he

best of the wood-cuts of the time of Albert Durer, more especially those

executed by German engravers, are for the most part of rather large

size; the best of those, however, which appeared within forty years of

his decease are generally small. The art of wood engraving, both as

regards design and execution, appears to have attained its highest

perfection within about ten years of the time of Durer’s decease; for

the cuts which, in my opinion, display the greatest excellence of the

art as practised in former times, were published in 1538. The cuts to

which I allude are those of the celebrated Dance of Death, which were

first published in that year at Lyons. So admirably are those cuts

executed,—with so much feeling and with so perfect a knowledge of

the capabilities of the art,—that I do not think any wood engraver

of the present time is capable of surpassing them. The manner in which

they are engraved is comparatively simple: there is no laboured and

unnecessary cross-hatching where the same effect might be obtained by

simpler means; no display

325

of fine work merely to show the artist’s talent in cutting delicate

lines. Every line is expressive; and the end is always obtained by the

simplest means. In this the talent and feeling of the engraver are

chiefly displayed. He wastes not his time in mere mechanical

execution—which in the present day is often mistaken for

excellence;—he endeavours to give to each character its

appropriate expression; and in this he appears to have succeeded better,

considering the small size of the cuts, than any other wood engraver,

either of times past or present.

he

best of the wood-cuts of the time of Albert Durer, more especially those

executed by German engravers, are for the most part of rather large

size; the best of those, however, which appeared within forty years of

his decease are generally small. The art of wood engraving, both as

regards design and execution, appears to have attained its highest

perfection within about ten years of the time of Durer’s decease; for

the cuts which, in my opinion, display the greatest excellence of the

art as practised in former times, were published in 1538. The cuts to

which I allude are those of the celebrated Dance of Death, which were

first published in that year at Lyons. So admirably are those cuts

executed,—with so much feeling and with so perfect a knowledge of

the capabilities of the art,—that I do not think any wood engraver

of the present time is capable of surpassing them. The manner in which

they are engraved is comparatively simple: there is no laboured and

unnecessary cross-hatching where the same effect might be obtained by

simpler means; no display

325

of fine work merely to show the artist’s talent in cutting delicate

lines. Every line is expressive; and the end is always obtained by the

simplest means. In this the talent and feeling of the engraver are

chiefly displayed. He wastes not his time in mere mechanical

execution—which in the present day is often mistaken for

excellence;—he endeavours to give to each character its

appropriate expression; and in this he appears to have succeeded better,

considering the small size of the cuts, than any other wood engraver,

either of times past or present.

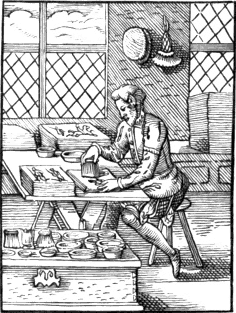

Though two or three of the cuts which will subsequently be given may be of rather earlier date than those of the Dance of Death, it seems preferable to give first some account of this celebrated work; and to introduce the cuts alluded to, though not in strict chronological order,—which is the less necessary as they do not illustrate the progress of the art,—with others executed in a similar style.

Long before the publication of the work now so generally known as “The Dance of Death,” a series of paintings representing, in a similar manner, Death seizing on persons of all ranks and ages, had appeared on the walls of several churches. A Dance of Death was painted in the cloisters of the Church of the Innocents at Paris, in the cloisters of St. Paul’s, London, and in the portico of St. Mary’s, Lubec. The painting in St Paul’s is said to have been executed at the cost of one Jenkin Carpenter, who lived in the reign of Henry VI, and who was one of the executors of that famous “lord-mayor of London,” Richard Whittington; and Dugdale, in his History of St. Paul’s Cathedral, says that it was in imitation of that in the cloisters of the Church of the Innocents at Paris.VI.1 This subject seems to have been usually known in former times by the name of “The Dance of Machabre,” from a French or German poet—for this point is not settled by the learned—of the name of Macaber or Macabre, who is said to have written a poem on this subject.VI.2 The 326 Dance of Death, however, which as a painting has attained greater celebrity and given rise to much more discussion than any other, is that which was painted on the wall of a kind of court-house attached to the Church of the Dominicans at Basle. This painting has frequently been ascribed to Holbein; but it certainly was executed before he was born; and there is not the slightest reason to believe that he ever touched it in any of the repairs which it underwent in subsequent years.

The following particulars respecting this painting are such as seem best authenticated.

It is said to owe its origin to a plague which ravaged the city of Basle in 1439, during the time of the great council, which commenced in 1431, and did not terminate till 1448. A number of persons of almost all ranks, whom the council had brought to this city, having fallen victims to the plague, it is said that the painting was executed in remembrance of the event, and as a memento of the uncertainty of life. Though it may be true that the great mortality at Basle in 1439 might have been the occasion of such a picture in the church-court—Kirchhofe, as it is called by Hegner in his Life of Holbein—of the Dominicans in that city, it is almost certain that the subject must have been suggested by one of much earlier date painted on the walls of an old building which had formerly been the cloisters of a nunnery which stood in that part of Basle which is called the Little City. This convent was founded in 1275; and the painting appears to have been executed in 1312, according to the following date, which was to be seen above one of the figures, that of the Count, who was also one of the characters in the painting in the church-court of the Dominicans: “Dussent jar treihuntert und Xii;” in English: One thousand three hundred and twelve. Several of the figures in this old painting were almost the same as in that of the church-court of the Dominicans, though executed in a coarser manner; and, like the latter, were accompanied with explanatory inscriptions in verse. This curious old work appears to have remained unnoticed till 1766, when one Emanuel Büchel, of Basle, by trade a baker, but an admirer of art, and an industrious draughtsman, had his attention directed to it. He made a careful copy in colours of all that then remained of it, and his drawings are now in the public library of Basle. 327 “This oldest Dance of Death,” says Hegner, writing in 1827, “is almost entirely effaced, and becomes daily more so, as well on account of age as from the cloisters of the old nunnery having been for many years used as a warehouse for salt.”VI.3

It is supposed that the Dance of Death in the church-court of the Dominicans at Basle was originally painted in fresco or distemper. The number of characters, each accompanied by a figure of Death, was originally forty;VI.4 but in 1568, a painter, named Hans Hugo Klauber, who was employed by the magistrates to repair the old painting, introduced a figure of the reformer Oecolampadius as if preaching to the characters composing the Dance, with portraits of himself, his wife, and their little son, at the end. It is probable that he painted over the old figures in oil-colour, and introduced sundry alterations, suggested by other paintings and engravings of the same subject. It appears likely that, at the same time, many of the old inscriptions were changed for others more in accordance with the doctrines of the Reformation, which then prevailed at Basle. The verses above the figure of the Pope were certainly not such as would have been tolerated at the period when the subject is supposed to have been first painted.VI.5 In 1616 the painting was again repaired; but, though a Latin inscription was then added containing the names of the magistrates who had thus taken care to preserve it, there is no mention made of any artist by whom the subject 328 had been originally painted or subsequently retouched. Had there been any record of Holbein having been at any time employed on the work, such a circumstance would most likely have been noticed; as his memory was then held in the highest estimation, and Basle prided herself on having had so eminent an artist enrolled among the number of her citizens. In 1658 the painting was again renewed: and there seems reason to believe that further alterations were then introduced both in the costume and the colouring. It was retouched in 1703; but from that time, as the paint began to peel off from the decaying walls, all attempts for its further preservation appear to have been considered hopeless. It would indeed seem to have become in a great measure disregarded by the magistrates, for a rope-maker used to exercise his trade under the roof that protected it from the weather. As the old wall stood much in the way of new buildings, it is not unlikely that they might be rather wishful to have it removed. In 1805 the magistrates pronounced sentence against the Dance of Death, and the wall on which it was painted was by their orders pulled down, though not without considerable opposition on the part of many of the citizens, more especially those of the suburb of St. John, within which the old church-court of the Dominicans stood. Several pieces of the painting were collected, and are still preserved at Basle as memorials of the old “Todten-tanz,” which was formerly an object of curiosity with all strangers who visited the city, and which has been so frequently the subject of discussion in the history of art.

