lthough

wood engraving had fallen into almost utter neglect by the end of the

seventeenth century, and continued in a languishing state for many years

afterward, yet the art was never lost, as some persons have stated; for

both in England and in France a regular succession of wood engravers can

be traced from 1700 to the time of Thomas Bewick. The cuts which appear

in books printed in Germany, Holland, and Italy during the same period,

though of very inferior execution, sufficiently prove that the art

continued to be practised in those countries.

lthough

wood engraving had fallen into almost utter neglect by the end of the

seventeenth century, and continued in a languishing state for many years

afterward, yet the art was never lost, as some persons have stated; for

both in England and in France a regular succession of wood engravers can

be traced from 1700 to the time of Thomas Bewick. The cuts which appear

in books printed in Germany, Holland, and Italy during the same period,

though of very inferior execution, sufficiently prove that the art

continued to be practised in those countries.

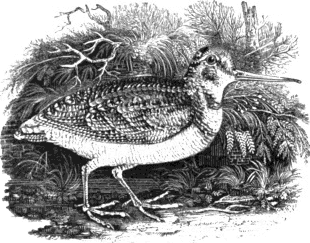

The first English book of this period which requires notice is an edition of Howel’s Medulla Historiæ Anglicanæ, octavo, printed at London in 1712.VII.1 There are upwards of sixty wood-cuts in this work, 447 and the manner in which they are executed sufficiently indicates that the engraver must have either been self-taught or the pupil of a master who did not understand the art. The blocks have, for the most part, been engraved in the manner of copper-plates; most of the lines, which a regular wood engraver would have left in relief, are cut in intaglio, and hence in the impression they appear white where they ought to be black. The bookseller, in an address to the reader, thus proceeds to show the advantages of those cuts, and to answer any objection that might be urged against them on account of their being engraved on wood. “The cuts added in this edition are intended more for use than show. The utility consists in these two particulars. 1. To make the better impression on the memory. 2. To show more readily when the notable passages in our history were transacted; which, without the knowledge of the names of the persons, are not to be found out, by even the best indexes. As for example: In what reign was it that a rebellious rout, headed by a vile fellow, made great ravage, and appearing in the King’s presence with insolence, their captain was stabbed upon the spot by the Lord-Mayor? Here, without knowing the names of some of the parties, which a world of people are ignorant of, the story is not to be found by an index; but by the help of the cut, which catches the eye, is soon discovered. We all have heard of the piety of one of our queens who sucked the poison out of her husband’s wound, but very few remember which of them it was, which the cut presently shows. The same is to be said of all the rest, since we have chosen only such things as are NOTABILIA in the history to describe in our sculptures.—And if it be objected that the graving is in wood, and not in copper, which would be more beautiful; we answer, that such would be much more expensive too. And we were willing to save the buyer’s purse; especially since even the best engraving would not better serve the purposes above-said.”

Though no mark is to be found on any of those cuts, I am inclined to think that they were executed by Edward Kirkall, whose name appears as the engraver of the copper-plate frontispiece to the book. The accounts which we have of Kirkall are extremely unsatisfactory. Strutt says that he was born at Sheffield in 1695; and that, visiting London in search of improvement, he was for some time employed in graving arms, stamps, and ornaments for books. It is, however, likely that he was born previous to 1695; for the frontispiece to Howel’s 448 Medulla is dated 1712, when, if Strutt be correct, Kirkall would be only seventeen. That he engraved on wood, as well as on copper, is unquestionable; and I am inclined to think that he either occasionally engraved small ornaments and head-pieces on type-metal for the use of printers, or that casts in this kind of metal were taken from some of his small cuts.VII.2

The head-pieces and ornaments in Maittaire’s Latin Classics, duodecimo, published by Tonson and Watts, 1713, were probably engraved on wood by Kirkall, as his initials, E. K., are to be found on one of the tail-pieces. Papillon speaks rather favourably of those small cuts, though he objects to the uniformity of the tint and the want of precision in the more delicate parts of the figures, such as the faces and hands. He notices the tail-piece with the mark E. K. as one of the best executed; and he suspects that these letters were intended for the name of an English painter—called Ekwits, to the best of his recollection,—who “taught the arts of painting and of engraving on wood to J. B. Jackson, so well known to the printers of Paris about 1730 from his having supplied them with so large a stock of indifferent cuts.”VII.3

The cuts in Croxall’s edition of Æsop’s Fables, first published by J. and R. Tonson and J. Watts, in 1722, were, in all probability, executed by the same person who engraved the head-pieces and other ornaments in Maittaire’s Latin Classics, printed for the same publishers about nine years before; and there is reason to believe that this person, as has been previously observed, was E. Kirkall. Bewick, in the introduction prefixed to his “Fables of Æsop and others,” first printed in 1818, says that the cuts in Croxall’s edition were “on metal, in the manner of wood.” He, however, gives no reason for this opinion, and I very much question its correctness. After a careful inspection I have not been able to discover any peculiar mark which should induce me to suppose that they had been engraved on metal; and without some such mark indicating that the engraved surface had been fastened to the block to raise it to the height of the type, I consider it impossible for any person to decide merely from the appearance of the impressions that those cuts were printed from a metallic surface. The difference, in point of impression, between a wood-cut and an engraving on type-metal in the same manner, or a cast in type-metal from a wood-cut, is not to be distinguished. A wood engraver of the present day, when casts 449 from wood-cuts are so frequently used instead of the original engraved block, decides that a certain impression has been from a cast, not in consequence of any peculiarity in its appearance denoting that it is printed from a metallic surface, but from certain marks—little flaws in the lines and minute “picks”—which he knows are characteristic of a “cast.” When a cast, however, has been well taken, and afterwards carefully cleared out with the graver, it is frequently impossible to decide that the impression has been taken from it, unless the examiner have also before him an impression from the original block with which it may be compared; and even then, a person not very well acquainted with the practice of wood engraving and the method of taking casts from engraved wood-blocks, will be extremely liable to decide erroneously.

Though it is by no means improbable that a person like Kirkall, who had been accustomed to engrave on copper, might attempt to engrave on type-metal in the same manner as on wood, and that he might thus execute a few small head-pieces and flowered ornaments, yet I consider it very unlikely that he should continue to prefer metal for the purpose of relief engraving after he had made a few experiments. The advantages of wood over type-metal are indeed so great, both as regards clearness of line and facility of execution, that it seems incredible that any person who had tried both materials should hesitate to give the preference to wood. If, however, the cuts in Croxall’s Æsop were really engraved on metal in the manner of wood, they are, as a series, the most extraordinary specimens of relief engraving for the purpose of printing, that have ever been executed. When Bewick stated that those cuts were engraved on metal, I am inclined to think that he founded his opinion rather on popular report than on close and impartial examination of the cuts themselves; and it is further to be observed that Thomas Bewick, with all his merits as a wood engraver, was not without his weaknesses as a man; he was not unwilling that people should believe that the art of wood engraving was lost in this country, and that the honour of its re-discovery, as well as of its subsequent advancement, was due to him. Though he was no doubt sincere in the opinion which he gave, yet those who know him are well aware that he would not have felt any pleasure in calling the attention of his readers to a series of wood-cuts executed in England upwards of thirty years before he was born, and which are not much inferior—except as regards the animals—to the cuts of fables engraved by himself and his brother previous to 1780.VII.4 The cuts in Croxall’s Æsop not only 450 display great improvement in the engraver, supposing him to be the same person that executed the head-pieces and ornaments in Maittaire’s Latin Classics printed in 1713, but are very much superior to any cuts contained in works of the same kind printed in France between 1700 and 1760.VII.5

Many of the subjects in Croxall are merely reversed copies of engravings on copper by S. Le Clerc, illustrative of a French edition 451 of Æsop’s Fables published about 1694. The first of the preceding cuts is a fac-simile of one of Le Clerc’s engravings; and the second is a copy of the same subject as it appears in Croxall. The fable to which they both relate is the Fox and the Goat.

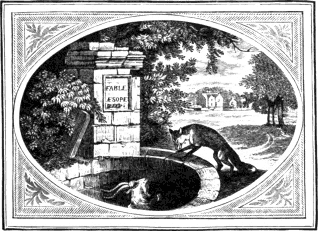

The above cut is by no means one of the best in Croxall: it has not been selected as a specimen of the manner in which those cuts are executed, but as an instance of the closeness with which the English wood-cuts have been copied from the French copper-plates. In several of the cuts in Bewick’s Fables of Æsop and others, the arrangement and composition appear to have been suggested by those in Croxall; but in every instance of this kind the modern artist has made the subject his own by the superior manner in which it is treated: he restores to the animals their proper forms, represents them acting their parts as described in the fable, and frequently introduces an incident or sketch of landscape which gives to the whole subject a natural character. The following copy of the Fox and Goat, in the Fables of Æsop and others, 1818-1823, will serve to show how little the modern artist has borrowed in such instances from the cuts in Croxall, and how much has been supplied by himself.

