic justice done by the Council of Forty. All houses occupied immediately after the landing by conscientious and respectable French officers were restored to their owners undisturbed, so much so that in one of them some money and jewellery were actually found on the table. A French doctor, who, as soon as he heard the fatal order to pillage, ran to his house and hung out a tricolour flag from the window, escaped without any loss, and the protection given him was also extended to a warehouse which happened to form the ground-floor of the building. Again, the telegraph office was not even touched, which would certainly not have been the case if the Arabs had commenced to destroy property[39] in the European quarter, nor would many stores of grain and oil (favourite object of Arab raids) have remained intact. On the 17th July, when we first landed, we all saw the soldiers with our own eyes entering shops and stores, and either looting or destroying everything they came across. As in the case of the Arab town, the streets were littered with heavy merchandise and papers of all descriptions, including business books, obligations, &c., and on the following day, to make matters worse, these heaps were carried out of the gates and burnt. Two days later, the notice of the colonel against pillage was issued, but it only diminished the looting and made it more secret. On the 21st July, Mr. Montebello, accompanied by Mr. Leadbetter, went to visit a shop belonging to the former, and found that, the door having been forced, a number of soldiers were helping themselves to its contents. A sentinel looked in and said nothing. An officer was sent for, but he confined his action to telling the sentinel not to let any more soldiers enter the place. Mr. Cardona made similar complaints as to what had happened in his warehouse. When Mr. Leadbetter examined one of our own houses on the 17th July, he found the strong-box, his desk, and books untouched. Returning two days later, he was surprised to see the safe thrown down and[40] forced, his desk rifled, and two soldiers playing with a valuable sewing-machine. He then endeavoured to prevent further damage by getting the doors sealed up, but on the 22d July he again found the seal broken and many other objects, including his clothes, gone. On the 30th July, ten days after the landing, I saw Mr. Consular-Agent Leonardi’s house being rummaged by soldiers, while at the same time their comrades had turned the square in front of the half-demolished Christian church into a loot bazaar. This traffic was witnessed by me from the first day of the occupation. Tunisian money was exchanged for napoleons at a loss of 40 per cent.; and I saw the Austrian Consul’s uniform sold for a mere trifle. The head of the custom-house informed me that the building was deliberately looted, notwithstanding his appeals to obtain its immunity as a public institution. When I asked him about this some days after, he was prudently reticent. There were many refugees on board the ‘Alma’ who saw the French writing letters on the valuable stamped paper, and when the marines exhibited their spoils, there was a pretty general chorus of ‘There are my books,’ ‘There are my clothes,’ and ‘There are my pictures,’ on the part of the victims. I have already described the measures taken by the Arabs to preserve order and[41] respect for the rights of property, even to the extent of insuring the continued payment of the Government dues, and it seems to me that if they had once commenced to pillage, everything would have been carried away into the interior. Another wanton waste caused by the French garrison is the indiscriminate destruction of everything which can possibly be burned. The item fuel seems not even to enter into the calculations of the French commissariat, and anything handy is at once chopped up to supply the want. The damage thus done has been enormous, whereas supplies of firewood are obtainable in the gardens quite close to the town. A great deal has been made of the discovery of some boxes belonging to M. Mattei in the house of Sheikh Khemoun, but they were unopened, untouched, and evidently brought there for fear, lest the mob might not be over-scrupulous in the matter of French property. Besides scores of eye-witnesses, there is other testimony as to nothing having happened before the landing. A Moor, by name Hàj Hmed Maala, found that a Maltese gardener and his large family, who lived in an outlying garden belonging to Mr. Gili, were in imminent danger, so he dressed them in Arab clothes and concealed them in his own country-house till he was able, after the capture of the place, to deliver[42] them up to Mr. Leonardi. This man (the Maltese gardener) says, that when the Arabs wished to pillage the European suburb, they were prevented from doing so by the action of the townspeople. The old bell-ringer of the Christian church lived all through the siege in a hole beneath the staircase of the tower, and was fed by the Arabs, who, he says, treated him kindly, and did no harm to anything. Their stories are fully confirmed by a number of Jews who lived on shore the whole time, and who were injured as regards neither their persons nor their property. In short, the Maltese colonists of Sfax have been the chief sufferers by the pillage of the town, committed in the manner I have described. Some of them have indeed lost their all; hardly one has escaped unscathed. As an eye-witness I have recorded what really happened in broad daylight and in the sight of hundreds of people. The only hope of the half-ruined British community is in the support which they feel sure their claims must inevitably receive from the English Government, and in the justice and equity of the International Commission which we hear is to inquire into the whole matter.”