Mr. Douce has given a list of many books containing the figures of a Dance of Death printed before the celebrated Simulachres et Historiées Faces de la Mort of Lyons, 1538; and among the principal the following may be here enumerated.—A German edition, intitled “Der Dodtendanz mit figuren. Clage und Antwort schon von allen staten der Welt.” This work, which is small folio, is mentioned in Braun’s Notitia librorum in Bibliotheca ad SS. Udalricum et Afram Augustæ, vol. ii. p. 62. It is without date, but Braun supposes that it may have been printed between 1480 and 1500. It consists of twenty-two leaves, with wood-cuts of the Pope, Cardinal, Bishop, Abbot, &c. &c. accompanied by figures of Death. The descriptions are in German verse, and printed in double columns.—The earliest printed book on this subject with a date is intitled “La Danse Macabre imprimée par ung nommé Guy Marchand,” &c. Paris, 1485, small folio. In 1486 Guy Marchand,—or Guyot Marchant, as he is also called,—printed another edition, “La Danse Macabre nouvelle,” with several additional cuts; and in the same year he printed “La Danse Macabre des Femmes,” a small folio of fifteen leaves. This is the first edition of the Macaber Dance of females. Thirty-two subjects are described, but there are only cuts of two, the 329 Queen and the Duchess. In 1490 an edition appeared with the following title: “Chorea ab eximio Macabro versibus Alemanicis edita, et à Petro Desrey emendata. Parisiis, per magistrum Guidonem Mercatorem [Guy Marchand] pro Godefrido de Marnef.” In the same year Marchand printed another edition of “La nouvelle Danse Macabre des Hommes;” and in the year following there appeared from his press a second edition of “La Danse Macabre des Femmes,” with cuts of all the characters and other additions. A Dance of Death, according to Von der Hagen, in his Deutsche Poesie, p. 459, was printed at Leipsic in 1496; and in 1499 a “Grande Danse Macabre des Hommes et Femmes” was printed in folio at Lyons. The latter is supposed to be the earliest that contains cuts of both men and women. About 1500, Ant. Verard printed an edition, in folio, of the Danse Macabre at Paris; and in various years between 1500 and 1530 a work with the same title and similar cuts was printed at Paris, Troyes, Rouen, Lyons, and Geneva. Besides those works, characters from the Dance of Death were frequently introduced as incidental illustrations in books of devotion, more especially in those usually denominated Horæ or Hours of the Virgin, and printed in France.VI.6

The celebrated “Dance of Death,” the cuts of which have been so generally ascribed to Hans Holbein as the engraver as well as designer, was first published at Lyons, in 1538. It is of small quarto size, and the title is as follows: “Les Simulachres & Historiées faces de la Mort, autant elegammēt pourtraictes, que artificiellement imaginées. A Lyon, Soubz l’escu de Coloigne. M.D.XXXVIII.” On the title-page is an emblematic wood-cut, very indifferently executed, representing three heads joined together, with a wreath above them; the middle one a full face, and those on each side in profile. Instead of shoulders, the heads, or busts, are provided with a pair of wings of peacock’s feathers; they 330 rest on a kind of pedestal, on which is also an open book inscribed with the maxim, “ΓΝΩΘΙ ΣΕΑΥΤΟΝ.” A large serpent is seen confined by the middle in a hole which must be supposed to pass through the pedestal; and to it (the pedestal) are chained two globes,—one surmounted by a small cross, like the emblem of imperial authority, and the other having two wings. This emblematic cut, which is certainly not “l’escu de Coloigne,” is accompanied with the motto “Usus me Genuit.”VI.7 At the conclusion of the book is the imprint, within an ornamental wood-cut border: “EXCVDEBANT LVGDVNI MELCHIOR ET GASPAR TRECHSEL FRATRES. 1538.” The title is succeeded by a preface, of six pages, which is followed by seven pages more, descriptive of “diverses tables de Mort, non painctes, mais extraictes de l’escripture saincte, colorées par Docteurs Ecclesiastiques, et umbragées par Philosophes.” After those verbal sketches of Death come the cuts, one on each page; and they are succeeded by a series of descriptions of death and reflections on mortality, the general title to which, commencing at signature H, is, “Figures de la Mort moralement descriptes, & depeinctes selon l’authorité de l’scripture, & des sainctz Peres.”

By far the most important passage in the book, at least so far as relates to the designer or engraver of the cuts, occurs in the preface, which is written much in the style of a pedantic father-confessor to a nunnery who felt a pleasure in ornamenting his Christian discourses and exhortations with the flowers of Pagan eloquence. The preface is addressed, “A moult reverende Abbesse du religieux convent S. Pierre de Lyon, Madame Jehanne de Touszele, Salut dun vray Zele,”VI.8 and the passage above mentioned is to the following effect. “But to return to our figured representations of Death, we have greatly to regret the death of him who has imagined such elegant figures as are herein contained, as much excelling all those heretofore printed,VI.9 as the pictures of Apelles or of Zeuxis surpass those of modern times; for, his funereal histories, 331 with their gravely versified descriptions, excite such admiration in beholders, that the figures of Death appear to them most life-like, while those of the living are the very pictures of mortality. It therefore seems to me that Death, fearing that this excellent painter would paint him in a manner so lively, that he should be no longer feared as Death, and apprehensive that the artist would thus become immortal, determined to shorten his days, and thus prevent him finishing other subjects which he had already drawn. Among these is one of a waggoner, knocked down and crushed under his broken waggon, the wheels and horses of which appear so frightfully shattered and maimed that it is as fearful to see their overthrow as it is amusing to behold the liquorishness of a figure of Death, who is perceived roguishly sucking the wine out of a broken cask, by means of a reed. To such imperfect subjects, as to the inimitable heavenly bow named Iris,VI.10 no one has ventured to put the last hand, on account of the bold drawing, perspectives, and shadows contained in this inimitable chef-d’œuvre, there so gracefully delineated, that from it we may derive a pleasing sadness and a melancholy pleasure, as in a thing mournfully delightful.” The cut of the waggoner, described by the French euphuist, was, however, afterwards finished, and, with others, inserted in a subsequent edition of the work. It is figured in the present volume at page 344.

The number of cuts in the first edition, now under examination, is forty-one; above each is a text of Scripture, in Latin; and below are four verses in French—the “descriptions severement rithmées,” mentioned in the preface—containing some moral or reflection germane to the subject. A few sets of impressions of all those cuts, except one, appear to have been taken before the work appeared at Lyons. They have been printed by means of a press,—not taken by friction in the manner in which wood engravers usually take their proofs,—and at the top of each cut is the name in the German language, but in Italic type. “Why those German names,” says Hegner, “in a work which, so far as we know, was first published at Lyons? They appear to confirm the opinion of the cuts having been actually engraved at Basle; and the descriptions correspond with the dialect of that city.” The late Mr. Ottley had impressions of forty of those original cuts, and six of those which were inserted in a later edition. In his Inquiry into the Origin and Early History of Engraving, Mr. Ottley, speaking of the Dance of Death, says: “It is certain that the cuts had been previously printed at Basle; and, indeed, some writers assert that the work was published in that city, with texts of Scripture, in the German language, above the cuts, and verses, in the 332 same language, underneath, as early as 1530; although, hitherto, I have been unable to meet with or hear of any person who had seen a copy of such an edition.” In a note upon this passage, Jansen, the compiler of an Essay on the Origin of Engraving, and the anonymous author of a work entitled Notices sur les Graveurs, Besançon, 1807, are cited as mentioning such an edition. To give every one his due, however, and to show the original authority for the existence of such an edition, I beg here to give an extract from Papillon, who never felt any difficulty in supposing a date, and whose conjectures such writers as Jansen have felt as little hesitation in converting into certainties. The substance of Papillon’s observations on this point is as follows: “But to return to Holbein’s Dance of Death, which is unquestionably a master-piece of wood engraving. There are several editions; the first of which, so far as may be judged, ought to be about 1530, as has been already said,VI.11 and was printed at Basle or Zurich, with a title to each cut, and, I believe, verses underneath, all in the German language.” What Papillon puts forth as a matter of conjecture and opinion, Von Murr, Jansen, and the author of the Notices sur les Graveurs, promulgate as facts, and Mr. Ottley refers to the two latter writers as if he were well inclined to give credit to their assertions.

From the following passage it would appear that Mr. Ottley had also been willing to believe that those impressions might have been accompanied with explanatory verses and texts of Scripture. “I have only to add, upon the subject of this celebrated work, that I am myself the fortunate possessor of forty pieces, (the complete series of the first edition, excepting one,) which are printed with the greatest clearness and brilliancy of effect, on one side of the paper only; each cut having over it its title, printed in the German language with moveable type. It is possible that they may originally have had verses underneath, and texts of Scripture above, in addition to the titles just mentioned: but as the margins are clipped on the sides and at bottom, it is now impossible to ascertain the fact.”VI.12

Had the forty impressions in question been accompanied with verses and texts of Scripture, they certainly might be considered as having 333 belonged to an earlier edition of the work than that of 1538, and for the existence of which Mr. Ottley has referred to the testimony of Jansen and the editor of the Notices sur les Graveurs, printed at Besançon. There is, however, a set of those cuts preserved in the public library at Basle, which seems clearly to prove that they had only been taken as specimens without any further accompaniment than the titles. They are printed on four folio leaves, on only one side of the paper, and there are ten cuts on each page; the title, in the German language, and in Italic type, like Mr. Ottley’s, is printed above each; and the same cut—that of the astrologer—is also wanting. From these circumstances there can scarcely be a doubt that the set formerly belonging to Mr. OttleyVI.13 had been printed in the same manner, and that each impression had subsequently been cut out, perhaps for the purpose of mounting them singly. The following are the titles given to those cuts, and to each is subjoined a literal translation. They are numbered as they follow each other in Les Simulachres et Historiees Faces de la Mort, 1538, which perhaps may not be incorrectly expressed by the English title, “Pictorial and Historical Portraits of Death.”

