Faust and scheffer’s psalter of 1457—printing at bamberg in

1461—books containing wood-cuts printed there by albert

pfister—opposition of the wood engravers of augsburg to the

earliest printers established in that city—travelling

printers—wood-cuts in “meditationes johannis de turre-cremata,”

rome, 1467; and in “valturius de re militari,” verona,

1472—wood-cuts frequent in books printed at augsburg between 1474

and 1480—wood-cuts in books printed by caxton—maps engraved

on wood, 1482—progress of map

engraving—cross-hatching—flowered borders—hortus

sanitatis—nuremberg chronicle—wood engraving in

italy—poliphili hypnerotomachia—decline of

block-printing—old wood-cuts in derschau’s collection.

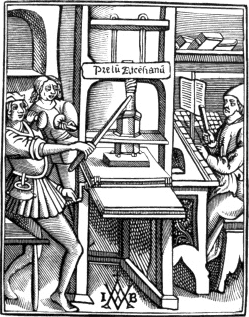

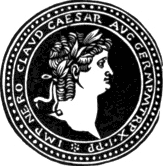

onsidering

Gutemberg as the inventor of printing with moveable types; that his

first attempts were made at Strasburg about 1436; and that with Faust’s

money and Scheffer’s ingenuity the art was perfected at Mentz about

1452, I shall now proceed to trace the progress of wood engraving

in its connexion with the press.

In the first book which appeared with a date and the printers’

names—the Psalter printed by Faust and Scheffer, at Mentz, in

1457—the large initial letters, engraved on wood and printed in

red and blue ink, are the must beautiful specimens of this kind of

ornament which the united efforts of the wood-engraver and the pressman

have produced. They have been imitated in modern times, but not

excelled. As they are the first letters, in point of time, printed with

two colours, so are they likely to continue the first in point of

excellence.

Only seven copies of the Psalter of 1457 are known, and they are all

printed on vellum. Although they have all the same colophon, containing

the printers’ names and the date, yet no two copies exactly correspond.

A similar want of agreement is said to have been observed in

different copies of the Mazarine Bible, but which are, notwithstanding,

of one and the same edition. As such works would in the infancy of the

art be a long time in printing—more especially the Psalter, as,

165

in consequence of the large capitals being printed in two colours, each

side of many of the sheets would have to be printed thrice—it can

be a matter of no surprise that alterations and amendments should be

made in the text while the work was going through the press. In the

Mazarine Bible, the entire Book of Psalms, which contains a considerable

number of red letters, would have to pass four times through the press,

including what printers call the “reiteration.”IV.1

The largest of the ornamented capitals in the Psalter of 1457 is the

letter B, which stands at the commencement of the first psalm, “Beatus

vir.” The letters which are next in size are an A, a C, a D, an E,

and a P; and there are also others of a smaller size, similarly

ornamented, and printed in two colours in the same manner as the larger

ones. Although only two colours are used to each letter, yet when the

same letter is repeated a variety is introduced by alternating the

colours: for instance, the shape of the letter is in one page printed

red, with the ornamental portions blue; and in another the shape of the

letter is blue, and the ornamental portions red. It has been erroneously

stated by Papillon that the large letters at the beginning of each psalm

are printed in three colours, red, blue, and purple; and Lambinet has

copied the mistake. A second edition of this Psalter appeared in

1459; a third in 1490; and a fourth in 1502, all in folio, like the

first, and with the same ornamented capitals. Heineken observes that in

the edition of 1490 the large letters are printed in red and green

instead of red and blue.

In consequence of those large letters being printed in two colours,

two blocks would necessarily be required for each; one for that portion

of the letter which is red, and another for that which is blue. In the

body, or shape, of the largest letter, the B at the beginning of the

first psalm, the mass of colour is relieved by certain figures being cut

out in the block, which appear white in the impression. On the stem of

the letter a dog like a greyhound is seen chasing a bird; and flowers

and ears of corn are represented on the curved portions. These figures

being white, or the colour of the vellum, give additional brightness to

the full-bodied red by which they are surrounded, and materially add to

the beauty and effect of the whole letter.

In consequence of two blocks being required for each letter, the

166

means were afforded of printing any of them twice in the same sheet or

the same page with alternate colours; for while the body of the first

was printed in red from one block, the ornamental portion of the second

might be printed red at the same time from the other block. In the

second printing, with the blue colour, it would only be necessary to

transpose the blocks, and thus the two letters would be completed,

identical in shape and ornament, and differing only from the

corresponding portions being in the one letter printed red and in the

other blue. In the edition of 1459 the same ornamented letter is to be

found repeated on the same page; but of this I have only noticed one

instance; though there are several examples of the same letter being

printed twice in the same sheet.

Although the engraving of the most highly ornamented and largest of

those letters cannot be considered as an extraordinary instance of

skill, even at that period, for many wood-cuts of an earlier date afford

proof of greater excellence, yet the artist by whom the blocks were

engraved must have had considerable practice. The whole of the

ornamental part, which would be the most difficult to execute, is

clearly and evenly cut, and in some places with great neatness and

delicacy. “This letter,” says Heineken, “is an authentic testimony that

the artists employed on such a work were persons trained up and

exercised in their profession. The art of wood engraving was no longer

in its cradle.”

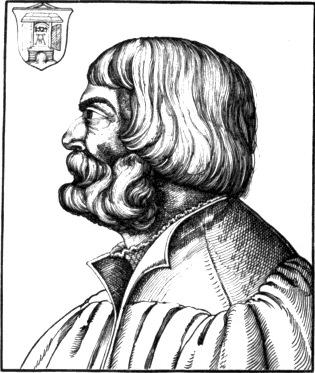

The name of the artist by whom those letters were engraved is

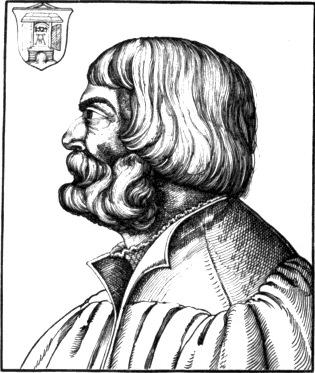

unknown. In Sebastian Munster’s Cosmography, book iii. chapter 159, John

Meydenbach is mentioned as being one of Gutemberg’s assistants; and an

anonymous writer in Serarius states the same fact. Heineken in noticing

these two passages writes to the following effect. “This Meydenbach is

doubtless the same person who proceeded with Gutemberg from Strasburg to

Mentz in 1444.IV.2 It is probable that he was a wood engraver or an

illuminator, but this is not certain; and it is still more uncertain

that this person engraved the cuts in a book entitled Apocalipsis cum

figuris, printed at Strasburg in 1502, because these are copied from

the cuts in the Apocalypse engraved and printed by Albert Durer at

Nuremberg. Whether this copyist was the Jacobus Meydenbach who

printed books at Mentz in 1491,IV.3 or he was some other engraver,

I have not been able to determine.”IV.4

167

Although so little is positively known respecting John Meydenbach,

Gutemberg’s assistant, yet Von Murr thinks that there is reason to

suppose that he was the artist who engraved the large initial letters

for the Psalter of 1457. Fischer, who declares that there is no

sufficient grounds for this conjecture, confidently assumes, from false

premises, that those letters were engraved by Gutemberg, “a person

experienced in such work,” adds he, “as we are taught by his residence

at Strasburg.” From the account that we have of his residence and

pursuits at Strasburg, however, we are taught no such thing. We only

learn from it he was engaged in some invention which related to

printing. We learn that Conrad Saspach made him a press, and it is

conjectured that the goldsmith Hanns Dunne was employed to engrave his

letters; but there is not a word of his being an experienced wood

engraver, nor is there a well authenticated passage in any account of

his life from which it might be concluded that he ever engraved a single

letter. Fischer’s reasons for supposing that Gutemberg engraved the

large letters in Faust and Scheffer’s Psalter are, however, contradicted

by facts. Having seen a few leaves of a Donatus ornamented with the same

initial letters as the Psalter, he directly concluded that the former

was printed by Gutemberg and Faust prior to the dissolution of their

partnership; and not satisfied with this leap he takes another, and

arrives at the conclusion that they were engraved by Gutemberg, as

“his modesty only could allow such works to appear without his

name.”

Although we have no information respecting the artist by whom those

letters were engraved, yet it is not unlikely that they were suggested,

if not actually drawn by Scheffer, who, from his profession of a scribe

or writerIV.5 previous to his connexion with Faust, may be

supposed to have been well acquainted with the various kinds of flowered

and ornamented capitals with which manuscripts of that and preceding

centuries were embellished. It is not unusual to find manuscripts of the

early part of the fifteenth century embellished with capitals of two

colours, red and blue, in the same taste as in the Psalter; and there is

now lying before me a capital P, drawn on vellum in red and blue ink, in

a manuscript apparently of the date of 1430, which is so like the same

letter in the Psalter that the one might be supposed to have suggested

the other.

It was an object with Faust and Scheffer to recommend their

Psalter—probably

168

the first work printed by them after Gutemberg had been obliged to

withdraw from the partnership—by the beauty of its capitals and

the sufficiency and distinctness of its “rubrications;”IV.6 and it is

evident that they did not fail in the attempt. The Psalter of 1457 is,

with respect to ornamental printing, their greatest work; for in no

subsequent production of their press does the typographic art appear to

have reached a higher degree of excellence. It may with truth be said

that the art of printing—be the inventor who he may—was

perfected by Faust and Scheffer; for the earliest known production of

their press remains to the present day unsurpassed as a specimen of

skill in ornamental printing.

