CHAPTER I.

ANTIQUITY OF ENGRAVING.

Engraving—the word explained—the art

defined—distinction between engraving on copper and on

wood—early practice of the art of impressing characters by means

of stamps instanced in babylonian bricks; fragments of egyptian and

etruscan earthenware; roman lamps, tiles, and amphoræ—the

cauterium or brand—principle of stencilling known to the

romans—royal signatures thus affixed—practice of stamping

monograms on documents in the middle ages—notarial stamps—

merchants’-marks—coins, seals, and sepulchral

brasses—examination of mr. ottley’s opinions concerning the origin

of the art of wood engraving in europe, and its early practice by two

wonderful children, the cunio.

s

few persons know, even amongst those who profess to be admirers of the

art of Wood Engraving, by what means its effects, as seen in books and

single impressions, are produced, and as a yet smaller number understand

in what manner it specifically differs in its procedure from the art of

engraving on copper or steel, it appears necessary, before entering into

any historic detail of its progress, to premise a few observations

explanatory of the word Engraving in

its general acceptation, and more particularly descriptive of that

branch of the art which several persons call Xylography; but which is as

clearly expressed, and much more generally understood, by the term Wood Engraving.

s

few persons know, even amongst those who profess to be admirers of the

art of Wood Engraving, by what means its effects, as seen in books and

single impressions, are produced, and as a yet smaller number understand

in what manner it specifically differs in its procedure from the art of

engraving on copper or steel, it appears necessary, before entering into

any historic detail of its progress, to premise a few observations

explanatory of the word Engraving in

its general acceptation, and more particularly descriptive of that

branch of the art which several persons call Xylography; but which is as

clearly expressed, and much more generally understood, by the term Wood Engraving.

The primary meaning of the verb “to engrave” is defined by Dr.

Johnson, “to picture by incisions in any matter;” and he derives it from

2

the French “engraver.” The great lexicographer is not, however,

quite correct in his derivation; for the French do not use the verb

“engraver” in the sense of “to engrave,” but to signify a ship or a boat

being embedded in sand or mud so that she cannot float. The French

synonym of the English verb “to engrave,” is “graver;” and its root is

to be found in the Greek γράφω (grapho, I cut), which, with its

compound ἐπιγράφω, according to Martorelli, as cited by Von

Murr,I.1 is always used by Homer to express cutting, incision,

or wounding; but never to express writing by the superficial tracing of

characters with a reed or pen. From the circumstance of laws, in the

early ages of Grecian history, being cut or engraved on wood, the word

γράφω

came to be used in the sense of, “I sanction, or I pass a law;” and

when, in the progress of society and the improvement of art, letters,

instead of being cut on wood, were indented by means of a skewer-shaped

instrument (stylus) on wax spread on tablets of wood or ivory, or

written by means of a pen or reed on papyrus or on parchment, the word

γράφω,

which in its primitive meaning signified “to cut,” became expressive of

writing generally.

From γράφω is derived the Latin scribo,I.2 “I write;” and

it is worthy of observation, that “to scrive,”—most

probably from scribo,—signifies, in our own language, to

cut numerals or other characters on timber with a tool called a

scrive: the word thus passing, as it were, through a circle of

various meanings and in different languages, and at last returning to

its original signification.

Under the general term Sculpture—the root of which is to be found in

the Latin verb sculpo, “I cut”—have been classed

copper-plate engraving, wood engraving, gem engraving, and carving, as

well as the art of the statuary or figure-cutter in marble, to which art

the word sculpture is now more strictly applied, each of those

arts requiring in its process the act of cutting of one kind or

other. In the German language, which seldom borrows its terms of art

from other languages, the various modes of cutting in sculpture, in

copper-plate engraving, and in engraving on wood, are indicated in the

name expressive of the operator or artist. The sculptor is named a

Bildhauer, from Bild, a statue, and hauen, to hew,

indicating the operation of cutting with a mallet and chisel; the

copper-plate engraver is called a Kupfer-stecher, from

Kupfer, copper, and stechen, to dig or cut with the point;

and the wood engraver is a Holzschneider, from Holz, wood,

and schneiden, to cut with the edge.

It is to be observed, that though both the copper-plate engraver and

3

the wood engraver may be said to cut in a certain sense, as well

as the sculptor and the carver, they have to execute their work

reversed,—that is, contrary to the manner in which

impressions from their plates or blocks are seen; and that in copying a

painting or a drawing, it requires to be reversely transferred,—a

disadvantage under which the sculptor and the carver do not labour, as

they copy their models or subjects direct.

Engraving, as the word is at the

present time popularly used, and considered in its relation to the

pictorial art, may be defined to be—“The art of representing

objects on metallic substances, or on wood, expressed by lines and

points produced by means of corrosion, incision, or excision, for the

purpose of their being impressed on paper by means of ink or other

colouring matter.”

The impressions obtained from engraved plates of metal or from

blocks of wood are commonly called engravings, and sometimes

prints. Formerly the word cutsI.3 was applied indiscriminately to

impressions, either from metal or wood; but at present it is more

strictly confined to the productions of the wood engraver. Impressions

from copper-plates only are properly called plates; though it is

not unusual for persons who profess to review productions of art, to

speak of a book containing, perhaps, a number of indifferent

woodcuts, as “a work embellished with a profusion of the most

charming plates on wood;” thus affording to every one who is in the

least acquainted with the art at once a specimen of their taste and

their knowledge.

Independent of the difference of the material on which copper-plate

engraving and wood engraving are executed, the grand distinction between

the two arts is, that the engraver on copper corrodes by means of

aqua-fortis, or cuts out with the burin or dry-point, the lines,

stipplings, and hatchings from which his impression is to be produced;

while, on the contrary, the wood engraver effects his purpose by cutting

away those parts which are to appear white or colourless, thus leaving

the lines which produce the impression prominent.

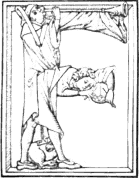

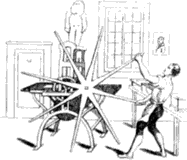

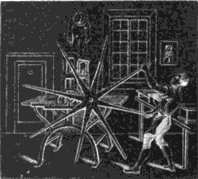

In printing from a copper or steel plate, which is previously warmed

by being placed above a charcoal fire, the ink or colouring matter is

rubbed into the lines or incisions by means of a kind of ball formed of

woollen cloth; and when the lines are thus sufficiently charged with

ink, the surface of the plate is first wiped with a piece of rag, and is

then further cleaned and smoothed by the fleshy part of the palm of the

hand, slightly touched with whitening, being once or twice passed rather

quickly and lightly over it. The plate thus prepared is covered with the

paper intended to receive the engraving, and is subjected to the action

of

4

the rolling or copper-plate printer’s press; and the impression is

obtained by the paper being pressed into the inked incisions.

As the lines of an engraved block of wood are prominent or in relief,

while those of a copper-plate are, as has been previously explained,

intagliate or hollowed, the mode of taking an impression from the

former is precisely the reverse of that which has just been described.

The usual mode of taking impressions from an engraved block of wood is

by means of the printing-press, either from the block separately, or

wedged up in a chase with types. The block is inked by being beat

with a roller on the surface, in the same manner as type; and the paper

being turned over upon it from the tympan, it is then run in

under the platen; which being acted on by the lever, presses the

paper on to the raised lines of the block, and thus produces the

impression. Impressions from wood are thus obtained by the

on-pression of the paper against the raised or prominent lines;

while impressions from copper-plates are obtained by the

in-pression of the paper into hollowed ones. In consequence of

this difference in the process, the inked lines impressed on paper from

a copper-plate appear prominent when viewed direct; while the lines

communicated from an engraved wood-block are indented in the front of

the impression, and appear raised at the back.

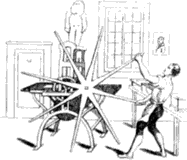

PRINTED FROM A WOOD-BLOCK.

PRINTED FROM A COPPER-PLATE.

The above impressions—the one from a wood-block, and the other

from an etched copper-plate—will perhaps render what has been

already said, explanatory of the difference between copper-plate

printing from hollowed lines, and surface printing by means of

the common press from prominent lines, still more intelligible. The

subject is a representation of the copper-plate or rolling press.

Both the preceding impressions are produced in the same manner by

means of the common printing-press. One is from wood; the other, where

the white lines are seen on a black ground, is from copper;—the

hollowed lines, which in copper-plate printing yield the impression,

5

receiving no ink from the printer’s balls or rollers; while the surface,

which in copper-plate printing is wiped clean after the lines are filled

with ink, is perfectly covered with it. It is, therefore, evident, that

if this etching were printed in the same manner as other copper-plates,

the impression would be a fac-simile of the one from wood. It has been

judged necessary to be thus minute in explaining the difference between

copper-plate and wood engraving, as the difference in the mode of

obtaining impressions does not appear to have been previously pointed

out with sufficient precision.