1. Die schöpfung aller ding—The creation of all things.

2. Adam Eua im Paradyſs—Adam and Eve in Paradise.

3. Vertribung Ade Eue—The driving out of Adam and Eve.

4. Adam baugt die erden—Adam cultivates the earth.

5. Gebeyn aller menschen—Skeletons of all men.

6. Der Papst—The Pope.

7. Der Keyser—The Emperor.

8. Der Künig—The King.

9. Der Cardinal—The Cardinal.

10. Die Keyserinn.—The Empress.

11. Die Küniginn—The Queen.

12. Der Bischoff—The Bishop.

13. Der Hertzog—The Duke.

14. Der Apt—The Abbot.

15. Die Aptissinn—The Abbess.

16. Der Edelman—The Nobleman.

17. Der Thümherr—The Canon.

18. Der Richter—The Judge.

19. Der Fürspräch—The Advocate.

20. Der Rahtsherr—The Magistrate.

21. Der Predicant—The Preaching Friar.

22. Der Pfarrherr—The Parish-priest.

23. Der Münch—The Monk.

24. Die Nunne—The Nun.

25. Dass Altweyb—The Old Woman.

33426. Der Artzet—The Doctor.

27. (Wanting in the specimens.) The Astrologer.

28. Der Rychman—The Rich Man.

29. Der Kauffman—The Merchant.

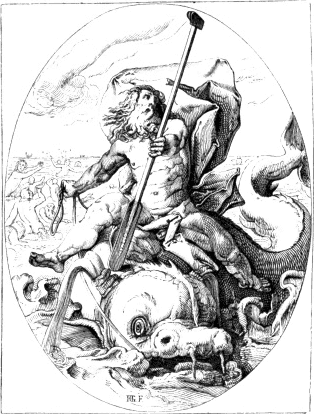

30. Der Schiffman—The Sailor.

31. Der Ritter—The Knight.

32. Der Graff—The Count.

33. Der Alt man—The Old Man.

34. Die Greffinn—The Countess.

35. Die Edelfraw—The Lady.

36. Die Hertzoginn—The Duchess.

37. Der Krämer—The Pedlar.

38. Der Ackerman—The Farmer.

39. Das Jung Kint—The Young Child.

40. Das Jüngst Gericht—The Last Judgment.

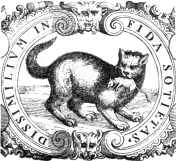

41. Die Wapen des Thots—Death’s coat-of-arms.

In 1542 a second edition of the Dance of Death, with the same cuts as the first, was published at Lyons, “Soubz l’escu de Coloigne,” by John and Francis Frellon, who appear to have succeeded to the business of the brothers Trechsel,—if, indeed, the latter were not merely the printers of the first edition. In a third edition, with the title Imagines Mortis, 1545, the verses underneath each cut are in Latin.VI.14 A cut of a lame beggar, which has no relation to the Dance of Death, is introduced as a tail-piece to one of the discourses on death—Cypriani Sermo de Mortalitate—at the end of the volume; but it is neither designed nor executed in the same style as the others.

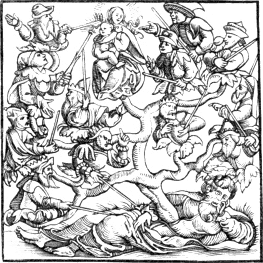

In a fourth edition, with the title “Imagines Mortis,”VI.15 1547, eleven additional cuts are introduced; namely: 1. Death fighting with a soldier in Swiss costume; 2. Gamblers, with a figure of Death, and another of the Devil; 3. Drunkards, with a figure of Death; 4. The Fool, with a figure of Death playing on the bagpipes; 5. The Robber seized by Death; 6. The Blind Man and Death; 7. The Waggoner and Death; 8. Children, one of whom is borne on the shoulders of the others as a conqueror triumphing; 9. A child with a shield and dart; 10. Three children; one riding on an arrow, another on a bow, as on a hobby-horse, the third carrying a hare over his shoulder, suspended from a hunting pole; 11. Children as Bacchanalians. The last four subjects have no relation to a Dance of Death, but have evidently been introduced merely to increase the number of the cuts; they are, however, beautifully designed and well engraved. This edition contains twelve more cuts, reckoning the tail-piece of the Lame Beggar, than the first. Another edition, forming the fifth, was also published in 1547 under the title of “Les Images de la 335 Mort,” with French verses, as in the edition of 1538. The number of cuts is the same as in the edition of 1547 with Latin verses, and the title “Imagines Mortis,” or “Icones Mortis.”

In 1549, a sixth edition, with the same number of cuts as the last, was published, under the title of “Simolachri, Historie, e Figure de la Morte,” with the letter-press in Italian, with the exception of the texts of Scripture, which were in Latin, as in the others. In the preface, John Frellon—whose name appears alone in the edition of 1547, and in those of subsequent years—complains of a piracy of the book, which was printed at Venice in 1545, with fac-similes of the cuts of the first edition. “Frellon, by way of revenge,” says Mr. Douce, “and to save the trouble of making a new translation of the articles that compose the volume, made use of that of his Italian competitor.”VI.16 A seventh edition, with the title “Icones Mortis,” and containing fifty-three cuts, appeared, without any printer’s name, in 1554.

In an eighth edition, 1562, with the title “Les Images de la Mort, auxquelles sont adjoustees dix-sept figures,” five additional cuts are introduced, thus making seventeen more than are contained in the first. The total number of cuts in the edition of 1562 is fifty-eight; and that of the Lame Beggar, which first appeared as a tail-piece in the edition of 1545, has now a place among the others in the body of the book. The subjects of the five new cuts are: 1. The Husband, with a figure of Death; 2. The Wife,—Death leading a young woman by the hand, preceded by a young man playing on a kind of guitar; 3. Children as part of a triumph, one of them as a warrior on horseback; 4. Three children; one with a trophy of armour, another carrying a vase and a shield, the third seated naked on the ground; 5. Children with musical instruments. The subjects of children are designed and executed in the same style as those first introduced in the edition of 1547. The last of those five new cuts does not appear in regular order with the other fifty-seven; but is given as a tail-piece at the end of a preface to a devotional tract—La Medicine de l’Ame—in the latter part of the book. Mr. Douce mentions another edition with the date 1574. He, however, observes in a note: “This edition is given on the authority of Peignot,VI.17 page 62, but has not been seen by the author of this work. In the year 1547 there were three editions, and it is not improbable that, by the transposition of the two last figures, one of these might have been intended.” As one of Mr. Douce’s three editions of 1547 differs only 336 from another of the same date by having “Icones” instead of “Imagines” in the title-page, he might as consistently have claimed a fourth for the same year on the ground of a probable transposition of 74 for 47. All the authentic editions of the “Dance of Death,” previously noticed, were published at Lyons. The first, as has been already observed, was in small quarto; the others are described by Mr. Douce as being in duodecimo. In a Dutch Dance of Death, intitled “De Doodt vermaskert met swerelts ydelheit,” duodecimo, Antwerp, 1654, fourteen of the cuts, according to Mr. Douce, were from the original blocks which had been used in the Lyons editions.

It seems probable that the earliest copies of the cuts in “Les

Simulachres et Historiées Faces de la Mort,” or Dance of Death, as the

work is more frequently called, appeared in a small folio, intitled

“Todtentantz,” printed at Augsburg in 1544, by “Jobst Denecker,

Formschneyder.” As I have never seen a copy of this edition,

I take the liberty of extracting the following notice of it from

Mr. Douce: “This edition is not only valuable from its extreme rarity,

but for the very accurate and spirited manner in which the fine original

cuts are copied. It contains all the subjects that were then published,

but not arranged as those had been. It has the addition of one singular

print, intitled, ‘Der Eebrecher,’ i. e. the Adulterer,

representing a man discovering the adulterer in bed with his wife, and

plunging his sword through both of them, Death guiding his hands. On the

opposite page to each engraving there is a dialogue between Death and

the party, and at bottom a Latin hexameter. The subject of the Pleader

has the unknown mark ![]() and on that of the Duchess in

bed, there is the date 1542.”VI.18 Mr. Douce is of opinion that the

“Jobst Denecker, Formschneyder,” who appears as the printer, was

the same person as Jobst or Jost de Negker, the wood engraver whose name

is at the back of one of the cuts of the Triumphal Procession of

Maximilian.—The next copy of the work is that intitled

“Simolachri, Historie, e Figure de la Morte,” Venice, 1545, the

piracy complained of by Frellon in his Italian edition of 1549. It

contains forty-one cuts, as in the first Lyons edition of 1538. There is

no variation in the figures; but the expression of the faces is

frequently lost, and the general execution of the whole is greatly

inferior to that of the originals. Another edition, in Latin, was

published in 1546; and Mr. Douce says that there are impressions of the

cuts on single sheets, at the bottom of one of which is the date

1568.—In 1555, an edition with the title “Imagines Mortis,” with

fifty-three cuts, similar to those in the Lyons edition of 1547, was

published at Cologne by the heirs of Arnold Birkman, Cologne, 1555; and

there are four other editions of the same work, respectively dated 1557,

1566, 1567, and 1572. Alterations are

337

made in some of those cuts; in five of them the mark

and on that of the Duchess in

bed, there is the date 1542.”VI.18 Mr. Douce is of opinion that the

“Jobst Denecker, Formschneyder,” who appears as the printer, was

the same person as Jobst or Jost de Negker, the wood engraver whose name

is at the back of one of the cuts of the Triumphal Procession of

Maximilian.—The next copy of the work is that intitled

“Simolachri, Historie, e Figure de la Morte,” Venice, 1545, the

piracy complained of by Frellon in his Italian edition of 1549. It

contains forty-one cuts, as in the first Lyons edition of 1538. There is

no variation in the figures; but the expression of the faces is

frequently lost, and the general execution of the whole is greatly

inferior to that of the originals. Another edition, in Latin, was

published in 1546; and Mr. Douce says that there are impressions of the

cuts on single sheets, at the bottom of one of which is the date

1568.—In 1555, an edition with the title “Imagines Mortis,” with

fifty-three cuts, similar to those in the Lyons edition of 1547, was

published at Cologne by the heirs of Arnold Birkman, Cologne, 1555; and

there are four other editions of the same work, respectively dated 1557,

1566, 1567, and 1572. Alterations are

337

made in some of those cuts; in five of them the mark ![]() is introduced; and in the cut of the Duchess the mark

