erhaps no art exercised in this country is

less known to the public than that of wood engraving; and hence it

arises that most persons who have incidentally or even expressly written

on the subject have committed so many mistakes respecting the practice.

It is from a want of practical knowledge that we have had so many absurd

speculations respecting the manner in which the old wood engravers

executed their cross-hatchings, and so many notions about

vegetable putties and metallic relief engraving. Even in a Memoir of

Bewick, printed in 1836, we find the following passage, which certainly

would not have appeared had the writer paid any attention to the

numerous wood-cuts, containing cross-hatchings of the most delicate

kind, published in England between 1820 and 1834:—“The principal

characteristic of the ancient masters is the crossing of the black

lines, to produce or deepen the shade, commonly called

cross-hatching. Whether this was done by employing different

blocks, one after another, as in calico-printing and paper-staining,

it may be difficult to say; but to produce them on the same block

is so difficult and unnatural, that though Nesbit, one of

Bewick’s early pupils, attempted it on a few occasions, and the splendid

print of Dentatus by Harvey shows that it is not impossible even on a

large scale, yet the waste

562

of time and labour is scarcely worth the effect produced.”IX.1 Now, the

difficulty of saying whether the old cross-hatchings were executed on a

single block, or produced by impressions from two or more, proceeds

entirely from the writer not being acquainted with the subject; had he

known that hundreds of old blocks containing cross-hatchings are still

in existence, and had he been in the habit of seeing similar

cross-hatchings executed almost daily by very indifferent wood

engravers, the difficulty which he felt would have vanished. “Unnatural”

is certainly an improper term for a philosopher to apply to a

process of art, merely because he does not understand it: with equal

reason he might have called every other process, both of copper-plate

and wood engraving, “unnatural;” nay, in this sense there is no process

in arts or manufactures to which the term “unnatural” might not in the

same manner be applied.

erhaps no art exercised in this country is

less known to the public than that of wood engraving; and hence it

arises that most persons who have incidentally or even expressly written

on the subject have committed so many mistakes respecting the practice.

It is from a want of practical knowledge that we have had so many absurd

speculations respecting the manner in which the old wood engravers

executed their cross-hatchings, and so many notions about

vegetable putties and metallic relief engraving. Even in a Memoir of

Bewick, printed in 1836, we find the following passage, which certainly

would not have appeared had the writer paid any attention to the

numerous wood-cuts, containing cross-hatchings of the most delicate

kind, published in England between 1820 and 1834:—“The principal

characteristic of the ancient masters is the crossing of the black

lines, to produce or deepen the shade, commonly called

cross-hatching. Whether this was done by employing different

blocks, one after another, as in calico-printing and paper-staining,

it may be difficult to say; but to produce them on the same block

is so difficult and unnatural, that though Nesbit, one of

Bewick’s early pupils, attempted it on a few occasions, and the splendid

print of Dentatus by Harvey shows that it is not impossible even on a

large scale, yet the waste

562

of time and labour is scarcely worth the effect produced.”IX.1 Now, the

difficulty of saying whether the old cross-hatchings were executed on a

single block, or produced by impressions from two or more, proceeds

entirely from the writer not being acquainted with the subject; had he

known that hundreds of old blocks containing cross-hatchings are still

in existence, and had he been in the habit of seeing similar

cross-hatchings executed almost daily by very indifferent wood

engravers, the difficulty which he felt would have vanished. “Unnatural”

is certainly an improper term for a philosopher to apply to a

process of art, merely because he does not understand it: with equal

reason he might have called every other process, both of copper-plate

and wood engraving, “unnatural;” nay, in this sense there is no process

in arts or manufactures to which the term “unnatural” might not in the

same manner be applied.

In giving some account of the practice of wood engraving, it seems most proper to begin with the ground-work—the wood. As it is generally understood that box is best adapted for the purposes of engraving, and that it is generally used for cuts intended for the illustration of books, there seems no occasion to enter into a detail of all the kinds of wood that might be used for the more ordinary purposes of large coarse cuts for posting-bills, and others of a similar character. Mr. Savage, in his Hints on Decorative Printing, has copied the principal part of what Papillon has said on the subject of wood, intending that it should be received as information from a practical wood engraver; but he has omitted to notice that much of what Papillon says about the choice of wood, can be of little service in guiding the modern English wood engraver, who executes his subject on the cross-section of the wood, while Papillon and his contemporaries were accustomed to engrave upon the side, or the long-way of the wood. “There is no difficulty,” says Papillon, as translated by Mr. Savage, “in distinguishing that which is good, as we have only need of taking a splinter of the box we wish to try, and break it between the fingers; if it break short, without bending, it will not be of any value; whereas, if there be great difficulty in breaking it, it is well adapted to our purpose.”

Now, it is quite evident from this direction—independent of the fact being otherwise known—that the thin splinter by which the quality of the wood was to be tested was to be cut the long way of the wood: a similar cutting taken from the cross-section would break short, however excellent the wood might be for the purpose of engraving. Papillon’s direction is therefore calculated to mislead, unless accompanied with an explanation of the manner in which the splinter is to be taken; and it 563 is also utterly useless as a test of box that is intended to be engraved on the cross-section, or end-way of the wood.

For the purposes of engraving no other kind of wood hitherto tried is equal to box. For fine and small cuts the smallest logs are to be preferred, as the smallest wood is almost invariably the best. American and Turkey box is the largest; but all large wood of this kind is generally of inferior quality, and most liable to split; it is also frequently of a red colour, which is a certain characteristic of its softness, and consequent unfitness for delicate engraving. From my own experience, English box is superior to all others; for though small, it is generally so clear and firm in the grain that it never crumbles under the graver; it resists evenly to the edge of the tool, and gives not a particle beyond what is actually cut out. The large red wood, on the contrary, besides being soft, is liable to crumble and to cut short; that is, small particles will sometimes break away from the sides of the line cut by the graver, and thus cause imperfections in the work. Box of large and comparatively quick growth, is also extremely liable to shrink unevenly between the rings, so that after the surface has been planed perfectly level, and engraved, it is frequently difficult to print the cut in a proper manner, in consequence of the inequality of the surface.

As even the largest logs of box are of comparatively small diameter, it is extremely difficult to obtain a perfect block of a single piece equal to the size of an octavo page. In order to obtain pieces as large as possible, some dealers are accustomed to saw the log in a slanting direction—in the manner of an oblique section of a cylinder—so that the surface of a piece cut off shall resemble an oval rather than a circle. Blocks sawn in this manner ought never to be used; for, in consequence of the obliquity of the grain, there is no preventing small particles tearing out when cutting a line.

Large red wood containing white spots or streaks is utterly unfit for the purposes of the engraver; for in cutting a line across, adjacent to these spots or streaks, sometimes the entire piece thus marked will be removed, and the cut consequently spoiled. A clear yellow colour, and as equal as possible over the whole surface, is generally the best criterion of box-wood. When a block is not of a clear yellow colour throughout, but only in the centre, gradually becoming lighter towards the edges, it ought not to be used for delicate work; the white, in addition to its not cutting so “sweetly,” being of a softer nature, absorbs more ink than the yellow, and also retains it more tenaciously, so that impressions from a block of this kind sometimes display a perceptible inequality of colour;—from the yellow parts allowing the ink to leave them freely, while the white parts partially retain it, the printed cut has the appearance of having received either too much ink in one place, or too 564 little in another. Besides this, the ink remaining on the white parts becomes so adhesive, that, should the sheet be rather too damp (as will frequently happen when much paper is wetted at one time), it will sometimes stick to the paper; a small spot of white will hence appear in the impression, while a minute piece of paper will remain adhering to the block, to be mixed up with the ink on the balls, and transferred as a black speck to another part of the cut in a subsequent impression. But this is not all: should the piece of paper remain unnoticed for some time it will make a small indention in the block, and occasion a white or grey speck in the impressions printed after its removal. Soft red and white box, more especially the latter, being more porous than clear yellow, blocks of those kinds of wood are most liable to be injured by the liquids used to clean them after printing. Should the printer wash them with either lees or spirits of turpentine, these fluids will enter the wood more freely than if it were yellow, and cause it to expand in proportion to the quantity used, and sometimes to such an extent as to distort the drawing. If a block of any kind of box, whether red, white, or yellow, be wetted or exposed to dampth, it will expand considerably;IX.2 but with care it will return to its former dimensions, should it have been sufficiently seasoned before being printed. When, however, the expansion has been caused by lees or spirits of turpentine, the block will never again contract to its original size.IX.3