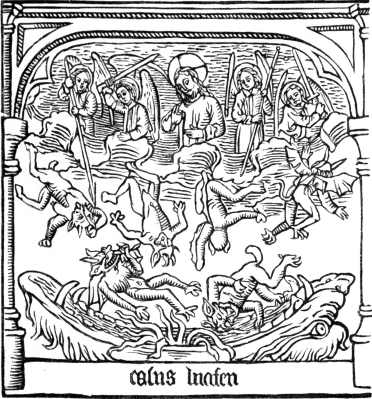

As it does not come within the scope of the present work to inquire

into the origin of sculpture generally, I shall not here venture to

give an opinion whether the art was invented by Adam or his good angel Raziel, or whether it was introduced at a subsequent

period by Tubal-Cain, Noah, Trismegistus,

Zoroaster, or Moses. Those who feel interested in such remote

speculations will find the “authorities” in the second chapter of

Evelyn’s “Sculptura.”

Without, therefore, inquiring when or by whom the art of engraving

for the purpose of producing impressions was invented, I shall

endeavour to show that such an art, however rude, was known at a very

early period; and that it continued to be practised in Europe, though to

a very limited extent, from an age anterior to the birth of Christ, to

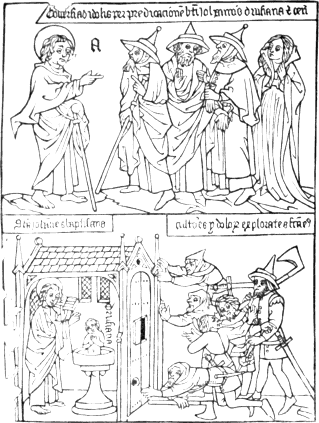

the year 1400. In the fifteenth century, its principles appear to have

been more generally applied;—first, to the simple cutting of

figures on wood for the purpose of being impressed on paper; next, to

cutting figures and explanatory text on the same block, and then entire

pages of text without figures, till the “ARS

GRAPHICA ET IMPRESSORIA” attained its perfection in the discovery

of PRINTING by means of movable fusile

types.I.4

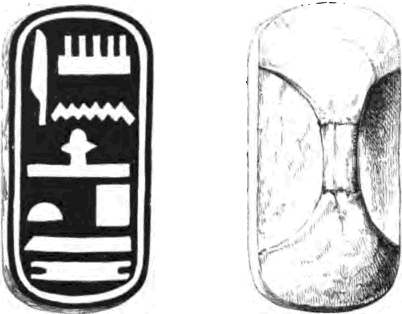

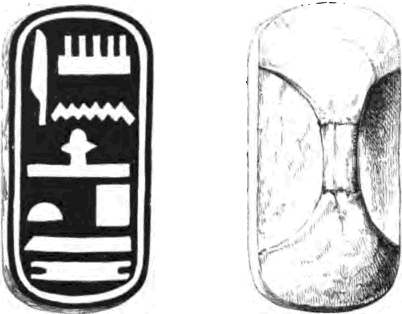

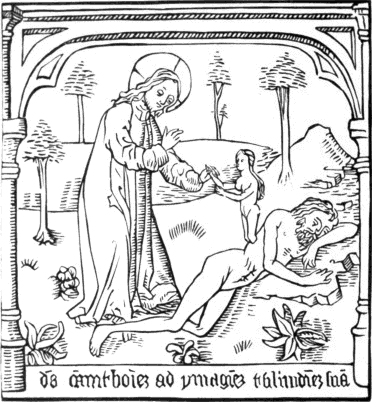

At a very early period stamps of wood, having hieroglyphic characters

engraved on them, were used in Egypt for the purpose of producing

impressions on bricks, and on other articles made of clay. This fact,

which might have been inferred from the ancient bricks and fragments of

earthenware containing characters evidently communicated by means of a

stamp, has been established by the discovery of several of those wooden

stamps, of undoubted antiquity, in the tombs at Thebes, Meroe, and other

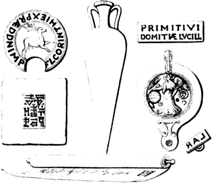

places. The following cuts represent the face and the back of one of the

most perfect of those stamps, which was found in a tomb at Thebes, and

has recently been brought to this country by Edward William Lane, Esq.I.5

The original stamp is made of the same kind of wood as the

6

mummy chests, and has an arched handle at the back, cut out of the same

piece of wood as the face. It is of an oblong figure, with the ends

rounded off; five inches long, two inches and a quarter broad, and half

an inch thick. The hieroglyphic characters on its face are rudely cut in

intaglio, so that their impression on clay would be in relief;

and if printed in the same manner as the preceding copy, would present

the same appearance,—that is, the characters which are cut into

the wood, would appear white on a black ground. The phonetic power of

the hieroglyphics on the face of the stamp may be represented

respectively by the letters, A, M, N, F, T,

P, T, H, M; and the vowels being supplied, as in reading

Hebrew without points, we have the words, “Amonophtep,

Thmei-mai,”—“Amonoph, beloved of truth.”I.6 The name is supposed to be

that of Amonoph or Amenoph the First, the second king of the eighteenth

dynasty, who, according to the best authorities, was contemporary with

Moses, and reigned in Egypt previous to the departure of the Israelites.

There are two ancient Egyptian bricks in the British Museum on which the

impression of a similar stamp is quite distinct; and there are also

several articles of burnt clay, of an elongated conical figure, and

about nine inches long, which have their broader extremities impressed

with hieroglyphics in a similar manner. There is also in the same

collection a wooden

7

stamp, of a larger size than that belonging to Mr. Lane, but not in so

perfect a condition. Several ancient Etruscan terra-cottas and fragments

of earthenware have been discovered, on which there are alphabetic

characters, evidently impressed from a stamp, which was probably of

wood. In the time of Pliny terra-cottas thus impressed were called

Typi.

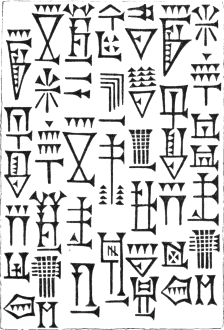

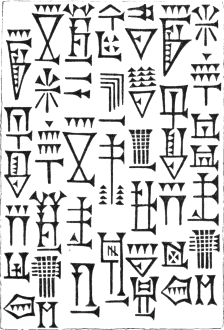

In the British Museum are several bricks which have been found on the

site of ancient Babylon. They are larger than our bricks, and somewhat

different in form, being about twelve inches square and three inches

thick. They appear to have been made of a kind of muddy clay with which

portions of chopped straw have been mixed to cause it to bind; and their

general appearance and colour, which is like that of a common brick

before it is burnt, plainly enough indicate that they have not been

hardened by fire, but by exposure to the sun. About the middle of their

broadest surface, they are impressed with certain characters which have

evidently been indented when the brick was in a soft state. The

characters are indented,—that is, they are such as would be

produced by pressing a wood-block with raised lines upon a mass of soft

clay; and were such a block printed on paper in the usual manner of

wood-cuts, the impression

8

would be similar to the preceding one, which has been copied, on a

reduced scale, from one of the bricks above noticed. The characters have

been variously described as cuneiform or wedge-shaped, arrow-headed,

javelin-headed, or nail-headed; but their meaning has not hitherto been

deciphered.

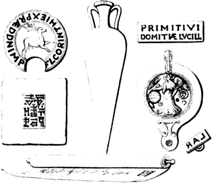

Amphoræ, lamps, tiles, and various domestic utensils, formed of clay,

and of Roman workmanship, are found impressed with letters, which in

some cases are supposed to denote the potter’s name, and in others the

contents of the vessel, or the name of the owner. On the tiles,—of

which there are specimens in the British Museum,—the letters are

commonly inscribed in a circle, and appear raised; thus showing that the

stamp had been hollowed, or engraved in intaglio, in a manner similar to

a wooden butter-print. In a book entitled “Ælia Lælia Crispis non nata

resurgens,” by C. C. Malvasia, 4to. Bologna, 1683, are several

engravings on wood of such tiles, found in the neighbourhood of Rome,

and communicated to the author by Fabretti, who, in the seventh chapter

of his own work,I.7 has given some account of the “figlinarum

signa,”—the stamps of the ancient potters and tile-makers.

The stamp from which the following cut has been copied is preserved

in the British Museum. It is of brass, and the letters are in relief and

reversed; so that if it were inked from a printer’s ball and stamped on

paper, an impression would be produced precisely the same as that which

is here given.

It would be difficult now to ascertain why this stamp should be

marked with the word Lar, which

signifies a household god, or the image of the supposed tutelary genius

of a house; but, without much stretch of imagination, we may easily

conceive how appropriate such an inscription would be impressed on an

amphora or large wine-vessel, sealed and set apart on the birth of an

heir, and to be kept sacred—inviolate as the household

gods—till the young Roman assumed the “toga virilis,” or arrived

at years of maturity. That vessels containing wine were kept for many

years, we learn from Horace and Petronius;I.8

9

——Prome reconditum,

Lyde, strenua, Cæcubum,

Munitæque adhibe vim sapientiæ.

Inclinare meridiem

Sentis: ac veluti stet volucris dies,

Parcis deripere horreo

Cessantem Bibuli Consulis amphoram.

Carmin. lib. III. xxviii.

“Quickly produce, Lyde, the hoarded Cæcuban, and make an attack upon

wisdom, ever on her guard. You perceive the noontide is on its decline;

and yet, as if the fleeting day stood still, you delay to bring out of

the store-house the loitering cask, (that bears its date) from the Consul

Bibulus.”—Smart’s Translation.