is introduced; and in the cut of the Duchess the mark ![]() , seen on the bed-frame in the original, is omitted. All the

alterations are for the worse; some of the figures seem like caricatures

of the originals; and the cuts generally are, in point of execution,

very inferior to those in the Lyons editions. The name of the artist to

whom the mark

, seen on the bed-frame in the original, is omitted. All the

alterations are for the worse; some of the figures seem like caricatures

of the originals; and the cuts generally are, in point of execution,

very inferior to those in the Lyons editions. The name of the artist to

whom the mark ![]() belongs is unknown. In the preface to

the Emblems of Mortality, page xx, the writer says it is “that of Silvius Antonianus, an artist of considerable

merit.” This, however, is merely one of the blunders of Papillon, who,

according to Mr. Douce, has converted the owner of this mark into a

cardinal. Papillon, it would seem, had observed it on the cuts of an

edition of Faerno’s Fables—printed at Antwerp, 1567, and dedicated

to Cardinal Borromeo by Silvio Antoniano, professor of Belles Lettres at

Rome, afterwards a cardinal himself—and without hesitation he

concluded that the editor was the engraver.VI.19 The last of the

editions published in the sixteenth century with wood-cuts copied from

the Lyons work, appeared at Wittemberg in 1590.

belongs is unknown. In the preface to

the Emblems of Mortality, page xx, the writer says it is “that of Silvius Antonianus, an artist of considerable

merit.” This, however, is merely one of the blunders of Papillon, who,

according to Mr. Douce, has converted the owner of this mark into a

cardinal. Papillon, it would seem, had observed it on the cuts of an

edition of Faerno’s Fables—printed at Antwerp, 1567, and dedicated

to Cardinal Borromeo by Silvio Antoniano, professor of Belles Lettres at

Rome, afterwards a cardinal himself—and without hesitation he

concluded that the editor was the engraver.VI.19 The last of the

editions published in the sixteenth century with wood-cuts copied from

the Lyons work, appeared at Wittemberg in 1590.

Various editions of the Dance of Death, with copper-plate engravings generally copied from the work published at Lyons, are enumerated by Mr. Douce, but only one of them seems to require notice here. Between 1647 and 1651 Hollar etched thirty subjects from the Dance of Death, introducing occasionally a few alterations. From a careful examination of those etchings, I am inclined to think that most of them were copied not from the cuts in any of the Lyons editions, but from those in the edition published by the heirs of Birkman at Cologne. The original copper-plates of Hollar’s thirty etchings having come into the possession of Mr. James Edwards, formerly a bookseller in Pall-Mall, he published an edition in duodecimo, without date, but about 1794,VI.20 with preliminary observations on the Dance of Death, written by the late Mr. F. Douce. Those preliminary observations are the germ of Mr. Douce’s beautiful and more complete volume, published by W. Pickering in 1833 (and republished with additions by Mr. Bohn in 1858). As Petrarch’s amatory sonnets and poems have been called “a labour of Love,” with equal 338 propriety may Mr. Douce’s last work be intitled “a labour of Death.” Scarcely a cut or an engraving that contains even a death’s head and cross-bones appears to have escaped his notice. Incorporated is a Catalogue raisonné which contains an enumeration of all the tomb-stones in England and Wales that are ornamented with those standard “Emblems of Mortality,”—skull, thigh-bones in saltire, and hour-glass. In his last “Opus Magnum Mortis,” the notices of the several Dances of Death in various parts of Europe are very much enlarged, but he has not been able to adduce any further arguments or evidences beyond what appeared in his first essay, to show that the cuts in the original edition of the Dance of Death, published at Lyons, were not designed by Holbein. Throughout the work there are undeniable proofs of the diligence of the collector; but no evidences of a mind that could make them available to a useful end. He is at once sceptical and credulous; he denies that any poet of the name of Macaber ever lived; and yet he believes, on the sole authority of one T. Nieuhoff Picard, whose existence is as doubtful as Macaber’s, that Holbein painted a Dance of Death as large as life, in fresco, in the old palace at Whitehall.

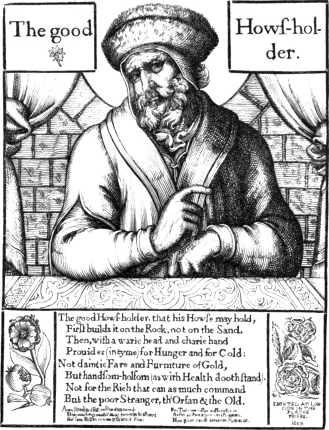

Having now given a list of all the authentic editions of the Dance of Death and of the principal copies of it, I shall next, before saying anything about the supposed designer or engraver, lay before the reader a few specimens of the original cuts. Mr. Douce observes, of the forty-nine cuts given in his Dance of Death, 1833, that “they may be very justly regarded as scarcely distinguishable from their fine originals.” Now, without any intention of depreciating these clever copies, I must pronounce them inferior to the originals, especially in the heads and hands. In this respect the wood-cuts of the first Lyons edition of the Dance of Death are unrivalled by any other productions of the art of wood engraving, either in past or present times. In the present day, when mere delicacy of cutting in the modern French taste is often mistaken for good engraving, there are doubtless many admirers of the art who fancy that there would be no difficulty in finding a wood engraver who might be fully competent to accurately copy the originals in the first edition of the Dance of Death. The experiment, however, would probably convince the undertaker of such a task, whoever he might be, that he had in this instance over-rated his abilities. Let the heads in the Lyons cuts, and those of any copies of them, old or recent, be examined with a magnifying glass, and the excellence of the former will appear still more decidedly than when viewed with the naked eye.

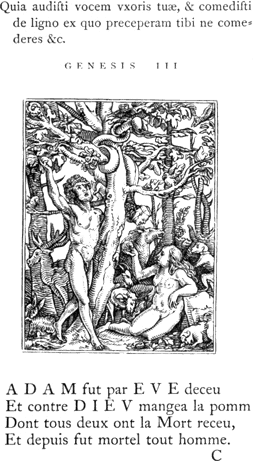

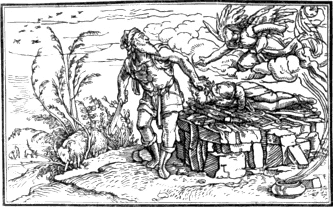

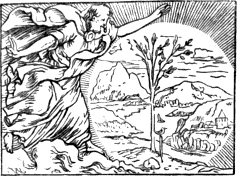

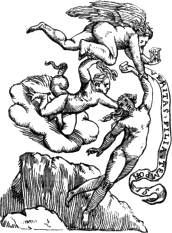

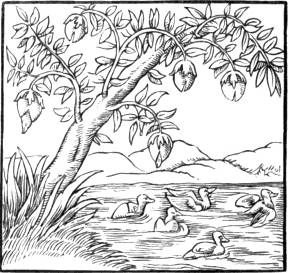

The following cut is a copy of the same size as the original, which is the second of the Dance of Death, of the edition of 1538. The subject is Adam and Eve eating of the forbidden fruit; and in the series of early impressions, formerly Mr. Ottley’s, but now in the Print Room of 339 the British Museum, it is intitled “Adam Eva im Paradyss”—Adam and Eve in Paradise. The serpent, as in many other old engravings, as well as in paintings, is represented with a human face. In order to convey an idea of the original page, this cut is accompanied with its explanatory text and verses printed in similar type.