As publishers frequently provide the drawings which are to be engraved, perhaps a knowledge of the different qualities of box is as necessary to them as to wood engravers themselves. In reply to this it may be said, why not require the engraver who is to execute the cuts to supply proper wood himself? Where only one engraver is employed to execute all the cuts for a work, the choice of the wood may indeed be very properly left to himself. But where several are employed, and each required to send his own wood to the designer, very few are particular what kind they send; for when the designer receives the different pieces he generally consigns them to a drawer until wanted, and when he has finished a design, he not unfrequently sends it to an engraver who did 565 not supply the identical piece of wood on which it is drawn. Hence scarcely any engraver pays much attention to the kind of wood he sends; for where many are employed in the execution of a series of cuts for the same work, it is very unlikely that each will receive the drawings on the wood supplied by himself. Even when the designer is particular in making the drawings of the subjects which he thinks best suited to each engraver’s talents on the wood which such engraver has supplied, it not unfrequently happens that the person who employs the engravers will not give the blocks to those for whom the artist intended them. Publishers have a much greater interest in this matter than they seem to suspect. If soft wood be supplied, the finer lines will soon be bruised down in printing, and the cut will appear like an old one before half the number of impressions required have been printed; if red-ringed, the surface is extremely liable to become uneven, and also to warp and split.

As box can seldom be obtained of more than five or six inches diameter, and as wood of this size is rarely sound throughout, blocks for cuts exceeding five inches square are usually formed of two or more pieces firmly united by means of iron pins and screws. Should the block, however, be wetted or exposed to dampth, the joints are certain to open, and sometimes to such an extent as to require a piece of wood to be inserted in the aperture.IX.4 Perhaps the best way to guard against a large block opening at the joining of the pieces would be to enclose it with an iron hoop or frame; such hoop or frame being fixed when nearly red-hot in the same manner as a tire is applied to a coach or cart wheel. If the iron fit perfectly tight when forced on to the block in the manner of a tire, it will be the more likely, by its contracting in cold and damp weather, to resist the expansive force of the wood at such times.

Besides the hardness and toughness of box, which allows of clear raised lines, capable of bearing the action of the press, being cut on its surface, this wood, from its not being subject to the attacks of the worm, has a great advantage over apple, pear-tree, beech,IX.5 and other kinds of wood, formerly used for the purposes of engraving. Its preservation in this respect is probably owing to its poisonous nature, for other kinds of wood of greater hardness and durability are frequently pierced through and through by worms. The chips of box, when chewed, are certainly unwholesome to human beings. A fellow-pupil, who had acquired a habit of chewing the small pieces which he cut out with his graver, 566 became unwell, and was frequently attacked with sickness. On mentioning the subject to his medical adviser, he was ordered to refrain from chewing the pieces of box; he accordingly took the doctor’s advice, gave up his bad habit, and in a short time recovered his usual health.IX.6

Box when kept long in a dry place becomes unfit for the purpose of engraving. I have at this time in my possession a drawing which has been made on the block about ten years, but the wood has become so dry and brittle that it would now be impossible to engrave the subject in a proper manner.

When the wood does not cut clear, but crumbles as if it were too dry, the defect may sometimes be remedied by putting the block into a deep earthenware jug or pan, and placing such jug or pan in a cool place for ten or twelve hours. When the wood is too hard and dry to be softened in the above manner, I would recommend that the back of the block should be placed in water—in a plate or large dish—to the depth of the sixteenth part of an inch, for about an hour. If allowed to remain longer there is a risk of the block afterwards splitting.

Box, of whatever kind, when not well seasoned, is extremely liable to warp and bend; but a little care will frequently prevent many of the accidents to which drawings on unseasoned wood are exposed by neglect. For instance, when a block is received by the engraver from the designer or publisher, it ought, if not directly put in hand, to be placed on one of its edges, and not, as is customary with many, laid down flat, with the surface on which the drawing is made upwards. If a block of unseasoned wood be permitted to lie in this manner for a week or two, it is almost certain to turn up at the edges, the upper surface becoming concave, and the lower convex, as is shown in the annexed cut, representing the section of such a block.

The same thing will occur in the process of engraving, though to a small extent, should the engraver’s hands be warm and moist; and also when working by lamp-light without a globe filled with water between the lamp and the block. Such slight warping in the course of engraving is, however, easily remedied by laying the block with its face—that is, the surface on which the drawing is made—downward on the desk or table at all times when the engraver is not actually employed on the 567 subject. The block so placed, provided that it be not of very dry wood, in a short time recovers its former level. When a block of very dry wood becomes dished, or concave, on its upper surface, as shown in the preceding cut, there is little chance of its ever again becoming sufficiently flat to allow of its being well printed. When the deviation from a perfect level at the bottom is not so great as to attract the notice of the pressman previous to taking an impression, the block not unfrequently yields to the action of the platten, and splits. The fracture remains perhaps unobserved for a short time, and when it is at length noticed, the block is probably spoiled beyond remedy.

When box is very dry it is extremely difficult to cut a clear line upon it, as it crumbles, and small pieces fly out at the sides of the line traced by the graver. The small white spots so frequently seen in the delicate lines of the sky in wood-cuts are occasioned by particles flying out in this manner. If a block consist partly of yellow wood and partly of wood with red rings, the yellow will cut clear, while in the red it will be almost impossible to cut a perfect line. When the same piece of wood is yellow and red alternately it is extremely difficult to produce an even tint upon it. Wood of this kind ought always to be rejected, both from the difficulty of engraving upon it with clearness, and from the uncertainty of the surface continuing perfectly flat, as the red rings are more liable to shrink in drying than the other parts, and, from their thus not receiving a sufficient quantity of ink, to appear like so many rainbows in the impression.

The spaces between those rings are greater or less, accordingly as the seasons have been favourable or unfavourable to the growth of the tree. Besides the injurious effect which those red rings are apt to produce in an impression, wood of this kind is very unpleasant and uncertain to engrave on; for as the yellow parts cut pleasant and clear, the engraver, unless particularly on his guard, is betrayed to trust to the whole piece as being of the same uniform tenacity, and before he is aware of its inequality in this respect, or can check the progress of his graver, its point has entered one of those soft red rings, and, to the injury of his work, has either caused a small piece to fly out, or carried the line further than he intended. Wood of this kind is unfit for anything except very common work, and ought never to be used for delicate engraving. There is no certain means of forming a judgment of box-wood until it be cut into slices or trencher-like pieces from the log; for many logs which externally appear sound and of a good colour, prove very faulty and cracked in the centre when sawn up. Turkey box is in particular so defective in this respect that a large slice can seldom be procured without a crack. This, probably, is occasioned by the manner in which the tree is felled. Previous to their beginning to cut down 568 a tree the Turkish wood-cutters fasten a rope to the top, by means of which they break the tree down when the bole is little more than half cut through. The consequence is that a shiver frequently extends through the most valuable portion of the log.

Many artists, who are not accustomed to make drawings on wood, erroneously suppose that the block requires some peculiar preparation. Nothing more is required than to rub the previously planed and smoothed surface with a little powdered Bath-brick, slightly mixed with water: as little water as possible is, however, to be used, as otherwise the block will absorb too much, and be afterwards extremely liable to split. When this thin coating is perfectly dry, it is to be removed by rubbing the block with the palm of the hand. No part of the light powder ought to remain, for, otherwise, the pencil coming in contact with it will make a coarse and comparatively thick line, which, besides being a blemish in the drawing, is very liable to be rubbed off. The object of using the powdered Bath-brick is to render the surface less slippery, and thus capable of affording a better hold to the point of the black-lead pencil.