Mr. Ottley, in his “Inquiry into the Origin and Early History of

Engraving,” pages 57 and 58, makes a distinction between

impression where the characters impressed are produced by

“a change of form”—meaning where they are either

indented in the substance impressed, or raised upon it in

relief—and impression where the characters are produced by

colour; and requires evidence that the ancients ever used stamps

“charged with ink or some other tint, for the purpose of stamping paper,

parchment, or other substances, little or not at all capable of

indentation.”

It certainly would be very difficult, if not impossible, to produce a

piece of paper, parchment, or cloth of the age of the Romans impressed

with letters in ink or other colouring matter; but the existence of such

stamps as the preceding,—and there are others in the British

Museum of the same kind, containing more letters and of a smaller

size,—renders it very probable that they were used for the purpose

of marking cloth, paper, and similar substances, with ink, as well as

for being impressed in wax or clay.

Von Murr, in an article in his Journal, on the Art of Wood Engraving,

gives a copy from a similar bronze stamp, in Praun’s Museum, with the

inscription “Galliani,” which he

considers as most distinctly proving that the Romans had nearly arrived

at the arts of wood engraving and book printing. He adds: “Letters cut

on wood they certainly had, and very likely grotesques and figures also,

the hint of which their artists might readily obtain from the coloured

stuffs which were frequently presented by Indian ambassadors to the

emperors.”I.9

At page 90 of Singer’s “Researches into the History of Playing-Cards”

are impressions copied from stamps similar to the preceding;

10

which stamps the author considers as affording “examples of such a near

approach to the art of printing as first practised, that it is truly

extraordinary there is no remaining evidence of its having been

exercised by them;—unless we suppose that they were acquainted

with it, and did not choose to adopt it from reasons of state policy.”

It is just as extraordinary that the Greek who employed the expansive

force of steam in the Ælopile to blow the fire did not invent Newcomen’s

engine;—unless, indeed, we suppose that the construction of such

an engine was perfectly known at Syracuse, but that the government there

did not choose to adopt it from motives of “state policy.” It was not,

however, a reason of “state policy” which caused the Roman cavalry

to ride without stirrups, or the windows of the palace of Augustus to

remain unglazed.

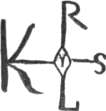

The following impressions are also copied from two other brass

stamps, preserved in the collection of Roman antiquities in the British

Museum.

As the letters in the originals are hollowed or cut into the metal,

they would, if impressed on clay or soft wax, appear raised or in

relief; and if inked and impressed on paper or on white cloth, they

would present the same appearance that they do here—white on a

black ground. Not being able to explain the letters on these stamps,

further than that the first may be the dative case of a proper name

Ovirillius, and indicate that property so marked belonged to such a

person, I leave them, as Francis Moore, physician, leaves the

hieroglyphic in his Almanack,—“to time and the curious to

construe.”

11

Lambinet, in his “Recherches sur l’Origine de l’Imprimerie,” gives an

account of two stone stamps of the form of small tablets, the letters of

which were cut in intaglio and reverse, similar to the two of

which impressions are above given. They were found in 1808, near the

village of Nais, in the department of the Meuse; and as the letters,

being in reverse, could not be made out, the owner of the tablets sent

them to the Celtic Society of Paris, where M. Dulaure, to whose

examination they were submitted, was of opinion that they were a kind of

matrices or hollow stamps, intended to be applied to soft substances or

such as were in a state of fusion. He thought they were stamps for

vessels containing medical compositions; and if his reading of one of

the inscriptions be correct, the practice of stamping the name of a

quack and the nature of his remedy, in relief on the side of an

ointment-pot or a bottle, is of high antiquity. The letters

Q. JUN. TAURI. ANODY.

NUM. AD OMN. LIPP.

M. Dulaure explains thus: Quinti Junii Tauridi anodynum ad omnes

lippas;I.10 an inscription which is almost literally rendered by

the title of a specific still known in the neighbourhood of

Newcastle-on-Tyne, “Dr. Dud’s lotion, good for sore eyes.”

Besides such stamps as have already been described, the ancients used

brands, both figured and lettered, with which, when heated, they marked

their horses, sheep, and cattle, as well as criminals, captives, and

refractory or runaway slaves.

The Athenians, according to Suidas, marked their Samian captives with

the figure of an owl; while Athenians captured by the Samians were

marked with the figure of a galley, and by the Syracusans with the

figure of a horse. The husbandman at his leisure time, as we are

informed by Virgil, in the first book of the Georgics,

“Aut pecori signa, aut numeros impressit acervis;”

and from the third book we learn that the operation was performed by

branding:

“Continuoque notas et nomina gentis inurunt.”I.11

12

Such brands as those above noticed, commonly known by the name of

cauteria or stigmata, were also used for similar purposes

during the middle ages; and the practice, which has not been very long

obsolete, of burning homicides in the hand, and vagabonds and “sturdy

beggars” on the breast, face, or shoulder, affords an example of the

employment of the brand in the criminal jurisprudence of our own

country. By the 1st Edward VI. cap. 3, it was enacted, that whosoever,

man or woman, not being lame or impotent, nor so aged or diseased that

he or she could not work, should be convicted of loitering or idle

wandering by the highway-side, or in the streets, like a servant wanting

a master, or a beggar, he or she was to be marked with a hot iron on the

breast with the letter V [for Vagabond], and adjudged to the person

bringing him or her before a justice to be his slave for two years; and

if such adjudged slave should run away, he or she, upon being taken and

convicted, was to be marked on the forehead, or on the ball of the

cheek, with the letter S [for Slave], and adjudged to be the said

master’s slave for ever. By the 1st of James I. cap. 7, it was also

enacted, that such as were to be deemed “rogues, vagabonds, and sturdy

beggars” by the 39th of Elizabeth, cap. 4, being convicted at the

sessions and found to be incorrigible, were to be branded in the left

shoulder with a hot iron, of the breadth of an English shilling, marked

with a great Roman R [for Rogue]; such branding upon the shoulder to be

so thoroughly burned and set upon the skin and flesh, that the said

letter R should be seen and remain for a perpetual mark upon such rogue

during the remainder of his life.I.12

From a passage in Quintilian we learn that the Romans were acquainted

with the method of tracing letters, by means of a piece of thin

wood in which the characters were pierced or cut through, on a principle

similar to that on which the present art of stencilling is

founded. He is speaking of teaching boys to write, and the passage

referred to may be thus translated: “When the boy shall have entered

upon joining-hand, it will be useful for him to have a

copy-head of wood in which the letters are well cut, that through

its furrows, as it were, he may trace the characters with his

style. He will not thus be liable to make slips as on the wax

[alone], for he will be confined by the boundary of the letters, and

neither will he be able to deviate from his text. By thus more rapidly

and frequently following a definite outline, his hand will become

set, without his requiring any assistance from the master to

guide it.”I.13

13

A thin stencil-plate of copper, having the following letters cut

out of it,

DN CONSTAN

TIO AVG SEM

PER VICTORI

was received, together with some rare coins, from Italy by Tristan,

author of “Commentaires Historiques, Paris, 1657,” who gave a copy of it

at page 68 of the third volume of that work. The letters thus formed,

“ex nulla materia,”I.14 might be traced on paper by means of a pen, or with

a small brush, charged with body-colour, as stencillers slap-dash

rooms through their pasteboard patterns, or dipped in ink in the same

manner as many shopkeepers now, through similar thin copper-plates, mark

the prices of their wares, or their own name and address on the paper in

which such wares are wrapped.

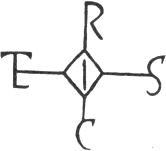

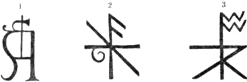

In the sixth century it appears, from Procopius, that the Emperor

Justin I. made use of a tablet of wood pierced or cut in a similar

manner, through which he traced in red ink, the imperial colour, his

signature, consisting of the first four letters of his name. It is also

stated that Theodoric, King of the Ostrogoths, the contemporary of

Justin, used after the same manner to sign the first four letters of his

name through a plate of gold;I.15 and in Peringskiold’s edition of the

Life of Theodoric, the annexed is given as the monogramI.16 of that

monarch. The authenticity of this account has, however, been questioned,

as Cochlæus, who died in 1552, cites no ancient authority for the

fact.

14

It has been asserted by Mabillon, (Diplom. lib. ii. cap. 10,) that

Charlemagne first introduced the practice of signing documents with a

monogram, either traced with a pen by means of a thin tablet of gold,

ivory, or wood, or impressed with an inked stamp, having the characters

in relief, in a manner similar to that in which letters are stamped at

the Post-office.I.17 Ducange, however, states that this mode of signing

documents is of greater antiquity, and he gives a copy of the monogram

of the Pope Adrian I. who was elected to the see of Rome in 774,

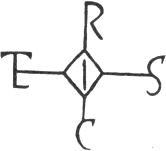

and died in 795. The annexed monogram of Charlemagne has been copied

from Peringskiold, “Annotationes in Vitam Theodorici,” p. 584; it

is also given in Ducange’s Glossary, and in the “Nouveau Traité de

Diplomatique.”