· · · · · · · · · ·

One of the most disinterested witnesses of the sacking of Sfax is the poet before-the-mast, John[43] Root. I am not aware whether he was examined by the commissioners, but he writes with an evident knowledge of what took place:—

As I said before, the stamp of truth in John Root’s writings amply atones for his rugged metre and peculiar rhyme.

· · · · · · · · · ·

The International Commission at Sfax is now also a matter of history. It was composed of[44] Captain Count Marquesac of the “Reine Blanche,” President; General Sy Muhamed Jelluli; Captain Tryon, C.B., of H.M.S. “Monarch;” and Captain Conti of the Italian frigate, “Maria Pia.” After sitting for several weeks it was abruptly dissolved in October, because apparently the English and Italian members were unable to avoid the inevitable conclusion as to the authors of all the mischief. At the beginning of the present year, the Arabs of Sfax were compelled to contribute to a heavy “war indemnity.” Most of them were already the debtors of the much impoverished Maltese merchants, and the levy in question effectually prevented their satisfying the creditors for an indefinite period. In the result the Maltese first lost their goods, and then the possibility of obtaining the payment of their just debts. It is almost incredible, but it is nevertheless true, that notwithstanding the numerous sittings of the Commission, and the fact that the sums since collected have been very considerable, up to the present time not a single farthing of compensation has been paid to the unfortunate persons, who, after watching the shelling of their houses and shops for a fortnight from a distance, only returned to find them pillaged by the very people who professed not only to protect them, but to be the pioneers of a sentimental mission of political civilisation.

[45]Before going back to Northern Tunis I wish to bring the history of events on the southern coast down to the time of my own visit there at the end of November 1881. The French now occupied the town of Sfax, a spot on the sea-coast at Gabes, and the island of Jerba, but this was all. Outside these places the Arabs held undisputed sway, and no peaceful citizen could go beyond the French camps with impunity. The interval between August and November was passed chiefly in fruitless reconnaissances on the part of the French, and daring raids and night attacks on the side of the Arabs. As early as the 31st July it became again necessary to engage the Arabs in force at the village of Menzel. General Logerot’s arrival did not mend matters. The villagers of Jára, who had done nothing at all, and had “received the French as brothers,” were fined 20,000 francs, and ordered to induce their co-religionists at Menzel to submit to the French, under pain of a fresh bombardment and the destruction of the great Kouba of Sidi Bulbeba ou the neighbouring hill. As there was nothing left to bombard in Menzel, and as everything valuable had been taken away from the shrine of Sidi Bulbeba except his bones, the insurgents only laughed at the menaces. There were now over 3000 troops at Gabes, and the weather was oppressively[46] hot, yet they were unable to establish communication with the freshwater springs three miles off, and were compelled to drink the ooze of the muddy river, which was impregnated with magnesia and soon engendered dysentery and fever. All stragglers from the French camps were pitilessly massacred, and the sentries were often shot on guard. “On the night of the 10th August,” writes Mr. Galea, “the Arabs surprised the French camp, cut down the sentries and began killing the soldiers as they lay asleep. Before anything could be done they had rapidly retreated. The French admit a loss of twenty killed, but I have been told privately that it really exceeded that number.” Sickness broke out both at Sfax and Jerba, decimating in a terrible manner the garrison in the last-named island. Raid after raid took place around Sfax, but beyond shooting two obscure individuals on the 27th August on an equivocal charge preferred by the Vice-Consul Giannino, of calling out jihad, jihad (Holy War), very little was done. At times the insurgents approached so near to the town that they could be fired upon from the walls, and as soon as any tribe made terms with the French, it was immediately attacked by the insurgents. The “friendly Arabs” used to bring their dead and wounded as far as the ramparts, and cry in vain for help and assistance.[47] If it was General Winter who defeated the first Napoleon in Russia, it was certainly General Summer who now came to the assistance of the Arabs in Southern Tunis, with dysentery and typhoid fever as his aides-de-camp. While MM. Ferry and Saint-Hilaire were prudently consulting bourgeois susceptibilities by hastening on the elections to the French Chambers, while M. Roustan was obtaining concessions for his friends, and telegraphing reassuring platitudes to the Foreign Office, and while the Agence Havas was informing the French public that “our troops found the village abandoned, and returned to Susa, bringing with them a few hens, five cows, and five prisoners.” “It was a splendid operation,” it is added, “perfectly well conducted, and one which does the greatest honour to our young troops” (“Daily News,” October 3d, 1881),—the whole of Southern Tunis was abandoned to the most appalling anarchy and disorder, while the greater part of the northern part of the Regency was quickly preparing to follow suit.