When the principal parts of the drawing are first washed in upon the block in Indian ink, it is of great advantage to gently rub the surface of the block, when dry, with a little dry and finely powdered Bath-brick, before the drawing is completed with the black-lead pencil. By this means the hard edges of the Indian-ink wash will be softened, the different tints delicately blended, and the subsequent touches of the pencil be more distinctly seen. Some artists, previous to beginning to draw on the block, are in the habit of washing over the surface with a mixture of flake-white and gum-water.IX.7 This practice is, however, by no means a good one. The drawing indeed may appear very bright and showy when first made on such a white surface, but in the progress of engraving a thin film of the preparation will occasionally rise up before the graver and carry with it a portion of the unengraved work, which the engraver is left to restore according to his ability and recollection. This white ground also mixes with the ink in taking a first proof, and fills up the finer parts of the cut. If a white wash be used without gum, the drawing is very liable to be partially effaced in the progress of engraving, and the engraver left to finish his work as he can. The risk of this inconvenience ought to be especially avoided in making drawings on a block, as the wood engraver has not the opportunity of referring to another drawing or to an original painting in the manner of an engraver on copper.

569The less that is done to change the original colour of the wood—by white or any other preparation—so much the better for the engraver; a piece of clear box is sufficiently light to allow of the most delicate lines being distinctly drawn upon it. When the surface of the block is whitened, another inconvenience arises besides those already noticed. It is this: when the drawing is made upon a white ground, and the subject partially engraved, the effect of the whole becomes very confused and perplexing to the engraver in consequence of the parts already engraved appearing nearly of the original colour of the wood, while the ground of the parts not yet cut is white, as first drawn. The engraver’s eye cannot correctly judge of the whole, and the inconvenience is increased by his neither having an original drawing to refer to, nor a proof to guide him: until the cut be completed he has no means of correctly ascertaining whether he has left too much colour or taken too much away.

The engraver on copper or on steel can have an impression of his etching as soon as it is bit in, and can take impressions of the plate at all times in the course of his progress; the wood engraver, on the contrary, enjoys no such advantages; he is obliged to wait until all be completed ere he can obtain an impression of his work. If the wood engraver has kept his subject generally too dark, there is not much difficulty in reducing it; but if he has engraved it too light, there is no remedy. If a small part be badly engraved, or the block has sustained an injury, the defect may be repaired by inserting a small piece of wood and re-engraving it: this mode of repairing a block is technically termed “plugging.”IX.8

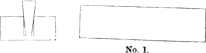

When a block requires to be thus amended or repaired, it is first to be determined how much is necessary to be taken out that the restoration may accord with the adjacent parts; for sometimes, in order to render the insertion less perceptible, it may be requisite to take out rather more than the part imactually perfect or injured. This being decided on, a hole is drilled in the block, as is represented in the next page, of a size sufficient to admit “the plug.” The hole ought not to be drilled quite through the block, as the piece let in would, from the shaking and battering of the press, be very likely to become loosened. Should it receive more pressure at the top than bottom, it would sink a little below the engraved surface of the block, and thus appear lighter in the impression than the surrounding parts; while should it be slightly forced up from below it, would appear darker,—in each case forming 570 a positive blemish in the cut.IX.9 When the shape of the part to be restored is too large to be covered with one circular plug, it is better to add one plug to another till the whole be covered, than to insert one of a different shape, and thus fill the space at once. When a single plug is used the section appears thus;

the plug being driven in like a wedge, and having a vacant space around it at the bottom. If an oblong space of the form No. 1. is to be restored, it will be best effected by first inserting a plug at each end, as at No. 2, then adding two others, as at No. 3, and finally wedging them all fast by a central plug, as at No. 4, like the key-stone in an arch. When a plug is firmly fixed, the top is carefully cut down to the level of the block, and the part of the subject wanting re-drawn and engraved. When these operations are well performed no trace of the insertion can 571 be discovered, except by one who should know where to look for it.

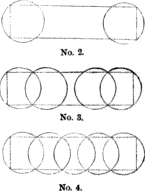

THE PLUG OUT.

When a cast is taken from a block which requires the insertion of a plug, the best mode is to have the part intended to be renewed cast blank. In this case a hole of sufficient size is to be drilled in the block, and afterwards filled up with plaster to the level of the surface. A cast being then taken, the part to be re-engraved remains blank, but of a piece with the rest of the metal, so that there is no possibility of its rising up above or sinking below the surface, as sometimes happens when a plug is inserted in a wood-block. When the part remaining blank in the cast is engraved in accordance with the work of the surrounding parts, it is almost impossible to discover any trace of the insertion. The following impression is from a cast of the block illustrating the “plug,” with the part which appears white in the former cut restored and re-engraved in this manner. A white circular line, near the handle of the pail, has been purposely cut to indicate the place of the plug.

Before beginning to engrave any subject, it is necessary to observe whether the drawing be entirely, or only in part, made with a pencil. If it be what is usually called a wash drawing, with little more than the outlines in pencil, it is not necessary to be so cautious in defending it from the action of the breath or the occasional touching of the hand; 572 but if it be entirely in pencil, too much care cannot be taken to protect it from both.

Before proceeding to engrave a delicate pencil drawing the block ought to be covered with paper, with the exception of the part on which it is intended to begin. Soft paper ought not to be used for this purpose, as such is most likely to partially efface the drawing when the hand is pressed upon the block. Moderately stout post-paper with a glazed surface is the best; though some engravers, in order to preserve their eyes, which become affected by white paper, cover the block with blue paper, which is usually too soft, and thus expose the drawing to injury. The dingy, grey, and over-done appearance of several modern wood-cuts is doubtless owing, in a great measure, to the block when in course of engraving having been covered with soft paper, which has partially effaced the drawing. The drawing, which originally may have been clear and touchy, loses its brightness, and becomes indistinct from its frequent contact with the soft pliable paper; the spirited dark touches which give it effect are rubbed down to a sober grey, and all the other parts, from the same cause, are comparatively weak. The cut, being engraved according to the appearance of the drawing, is tame, flat, and spiritless.

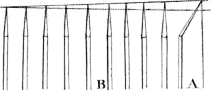

Different engravers have different methods of fastening the paper to the block.IX.10 Some fix it with gum, or with wafers at the sides; but this is not a good mode, for as often as it is necessary to take a view of the whole block, in order to judge of the progress of the work, the paper must be torn off, and afterwards replaced by means of new wafers or fresh gum, so that before the cut is finished the sides of the block are covered with bits of paper in the manner of a wall or shop-front covered with fragments of posting-bills. The most convenient mode of fastening the paper is to first wrap a piece of stiff and stout thread three or four times round the edges of the block, and then after making the end fast to remove it. The paper is then to be closely fitted to the block, and the edges being brought over the sides, the thread is to be re-placed above it. If the turns of the thread be too tight to pass over the last corner of the block, A, a piece of string, B, being passed within them and firmly pulled, in the manner here represented, will cause them to stretch a little and pass over on to the edge without difficulty. When this plan is adopted the paper forms a kind of moveable cap, which can 573 be taken off at pleasure to view the progress of the work, and replaced without the least trouble.

I have long been of opinion that many young persons, when beginning to learn the art of wood engraving, have injured their sight by unnecessarily using a magnifying glass. At the very commencement of their pupilage boys will furnish themselves with a glass of this kind, as if it were as much a matter of course as a set of gravers; they sometimes see men use a glass, and as at this period they are prone to ape their elders in the profession, they must have one also; and as they generally choose such as magnify most, the result not unfrequently is that their sight is considerably impaired before they are capable of executing anything that really requires much nicety of vision.