The monogram, either stencilled or stamped, consisted of a

combination of the letters of the person’s name, a fanciful

character, or the figure of a cross,I.18 accompanied with a peculiar kind

of flourish, called by French writers on diplomatics parafe or

ruche. This mode of signing appears to have been common in most

nations of Europe during the ninth, tenth, and eleventh centuries; and

it was practised by nobles and the higher orders of the clergy, as well

as by kings. It continued to be used by the kings of France to the time

of Philip III. and by the Spanish monarchs to a much later period. It

also appears to have been adopted by some of the Saxon kings of England;

and the authors of the “Nouveau Traité de Diplomatique” say that they

had seen similar marks produced by a stamp of William the Conqueror,

when Duke of Normandy. We have had a recent instance of the use of the

stampilla, as it is called by diplomatists, in affixing the royal

signature. During the illness of George IV. in 1830, a silver

stamp, containing a fac-simile of the king’s sign-manual, was executed

by Wyon, which was stamped on documents requiring the royal signature,

by commissioners, in his Majesty’s presence. A similar stamp was

used during the last illness of Henry VIII. for the purpose of affixing

the royal signature. The king’s warrant empowering commissioners to use

the stamp may be seen in Rymer’s Fœdera, vol. xv. p. 101, anno

1546. It is believed that the

15

warrant which sent the poet Surrey to the scaffold was signed with this

stamp, and not with Henry’s own hand.

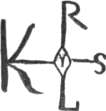

In Sempère’s “History of the Cortes of Spain,” several examples are

given of the use of fanciful monograms in that country at an early

period, and which were probably introduced by its Gothic invaders. That

such marks were stamped is almost certain; for the first, which is that

of Gundisalvo Tellez, affixed to a charter of the date of 840, is the

same as the “sign” which was affixed by his widow, Flamula, when she

granted certain property to the abbot and monks of Cardeña for the good

of her deceased husband’s soul. The second, which is of the date of 886,

was used both by the abbot Ovecus, and Peter his nephew; and the third

was used by all the four children of one Ordoño, as their “sign” to a

charter of donation executed in 1018. The fourth mark is a Runic cypher,

copied from an ancient Icelandic manuscript, and given by Peringskiold

in his “Annotations on the Life of Theodoric:” it is not given here as

being from a stencil or a stamp, but that it may be compared with the

apparently Gothic monograms used in Spain.

“In their inscriptions, and in the rubrics of their books,” says a

writer in the Edinburgh ReviewI.19 “the Spanish Goths, like the Romans

of the Lower Empire, were fond of using combined capitals—of

monogrammatising. This mode of writing is now common in Spain, on

the sign-boards and on the shop-fronts, where it has retained its place

in defiance of the canons of the council [of Leon], The Goths, however,

retained a truly Gothic custom in their writings. The Spanish

Goth sometimes subscribed his name; or he drew a monogram like

the Roman emperors, or the sign of the cross like the Saxon; but

not unfrequently he affixed strange and fanciful marks to the deed or

charter, bearing a close resemblance to the Runic or magical knots of

which so many have been engraved by Peringskiold, and other northern

antiquaries.”

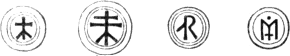

To the tenth or the eleventh century are also to be referred certain

small silver coins—“something between counters and money,” as is

observed by Pinkerton—which are impressed, on one side only, with

a kind of Runic monogram. They are formed of very thin pieces of

16

silver; and it has been supposed that the impression was produced from

wooden dies. They are known to collectors as “nummi

bracteati”—tinsel money; and Pinkerton, mistaking the Runic

character for the Christian cross, says that “most of them are

ecclesiastic.” He is perhaps nearer the truth when he adds that they

“belong to the tenth century, and are commonly found in Germany, and the

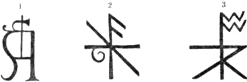

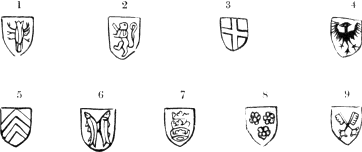

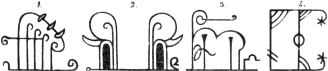

northern kingdoms of Sweden and Denmark.”I.20 The four following

copies from the original coins in the Brennerian collection are given by

Peringskiold, in his “Annotations on the Life of Theodoric,” previously

referred to. The characters on the three first he reads as the letters

EIR, OIR, and AIR,

respectively, and considers them to be intended to represent the name of

Eric the Victorious. The characters on the fourth he reads as EIM, and applies them to Emund Annosus, the

nephew of Eric the Victorious, who succeeded to the Sueo-Gothic throne

in 1051; about which time, through the influence of the monks, the

ancient Runic characters were exchanged for Roman.

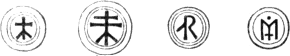

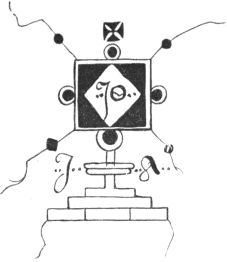

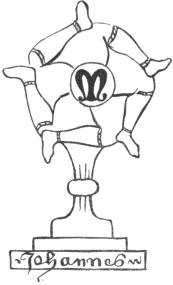

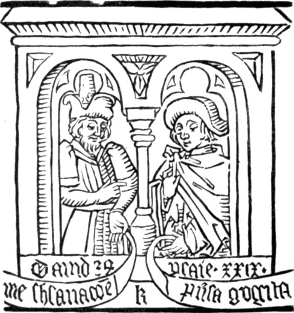

NICOLAUS FERENTERIUS, 1236

The notaries of succeeding times, who on their admission were

required to use a distinctive sign or notarial mark in witnessing an

instrument, continued occasionally to employ the stencil in affixing

their “sign;” although their use of the stamp for that purpose appears

to have been more general. In some of those marks or stamps the name of

the notary does not appear, and in others a small space is left in order

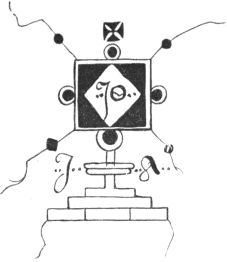

that it might afterwards be inserted with a pen. The annexed monogram

was the official mark of an Italian notary, Nicolaus Ferenterius, who

lived in 1236.I.21

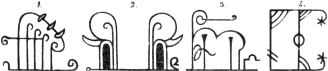

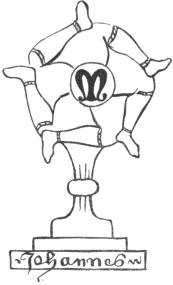

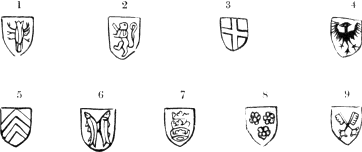

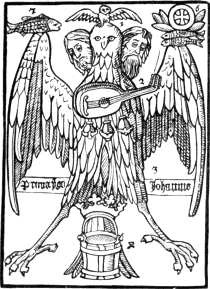

The three following cuts represent impressions of German notarial

stamps. The first is that of Jacobus Arnaldus, 1345; the second that of

Johannes Meynersen, 1435; and the third that of Johannes Calvis, 1521.I.22

17

JACOBUS ARNALDUS, 1345.

JOHANNES MEYNERSEN, 1435.

JOHANNES CALVIS, 1521.

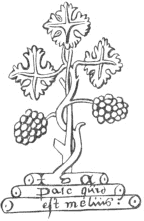

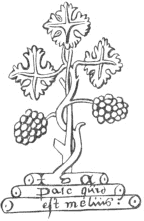

Many of the merchants’-marks of our own country, which so frequently

appear on stained glass windows, monumental brasses, and tombstones in

the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries, bear a considerable

likeness to the ancient Runic monograms, from which it is not unlikely

that they were originally derived. The English trader was accustomed to

place his mark as his “sign” in his shop-front in the same manner as the

Spaniard did his monogram: if he was a wool-stapler, he stamped it on

his packs; or if a fish-curer, it was branded on the end of his casks.