A fac-simile of the large B at the commencement of the Psalter,

printed in colours the same as the original, is given in the first

volume of Dibdin’s Bibliotheca Spenceriana, and in Savage’s Hints on

Decorative Printing; but in neither of those works has the excellence of

the original letter been attained. In the Bibliotheca Spenceriana,

although the volume has been printed little more than twenty years, the

red colour in which the body of the letter is printed has assumed a

coppery hue, while in the original, executed nearly four hundred years

ago, the freshness and purity of the colours remain unimpaired. In

Savage’s work, though the letter and its ornaments are faithfully

copiedIV.7 and tolerably well printed, yet the colours are not

equal to those of the original. In the modern copy the blue is too

faint; and the red, which in the original is like well impasted paint,

has not sufficient body, but appears like a wash, through which in many

places the white paper may be seen. The whole letter compared with the

original seems like a water-colour copy compared with a painting in

oil.

Although it has been generally supposed that the art of printing was

first carried from Mentz in 1462 when Faust and Scheffer’s sworn workmen

were dispersedIV.8 on the capture of that city by the archbishop

169

Adolphus of Nassau, yet there can be no doubt that it was practised at

Bamberg before that period; for a book of fables printed at the latter

place by Albert Pfister is expressly dated on St. Valentine’s day, 1461;

and a history of Joseph, Daniel, Judith, and Esther was also printed by

Pfister at Bamberg in 1462, “Nit lang nach

sand walpurgen tag,”—not long after St. Walburg’s day.IV.9

It is therefore certain that the art was practised beyond Mentz previous

to the capture of that city, which was not taken until the eve of St.

Simon and St. Jude; that is, on the 28th of October in 1462. As it is

very probable that Pfister would have to superintend the formation of

his own types and the construction of his own presses,—for none of

his types are of the same fount as those used by Gutemberg or by Faust

and Scheffer,—we may presume that he would be occupied for some

considerable time in preparing his materials and utensils before he

could begin to print. As his first known work with a date, containing a

hundred and one wood-cuts, was finished on the 14th of February 1461, it

is not unlikely that he might have begun to make preparations three or

four years before. Upon these grounds it seems but reasonable to

conclude with Aretin, that the art was carried from Mentz by some of

Gutemberg and Faust’s workmen on the dissolution of their partnership in

1455; and that the date of the capture of Mentz—when for a time

all the male inhabitants capable of bearing arms were compelled to leave

the city by the captors—marks the period of its more general

diffusion. The occasion of the disaster to which Mentz was exposed for

nearly three years was a contest for the succession to the

archbishopric. Theodoric von Erpach having died in May 1459,

a majority of the chapter chose Thierry von Isenburg to succeed

him, while another party supported the pretensions of Adolphus of

Nassau. An appeal having been made to Rome, the election of Thierry was

annulled, and Adolphus was declared by the Pope to be the lawful

archbishop of Mentz. Thierry, being in possession and supported by the

citizens, refused to resign, until his rival, assisted by the forces of

his adherents and relations, succeeded in obtaining possession of the

city.IV.10

170

Until the discovery of Pfister’s book containing the four histories,

most bibliographers supposed that the date 1461, in the fables, related

to the composition of the work or the completion of the manuscript, and

not to the printing of the book. Saubert, who was the first to notice

it, in 1643, describes it as being printed, both text and figures, from

wood-blocks; and Meerman has adopted the same erroneous opinion.

Heineken was the first to describe it truly, as having the text printed

with moveable types, though he expresses himself doubtfully as to the

date, 1461, being that of the impression.

As the discovery of Pfister’s tracts has thrown considerable light on

the progress of typography and wood engraving, I shall give an

account of the most important of them, as connected with those subjects;

with a brief notice of a few circumstances relative to the early

connexion of wood engraving with the press, and to the dispersion of the

printers on the capture of Mentz in 1462.

The discovery of the history of Joseph, Daniel, Judith, and Esther,

with the date 1462, printed at Bamberg by Pfister, has established the

fact that the dates refer to the years in which the books were printed,

and not to the period when the works were composed or transcribed. An

account of the history above named, written by M. J. Steiner,

pastor of the church of St. Ulric at Augsburg, was first printed in

Meusel’s Historical and Literary Magazine in 1792; and a more ample

description of this and other tracts printed by Pfister was published by

Camus in 1800,IV.11 when the volume containing them, which was the

identical one that had been previously seen by Steiner, was deposited in

the National Library at Paris.

The book of fablesIV.12 printed by Pfister at Bamberg in 1461 is a

small folio consisting of twenty-eight leaves, and containing

eighty-five fables in rhyme in the old German language. As those fables,

which are ascribed to one “Boner, dictus der Edelstein,” are known to

have been written previous to 1330, the words at the end of the

volume,—“Zu Bamberg dies Büchlein geendet ist,”—At Bamberg

this book is finished,—most certainly relate to the time when it

was printed, and not when it was written. It is therefore the earliest

book printed with moveable types which is illustrated with wood-cuts

containing figures. Not having an opportunity of seeing this extremely

rare book,—of which only one perfect copy is known,—I am

unable to speak from personal examination of the style in which its

hundred and one cuts are engraved. Heineken,

171

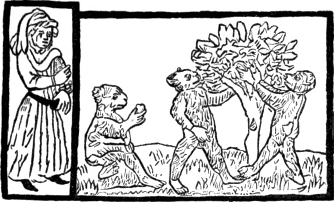

however, has given a fac-simile of the first, and he says that the

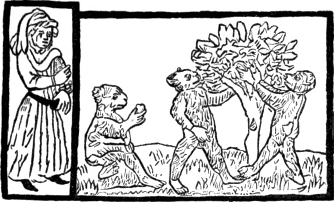

others are of a similar kind. The following is a reduced copy of the

fac-simile given by Heineken, and which forms the head-piece to the

first fable. On the manner in which it is engraved I shall make no

remark, until I shall have produced some specimens of the cuts contained

in a “Biblia Pauperum Predicatorum,” also printed by Pfister, and having

the text in the German language.

The volume described by Camus contains three different works; and

although Pfister’s name, with the date 1462, appears in only one of

them, the “Four Histories,” yet, as the type is the same in all, there

can be no doubt of the other two being printed by the same person and

about the same period. The following particulars respecting its contents

are derived from the “Notice” of Camus. It is a small folio consisting

altogether of a hundred and one leaves of paper of good quality,

moderately thick and white, and in which the water-mark is an ox’s head.

The text is printed in a large type, called missal-type; and though the

characters are larger, and there is a trifling variation in three or

four of the capitals, yet they evidently appear to have been copied from

those of the Mazarine Bible.

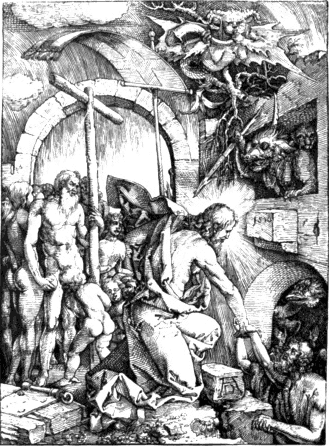

The first work is that which Heineken calls “une Allégorie sur la

Mort;”IV.13 but this title does not give a just idea of its

contents. It is in fact a collection of accusations preferred against

Death, with his answers to them. The object is to show that such

complaints are unavailing, and that, instead of making them, people

ought rather to employ themselves in endeavouring to live well. In this

tract, which

172

consists of twenty-four leaves, there are five wood-cuts, each occupying

an entire page. The first represents Death seated on a throne. Before

him there is a man with a child, who appears to accuse Death of having

deprived him of his wife, who is seen on a tomb wrapped in a

winding-sheet.—In the second cut, Death is also seen seated on a

throne, with the same person apparently complaining against him, while a

number of persons appear approaching sad and slow, to lay down the

ensigns of their dignity at his feet.—In the third cut there are

two figures of Death; one on foot mows down youths and maidens with a

scythe, while another, mounted, is seen chasing a number of figures on

horseback, at whom he at the same time discharges his arrows.—The

fourth cut consists of two parts, the one above the other. In the upper

part, Death appears seated on a throne, with a person before him in the

act of complaining, as in the first and second cuts. In the lower part,

to the left of the cut, is seen a convent, at the gate of which there

are two persons in religious habits; to the right a garden is

represented, in which are perceived a tree laden with fruit,

a woman crowning an infant, and another woman conversing with a

young man. In the space between the convent and the garden certain signs

are engraved, which Camus thinks are intended to represent various

branches of learning and science,—none of which can afford

protection against death,—as they are treated of in the chapter

which precedes the cut. In the fifth cut, Death and the Complainant are

seen before Christ, who is seated on a throne with an angel on each side

of him, under a canopy ornamented with stars. Although neither Heineken

nor Camus give specimens of those cuts, nor speak of the style in which

they are executed, it may be presumed that they are not superior either

in design or engraving to those contained in the other tracts.

The text of the work is divided into thirty-four chapters, each of

which, except the first, is preceded by a summary; and their numbers are

printed in Roman characters. The initial letter of each chapter is red,

and appears to have been formed by means of a stencil. The first

chapter, which has neither title nor numeral, commences with the

Complainant’s recital of his injuries; in the second, Death defends

himself; in the third the Complainant resumes, in the fourth Death

replies; and in this manner the work proceeds, the Complainant and Death

speaking alternately through thirty-two chapters. In the thirty-third,

God decides between the parties; and after a few common-place

reflections and observations on the readiness of people to complain on

all occasions, sentence is pronounced in these words: “The Complainant

is condemned, and Death has gained the cause. Of right, the Life of

every man is due to Death; to Earth his Body, and to Us his Soul.” In

the thirty-fourth chapter, the Complainant, perceiving that he has lost

his

173

suit, proceeds to pray to God on behalf of his deceased wife. In the

summary prefixed to the chapter the reader is informed that he is now

about to peruse a model of a prayer; and that the name of the

Complainant is expressed by the large red letters which are to be found

in the chapter. Accordingly, in the course of the chapter, six red

letters, besides the initial at the beginning, occur at the commencement

of so many different sentences. They are formed by means of a stencil,

while the letters at the commencement of other similar sentences are

printed black. Those red letters, including the initial at the beginning

of the chapter, occur in the following order, IHESANW. Whether the name

is expressed by them as they stand, or whether they are to be combined

in some other manner, Camus will not venture to decide.IV.14 From the

prayer it appears that the name of the Complainant’s deceased wife was

Margaret. In this singular composition, which in the summary is declared

to be a model, the author, not forgetting the court language of his

native country, calls the Almighty “the Elector who determines the

choice of all Electors,” “Hoffmeister” of the court of Heaven, and

“Herzog” of the Heavenly host. The text is in the German language, such

as was spoken and written in the fifteenth century.