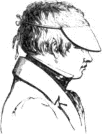

I would recommend all persons to avoid the use of glasses of any kind, whether single magnifiers or spectacles, until impaired sight renders such aids necessary; and even then to commence with such as are of small magnifying power. The habit of viewing minute objects alternately with a magnifying glass and the naked eye—applying the glass every two or three minutes—is, I am satisfied, injurious to the sight. The magnifying glass used by wood engravers is similar to that used by watch-makers, and consists of a single lens, fitted into a short tube, which is rather wider at the end applied to the eye. As the glass seldom can be fixed so firmly to the eye as to entirely dispense with holding it, the engraver is thus frequently obliged to apply his left hand to keep it in its place; as he cannot hold the block with the same hand at the same time, or move it as may be required, so as to enable him to execute his work with freedom, the consequence is, that the engraving of a person who is in the habit of using a magnifying glass has frequently a cramped appearance. There are also other disadvantages attendant on the habitual use of a magnifying glass. A person using such a glass must necessarily hold his head aside, so that the eye on which the glass is fixed may be directly above the part on which he is at work. In order to attain this position, the eye itself is not unfrequently distorted; and when it is kept so for any length of time it becomes extremely painful. I never find my eyes so free from pain or aching as when looking at the work directly in front, without any twisting of the neck so as to bring one eye only immediately above the part in course of execution. I therefore conclude that the eyes are less likely to be injured when thus employed than when one is frequently distorted and pained in looking through a glass. I am here merely speaking from experience, and not professedly from any theoretic knowledge of optics; but as I have hitherto done without the aid of any magnifying power, I am not without reason convinced that glasses of all kinds ought to be dispensed with until impaired vision renders their use absolutely 574 necessary. I am decidedly of opinion that to use glasses to preserve the sight, is to meet half way the evil which is thus sought to be averted. A person who has his sense of hearing perfect never thinks of using a trumpet or acoustic instrument in order to preserve it. All wood engravers, whether their eyes be naturally weak or not, ought to wear a shade, similar to that represented in the following figure, No. 1, as it both protects the eyes from too strong a light, and also serves to concentrate the view on the work which the engraver is at the time engaged in executing.

When speaking on this subject, it may not be out of place to mention a kind of shade or screen for the nose and mouth, similar to that in the preceding figure, No. 2. Such a shade or screen is called by Papillon a mentonnière,IX.11 and its object is to prevent the drawing on the block being injured by the breath in damp or frosty weather. Without such a precaution, a drawing made on the block with black-lead pencil would, in a great measure, be effaced by the breath of the engraver passing freely over it in such weather. Such a shade or screen is most conveniently made of a piece of thin pasteboard or stiff paper.

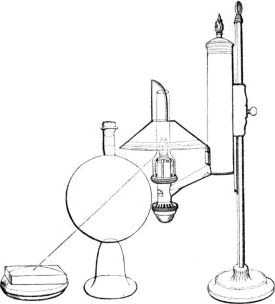

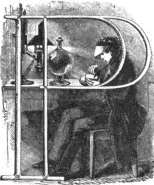

There are various modes of protecting the eyes when working by lamp-light, but I am aware of only one which both protects the eyes from the light and the face from the heat of the lamp. This consists in filling a large transparent glass-globe with clear water, and placing it in such a manner between the lamp and the workman that the light, after passing through the globe, may fall directly on the block, in the manner represented in the following cut. The height of the lamp can be regulated according to the engraver’s convenience, in consequence of its being moveable on the upright piece of iron or other metal which forms its support. The dotted line shows the direction of the light when the lamp is elevated to the height here seen; by lowering the lamp a 575 little more, the dotted line would incline more to a horizontal direction, and enable the engraver to sit at a greater distance. By the use of those globes one lamp will suffice for three or four persons, and each person have a much clearer and cooler light than if he had a lamp without a globe solely to himself.IX.12

It has been said, and with some appearance of truth, that “the best engravers use the fewest tools;” but this, like many other sayings of a similar kind, does not generally hold good. He undoubtedly ought to be considered the best engraver who executes his work in the best manner with the fewest tools; while it is no less certain that he is a bad engraver who executes his work badly, whether he use many or few. No wood engraver who understands his art will incumber his desk or table with a number of useless tools, though, from a regard to his own time, he will take care that he has as many as are necessary. There are some who pride themselves upon executing a great variety of work with one 576 tool, and hence, firmly believing in the truth of the saying above quoted, fancy that they are first-rate engravers. Such would be better entitled to the name if they executed their work well. A person who makes his tools his hobby-horse, and who bestows upon their ornaments—ebony or ivory handles, silver hoops, &c.—that attention which ought rather to be devoted to his subject, rarely excels as an engraver. He who is vain of the beautiful appearance of his tools has not often just reason to be proud of his work.

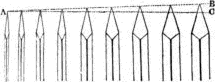

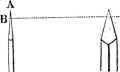

There are only four kinds of cutting toolsIX.13 necessary in wood engraving, namely:—gravers; tint-tools; gouges or scoopers; and flat tools or chisels. Of each of these four kinds there are various sizes. The following cut shows the form of a graver that is principally used for outlining or separating one figure from another. A, is the back of the tool; B, the face; C, the point; and D, what is technically called the belly. The horizontal dotted line, 1, 2, shows the surface of the block, and the manner in which part of the handle is cut off after the blade is inserted.IX.14 This tool is very fine at the point, as the line which it cuts ought to be so thin as not to be distinctly perceptible when the cut is printed, as the intention is merely to form a termination or boundary to a series of lines running in another direction. Though it is necessary that the point should be very fine, yet the blade ought not to be too thin, for then, instead of cutting out a piece of the wood, the tool will merely make a delicate opening, which would be likely to close as soon as the block should be exposed to the action of the press. When the outline tool becomes too thin at the point the lower part should be rubbed on a hone, in order to reduce the extreme fineness.

About eight or nine gravers of different sizes, beginning from the outline tool, are generally sufficient. The blades differ little in shape, when first made, from those used by copper-plate engravers; but in order to render them fit for the purpose of wood engraving, it is necessary to give the points their peculiar form by rubbing them on a Turkey stone. In this cut are shown the faces and part of the backs of nine gravers of different sizes; the lower dotted line, A C, shows the extent to which the points of such 577 tools are sometimes ground down by the engraver in order to render them broader. When thus ground down the points are slightly rounded, and do not remain straight as if cut off by the dotted line A C. These tools are used for nearly all kinds of work, except for series of parallel lines, technically called “tints.” The width of the line cut out, according to the thickness of the graver towards the point, is regulated by the pressure of the engraver’s hand.

TINT-TOOL.

GRAVER.

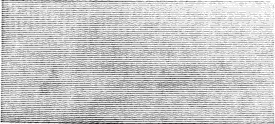

Tint-tools are chiefly used to cut parallel lines forming an even and

uniform tint, such as is usually seen in the representation of a

clear sky in wood-cuts. They are thinner at the back, but deeper in the

side than gravers, and the angle of the face, at the point, is much more

acute. About seven or eight, of different degrees of fineness, are

generally sufficient. The following cut will afford an idea of the shape

of the blades towards the point. The handle of the tint-tool is of the

same form as that of a graver. The figure marked A presents a side view

of the blade; the others marked B show the faces. Some engravers never

use a tint-tool, but cut all their lines with a graver. There is,

however, great uncertainty in cutting a series of parallel lines in this

manner, as the least inclination of the hand to one side will cause the

graver to increase the width of the white line cut out, and

undercut the raised one left, more than if in the same

circumstances a tint-tool were used. This will be rendered more evident

by a comparison of the points and faces of the two different tools: The

tint-tool, being very little thicker at B than at the point A, will

cause a very trifling difference in the width of a line in the event of

a wrong inclination, when compared with the inequality occasioned by the

unsteady direction of a graver, whose angle at the point is much greater

than that of a proper tint-tool. Tint-tools ought to be sufficiently

strong at the back to prevent their bending in the middle of the blade

when used, for with a weak tool of this kind the engraver cannot

properly guide the point, and hence freedom of execution is lost.

Tint-tools that are rather thick in the back are to be preferred to such

as are thin, not only from their allowing of great steadiness in

cutting, but from their leaving the raised lines thicker at the bottom,

and consequently more capable of sustaining the action of the press.

A tint-tool that is of the same thickness, both at the back and the

lower part, cuts out

578

the lines in such manner that a section of them appears thus:

![]() the black or raised lines from which the impression is obtained being no

thicker at their base than at the surface; while a section of the lines

cut by a tool that is thicker at the back than at the lower part appears

thus.

the black or raised lines from which the impression is obtained being no

thicker at their base than at the surface; while a section of the lines

cut by a tool that is thicker at the back than at the lower part appears

thus.