In the two first cuts, which represent the Creation of Eve, and Adam taking the forbidden fruit, the figure of Death is not seen. In the third, Adam and Eve driven out of Paradise, Death, playing on a kind of lyre, is seen preceding them; and in the fourth, Adam cultivating the earth, Death is perceived assisting him in his labour. In the fifth, intitled Gebeyn aller menschen—Skeletons of all men—in the early impressions of the cuts, formerly belonging to Mr. Ottley, but now in the British Museum, all the figures are skeletons; one of them is seen beating a pair of kettle drums, while others are sounding trumpets, as if rejoicing 340 in the power which had been given to Death in consequence of the fall of man. The texts above this cut are, “Væ væ væ habitantibus in terra. Apocalypsis viii;” and “Cuncta in quibus spiraculum vitæ est, mortua sunt. Genesis vii.” In the sixth cut there are two figures of Death,—one grinning at the pope as he bestows the crown on a kneeling emperor, and the other, wearing a cardinal’s hat, as a witness of the ceremony. In the thirty-sixth cut, the Duchess, there are two figures of Death introduced, and there are also two in the thirty-seventh, the Pedlar; but in all the others of this edition, from the seventh to the thirty-ninth, inclusive, there is only a single figure of Death, and in every instance his action and expression are highly comic, most distinctly evincing that man’s destruction is his sport. In the fortieth cut there is no figure of Death; the Deity seated on a rainbow, with his feet resting on the globe, is seen pronouncing final judgment on the human race. The forty-first, and last cut of the original edition, represents Death’s coat-of-arms——Die wapen des Thots. On an escutcheon, which is rent in several places, is a death’s-head, with something like a large worm proceeding from the mouth; above the escutcheon, a barred helmet, seen in front like that of a sovereign prince, is probably intended to represent the power of Death; the crest is a pair of fleshless arms holding something like a large stone immediately above an hour-glass; on the dexter side of the escutcheon stands a gentleman, who seems to be calling the attention of the spectator to this memento of Death, and on the opposite side is a lady; in the distance are Alpine mountains, the top of the highest partly shaded by a cloud. The appropriate text is, “Memorare novissima, 341 et in æternum non peccabis. Eccle. vii;” and the following are the verses underneath:

“Si tu veulx vivre sans peché

Voy ceste imaige a tous propos,

Et point ne seras empesché

Quand tu t’en iras en repos.”

The total number of cuts of the first edition in which Death is seen attending on men and women of all ranks and conditions, mocking them, seizing them, slaying them, or merrily leading them to their end, is thirty-seven.

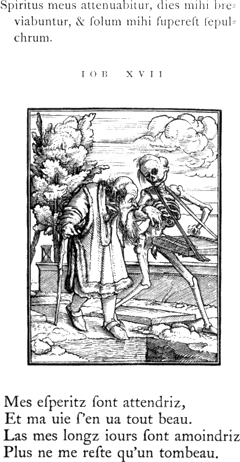

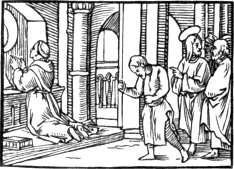

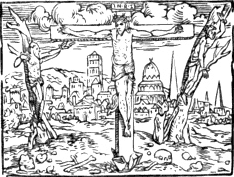

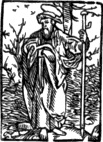

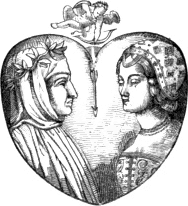

The above cut is a copy of the thirty-third, the Old Man—Der Alt man—whom Death leads in confiding imbecility to the grave, while he 342 pretends to support him and to amuse him with the music of a dulcimer. The text and verses are given as they stand in the original.

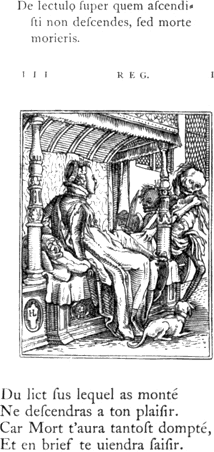

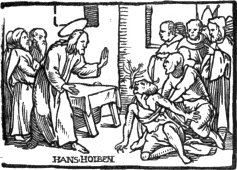

The following cut is a copy of the thirty-sixth, the

Duchess—Die Hertzoginn. In this cut, as has been previously

observed, there are two figures of Death; one rouses her from the

bed—where she appears to have been indulging in an afternoon

nap—by pulling off the coverlet, while the other treats her to a

tune on the violin. On the frame of the bed, or couch, to the left, near

the bottom of the cut, is seen the mark ![]() , which

has not a little increased the difficulty of arriving at any clear and

unquestionable conclusion with respect to the designer or engraver of

those cuts. The text and the verses are given literally, as in the two

preceding specimens.

, which

has not a little increased the difficulty of arriving at any clear and

unquestionable conclusion with respect to the designer or engraver of

those cuts. The text and the verses are given literally, as in the two

preceding specimens.

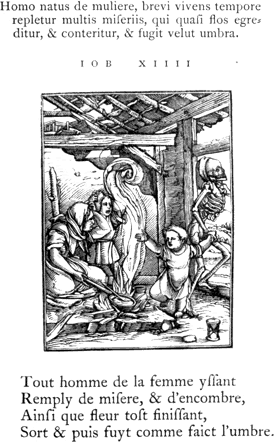

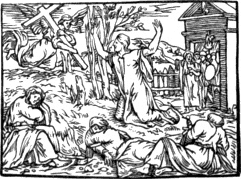

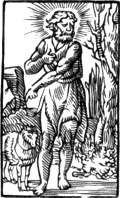

The following cut, the Child—Das Iung Kint—is a copy of the thirty-ninth, and the last but two in the original edition. Death having been represented in the preceding cuts as beguiling men and women in court and council-chamber, in bed-room and hall, in street and field, by sea and by land, is here represented as visiting the dilapidated cottage of the poor, and, while the mother is engaged in cooking, seizing her youngest child.

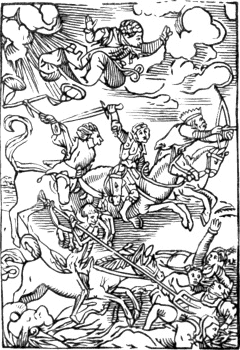

The cut of the Waggon overturned, from which the following is copied, first appeared with ten others in the edition of 1547. From an inspection of this cut, which most probably is that mentioned as being left unfinished, in the prefatory address to Madame Jehanne de Touszele in the first edition, 1538, it will be perceived that the description which is there given of it is not correct, and hence arises 344 a doubt if the writer had actually seen it. He describes the driver as knocked down, and lying bruised under his broken waggon, and he says that the figure of Death is perceived roguishly sucking the wine out of a broken cask by means of a reed.VI.21 In the cut itself, however, the waggoner is seen standing, wringing his hands as if in despair on account of the accident, and a figure of Death,—for there are two in this cut,—instead of sucking the wine, appears to be engaged in undoing the rope or chain by which the cask is secured to the waggon. A second figure of Death is perceived carrying off one of the waggon-wheels. In this cut the subject is not so well 345 treated as in most of those in the edition of 1538; and it is also not so well engraved.—The text and verses annexed are from the edition of 1562.

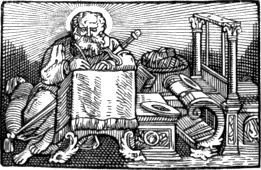

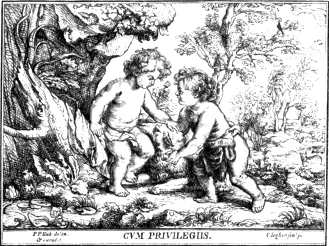

Of the eleven additional cuts inserted in the edition of 1547, there are four of children, which, as has already been observed in page 334, have not the slightest connexion with the Dance of Death. The following is a copy of one of them. The editor seems to have found no difficulty in providing the subject with a text; and it serves as a peg to hang a quatrain on as well as the others which contain personifications of Death.

In the edition of 1562 five more cuts are inserted; but two of them only—the Bridegroom and the Bride—have relation to the Dance of Death; the other three are of a similar character to the four cuts of children first inserted in the edition of 1547. All the seven cuts of 346 children have been evidently designed by the same person. They are well engraved, but not in so masterly a style as the forty-one cuts of the original edition. The following is a copy of one of the three which were inserted in the edition of 1562.

Having now given what, perhaps, may be considered a sufficiently ample account of the Lyons Dance of Death, it next appears necessary to make some enquiries respecting the designer of the cuts. Until the publication of Mr. Douce’s observations, prefixed to the edition of Hollar’s etchings from those cuts, by Edwards, about 1794, scarcely any writer who mentions them seems to entertain a doubt of their having been designed by Holbein; and Papillon, in his usual manner, claims him as a wood engraver, and unhesitatingly declares that not only the cuts of the Lyons Dance of Death, but all the other cuts which are generally supposed to have been of his designing, were engraved by himself. Mr. Douce’s arguments are almost entirely negative,—for he produces no satisfactory evidence to show that those cuts were certainly 347 designed by some other artist,—and they are chiefly founded on the passage in the first Lyons edition, where the writer speaks of the death of the person “qui nous en a icy imaginé si elegantes figures.”