Between 1722 and 1724, Kirkall published by subscription twelve chiaro-scuros engraved by himself, chiefly after designs by old Italian masters. In those chiaro-scuros the outlines and the darker parts of the figures are printed from copper-plates, and the sepia-coloured tints afterwards impressed from wood-blocks; though they possess considerable merit, they are deficient in spirit, and will not bear a comparison with the chiaro-scuros executed by Ugo da Carpi and other early 452 Italian wood engravers. Most of them are too smooth, and want the bold outline and vigorous character which distinguish the old chiaro-scuros: what Kirkall gained in delicacy and precision by the introduction of mezzotint, he lost through the inefficient engraving of the wood-blocks. One of the largest of those chiaro-scuros is a copy of one of Ugo da Carpi’s—Æneas carrying his father on his shoulders—after a design by Raffaele. In Walpole’s Catalogue of Engravers, a notice of Kirkall’s “new method of printing, composed of etching, mezzotinto, and wooden stamps,” concludes with the following passage: “He performed several prints in this manner, and did great justice to the drawing and expression of the masters he imitated. This invention, for one may call it so, had much success, much applause, no imitators.—I suppose it is too laborious and too tedious. In an opulent country where there is great facility of getting money, it is seldom got by merit. Our artists are in too much hurry to gain it, or deserve it.”

About 1724 Kirkall published seventeen views of shipping, from designs by W. Vandevelde, which he also called “prints in chiaro-scuro.” They have, however, no just pretensions to the name as it is usually understood when applied to prints, for they are merely tinted engravings worked off in a greenish-blue ink. These so-called chiaro-scuros are decided failures.

Kirkall engraved, on copper, the plates in Rowe’s translation of Lucan’s Pharsalia, folio, published by Tonson, 1718; the plates for an edition of Inigo Jones’s Stonehenge, 1725; and a frontispiece to the works of Mrs. Eliza Haywood, which is thus alluded to in the Dunciad:

“See in the circle next Eliza placed,

Two babes of love close clinging to her waist;

Fair as before her works she stands confest,

In flowers and pearls by bounteous Kirkall drest.”

A considerable number of rude and tasteless ornaments and head-pieces, with the mark F. H., engraved on wood, are to be found in English books printed between 1720 and 1740. Several of them have been cast in type-metal,VII.6 as is evident from the marks of the pins, in the impressions, by which they have been fastened to the blocks; the same head-piece or ornament is also frequently found in books printed in the same year by different printers. Some of the best headings and tail-pieces of this period occur in a volume of “Miscellaneous Poems, original and translated, by several hands. Published 453 by Mr. Concanen,” London, printed for J. Peele, octavo, 1724. The subjects are, Apollo with a lyre; Minerva with a spear and shield; two men sifting corn; Hercules destroying the hydra; and a man with a large lantern. They are much superior to any cuts of the same kind with the mark F. H.; and from the manner in which they are executed, I am inclined to think that they are the work of the person who engraved the cuts in Croxall’s Æsop. The following is a fac-simile of one of the best of the cuts that I have ever seen with the mark F. H. It occurs as a tail-piece at the end of the preface to “Strephon’s Revenge: A Satire on the Oxford Toasts,” octavo, London, 1724.VII.7

John Baptist Jackson, an English wood engraver, was, according to Papillon, a pupil of the person who engraved the small head-pieces and ornaments in Maittaire’s Latin Classics, published by Tonson and Watts in 1713; and as the cuts in Croxall’s Æsop were probably engraved by the same person, as has been previously observed, it is not unlikely that Jackson, as his apprentice, might have some share in their execution. Though these cuts were much superior to any that had appeared in England for about a hundred years previously, wood engraving seems to have received but little encouragement. Probably from want of employment in his own country, Jackson proceeded to Paris, where he remained several years, chiefly employed in engraving head-pieces and ornaments for the booksellers. Papillon, who seems to have borne no good-will towards Jackson, thus speaks of him in the first volume of his “Traité de la Gravure en Bois.”

454“J. Jackson, an Englishman, who resided several years in Paris, might have perfected himself in wood engraving, which he had learnt of an English painter, as I have previously mentioned, if he had been willing to follow the advice which it was in my power to give him. Having called on me, as soon as he arrived in Paris, to ask for work, I for several months gave him a few things to execute in order to afford him the means of subsistence. He, however, repaid me with ingratitude; he made a duplicate of a flowered ornament of my drawing, which he offered, before delivering to me the block, to the person for whom it was to be engraved. From the reproaches that I received, on the matter being discovered, I naturally declined to employ him any longer. He then went the round of the printing-offices in Paris, and was obliged to engrave his cuts without order, and to offer them for almost nothing; and many of the printers, profiting by his distress, supplied themselves amply with his cuts. He had acquired a certain insipid taste which was not above the little mosaics on snuff-boxes; and with ornaments of this kind, after the manner of several other inferior engravers, he surcharged his works. His mosaics, however delicately engraved, are always deficient in effect, and display the engraver’s patience rather than his talent; for the other parts of the cut, consisting of delicate lines without tints or a gradation of light and shade, want that force which is necessary to render the whole striking. Such wood engravings, however deficient in this respect, are yet admired by printers of vulgar taste, who foolishly pretend that they most resemble copper-plates, and that they print better than cuts of a picturesque character, and containing a variety of tints.

“Jackson, being obliged, through destitution, to leave Paris, where he could get nothing more to do, travelled in France; and afterwards, being disgusted with his profession, he accompanied a painter to Rome, from whence he went to Venice, where, as I am informed, he married, and subsequently returned to England, his native country.”VII.8

Though Papillon speaks disparagingly of Jackson, the latter was at least as good an engraver as himself. Jackson appears to have visited Paris not later than 1726, for Papillon mentions a vignette and a large letter engraved by him in that year for a Latin and French dictionary, printed in 1727 by the brothers Barbou; and it is likely that he remained there till about 1731. In an Italian translation of the Lives of the Twelve Cæsars, printed there in quarto 1738, there is a large ornamental title-page of his engraving; and in the same year he engraved a chiaro-scuro of Christ taken down from the cross, from a 455 painting by Rembrandt,VII.9 in the possession of Joseph Smith, Esq. the British consul at Venice, a well-known collector of pictures and other works of art. Between 1738 and 1742, when residing at Venice, he also engraved twenty-seven large chiaro-scuros,—chiefly after pictures by Titian, G. Bassano, Tintoret, and P. Veronese,—which were published in a large folio volume in the latter year. They are very unequal in point of merit; some of them appearing harsh and crude, and others flat and spiritless, when compared with similar productions of the old Italian wood engravers. One of the best is the Martyrdom of St. Peter Dominicanus, after Titian, with the date 1739; the manner in which the foliage of the trees is represented is particularly good. On his return to England he seems to have totally abandoned the practice of wood engraving in the ordinary manner for the purpose of illustrating or ornamenting books; for I have not been able to discover any English wood-cut of the period that either contains his mark, or seems, from its comparative excellence, to have been of his engraving. Finding no demand in this country for wood-cuts, he appears to have tried to render his knowledge of engraving in chiaro-scuro available for the purpose of printing paper-hangings. In an “Essay on the Invention of Engraving and Printing in Chiaro Oscuro,”VII.10 published in his name in 1754, we learn that he was then engaged in a manufacture of this kind at Battersea. The account given in this essay of the origin and progress of chiaro-scuro engraving is frequently incorrect; and from several of the statements which it contains, it would seem that the writer was very imperfectly acquainted with the works of his predecessors and contemporaries in the same department of wood engraving. From the following passage, which is to be found in the fifth page, it is evident that the writer was either ignorant of what had been done in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and even in his own age, or that he was wishful to enhance the merit of Mr. Jackson’s process by concealing what had recently been done in the same manner by others. “After having said all this, it may seem highly improper to give to Mr. Jackson the merit of inventing this art; but let me be permitted to say, that an art recovered is less little than an art invented. The works of the former artists remain indeed; but the manner in which they were done is entirely lost: the inventing then the manner is really due to this latter undertaker, since no writings, or other remains, are to be found by 456 which the method of former artists can be discovered, or in what manner they executed their works; nor, in truth, has the Italian method since the beginning of the sixteenth century been attempted by any one except Mr. Jackson.” What is here called the “Italian method,” that is, the method of executing chiaro-scuros entirely on wood, was practised in France at the end of the seventeenth century: and Nicholas Le Sueur had engraved several cuts in this manner about 1730, the very time when Jackson was living in Paris. The principles of the art had also been applied in France to the execution of paper-hangings upwards of fifty years before Jackson attempted to establish the same kind of manufacture in England. Not a word is said of the chiaro-scuros of Kirkall,VII.11 from whom it is likely that Jackson first acquired his knowledge of chiaro-scuro engraving: with the exception of the outlines and some other parts in these chiaro-scuros being executed in mezzotint, the printing of the rest from wood-blocks is precisely the same as in the Italian method.