![]() It is evident that lines of this kind, having a better support at the

base, are much less liable than the former to be broken in printing.

It is evident that lines of this kind, having a better support at the

base, are much less liable than the former to be broken in printing.

GOUGES.

![]()

CHISELS.

![]()

C

Gouges of different sizes, from A the smallest to B the largest, as here represented, are used for scooping out the wood towards the centre of the block; while flat tools or chisels, of various sizes, are chiefly employed in cutting away the wood towards the edges. Flat tools of the shape seen in figure C are sometimes offered for sale by tool-makers, but they ought never to be used; for the projecting corners are very apt to cut under a line, and thus remove it entirely, causing great trouble to replace it by inserting new pieces of wood.

The face of both gravers and tint-tools ought to be kept rather long

than short; though if the point be ground too fine, it will be

very liable to break. When the face is long—or, strictly speaking,

when the angle, formed by the plane of the face and the lower line of

the blade, is comparatively acute—thus,

![]() a line is cut with much greater clearness than when the face is

comparatively obtuse, and the small shaving cut out turns gently over

towards the hand. When, however, the face of the tool approaches to the

shape seen in the following cut, the reverse happens; the small shaving

is rather ploughed out than cleanly cut out; and the force necessary to

push the tool forward frequently causes small pieces to fly out at each

side of the hollowed line, more especially if the wood be dry. The

shaving also, instead of turning aside over the face of the tool, turns

over before the point, thus,

a line is cut with much greater clearness than when the face is

comparatively obtuse, and the small shaving cut out turns gently over

towards the hand. When, however, the face of the tool approaches to the

shape seen in the following cut, the reverse happens; the small shaving

is rather ploughed out than cleanly cut out; and the force necessary to

push the tool forward frequently causes small pieces to fly out at each

side of the hollowed line, more especially if the wood be dry. The

shaving also, instead of turning aside over the face of the tool, turns

over before the point, thus,

![]() and hinders the engraver from seeing that part of the pencilled line

which is directly under it. A short-faced tool of itself prevents

the engraver from distinctly seeing the point. When the face of a tool

has become obtuse, it ought to be ground to a proper form, for instance,

from the shape of the figure A to that of B.

and hinders the engraver from seeing that part of the pencilled line

which is directly under it. A short-faced tool of itself prevents

the engraver from distinctly seeing the point. When the face of a tool

has become obtuse, it ought to be ground to a proper form, for instance,

from the shape of the figure A to that of B.

![]()

![]()

Gravers and tint-tools when first received from the maker are generally too hard,—a defect which is soon discovered by the point breaking off short as soon as it enters the wood. To remedy this, the blade of the tool ought to be placed with its flat side above a piece of iron—a poker will do very well—nearly red-hot. Directly it changes to a straw colour it is to be taken off the iron, and either dipped in sweet oil or allowed to cool gradually. If removed from the iron while it is still of a straw colour, it will have been softened no more than sufficient; but should it have acquired a purple tinge, it will have been softened too much; and instead of breaking at the point, as before, it will bend. A small grindstone is of great service in grinding down the faces of tools that have become obtuse. A Turkey stone, though the operation requires more time, is however a very good substitute, as, besides reducing the face, the tool receives a point at the same time. Though some engravers use only a Turkey stone for sharpening their tools, yet a hone in addition is of great advantage. A graver that has received a final polish on a hone cuts a clearer line than one which has only been sharpened on a Turkey stone; it also cuts more pleasantly, gliding smoothly through the wood, if it be of good quality, without stirring a particle on each side of the line.

![]()

The gravers and tint-tools used for engraving on a plane surface are straight at the point, as is here represented; but for engraving on a block rendered concave in certain parts by lowering, it is necessary that the point should have a slight inclination upwards, thus. The dotted lines show the direction of the point used for plane surface engraving. There is no difficulty in getting a tool to descend on one side of a part hollowed out or lowered; but unless the point be slightly inclined upwards, as is here shown, it is extremely difficult to make it ascend on the side opposite, without getting too much hold, and thus producing a wider white line than was intended.

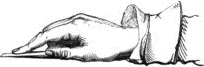

As the proper manner of holding the graver is one of the first things that a young wood engraver is taught, it is necessary to say a few words on this subject. Engravers on copper and steel, who have much harder substances than wood to cut, hold the graver with the fore-finger extending on the blade beyond the thumb, thus, so that by its pressure the point may be pressed into the plate. As box-wood, however, is much softer than copper or steel, and as it is seldom of perfectly equal hardness 580 throughout, it is necessary to hold the graver in a different manner, and employ the thumb at once as a stay or rest for the blade, and as a check upon the force exerted by the palm of the hand, the motion being chiefly directed by the fore-finger, as is shown in the following cut.

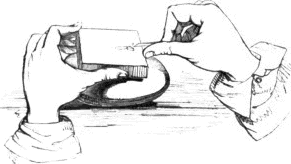

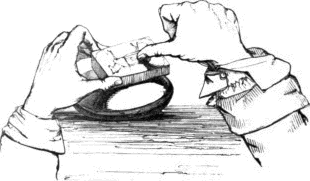

The thumb, with the end resting against the side of the block, in the manner above represented, allows the blade to move back and forward with a slight degree of pressure against it, and in case of a slip it is ever ready to check the graver’s progress. This mode of resting the thumb against the edge of the block is, however, only applicable when the cuts are so small as to allow of the graver, when thus guided and controlled, to reach every part of the subject. When the cut is too large to admit of this, the thumb then rests upon the surface of the block, thus:

still forming a stay to the blade of the graver, and a check to its slips, as before.

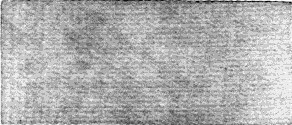

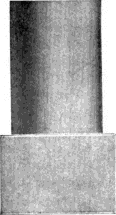

581In order to acquire steadiness of hand, the best thing for a pupil to begin with is the cutting of tints,—that is, parallel lines; and the first attempts ought to be made on a small block such as is represented in No. 1, which will allow each entire line to be cut with the thumb resting against the edge. When lines of this length can be cut with tolerable precision, the pupil should proceed to blocks of the size of No. 2. He ought also to cut waved tints, which are not so difficult; beginning, as in straight ones, with a small block, and gradually proceeding to blocks of greater size. Should the wood not cut smoothly in the direction in which he has begun, he should reverse the block, and cut his lines in the opposite direction; for it not unfrequently happens that wood which cuts short and crumbles in one direction will cut clean and smooth the opposite way. It is here necessary to observe, that if a certain number of lines be cut in one direction, and another portion, by reversing the block, be cut the contrary way, the tint, although the same tool may have been used for all, will be of two different shades, notwithstanding the pains that may have been taken to keep the lines of an even thickness throughout. This difference in the appearance of the two portions of lines cut from opposite sides is entirely owing to the wood cutting more smoothly in one direction than another, although the difference in the resistance which it makes to the tool may not be perceptible by the hand of the engraver. It is of great importance that a pupil should be able to cut tints well before he proceeds to any other kind of work. The practice will give him steadiness of hand, and he will thus acquire a habit of carefully executing such lines, which subsequently will be of the greatest service. Wood engravers who have not been well schooled in this elementary part of their profession often cut their tints carelessly in the first instance, and, when they perceive the defect in a proof, return to their work; and, with great loss of time, keep thinning and dressing the lines, till they frequently make the tint appear worse than at first.

No. 2.

582When uniform tints, both of straight and waved lines, can be cut with facility, the learner should proceed to cut tints in which the lines are of unequal distance apart. To effect this, tools of different sizes are necessary; for in tints of this kind the different distances between the black lines, are according to the width of the different tools used to cut them; though in tints of a graduated tone of colour, the difference is sometimes entirely produced by increasing the pressure of the graver. In the annexed cut, No. 3, the black lines are of equal thickness, but the width of the white lines between them becomes gradually less from the top to the bottom. By comparing it with No. 4, the difference between a uniform tint, where the lines are of the same thickness and equally distant, and one where the distance between the lines is unequal, will be more readily understood.