[48]CHAPTER XXVIII.

ALARMS AT THE CAPITAL.

In the early days of July, M. Roustan succeeded in bringing to a luxurious villa at the Marsa a powerful and zealous ally. At his suggestion, and through French influence, Monseigneur Charles Martial Allemand Lavigérie, Archbishop of Algiers, superseded Monsignore Fra Fedele Suter, Bishop of Rosalia in partibus, as Apostolic Administrator of Carthage and Tunis. Archbishop Lavigérie was essentially a prélat de combat, and his militant missionaries have been for several years gradually gaining influence in Algeria, Tunis, and even Tripoli. The French Government could not possibly have obtained more useful and uncompromising auxiliaries than these white-robed and red-capped frères d’Afrique, who, under the harmless garb of theology, pill-making, and tooth-drawing, are preparing the path for French conquests in the unexplored regions of the Sahara. The practical head of an eminently practical confraternity,[49] Archbishop Lavigérie had been initiated, by a prolonged residence at the Vatican, into the useful art of combining doctrine and politics, and came to Tunis fully determined to acquire a lion’s share in the powers of the Protectorate. Such was the enthusiasm with which he was endowed, that three years before, he had succeeded in reducing even the crown of martyrdom to the matter-of-fact condition of a marketable commodity. In the quarterly issue of the Bulletin de l’Œuvre de Saint-Augustin for January 1878, I find him publishing the following notice: “Adoptions of Missionaries.—Our associates are aware that by paying the sum of 800 francs, they can support for a year a missionary in Africa. They become in this manner partners in his works and meritorious actions, as well as in his crown of martyrdom, as happened in the case of the charitable benefactors, who adopted the three missionaries who died for the faith on their road to Timbuctoo.” While the Pope is sending a Cardinal’s hat to the pioneer of French influence and martyrdom-by-proxy in North Africa, the Pacha of Tripoli is threatened with an incursion of French cavalry (not indeed to punish the Khamírs), but to chastise the Towaregs on account of the untimely fate of three other missionaries, who, notwithstanding the[50] most explicit warnings, insisted on travelling from Ghadámes to Ghát. This peculiar feature of French policy was clearly foreshadowed and described in the correspondence of Sir Thomas Reade nearly forty years ago; and to such an extent has it been now carried that the Bey, the French Resident, and the Cardinal Archbishop may, at the present moment, be correctly described as the governing triumvirate of that portion of the Regency of Tunis which is not in the hands of the insurgents. Before the summer heat had fairly set in, M. Roustan had rewarded his friends, harassed his enemies, and reassured M. Saint-Hilaire; but the unexpected outbreak, in the early days of July, of a widespread revolution throughout the length and breadth of the Regency, entailed a very serious interruption in his plans, as well as in those of his political superiors.