The Essay contains eight prints illustrative of Mr. Jackson’s method; four are chiaro-scuros, and four are printed in “proper colours,” as is expressed in the title, in imitation of drawings. They are very poorly executed, and are very much inferior to the chiaro-scuros engraved by Jackson when residing at Venice. The prints in “proper colours” are egregious failures. The following notices respecting Mr. Jackson are extracted from the Essay in question.

“Certainly Mr. Jackson, the person of whom we speak, has not spent less time and pains, applied less assiduity, or travelled to fewer distant countries in search of perfecting his art, than other men; having passed twenty years in France and Italy to complete himself in drawing after the best masters in the best schools, and to see what antiquity had most worthy the attention of a student in his particular pursuits. After all this time spent in perfecting himself in his discoveries, like a true lover of his native country, he is returned with a design to communicate all the means which his endeavours can contribute to enrich the land where he drew his first breath, by adding to its commerce, and employing its inhabitants; and yet, like a citizen of it, he would willingly enjoy some little share of those advantages before he leaves this world, which he must leave behind him to his countrymen when he shall be no more.”

“During his residence at Venice, where he made himself perfect 457 in the art which he professes, he finished many works well known to the nobility and gentry who travelled to that city whilst he lived in it.—Mr. Frederick, Mr. Lethuillier, and Mr. Smith, the English consul at Venice, encouraged Mr. Jackson to undertake to engrave in chiaro-oscuro, blocks after the most capital pictures of Titian, Tintoret, Giacomo Bassano, and Paul Veronese, which are to be found in Venice, and to this end procured him a subscription. In this work may be seen what engraving on wood will effectuate, and how truly the spirit and genius of every one of those celebrated masters are preserved in the prints.

“During his executing this work he was honoured with the encouragement of the Right Honourable the Marquis of Hartington, Sir Roger Newdigate, Sir Bouchier Wrey, and other English gentlemen on their travels at Venice, who saw Mr. Jackson drawing on the blocks for the print after the famous picture of the Crucifixion painted by Tintoret in the albergo of St. Roche. Those prints may now be seen at his house at Battersea.—Not content with having brought his works in chiaro-oscuro to such perfection, he attempted to print landscapes in all their original colours; not only to give to the world all the outline light and shade, which is to be found in the paintings of the best masters, but in a great degree their very manner and taste of colouring. With this intent he published six landscapes,VII.12 which are his first attempt in this nature, in imitation of painting in aquarillo or water-colours; which work was taken notice of by the Earl of Holderness, then ambassador extraordinary to the republic of Venice; and his excellency was pleased to permit the dedication of those prints to him, and to encourage this new attempt of printing pictures with a very particular and very favourable regard, and to express his approbation of the merit of the inventor.”

John Michael Papillon, one of the best French wood engravers of his age, was born in 1698. His grandfather and his father, as has been previously observed, were both wood engravers. In 1706, when only eight years old, he secretly made his first essay in wood engraving; and when only nine, his father, who had become aware of his amusing himself in this manner, gave him a large block to engrave, which he appears to have executed to his father’s satisfaction, though he had previously received no instructions in the art.VII.13 The block was intended 458 for printing paper-hangings, the manufacture of which was his father’s principal business. Though until the time of his father’s death, which happened in 1723, Papillon appears to have been chiefly employed in such works, and in hanging the papers which he had previously engraved, he yet executed several vignettes and ornaments for the booksellers, and sedulously endeavoured to improve himself in this higher department of his business.

Shortly after the death of his father he married; and, having given up the business of engraving paper-hangings, he laboured so hard to perfect himself in the art of designing and engraving vignettes and ornaments for books, that his head became affected; and he sometimes displayed such absence of mind that his wife became alarmed, fancying that “he no longer loved her.” On his assuring her that his behaviour was the result of his anxiety to improve himself in drawing and engraving on wood, and to write something about the art, she encouraged him in his purpose, and aided him with her advice, for, as she was the daughter of a clever man, M. Chaveau, a sculptor, and had herself made many pretty drawings on fans, she had some knowledge of design. Papillon’s fits of absence, however, though they may have been proximately induced by close application and anxiety about his success in the line to which he intended to apply himself in future, appear to have originated in a tendency to insanity, which at a later period displayed itself in a more decided manner. In 1759, in consequence of a determination of blood to the head, as he says, through excessive joy at seeing his only daughter, who had lived from the age of four years with her uncle, combined with a recollection of his former sorrows, his mind became so much disordered that it was necessary to send him to an hospital, where, through repeated bleedings and other remedies, he seems to have speedily recovered. He mentions that in the same year, four other engravers were attacked by the same malady, and that only one of them regained his senses.VII.14

Papillon’s endeavours to improve himself were not unsuccessful; the cuts which he engraved about 1724, though mostly small, possess 459 considerable merit; they are not only designed with much more feeling than the generality of those executed by other French engravers of the period, but are also much more effective, displaying a variety of tint and a contrast of light and shade which are not to be found in the works of his contemporaries. In 1726, in order to divert his anxiety and to bring his cuts into notice, he projected Le petit Almanach de Paris, which subsequently was generally known as “Le Papillon.” The first that he published was for the year 1727; and the wood-cuts which it contained equally attracted the attention of the public and of connoisseurs. Monsieur Colombat, the editor of the Court Calendar, spoke highly of the cut for the mouth of January; the cross-hatchings, he said, were executed in the first style of wood engraving, and he kindly predicted to Papillon that he would one day excel in his art. From this time he seems to have no longer had any doubt of his own abilities, but, on the contrary, to have entertained a very high opinion of them. He appears to have considered wood engraving as the highest of all the graphic arts, and himself as the greatest of all its professors, either ancient or modern.

From this, to him, memorable epoch,—the publication of “Le petit Almanach de Paris,” with cuts by Papillon,—he appears to have been seldom without employment, for in the Supplement to the “Traité de la Gravure en Bois,” he mentions that in 1768, the “Collection of the Works of the Papillons,” presented by him to the Royal Library, contained upwards of five thousand pieces of his own engraving. This “Recueil des Papillons,” which he seems to have considered as a family monument “ære perennius,” is perpetually referred to in the course of his work. It consisted of four large folio volumes containing specimens of wood engravings executed by the different members of the Papillon family for three generations—his grandfather, his father, his uncle, his brother, and himself.

Papillon was employed not only by the booksellers of his own country, but also by those of Holland. A book, entitled “Historische School en Huis-Bybel,” printed at Amsterdam in 1743, contains two hundred and seventeen cuts, all of which appear to have been either engraved by Papillon himself, or under his superintendence. His name appears on several of them, and they are all engraved in the same style. From a passage in the dedication, it seems likely that they had appeared in a similar work printed at the same place a few years previously. They are generally executed in a coarser manner than those contained in Papillon’s own work, but the style of engraving and general effect are the same. The cut on the next page is a copy of the first, which is one of the best in the work. To the left is 460 Papillon’s name, engraved, as was customary with him, in very small letters, with the date, 1734.

Papillon’s History of Wood Engraving, published in 1766, in two octavo volumes, with a Supplement,VII.15 under the title of “Traité Historique et Pratique de la Gravure en Bois,” is said to have been projected, and partly written, upwards of thirty years before it was given to the public. Shortly after his being admitted a member of the Society of Arts, in 1733, he read, at one of the meetings, a paper on the history and practice of wood engraving; and in 1735 the Society signified their approbation that a work written by him on the subject should be printed. It appears that the first volume of such a work was actually printed between 1736 and 1738, but never published. He does not explain why the work was not proceeded with at that time; and it would be useless to speculate on the possible causes of the interruption. He mentions that a copy of this volume was preserved in the Royal Library; and he charges Fournier the younger, who between 1758 and 1761 published three tracts on the invention of wood engraving and printing, with having availed himself of a portion of the historical information contained in this volume. The public, however, according to his own statement, gained by the delay; as he grew older he gained more knowledge of the history of the art, and “invented” several important improvements in his practice, all of which are embodied in his later work. In 1758 he also discovered the memoranda which he had made at Monsieur De Greder’s, in 1719 or 1720, relative to the interesting twins, 461 Alexander Alberic Cunio and his sister Isabella, who, about 1284, between the fourteenth and sixteenth years of their age, executed a series of wood engravings illustrative of the history of Alexander the Great.VII.16 However the reader may be delighted or amused by the romantic narrative of the Cunio, Papillon’s reputation as the historian of his art would most likely have stood a little higher had he never discovered those memoranda. They have very much the character of ill-contrived forgeries; and even supposing that he believed them, and printed them in good faith, his judgment must be sacrificed to save his honesty.