The sum of Mr. Douce’s objections to Holbein being the designer of the cuts in question is as follows. “The singularity of this curious and interesting dedication is deserving of the utmost attention. It seems very strongly, if not decisively, to point out the edition to which it is prefixed, as the first; and what is of still more importance, to deprive Holbein of any claim to the invention of the work. It most certainly uses such terms of art as can scarcely be mistaken as conveying any other sense than that of originality of design. There cannot be words of plainer import than those which describe the painter, as he is expressly called, delineating the subjects and leaving several of them unfinished: and whoever the artist might have been, it clearly appears that he was not living in 1538. Now, it is well known that Holbein’s death did not take place before the year 1554, during the plague which ravaged London at that time. If then the expressions used in this dedication signify anything, it may surely be asked what becomes of any claim on the part of Holbein to the designs of the work in question, or does it not at least remain in a situation of doubt and difficulty?”VI.22 With respect to the true import of the passage referred to, my opinion is almost directly the reverse of that expressed by Mr. Douce.

What the writer of the address to Madame Jehanne de Touszele, in the Lyons edition of 1538, says respecting the unfinished cuts, taken all together, seems to relate more properly to the engraver than the designer; more especially when we find that a cut—that of the Waggoner,—expressly noticed by him as being then unfinished, was given with others of a similar character in a subsequent edition.

From the incorrect manner in which the cut of the Waggoner is described, I am very much inclined to think that the writer had neither seen the original nor the other subjects already traced—the “plusieurs aultres figures jà par luy trassées”—of whose “bold drawing, perspectives, and shadows,” he speaks in such terms of admiration. If the writer knew little of the process of wood engraving, he would be very likely to commit the mistake of supposing that the engraver was also the designer of the cuts. Though I consider it by no means unlikely that the engraver might have been dead before the publication of the first edition, yet I am very much inclined to believe that the passage in which the cuts are mentioned is purposely involved in obscurity: the writer, while he speaks of the deceased artist in terms of the highest commendation, at the same time carefully conceals his name. If the account in the preface be admitted as correct, it would 348 appear that the cuts were both designed and engraved by the same person, and that those already drawn on the blockVI.23 remained unfinished in consequence of his decease; for if he were not the engraver, what prevented the execution of the other subjects already traced, and of which the bold drawing, perspective, and shadows, all so gracefully delineated, are distinctly mentioned? The engraver, whoever he might be, was certainly not only the best of his age, but continues unsurpassed to the present day, and I am satisfied that such precision of line as is seen in the heads could only be acquired by great practice. The designs are so excellent in drawing and composition, and so admirably are the different characters represented,—with such spirit, humour, and appropriate expression,—that to have produced them would confer additional honour on even the greatest painters of that or any other period. Are we then to suppose that those excellencies of design and of engraving were combined in an obscure individual whose name is not to be found in the roll of fame, who lived comparatively unknown, and whose death is only incidentally noticed in an ambiguous preface written by a nameless pedant, and professedly addressed to an abbess whose very existence is questionable?VI.24 Such a supposition I conceive to be in the highest degree improbable; and, on the contrary, I am perfectly satisfied that the cuts in question were not designed and engraved by the same person. Furthermore, admitting the address to Madame Jehanne de Touszele to be written in good faith, I am firmly of opinion that the person whose death is there mentioned, was the engraver, and not the designer of the cuts of the first edition.

The mark ![]() in the cut of the Duchess, is certainly

not Holbein’s; and Mr. Douce says, “that it was intended to express the

name of the designer, cannot be supported by evidence of any kind.” That

it is not the mark of the designer, I agree with Mr. Douce, but my

conclusion is drawn from premises directly the reverse of his; for had I

not found evidence elsewhere to convince me that this mark can only be

that of the engraver, I should most certainly have concluded that

it was intended for the mark of the designer. In direct opposition to

what Mr. Douce here says, up to the time of the publication of the Lyons

349

Dance of Death, the mark on wood-cuts is most frequently that of the

designer, and whenever that of the engraver appears, it is as an

exception to the general custom. It is, in fact, upon the evidence of

the mark alone that the greater part of the wood-cut designs of Durer,

Cranach, Burgmair, Behaim, Baldung, Grün, and other old masters, are

respectively ascribed to them. The cuts of the Triumphal Procession of

Maximilian with Hans Burgmair’s mark in front, and the names of the

engravers written at the back of the blocks, may serve as an

illustration of the general practice, which is directly the reverse of

Mr. Douce’s opinion. If the weight of probability be not on the opposite

side, the mark in question ought certainly, according to the usual

practice of the period, to be considered as that of the designer.

in the cut of the Duchess, is certainly

not Holbein’s; and Mr. Douce says, “that it was intended to express the

name of the designer, cannot be supported by evidence of any kind.” That

it is not the mark of the designer, I agree with Mr. Douce, but my

conclusion is drawn from premises directly the reverse of his; for had I

not found evidence elsewhere to convince me that this mark can only be

that of the engraver, I should most certainly have concluded that

it was intended for the mark of the designer. In direct opposition to

what Mr. Douce here says, up to the time of the publication of the Lyons

349

Dance of Death, the mark on wood-cuts is most frequently that of the

designer, and whenever that of the engraver appears, it is as an

exception to the general custom. It is, in fact, upon the evidence of

the mark alone that the greater part of the wood-cut designs of Durer,

Cranach, Burgmair, Behaim, Baldung, Grün, and other old masters, are

respectively ascribed to them. The cuts of the Triumphal Procession of

Maximilian with Hans Burgmair’s mark in front, and the names of the

engravers written at the back of the blocks, may serve as an

illustration of the general practice, which is directly the reverse of

Mr. Douce’s opinion. If the weight of probability be not on the opposite

side, the mark in question ought certainly, according to the usual

practice of the period, to be considered as that of the designer.

In a subsequent page of the same chapter, Mr. Douce most

inconsistently says, “There is an unfortunate ambiguity connected with

the marks that are found on ancient engravings on wood, and it has been

a very great error on the part of all the writers who treat on

such engravings, in referring the marks that accompany them to the

block-cutters, or as the Germans properly denominate them the

formschneiders, whilst, perhaps, the greatest part of them really

belong to the designers.” He commits in the early part of the chapter

the very error which he ascribes to others. According to his own

principles, as expressed in the last extract, he was bound to allow the

mark ![]() to be that of the designer until he could show

on probable grounds that it was not. But though Mr. Douce might deny

that Holbein were the designer of those cuts, it seems that he durst not

venture to follow up the line of his argument, and declare that Hans

Lutzelburger was the designer, which he certainly might have done

with at least as much reason as has led him to decide that Holbein

was not. But he prudently abstained from venturing on such an

affirmation, the improbability of which, notwithstanding the mark, might

have led his readers to inquire, how it happened that so talented an

artist should have remained so long undiscovered, and that even his

contemporaries should not have known him as the designer of those

subjects.

to be that of the designer until he could show

on probable grounds that it was not. But though Mr. Douce might deny

that Holbein were the designer of those cuts, it seems that he durst not

venture to follow up the line of his argument, and declare that Hans

Lutzelburger was the designer, which he certainly might have done

with at least as much reason as has led him to decide that Holbein

was not. But he prudently abstained from venturing on such an

affirmation, the improbability of which, notwithstanding the mark, might

have led his readers to inquire, how it happened that so talented an

artist should have remained so long undiscovered, and that even his

contemporaries should not have known him as the designer of those

subjects.

Though I am satisfied that the mark ![]() is that

of the engraver of the cuts in the first edition of the Lyons

Dance of Death, I by no means pretend to account for its appearing

alone—thus forming an exception to the general rule—without

the mark of the designer, and without any mention of his name either in

the title or preface to the book. We have no knowledge of the connexion

in the way of business between the working wood engravers and the

designers of that period; but there seems reason to believe that the

former sometimes got drawings made at their own expense and risk, and,

when engraved, either published them on their own account, or disposed

of them to booksellers and printers. It is

350

also to be observed that about the time of the publication of the first

Lyons edition of the Dance of Death, or a few years before, wood

engravers began to occasionally introduce their name or mark into the

cut, in addition to that of the designer. A cut, in a German

translation of Cicero de Officiis, Frankfort, 1538, contains two marks;

one of them being that of Hans Sebald Behaim, and the other, the letters

H. W., which I take to be that of the engraver. At a later period

this practice became more frequent, and a considerable number of

wood-cuts executed between 1540 and 1580 contain two marks; one of the

designer, and the other of the engraver: in wood-cuts designed by Virgil

Solis in particular, double marks are of frequent occurrence. As it

seems evident that the publishers of the Lyons Dance of Death were

desirous of concealing the name of the designer, and as it appears

likely that they had purchased the cuts ready engraved from a Swiss or a

German,—for the designs are certainly not French,—it surely

cannot be surprising that he should wish to affix his mark to those most

admirable specimens of art. Moreover, if those cuts were not executed

under the personal superintendence of the designer, but when he was

chiefly resident in a distant country, the engraver would thus have the

uncontrolled liberty of inserting his own mark; and more especially, if

those cuts were a private speculation of his own, and not executed for a

publisher who had employed an artist to make the designs. Another

reason, perhaps equally us good as any of the foregoing, might be

suggested; as those cuts are decidedly the best executed of any of that

period, the designer—even if he had opportunities of seeing the

proofs—might have permitted the mark of the engraver to appear on

one of them, in approbation of his talent.