First came the risings at Sfax, Gabes, and Jerba, of which I have already spoken at length. On the 4th July, information reached Tunis that the Arabs near Monastir had already defied the Bey’s authority, and had murdered three Europeans in a neighbouring village. The same evening the French Captain Mattei was assassinated close to the Bey’s palace and the Manouba camp. His murderer managed to escape, but an innocent Arab[51] paid the penalty of the crime. The unfortunate boy, who was shot by mistake, is buried in the ditch near which he fell, and his mother is a raving lunatic in the Arab madhouse. The complications, however, did not seem to disturb at once the unlimited power wielded by M. Roustan. It was just now that he interfered to prevent the sale of landed property by an English subject to French bankers, because his consent was not previously obtained to the transaction. The matter was denied at the time, but the fact rests on the testimony of M. Valensi, the representative of the legendary French colony, and the zealous framer of chronic addresses in favour of M. Roustan, and who himself telegraphed to this effect to the would-be purchaser.

Every day the news of some fresh accession to the ranks of the rebels reached the Bardo. On the 18th July, while the Bey was listening to the details of the capture of his “faithful town of Sfax,” a band of 800 men belonging to the Zlass tribe, carried off 2000 of the royal camels from their pasture-lands, not two miles from the Manouba camp and the Kasr-es-Said gardens. A posse of Arab cavalry entered Kairwán and collected vi et armis the public taxes, while another party invaded the Enfida and settled for themselves the[52] vexed question of Hanafee and Melaki, by driving everybody out of it. Raids on the farms surrounding Tunis now became of daily occurrence, and at this juncture the Prime Minister Mustapha hurried back to Tunis as fast as a despatch-boat could carry him. But the position grew daily more and more serious; the Tunisian soldiers who had cheered in the very presence of the French at each halting shot fired by the Bimbashi of Sfax, came back to their quarters at the capital only to desert. The Bey was now urged to adopt the very remedy which had been ridiculed by M. Roustan four months before. He was told to call out the native army and form “a camp,” but his power and influence were both hopelessly ruined, and he was regarded as a traitor and a coward by every honest man amongst his subjects. Even while M. Roustan and General Logerot were elaborating their plans of a Tunisian expedition, hundreds of the rough Arab soldiers were taking their road southwards, calling out to every one they met, “We will fight for Ali Ben Hlifa and the Sultan.” The truth could no longer be ignored; revolution and anarchy now prevailed both in Southern and Central Tunis. French troops were every day returning to the Regency, but the heat still favoured the Arabs. On the 24th July half the Bey’s bodyguard was[53] missing, and the farm of Mustapha between Mater and Bizerta in Northern Tunis was pillaged by Arab cavalry. Under these circumstances Sy Ali Bey, now civilised and friendly, found the task of organising a native force one of peculiar delicacy and difficulty. The soldiers, who had not as yet actually deserted, were far more likely to keep him as a hostage or convey him against his will to the tents of Ali Ben Hlifa, than to join him in attacking their comrades or co-religionists, for whose proceedings they entertained a lively sympathy.

On the 26th July a band of insurgents could be seen approaching Rades, which, as I have said before, is equally visible from Tunis and Goletta. A panic seized on the inhabitants of both places; business was suspended, shops closed, boats hired, and a general stampede prepared. The Bey ordered the bridge between Goletta and Rades to be broken down, and the passage to be guarded by artillery. A little later in the day the news came that a well-known Greek gentleman had been murdered in an outlying farm. The excitement then reached its culminating point, and an Arab attack was really apprehended. People in Tunis decided to fly to Goletta, and persons in Goletta determined to take refuge in Tunis. A crowd of Tunisian fugitives arrived by train at Goletta, but[54] only to meet another mob of refugees waiting impatiently to take the return train to Tunis. The meeting of the two crowds formed a very amusing tableau, and the more so because a moment’s reflection must show that any attempt to invade two walled towns by the Arabs of the interior would be wholly out of the question.