The first volume of Papillon’s work contains the history of the art; it is divided into two parts, the first treating of wood engraving for the purpose of printing in the usual manner from a single block, and the second treating of chiaro-scuro. He does not trace the progress of the art by pointing out the improvements introduced at different periods; he enumerates all the principal cuts that he had seen, without reference to their execution as compared with those of an earlier date; and, from his desire to enhance the importance of his art, he claims almost every eminent painter whose name or mark is to be found on a cut, as a wood engraver. He is in this respect so extremely credulous as to assert that Mary de Medici, Queen of Henry IV. of France, had occasionally amused herself with engraving on wood; and in order to place the fact beyond doubt he refers to a cut representing the bust of a female, with the following inscription: “Maria Medici. F. m.d.lxxxvii.” “The engraving,” he observes, with his usual bonhomie, “is rather better than what might be reasonably expected from a person of such quality; it contains many cross-hatchings, somewhat unequal indeed, and occasionally imperfect, but, notwithstanding, sufficiently well engraved to show that she had executed several wood-cuts before she had attempted this. I know more than one wood engraver—or at least calling himself such—who is incapable of doing the like.” In 1587, the date of this cut, Mary de Medici was only fourteen years old; and since its execution, according to Papillon, shows that she was then no novice in the art, she must have acquired her practical knowledge of wood engraving at rather an early age,—at least for a princess. Papillon never seems to have considered that F is the first letter of “Filia” as well as of “Fecit,” nor to have suspected that the cut was simply a portrait of Mary de Medici, and not a specimen of her engraving.

From the following passage in the preface, he seems to have been 462 aware that his including the names of many eminent painters in his list of wood engravers would be objected to. “Some persons, who entertain a preconceived opinion that many painters whom I mention have not engraved on wood, may perhaps dispute the works which I ascribe to them. Of such persons I have to request that they will not condemn me before they have acquainted themselves with my researches and examined my proofs, and that they will judge of them without prejudice or partiality.” The “researches” to which he alludes, appear to have consisted in searching out the names and marks of eminent painters in old wood-cuts, and his “proofs” are of the same kind as that which he alleges in support of his assertion that Mary de Medici had engraved on wood,—a fact which, as he remarks, “was unknown to Rubens.” The historical portion of Papillon’s work is indeed little more than a confused catalogue of all the wood-cuts which had come under his observation; it abounds in errors, and almost every page affords an instance of his credulity.

In the second volume, which is occupied with details relative to the practice of the art, Papillon gives his instructions and enumerates his “inventions” in a style of complacent self-conceit. The most trifling remarks are accompanied by a reference to the “Recueil des Papillons;” and the most obvious means of effecting certain objects,—such means as had been regularly adopted by wood engravers for upwards of two hundred years previously, and such as in succeeding times have suggested themselves to persons who never received any instructions in the art,—are spoken of as important discoveries, and credit taken for them accordingly. One of his fancied discoveries is that of lowering the surface of a block towards the edges in order that the engraved lines in those parts may be less subject to the action of the plattin in printing, and consequently lighter in the impression. The Lyons Dance of Death, 1538, affords several instances of blocks lowered in this manner, not only towards the edges, but also in the middle of the cut, whenever it was necessary that certain delicately engraved lines should be lightly printed, and thus have the appearance of gradually diminishing till their extremities should scarcely be distinguishable from the paper on which they are impressed. Numerous instances of this practice are frequent in wood-cuts executed from 1540 to the decline of the art in the seventeenth century. Lowering was also practised by the engraver of the cuts in Croxall’s Æsop; by Thomas Bewick, who acquired a knowledge of wood engraving without a master; and by the self-taught artist who executed the cuts in Alexander’s Expedition down the Hydaspes, a poem by Dr. Thomas Beddoes, printed in 1792, but never published.VII.17 As the 463 same practice has recently been claimed as an “invention,” it would seem that some wood engravers are either apt to ascribe much importance to little things, or are singularly ignorant of what has been done by their predecessors. Such an “invention,” though unquestionably useful, surely does not require any particular ingenuity for its discovery; such “discoveries” every man makes for himself as soon as he feels the want of that which the so-called invention will supply. The man who pares the cork of a quart bottle in order to make it fit a smaller one is, with equal justice, entitled to the name of an inventor, provided he was not aware of the thing having been done before: such an “adaptation of means to the end” cannot, however, be considered as an effort of genius deserving of public commendation.

In Papillon’s time it was not customary with French engravers on wood to have the subject perfectly drawn on the block, with all the lines and hatchings pencilled in, and the effect and the different tints indicated either in pencil or in Indian ink, as is the usual practice in the present day. The design was first drawn on paper; from this, by means of tracing paper, the engraver made an outline copy on the block; and, without pencilling in all the lines or washing in the tints, he proceeded to “translate” the original, to which he constantly referred in the progress of his work, in the same manner as a copper-plate engraver does to the drawing or painting before him. Papillon perceived the disadvantages which resulted from this mode of proceeding; and though he still continued to make his first drawing on paper, he copied it more carefully and distinctly on the block than was usual with his contemporaries. He was thus enabled to proceed with greater certainty in his engraving; what he had to effect was immediately before him, and it was no longer necessary to refer so frequently to the original. To the circumstance of the drawings being perfectly made on the block, Papillon ascribes in a great measure the excellence of the old wood engravings of the time of Durer and Holbein.

Papillon, although always inclined to magnify little things connected with wood engraving, and to take great credit to himself for trifling “inventions,” was yet thoroughly acquainted with the practice of his art. The mode of thickening the lines in certain parts of a cut, after it has 464 been engraved, by scraping them down, was frequently practised by him, and he explains the manner of proceeding, and gives a cut of the tools required in the operation.VII.18 As Papillon, previous to the publication of his book, had contributed several papers on the subject of wood engraving to the famed Encyclopédie, he avails himself of the second volume of the Traité to propose several additions and corrections to those articles. The following definition proposed to be inserted in the Encyclopédie, after the article Gratuit, will afford some idea of the manner in which he is accustomed to speak of his “inventions.” The term which he explains is “Gratture ou Grattage,” literally, “Scraping,” the practice just alluded to. “This is, according to the new manner of engraving on wood, the operation of skilfully and carefully scraping down parts in an engraved block which are not sufficiently dark, in order to give them, as may be required, greater strength, and to render the shades more effective. This admirable plan, utterly unknown before, was accidentally discovered in 1731 by M. Papillon, by whom the art of wood engraving is advanced to a state tending to perfection, and approaching more and more towards the beauty of engraving on copper.” The tools used by Papillon to scrape down the lines of an engraved block, and thus render them thicker and, consequently, the impression darker, differ considerably in shape from those used for the same purpose by modern wood engravers in England. This tool now principally used is something like a copper-plate engraver’s burnisher, and occasionally a fine and sharp file is employed.

In Papillon’s time the French wood engravers appear to have held the graver in the manner of a pen, and in forming a line to have cut towards them as in forming a down-stroke in writing, and to have engraved on the longitudinal, and not the cross section of the wood. Modern English wood engravers, having the rounded handle of the graver supported against the hollow of the hand, and directing the blade by means of the fore-finger and thumb, cut the line from them; and always engrave on the cross section of the wood. Papillon mentions box, pear-tree, apple-tree, and the wood of the service-tree, as the best for the purposes of engraving: box was generally used for the smaller and finer cuts intended for the illustration or ornament of books; the larger cuts, in which delicacy was not required, were mostly engraved on pear-tree wood. Apple-tree wood was principally used by the wood engravers of Normandy. Next to box, Papillon prefers the wood of the service-tree. The box brought from Turkey, though of larger size, he considers inferior to that of Provence, Italy, or Spain.