If he built himself a new house, his mark

18

was frequently placed between his initials over the principal door-way,

or over the fireplace of the hall; if he made a gift to a church or a

chapel, his mark was emblazoned on the windows beside the knight’s or

the nobleman’s shield of arms; and when he died, his mark was cut upon

his tomb. Of the following merchants’-marks, the first is that of Adam

de Walsokne, who died in 1349; the second that of Edmund Pepyr, who died

in 1483; those two marks are from their tombs in St. Margaret’s, Lynn;

and the third is from a window in the same church.I.23

In Pierce Ploughman’s Creed, written after the death of Wickliffe,

which happened in 1384, and consequently more modern than many of

Chaucer’s poems, merchants’-marks are thus mentioned in the description

of a window of a Dominican convent:

“Wide windows y-wrought, y-written full thick,

Shining with shapen shields, to shewen about,

With marks of merchants, y-meddled between,

Mo than twenty and two, twice y-numbered.I.24”

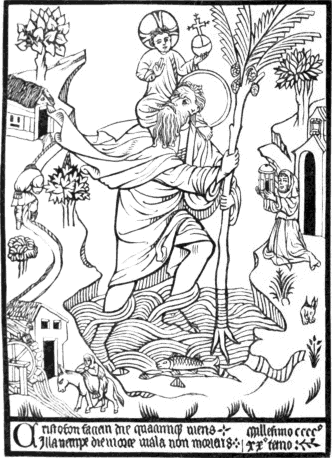

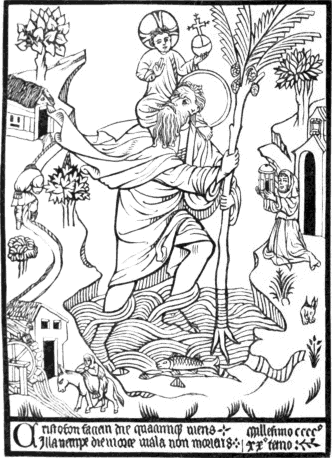

Having thus endeavoured to prove by a continuous chain of evidence

that the principle of producing impressions from raised lines was known,

and practised, at a very early period; and that it was applied for the

purpose of impressing letters and other characters on paper, though

perhaps confined to signatures only, long previous to 1423,—which

is the earliest date that has been discovered on a wood-cut, in the

modern sense of the word, impressed on paper, and accompanied with

explanatory words cut on the same block;I.25 and having shown that the

principle of stencilling—the manner in which the above-named cut

is

19

colouredI.26—was also known in the middle ages; it appears

requisite, next to briefly notice the contemporary existence of the

cognate arts of die-sinking, seal-cutting, and engraving on brass, and

afterwards to examine the grounds of certain speculations on the

introduction and early practice of wood-engraving and block-printing in

Europe.

Concerning the first invention of stamping letters and figures upon

coins, and the name of the inventor, it is fruitless to inquire, as the

origin of the art is lost in the remoteness of antiquity. “Leaving these

uncertainties,” says Pinkerton, in his Essay on Medals, “we know from

respectable authorities that the first money coined in Greece was that

struck in the island of Ægina, by Phidon king of Argos. His reign is

fixed by the Arundelian marbles to an era correspondent to the 885th

year before Christ; but whether he derived this art from Lydia or any

other source we are not told.” About three hundred years before the

birth of Christ, the art of coining, so far as relates to the beauty of

the heads impressed, appears to have attained its perfection in

Greece;—we may indeed say its perfection generally, for the

specimens which were then produced in that country remain unsurpassed by

modern art. Under the Roman emperors the art never seems to have

attained so high a degree of perfection as it did in Greece; though

several of the coins of Hadrian, probably executed by Greek artists,

display great beauty of design and execution. The art of coining, with

the rest of the ornamental arts, declined with the empire; and, on its

final subversion in Italy, the coins of its rulers were scarcely

superior to those which were subsequently minted in England, Germany,

and France, during the darkest period of the middle ages.

The art of coining money, however rude in design and imperfect in its

mode of stamping the impression, which was by repeated blows with a

hammer, was practised from the twelfth to the sixteenth century in a

greater number of places than at present; for many of the more powerful

bishops and nobles assumed or extorted the right of coining money as

well as the king; and in our own country the archbishops of Canterbury

and York, and the bishop of Durham, exercised the right of coinage till

the Reformation; and local mints for coining the king’s money were

occasionally fixed at Norwich, Chester, York, St. Edmundsbury,

Newcastle-on-Tyne, and other places. Independent of those establishments

for the coining of money, almost every abbey struck its own

jettons or

20

counters; which were thin pieces of copper, commonly impressed with a

pious legend, and used in casting up accounts, but which the

general introduction of the numerals now in use, and an improved system

of arithmetic, have rendered unnecessary. As such mints were at least as

numerous in France and Germany as in our own country, Scheffer, the

partner of Faust, when he conceived the idea of casting letters from

matrices formed by punches, would have little difficulty in finding a

workman to assist him in carrying his plans into execution. “The art of

impressing legends on coins,” says Astle in his Account of the Origin

and Progress of writing, “is nothing more than the art of printing on

medals.” That the art of casting letters in relief, though not

separately, and most likely from a mould of sand, was known to the

Romans, is evident from the names of the emperors Domitian and Hadrian

on some pigs of lead in the British Museum; and that it was practised

during the middle and succeeding ages, we have ample testimony from the

inscriptions on our ancient bells.I.27

In the century immediately preceding 1423, the date of the wood-cut

of St. Christopher, the use of seals, for the purpose of authenticating

documents by their impression on wax, was general throughout Europe;

kings, nobles, bishops, abbots, and all who “came of gentle

blood,” with corporations, lay and clerical, all had seals. They were

mostly of brass, for the art of engraving on precious stones does not

appear to have been at that time revived, with the letters and device

cut or cast in hollow—en creux—on the face of the

seal, in order that the impression might appear raised. The workmanship

of many of those seals, and more especially of some of the conventional

ones, where figures of saints and a view of the abbey are introduced,

displays no mean degree of skill. Looking on such specimens of the

graver’s art, and bearing in mind the character of many of the drawings

which are to be seen in the missals and other manuscripts of the

fourteenth century and of the early part of the fifteenth, we need no

longer be surprised that the cuts of the earliest block-books should be

so well executed.

The art of engraving on copper and other metals, though not with the

intention of taking impressions on paper, is of great antiquity. In the

late Mr. Salt’s collection of Egyptian antiquities there was a small

axe, probably a model, the head of which was formed of sheet-copper, and

was tied, or rather bandaged, to the helve with slips of cloth. There

were certain characters engraved upon the head in such a manner that if

it were inked and submitted to the action of the rolling-press,

impressions would be obtained as from a modern copper-plate. The axe,

with other

21

models of a carpenter’s tools, also of copper, was found in a tomb in

Egypt, where it must have been deposited at a very early period. That

the ancient Greeks and Romans were accustomed to engrave on copper and

other metals in a similar manner, is evident from engraved pateræ and

other ornamental works executed by people of those nations. Though no

ancient writer makes mention of the art of engraving being employed for

the purpose of producing impressions on paper, yet it has been

conjectured by De Pauw, from a passage in Pliny,I.28 that such an art was

invented by Varro for the purpose of multiplying the portraits of

eminent men. “No Greek,” says De Pauw, speaking of engraving, “has the

least right to claim this invention, which belongs exclusively to Varro,

as is expressed by Pliny in no equivocal terms, when he calls this

method inventum Varronis. Engraved plates were employed which

gave the profile and the principal traits of the figures, to which the

appropriate colours and the shadows were afterwards added with the

pencil. A woman, originally of Cyzica, but then settled in Italy,

excelled all others in the talent of illumining such kind of prints,

which were inserted by Varro in a large work of his entitled

‘Imagines’ or ‘Hebdomades,’ which was enriched with seven

hundred portraits of distinguished men, copied from their statues and

busts. The necessity of exactly repeating each portrait or figure in

every copy of the work suggested the idea of multiplying them without

much cost, and thus gave birth to an art till then unknown.”I.29 The

grounds, however, of this conjecture are extremely slight, and will not

without additional support sustain the superstructure which De

Pauw—an “ingenious” guesser, but a superficial inquirer—has

so plausibly raised. A prop for this theory has been sought for by

men of greater research than the original propounder, but hitherto

without success.

About the year 1300 we have evidence of monumental brasses, with

large figures engraved on them, being fixed on tombs in this country;

and it is not unlikely that they were known both here and on the

22

Continent at an earlier period. The best specimens known in this country

are such as were in all probability executed previous to 1400. In the

succeeding century the figures and ornamental work generally appear to

be designed in a worse taste and more carelessly executed; and in the

age of Queen Elizabeth the art, such as it was, appears to have reached

the lowest point of degradation, the monumental brasses of that reign

being generally the worst which are to be met with.

The figures on several of the more ancient brasses are well drawn,

and the folds of the drapery in the dresses of the females are, as a

painter would say, “well cast;” and the faces occasionally display a

considerable degree of correct and elevated expression. Many of the

figures are of the size of life, marked with a hold outline well

ploughed into the brass, and having the features, armour, and drapery

indicated by single lines of greater or less strength as might be

required. Attempts at shading are also occasionally to be met with; the

effect being produced by means of lines obliquely crossing each other in

the manner of cross-hatchings. Whether impressions were ever taken or

not from such early brasses by the artists who executed them, it is

perhaps now impossible to ascertain; but that they might do so is beyond

a doubt, for it is now a common practice, and two immense volumes of

impressions taken from monumental brasses, for the late Craven Ord,

Esq., are preserved in the print-room of the British Museum.

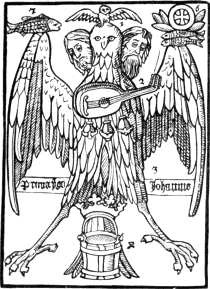

One of the finest monumental brasses known in this country is that of

Robert Braunche and his two wives, in St. Margaret’s Church, Lynn, where

it appears to have been placed about the year 1364. Braunche, and his

two wives, one on each side of him, are represented standing, of the

size of life. Above the figures are representations of five small niches

surmounted by canopies in the florid Gothic style. In the centre niche

is the figure of the Deity holding apparently the infant Christ in his

arms. In each of the niches adjoining the centre one is an angel

swinging a censer; and in the exterior niches are angels playing on

musical instruments. At the sides are figures of saints, and at the foot

there is a representation of a feast, where persons are seen seated at

table, others playing on musical instruments, while a figure kneeling

presents a peacock. The length of this brass is eight feet eleven

inches, and its breadth five feet two inches. It is supposed to have

been executed in Flanders, with which country at that period the town of

Lynn was closely connected in the way of trade.I.30

It has frequently been asserted that the art of wood engraving in

Europe was derived from the Chinese; by whom, it is also said, that the

23

art was practised in the reign of the renowned emperor Wu-Wang, who

flourished 1120 years before the birth of Christ. As both these

statements seem to rest on equal authorities, I attach to each an

equal degree of credibility; that is, by believing neither. As Mr.