The German words “Hoffmeister” and “Herzog” appear

extremely ridiculous in Camus’s French translation,—“le

Maître-d’hôtel de la cour céleste,” and “le Grand-duc de l’armée

céleste.” But this is clothing ancient and dignified German in modern

French frippery. The word “Hoffmeister”—literally, “court-master

or governor”—is used in modern German in nearly the same sense as

the English word “steward;” and the governor or tutor of a young prince

or nobleman is called by the same name. The word “Herzog”—the

“Grand-duc” of Camus—in its original signification means the

leader of a host or army. It is a German title of honour which defines

its original meaning, and is in modern language synonymous with the

English title “Duke.” The ancient German “Herzog” was a leader of hosts;

the modern French “Grand-duc” is a clean-shaved gentleman in a

court-dress, redolent of eau-de-Cologne, and bedizened with stars and

strings. The two words are characteristic of the two languages.

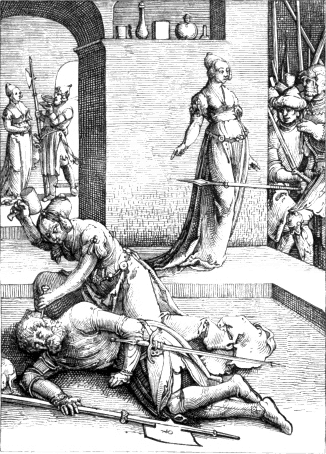

The second work in the volume is the Histories of Joseph, Daniel,

Judith, and Esther. It has no general frontispiece nor title; but each

separate history commences with the words: “Here begins the history

174

of . . . .” in German. Each history forms a separate

gathering, and the whole four are contained in sixty leaves, of which

two, about the middle, are blank, although there is no appearance of any

deficiency in the history. The text is accompanied with wood-cuts which

are much less than those in the “Complaints against Death,” each

occupying only the space of eleven lines in a page, which when full

contains twenty-eight. The number of the cuts is sixty-one; but there

are only fifty-five different subjects, four of them having been printed

twice, and one thrice. Camus gives a specimen of one of the cuts, which

represents the Jews of Bethuliah rejoicing and offering sacrifice on the

return of Judith after she had cut off the head of Holofernes. It is

certainly a very indifferent performance, both with respect to design

and engraving; and from Camus’s remarks on the artist’s ignorance and

want of taste it would appear that the others are no better. In one of

them Haman is decorated with the collar of an order from which a cross

is suspended; and in another Jacob is seen travelling to Egypt in a

carriageIV.15 drawn by two horses, which are harnessed according

to the manner of the fifteenth century, and driven by a postilion seated

on a saddle, and with his feet in stirrups. All the cuts in the “Four

Histories” are coarsely coloured.

It is this work which Camus, in his title-page, professes to give an

account of, although in his tract he describes the other two contained

in the same volume with no less minuteness. He especially announced a

notice of this work as “a book printed at Bamberg in 1462,” in

consequence of its being the most important in the volume; for it

contains not only the date and place, but also the printer’s name. In

the book of Fables, printed with the same types at Bamberg in 1461,

Pfister’s name does not appear.

The text of the “Four Histories” ends at the fourth line on the recto

of the sixtieth leaf; and after a blank space equal to that of a line,

thirteen lines succeed, forming the colophon, and containing the place,

date, and printer’s name. Although those lines run continuously on,

occupying the full width of the page as in prose, yet they consist of

couplets in German rhyme. The end of each verse is marked with a point,

and the first word of the succeeding one begins with a capital.

175

Camus has given a fac-simile of those lines, that he might at once

present his readers with a specimen of the type and a copy of this

colophon, so interesting to bibliographers as establishing the important

fact in the history of printing, namely, that the art was practised

beyond Mentz prior to 1462. The following copy, though not a fac-simile,

is printed line for line from Camus.

Ein ittlich mensch von herzen gert . Das er wer weiss

und wol gelert . An meister un’ schrift das nit mag

sein . So kun’ wir all auch nit latein . Darauff han

ich ein teil gedacht . Und vier historii zu samen pra-

cht . Joseph daniel un’ auch judith . Und hester auch

mit gutem sith. die vier het got in seiner hut . Als er

noch ye de’ guten thut . Dar durch wir pessern unser

lebe’ . De’ puchlein ist sein ende gebe’ . Tʒu bambergh

in der selbe’ stat . Das albrecht pfister gedrucket hat

Do ma’ zalt tausent un’ vierhu’dert iar . Im zwei und

sechzigste’ das ist war . Nit lang nach sand walpur-

gen tag . Die uns wol gnad erberben mag . Frid un’

das ewig lebe’ . Das wolle uns got alle’ gebe’ . Ame’.

The following is a translation of the above, in English couplets of

similar rhythm and measure as the original:

With heart’s desire each man doth seek

That he were wise and learned eke:

But books and teacher he doth need,

And all men cannot Latin read.

As on this subject oft I thought,

These hist’ries four I therefore wrote;

Of Joseph, Daniel, Judith too,

And Esther eke, with purpose true:

These four did God with bliss requite,

As he doth all who act upright.

That men may learn their lives to mend

This book at Bamberg here I end.

In the same city, as I’ve hinted,

It was by Albert Pfister printed,

In th’ year of grace, I tell you true,

A thousand four hundred and sixty-two;

Soon after good St. Walburg’s day,

Who well may aid us on our way,

And help us to eternal bliss:

God, of his mercy, grant us this. Amen.

The third work contained in the volume described by Camus is an

edition of the “Poor Preachers’ Bible,” with the text in German, and

176

printed on both sides. The number of the leaves is eighteen, of which

only seventeen are printed; and as there is a “history” on each page,

the total number in the work is thirty-four, each of which is

illustrated with five cuts. The subjects of those cuts and their

arrangement on the page is not precisely the same as in the earlier

Latin editions; and as in the latter there are forty “histories,” six

are wanting in the Bamberg edition, namely: 1. Christ in the

garden; 2. The soldiers alarmed at the sepulchre; 3. The Last

Judgment; 4. Hell; 5. The eternal Father receiving the

righteous into his bosom; and 6. The crowning of the Saints. As the

cuts illustrative of these subjects are the last in the Latin editions,

it is possible that the Bamberg copy described by Camus might be

defective; he, however, observes that there is no appearance of any

leaves being wanting.IV.16 In each page of the Bamberg edition the

text is in two columns below the cuts, which are arranged in the

following manner in the upper part of the page:

|

3

Christ appearing to the Apostles. |

|

1

Busts. |

2

Busts. |

4

Joseph making himself known to his brethern. |

5

The Prodigal Son’s return to his father. |

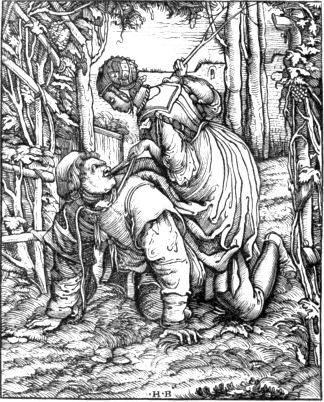

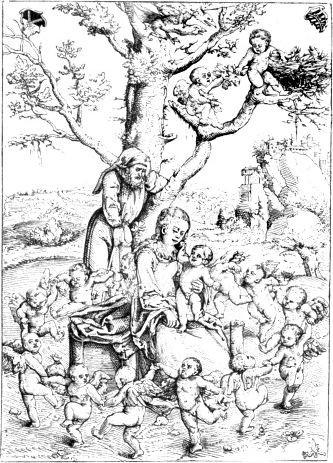

The following cuts are fac-similes of those given by Camus; and the

numbers underneath each relate to their position in the preceding

177

example of their arrangement. In No. 1 the heads are intended for

David and the author of the Book of Wisdom; in No. 2, for Isaiah

and Ezekiel.

No. 1.

No. 2.

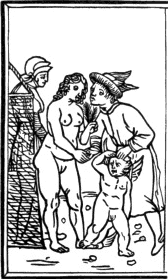

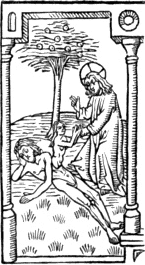

The subject represented in the following cut, No. 3, forming the

centre piece at the top in the arrangement of the original page, is

Christ appearing to his disciples after his resurrection. The figure on

the right of Christ is intended for St. Peter, and that on his left for

St. John. I believe that in no wood-cut, ancient or modern, is

Christ represented with so uncomely an aspect and so clumsy a

figure.

No. 3.

The subject of No. 4 is Joseph making himself known to his brethren;

from Genesis, chapter XLV.

178

No. 4.

In No. 5 the subject represented is the Prodigal Son received by his

father; from St. Luke, chapter XV.

Camus says that the cuts given by him were engraved on wood by Duplaa

with the greatest exactitude from tracings of the originals by

Dubrena.

No. 5.

Supposing that all the cuts in the four works, printed by Pfister and

described in the preceding pages, were designed in a similar taste and

executed in a similar manner to those of which specimens are given, the

persons by whom they were engraved—for it is not likely that they

were

179

all engraved by one man—must have had very little knowledge of the

art. Looking merely at the manner in which they are engraved, without

reference to the wretched drawing of the figures and want of “feeling”

displayed in the general treatment of the subjects, a moderately

apt lad, at the present day, generally will cut as well by the time that

he has had a month or two’s practice. If those cuts were to be

considered as fair specimens of wood engraving in Germany in 1462, it

would be evident that the art was then declining; for none of the

specimens that I have seen of the cuts printed by Pfister can bear a

comparison with those contained in the early block-books, such as the

Apocalypse, the History of the Virgin, or the early editions of the Poor

Preachers’ Bible. To the cuts contained in the latter works they are

decidedly inferior, both with respect to design and engraving. Even the

earliest wood-cuts which are known,—for instance, the St.