465Although Papillon’s modus operandi differs considerably from that of English wood engravers of the present day, I am not aware of any supposed discovery in the modern practice of the art that was not known to him. The methods of lowering a block in certain parts before drawing the subject on it, and of thickening the lines, and thus getting more colour, by scraping the surface of the cut when engraved, were, as has been observed, known to him; he occasionally introduced cross-hatchings in his cuts;VII.19 and in one of his chapters he gives instructions how to insert a plug in a block, in order to replace a part which had either been spoiled in the course of engraving or subsequently damaged. One of the improvements which he suggested, but did not put in practice, was a plan for engraving the same subject on two, three, or four blocks, in order to obtain cross-hatchings and a variety of tints with less trouble than if the subject were entirely engraved on the same block. Such cuts were not to be printed as chiaro-scuros, but in the usual manner, with printer’s ink. It is worthy of observation that Bewick in the latter part of his life had formed a similar opinion of the advantages of engraving a subject on two or more blocks, and thus obtaining with comparative ease such cross-lines and varied tints as could only be executed with great difficulty on a single block. He, however, proceeded further than Papillon, for he began to engrave a large cut which he intended to finish in this manner; and he was so satisfied that the experiment would be successful, that when the pressman handed to him a proof of the first block, he exclaimed, “I wish I was but twenty years younger!”

Papillon, in his account of the practice of the art, explains the manner of engraving and printing chiaro-scuros; and in illustration of the process he gives a cut executed in this style, together with separate impressions from each of the four blocks from which it is printed. There is also another cut of the same kind prefixed to the second part of the first volume, containing the history of engraving in chiaro-scuro. Scarcely anything connected with the practice of wood engraving appears to have escaped his notice. He mentions the effect of the breath in cold weather as rendering the block damp and the drawing less distinct; and he gives in one of his cuts the figure of a “mentonnière,”—that is to say, a piece of quilted linen, like the pad used by women to keep their bonnets cocked up,—which, being placed 466 before the mouth and nostrils, and kept in its place by strings tied behind the head, screened the block from the direct action of the engraver’s breath.

He frequently complains of the careless manner in which wood-cuts were printed;VII.20 but from the following passage we learn that the inferiority of the printed cuts when compared with the engraver’s proofs did not always proceed from the negligence of the printer. “Some wood engravers have the art of fabricating proofs of their cuts much more excellent and delicate than they fairly ought to be; and the following is the manner in which they contrive to obtain tolerably decent proofs from very indifferent engravings. They first take two or three impressions, and then, to obtain one to their liking, and with which they may deceive their employers, they only ink the block on those places which ought to be dark, leaving the distances and lighter parts without any ink, except what remained after taking the previous impressions. The proof which they now obtain appears extremely delicate in those parts which were not properly inked; but when they come to be printed in a page with type, the impression is quite different from the proof which the engraver delivers with the blocks; there is no variety of tint, all is hard, and the distance is sometimes darker than objects in the fore-ground. I run no great risk in saying that all the three Le Sueurs have been accustomed to practise this deception.”VII.21

All the cuts in Papillon’s work, except the portrait prefixed to the first volume,VII.22 are his own engraving, and, for the most part, from his own designs. The most of the blocks were lent to the author by the different persons for whom he had engraved them long previous to the appearance of his work.VII.23 They are introduced as ornaments at the beginning and end of the chapters; but though they may enable the reader to judge of Papillon’s abilities as a designer and engraver on wood, beyond this they do not in the least illustrate the progress of the art. 467 The execution of some of the best is extremely neat; and almost all of them display an effect—a contrast of black and white—which is not to be found in any other wood-cuts of the period. A few of the designs possess considerable merit, but in by far the greater number simplicity and truth are sacrificed to ornament and French taste. Whatever may be Papillon’s faults as a historian of the art, he deserves great credit for the diligence with which he pursued it under unfavourable circumstances, and for his endeavours to bring it into notice at a time when it was greatly neglected. His labours in this respect were, however, attended with no immediate fruit. He died in 1776, and his immediate successors do not appear to have profited by his instructions. The wood-cuts executed in France between 1776 and 1815 are generally much inferior to those of Papillon; and the recent progress which wood engraving has made in that country seems rather to have been influenced by English example than by his precepts.

Nicholas Le Sueur—born 1691, died 1764,—was, next to Papillon, the best French wood engraver of his time. His chiaro-scuros, printed entirely from wood-blocks, are executed with great boldness and spirit, and partake more of the character of the earlier Italian chiaro-scuros than any other works of the same kind engraved by his contemporaries.VII.24 He chiefly excelled in the execution of chiaro-scuros and large cuts; his small cuts are of very ordinary character; they are generally engraved in a hard and meagre style, want variety of tint, and are deficient in effect.

P. S. Fournier, the younger, a letter-founder of considerable reputation,—born at Paris 1712, died 1768,—occasionally engraved on wood. Papillon says that he was self-taught; and that he certainly would have made greater progress in the art had he not devoted himself almost exclusively to the business of type-founding. Monsieur Fournier is, however, better known as a writer on the history of the art than as a practical wood engraver. Between 1758 and 1761 he published three tracts relating to the origin and progress of wood engraving, and the invention of typography.VII.25 From these works it is evident that, though 468 he takes no small credit to himself for his practical knowledge of wood engraving and printing, he was very imperfectly acquainted with his subject. They abound in errors which it is impossible that any person possessing the knowledge he boasts of should commit, unless he had very superficially examined the books and cuts on which he pronounces an opinion. He seems indeed to have thought that, from the circumstance of his being a wood engraver and letter-founder, his decisions on all doubtful matters in the early history of wood engraving and printing should be received with implicit faith. Looking at the comparatively small size of his works, no writer, not even Papillon himself, has committed so many mistakes; and his decisions are generally most peremptory when utterly groundless or evidently wrong. He asserts that Faust and Scheffer’s Psalter, 1457-1459, is printed from moveable types of wood, and that the most of the earliest specimens of typography are printed from the same kind of types; and in the fulness of his knowledge he also declares that the text of the Theurdank is printed not from types, but from engraved wood-blocks. Like Papillon, he seems to have possessed a marvellous sagacity in ferreting out old wood engravers. He says that Andrea Mantegna engraved on wood a grand triumph in 1486; that Sebastian Brandt engraved in 1490 the wood-cuts in the Ship of Fools,VII.26 after the designs of J. Locher; and that Parmegiano 469 executed several wood-cuts after designs by Raffaele. He decides positively that Albert Durer, Lucas Cranach, Titian, and Holbein were wood engravers, and, like Papillon, he includes Mary de Medici in the list. Papillon appears to have had good reason to complain that Fournier had availed himself of his volume printed in 1738. His taste appears to have been scarcely superior to his knowledge and judgment: he mentions a large and coarsely engraved cut of the head of Christ as one of the best specimens of Albert Durer’s engraving; and he says that Papillon’s cuts are for excellence of design and execution equal to those of the greatest masters!

From a passage in one of Fournier’s tracts—Remarques Typographiques, 1761,—it is evident that wood engraving was then greatly neglected in Germany. It relates to the following observation of M. Bär’s, almoner of the Swedish chapel at Paris, on the length of time necessary to engrave a number of wooden types sufficient to print such a work as Faust and Scheffer’s Psalter: “M. Schœpflin declares that, by the general admission of all experienced persons, it would require upwards of six years to complete such a work in so perfect a manner.” The following is Fournier’s rejoinder: “To understand the value of this remark, it ought to be known that, so far from there being many experienced wood engravers to choose from, M. Schœpflin would most likely experience some difficulty in finding one to consult.” The wood-cuts which occur in German books printed between 1700 and 1760 are certainly of the most wretched kind; contemptible alike in design and execution. Some of the best which I have seen—and they are very bad—are to be found in a thin folio entitled “Orbis Literatus Germanico-Europaeus,” printed at Frankfort in 1737. They are cuts of the seals of all the principal colleges and academical foundations in Germany. The art in Italy about the same period was almost equally neglected. An Italian wood engraver, named Lucchesini, executed several cuts between 1760 and 1770. Most of the head-pieces and ornaments in the Popes’ Decretals, printed at Rome at this period, were engraved by him; and he also engraved the cuts in a Spanish book entitled “Letania Lauretana de la Virgen Santissima,” printed at Valencia in 1768. It is scarcely necessary to say that these cuts are of the humblest character.

Though wood engraving did not make any progress in England from 1722 to the time of Thomas Bewick, yet the art was certainly never lost in this country; the old stock still continued to put forth a branch—non deficit alter—although not a golden one. Two wood-cuts tolerably well executed, and which show that the engraver was acquainted with the practice of “lowering,” occur in a thin quarto, London, printed for H. Payne, 1760. The book and the cuts are thus noticed in Southey’s Life 470 of Cowper, volume I. page 50. The writer is speaking of the Nonsense Club, of which Cowper was a member.