Ottley has expressed an opinion in favour of the Chinese origin of the

art,—though without adopting the tale of its being practised in

the reign of Wu-Wang, which he shows has been taken by the wrong

end,—I shall here take the liberty of examining the tenability of

his arguments.

At page 8, in the first chapter of his work, Mr. Ottley cautiously

says that the “art of printing from engraved blocks of wood appears to

be of very high antiquity amongst the Chinese;” and at page 9,

after citing Du Halde, as informing us that the art of printing was not

discovered until about fifty years before the Christian era, he rather

inconsistently observes: “So says Father Du Halde, whose authority I

give without any comment, as the defence of Chinese chronology makes no

part of the present undertaking.” Unless Mr. Ottley is satisfied of the

correctness of the chronology, he can by no means cite Du Halde’s

account as evidence of the very high antiquity of printing in China;

which in every other part of his book he speaks of as a well-established

fact, and yet refers to no other authority than Du Halde, who relies on

the correctness of that Chinese chronology with the defence of which Mr.

Ottley will have nothing to do.

It is also worthy of remark, that in the same chapter he corrects two

writers, Papillon and Jansen, for erroneously applying a passage in Du

Halde as proving that the art of printing was known in the reign of

Wu-Wang,—he who flourished Ante Christum 1120; whereas the said

passage was not alleged “by Du Halde to prove the antiquity of printing

amongst the Chinese, but solely in reference to their ink.” The passage,

as translated by Mr. Ottley, is as follows: “As the stone Me”

(a word signifying ink in the Chinese language), “which is used to

blacken the engraved characters, can never become white; so a

heart blackened by vices will always retain its blackness.” The engraved

characters were not inked, it appears, for the purpose of taking

impressions, as Messrs. Papillon and Jansen have erroneously inferred.

“It is possible,” according to Mr. Ottley, “that the ink might be used

by the Chinese at a very early period to blacken, and thereby render

more easily legible, the characters of engraved inscriptions.”I.31 The

possibility of this may be granted certainly; but at the same

time we must admit that it is equally possible that the engraved

characters were blackened with ink for the purpose of being printed, if

they were of wood; or that, if

24

cut in copper or other metal, they were filled with a black composition

which would harden or set in the lines,—as an ingenious

inquirer might infer from ink being represented by the

stone ME; and thus it is

possible that something very like “niello,” or the filling of

letters on brass doorplates with black wax, was known to the Chinese in

the reign of Wu-Wang, who flourished in the year before our Lord, 1120.

The one conjecture is as good as the other, and both good for nothing,

until we have better assurance than is afforded by Du Halde, that

engraved characters blackened with ink—for whatever

purpose—were known by the Chinese in the reign of Wu-Wang.I.32

Although so little is positively known of the ancient history of “the

great out-lying empire of China,” as it is called by Sir William Jones,

yet it has been most confidently referred to as affording authentic

evidence of the high degree of the civilization and knowledge of the

Chinese at a period when Europe was dark with the gloom of barbarism and

ignorance. Their early history has been generally found, when

opportunity has been afforded of impartially examining it, to be a mere

tissue of absurd legends; compared to which, the history of the

settlement of King Brute in Britain is authentic. With astronomy as a

science they are scarcely acquainted; and their specimens of the fine

arts display little more than representations of objects executed not

unfrequently with minute accuracy, but without a knowledge of the most

simple elements of correct design, and without the slightest pretensions

to art, according to our standard.

One of the two Mahometan travellers who visited China in the ninth

century, expressly states that the Chinese were unacquainted with the

sciences; and as neither of them takes any notice of printing, the

mariner’s compass, or gunpowder, it seems but reasonable to conclude

that the Chinese were unacquainted with those inventions at that

period.I.33

Mr. Ottley, at pages 51 and 52 of his work, gives a brief account of

25

the early commerce of Venice with the East, for the purpose of showing

in what manner a knowledge of the art of printing in China might be

obtained by the Venetians. He says: “They succeeded, likewise, in

establishing a direct traffic with Persia, Tartary, China, and Japan;

sending, for that purpose, several of their most respectable citizens,

and largely providing them with every requisite.” He cites an Italian

author for this account, but he observes a prudent silence as to the

period when the Venetians first established a direct traffic with

China and Japan; though there is little doubt that Bettinelli, the

authority referred to, alludes to the expedition of the two brothers

Niccolo and Maffeo Polo, and of Marco Polo, the son of Niccolo, who in

1271 or 1272 left Venice on an expedition to the court of the Tartar

emperor Kublai-Khan, which had been previously visited by the two

brothers at some period between 1254 and 1269.I.34 After having visited

Tartary and China, the two brothers and Marco returned to Venice in

1295. Mr. Ottley, however, does not refer to the travels of the Polos

for the purpose of showing that Marco, who at a subsequent period wrote

an account of his travels, might introduce a knowledge of the Chinese

art of printing into Europe: he cites them that his readers may suppose

that a direct intercourse between Venice and China had been established

long before; and that the art of engraving wood-blocks, and taking

impressions from them, had been thus derived from the latter country,

and had been practised in Venice long before the return of the

travellers in 1295.

It is necessary here to observe that the invention of the mariner’s

compass, and of gunpowder and cannon, have been ascribed to the Chinese

as well as the invention of wood engraving and block-printing; and it

has been conjectured that very probably Marco Polo communicated

to his countrymen, and through them to the rest of Europe,

a knowledge of those arts. Marco Polo, however, does not in the

account which he wrote of his travels once allude to gunpowder, cannon,

or to the art of printing as being known in China;I.35 nor does he once

mention the compass as being used on board of the Chinese vessel in

which he sailed from the coast of China to the Persian Gulf. “Nothing is

more common,”

26

says a writer in the Quarterly Review, “than to find it repeated from

book to book, that gunpowder and the mariner’s compass were first

brought from China by Marco Polo, though there can be very little doubt

that both were known in Europe some time before his return.”—“That

Marco Polo,” says the same writer, “would have mentioned the mariner’s

compass, if it had been in use in China, we think highly probable; and

his silence respecting gunpowder may be considered as at least a

negative proof that this also was unknown to the Chinese in the time of

Kublai-Khan.”I.36 In a manner widely different from this does Mr.

Ottley reason, respecting the cause of Marco Polo not having mentioned

printing as an art practised by the Chinese. He accounts for the

traveller’s silence as follows: “Marco Polo, it may be said, did not

notice this art [of engraving on wood and block-printing] in the account

which he left us of the marvels he had witnessed in China. The answer to

this objection is obvious: it was no marvel; it had no novelty to

recommend it; it was practised, as we have seen, at Ravenna, in 1285,

and had perhaps been practised a century earlier in Venice. His mention

of it, therefore, was not called for, and he preferred instructing his

countrymen in matters with which they were not hitherto acquainted.”

This “obvious” answer, rather unfortunately, will equally apply to the

question, “Why did not Marco Polo mention cannon as being used by the

Chinese, who, as we are informed, had discovered such formidable engines

of war long before the period of his visit?”

That the art of engraving wood-blocks and of taking impressions from

them was introduced into Europe from China, I can see no sufficient

reason to believe. Looking at the frequent practice in Europe, from the

twelfth to the fifteenth century, of impressing inked stamps on paper,

I can perceive nothing in the earliest specimens of wood engraving

but the same principles applied on a larger scale. When I am once

satisfied that a man had built a small boat, I feel no surprise on

learning that his grandson had built a larger; and made in it a longer

voyage than his ancestor ever ventured on, who merely used his slight

skiff to ferry himself across a river.