Up to the present time the Tunisian difficulty, as far as Europe was concerned, had only affected two platonic overthrows of the Italian Cabinet: in France everything had gone smoothly, and the Treaty of Kasr-es-Said had been ratified almost by acclamation. The tide, however, had now turned, and MM. Ferry and Saint-Hilaire knew it; the expedition, shorn of its tinsel and trappings, was becoming day by day more unpopular, and the opinion was fast gaining ground that the French Protectorate over Tunis was a white elephant of a very costly and unmanageable character. The time was at hand when Tunis was to become an unmistakable factor in the politics of France, and to make matters worse, Bou Amema was threatening simultaneously a very serious disturbance in Algeria. The general elections were already fixed for the 14th September, but if things meanwhile grew worse in Tunis and Algeria a disaster might pretty confidently be anticipated. It was therefore[55] decided to hasten the elections by a full month. “If in September,” wrote M. De Blowitz, now completely disenchanted, on the 27th July, “the country were confronted with a serious African campaign, the elections might be seriously compromised, and a formidable argument afforded to the Opposition. Consequently, notwithstanding all prior arrangements, it was decided that the elections should be held without delay, before any African troubles had time to break out.”

On the very same day, the town of Hammamet, fifty miles from Tunis, underwent an “African trouble” of a very disagreeable nature. It was attacked by Arab horsemen, who carried all the cattle belonging to its inhabitants away into the mountains, and pillaged a house belonging to the British Consular Agent, Mr. Cacchia, who was doomed to be one of the greatest losers by the insurrection. The fast of Ramadan now began, but the Bey reflected on the possibility of sharing the fate of his camels, and decided, for the first time in his reign, to spend the month in the comparative security of the pavilion on piles at Goletta. Up to this time only 400 irregular militia could be collected to form the nucleus of Sy Ali Bey’s contingent, and the regular army was reduced to about fourscore men. On the last day[56] of July things reached such a pitch, that twelve soldiers had to be sent from Tunis to replace those who had deserted from the guard which protected the pavilion on piles. A few hours after their arrival they also deserted, together with one of their officers.

[57]CHAPTER XXIX.

AUGUST 1881.

The position of affairs at the beginning of August was singularly unfortunate. Fever and dysentery now began to make sad havoc amongst the French troops, almost wholly unaccustomed to the tropical heat of a Tunisian autumn; raids on the homesteads almost in sight of the walls of Tunis increased and multiplied, and the Bey was making feeble efforts to raise a small force to send to Testour “to protect the French railway,” and to borrow the money wherewithal to pay the cost of it. On the 2d of August, an unbroken Moslem supremacy of three centuries terminated in the landing of two battalions of French troops at Goletta, and even the presence of the Bey’s band failed to attenuate the real state of the case in the minds of the Arabs. Just after the French had passed through the streets, the steamer from the coast arrived, bringing on it 300 of the Tunisian soldiers, who had lately deserted, and who had been[58] persuaded to return. As soon as they saw what had happened they became very excited, and openly said they would again desert, as they could not be wanted if the Bey called in French troops to “protect” him. From this time French troops began to land in great numbers at Goletta, and on the 6th August, 2000 men encamped at Hammam-el-Lif on the other side of the bay, to remain there till the arrangements for the great Kairwán expedition, which was to calm all parties, including the French electors, were completed. Meanwhile the insurrectionary movement in Northern Tunis grew apace. The insurgent Arabs made a night attack on Medjez-el-Bab, ill-treated the townspeople, carried away their cattle, destroyed a portion of the subsidised French railway, and tore down the telegraph wire and posts. More pressure was now put on the Bey to send his “army” towards Medjez and Testour, but his “protectors” would not come to his aid, and he only succeeded (in spite of the presence of several French financial houses in the country) in scraping together a loan of £37,000, at an annual interest of fourteen per cent.

At last 500 soldiers belonging to the irregular Tunisian militia were sent one march forward towards Testour, but over 200 deserted en route.[59] The 300 men who came back to Goletta from Susa likewise disappeared.