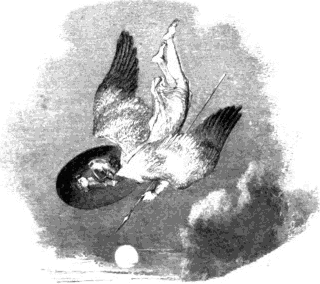

“At those meetings of

Jest and youthful Jollity,

Sport that wrinkled Care derides,

And Laughter holding both his sides,

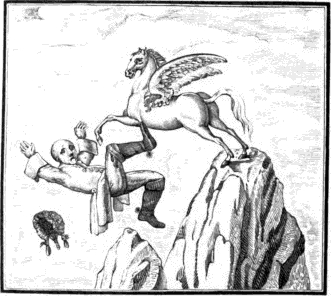

there can be little doubt that the two odes to Obscurity and Oblivion originated, joint compositions of Lloyd and Colman, in ridicule of Gray and Mason. They were published in a quarto pamphlet, with a vignette, in the title-page, of an ancient poet safely seated and playing on his harp; and at the end a tail-piece representing a modern poet in huge boots, flung from a mountain by his Pegasus into the sea, and losing his tie-wig in the fall.” The following is a fac-simile of the cut representing the poet’s fall. He seems to have been tolerably confident of himself, for, though the winged steed has no bridle, he is provided with a pair of formidable spurs.

The cuts in a collection of humorous pieces in verse, entitled “The Oxford Sausage,” 1764, are evidently by the same engraver, and almost every one of them affords an instance of “lowering.” At the foot of one of them, at page 89, the name “Lister” is seen; the subject is a bacchanalian figure mounted on a winged horse, which has undoubtedly been drawn from the same model as the Pegasus in Colman and Lloyd’s burlesque odes. In an edition of the 471 Sausage, printed in 1772, the name of “T. Lister” occurs on the title-page as one of the publishers, and as residing at Oxford. Although those cuts are generally deficient in effect, their execution is scarcely inferior to many of those in the work of Papillon; the portrait indeed of “Mrs. Dorothy Spreadbury, Inventress of the Oxford Sausage,” forming the frontispiece to the edition of 1772, is better executed than Monsieur Nicholas Caron’s votive portrait of Papillon, “the restorer of the art of wood engraving.”

In 1763, a person named S. Watts engraved two or three large wood-cuts in outline, slightly shaded, after drawings by Luca Cambiaso. Impressions of those cuts are most frequently printed in a yellowish kind of ink. About the same time Watts also engraved, in a bold and free style, several small circular portraits of painters. In Sir John Hawkins’s History of Music, published in 1776, there are four wood-cuts; and at the bottom of the largest—Palestrini presenting his work on Music to the Pope—is the name of the engraver thus: T. Hodgson. Sculp. Dr. Dibdin, in noticing this cut, in his Preliminary Disquisition on Early Engraving and Ornamental Printing, prefixed to his edition of the Typographical Antiquities, says that it was “done by Hodgson, the master of the celebrated Bewick.”VII.27 If by this it is meant that Bewick was the apprentice of Hodgson, or that he obtained from Hodgson his knowledge of wood engraving, the assertion is incorrect. It is, however, almost certain that Bewick, when in London in 1776, was employed by Hodgson, as will be shown in its proper place.

Having now given some account of wood engraving in its languishing state—occasionally showing symptoms of returning vigour, and then almost immediately sinking into its former state of depression—we at length arrive at an epoch from which its revival and progressive improvement may be safely dated. The person whose productions recalled public attention to the neglected art of wood engraving was

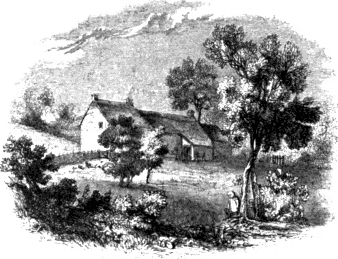

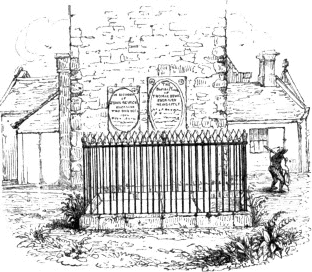

472This distinguished wood engraver, whose works will be admired as long as truth and nature shall continue to charm, was born on the 10th or 11th of August, 1753, at Cherry-burn, in the county of Northumberland, but on the south side of the Tyne, about twelve miles westward of Newcastle.

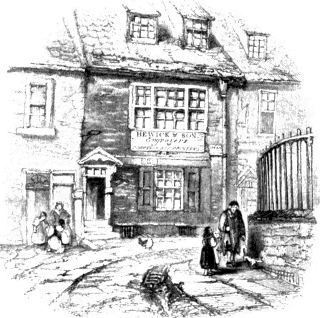

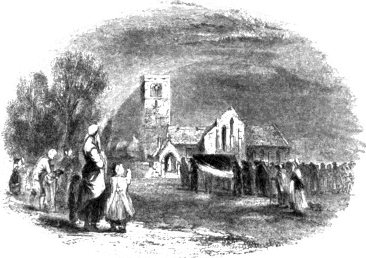

THE HOUSE IN WHICH BEWICK WAS BORN.

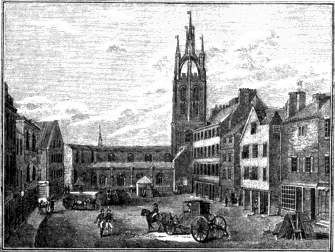

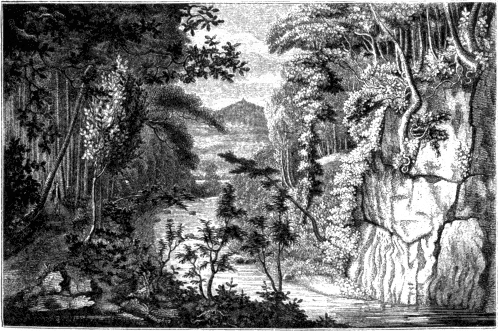

His father rented a small land-sale colliery at Mickley-bank, in the neighbourhood of his dwelling, and it is said that when a boy the future wood engraver sometimes worked in the pit. At a proper age he was sent as a day-scholar to a school kept by the Rev. Christopher Gregson at Ovingham, on the opposite side of the Tyne. The Parsonage House, in which Mr. Gregson lived, is pleasantly situated on the edge of a sloping bank immediately above the river; and many reminiscences of the place are to be found in Bewick’s cuts; the gate at the entrance is introduced, with trifling variations, in three or four different subjects; and a person acquainted with the neighbourhood will easily recognise in his tail-pieces several other little local sketches of a similar kind. In the time of the Rev. James Birkett, Mr. Gregson’s successor, Ovingham school had the character of being one of the best private schools in the county; and several gentlemen, whose talents reflect credit on their teacher, received their education there. In the following cut, representing a view of Ovingham from the south-westward, the Parsonage House, with its garden sloping down to the Tyne, is perceived immediately to the right of the clump of large trees. The bank on which those trees grow is known as the 473 crow-tree bank. The following lines, descriptive of a view from the Parsonage House, are from “The School Boy,” a poem, by Thomas Maude, A.M., who received his early education at Ovingham under Mr. Birkett.

PARSONAGE AT OVINGHAM.

“But can I sing thy simpler pleasures flown,

Loved Ovingham! and leave the chief unknown,—

Thy annual Fair, of every joy the mart,

That drained my pocket, ay, and took my childish heart?

Blest morn! how lightly from my bed I sprung,

When in the blushing east thy beams were young;

While every blithe co-tenant of the room

Rose at a call, with cheeks of liveliest bloom.

Then from each well-packed drawer our vests we drew,

Each gay-frilled shirt, and jacket smartly new.

Brief toilet ours! yet, on a morn like this,

Five extra minutes were not deemed amiss.

Fling back the casement!—Sun, propitious shine!

How sweet your beams gild the clear-flowing Tyne,

That winds beneath our master’s garden-brae,

With broad bright mazes o’er its pebbly way.

See Prudhoe! lovely in the morning beam:—

Mark, mark, the ferry-boat, with twinkling gleam,

Wafting fair-going folks across the stream.

Look out! a bed of sweetness breathes below,

Where many a rocket points its spire of snow;

And from the Crow-tree Bank the cawing sound

Of sable troops incessant poured around!