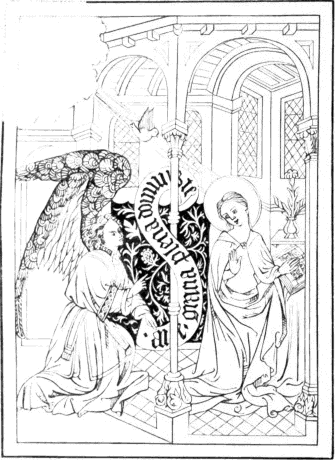

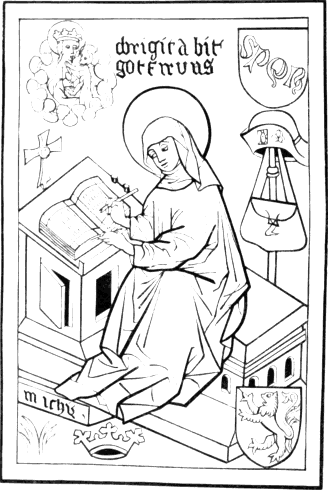

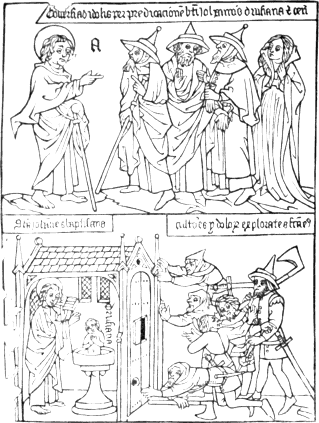

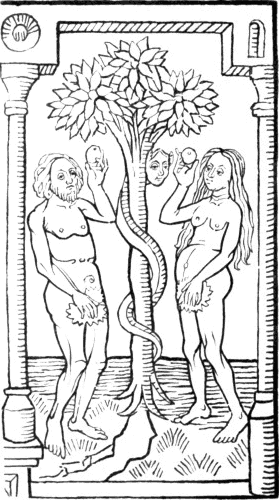

In the first volume of Papillon’s “Traité de la Gravure en Bois,”

there is an account of certain old wood engravings which he professes to

have seen, and which, according to their engraved explanatory title,

were executed by two notable young people, Alexander Alberic Cunio,

knight, and Isabella Cunio, his twin sister, and finished by them

when they were only sixteen years old, at the time when Honorius IV. was

pope; that is, at some period between the years 1285 and 1287. This

27

story has been adopted by Mr. Ottley, and by Zani, an Italian, who give

it the benefit of their support. Mr. Singer, in his “Researches into the

History of Playing Cards,” grants the truth-like appearance of

Papillon’s tale; and the writer of the article “Wood-engraving” in the

Encyclopedia Metropolitana considers it as authentic. It is, however,

treated with contempt by Heineken, Huber, and Bartsch, whose knowledge

of the origin and progress of engraving is at least equal to that of the

four writers previously named.

The manner in which Papillon recovered his memoranda of the works of

the Cunio is remarkable. In consequence of those curious notes being

mislaid for upwards of thirty-five years, the sole record of the

productions of those “ingenious and amiable twins” was very nearly lost

to the world. The three sheets of letter-paper on which he had

written an account of certain old volumes of wood engravings,—that

containing the cuts executed by the Cunio being one of the

number,—he had lost for upwards of thirty-five years. For long he

had only a confused idea of those sheets, though he had often searched

for them in vain, when he was writing his first essay on wood engraving,

which was printed about 1737, but never published. At length he

accidentally found them, on All-Saints’ Day, 1758, rolled up in a bundle

of specimens of paper-hangings which had been executed by his father.

The finding of those three sheets afforded him the greater pleasure, as

from them he discovered, by means of a pope’s name, an epoch of

engraving figures and letters on wood for the purpose of being printed,

which was certainly much earlier than any at that period known in

Europe, and at the same time a history relative to this subject equally

curious and interesting. He says that he had so completely forgotten all

this,—though he had so often recollected to search for his

memoranda,—that he did not deign to take the least notice of it in

his previously printed history of the art. The following is a faithful

abstract of Papillon’s account of his discovery of those early specimens

of wood engraving. The title-page, as given by him in French from

Monsieur De Greder’s vivâ voce translation of the

original,—which was “en mauvais Latin ou ancien Italien Gothique,

avec beaucoup d’abréviations,”—is translated without abridgment,

as are also his own descriptions of the cuts.

“When young, being engaged with my father in going almost every day

to hang rooms with our papers, I was, some time in 1719 or 1720, at

the village of Bagneux, near Mont Rouge, at a Monsieur De Greder’s,

a Swiss captain, who had a pretty house there. After I had papered

a small room for him, he ordered me to cover the shelves of his library

with paper in imitation of mosaic. One day after dinner he surprised me

reading a book, which occasioned him to show me some very old ones which

he had borrowed of one of his friends, a Swiss officer,I.37 that

28

he might examine them at his leisure. We talked about the figures which

they contained, and of the antiquity of wood engraving; and what follows

is a description of those ancient books as I wrote it before him, and as

he was so kind as to explain and dictate to me.

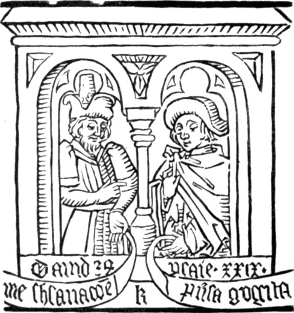

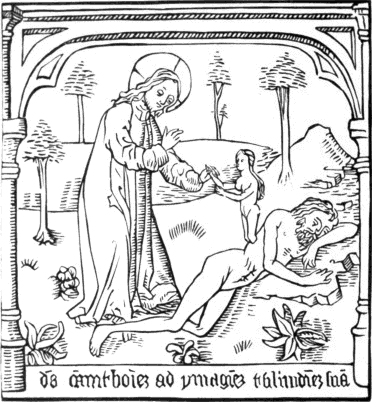

“In a cartouchI.38 or frontispiece,—of fanciful and Gothic

ornaments, though pleasing enough,—nine inches wide, and six

inches high, having at the top the arms, doubtless, of Cunio, the

following words are coarsely engraved on the same block, in bad Latin,

or ancient Gothic Italian with many abbreviations.

“‘The chivalrous deeds, in figures,

of the great and magnanimous Macedonian king, the courageous and valiant

Alexander, dedicated, presented, and humbly offered to the most holy

father, Pope Honorius IV. the glory and stay of the Church, and to our

illustrious and generous father and mother, by us Alexander Alberic

Cunio, knight, and Isabella Cunio, twin brother and sister; first

reduced, imagined, and attempted to be executed in relief with a little

knife, on blocks of wood, joined and smoothed by this learned and

beloved sister, continued and finished together at Ravenna, after eight

pictures of our designing, painted six times the size here represented;

cut, explained in verse, and thus marked on paper to multiply the

number, and to enable us to present them as a token of friendship and

affection to our relations and friends. This was done and finished, the

age of each being only sixteen years complete.’”

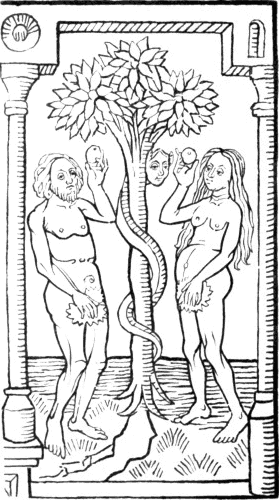

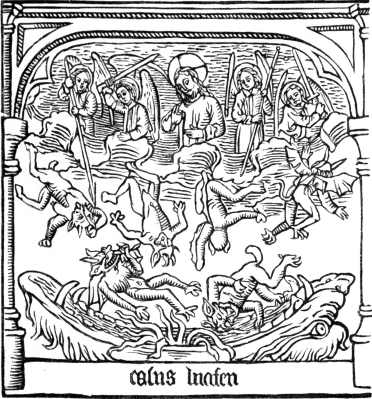

After having given the translation of the title-page, Papillon thus

continues the narrative in his own person: “This cartouch [or

ornamented title-page] is surrounded by a coarse line, the tenth of an

inch broad, forming a square. A few slight lines, which are

irregularly executed and without precision, form the shading of the

ornaments. The impression, in the same manner as the rest of the cuts,

has been taken in Indian blue, rather pale, and in distemper, apparently

by the hand being passed frequently over the paper laid upon the block,

as card-makers are accustomed to impress their addresses and the

envelopes of their cards. The hollow parts of the block, not being

sufficiently cut away in several places, and having received the ink,

have smeared the paper, which is rather brown; a circumstance which

has caused the following words to be written in the margin underneath,

that the fault might be remedied.

29

They are in Gothic Italian, which M. de Greder had considerable

difficulty in making out, and certainly written by the hand either of

the Chevalier Cunio or his sister, on this first proof—evidently

from a block—such as are here translated.”

“‘It is necessary to cut away the ground of the blocks more, that

the paper may not touch it in taking impressions.’”

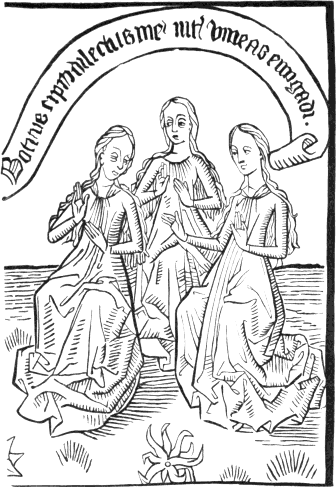

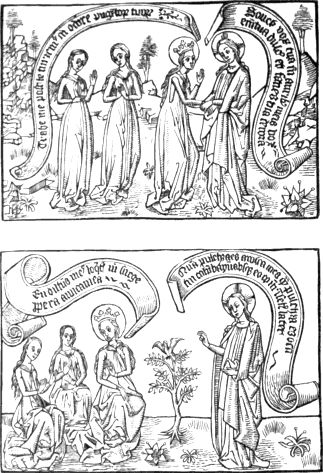

“Following this frontispiece, and of the same size, are the subjects

of the eight pictures, engraved on wood, surrounded by a similar line

forming a square, and also with the shadows formed of slight lines. At

the foot of each of those engravings, between the border-line and

another, about a finger’s breadth distant, are four Latin verses

engraved on the block, poetically explaining the subject, the title of

which is placed at the head. In all, the impression is similar to that

of the frontispiece, and rather grey or cloudy, as if the paper had not

been moistened. The figures, tolerably designed, though in a semi-gothic

taste, are well enough characterized and draped; and we may perceive

from them that the arts of design were then beginning gradually to

resume their vigour in Italy. At the feet of the principal figures their

names are engraved, such as Alexander, Philip, Darius, Campaspe,

and others.”