A straight-line tint, either uniform, or with the lines becoming gradually closer without appearing darker, is generally adopted to represent a clear blue sky. In No. 3 the tint has been commenced with a comparatively broad-pointed tool; and after cutting a few lines, less pressure, thus allowing the black lines to come a little closer together, has been used, till it became necessary to change the tool for one less broad in the face. In this manner a succession of tools, each finer than the preceding, has been employed till the tint was completed.—To be able to produce a tint of delicately graduated tone, it is necessary that the engraver should be well acquainted with the use of his tools, and also have a correct eye. The following is a specimen of a tint cut entirely with the same graver, the difference in the colour being produced by increasing the pressure in the lighter parts.

Tints of this kind are obtained with greater facility and certainty by using a graver, and 583 increasing the pressure, than by using several tint-tools. On comparing No. 3 with No. 5, it will be perceived that the black lines in the latter decrease in thickness as they approach the bottom of the cut, while in the former they are of a uniform thickness throughout. If a clear sky is to be represented, there is no other mode of making that part near the horizon appear to recede except by means of fine black lines becoming gradually closer as they descend, as seen in the tint No. 3. As the black lines in this tint are closer at the bottom than at the top, it might naturally be supposed that the colour would be proportionably stronger in that part. It is, however, known by experience that the unequal distance of the lines in such a tint does not cause any perceptible difference in the colour; as the upper lines, in consequence of their being more apart, print thicker, and thus counterbalance the effect of the greater closeness of the others.

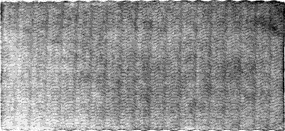

The two following cuts are specimens of tints represented by means of waved lines: in No. 6 the lines are slightly undulated; in No. 7 they have more of the appearance of zig-zag.

No. 6.

No. 7.

Waved lines are generally introduced to represent clouds, as they not only form a contrast with the straight lines of the sky, but from their form suggest the idea of motion. It is necessary to observe, that if the alternate undulations in such lines be too much curved, the tint, 584 when printed, will appear as if intersected from top to bottom, like wicker-work with perpendicular stakes, in the manner shown in the following specimen, No. 8. This appearance is caused by the unequal pressure of the tool in forming the small curves of which each line is composed, thus making the black or raised line rather thicker in some parts than in others, and the white interstices wide or narrow in the same proportion. The appearance of such a tint is precisely the same whether cut by hand or by a machine.IX.15 In executing waved tints it is therefore necessary to be particularly careful not to get the undulations too much curved.

No. 8.

As the choice of proper tints depends on taste, no specific rules can be laid down to guide a person in their selection. The proper use of lines of various kinds as applied to the execution of wood-cuts, is a most important consideration to the engraver, as upon their proper application all indications of form, texture, and conventional colour entirely depend. Lines are not to be introduced merely as such,—to display the mechanical skill of the engraver; they ought to be the signs of an artistic meaning, and be judged of accordingly as they serve to express it with feeling and correctness. Some wood engravers are but too apt to pride themselves on the delicacy of their lining, without considering whether it be well adapted to express their subject; and to fancy that excellence in the art consists chiefly in cutting with great labour a number of delicate unmeaning lines. To such an extent is this carried by some of this class that they spend more time in expressing the mere scratches of the designer’s pencil in a shade than a Bewick or a Clennell would require to engrave a cut full of meaning and interest. Mere delicacy of lines will not, however, compensate for want of natural 585 expression, nor laborious trifling for that vigorous execution which is the result of feeling. “Expression,” says Flaxman, “engages the attention, and excites an interest which compensates for a multitude of defects—whilst the most admirable execution, without a just and lively expression, will be disregarded as laborious inanity, or contemned as an illusory endeavour to impose on the feelings and the understanding.—Sentiment gives a sterling value, an irresistible charm, to the rudest imagery or the most unpractised scrawl. By this quality a firm alliance is formed with the affections in all works of art.”IX.16 Perpetrators of laborious inanities find, however, their admirers; and an amateur of such delicacies is in raptures with a specimen of “exquisitely fine lining,” and when told that such wood-peckings are, as works of art, much inferior to the productions of Bewick, he asks where his works are to be found; and after he has examined them he pronounces them “coarse and tasteless,—the rude efforts of a country engraver,” and not to be compared with certain delicate, but spiritless, wood engravings of the present day.

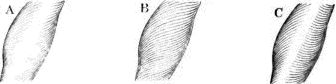

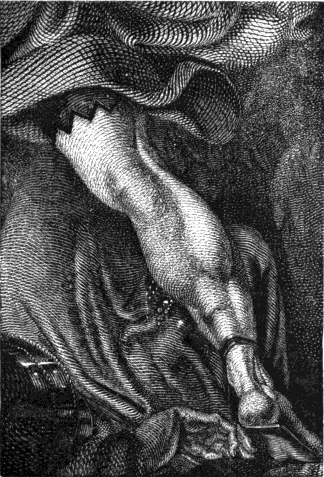

With respect to the direction of lines, it ought at all times to be borne in mind by the wood engraver,—and more especially when the lines are not laid in by the designer,—that they should be disposed so as to denote the peculiar form of the object they are intended to represent. For instance, in the limb of a figure they ought not to run horizontally or vertically,—conveying the idea of either a flat surface or of a hard cylindrical form,—but with a gentle curvature suitable to the shape and the degree of rotundity required. A well chosen line makes a great difference in properly representing an object, when compared with one less appropriate, though more delicate. The proper disposition of lines will not only express the form required, but also produce more colour as they approach each other in approximating curves, as in the following example, and thus represent a variety of light and shade, without the necessity of introducing other lines crossing them, which ought always to be avoided in small subjects: if, however, the figures be large, it is necessary to break the hard appearance of a series of such single lines by crossing them with others more delicate.

In cutting curved lines, considerable difficulty is experienced by not commencing properly. For instance, if in executing a series of such lines as are shown in the preceding cut, the engraver commences at A, and works towards B, the tool will always be apt to cut through the black line already formed; whereas by commencing at B, and working towards A, the graver is always outside of the curve, and consequently 586 never touches the lines previously cut.IX.17 This difference ought always to be borne in mind when engraving a series of curved lines, as, by commencing properly, the work is executed with greater freedom and ease, while the inconvenience arising from slips is avoided. When such lines are introduced to represent the rotundity of a limb, with a break of white in the middle expressive of its greatest prominence, as is shown in the following figure A, it is advisable that they should be first laid in as if intended to be continuous, as is seen in figure B, and the part which appears white in A lowered out before beginning to cut them, as by this means all risk of their disagreeing, as in C, will be avoided.

The rotundity of a column or similar object is represented by means of parallel lines, which are comparatively open in the middle where light is required, but which are engraved closer and thicker towards the sides to express shade. The effect of such lines will be rendered more evident by comparing the column in the annexed cut with the square base, which is represented by a series of equidistant lines, each of the same thickness as those in the middle of the column.

Many more examples of tints and simple lines might be given; but, as no real benefit would be derived from them, it is needless to increase the number, and make “much ado about nothing.” Every new subject that the engraver commences presents something new for him to effect, and requires the exercise of his taste and judgment as to the best mode of executing it, so that the whole may have some claim to the character of a work of art. If a thousand examples were given, they would not enable an engraver to 587 execute a subject properly, unless he were endowed with that indefinable feeling which at once suggests the best means of attaining his end. Such feeling may indeed be excited, but can never be perfectly communicated by rules and examples. In this respect every artist, whether a humble wood engraver, or a sculptor or a painter of the highest class, must be self-instructed; the feeling displayed in his works must be the result of his own perceptions and ideas of beauty and propriety. It is the difference in feeling, rather than any greater or less degree of excellence in the mechanical execution, that distinguishes the paintings of Raffaele from those of Le Brun, Flaxman’s statues from those of Roubilliac, and the cuts in the Lyons Dance of Death from many of the laborious inanities of the present day.