Christopher, the St. Bridget, and the Annunciation, in Earl Spencer’s

collection,—are executed in a superior manner.

It would, however, be unfair to conclude that the cuts which appear

in Pfister’s works were the best that were executed at that period. On

the contrary, it is probable that they are the productions of persons

who in their own age would be esteemed only as inferior artists. As the

progress of typography was regarded with jealousy by the early wood

engravers and block printers, who were apprehensive that it would ruin

their trade, and as previous to the establishment of printing they were

already formed into companies or fellowships, which were extremely

sensitive on the subject of their exclusive rights, it is not unlikely

that the earliest type-printers who adorned their books with wood-cuts

would be obliged to have them executed by a person who was not

professionally a wood engraver. It is only upon this supposition that we

can account for the fact of the wood-cuts in the earliest books printed

with type being so very inferior to those in the earliest block-books.

This supposition is corroborated by the account which we have of the

proceedings of the wood engravers of Augsburg shortly after

type-printing was first established in that city. In 1471 they opposed

Gunther Zainer’sIV.17 admission to the privileges of a burgess, and

endeavoured to prevent him printing wood engravings in his books.

180

Melchior Stamham, however, abbot of St. Ulric and Afra, a warm

promoter of typography, interested himself on behalf of Zainer, and

obtained an order from the magistracy that he and John

Schussler—another printer whom the wood engravers had also

objected to—should be allowed to follow without interruption their

art of printing. They were, however, forbid to print initial letters

from wood-blocks or to insert wood-cuts in their books, as this would be

an infringement on the privileges of the fellowship of wood engravers.

Subsequently the wood engravers came to an understanding with Zainer,

and agreed that he should print as many initial letters and wood-cuts as

he pleased, provided that they engraved them.IV.18 Whether Schussler

came to the same agreement or not is uncertain, as there is no book

known to be printed by him of a later date than 1472. It is probable

that he is the person,—named John Schüssler in the

memorandum printed by Zapf,—of whom Melchior de Stamham in that

year bought five presses for the printing-office which he established in

his convent of St. Ulric and St. Afra. To John Bämler, who at the same

time carried on the business of a printer at Augsburg, no objection

appears to have been made. As he was originally a “calligraphus” or

ornamental writer, it is probable that he was a member of the wood

engravers’ guild, and thus entitled to engrave and print his own works

without interruption.

As it is probable that the wood-cuts which appear in books printed

within the first thirty years from the establishment of typography at

Mentz were intended to be coloured, this may in some degree account for

the coarseness with which they are engraved; but as the wood-cuts in the

earlier block-books were also intended to be coloured in a similar

manner, the inferiority of the former can only be accounted for by

supposing that the best wood engravers declined to assist in promoting

what they would consider to be a rival art, and that the earlier

printers would generally be obliged to have their cuts engraved by

persons connected with their own establishments, and who had not by a

regular course of apprenticeship acquired a knowledge of the art. About

seventy or eighty years ago, and until a more recent period, many

country printers in England used themselves to engrave such rude

wood-cuts as they might occasionally want. A most extensive

assortment of such wood-cuts belonged to the printing-office of the late

Mr. George Angus of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, who used them as head-pieces

and general illustrations to ballads and chap-books. A considerable

number of them were cut with a penknife, on pear-tree wood, by an

apprentice named Randell, who died about forty years ago.

181

Persons who are fond of a “rough harvest” of such modern-antiques are

referred to the “Historical Delights,” the “History of Ripon,” and other

works published by Thomas Gent at York about 1733.

Notwithstanding the rudeness with which the cuts are engraved in the

four works printed by Pfister, yet from their number a considerable

portion of time must have been occupied in their execution. In the “Four

Histories” there are sixty-one cuts, which have been printed from

fifty-five blocks. In the “Fables” there are one hundred and one cuts;

in the “Complaints against Death,” five; and in the “Poor Preachers’

Bible,” one hundred and seventy, reckoning each subject separately.

Supposing each cut in the three last works was printed from a

separate block, the total number of blocks required for the four

would be three hundred and thirty-one.IV.19 Supposing that each cut on

an average contained as much work as that which is numbered 4 in the

preceding specimens—Joseph making himself known to his

brethren—and supposing that the artist drew the subjects himself,

the execution of those three hundred and thirty-one cuts would occupy

one person for about two years and a half, allowing him to work three

hundred days in each year. It is true that a modern wood engraver might

finish more than three of such cuts in a week, yet I question if any one

of the profession would complete the whole number, with his own hands,

in less time than I have specified.

From the similarity between Pfister’s types and those with which a

Bible without place or date is printed, several bibliographers have

ascribed the latter work to his press. This Bible, which in the Royal

Library at Paris is bound in three volumes folio, is the rarest of all

editions of the Scriptures printed in Latin. Schelhorn, who wrote a

dissertation on this edition, endeavoured to show that it was the first

of the Bibles printed at Mentz, and that it was partly printed by

Gutemberg and Faust previous to their separation, and finished by Faust

and Scheffer in 1456.IV.20 Lichtenberger, without expressly assenting

to Schelhorn’s opinion, is inclined to think that it was printed at

Mentz, and by Gutemberg. The reasons which he assigns, however, are not

such as are likely to gain assent without a previous willingness to

believe. He admits that Pfister’s types are similar to those of the

Bible, though he says that the former are somewhat ruder.

182

Camus considers that the tracts unquestionably printed by Pfister

throw considerable light on the question as to whom this Bible is to be

ascribed. There are two specimens of this Bible, the one given by Masch

in his Bibliotheca Sacra, and the other by Schelhorn, in a dissertation

prefixed to Quirini’s account of the principal works printed at Rome.

Camus, on comparing these specimens with the text of Pfister’s tracts,

immediately perceived the most perfect resemblance between the

characters; and on applying a tracing of the last thirteen lines of the

“Four Histories” to the corresponding letters in Schelhorn’s specimen,

he found that the characters exactly corresponded. This perfect identity

induced him to believe that the Bible described by Schelhorn was printed

with Pfister’s types. A correspondent in Meusel’s Magazine, No.

VII. 1794, had previously advanced the same opinion; and he moreover

thought that the Bible had been printed previous to the Fables dated

1461, because the characters of the Bible are cleaner, and appear as if

they had been impressed from newer types than those of the Fables.IV.21 In support of this opinion an extract is given, in

the same magazine, from a curious manuscript of the date of 1459, and

preserved in the library of Cracow. This manuscript is a kind of

dictionary of arts and sciences, composed by Paul of Prague, doctor of

medicine and philosophy, who, in his definition of the word

“Libripagus,” gives a curious piece of information to the following

effect. The barbarous Latin of the original passage, to which I shall

have occasion to refer, will be found in the subjoined note.IV.22 “He

is an artist who dexterously cuts figures, letters, and whatever he

pleases on plates of copper, of iron, of solid blocks of wood, and other

materials, that he may print upon paper, on a wall, or on a clean board.

He cuts whatever he pleases; and he proceeds in this manner with respect

to pictures. In my time somebody of Bamberg cut the entire Bible upon

plates; in four weeks he impressed the whole Bible, thus sculptured,

upon thin parchment.”

Although I am of opinion that the weight of evidence is in favour of

Pfister being the printer of the Bible in question, yet I cannot think

that the arguments which have been adduced in his favour derive any

additional support from this passage. The writer, like many other

dictionary makers, both in ancient and modern times, has found it a more

difficult matter to give a clear account of a thing than to find

the

183

synonym of a word. But, notwithstanding his confused account,

I think that I can perceive in it the “disjecta membra” of an

ancient Formschneider and a Briefmaler, but no indication of a

typographer.

In a jargon worthy of the “Epistolæ obscurorum virorum” he describes

an artist, or rather an artizan, “sculpens subtiliter in laminibusIV.23 [laminis] æreis, ferreis, ac ligneis solidi ligni,

atque aliis, imagines, scripturam et omne quodlibet.” In this passage

the business of the “Formschneider” may be clearly enough distinguished:

he cuts figures and animals in plates of copper and iron;—but not

in the manner of a modern copper-plate engraver; but in the manner in

which a stenciller pierces his patterns. That this is the true meaning

of the writer is evident from the context, wherein he informs us of the

artist’s object in cutting such letters and figures, namely, “ut prius

imprimat papyro aut parieti aut asseri mundo,”—that he may print

upon paper, on a wall, or on a clean board. This is evidently

descriptive of the practice of stencilling, and proves, if the

manuscript be authentic, that the old “Briefmalers” were accustomed to

“slapdash” walls as well as to engrave and colour cards. In the

distinction which is made of the “laminibus ligneis ligni

solidi,” it is probable that the writer meant to specify the

difference between cutting out letters and figures on thin plates of

metal, and cutting upon blocks of solid wood. When he speaks of a

Bible being cut, at Bamberg, “super lamellas,” he most likely means a

“Poor Preachers’ Bible,” engraved on blocks of wood. An impression of a

hundred or more copies of such a work might easily enough be taken in a

month when the blocks were all ready engraved; but we cannot suppose

that the Bible ascribed to Pfister could be worked off in so short a

time. This Bible consists of eight hundred and seventy leaves; and to

print an edition of three hundred copies at the rate of three hundred

sheets a day would require four hundred and fifty days. About three

hundred copies of each work appears to have been the usual number which

Sweinheim and Pannartz and Ulric Hahn printed, on the establishment of

the art in Italy; and Philip de Lignamine in his chronicle mentions,

under the year 1458, that Gutemberg and Faust, at Mentz, and Mentelin at

Strasburg, printed three hundred sheets in a day.IV.24

Of Pfister nothing more is positively known than what the tracts

printed by him afford; namely, that he dwelt at Bamberg, and exercised

the business of a printer there in 1461 and 1462. He might indeed print

there both before and after those years, but of this we have no direct

184

evidence. From 1462 to 1481 no book is known to have been printed at

Bamberg. In the latter year, a press was established there by John

Sensenschmidt of Egra, who had previously, that is from 1470, printed

several works at Nuremberg.