is that

of the engraver of the cuts in the first edition of the Lyons

Dance of Death, I by no means pretend to account for its appearing

alone—thus forming an exception to the general rule—without

the mark of the designer, and without any mention of his name either in

the title or preface to the book. We have no knowledge of the connexion

in the way of business between the working wood engravers and the

designers of that period; but there seems reason to believe that the

former sometimes got drawings made at their own expense and risk, and,

when engraved, either published them on their own account, or disposed

of them to booksellers and printers. It is

350

also to be observed that about the time of the publication of the first

Lyons edition of the Dance of Death, or a few years before, wood

engravers began to occasionally introduce their name or mark into the

cut, in addition to that of the designer. A cut, in a German

translation of Cicero de Officiis, Frankfort, 1538, contains two marks;

one of them being that of Hans Sebald Behaim, and the other, the letters

H. W., which I take to be that of the engraver. At a later period

this practice became more frequent, and a considerable number of

wood-cuts executed between 1540 and 1580 contain two marks; one of the

designer, and the other of the engraver: in wood-cuts designed by Virgil

Solis in particular, double marks are of frequent occurrence. As it

seems evident that the publishers of the Lyons Dance of Death were

desirous of concealing the name of the designer, and as it appears

likely that they had purchased the cuts ready engraved from a Swiss or a

German,—for the designs are certainly not French,—it surely

cannot be surprising that he should wish to affix his mark to those most

admirable specimens of art. Moreover, if those cuts were not executed

under the personal superintendence of the designer, but when he was

chiefly resident in a distant country, the engraver would thus have the

uncontrolled liberty of inserting his own mark; and more especially, if

those cuts were a private speculation of his own, and not executed for a

publisher who had employed an artist to make the designs. Another

reason, perhaps equally us good as any of the foregoing, might be

suggested; as those cuts are decidedly the best executed of any of that

period, the designer—even if he had opportunities of seeing the

proofs—might have permitted the mark of the engraver to appear on

one of them, in approbation of his talent.

This mark, ![]() , was first assigned to a wood engraver

named Hans Lutzelburger, by M. Christian von Mechel,

a celebrated engraver of Basle, who in 1780 published forty-five

copper-plate engravings of a Dance of Death from drawings said to be by

Holbein, and which almost in every respect agree with the corresponding

cuts in the Lyons work, though of greater size.VI.25 M. Mechel’s

conjecture respecting the

351

engraver of those cuts appears to have been first published in the

sixteenth volume of Von Murr’s Journal; but though I am inclined to

think that he is correct, it has not been satisfactorily shown that Hans

Lutzelburger ever used the mark

, was first assigned to a wood engraver

named Hans Lutzelburger, by M. Christian von Mechel,

a celebrated engraver of Basle, who in 1780 published forty-five

copper-plate engravings of a Dance of Death from drawings said to be by

Holbein, and which almost in every respect agree with the corresponding

cuts in the Lyons work, though of greater size.VI.25 M. Mechel’s

conjecture respecting the

351

engraver of those cuts appears to have been first published in the

sixteenth volume of Von Murr’s Journal; but though I am inclined to

think that he is correct, it has not been satisfactorily shown that Hans

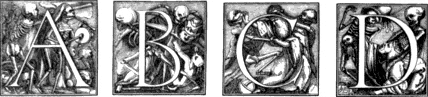

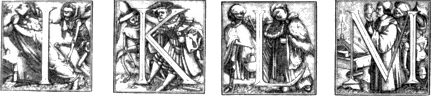

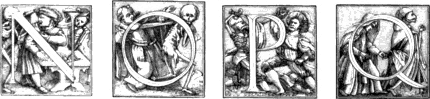

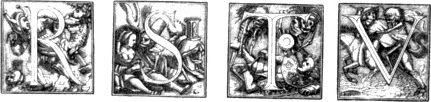

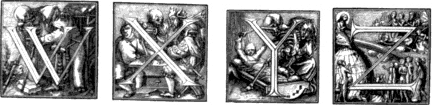

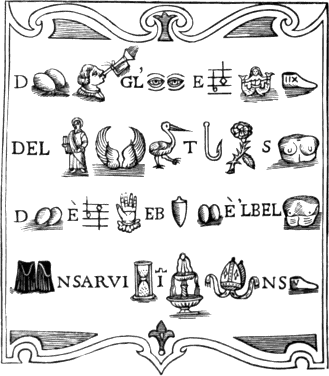

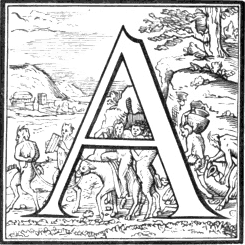

Lutzelburger ever used the mark ![]() . He,

however, lived at that period, and it is almost certain that he executed

an alphabet of small initial letters representing a Dance of Death,

which appear to have been first used at Basle by the printers Bebelius

and Cratander about 1530. We give (on the following page) the

entire series. He is also supposed to have engraved two other alphabets

of ornamental initial letters, one representing a dance of peasants,

“intermixed,” says Mr. Douce, “with other subjects, some of which are

not of the most delicate nature;” the other representing groups of

children in various playful attitudes. All those three alphabets are

generally described by German and Swiss writers on art as having been

designed by Holbein; and few impartial persons I conceive can have much

doubt on the subject, if almost perfect identity between most of the

figures and those in his known productions be allowed to have any

weight.

. He,

however, lived at that period, and it is almost certain that he executed

an alphabet of small initial letters representing a Dance of Death,

which appear to have been first used at Basle by the printers Bebelius

and Cratander about 1530. We give (on the following page) the

entire series. He is also supposed to have engraved two other alphabets

of ornamental initial letters, one representing a dance of peasants,

“intermixed,” says Mr. Douce, “with other subjects, some of which are

not of the most delicate nature;” the other representing groups of

children in various playful attitudes. All those three alphabets are

generally described by German and Swiss writers on art as having been

designed by Holbein; and few impartial persons I conceive can have much

doubt on the subject, if almost perfect identity between most of the

figures and those in his known productions be allowed to have any

weight.

There is a set of proofs of the alphabet of the Dance of Death,

printed on one sheet, preserved in the Public Library at Basle, and

underneath is printed in moveable letters the name HAnns Lützelburger formschnider, genannt

Franck,—that is, “Hanns Lutzelburger, wood engraver, named

Franck.” The first H is an ornamented Roman capital; the other letters

of the name are in the German character. The size of the cuts in this

alphabet of the Dance of Death is one inch by seven-eighths. The reason

for supposing that Hans Lutzelburger was the engraver of the cuts in the

first edition of the Lyons Dance of Death are: 1. The similarity of

style between the latter and those of the Basle alphabet of the same

subject; and 2. The correspondence of the mark in the cut of the

Duchess with the initial letters of the name H[ans] L[utzelburger], and

the fact of his being a wood engraver of that period. Mr. Douce, in the

seventh chapter of his work, professes to

353

examine the “claim of Hans Lutzelburger as to the design or execution of

the Lyons engravings of the Dance of Death,” but his investigations seem

very unsatisfactory; and his chapter is one of those “in which,” as

Fielding says, “nothing is concluded.” He gives no opinion as to whether

Lutzelburger was the designer of the Lyons cuts or not, though this is

one of the professed topics of his investigation; and even his opinion,

for the time being, as to the engraver, only appears in the heading of

the following chapter, where it is thus announced: “List of several

editions of the Lyons work on the Dance of Death, with the mark of

Lutzenburger.”VI.26 His mind, however, does not appear to have been

finally made up on this point; for in a subsequent page, 215, speaking

of the mark ![]() in the cut of the Duchess, which he had

previously mentioned as that of Hans Lutzelburger, he says, “but to

whomsoever this mark may turn out to belong, certain it is that

Holbein never made use of it.” His only unalterable decision appears to

be that Holbein did not design the cuts of the Lyons Dance of Death, and

in support of it he puts forth sundry arguments which are at once absurd

and inconsistent; rejects unquestionable evidence which makes for the

contrary opinion; and admits the most improbable that seems to favour

his own.

in the cut of the Duchess, which he had

previously mentioned as that of Hans Lutzelburger, he says, “but to

whomsoever this mark may turn out to belong, certain it is that

Holbein never made use of it.” His only unalterable decision appears to

be that Holbein did not design the cuts of the Lyons Dance of Death, and

in support of it he puts forth sundry arguments which are at once absurd

and inconsistent; rejects unquestionable evidence which makes for the

contrary opinion; and admits the most improbable that seems to favour

his own.

Mr. Douce, in his seventh chapter, also gives a list of cuts, which

he says were executed by Hans Lutzelburger; but out of the seven single

cuts and three alphabets which he enumerates, I am inclined to

think that Lutzelburger’s name is only to be found attached to one

single cut and to one alphabet,—the latter being that of the

initial letters representing a Dance of Death. The single cut to which I

allude—and which, I believe, is the only one of the kind that

has his name underneath it,—represents a combat in a wood between

some naked men and a body of peasants. Within the cut, to the left, is

the mark, probably of the designer, on a reversed tablet, ![]() thus; and underneath is the following inscription, from a

separate block: Hanns . Leuczellburger .