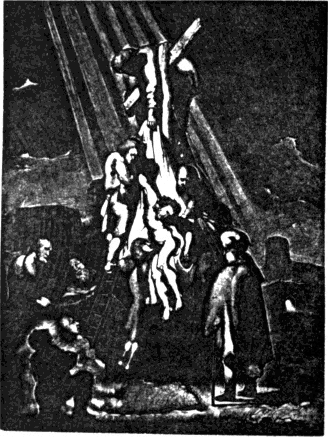

Clear, unruffled water, and all bright and smooth metallic substances, are best represented by single lines; for if cross-lines be introduced, except to indicate a strong shadow, it gives to them the appearance of roughness, which is not at all in accordance with the ideas which such substances naturally excite. Objects which appear to reflect brilliant flashes of light ought to be carefully dealt with, leaving plenty of black as a ground-work, for in wood engravings such lights can only be effectively represented by contrast with deep colour. Reflected lights are in general best represented by means of single lines running in the direction of the object, with a few touches of white judiciously taken out. In this respect Clennell particularly excelled as a wood engraver. Painting itself can scarcely represent reflected lights with greater effect than he has expressed them in several of his cuts. In Harvey’s large cut of the Death of Dentatus, after Haydon’s noble picture, the shield of Dentatus affords an instance of reflected light most admirably represented.

As my object is to point out to the uninitiated the method of cutting certain lines, rather than to engage in the fruitless task of showing how such lines are to be generally applied, I shall now proceed to offer a few observations on engraving in outline, a process with which the learner ought to be well acquainted before he attempts subjects consisting of complicated lines. The word outline in wood engraving has two meanings: it is used, first, to denote the distinct boundaries of all kinds of objects; and secondly, to denote the delicate white line that is cut round any figure or object in order to form a boundary to the lines by which such figure or object is surrounded, and to thus allow of their easier liberation: it forms as it were a terminal furrow into which the lines surrounding the figure run. In speaking of this second outline in future, it will be distinguished as the white outline; while the other, which properly defines the different figures and forms, will be called the true or proper outline, or simply 588 the outline, without any distinctive additional term. As the white outline ought never to be distinctly visible in an impression, care ought to be taken, more especially where the adjacent tint is dark, not to cut it too deep or too wide. In the first of the two following cuts, the white outline, intentionally cut rather wider than is necessary, is distinctly seen from its contrast with the dark parts immediately in contact with it.

In the second cut of the same subject, with a different back-ground, it is less visible in consequence of the parts adjacent being light. It is, however, still distinctly seen in the shadow of the feet; but it is shown here purposely to point out an error which is sometimes committed by cutting a white outline where, as in these parts, it is not required. The white outline is here quite unnecessary, as the two blacks 589 ought not to be separated in such a manner; the proper intention of the white outline is not so much to define the form of the figure or object, but, as has been already explained, to make an incision in the wood as a boundary to other lines coming against it, and to allow of their being clearly liberated without injury to the proper outline of the object: when a line is cut to such a boundary, the small shaving forced out by the graver becomes immediately released, without the point of the tool coming in contact with the true outline. The old German wood engravers, who chiefly engraved large subjects on apple or pear tree, and on the side of the wood, were not in the habit of cutting a white outline round their figures before they began to engrave them, and hence in their cuts objects frequently appear to stick to each other. The practice is now, however, so general, that in many modern wood-cuts a white line is improperly seen surrounding every figure.

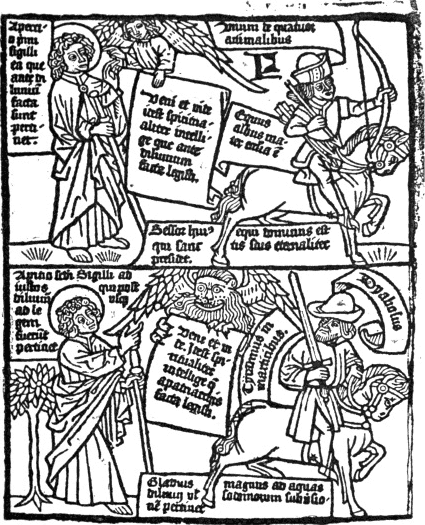

In proceeding to engrave figures, it is advisable to commence with such as consist of little more than outline, and have no shades expressed by cross-lines. The first step in executing such a subject is to cut a white line on each side of the pencilled lines which are to remain in relief of the height of the plane surface of the block, and to form the impression when it is printed. A cut when thus engraved, and previous to the parts which are white, when printed, being cut away, or, in technical language, blocked out, would present the following appearance.IX.18

It is, however, necessary to observe that all the parts which require to be blocked away have been purposely retained in this cut in order to show more clearly the manner in which it is executed; for the engraver usually cuts away as he proceeds all the black masses seen within the subject. A wide margin of solid wood round the edges of the cut is, 590 however, generally allowed to remain until a proof be taken when the engraving is finished, as it affords a support to the paper, and prevents the exterior lines of the subject from appearing too hard. This margin, where room is allowed, is separated from the engraved parts by a moderately deep and wide furrow, and is covered with a piece of paper serving as a frisket in taking a proof impression by means of friction. In clearing away such of the black parts in the preceding cut as require to be removed, it is necessary to proceed with great care in order to avoid breaking down or cutting through the lines which are to be left in relief. When the cut is properly cleared out and blocked away, it is then finished, and when printed will appear thus:

Sculptures and bas-reliefs of any kind are generally best represented by simple outlines, with delicate parallel lines, running horizontally, to represent the ground. The following cut is from a design by Flaxman for the front of a gold snuff-box made by Rundell and Bridge for George IV. about 1827.

The subject of this design was intended to commemorate the General Peace concluded in 1814: to the left Agriculture is seen flourishing under the auspices of Peace; while to the right a youthful figure is seen placing a wreath above the helmet of a warrior; the trophy indicates his services, and opposite to him is seated a figure of Victory. The three other sides, and the top and bottom, were also 591 embellished with figures and ornaments in relief designed by Flaxman. The whole of the dies were cut in steel by Henning and Son—so well known to admirers of art from their beautiful reduced copies and restorations of the sculptures of the Parthenon preserved in the British Museum—and from these dies the plates of gold composing the box were struck, so that the figures appear in slight relief. A blank space was left in the top of the box for an enamel portrait of the King, which was afterwards inserted, surrounded with diamonds, and the margin of the lid was also ornamented in the same manner. This box is perhaps the most beautiful of the kind ever executed in any country: it may justly challenge a comparison with the drinking cups by Benvenuto Cellini, the dagger hafts designed by Durer, or the salts by Hans Holbein. The process of engraving in this style is extremely simple, as it is only necessary to leave the lines drawn in pencil untouched, and to cut away the wood on each side of them. An amateur may without much trouble teach himself to execute cuts in this manner, or to engrave fac-similes of small pen-and-ink sketches such as the annexed.IX.19

Having now explained the mode of procedure in outline engraving, it seems necessary, before proceeding to speak of more complicated subjects, to say a few words respecting drawings made on the block; for, however well the engraving may be executed, the cut which is a fac-simile of a bad drawing can never be a good one. An artist’s knowledge of drawing is put to the test when he begins to make designs on wood; he cannot resort, as in painting, to the trick of colour to conceal the defects of his outlines. To be efficient in the engraving, his principal figures must be distinctly made out; a drawing on the wood admits of no scumbling; black and white are the only means by which the subject can be represented; and if he be ignorant of the proper management of chiaro-scuro, and incorrect and feeble in his drawing, he will not be able 592 to produce a really good design for the wood engraver. Many persons can paint a tolerably good picture who are utterly incapable of making a passable drawing on wood. Their drawing will not stand the test of simple black and white; they can indicate generalities “indifferently well” by means of positive colours, but they cannot delineate individual forms correctly with the black-lead pencil. It is from this cause that we have so very few persons who professedly make designs for wood engravers; and hence the sameness of character that is to be found in so many modern wood-cuts. It is not unusual for many second and third rate painters, when applied to for a drawing for a wood-cut, to speak slightingly of the art, and to decline to furnish the design required. This generally results rather from a consciousness of their own incapacity than from any real contempt for the art. As greater painters than any now living have made designs for wood engravers in former times, a second or third rate painter of the present day surely could not be much degraded by doing the same. The true reason for the refusal, however, is generally to be found in such painter’s incapacity.