Well may each little bosom throb with joy!

On such a morn, who would not be a boy?”

Bewick’s school acquirements probably did not extend beyond English reading, writing, and arithmetic; for, though he knew a little 474 Latin, he does not appear to have ever received any instructions in that language. In a letter dated 18th April, 1803, addressed to Mr. Christopher Gregson,VII.28 London, a son of his old master, introducing an artist of the name of Murphy, who had painted his portrait, Bewick humorously alludes to his beauty when a boy, and to the state of his coat-sleeve, in consequence of his using it instead of a pocket-handkerchief. Bewick, it is to be observed, was very hard-featured, and much marked with the small-pox. After mentioning Mr. Murphy as “a man of worth, and a first-rate artist in the miniature line,” he thus proceeds: “I do not imagine, at your time of life, my dear friend, that you will be solicitous about forming new acquaintances; but it may not, perhaps, be putting you much out of the way to show any little civilities to Mr. Murphy during his stay in London. He has, on his own account, taken my portrait, and I dare say will be desirous to show you it the first opportunity: when you see it, you will no doubt conclude that T. B. is turning bonnyer and bonnyerVII.29 in his old days; but indeed you cannot help knowing this, and also that there were great indications of its turning out so long since. But if you have forgot our earliest youth, perhaps your brother P.VII.30 may help you to remember what a great beauty I was at that time, when the grey coat-sleeve was glazed from the cuff towards the elbows.” The words printed in Italics are those that are underlined by Bewick himself.

Bewick, having shown a taste for drawing, was placed by his father as an apprentice with Mr. Ralph Beilby, an engraver, living in Newcastle, to whom on the 1st of October 1767 he was bound for a term of seven years. Mr. Beilby was not a wood engraver; and his business in the copper-plate line was of a kind which did not allow of much scope for the display of artistic talent. He engraved copper-plates for books, when any by chance were offered to him; and he also executed brass-plates for doors, with the names of the owners handsomely filled up, after the manner of the old “niellos,” with black sealing-wax. He engraved crests and initials on steel and silver watch-seals; also on tea-spoons, sugar-tongs, and other articles of plate; and the engraving of numerals and ornaments, with the name of the maker, on clock-faces,—which were not then enamelled,—seems to have formed one of the chief branches of his very general business.VII.31

475Bewick’s attention appears to have been first directed to wood engraving in consequence of his master having been employed by the late Dr. Charles Hutton, then a schoolmaster in Newcastle, to engrave on wood the diagrams for his Treatise on Mensuration. The printing of this work was commenced in 1768, and was completed in 1770. The engraving of the diagrams was committed to Bewick, who is said to have invented a graver with a fine groove at the point, which enabled him to cut the outlines by a single operation.

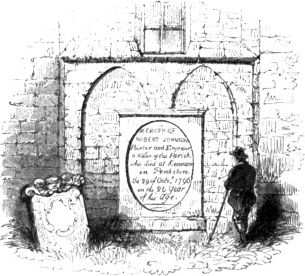

The above is a fac-simile of one of the earliest productions of Bewick in the art of wood engraving. The church is intended for that of St. Nicholas, Newcastle.

Subsequently, and while he was still an apprentice, Bewick undoubtedly endeavoured to improve himself in wood engraving; but his progress does not appear to have been great, and his master had certainly very little work of this kind for him to do. He appears to have engraved a few bill-heads on wood; and it is not unlikely that the cuts in a little book entitled “Youth’s Instructive and Entertaining Story Teller,” first published by T. Saint, Newcastle, 1774, were executed by him before the expiration of his apprenticeship.

Bewick, at one period during his apprenticeship, paid ninepence a week for his lodgings in Newcastle, and usually received a brown loaf every week from Cherry-burn. “During his servitude,” says Mr. Atkinson, “he paid weekly visits to Cherry-burn, except when the river was so much swollen as to prevent his passage of it at Eltringham, when he vociferated his inquiries across the stream, and then returned to Newcastle.” This account of his being accustomed to shout his enquiries 476 across the Tyne first appeared in a Memoir prefixed to the Select Fables, published by E. Charnley, 1820. Mr. William Bedlington, an old friend of Bewick, once asked him if it were true? “Babbles and nonsense!” was the reply. “It never happened but once, and that was when the river had suddenly swelled before I could reach the top of the allers,VII.32 and yet folks are made to believe that I was in the habit of doing it.”

On the expiration of his apprenticeship he returned to his father’s house at Cherry-burn, but still continued to work for Mr. Beilby. About this time he seems to have formed the resolution of applying himself exclusively in future to wood engraving, and with this view to have executed several cuts as specimens of his ability. In 1775 he received a premium of seven guineas from the Society of Arts for a cut of the Huntsman and the Old Hound, which he probably engraved when living at Cherry-burn after leaving Mr. Beilby.VII.33 The following is a fac-simile of this cut, which was first printed in an edition of Gay’s Fables, published by T. Saint, Newcastle, 1779. Mr. Henry Bohn, the publisher of the present edition, happening to be in possession of the original cut, it is annexed on the opposite page.

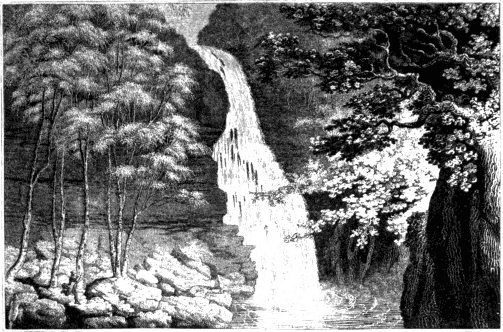

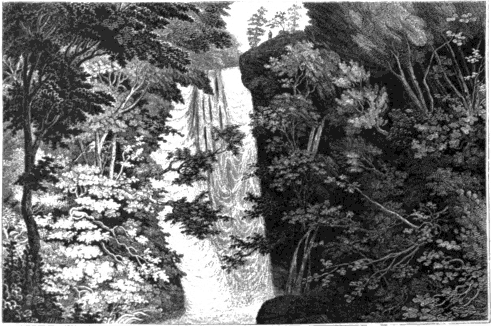

In 1776, when on a visit to some of his relations in Cumberland,VII.34 he availed himself of the opportunity of visiting the Lakes; and in after-life 477 he used frequently to speak in terms of admiration of the beauty of the scenery, and of the neat appearance of the white-washed, slate-covered cottages on the banks of some of the lakes. His tour was made on foot, with a stick in his hand and a wallet at his back; and it has been supposed that in a tail-piece, to be found at page 177 of the first volume of his British Birds, first edition, 1797, he has introduced a sketch of himself in his travelling costume, drinking out of what he himself would have called the flipe of his hat. The figure has been copied in our ornamental letter T at page 471.

In the same year, 1776, he went to London, where he arrived on the 1st of October. He certainly did not remain more than a twelvemonth in London,VII.35 for in 1777 he returned to Newcastle, and entered into partnership with his former master, Mr. Ralph Beilby. Bewick—who does not appear to have been wishful to undeceive those who fancied that he was the person who rediscovered the “long-lost art of engraving on wood”VII.36—would never inform any of the good-natured friends, who fished for intelligence with the view of writing his life, of the works on which he was employed when in London. The faith of a believer in the story of Bewick’s re-discovering “the long-lost art” would have received too great a shock had he been told by Bewick himself that 478 on his arrival in London he found professors of the “long-lost art” regularly exercising their calling, and that with one of them he found employment.

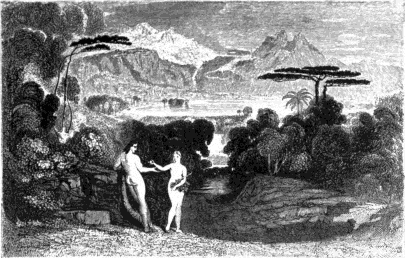

There is every reason to believe that Bewick, when in London, was chiefly employed by T. Hodgson, most likely the person who engraved the four cuts in Sir John Hawkins’s History of Music. It is at any rate certain that several cuts engraved by Bewick appeared in a little work entitled “A curious Hieroglyphick Bible,” printed by and for T. Hodgson, in George’s Court, St. John’s Lane, Clerkenwell.VII.37 Proofs of three of the principal cuts are now lying before me. The subjects are: Adam and Eve, with the Deity seen in the clouds, forming the frontispiece; the Resurrection; and a cut representing a gentleman seated in an arm-chair, with four boys beside him: the border of this cut is of the same kind as that of the large cut of the Chillingham Bull engraved by Bewick in 1789. These proofs appear to have been presented by Bewick to an eminent painter, now dead, with whom either then, or at a subsequent period, he had become acquainted. Not one of Bewick’s biographers mentions those cuts, nor seems to have been aware of their existence. The two memoirs of Bewick, written by his “friends” G. C. Atkinson and John F. M. Dovaston,VII.38 sufficiently demonstrate that neither of them had enjoyed his confidence in matters relative to his progress in the art of wood engraving.