Panzer, alluding to Pfister as the printer only of the Fables and of

the tracts contained in the volume described by Camus, says that he can

scarcely believe that he had a fixed residence at Bamberg; and that

those tracts most likely proceeded from the press of a travelling

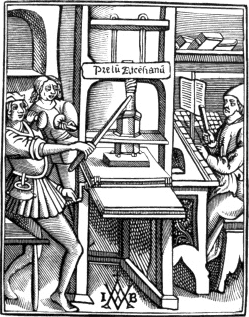

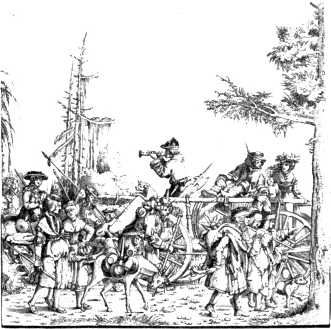

printer.IV.25 Several of the early printers, who commenced on

their own account, on the dispersion of Faust and Scheffer’s workmen in

1462, were accustomed to travel with their small stock of materials from

one place to another; sometimes finding employment in a monastery, and

sometimes taking up their temporary abode in a small town; removing to

another as soon as public curiosity was satisfied, and the demand for

the productions of their press began to decline. As they seldom put

their names, or that of the place, to the works which they printed, it

is extremely difficult to decide on the locality or the date of many old

books printed in Germany. It is very likely that they were their own

letter-founders, and that they themselves engraved such wood-cuts as

they might require. As their object was to gain money, it is not

unlikely that they might occasionally sell a portion of their types to

each other;IV.26 or to a novice who wished to begin the business,

or to a learned abbot who might be desirous of establishing an amateur

press within the precinct of his monastery, where copies of the Facetiæ

of Poggius might be multiplied as well as the works of St. Augustine.

Although it has been asserted the monks regarded with jealousy the

progress of printing, as if it were likely to make knowledge too cheap,

and to interfere with a part of their business as transcribers of books,

such does not appear to have been the fact. In every country in Europe

we find them to have been the first to encourage and promote the new

art; and the annals of typography most clearly show that the greater

part of the books printed within the first thirty years from the time of

Gutemberg and Faust’s partnership were chiefly for the use of the monks

and the secular clergy.

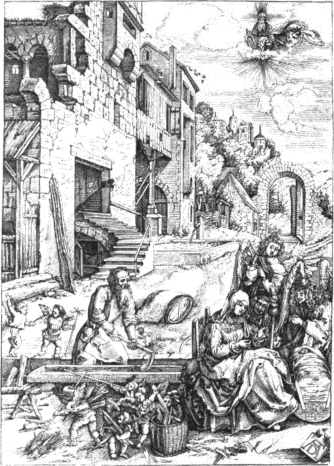

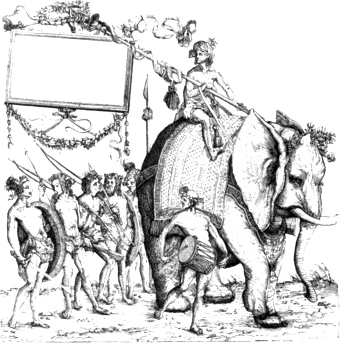

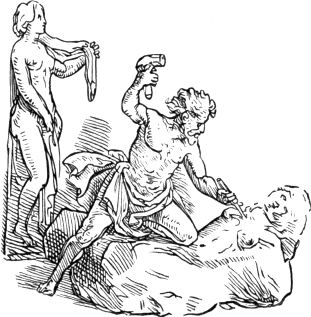

From 1462 to 1467 there appears to have been no book printed

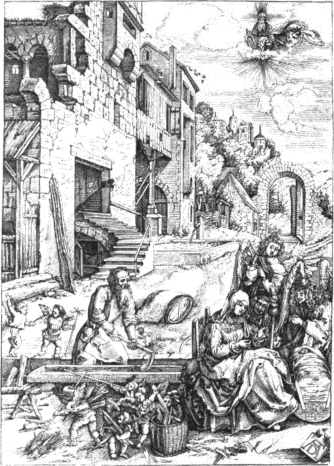

containing wood-cuts. In the latter year Ulric Hahn, a German,

printed at Rome a book entitled “Meditationes Johannis de

Turrecremata,”IV.27 which

185

contains wood-cuts engraved in simple outline in a coarse manner. The

work is in folio, and consists of thirty-four leaves of stout paper, on

which the water-mark is a hunter’s horn. The number of cuts is also

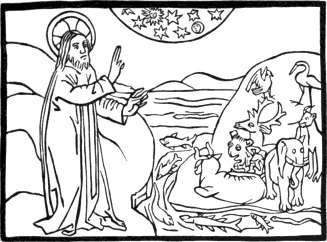

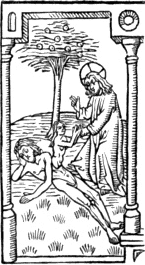

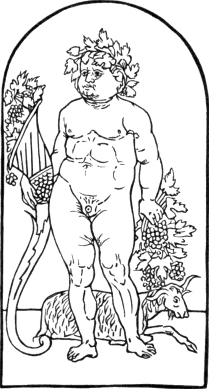

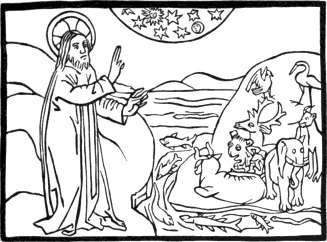

thirty-four; and the following—the creation of animals—is a

reduced copy of the first.

The remainder of the cuts are executed in a similar style; and though

designed with more spirit than those contained in Pfister’s tracts, yet

it can scarcely be said that they are better engraved. The following is

an enumeration of the subjects. 1. The Creation, as above

represented. 2. The Almighty speaking to Adam. 3. Eve taking

the apple. (From No. 3 the rest of the cuts are illustrative of the

New Testament or of Ecclesiastical History.) 4. The Annunciation.

5. The Nativity. 6. Circumcision of Christ. 7. Adoration

of the Magi. 8. Simeon’s Benediction. 9. The Flight into

Egypt. 10. Christ disputing with the Doctors in the Temple.

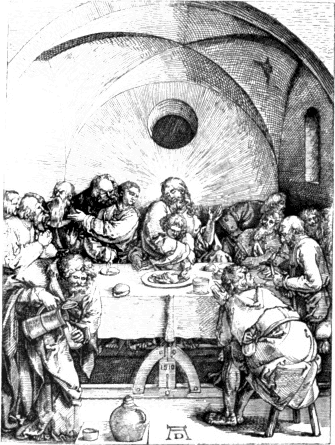

11. Christ baptized. 12. The Temptation in the Wilderness.

13. The keys given to Peter. 14. The Transfiguration.

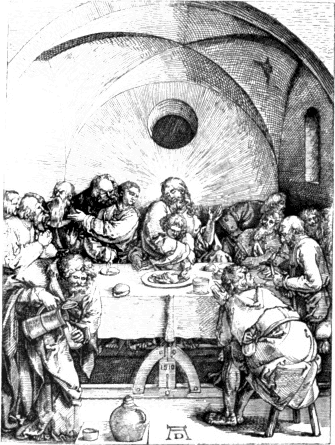

15. Christ washing the Apostles’ feet. 16. The Last Supper.

17. Christ betrayed by Judas. 18. Christ led before the High

Priest. 19. The Crucifixion. 20. Mater Dolorosa. 21. The

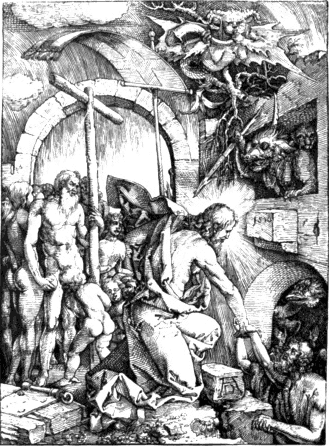

Descent into Hell. 22. The Resurrection. 23. Christ appearing

to his Disciples. 24. The Ascension. 25. The feast of

Pentecost 26. The Host borne by a bishop. 27. The mystery of

the Trinity; Abraham sees three and adores one. 28. St. Dominic

extended like the “Stam-Herr” or first ancestor in a pedigree,

and sending forth

186

numerous branches as Popes, Cardinals, and Saints. 29. Christ

appearing to St. Sixtus. 30. The Assumption of the Virgin.

31. Christ seated amidst a choir of Angels. 32. Christ seated

at the Virgin’s right hand in the assembly of Saints. 33. The

Office of Mass for the Dead. 34. The Last Judgment.

Zani says that those cuts were engraved by an Italian artist, but

beyond his assertion there is no authority for the fact. It is most

likely that they were cut by one of Hahn’s workmen, who could

occasionally “turn his hand” to wood-engraving and type-founding, as

well as compose and work at press; and it is most probable that Hahn’s

workmen when he first established a press in Rome were Germans, and not

Italians.