About the middle of the month the Arabs around Susa, and between Susa and Kairwán, assumed a menacing attitude, and many of the tribes between Tunis and Algeria prepared to rise. To add to the difficulties of the situation the telegraph wires were again and again cut. Although reinforcements continued to arrive, and General Saussier came on the 13th August to study the campaign, now become inevitable, no movement could be executed to check the depredations of the insurgents. Even the very day after the Commander-in-chief’s arrival, and almost in his presence, fifty of the heavily chained convicts, confined in a pestilential dungeon beneath the Goletta fort, contrived to break their fetters, and about dusk rushed into the street. A cry was at once raised that the Bedouins had entered the place; shops and houses were barricaded, and the panic palpably extended to the French officers and soldiers, who, in the cool of the evening, were discussing their absinthe or vermouth before the different cafés. The prisoners, although armed with guns, pistols, and bayonets, hurt no one, and quickly gained the open country. As soon as the alarm subsided, everybody was becomingly valorous after the event, but as the Bey did not wish any[60] French soldiers to join in the pursuit, only a few Arab irregulars, armed apparently with poles and sticks, made a vain and burlesque attempt to capture the fugitives.

The Austrian Consul-General, Herr Theodorovich, happened to meet the runaways outside Goletta, and fled precipitately to the French camp near Carthage, bringing the alarming news of the “taking of Goletta by the insurgents.” The soldiers had already been got under arms, when the true state of the case transpired, but it was thought necessary to provide the representative of Austria with a suitable guard to accompany him back to Goletta. This serio-comic incident indicates sufficiently the extent of the insurrectionary movement, even close to the capital itself.

The deserters from the Tunisian army seem to have nearly all joined the insurgents threatening Susa, and the Governor, General Bacouch, now acknowledged that his authority outside the town walls was gone. On the evening of the 14th August, a Tripolitan Arab appeared in the streets of Susa with a drawn sword, and with the ominous cry of “jihad! jihad!” stabbed to death an unoffending old Maltese tradesman in his own shop. The shouts of the murderer had been echoed by others, and there is no doubt but that the accidental[61] arrival of H.M.S. “Monarch” and the calm presence of mind of Captain Tryon, alone saved the European colony from some terrible disaster. Captain Tryon at once prepared to land his marines, but before this could be done, Sy Muhamed Bacouch had succeeded in restoring order. The assassin was sent to Tunis and subsequently hung.

Having arranged the plan of the Kairwán crusade, General Saussier returned to Algeria on the 19th August, leaving Arab anarchy rampant and unchecked, until cooler weather should allow the realisation of his projects. Urgent letters from the Governor of Kairwán, however, now rendered some kind of immediate movement necessary. About 2000 Tunisian irregulars were collected; and on the 20th August these started in the direction of Testour, commanded by Ali Bey and the Generals Ahmed Zerouck and Ali Ben Tourkia. Two French columns of 1500 each started about the same time for Hammamet and Zaghouán. Little progress could be made by the Tunisian force, as all the baggage camels had been stolen in the great razzia of the Zlass tribe in July.

The town of Susa was now practically in a state of siege. A Maltese, who went to his garden outside the walls, was at once shot dead, and as the[62] villagers and tribesmen had agreed to join in an attack on the town, the gates could only be opened at intervals. The Arabs speedily contrived to cut off communication between the Hammamet and Zaghouán columns and Tunis; several convoys of carts were intercepted and robbed, and the drivers escaped with the loss of their property and horses. A Maltese courier was killed close to Zaghouán, and a native guard who accompanied him was also shot. The relatives of the latter were carrying away the body, when some more carts, now escorted by French troops, appeared. Unluckily enough the mourners were mistaken for marauders, and shot by the soldiers before any explanation could be given.

The Hammamet column under Colonel Corréard now sustained a severe check, and was finally obliged to fall back towards Hamman-el-Lif. This was, perhaps, the only success gained by the Arabs in a fair fight during the whole campaign, and they certainly made the most of it. Ali Bey seemed to be unable to quit the vicinity of the capital, and to add to the perplexities occasioned by the equivocal attitude of his “irregulars,” he received a letter from Ali Ben Hlifa, saying that he would be attacked by the Arabs as an “infidel and a Frenchman” at the first opportunity.

[63]CHAPTER XXX.

THE COMING CAMPAIGN.