Furmschnider × 1.5.2.2. An impression of this cut is preserved in

the Public Library at Basle; and an alphabet of Roman capitals, engraved

on wood, is printed on the same folio, below Lutzelburger’s name. In not

one of the other single cuts does this engraver’s name occur, nor in

fact any mark that can be fairly ascribed to him. The seventh cut,

described by Mr. Douce,—a copy of Albert Durer’s Decollation of

John the Baptist,—is ascribed to Lutzelburger on the authority of

Zani. According to this writer,—for I have not seen the cut myself

any more than Mr. Douce,—it has “the mark H. L. reversed,”

which perhaps may prove to be L. H. “In the index of names,” says

Mr. Douce, “he (Zani) finds his name thus written, Hans

354

Lutzelburger Formschnider genant

(chiamato) Franck, and calls him the

true prince of engravers on wood.” In what index Zani found the reversed

mark thus expounded does not appear; I, however, am decidedly of opinion

that there is no wood-cut in existence with the mark H. L. which

can be ascribed with anything like certainty to Lutzelburger; and his

name is only to be found at length under the cut of the Fight

above mentioned, and printed in moveable characters on the sheet

containing the proofs of the alphabet of the Dance of Death.VI.27 The

title of “true prince of engravers on wood,” given by Zani to

Lutzelburger, can only be admitted on the supposition of his being the

engraver of the cuts in the first edition of the Lyons Dance of Death;

but it yet remains to be proved that he ever used the mark

thus; and underneath is the following inscription, from a

separate block: Hanns . Leuczellburger .

Furmschnider × 1.5.2.2. An impression of this cut is preserved in

the Public Library at Basle; and an alphabet of Roman capitals, engraved

on wood, is printed on the same folio, below Lutzelburger’s name. In not

one of the other single cuts does this engraver’s name occur, nor in

fact any mark that can be fairly ascribed to him. The seventh cut,

described by Mr. Douce,—a copy of Albert Durer’s Decollation of

John the Baptist,—is ascribed to Lutzelburger on the authority of

Zani. According to this writer,—for I have not seen the cut myself

any more than Mr. Douce,—it has “the mark H. L. reversed,”

which perhaps may prove to be L. H. “In the index of names,” says

Mr. Douce, “he (Zani) finds his name thus written, Hans

354

Lutzelburger Formschnider genant

(chiamato) Franck, and calls him the

true prince of engravers on wood.” In what index Zani found the reversed

mark thus expounded does not appear; I, however, am decidedly of opinion

that there is no wood-cut in existence with the mark H. L. which

can be ascribed with anything like certainty to Lutzelburger; and his

name is only to be found at length under the cut of the Fight

above mentioned, and printed in moveable characters on the sheet

containing the proofs of the alphabet of the Dance of Death.VI.27 The

title of “true prince of engravers on wood,” given by Zani to

Lutzelburger, can only be admitted on the supposition of his being the

engraver of the cuts in the first edition of the Lyons Dance of Death;

but it yet remains to be proved that he ever used the mark ![]() or the separate letters H. L. on any previous or subsequent

cut. Though, from his name appearing on the page containing the alphabet

of the Dance of Death, and from the correspondence of his initials with

the mark in the cut of the Duchess in the Lyons Dance of Death,

I am inclined to think that he was the engraver of the cuts in the

latter work, yet I have thought it necessary to enter thus fully into

the grounds of his pretensions to the execution of those, and other wood

engravings, in order that the reader may judge for himself.

or the separate letters H. L. on any previous or subsequent

cut. Though, from his name appearing on the page containing the alphabet

of the Dance of Death, and from the correspondence of his initials with

the mark in the cut of the Duchess in the Lyons Dance of Death,

I am inclined to think that he was the engraver of the cuts in the

latter work, yet I have thought it necessary to enter thus fully into

the grounds of his pretensions to the execution of those, and other wood

engravings, in order that the reader may judge for himself.

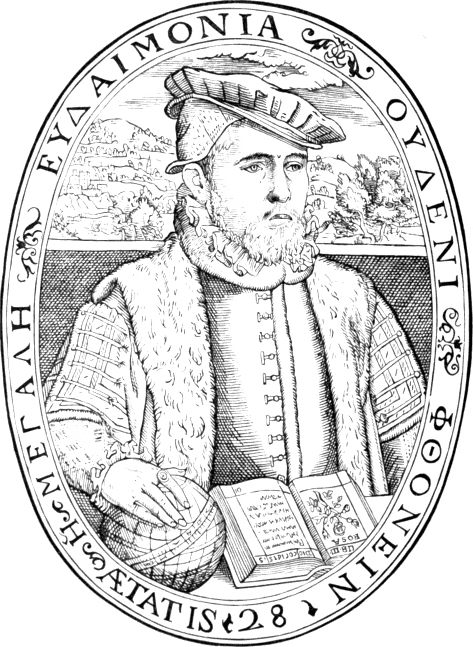

Hegner, in his Life of Holbein, treats the claims that have been advanced on behalf of Lutzelburger too lightly. He not only denies that he was the engraver of the cuts in the first edition of the Lyons work, but also that he executed the cuts of the alphabet of the Dance of Death, although his name with the addition of “wood engraver”—formschnider—be printed on the sheet of proofs. If we cannot admit the inscription in question as evidence of Lutzelburger being the engraver of this alphabet, we may with equal reason question if any wood engraver actually executed the cut or cuts under which his name only appears printed in type, or which may be ascribed to him in the title of a book. Mr. Douce, speaking of the three alphabets,—of peasants, boys, and a Dance of Death,—all of which he supposes to have been engraved by Lutzelburger, says that the proofs “may have been deposited by him in his native city,” meaning Basle. Hegner, however, says that there is no trace of him to be found either in registers of baptism or burger-lists of Basle. He further adds, though I by no means concur with him in this opinion, “It is indeed likely that, as a travelling dealer in works of art—who, according to the custom of that period, took up their temporary residence sometimes in one place, sometimes in another,—he had obtained possession of those blocks, [of the alphabet of Death’s Dance, and the Fight, with his name,] and that he sold impressions from them in 355 the way of trade.”VI.28 Mr. Douce says that it may admit of a doubt whether the alphabets ascribed to Lutzelburger were cut on metal or on wood. It may admit of a doubt, certainly, with one who knows very little of the practice of wood engraving, but none with a person who is accustomed to see cuts executed in a much more delicate style by wood engravers of very moderate abilities. To engrave them on wood, would be comparatively easy, so far as relates to the mere delicacy of the lines; but it would be a task of great difficulty to engrave them in relief in any metal which should be much harder than that of which types are composed. To suppose that they might have been executed in type-metal, on account of the delicacy of the lines, would involve a contradiction; for not only can finer lines be cut on box-wood than on type-metal, but also with much greater facility.

It perhaps may not be unnecessary to give here two instances of the

many vague and absurd conjectures which have been propounded respecting

the designer or the engraver of the cuts in the Lyons editions of the

Dance of Death. In a copy of this work of the edition 1545 now in the

British Museum, but formerly belonging to the Reverend C. M.

Cracherode, a portrait of a painter or engraver named Hans

Ladenspelder is inserted opposite to the cut of the Duchess, as if in

support of the conjecture that he might be the designer of those

cuts, merely from the circumstance of the initial letters of his name

corresponding with the mark ![]() . The

portrait is a small oval engraved on copper, with an ornamental border,

round which is the following inscription: “Imago Joannis Ladenspelder,

Essendiensis, Anno ætatis suæ xxviii. 1540.”VI.29 The mark

. The

portrait is a small oval engraved on copper, with an ornamental border,

round which is the following inscription: “Imago Joannis Ladenspelder,

Essendiensis, Anno ætatis suæ xxviii. 1540.”VI.29 The mark ![]() is perceived on this portrait, and underneath is written

the following MS. note, referring to the mark in the cut of the Duchess:

“

is perceived on this portrait, and underneath is written

the following MS. note, referring to the mark in the cut of the Duchess:

“![]() the mark of the designer of these designs of Death’s

Dance, not H. Holbein. By several persons that have seen Holbein’s

Death Dance at Basil, it is not like these, nor in the same manner.”

This note, so far as relates to the implied conjecture about

Ladenspelder, may be allowed to pass without remark for what it is

worth; but it seems necessary to remind the reader that the painting of

the Dance of Death at Basle, here evidently alluded to, was not

the work of Holbein, and to observe that this note is not in the

handwriting of Mr. Cracherode, but that it has apparently been written

by a former owner of the volume.

the mark of the designer of these designs of Death’s

Dance, not H. Holbein. By several persons that have seen Holbein’s

Death Dance at Basil, it is not like these, nor in the same manner.”

This note, so far as relates to the implied conjecture about

Ladenspelder, may be allowed to pass without remark for what it is

worth; but it seems necessary to remind the reader that the painting of

the Dance of Death at Basle, here evidently alluded to, was not