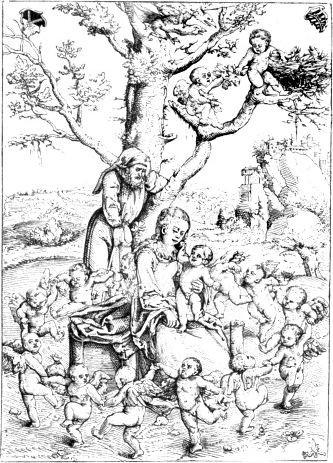

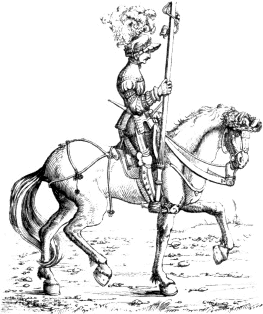

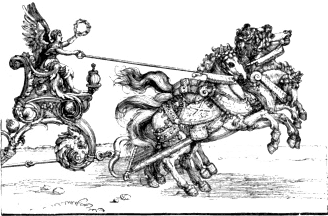

The second book printed in Italy with wood-cuts is the “Editio

Princeps” of the treatise of R. Valturius de Re Militari, which

appeared at Verona from the press of “Johannes de Verona,” son of

Nicholas the surgeon, and master of the art of printing.IV.28 This work

is dedicated by the author to Sigismund Malatesta, lord of Rimini, who

is styled in pompous phrase, “Splendidissimum Arminensium Regem ac

Imperatorem semper invictum.” The work, however, must have been written

several years before it was printed, for Baluze transcribed from a MS.

dated 1463 a letter written in the name of Malatesta, and sent by the

author with a copy of his work to the Sultan Mahomet II. The bearer of

this letter was the painter Matteo Pasti, a friend of the author,

who visited Constantinople at the Sultan’s request in order that he

might paint his portrait. It is said that the cuts in this work were

designed by Pasti; and it is very probable that he might make the

drawings in Malatesta’s own copy, from which it is likely that the book

was printed. As Valturius has mentioned Pasti as being eminently skilful

in the arts of Painting, Sculpture, and Engraving,IV.29

Maffei has conjectured,—and Mr. Ottley adds, “with some appearance

of probability,”—that the cuts in question were executed by his

hand. If such were the fact, it only could be regretted that an artist

so eminent should have mis-spent his time in a manner so unworthy of his

reputation; for, allowing that a considerable degree of talent is

displayed in many of the designs, there is nothing in the engraving, as

they are mere outlines, but what might be cut by a novice. There is not,

however, the slightest reasonable ground to suppose that those

engravings were cut by Matteo Pasti, for I believe that he died before

printing was introduced into Italy; and it surely would be

187

presuming beyond the verge of probability to assert that they might be

engraved in anticipation of the art being introduced, and of the book

being printed at some time or other, when the blocks would be all ready

engraved, in a simple style of art indeed, but with a master’s hand.

A master-sculptor’s hand, however, is not very easily distinguished

in the mere rough-dressing of a block of sandstone, which any country

mason’s apprentice might do as well. It is very questionable if Matteo

Pasti was an engraver in the present sense of the word; the engraving

meant by Valturius was probably that of gold and silver vessels and

ornaments; but not the engraving of plates of copper or other metal for

the purpose of being printed.

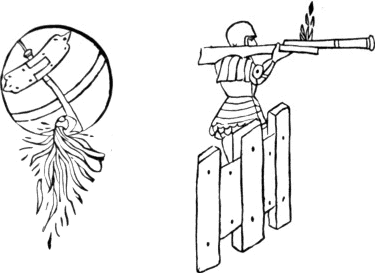

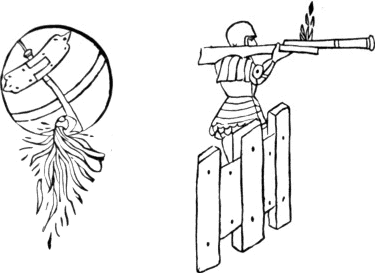

Several of those cuts occupy an entire folio page, though the greater

number are of smaller size. They chiefly represent warlike engines,

which display considerable mechanical skill on the part of the

contriver; modes of attack and defence both by land and water, with

various contrivances for passing a river which is not fordable, by means

of rafts, inflated bladders, and floating bridges. In some of them

inventions may be noticed which are generally ascribed to a later

period: such as a boat with paddle-wheels, which are put in motion by a

kind of crank; a gun with a stock, fired from the shoulder; and a

bomb-shell. It has frequently been asserted that hand-guns were first

introduced about the beginning of the sixteenth century, yet the figure

of one in the work of Valturius makes it evident that they were known

some time before. It is also likely that the drawing was made and the

description written at least ten years before the book was printed. It

has also been generally asserted that bomb-shells were first used by

Charles VIII. of France when besieging Naples in 1495. Valturius,

however, in treating of cannon, ascribes the invention to Malatesta.IV.30 Gibbon, in chapter lxviii. of his History of the

Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, notices this cut of a bomb-shell.

His reference is to the second edition of the work, in Italian, printed

also at Verona by Bonin de Bononis in 1483, with the same cuts as the

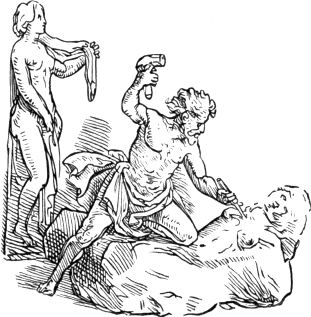

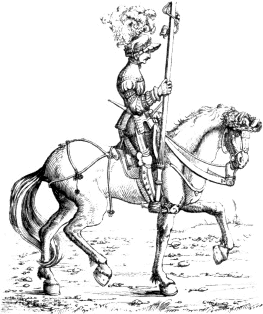

first edition in Latin.IV.31 The two following cuts are fac-similes of

the bomb-shell and the hand-gun, as represented in the edition of 1472.

The figure armed with the gun,—a portion of a

188

large cut,—is firing from a kind of floating battery; and in the

original two figures armed with similar weapons are stationed

immediately above him.

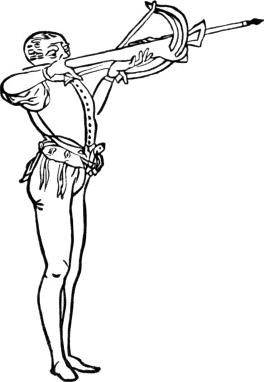

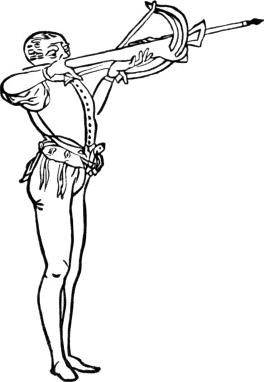

The following fac-simile of a cut representing a man shooting with a

cross-bow is the best in the book. The drawing of the figure is good,

and the attitude graceful and natural. The figure, indeed, is not only

the best in the work of Valturius, but is one of the best, so far as

respects the drawing, that is to be met with in any book printed in the

fifteenth century.

The practice of introducing wood-cuts into printed books seems to

have been first generally adopted at Augsburg, where Gunther Zainer, in

1471, printed a German translation of the “Legenda Sanctorum” with

figures of the saints coarsely engraved on wood. This, I believe,

is the first book, after Pfister’s tracts, printed in Germany with

wood-cuts and containing a date. In 1472 he printed a second volume of

the same work, and an edition of the book entitled “Belial,”IV.32 both

containing wood-cuts. Several other works printed by him between 1471

and 1475 are illustrated in a similar manner. Zainer’s example was

followed at Augsburg by his contemporaries John Bämler and John

Schussler;

189

and by them, and Anthony Sorg, who first began to print there about

1475, more books with wood-cuts were printed in that city previous to

1480 than at any other place within the same period. In 1477 the first

German Bible with wood-cuts was printed by Sorg, who printed another

edition with the same cuts and initial letters in 1480. In 1483 he

printed an account of the Council of Constance held in 1431, with

upwards of a thousand wood-cuts of figures and of the arms of the

principal persons both lay and spiritual who attended the council. Upon

this work Gebhard, in his Genealogical History of the Heritable States

of the German Empire, makes the following observations:—“The first

printed collection of arms is that of 1483 in the History of the Council

of Constance written by Ulrich Reichenthal. To this council we are

indebted accidentally for the collection. From the thirteenth century it

was customary to hang up the shields of noble and honourable persons

deceased in churches; and subsequently the practice was introduced of

painting them upon the walls, or of placing them in the windows in

stained glass. A similar custom prevailed at the Council of

Constance; for every person of consideration who attended

190

had his arms painted on the wall in front of his chamber; and thus

Reichenthal, who caused those arms to be copied and engraved on wood,

was enabled to give in his history the first general collection of

coat-armour which had appeared; as eminent persons from all the Catholic

states of Europe attended this council.”IV.33

The practice of introducing wood-cuts became in a few years general

throughout Germany. In 1473, John Zainer of Reutlingen, who is said to

have been the brother of Gunther, printed an edition of Boccacio’s work

“De mulieribus claris,” with wood-cuts, at Ulm. In 1474 the first

edition of Werner Rolewinck de Laer’s chronicle, entitled “Fasciculus

Temporum,” was printed with wood-cuts by Arnold Ther-Hoernen at Cologne;

and in 1476 an edition of the same work, also with wood-cuts, was

printed at Louvain by John Veldener, who previously had been a printer

at Cologne. In another edition of the same work printed by Veldener at

Utrecht in 1480, the first page is surrounded with a border of foliage

and flowers cut on wood; and another page, about the middle of the

volume, is ornamented in a similar manner. These are the earliest

instances of ornamental borders from wood-blocks which I have observed.