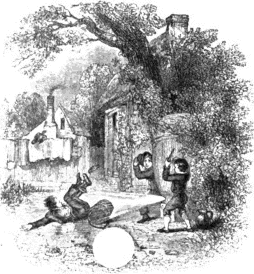

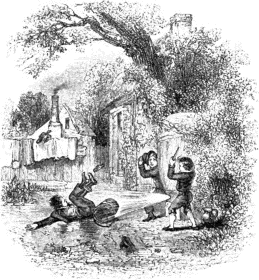

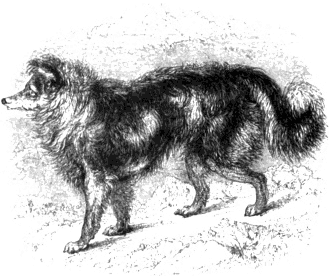

The two next cuts, both drawn from the same sketch,IX.20 but by different persons, will show how much depends upon having a good, artist-like drawing. The first is meagre; the second, on the contrary, is remarkably spirited, and the additional lines which are introduced not only give effect to the figure, but also in printing form a support to the more delicate parts of the outline.

593Though a learner in proceeding from one subject to another more complicated will doubtless meet with difficulties which may occasionally damp his ardour, yet he will encounter none which will not yield to earnest perseverance. As it is not likely that any amateur practising the art merely for amusement would be inclined to test his patience by proceeding beyond outline engraving, the succeeding remarks are more especially addressed to those who may wish to apply themselves to wood engraving as a profession.

When beginning to engrave in outline, it is advisable that the subjects first attempted should be of the most simple kind,—similar, for instance, to the preceding figure marked No. 1. When facility in executing cuts in this style is obtained, the learner may proceed to engrave such as are slightly shaded, and have a back-ground indicated as in No. 2. He may next proceed to subjects containing a greater variety of lines, and requiring greater neatness of execution, but should by no means endeavour to get on too fast by attempting to do much before he can do a little well. Whatever kind of subject be chosen, particular attention ought to be paid to the causes of failure and success in the execution. By diligently noting what produces a good effect in certain subjects, he will, under similar circumstances, be prepared to apply the same means; and by attending to the faults in his work he will be the more careful to avoid them in future. The group of figures here, selected from Sir David Wilkie’s picture of the Rent Day, will serve as an example of a cut executed by comparatively simple means; the subject is also 594 such a one as a pupil may attempt after he has made some progress in engraving slightly shaded figures. There are no complicated lines which are difficult to execute; the hatchings are few, and of simple character; and for the execution of the whole, as here represented, nothing is required but a feeling for the subject; and a moderate degree of skill in the use of the graver, combined with patient application.

When the pupil is thus far advanced, he ought, in subjects of this kind, to avoid introducing more work, more especially in the features, than he can execute with comparative facility and precision; for, by attempting to attain excellence before he has arrived at mediocrity, he will be very likely to fail, and instead of having reason to congratulate himself on his success, experience nothing but disappointment. To make wood engraving an interesting, instead of an irksome study to young persons, I would recommend for their practice not only such subjects as are likely to engage their attention, but also such as they may be able to finish before they become weary of their task. At this period every endeavour ought to be made to smooth the pupil’s way by giving him such subjects to execute as will rather serve to stimulate his exertions than exhaust his patience. Little characteristic figures, like the one here copied, from one of Hogarth’s plates of the Four Parts of the Day, seem most suitable for this purpose. A subject of this kind does not contain so much work as to render a young person tired of it before 595 it be finished; while at the same time it serves to exercise him in the practice of the art and to engage his attention.

When a pupil feels no interest in what he is employed on, he will seldom execute his work well; and when he is kept too long in engraving subjects that merely try his patience, he is apt to lose all taste for the art, and become a mere mechanical cutter of lines, without caring for what they express.

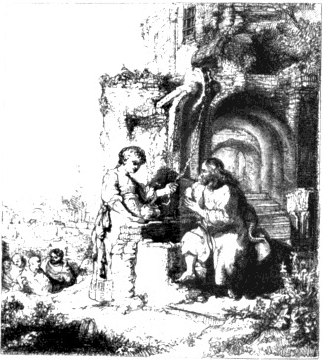

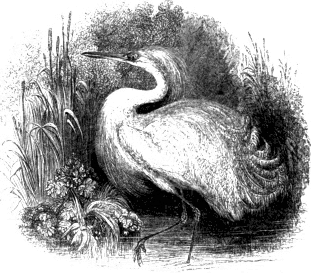

Such a cut as the following—copied from an etching by Rembrandt—will form a useful exercise to the pupil, after he has attained facility in the execution of outline subjects, while at the same time it will serve to display the excellent effect in wood engravings of well contrasted light and shade. The hog—which is here the principal object—immediately arrests the eye, while the figures in the back-ground, being introduced merely to aid the composition and form a medium between the dark colour of the animal and the white paper, consist of little more than outline, and are comparatively light. In engraving the hog, it is necessary to exercise a little judgment in representing the bristly hair, and in touching the details effectively.

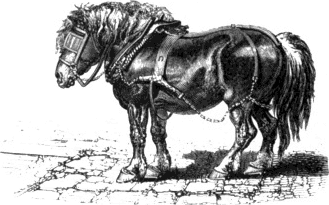

When a learner has made some progress, he may attempt such a cut as that on the next page in order to exercise himself in the appropriate representation of animal texture. The subject is a dray-horse, formerly belonging to Messrs. Meux and Co., and the drawing was made on the block by James Ward, R.A., one of the most distinguished animal painters of the present time. Such a cut, though executed by simple 596 means, affords an excellent test of a learner’s skill and discrimination: the hide is smooth and glossy; the mane is thick and tangled; the long flowing hair of the tail has to be represented in a proper manner; and the markings of the joints require the exercise of both judgment and skill. By attending to such distinctions at the commencement of his career, he will find less difficulty in representing objects by appropriate texture when he shall have made greater progress, and will not be entirely dependent on a designer to lay in for him every line. An engraver who requires every line to be drawn, and who is only capable of executing a fac-simile of a design made for him on the block, can never excel.

As enough perhaps has been said in explanation of the manner of cutting tints, and of figures chiefly represented by single lines, I shall now give a cut—Jacob blessing the children of Joseph—in which single-lined figures and tint are combined. It is necessary to observe that this cut is not introduced as a good specimen of engraving, but as being well adapted, from the simplicity of its execution, to illustrate what I have to say. The figures are represented by single lines, which require the exercise of no great degree of skill; and by the introduction of a varied tint as a back-ground the cut appears like a complete subject, and not like a sketch, or a detached group.

It is necessary to remark here, that when comparatively light objects, such as the figures here seen, are to be relieved by a tint of any kind, whether darker or lighter, such objects are now generally separated from it by a black outline. The reason for leaving such an outline in parts where the conjunction of the tint and the figures does not render it absolutely necessary is this: as those parts in a cut which appear white 597 in the impression are to be cut away—as has already been explained,—it frequently happens that when they are cut away first, and the tint cut afterwards, the wood breaks away near the termination of the line before the tool arrives at the blank or white. It is, therefore, extremely difficult to preserve a distinct outline in this manner, and hence a black conventional outline is introduced in those parts where properly there ought to be none, except such as is formed by the tint relieving against the white parts, as is seen in the back part of the head of Jacob in the present cut, where there is no other outline than that which is formed by the tint relieving against his white cap. Bewick used to execute all his subjects in this manner; but he not unfrequently carried this principle too far, not only running the lines of his tints into the white on the light side of his figures,—that is, on the side on which the light falls,—but also on both sides of a light object.

Before dismissing this part of the subject, it is necessary to observe further, that when the white parts are cut away before the tint is introduced, the conventional black outline is very liable to be cut through by the tool slipping. This will be rendered more intelligible by an inspection of the following cut,IX.21 where the house is seen finished, 598 and the part where a tint is intended to be subsequently engraved appears black. Any person in the least acquainted with the practice of wood engraving, will perceive, that should the tool happen to slip when near the finished parts, in coming directly towards them, it will be very likely to cut the outline through, and to make a breach in proportion as such outline may be thin, and thus yield more readily to the force of the tool.