“Subject 1.—Alexander mounted

on Bucephalus, which he has tamed. On a stone are these words:

Isabel. Cunio pinx. & scalp.”

“Subject 2.—Passage of the

Granicus. Near the trunk of a tree these words are engraved: Alex.

Alb. Cunio Equ. pinx. Isabel Cunio scalp.”

“Subject 3.—Alexander cutting

the Gordian knot. On the pedestal of a column are these words:

Alexan. Albe. Cunio Equ. pinx. & scalp. This block is not so

well engraved as the two preceding.”

“Subject 4.—Alexander in the

tent of Darius. This subject is one of the best composed and engraved of

the whole set. Upon the end of a piece of cloth are these words:

Isabel. Cunio pinxit & scalp.”

“Subject 5.—Alexander

generously presents his mistress Campaspe to Apelles who was painting

her. The figure of this beauty is very agreeable. The painter seems

transported with joy at his good fortune. On the floor, on a kind of

antique tablet, are these words: Alex. Alb. Cunio Eques, pinx. &

scalp.”

“Subject 6.—The famous battle

of Arbela. Upon a small hillock are these words: Alex. Alb. Equ.

& Isabel. pictor. and scalp. For composition, design, and

engraving, this subject is also one of the best.”

“Subject 7.—Porus, vanquished,

is brought before Alexander. This subject is so much the more beautiful

and remarkable, as it is composed nearly in the same manner as that of

the famous Le Brun; it would seem that he had copied this print. Both

Alexander and Porus have a grand

30

and magnanimous air. On a stone near a bush are engraved these words:

Isabel. Cunio pinx. & scalp.”

“Subject 8 and last.—The glory

and grand triumph of Alexander on entering Babylon. This piece, which is

well enough composed, has been executed, as well as the sixth, by the

brother and sister conjointly, as is testified by these characters

engraved at the bottom of a wall: Alex. Alb. Equ. et Isabel. Cunio,

pictor. & scalp. At the top of this impression, a piece

about three inches long and one inch broad has been torn off.”

However singular the above account of the works of those “amiable

twins” may seem, no less surprising is the history of their birth,

parentage, and education; which, taken in conjunction with the early

development of their talents as displayed in such an art, in the choice

of such a subject, and at such a period, is scarcely to be surpassed in

interest by any narrative which gives piquancy to the pages of the

Wonderful Magazine.

Upon the blank leaf adjoining the last engraving were the following

words, badly written in old Swiss characters, and scarcely legible in

consequence of their having been written with pale ink. “Of course

Papillon could not read Swiss,” says Mr. Ottley, “M. de Greder,

therefore, translated them for him into French.”—“This precious

volume was given to my grandfather Jan. Jacq. Turine, a native of

Berne, by the illustrious Count Cunio, chief magistrate of Imola, who

honoured him with his generous friendship. Above all my books I prize

this the highest on account of the quarter from whence it came into our

family, and on account of the knowledge, the valour, the beauty, and the

noble and generous desire which those amiable twins Cunio had to gratify

their relations and friends. Here ensues their singular and curious

history as I have heard it many a time from my venerable father, and

which I have caused to be more correctly written than I could do it

myself.”

Though Papillon’s long-lost manuscript, containing the whole account

of the works of the Cunio and notices of other old books of engravings,

consisted of only three sheets of letter-paper, yet the history alone of

the learned, beautiful, and amiable twins, which Turine the grandson

caused to be written out as he had heard it from his father, occupies in

Papillon’s book four long octavo pages of thirty-eight lines each. To

assume that his long-lost manuscript consisted of brief notes which he

afterwards wrote out at length from memory, would at once destroy any

validity that his account might be supposed to possess; for he states

that he had lost those papers for upwards of thirty five years, and had

entirely forgotten their contents.

Without troubling myself to transcribe the whole of this choice

morsel of French Romance concerning the history of the “amiable

31

twins” Cunio,—the surprising beauty, talents, and accomplishments

of the maiden,—the early death of herself and her lover,—the

heroism of the youthful knight, Alexander Alberic Cunio, displayed when

only fourteen years old,—I shall give a brief abstract of some of

the passages which seem most important to the present inquiry.I.39

From this narrative,—which Papillon informs us was written in a

much better hand, though also in Swiss characters, and with much blacker

ink than Turine the grandson’s own memorandum,—we obtain the

following particulars: The Count de Cunio, father of the twins, was

married to their mother, a noble maiden of Verona and a relation of

Pope Honorius IV. without the knowledge of their parents, who, on

discovering what had happened, caused the marriage to be annulled, and

the priest by whom it was celebrated to be banished. The divorced wife,

dreading the anger of her own father, sought an asylum with one of her

aunts, under whose roof she was brought to bed of twins. Though the

elder Cunio had compelled his son to espouse another wife, he yet

allowed him to educate the twins, who were most affectionately received

and cherished by their father’s new wife. The children made astonishing

progress in the sciences, more especially the girl Isabella, who at

thirteen years of age was regarded as a prodigy; for she understood, and

wrote with correctness, the Latin language; she composed excellent

verses, understood geometry, was acquainted with music, could play on

several instruments, and had begun to design and to paint with

correctness, taste, and delicacy. Her brother Alberic, of a beauty as

ravishing as his sister’s, and one of the most charming youths in Italy,

at the age of fourteen could manage the great horse, and understood the

practice of arms and all other exercises befitting a young man of

quality. He also understood Latin, and could paint well.

The troubles in Italy having caused the Count Cunio to take up arms,

his son, young Alexander Alberic, accompanied him to the field to make

his first campaign. Though not more than fourteen years old, he was

entrusted with the command of a squadron of twenty-five horse, with

which, as his first essay in war, he attacked and put to flight near two

hundred of the enemy. His courage having carried him too far, he was

surrounded by the fugitives, from whom, however, he fought himself clear

without any further injury than a wound in his left arm. His father, who

had hastened to his succour, found him returning with the enemy’s

banner, which he had wrapped about his wound. Delighted at the valour

displayed by his son, the Count Cunio knighted him on the spot. The

young man then asked permission to visit his mother, which

32

was readily granted by the count, who was pleased to have this

opportunity of testifying the love and esteem he still retained towards

that noble and afflicted lady, who continued to reside with her aunt; of

which he certainly would have given her more convincing proofs, now that

his father was dead, by re-establishing their marriage and publicly

espousing her, if he had not been in duty bound to cherish the wife whom

he had been compelled to marry, and who had now borne him a large

family.

After Alexander Alberic had visited his mother, he returned home, and

shortly after began, together with his sister Isabella, to design and

work upon the pictures of the achievements of Alexander. He then made a

second campaign with his father, after which he continued to employ

himself on the pictures in conjunction with Isabella, who attempted in

reduce them and engrave them on wood. After the engravings were

finished, and copies had been printed and given to Pope Honorius, and

their relations and friends, Alexander Alberic proceeded again to join

the army, accompanied by Pandulphio, a young nobleman, who was in

love with the charming Isabella. This was his last campaign, for he was

killed in the presence of his friend, who was dangerously wounded in

defending him. He was slain when not more than nineteen; and his sister

was so affected by his death that she resolved never to marry, and died

when she was scarcely twenty. The death of this lovely and learned young

lady was followed by that of her lover, who had fondly hoped that she

would make him happy. The mother of those amiable twins was not long in

following them to the grave, being unable to survive the loss of her

children. The Countess de Cunio took seriously ill at the loss of

Isabella, but fortunately recovered; and it was only the count’s

grandeur of soul that saved him from falling sick also.

Some years after this, Count Cunio gave the copy of the achievements

of Alexander, in its present binding, to the grandfather of the person

who caused this account to be written. The binding, according to

Papillon’s description of it, was, for the period, little less

remarkable than the contents. “This ancient and Gothic binding,” as

Papillon’s note is translated by Mr. Ottley. “is made of thin tablets of

wood, covered with leather, and ornamented with flowered

compartments, which appear simply stamped and marked with an iron a

little warmed, without any gilding.” It is remarkable that this

singular volume should afford not only specimens of wood engraving,

earlier by upwards of a hundred and thirty years than any which are

hitherto known, but that the binding, of the same period as the

engravings, should also be such as is rarely, if ever, to be met with

till upwards of one hundred and fifty years after the wonderful twins

were dead.

33

As this volume is no longer to be found, as no mention is made of

such a work by any old writer, and as another copy has not been

discovered in any of the libraries of Italy, nor the least trace of one

ever having been there, the evidence of its ever having existed rests

solely on the account given of it by Papillon. Before saying a word

respecting the credit to be attached to this witness, or the props with

which Zani and Ottley endeavour to support his testimony, I shall

attempt to show that the account affords internal evidence of its own

falsehood.

Before noticing the description of the subjects, I shall state a few

objections to the account of the twins as written out by order of the

youngest Turine, the grandson of Jan. Jacq. Turine, who received the