About the beginning of the sixteenth century title-pages surrounded with

ornamental borders are frequent. From the name of those borders,

Rahmen, the German wood engravers of that period are sometimes

called Rahmenschneiders. Prosper Marchand, in his “Dictionnaire

Historique,” tom. ii. p. 156, has stated that Erhard Ratdolt,

a native of Augsburg, who began to print at Venice about 1475, was

the first printer who introduced flowered initial letters, and

vignettes—meaning by the latter term wood-cuts; but his

information is scarcely correct. Wood-cuts—without reference to

Pfister’s tracts, which were not known when Marchand wrote—were

introduced at Augsburg six years before Ratdolt and his partnersIV.34

printed at Venice in 1476 the “Calendarium Joannis Regiomontani,” the

work to which Marchand alludes. It may be true that he introduced a new

kind of initial letters ornamented with flowers in this work, but much

more beautiful initial letters had appeared long before in the Psalter,

in the “Durandi Rationale,” and the “Donatus” printed by Faust and

Scheffer. The first person who mentions Ratdolt as the inventor of

“florentes litteræ,” so named from the flowers with which they are

intermixed, is Maittaire, in his Annales Typographici, tom. i. part

i. p. 53.

191

In 1483 Veldener,IV.35 as has been previously observed at page

106, printed at Culemburg an edition in small quarto of the Speculum

Salvationis, with the same blocks as had been used in the earlier folio

editions, which are so confidently ascribed to Lawrence Coster. In

Veldener’s edition each of the large blocks, consisting of two

compartments, is sawn in two in order to adapt them to a smaller page.

A German translation of the Speculum, with wood-cuts, was printed

at Basle, in folio, in 1476; and Jansen says that the first book printed

in France with wood-cuts was an edition of the Speculum, at Lyons, in

1478; and that the second was a translation of the book named “Belial,”

printed at the same place in 1482.

The first printed book in the English language that contains

wood-cuts is the second edition of Caxton’s “Game and Playe of the

Chesse,” a small folio, without date or place, but generally

supposed to have been printed about 1476.IV.36 The first edition

of the same work, without cuts, was printed in 1474. On the blank leaves

at the end of a copy of the first edition in the King’s Library, at the

British Museum, there is written in a contemporary hand a list of the

bannerets and knightsIV.37 made at the battle of “Stooke by syde

newerke apon trent the xvi day of june the iide yer of harry

the vii.” that is, in 1487. In this battle Martin Swart was killed. He

commanded the Flemings, who were sent by the Duchess of Burgundy to

assist Lambert Simnel. It was at the request of the duchess, who was

Edward the Fourth’s sister, that Caxton translated the “Recuyell of the

Historyes of Troye,” the first book printed in the English language, and

which appeared at Cologne in 1471 or 1472.

In Dr. Dibdin’s edition of Ames’s Typographical Antiquities there is

a “Description of the Pieces and Pawns” in the second edition of

Caxton’s Chess; which description is said to be illustrated with

facsimile

192

wood-cuts. There are indeed fac-similes of some of the figures given,

but not of the wood-cuts generally; for in almost every cut given by Dr.

Dibdin the back-ground of the original is omitted. In the description of

the first fac-simile there is also an error: it is said to be “the

first cut in the work,” while in fact it is the second.

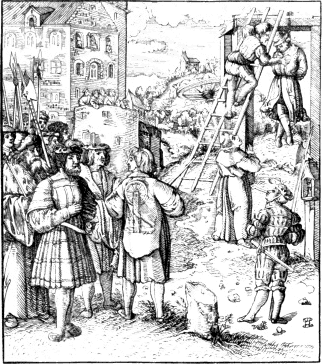

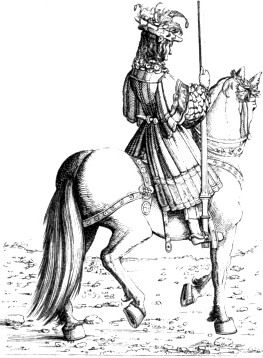

The following I believe to be a correct list of these first fruits of

English wood-engraving.

1. An executioner with an axe cutting to pieces, on a block, the

limbs of a man. On the head, which is lying on the ground, there is a

crown. Birds are seen seizing and flying away with portions of the

limbs. There are buildings in the distance, and three figures, one of

whom is a king with a crown and sceptre, appear looking on. 2. A

figure sitting at a table, with a chess-board before him, and holding

one of the chess-men in his hand. This is the cut which Dr. Dibdin says

is the first in the book. 3. A king and another person playing at

chess. 4. The king at chess, seated on a throne. 5. The king

and queen. 6. The “alphyns,” now called “bishops” in the game of

chess, “in the maner of judges sittyng.” 7. The knight. 8. The

“rook,” or castle, a figure on horseback wearing a hood and holding

a staff in his hand. From No. 9 to No. 15 inclusive, the pawns

are thus represented. 9. Labourers and workmen, the principal

figure representing the first pawn, with a spade in his right hand and a

cart-whip in his left. 10. The second pawn, a smith with his

buttriss in the string of his apron, and a hammer in his right hand.

11. The third pawn, represented as a clerk, that is a writer

or transcriber, in the same sense as Peter Scheffer and Ulric Zell are

styled clerici, with his case of writing materials at his girdle,

a pair of shears in one hand, and a large knife in the other. The

knife, which has a large curved blade, appears more fit for a butcher’s

chopper than to make or mend pens. 12. The fourth pawn, a man

with a pair of scales, and having a purse at his girdle, representing

“marchauntes or chaungers.” 13. The fifth pawn, a figure

seated on a chair, having in his right hand a book, and in his left a

sort of casket or box of ointments, representing a physician, spicer, or

apothecary. 14. The sixth pawn, an innkeeper, receiving a guest.

15. The seventh pawn, a figure with a yard measure in his

right hand, a bunch of keys in his left, and an open purse at his

girdle, representing “customers and tolle gaderers.” 16. The eighth

pawn, a figure with a sort of badge on his breast near to his right

shoulder, after the manner of a nobleman’s retainer, and holding a pair

of dice in his left hand, representing dice-players, messengers, and

“currours,” that is “couriers.” In old authors the numerous idle

retainers of the nobility are frequently represented as gamblers,

swash-bucklers, and tavern-haunters.

Although there are twenty-four impressions in the volume, yet there

are only sixteen subjects, as described above; the remaining eight being

193

repetitions of the cuts numbered 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 10, with two

impressions of the cut No. 2, besides that towards the

commencement.

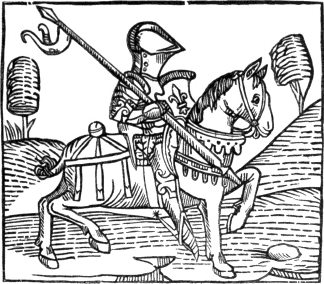

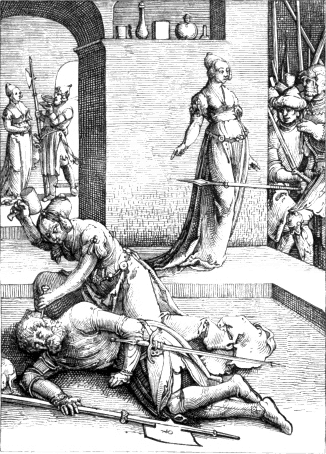

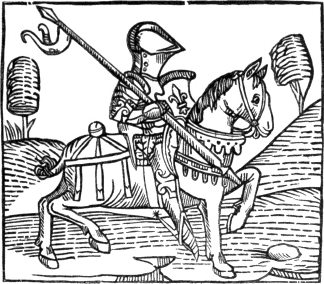

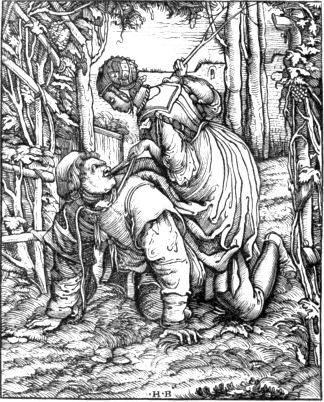

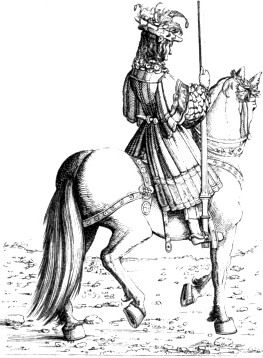

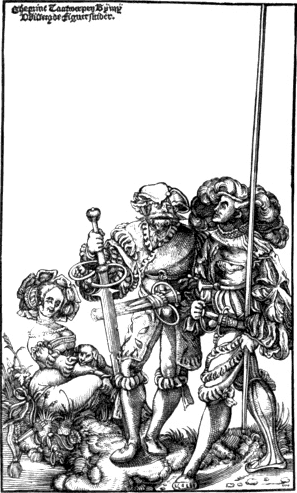

The above cut is a reduced copy of the knight, No. 7; and his

character is thus described: “The knyght ought to be maad al armed upon

an hors in suche wise that he have an helme on his heed and a spere in

his right hond, and coverid with his shelde, a swerde and a mace on

his left syde . clad with an halberke and plates tofore his breste .

legge harnoys on his legges . spores on his heelis, on hys handes hys

gauntelettes . hys hors wel broken and taught and apte to bataylle and

coveryd with hys armes. When the Knyghtes been maad they ben bayned or

bathed . That is the signe that they sholde lede a newe lyf and newe

maners . also they wake alle the nyght in prayers and orisons unto god

that he wil geve hem grace that they may gete that thyng that they may

not gete by nature. The kyng or prynce gyrdeth a boute them a swerde in

signe that they shold abyde and kepen hym of whom they taken their

dispences and dignyte.”