Mr. Atkinson, in his Sketch of the Life and Works of Bewick, says that when in London he worked with a person of the name of Cole. Of this person, as a wood engraver, I have not been able to discover any trace. Bewick did not like London; and he always advised his former pupils and north-country friends to leave the “province covered with houses” as soon as they could, and return to the country to there enjoy the beauties of Nature, fresh air, and 479 content. In the letter to his old schoolfellow, Mr. Christopher Gregson, previously quoted, he thus expresses his opinion of London life. “Ever since you paid your last visit to the north, I have often been thinking upon you, and wishing that you would lap up, and leave the metropolis, to enjoy the fruits of your hard-earned industry on the banks of the Tyne, where you are so much respected, both on your own account and on that of those who are gone. Indeed, I wonder how you can think of turmoiling yourself to the end of the chapter, and let the opportunity slip of contemplating at your ease the beauties of Nature, so bountifully spread out to enlighten, to captivate, and to cheer the heart of man. For my part, I am still of the same mind that I was in when in London, and that is, I would rather be herding sheep on Mickley bank top than remain in London, although for doing so I was to be made the premier of England.” Bewick was truly a country man; he felt that it was better “to hear the lark sing than the mouse cheep;” for, though no person was capable of closer application to his art when within doors, he loved to spend his hours of relaxation in the open air, studying the character of beasts and birds in their natural state; and diligently noting those little incidents and traits of country life which give so great an interest to many of his tail-pieces. When a young man, he was fond of angling; and, like Roger Ascham, he “dearly loved a main of cocks.” When annoyed by street-walkers in London, he used to assume the air of a stupid countryman, and, in reply to their importunity, would ask, with an expression of stolid gravity, if they knew “Tommy Hummel o’ Prudhoe, Willy Eltringham o’ Hall-Yards, or Auld Laird Newton o’ Mickley?”VII.39 He thus, without losing his temper, or showing any feeling of annoyance, soon got quit of those who wished to engage his attention, though sometimes not until he had received a hearty malediction for his stupidity.

In 1777, on his return to Newcastle, he entered into partnership with Mr. Beilby; and his younger brother, John Bewick, who was then about seventeen years old, became their apprentice. From this time Bewick, though he continued to assist his partner in the other branches of their business,VII.40 applied himself chiefly to engraving on 480 wood. The cuts in an edition of Gay’s Fables, 1779,VII.41 and in an edition of Select Fables, 1784, both printed by T. Saint, Newcastle, were engraved by Bewick, who was probably assisted by his brother. Several of those cuts are well engraved, though by no means to be compared to his later works, executed when he had acquired greater knowledge of the art, and more confidence in his own powers. He evidently improved as his talents were exercised; for the cuts in the Select Fables, 1784, are generally much superior to those in Gay’s Fables, 1779; the animals are better drawn and engraved; the sketches of landscape in the back-grounds are more natural; and the engraving of the foliage of the trees and bushes is, not unfrequently, scarce inferior to that of his later productions. Such an attention to nature in this respect is not to be found in any wood-cuts of an earlier date. The following impressions from two of the original cuts in the Select Fables are fair specimens; one is interesting, as being Bewick’s first idea of a favourite vignette in his British Land 481 Birds; the other as his first treatment of the lion and the four bulls, afterwards repeated in his Quadrupeds. In the best cuts of the time of Durer and Holbein the foliage is generally neglected; the artists of that period merely give general forms of trees, without ever attending to that which contributes so much to their beauty. The merit of introducing this great improvement in wood engraving, and of depicting quadrupeds and birds in their natural forms, and with their characteristic expression, is undoubtedly due to Bewick. Though he was not the discoverer of the art of wood engraving, he certainly was the first who applied it with success to the delineation of animals, and to the natural representation of landscape and woodland scenery. He found for himself a path which no previous wood engraver had trodden, and in which none of his successors have gone beyond him. For several of the cuts in the Select Fables, Bewick was paid only nine shillings each.

In 1789 he drew and engraved his large cut of the Chillingham Bull,VII.42 which many persons suppose to be his master-piece; but though it is certainly well engraved, and the character of the animal is well expressed, yet as a wood engraving it will not bear a comparison with several of the cuts in his History of British Birds. The grass and the foliage of the trees are most beautifully expressed; but there is a want of variety in the more distant trees, and the bark of that in the fore-ground to the left is too rough. This exaggeration of the roughness of the bark of trees is also to be perceived in many of his other cuts. The style in which the bull is engraved is admirably adapted to express the texture of the short white hair of the animal; the dewlap, however, is not well represented, it appears to be stiff instead of flaccid and pendulous; and the lines intended for the hairs on its margin are too wiry. On a stone in the fore-ground he has introduced a bit of cross-hatching, but not with good effect, for it causes the stone to look very much like an old scrubbing-brush. Bewick was not partial to cross-hatching, and it is seldom to be found in cuts of his engraving. He seems to have introduced it in this cut rather to show to those who knew anything of the matter that he could engrave such lines, than from an opinion that they were necessary, or in the slightest degree improved the cut. This is almost the only instance in which Bewick has introduced black lines crossing each other, and thus forming what is usually called “cross-hatchings.” From the commencement of his career as a wood engraver, he adopted a much more simple method of obtaining colour. He very justly considered, that, as impressions of wood-cuts are printed from lines engraved in relief, the unengraved 482 surface of the block already represented the darkest colour that could be produced; and consequently, instead of labouring to produce colour in the same manner as the old wood engravers, he commenced upon colour or black, and proceeded from dark to light by means of lines cut in intaglio, and appearing white when in the impression, until his subject was completed. This great simplification of the old process was the result of his having to engrave his own drawings; for in drawing his subject on the wood he avoided all combinations of lines which to the designer are easy, but to the engraver difficult. In almost every one of his cuts the effect is produced by the simplest means. The colour which the old wood engravers obtained by means of cross-hatchings, Bewick obtained with much greater facility by means of single lines, and masses of black slightly intersected or broken with white.

When only a few impressions of the Chillingham Bull had been taken, and before he had added his name, the block split. The pressmen, it is said, got tipsy over their work, and left the block lying on the window-sill exposed to the rays of the sun, which caused it to warp and split.VII.43 About six impressions were taken on thin vellum before the accident occurred. Mr. Atkinson says that one of those impressions, which had formerly belonged to Mr. Beilby, Bewick’s partner, was sold in London for twenty pounds; A. Stothard, R.A., had one, as had also Mr. C. Nesbit.

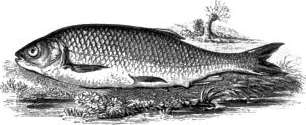

Towards the latter end of 1785 Bewick began to engrave the cuts for his General History of Quadrupeds, which was first printed in 1790.VII.44 The descriptions were written by his partner, Mr. Beilby, and the cuts were all drawn and engraved by himself. The comparative excellence of those cuts, which, for the correct delineation of the animals and the natural character of the incidents, and the back-grounds, are greatly superior to anything of the kind that had previously appeared, insured a rapid sale for the work; a second edition was published in 1791, and a third in 1792.VII.45

The great merit of those cuts consists not so much in their execution as in the spirited and natural manner in which they are drawn. Some of the animals, indeed, which he had not had an opportunity of seeing, and for which he had to depend on the previous engravings of others, are not correctly drawn. Among the most incorrect are the Bison, the 483 Zebu, the Buffalo, the Many-horned Sheep, the Gnu, and the Giraffe or Cameleopard.VII.46 Even in some of our domestic quadrupeds he was not successful; the Horses are not well represented; and the very indifferent execution of the Common Bull and Cow, at page 19, edition 1790, is only redeemed by the interest of the back-grounds. In that of the Common Bull, the action of the bull seen chasing a man is most excellent; and in that of the Cow, the woman, with a skeel on her head, and her petticoats tucked up behind, returning from milking, is evidently a sketch from nature. The Goats and the Dogs are the best of those cuts both in design and execution; and perhaps the very best of all the cuts in the first edition is that of the Cur Fox at page 270. The tail of the animal, which is too long, and is also incorrectly marked with black near the white tip, was subsequently altered.