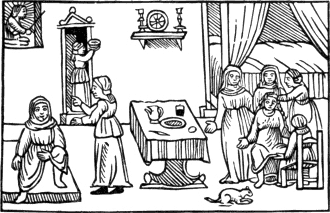

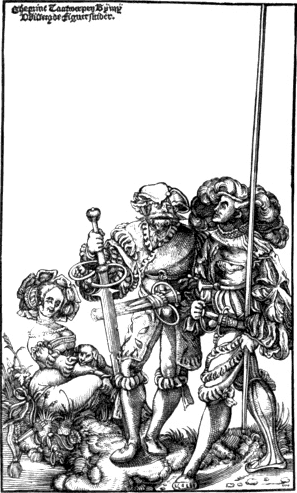

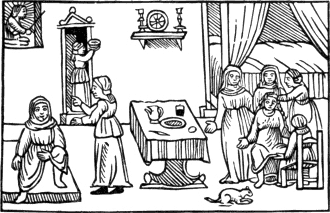

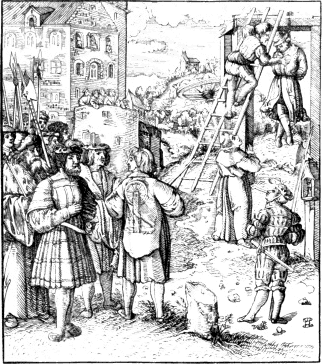

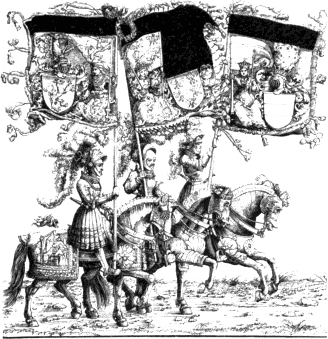

The following cut of the sixth or bishop’s pawn, No. 14, “whiche is

lykened to taverners and vytayllers,” is thus described in Caxton’s own

words: “The sixte pawn whiche stondeth before the alphyn on the lyfte

syde is made in this forme . ffor hit is a man that hath the right hond

stretched out for to calle men, and holdeth in his left honde a loof of

breed and a cuppe of wyn . and on his gurdel hangyng a bondel of keyes,

and this resemblith the taverners hostelers and sellars of vytayl . and

194

these ought properly to be sette to fore the alphyn as to fore a juge,

for there sourdeth oft tymes amonge hem contencion noyse and stryf,

which behoveth to be determyned and trayted by the alphyn which is juge

of the kynge.”

The next book containing wood-cuts printed by Caxton is the “Mirrour

of the World, or thymage of the same,” as he entitles it at the head of

the table of contents. It is a thin folio consisting of one hundred

leaves; and, in the Prologue, Caxton informs the reader that it

“conteyneth in all lxvii chapitres and xxvii figures, without which it

may not lightly be understāde.” He also says that he translated it from

the French at the “request, desire, coste, and dispense of the

honourable and worshipful man Hugh Bryce, alderman cytezeyn of London,”

who intended to present the same to William, Lord Hastings, chamberlain

to Edward IV, and lieutenant of the same for the town of Calais and the

marches there. On the last page he again mentions Hugh Bryce and Lord

Hastings, and says of his translation: “Whiche book I begun first to

trāslate the second day of Janyuer the yere of our lord M.cccc.lxxx. And fynysshed the viii day of Marche

the same yere, and the xxi yere of the reign of the most crysten kynge,

Kynge Edward the fourthe.”IV.38

195

The “xxvii figures” mentioned by Caxton, without which the work might

not be easily understood, are chiefly diagrams explanatory of the

principles of astronomy and dialling; but besides those twenty-seven

cuts the book contains eleven more, which may be considered as

illustrative rather than explanatory. The following is a list of those

eleven cuts in the order in which they occur. They are less than the

cuts in the “Game of Chess;” the most of them not exceeding three inches

and a half by three.IV.39

1. A school-master or “doctor,” gowned, and seated on a high-backed

chair, teaching four youths who are on their knees. 2. A person

seated on a low-backed chair, holding in his hand a kind of globe;

astronomical instruments on a table before him. 3. Christ, or the

Godhead, holding in his hand a ball and cross. 4. The creation of

Eve, who appears coming out of Adam’s side.—The next cuts are

figurative of the “seven arts liberal.” 5. Grammar. A teacher

with a large birch-rod seated on a chair, his four pupils before him on

their knees. 6. Logic. Figure bare-headed seated on a chair, and

having before him a book on a kind of reading-stand, which he appears

expounding to his pupils who are kneeling. 7. Rhetoric. An upright

figure in a gown, to whom another, kneeling, presents a paper, from

which a seal is seen depending. 8. Arithmetic. A figure

seated, and having before him a tablet inscribed with numerical

characters. 9. Geometry. A figure standing, with a pair of

compasses in his hand, with which he seems to be drawing diagrams on a

table. 10. Music. A female figure with a sheet of music in her

hand, singing, and a man playing on the English flute.

11. Astronomy. Figure with a kind of quadrant in his hand, who

seems to be taking an observation.—An idea may be formed of the

manner in which those cuts are engraved from the fac-simile on the next

page of No. 10, “Music.”

There are wood-cuts in the Golden Legend, 1483; the Fables of Esop,

1484; Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, and other books printed by Caxton; but

it is unnecessary either to enumerate them or to give specimens, as they

are all executed in the same rude manner as the cuts in the Book of

Chess and the Mirror of the World. In the Book of Hunting and Hawking

printed at St. Albans, 1486, there are rude wood-cuts; as also in a

second and enlarged edition of the same book printed by Wynkyn de Worde,

Caxton’s successor, at Westminster in 1496. The most considerable

wood-cut printed in England previous to 1500 is, so far as regards the

design, a representation of the Crucifixion at the end of the

Golden Legend printed by Wynkyn de Worde in

196

1493.IV.40 In this cut, neither of the thieves on each side

of Christ appears to be nailed to the cross. The arms of the thief on

the right of Christ hang behind, and are bound to the transverse piece

of the cross, which passes underneath his shoulders. His feet are

neither bound nor nailed to the cross. The feet of the thief to the left

of Christ are tied to the upright piece of the cross, to which his hands

are also bound, his shoulders resting upon the top, and his face turned

upward towards the sky. To the left is seen the Virgin,—who has

fallen down,—supported by St. John. In the back-ground to the

right, the artist, like several others of that period, has represented

Christ bearing his cross.

Dr. Dibdin, at page 8 of the “Disquisition on the Early State of

Engraving and Ornamental Printing in Great Britain,” prefixed to Ames’s

and Herbert’s Typographical Antiquities, makes the following

observations on this cut: “The ‘Crucifixion’ at the end of the ‘Golden

Legend’ of 1493, which Wynkyn de Worde has so frequently subjoined to

his religious pieces, is, unquestionably, the effort of some ingenious

foreign artist. It is not very improbable that Rubens had a recollection

of one of the thieves, twisted, from convulsive agony, round the top of

the cross, when he executed his celebrated picture of the same

subject.”IV.41

197

In De Worde’s cut, however, it is to be remarked that the contorted

attitude of both the thieves results rather from the manner in which

they are bound to the cross, than from the convulsions of agony.

At page 7 of the same Disquisition it is said that the figures in the

Game of Chess, the Mirror of the World, and other works printed by

Caxton “are, in all probability, not the genuine productions of this

country; and may be traced to books of an earlier date printed abroad,

from which they were often borrowed without acknowledgment or the least

regard to the work in which they again appeared. Caxton, however, has

judiciously taken one of the prints from the ‘Biblia Pauperum’ to

introduce in his ‘Life of Christ.’ The cuts for his second edition of

‘Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales’ may perhaps safely be considered as the

genuine invention and execution of a British artist.”

Although I am well aware that the printers of the fifteenth century

were accustomed to copy without acknowledgment the cuts which appeared

in each other’s books, and though I think it likely that Caxton might

occasionally resort to the same practice, yet I am decidedly of opinion

that the cuts in the “Game of Chess” and the “Mirror of the World” were

designed and engraved in this country. Caxton’s Game of Chess is

certainly the first book of the kind which appeared with wood-cuts in

any country; and I am further of opinion that in no book printed

previous to 1481 will the presumed originals of the eleven principal

cuts in the Mirror of the World be found. Before we are required to

believe that the cuts in those two books were copied from similar

designs by some foreign artist, we ought to be informed in what work

such originals are to be found. If there be any merit in a first design,

however rude, it is but just to assign it to him who first employs the

unknown artist and makes his productions known. Caxton’s claims to the

merit of “illustrating” the Game of Chess and the Mirror of the World

with wood-cuts from original designs, I conceive to be

indisputable.

Dr. Dibdin, in a long note at pages 33, 34, and 35 of the

Typographical Antiquities, gives a confused account of the earliest

editions of books on chess. He mentions as the first, a Latin

edition—supposed by Santander to be the work of Jacobus de

Cessolis—in folio, printed about the year 1473, by Ketelaer and

Leempt. In this edition, however, there are no cuts, and the date is

only conjectural. He says that two editions of the work of Jacobus de

Cessolis on the Morality of Chess, in German and Italian, with

wood-cuts, were printed, without date, in the fifteenth century, and he

adds: “Whether Caxton borrowed the

198

cuts in his second edition from those in the 8vo. German edition without

date, or from this latter Italian one, I am not able to ascertain,

having seen neither.” He seems satisfied that Caxton had borrowed

the cuts in his book of chess, though he is at a loss to discover the

party who might have them to lend. Had he even seen the two

editions which he mentions, he could not have known whether Caxton had

borrowed his cuts from them or not until he had ascertained that they

were printed previously to the English edition. There is a German

edition of Jacobus de Cessolis, in folio, with wood-cuts supposed to be

printed in 1477, at Augsburg, by Gunther Zainer, but both date and

printer’s name are conjectural. The first German edition of this work

with wood-cuts, and having a positive date, I believe to be that

printed at Strasburg by Henry Knoblochzer in 1483. Until a work on chess

shall be produced of an earlier date than that ascribed to Caxton’s, and

containing similar wood-cuts, I shall continue to believe that the

wood-cuts in the second English edition of the “Game and Playe of the

Chesse” were both designed and executed by an English artist; and I

protest against bibliographers going a-begging with wood-cuts found in

old English books, and ascribing them to foreign artists, before they

have taken the slightest pains to ascertain whether such cuts were

executed in England or not.

The wood-cuts in the Game of Chess and the Mirror of the World are

equally as good as the wood-cuts which are to be found in books printed